Upwardly Mobile: 'Connected World'

by Awl Sponsors

How will traffic become a thing of the past? How will the world change when every person on the planet has access to a cell phone? What if every thing on earth was connected to the internet? What will civilization 2.0 truly look like?

These are just a few of the questions AT&T; is looking at in their innovation series Upwardly Mobile. A bold look into what the next 20+ years has in store for us — speaking with everyone from a futurist architect to one of the creators of BitTorrent.

In Episode One, Connected World, we explore how the mobile network is transforming everything from our homes, to our cars, to the cities we live in. We call this the “internet of things,” a world of interconnected devices that not only controls our cars, thermostats and light switches, but automates them.

The Mobile Movement from AT&T; created an innovation series called Upwardly Mobile to document the ideas bringing the power of the mobile network to life, and the visionaries behind them. Watch the first episode of the Upwardly Mobile series here, and follow The Mobile Movement on YouTube.

Why Doesn't Your Phone Do More With What It Knows About You?

“Your phone has this incredible amount of information about you but doesn’t seem to do anything special with it.”

Festival Convened

“’When we started doing this, the longest a genetically-modified pig could survive in a bath of human blood was two hours and now that we are up to over eight days, it’s mind-blowing’” she said, in a wide-spanning conversation that drew an audience of hundreds at the South by Southwest conference.”

On The Breaking Of Shit

“If Yahoo was going to become a true digital news brand, it would have to go on a major innovation binge — it’d have to start ‘breaking shit,’ in other words. One senior news executive exulted that Yahoo News was in the most enviable position that any media company could be — it was a startup, he’d intone, that already had the largest readership on the web. This, too, was classic Yahoo corporate boilerplate: it sounded vaguely pulse-pounding when shouted above a PowerPoint stream, but on closer examination, it made no sense whatsoever. Precisely because it already commanded the largest readership, Yahoo couldn’t be a startup. Startups thrive on investor bets made on the promise of future profitability and, over the course of their initial runs, are case studies in capital destruction; far from ascending to Yahoo-scale market dominance, they’re expected to rapidly burn through their initial investment stakes en route to attracting more and bigger investors. For Yahoo to be a genuine startup, it would have to utterly fail at being Yahoo.”

— This dispatch from Awl pal Chris Lehmann on his time at Yahoo makes one shudder at the way the Internet used to be. Thank God everything’s different now.

My Ladyfriend Hates My Lady Friend

by The Concessionist

The Concessionist gives advice each weekend about the sordid choices of real life. Trouble? Write today.

Dear Concessionist,

I’m in a long distance relationship with my girlfriend and have been for about 1.5 years. It’s not always easy, it definitely takes effort, but it’s going great! We were friends before, and after a period of me chasing her we started dating. She’s probably my first serious girlfriend.

One problem is one of my good friends, who is a girl and lives just down the road in my city. We met on the first day of college and have been friends since, and to be clear, the relationship has always been platonic. Nothing remotely sexual/physical/romantic has ever happened between us, and it’s highly unlikely that something of that nature will ever develop. I see her like a sister, and I’m sure she views me the same way because during our friendship she’s always had boyfriends anyway.

The thing is, my girlfriend becomes a jealous, paranoid, insecure nutcase whenever I’m with my friend. The first time my girlfriend got really mad was because my friend and I watched a film together in her room, just us — which, to be fair, we’ve done millions of times before. It’s gotten to a point where I can’t even meet her for coffee without my girlfriend getting mad. And on another hand, objectively speaking, my girlfriend is way hotter than my friend is — all my guy friends are aghast that she could be so insecure.

What’s happened is that I’ve stopped seeing my friend so often, and when I do see her, I don’t tell my girlfriend. We don’t take pictures together and she can’t post anything related to me on social media. It would be less crazy if we were actually having an affair.

My friend feels bad that my girlfriend feels that way, and I feel bad that she feels bad. And as much as I care about my girlfriend’s feelings, she’s my good friend too and I do care about her. What do I do, Concessionist? What do I do?! Enlighten me!!

Signed,

Platonic Friend

Dear Platonic,

There’s a reason that some women get their hackles up about their boyfriends being friends with women. That’s because dudes are always cheating. Being cheated on is one of the 26 tolls that you pay when you date men. (The full list is pretty dreadful so I’ll spare you. Let’s just say that G is for Gaslighting and H is for HPV and I is for Infidelity. Yup, it’s going to make an AMAZING children’s book.)

I think you two should break up, because you called her a nutcase, and also, because she’s a nutcase. That’s a strike against each of you already in one short letter.

But if you would rather stay together, you’re going to have to talk about it until she is completely exhausted of the subject. The only way through this kind of thing is relentless talking. And even then she might still be like “Hey yeah I’m just not okay with this, why aren’t you listening to me? WHY ARE YOU SO STUPID? WHY DON’T YOU GET OUT AND LEAVE ME ALONE?” Etc.

To be fair to you, as far as we know, her fear of your best friend, no matter how well-founded in history, is still mean and small-hearted of her, and also kind of offensive.

Yes, historically, you’re the more error-prone and stupid of the two or so genders in your relationship. LET’S SIDEBAR: There’s a somewhat attractive school of thought here that would suggest that the two of you are closer to being of the same gender actually — when compared to single people, or queers, or gender outliers, or babies, or anyone that isn’t what y’all are. One point being: people that are this similar find pretty nuanced things to have conflict over! Like this argument you are having!

But your native male emotional disfigurement doesn’t mean that you’re not capable of being straightforward about fidelity. I believe in you. For now.

So you get to feel good because your girlfriend is close-minded and wrong — but not randomly so. Talk it out or breakup, yes.

But also the two of you should talk about what you want. Abandoning outside friends for a relationship is always a travesty. It’s also unhealthy.

Anything that brings a relationship closer to a closed and isolated dyad is bad. The conception of coupled lives as two people living unified against the world are both economically and socially unhealthy. They’re bad for aging, bad for spawning, and bad for people with any kind of health issues.

Even children, which of course I dislike intensely, are better than two people living in isolation.

Modern marriage is often just a chair with two legs! Fight for as many people in your extended family as possible. It’ll mean a lot more as you get older.

Hmm, speaking of gender… Ideas about men and women are so beat into us from so early. We digest them and then we begin endlessly sorting and treating people accordingly. Try a thought experiment, and in your mind, put a man’s face on your girlfriend. Go all Face/Off. (Sure, yes, it’s fine if you decide your girlfriend looks like a younger Nic Cage.) How would you talk to your girlfriend as a boyfriend? Would you be more direct, less conciliatory, less forgiving? Or would you be the opposite? Try leaning into that. Try something new in how you communicate.

I’m ignoring the whole part of your letter where your friends apparently talk about how much hotter your girlfriend is than your friend and are weirded out that your girlfriend is hot but somehow also insecure, LOL, because it’s a weekend and I’m going to yoga now.

xo

The Concessionist is an adult human in New York City who is somewhat worn down and willing to make a good number of sacrifices for a peaceful life. Is it decision fatigue? Or just ennui? That’s probably a question for a psychiatrist. Anything else, ask me. I agree to keep your identity between us.

• I Hate Myself Because I Don’t Work For BuzzFeed

• In Praise of Getting Back Together with the Dude who Dumped You

• How to Make Your Girlfriend Like You (Again)

New York City, March 12, 2015

★★★★ Light reflecting off the top of a tower off by the river beamed through the living-window and raised white pixels on the wall under the hanging wooden lattice. Outside the morning was October. Workmen were knocking down the scaffolding; a faded gibbous moon was descending in the clear sky. The three-year-old set off for preschool at a jog. A vehicle maneuvering in a parking space shook up a cloud of grit that got caught by the wind and flung in the face. The dust crunched disgustingly on the teeth and itched inside the shirt collar. An empty can rolled in a loud arc on the sidewalk. It seemed possible that the gusts on the way back from the river would blow away the dust in a sort of air shower, but all they did was deliver a piece of sharp debris to one eye. A pair of salt trucks and a Bobcat were attacking the snowmass still left on 70th street. The sun shone so strongly that the world flashed orange with each eyeblink. Down on Prince Street water was trickling onto the sidewalk from what was incredibly still solid sheet ice inside the fence of the Old Cathedral School. The sky stayed autumn-sharp all through the day, into the crispness of rush hour. The snow was almost — almost — gone. Up on Broadway, a new-looking pothole lay in the curb lane. The wavy, boxy shape of a copper-kissed tower was nested in the larger mirrored box of the glass tower across the avenue.

Ellis Island After the Flood

by Jordan Larson

For more than thirty years, long after its time as the “gateway to the American dream,” Ellis Island sat empty and abandoned in New York Harbor. The island didn’t have much of a purpose after the Immigration and Naturalization Service relocated to an office in Manhattan in the nineteen fifties, and it was declared surplus federal property until a decision could be made about what to do with it. Eventually, after becoming part of the National Park Service’s Statue of Liberty National Monument, Ellis Island was restored and given over to tourists in 1990. Ferries from New York and New Jersey now usher millions of visitors over to the twenty-seven-and-a-half-acre island every year, where families trace their lineage and pose for photos with the Manhattan skyline. The distinct French Renaissance style and pristine red-tiled roof of the Main Immigration Building give the illusion that the place hasn’t changed much since the early twentieth century; Inside, the Immigration Museum’s three stories stand as testament to Ellis Island’s years of inspection lines and medical exams. But as much as it seems frozen in time, and for all the work put into making it a historical landmark and tourist destination, Ellis Island is disappearing. The destruction of Hurricane Sandy, which left the island briefly underwater and caused millions in damage, has made it clear that Ellis Island history is not static, nor is its presence a given. Climate change is working its way into Ellis Island — its structures, museum exhibits, and, subtly, its narrative. The landmark’s damage and repairs are now a tug of war with nature, as well as a battle to determine what constitutes history and why.

When Hurricane Sandy hit New York and New Jersey in October 2012, sea level at the Battery peaked at fourteen feet, nine feet above the already high tide.Nearly all of Ellis Island — and three-quarters of nearby Liberty Island — were covered by floodwaters. Buildings on both islands were flooded, resulting in an estimated seventy-seven million dollars in damage. Though the museum’s photos and artifacts were largely untouched by the storm — floodwaters reached only the top step of the Main Immigration Building — the loss of climate control systems meant that nearly all the museum’s historical artifacts had to be evacuated. It took the specially convened National Park Service Museum Emergency Response Team six weeks of cataloguing and packing to move more than one million artifacts to a Park Service storage facility in Maryland, where they will remain until repairs on the Main Immigration Building are completed in late 2015; while Ellis Island and its Immigration Museum reopened to visitors in October 2013, they remain largely devoid of history and its objects. As the New York Times noted last June, “many of the artifacts that evoke the immigrant experience — passports, steamship tickets, letters of introduction, faded suitcases, original photographs and traveling outfits — are missing.”

For the two million who have visited Ellis Island since it reopened in a year and a half ago, the false tasks of separating humans from nature, and history from the present, have been made more difficult. The Immigration Museum stands largely empty, with abundant signage reminding visitors just why that’s so. Even the Museum’s exhibit on Hurricane Sandy’s impact is mostly composed of space, its minimalism only highlighting the results of evacuation. “Weathering the Storm,” tucked away in the third floor temporary exhibit space, is a sparse and somber display of photographs and text which document the damage caused by the storm and how the National Park Service responded. But, above all, the exhibit is there to reassure the public — an optimistic apology of the corporate “please excuse our mess” variety. “Luckily, the Statue of Liberty and the historic Ellis Island buildings suffered little or no major damage. Thus began a cleanup and recovery operation that continues to this day,” reads the cheerful exhibit copy. “The National Park Service is not only rebuilding, but rebuilding in smart, sustainable ways. NPS staff is deciding how to meet that challenge.” (The museum’s café actually does have a sign that reads, “Please pardon our appearance as we remodel our Café due to Hurricane Sandy.”) Other exhibits, like “Ellis Island Chronicles,” contain similar messages, like one poster preemptively asking, “Where are the Artifacts?” The exhibit “Treasures from Home” stands dark and blocked off from museum-goers with makeshift barricades, holding only mannequins and empty displays.

On the Main Immigration Building’s lower levels and the surrounding structures, the threat of climate change is being built into electrical and mechanical systems necessary for sustaining the museum. When possible, much of the essential equipment — like boilers, electrical transformers, and chillers — is being moved up out of the floodplain. A twelve-foot mezzanine has been built in the island’s powerhouse in order to lift equipment off the ground level, and the Main Immigration Building’s basement will now be a bit emptier, though weather-proofed items like air handlers will remain there. As Parks Service project manager Robert Parrish told me, it’s necessary to ask, “How is our conducting this project going to affect climate change, but then also how is climate change, rising sea levels, going to affect the project in the long run?”

In the course of making those decisions, certain items and periods of history have had to be sacrificed. In order to begin restructuring, repairing, and replacing infrastructure, the project underwent a Section 106 review to assess the impact of such changes on the historical fabric of Ellis Island. Certain changes — like moving large air handlers up into the museum proper — were impossible, but replacing boilers that dated back to the island’s nineteen eighties renovation were acceptable. After all, Ellis Island is about preserving certain pieces of history, not all of it.

Ellis Island is a tribute to the history of twelve million immigrants and their descendants, but it’s also a tribute to boundaries. The island is demarcated into various parts and jurisdictions: A 1998 Supreme Court case ruled that the island be shared by New York and New Jersey; the former controls the original 3.3 acres that was acquired by New York in 1808, while the island’s remaining 24.2 acres — created with landfill from New York’s subway system — is considered part of New Jersey. Ellis Island is also subdivided into three parts, as multiple islands and extensions were added between 1890 and 1934. The Park Service manages the first island, including the Main Immigration Building and museum, while Save Ellis Island, a non-profit, manages islands two and three.

Across the ferry dock to the southwest, Save Ellis Island has responded to Hurricane Sandy by opening the 22-building hospital complex to visitors for the first time in half a century. The idea to open up the hospital complex came in the wake of Sandy, which destroyed the hospital exhibit in the Immigration Museum, according to Janis Calella, president of Save Ellis Island. About two-dozen life-size photographs now plaster the walls and windows of the decrepit hospital complex, once the largest such medical institution in the country. The work of French artist JR, Unframed — Ellis Island features portraits of immigrant children and nurses, doctors and patients. The installation both seeks to collapse time and make it more present; even with the intruding, realist photographs, viewers are constantly reminded of the distance between themselves and those who passed through the hospital’s walls decades ago. Closed since 1954, the hospital buildings have mostly been left in the state in which they were found, strewn with detritus and damaged from half a decade of weather and wear. Because of the buildings’ exposed state, Unframed, meant to substitute the museum’s missing artifacts, is even more susceptible to natural forces. As the Times notes, “Nature has already transformed some of the images: On the ancient lockers, rust seeps through the white uniforms of the nurses; people in a group of immigrant detainees appear nervous in a decayed room open to the lapping river.”

“Thinking about natural history and human history is like looking at one of those trick drawings — a skull that becomes a seated woman, a wineglass that becomes a pair of kissing profiles — it’s hard to see them both at the same time,” Rebecca Solnit writes in her book Savage Dreams. In the case of Ellis Island, we may be witnessing something closer to a collapse of human and natural history, in which the latter drowns out the former.

This negotiation between human and natural history has a long tradition within the National Park Service, which has been responsible for Ellis Island for as long as it’s been attracting tourists and putting on exhibits. Yosemite, the country’s first national park — established as a state park in 1864, before the creation of the Park Service in 1916 — is a paragon of the picturesque and the sublime. As Solnit writes, in the late nineteenth century, after white settlers first “discovered” it, Yosemite became a tourist attraction for elites and naturalists alike; the attention of future Sierra Club founder John Muir and photographer Carleton Watkins were critical to the area becoming a protected park and national symbol. But what also led visitors and benefactors to conceive of Yosemite as a pure and sublime place was the concept of landscape art, a fairly recent occurrence originating among European elites. The birth and subsequent popularity of representational art which took landscape, rather than humans, as its subject, in turn led to a newfound appreciation of nature. Sightseers began looking upon nature much as they would look upon a painting, Solnit argues. Nature — at least when it’s beautiful — is cast as static, unchangeable, and, most importantly, separate from humans and our history. And while Yosemite is still considered the epitome of natural beauty, a place which Americans have a duty to visit and enjoy, the fact that Yosemite was inhabited by the indigenous Ahwahneechee people before white settlers invaded in 1851 has gone ignored by history’s dominant narrative. Treating Yosemite as a singular and untouchable object, devoid of a history or a future, bars us from grappling with its history of invasion and forced location of those who lived there before it became a live-action painting.

This is why the Park Service’s more recent management of primarily historical, rather than natural, sites — like Ellis Island, the USS Arizona monument, or George Washington’s birthplace — makes perfect sense: The agency has always treated natural parks as museums. But whether the landmark in question is a natural park or a historical site, treating it as a museum has the same effect, jettisoning space away from us and our present. As Edith Wharton noted, “Museums are cemeteries, as unavoidable, no doubt, as the other kind, but just as unrelated to the living beauty of what we have loved.”

Such demarcations — between human and natural history, and between beautiful nature and the rest of it — remain a guiding principle, and source of tension, within the Park Service. As National Park Service Director Jon Jarvis wrote in a 2010 climate change response strategy, “I believe climate change is fundamentally the greatest threat to the integrity of our national parks that we have ever experienced.” But how do you protect nature from itself? Nature, in this context, gets qualified; agency-protected nature is sliced away from the nature surrounding it. Fearing the nature that has been destroyed by humans, the agency prioritizes saving the nature that’s only managed by humans.

Of course, certain boundaries are necessary; not all forms of cultural or natural history are worth preserving. But the question of who gets to make those decisions, and why, remains. After all, historical symbols and places are meant to remain always, reminding us of exactly what we want them to remind us of, forever.

It’s unclear exactly when rising sea levels may make visiting or maintaining Ellis and Liberty Islands impossible. It could be as soon as fifty years, but will likely not happen during our lifetimes. “In a place like Ellis Island, and even Liberty Island, there’s only so much resiliency you can do because of the historic nature of the buildings,” says Parrish. “We’re not gonna put the statue up on stilts.”

The Statue of Liberty National Monument is only one of more than one hundred national parks directly threatened by climate change, in the form of rising sea levels and storm surges. As the Union of Concerned Scientists lamented in a report published last spring, “the geographic and cultural quilt that tells the American story is fraying at the edges — and even beginning to be pulled apart — by the impacts of climate change.”

But the relationship between nature and history isn’t a zero-sum game; the two are thoroughly inextricable. The enforcement of boundaries that’s inherent to much of formulating history, protecting National Parks, and designating meaning doesn’t seem to be quite holding up against the forces of natural change. At work on Ellis Island now is the realization that stasis is not a given — nor is it natural. You can’t keep things the same without changing them a little. And just as history is always being made, preserving history — and nature — is a creative process.

Photo via Wikimedia Commons

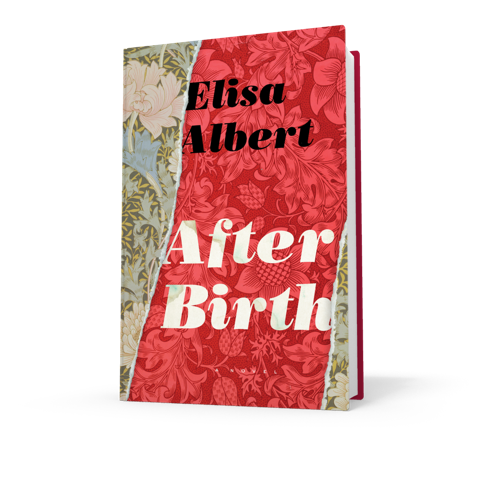

Read the First Chapter of Elisa Albert's After Birth

by Awl Sponsors

Below is an excerpt of the first chapter of Elisa Albert’s new novel, After Birth. Order your copy now at this link.

1.

November

The buildings are amazing in this shitbox town.

Late eighteenth-century row houses. Dirt-basement Colonial wonders. High-ceilinged Victorians. Clapboards. Wood stoves, crappy plumbing, gracious proportions. Faded grandeur, semi-rot. Clawfoot bathtubs with old brass fixtures rusty as hell. Here and there the odd sparkling restoration. Someone’s nouveau riche marble kitchen.

Here’s my favorite: four-story brick, three windows wide, with a Historical Society Landmark plaque. Built in 1868. Elaborate molding painted many shades of green. My friends Crispin and Jerry spent the better part of ten years rehabbing it. They’re on sabbatical this year in Rome, those bastards. They sublet to this amazing poet with a visiting gig at the college. Mina Morris. I’m a little obsessed with her, by which I mean a lot, which I guess is what obsessed means.

The parlor curtains are open and the lights are off.

I drove Crisp and Jer to the airport, and Crisp handed me an estate-sale mother-of-pearl cigarette case perfectly filled with nine meticulously rolled joints.

I teared up.

Medicine man, please don’t go.

Listen. He lifted my chin and met my eyes in this avuncular way he has. You’ve come a long way. You’re going to be fine. He said it slowly, like I might be very old, very stupid, or both.

I have five joints left.

The baby’s first birthday approaches. Still, there are bad days. Today’s not so bad. Today I have fulfilled two imperatives: one, the baby is napping; two, we are out of doors, a few blocks from home.

Anyway, Mina Morris. Crisp gave me her contact info because we’re supposed to be landlord proxy, Paul and I, take care of anything that comes up with the house while they’re gone.

Mina Morris. Quasi known as the bass player from the Misogynists. Girl band, Oregon, late eighties. Lots of better-known girl bands talk about having been influenced by them.

Cold this week, and dark so early. Late afternoon and the light is dead. So it begins: months of early darkness and cold. November again, back around to another. Last November a nightmare blur of newborn stitches tears antibiotics awake constipation tears wound tears awake awake awake limping tears screaming tears screaming shit piss puke tears. My weeks structured around a very occasional trip to the drive-through donut place near the mall, baby dozing in the back. Idling in the crappy old Jewish cemetery across the highway, heat cranked, reading names on crooked headstones, sipping an enormous, too-sweet latte, tapping at the disappointing glow of my device.

Faint whistle. There goes a train. To the city, probably. Four fifteen. Too late for the baby’s nap now, too close to bedtime. But I’ve given up trying to control this shit. If you have an agenda, any needs or desires of your own (like, for example, to take a shower, take a dump, be somewhere at a given time, sit and think), you’re screwed. The trick is to surrender completely, take your moments when you get them, don’t dare want for more.

Mina Morris: erstwhile poet, almost rock star. Here, in Crisp and Jerry’s house. Gives me an obscure little thrill, it does. I want to be friends.

A third-floor light goes on, and simultaneously the baby starts up with the whimpers. I take my cue. Keep the stroller moving, always moving, a reflexive animal sway. Respite over. Maneuver down the block toward the river, up Chestnut, and on home. Put some cheese on crackers and call it dinner.

Another day gone, okay, and I get it, I got it: I’m over. I no longer exist. This is why there’s that ancient stipulation about the childless being ineligible for the study of religious mysticism. This is why there’s all that talk about kid having as express train to enlightenment. You can meditate, you can medicate, you can take peyote in the desert at sunrise, you can self-immolate, or you can have a baby, and disappear.

I’m not interested in anything.

Ari. Babe.

Which might make sense if I was all consumed with thoughts of baby-food making and craft projects and sleep-training philosophies and bouncy-chair brands, but I really can’t get all that excited about any of that shit either. So basically I have no idea what to do with myself, Paul.

Babe. Give it some time.

Fine, I mean, great, but how much time? He’s one, Paul.

Exactly, babe, he’s one.

You should just send me away someplace. You should just take me out back and shoot me.

Ari.

Wire, "Split Ends"

The cascading music feeds are good for finding new songs but especially new people. This is great, mostly, but makes the sound of absolute assurance feel like a rare treat. Pink Flag is thirty-seven years old.