What Are You Going To Be Blamed For By The Future?

“In 2115, when our descendants look back at our society, what will they condemn as our greatest moral failing?”

— My guess would be either eating animals or being so wrapped up in trash television that we couldn’t just see the actual episodes, we had to have talk shows appearing immediately after the program in which what we just watched was analyzed by C-list celebrities and whoever else happened to be free that evening. But this also assumes that there will still be a society around in 2115 to look back with derision on our foolish 21st century choices. My sense is that there will not be, because we will have destroyed it all by then. That’s right, suck it, you self-righteous pricks of 2115! We’re going to fuck it all up forever before you get a chance to cast aspersions on us! WHO’S MORALLY SUPERIOR NOW? What? You don’t have time to answer me because you’re busy running from fires and killer robots in your resource-scarce hellhole of a post-apocalyptic environment? Oh well.

Errors, "Slow Rotor"

Errors’ Lease of Life is out now and this track will give you a pretty good indication of whether or not you’ll like the album. They’re on Mogwai’s label if that moves the needle for you one way or the other. I like it: There are so many different sounds here that remind me of other things that the whole winds up being something both familiar and new at the same time. Of course, maybe these sounds frighten or scare you, or anger you in some way you cannot quite identify, bringing to the surface emotions you try so hard to keep tamped down inside your dark heart each day. Music is funny like that. You never know what it’s going to do to you. Anyway, if this song does not make you want to hurt people because, as previously discussed, it liberates the rage you expend so much energy in containing, enjoy. But if it is a problem, probably best not to play it.

Toward a Theory of Normcore Food

by Johannah King-Slutzky

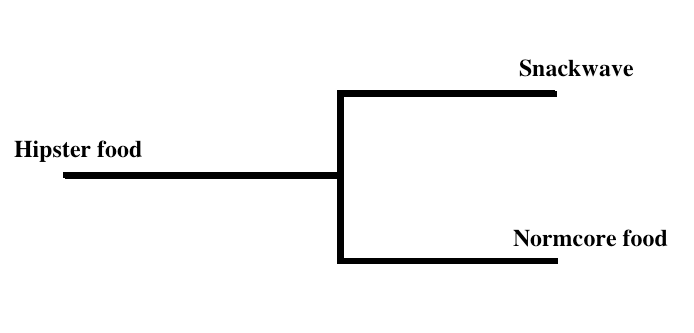

Small-batch pickles, Greek yogurt, and quinoa are all high-stakes trendy foods with loads of moral and aesthetic baggage. We ingest them to prove to ourselves that we are ethical by way of being health-conscious, multicultural, hard workers. Of course, the labor required to produce and consume a pickle won’t have any measurable effect on the health of your body, the quality of your soul, or the degree of your authenticity. This constellation of foods, which might be crudely labeled “hipster food,” are the means by which our sense of goodness is outsourced through our gut.

The antithetical culinary trend of hipster food, snackwave, seizes on its puritanism and refutes it through slovenliness, shopping mall imagery, and pro-capitalist branding. It is the first prong in the anti-hipster food backlash. As Hazel Cills and Gabrielle Noone write in The Hairpin, snackwave “trickled up from Tumblr dashboards” to counter “Pinterest-worthy twee cupcake recipes.” It is chiefly defined by excessive consumption of junk food and is often couched in the doctrine that women, especially, can do whatever they want to their bodies. An important element of snackwave is its individualism: the meal is communal, the snack is individual.

Normcore food will be the second prong in the anti-hipster food backlash. Normcore and snackwave, though opposites, are both cultural formations that will teach us how to finally stop eating kale. There have been a couple anemic attempts to define normcore food, and they are usually wrong. For example, people who believe normcore food is just junk food done up in a chef hat — your David Chang-type cuisine — are confusing it with typical hipster fare. Bon Appetitmade a better go of it with their April Fool’s Day slideshow, which included items like yogurt and chicken fajitas, and at least one food blogger got it right when she identified the BRAT diet plus plain chicken and bok choy as normcore. In the realm of fine cuisine, The New York Times has unknowingly alluded to at least one normcoreish food movement in a trend piece on “refined slob” nineties food writer Laurie Colwin. Besides normcore being a running joke, it is also very attractive, as increasingly elaborate (or else humblebrag-y) food exhausts itself and gives way to a minimalism that is not regressive or folksy.

If normcore fashion is not just hipsterism made over in worse nineties clothes — which is a common critique — normcore food should also have its own menu. Specifically, it must exclude any variety of trend-forward food: kitsch Americana, artisanal products like pickles and jams, and snackwave-like excess. As with its fashion equivalent, the goods must be ugly and plainly dressed.

Normcore food is all of the following:

1. Ugly

2. Homemade but not artisanal

3. Would have been popular in the early nineties without becoming a nostalgia fetish item

4. Healthy but not cleansing

5. Can be made or purchased in batches large enough for a family but is usually eaten alone

6. Might use ethnic ingredients, but never in order to claim authenticity

Like snackwave, normcore food takes its cues from the internet. But where snackwave revels in brands like Taco Bell, normcore food is clean, anodyne, and a little uncanny, just like the rolling pastures on Stonyfield yogurt cups. Normcore is not Molly Soda Tumblr; normcore is The Jogging Tumblr. Normcore is #aloewave. Normcore is Google Maps. Though both normcore and snackwave play with capitalism, anonymity, and technology, while snackwave is defined by excess and cliche, normcore is minimalist and inoffensively healthy.

These principles don’t just make dialectical sense; they also reproduce normcore fashion’s source texts. Although normcore’s boundaries are contested, one premise about normcore fashion has remained universally unchallenged: Jerry and George would have worn it on Seinfeld. The question that naturally follows is, What would Jerry Seinfeld and George Costanza have eaten? Having watched a lot of Seinfeld and also having researched “Jerry Seinfeld food” on YouTube I can tell you: tuna salad on toast, not-actually-spicy kung pao chicken, single-serving take out soup, Junior Mints, brandless cereal, and scores of dehydrating pretzels.

In 1998, Jerry Seinfeld had a comedic bit — the gist of which is “What’s up with supermarkets??” — that exemplifies exactly how Jerry Seinfeld approached food in the nineties. He admits to feeling compelled but befuddled by health consciousness, literally dazed by the organization of aisles and inaccessible exits, and challenged by the folksy received wisdom that has since become de rigueur for foodies. He is particularly baffled by seasonal fruits. In other words, Jerry Seinfeld is inexpert. He is also (unlike practitioners of snackwave) not polemic. He wants to be healthy but is neither forward thinking nor atavistic enough to adopt the ethos of “fat free” or organic. Seinfeld’s food is also multicultural but never authentic: George eats spicy kung pao but reverts to milder stuff after sweating too profusely in the presence of his boss; Jerry and Elaine visit a soup stand for ambiguously ethnic food on the go. The group’s snack food is not indulgently deep fried, like potato chips; they eat pretzels and mints. Jerry and co. are always eating standing up. Even at the diner, they come and go interchangeably. There are no five-seater golden turkey kitschy-nostalgic American meals on Seinfeld.

The second widely embraced source text for normcore is a certain kind of internet art — minimalist, often inspired by “postinternet art,” and collective or anonymous. The Jogging, a user submission-based net art Tumblr founded by Brad Troemel and Lauren Christiansen, is definitely normcore. (The normcore/The Jogging connection is kind of intuitive, but if you want further proof, Art F City claims that normcore started out as The Jogging co-founder Brad Troemel’s in-joke about DIS Magazine.) This kind of net art is fixated on food and therefore makes an ideal library of what normcore food is or will become. Going by culinary images on blogs like The Jogging, normcore food is unattractively butchered salmon, dry cornflakes, white onion with Jell-O red marinara, and kebabs. The K-Hole “Youth Mode” report’s normcore section also features a very Jogging-y photograph of a Del Monte fruit sticker slapped onto a banana-yellow snake. These foods are ugly, inexpert, and neither healthy nor unhealthy. Like the kebab, they are occasionally ethnic but not fetishistic. Not that these foods should be taken literally — no one is suggesting you eat a whole unchopped onion out of a frying pan — but read in the right spirit, these images are a legible normcore food archive.

These qualities are reproduced in normcore fashion. In her New York Magazine article, Fiona Duncan introduces readers to normcore when she admits to no longer being able to distinguish art kids from “middle-aged, middle-American” tourists:

Clad in stonewash jeans, fleece, and comfortable sneakers, both types looked like they might’ve just stepped off an R-train after shopping in Times Square. When I texted my friend Brad (an artist whose summer uniform consisted of Adidas barefoot trainers, mesh shorts and plain cotton tees) for his take on the latest urban camouflage, I got an immediate reply: “lol normcore.”

One salient feature of normcore is that it is middling: middle-aged, middle American, and implicitly upper middle class. Normcore is also a peculiar blend of labor and leisure. Wearers look like they “just stepped off an R-train” (meaning they have been busy) yet they look like tourists (they have been on vacation). This labor/leisure mixture is reproduced in normcore’s affection for sports. Normcore sportiness, like Duncan’s apocryphal Times Square tourist, looks physically active but not productive. Three icons of normcore are the white athletic sock, the baseball cap (extra points for Nike logo), and the Nike or Adidas track pant — all generically athletic, usually paired with something that neuters the wearer’s capacity for physical exertion, like stiletto heels.

Examining the stilettos with gym-sock as normcore synecdoche, we can see what might make this middling athleticism attractive. The stiletto/sock combo appears cobbled together in a way that — to borrow food diction — you might call homemade but not classic. That is, it is inexpert — neither professional nor folksy-conventional — and uses genuinely sentimental ingredients without aiming for authenticity. The stiletto-with-gym-sock combines glamorous working-girl imagery (popular in fashion spreads since 1960, when young women began to live and shop outside the family) with lumpy apparel you can buy in packs. Gym socks are not just ambiguously “dad-like,” they’re what a family buys when it shops in bulk. So the stiletto/gym sock combo alludes to at least three self-moderations: individualism within the family, leisure within labor, and constructed inexpertise.

Normcore foods are attractive because they’re a middling response to the aesthetic and political problems posed by the hipster. The worst part of hipster food is its fetish for authenticity. Not only is it pretentious, it can have real world effects like raising the price of quinoa above its farmers’ purchasing power and gentrifying low-income black people out of purchasing the formerly affordable greens that are a staple of soul food.

A case study in normcore food is Stonyfield Cream Top yogurt. Stonyfield yogurt is way less interesting than other kinds of yogurt. It looks like the Windows XP home screen. It’s the Times New Roman of yogurt. And yet: Snacks are in. Yogurt is a snack. Unlike other zeitgeist-y snacks, however, Stonyfield yogurt isn’t obsessed with itself. It’s not curated, and it isn’t a bottomless pit of teen nostalgia. Stonyfield yogurt is a snack that won’t make you feel clean or sad. Therein lies its mystique. It doesn’t trade on any ethnic subculture. It also bridges the gap between youth (e.g. snackwave, David Chang couture cereal-milk ice cream) and responsible adulthood (Whole Foods, small plates, farms). Stonyfield yogurt will be THE yogurt of the late twenty-tens because it is post-hipster, yet offers an alternative to the anti-authoritarian individualism and wryness of snackwave.

Stonyfield not “artisanal” (like Greek yogurt) but it’s not junk food; it’s family food your mom might’ve purchased but is often eaten alone, on the go; and it belongs to, yet refutes, the ideology of snacks — which are adolescent, unhealthy, and eaten alone (or at least not at the dinner table). Cream-top yogurt is a snack that is self-contained, minimalist, and unsuitable for a sleepover.

Similarly, SodaStream is normcore because its bottles looks like Clip Art — and a food product is always normcore if its packaging looks like it was designed in Microsoft Word. Additionally, SodaStream is photographed in generic stock image style, straight on or sometimes at a slight downward angle, but always in a vacuum. Finally, SodaStream is homemade but not artisanal; vaguely ethnic (seltzer is Jewish); and can be made for a family of four but consumed alone.

Boring fruits like apples, oranges, bananas, cherries, apples (anything stock enough to appear on slot machines and candy) are normcore. Kale, collard greens, lychee, mango, etc. are not. Peas are normcore. Red leaf lettuce is normcore. Iceberg lettuce is not normcore. (Too kitschy.) Generally if you can tell me about a fruit or vegetable’s cultural history it is not normcore. On the other hand, prepared foods are usually not normcore because normcore must be inexpert and family oriented. Lean Cuisine, which is disgusting, is normcoreish. If the normcorer must eat prepared food, he should eat Lean Cuisine.

Fast food can be normcore if consumed in moderation. Taco Bell is never normcore (too snackwave, too ironic), but McDonald’s and Burger King can be normcore. McDonald’s and Burger King are generic but not kitschy, “wacky,” or borderline artisanal. Mega brands like McDonald’s are consistent with normcore because they’re culturally unspecific; they don’t make you feel like a fuck-it-all underdog. Fuck-it-all underdog is never normcore. Applebees is not normcore; gas station food is not normcore. The irony and kitsch potential is too high, and normcore is hesitantly sincere or else incredibly dry. Normcore food, like normcore fashion, is urban. That means many rural and suburban dining choices are not normcore.

A handful of foods are normcore but not uniquely so. Normcore is okay with this. This means Coca-Cola, cheap beers like Budweiser or Corona with lime, and bland roast chicken are normcore. The New York Times coverage of young New York writers’ surging interest in nineties ‘slob’ food writer Laurie Colwin includes a large inventory of potentially normcore foods. The article mentions creamed spinach (no, too kitschy), baked mustard chicken (yes, because limply spicy mustard; no if made with Panko crumbs), black beans (yes, black beans are ugly beans), lentil soup (no), and potato salad (indeterminate). Likewise, most normcore food is homemade with standard but inexpertly combined ingredients. Examples include curried chicken salad made with copious mayonnaise, bean salads made with ugly beans (like kidney beans), or ants on a log made with hydrogenated peanut butter or cream cheese. Also, lots of nineties-style tupperware like this.

So what? Is normcore food all a big fart that goes nowhere? Probably. Maybe delis will sell more curry chicken salad. Maybe the canned tuna market will shoot up. For sure, Greek yogurt is fucked in the long term; that market is saturated. But normcore food is not a branded movement, so industry-based change will be limited, and snackwave will offset any normcore anti-junk food zeitgeist. Normcore food is more significant as an index of our puritanism, whose contemporary cultural relevance is bizarrely unnoticed. Normcore is not purely puritanical; it’s too middling, and it doesn’t want to purify so much as stabilize. It’s about self-moderation. That’s why it mixes mega brands like Nike with nondescript unbranded white shirtsleeves, or why it neuters high-end luxury goods with tube socks.

A lot of cultural critics can’t see this, partially because the dividing line between “normcore” and “hipster” is muddled when it comes to clothes. For example, many people wrongly assume mom jeans are normcore. They’re not; they’re the same stuff American Apparel has been peddling for years. This is one of the ways that thinking about normcore through food, instead of fashion, can be helpful. In food, these distinctions are clearer. We know juice and kale and quinoa are cleansing, puritan, and that chicken salad with mayo isn’t. It’s easier to take notice of our puritanism through food. So long as puritanism remains culturally viable, normcore will be attractive.

New York City, March 22, 2015

★★ The sun and the food trucks were out, in defiance or denial of the intransigent cold. Exiting the children’s concert, the boys mountaineered the steps outside Alice Tully Hall, clambering over sharp dried-salt sneaker prints. Young women bundled up in scarves sat at the very top, eating cart food from foam clamshells. Even a Mister Softee truck was attempting to make a day of it; the three-year-old wanted share in its unfounded optimism, but settled for a pack of Life Savers from the newsstand. The bright superficial reflections among the buildings went from white to amber to red.

Heems At Home

by Giri Nathan

Forty-eight hours before jumping on stage at the release party for his new album Eat Pray Thug, swinging his mic at the crowd like a baseball bat, and skip-hopping around the stage with his sweat-soaked hair flopping side to side, Himanshu Suri was coughing up phlegm under a flowery velour blanket at his parents’ house in Long Island. Laid low by the flu, Suri — better known as Heems — still graciously agreed to have me over to show me the new record on vinyl.

Eat Pray Thug is more confessional and direct than Heems’ output in the group Das Racist: There is nothing arch or oblique in the lyrics of tracks like “Flag Shopping”:

We’re going flag shopping for American flags

They’re staring at our turbans

They’re calling them rags

They’re calling them towels

They’re calling them diapers

They’re more like crowns

Let’s strike them like vipers

After offering me a Diet Coke (which I declined) and some homemade biryani (which I devoured), we talked about his frustrations with the Indian-American community, his racial and spiritual identity, and what it’s like for a successful rapper to move back home and work a day job in advertising technology.

Do you think being an Indian-American artist gives you a certain kind of mobility as an artist?

I can chum it up with white dudes and black dudes. Being Indian I think you have to navigate a lot of worlds. As a person of color, you identify with black people here, and that experience. But because of selective immigration — because so many of us arrived here with masters and PhDs in engineering — those things make it easier to navigate the white world, and the academic world. But a lot of the South Asians coming here now are rich people. And what it does is leave the working class Indians in the dark. Basically, we spent a lot of the nineties being like, “Hey, I’m not Apu, I’m not just a character.” Twenty years later, Indians are associated with hedge funds, doctors, and pharmacies. The important thing, I think, is to remember the working class. Nobody’s really out there telling their stories or speaking on their behalf. It’s like Manhattan Indians don’t really care about Queens Indians.

You’re now out here in Long Island. What’s it like being back at home with your parents?

Basically I was chipping in on the mortgage here, and also paying rent in Brooklyn, and that just seemed dumb. I wanted the space. And my sister and her husband and my two nieces were here, and I had the opportunity to spend more time with them in one house.

You’re very close with your family. Indians tend to have conservative social mores, and your music often dives into sensitive subject matters. Has this put any strain on your relationship with your parents?

In large part, the words in rap music are so quick they don’t even really understand what I’m saying. Obviously they speak English, but it’s not their first language. I told them that I was talking about my vices and struggles with dependency on the record. I bet they’d prefer that I not be public about these things, but the way I explained it to them, I have the opportunity to be a voice for the community and to help young people. In the brown community we don’t really talk openly about these things. The general vibe is like, if you do have problems, don’t talk about it, don’t let people know. There’s total shame. But there’s so much of that in our community, and it’s something we need to talk about — because we don’t talk about it, and it gets worse and worse. If me being honest about it might help a young kid who struggles with anxiety or depression or is dependent on substances, I feel better about my work. Ultimately that’s the kind of work I want to make, work that helps people, not just “turn up at the club” type shit.

But I like turning up at the club too.

We’ve talked about how the Indian community tends to suppress conversations on crucial issues like mental health. What’s your other big critique?

Apathy. It’s bad. There’s too much of it in the Asian-American community. And there’s not enough appreciation for our black brothers and sisters, and the civil rights movement that made it possible for us to even be here in this country. There’s just so much apathy when it comes to race or politics. The general thinking is, “How will it affect me and my taxes?” There isn’t enough helping your next man. We’re so eager to show people that we’re doctors, we’re smart and successful and have money, but we act as if the working class doesn’t even exist.

You’ve talked about working on a novel about the Indian working class experience.

Jhumpa Lahiri is half the reason — maybe the whole reason — I want to write a novel. But her concerns were too upper class. Her characters were the children of professors, engineers. I want to tell the stories of the working class.

You seem close with a few novelists, like Salman Rushdie and Teju Cole.

They’ve been totally supportive. I haven’t gotten to a place where I can really tap into him in that sense, because I haven’t written any of it, but when it is written, Teju’s been kind enough to let me know that he’ll look at it. And that’s a good set of eyes, you know?

Despite having visited the country regularly, I have yet to explore India beyond the small towns where my relatives live. What would you recommend?

Goa. Do you like the beach? Do you like parties? Do you want to be somewhere it’s a blend of Indian people and international people? That’s Goa.

When I was younger, I was begrudging in my approach to Indian culture, but at some point I realized its richness and found myself actively wanting to explore it. Did you have a similar turning point?

Even from a super-young age, I was patriotic in a sense. I remember when I was little, I had my mother pick me up an Indian flag. Now I have the Indian flag hanging behind my door. It was even weird, to a certain extent. Because when you’re in the Indian community, there’s no need to be nationalistic, because everyone’s Indian. So I don’t even know why. I think because we had the India Day parade every year so that would always be an exciting time as a child. I would go to that parade every year, and I would go on the floats too — and the afterparties at the club that inevitably end up in a fight.

I wanna hear more about these afterparties at the club.

I was just saying how fortunate I am that I started with an audience that was largely white. Now I have an audience that’s growing, in large part with the Indian, Pakistani, Bangladeshi kids. But it’s better to come in that way and then move in this direction, than to come out the gate as “the Indian rapper,” because it’s like, where does that trajectory go? You play the India Day Parade afterparty once a year and that’s it. That’s the gig. So I’m hella fortunate.

Tell me about your day job.

I work for Moat, they’re the best in ad-tech analytics. Some people call them a disruptor, as far as ad-tech goes. I took that job, but I don’t really need it, you know? I figured it’s an opportunity to learn something I don’t know that much about. It used to provide structure but now I don’t go into the office anymore, I work from home, because I’ve had so many meetings now, with the album coming out. I got the job right when I got the release date, so it’s been kinda chaotic.

Were your parents nervous when you first quit your job as a Wall Street headhunter, way back at the birth of Das Racist?

They’ve been super-supportive. I was hella good at the headhunting job. But at that time it just wasn’t really the best look for me. Because certain doors were opening up in music, I just decided to end it there. But I’ve spoken to the company and the essentially the owner was like, ‘There’s a desk for you whenever you want it.” When I was on the cover of the Village Voice, I got a text from him two days later saying “I don’t think you wanna work here.” But I told him, if you let me run your Bombay office, I’ll do it.

Tell me about your spirituality these days.

There’s a Hindu temple here, about ten minutes away. And I’m spending more time at the gurdwara (a place of Sikh worship) too, and I’ve never done that before. But the temple’s basically a baseline. Every Sunday night, we’d be out there. And we were around for the beginning of it. So it’s a pretty important part of my life. This year my own personal spirituality has been a little more Sikhism than before.

How does your spirituality vary from that of your parents?

One of the things I love about Hinduism is it’s so much, it’s so big. My parents, their Hinduism is far different from mine. I love that about the religion — there are so many different types of it. Theirs is definitely more ritual-based, these are the days you don’t eat meat, and you fast on this day, and these are the holidays you celebrate. But me, I look at the religion both from a ritualistic standpoint and also like a theological, more academic standpoint, having read a lot of the texts. So sometimes I’ll say something, and my parents will be like, “That didn’t happen, that’s not true.” And I’ll be like, “Yo, trust me, I read it.”

What are your favorite Hindu texts?

I’m a big fan of the Hanuman Chalisa, and the Sunderkand. They’re both devotional to Hanuman.

I loved reading about Hanuman. He was one of my favorites in Hindu myth.

You know, that’s one of the funniest things about Hinduism to me — it’s like basketball cards. Like, you have favorites? Is religion supposed to be like that? I guess it’s positive. The fact that there’s so many. And I appreciate that there’s female gods too — because there should be.

When Das Racist played at my college a few years ago, you guys were passing out gourds during the show.

Part of it is I come from a temple background, it’s about giving Prasad (food offered to a deity and then eaten by temple worshippers). When we give the fruit and stuff to the crowd, that comes from Hinduism. [Laughs.] For real though, that’s what it is.

FKA twigs, "Glass & Patron"

There is bound to come a day when Tahliah Debrett Barnett fails to impress, but I am happy to assure you that it is not this day, and on present form it seems unlikely to happen anytime soon. Enjoy.

A Flip-Flop Manifesto from a Terribly Wrong and Dangerous Person

A Flip-Flop Manifesto from a Terribly Wrong and Dangerous Person

by Matthew J.X. Malady

People drop things on the Internet and run all the time. So we have to ask. In this edition, writer and editor Elon Green tells us more about the depths of his love for flip-flops.

I feel like I’m finally home. pic.twitter.com/rIwVSiiQgN

— Elon Green (@elongreen) March 16, 2015

Elon! So what happened here?

So: I love flip-flops. I’m not ashamed. To the detriment of my feet, probably, I wear them as often as I can, well into the winter months. I know they can kill me, but in life you pick your battles. They’re like walking on a cloud, and any chill I might suffer is more than offset by the phalangeal freedom.

I’m not promiscuous. I won’t wear just any brand — only Rainbows. (I credit my college roommate Matt, who turned me on to them years ago. He said, correctly, they were the greatest footwear on earth.) They’re not for everyone. Even if you’re used to them, your feet will probably bleed a bit during the first week as you break ’em in. But after that, you’re home free and it’s glorious.

I should note: I frequently take flak for my love of flip-flops. The media establishment has been particularly disdainful — inducements to burn them, attacks on my masculinity, sarcasm, even solidarity with my enemies. But I don’t hold a grudge. People criticize what they don’t understand, and in my heart I know I’m ahead of the curve. Real Americans — those of us in flyover states like Brooklyn — wear such things and the future is ours.

Anyway, I was about due for a new pair. I tend to trade up only when I’ve worn golf ball–sized holes in the sole. Which, since I live in New York, and walk around Manhattan a fair amount, is a pretty gross thing to acknowledge. So I figured, while I was in Sarasota, I ought to scout out fine establishments that sell Rainbows.

OK, flip-flop manifesto time. Have at it.

My fondness for flip-flops is nicely summed up by Dana Stevens, Slate’s eminent film critic. A couple of years ago, Dana wrote the case against them. From her summation:

Because of the ease with which they’re put on and removed — along, perhaps, with their generic ubiquity — flip-flops connote a sort of half-dressed slatternliness, a sense that the wearer has forgotten to do anything at all with his or her body from the ankles down.

To which I say: Yes. Yes! Correct! I mean, I always thought that was the point? If I want to make an effort, I’ll clean my socks and put on a pair of Mephistos! Ease of use is, perhaps, the greatest selling point of the flip-flop.

Not everyone agrees. I had hoped to make my case with a slew of celebrity endorsements, across literature, business, cinema, and the like, but famous people are apparently careful not to be photographed in — or quoted on the record in support of — flip-flops. High profile exceptions are George Clooney and Bill Belichick. That’s a wash.

Better, perhaps, as a favor to those of you who may be persuadable — who are willing to change your mind; to exchange one position for another — here’s a checklist of do’s and don’ts:

• Funeral — don’t

• Job interview — do (this will weed out intolerant employers)

• NYC subway — do (except the L)

• Fancy restaurant — do (unless specifically stipulated)

• Office — don’t (unless you work for Hulu; this is the compromise you make when you stop freelancing)

Lesson learned (if any)?

I can’t imagine what that might be.

Just one more thing.

There are few heroes in the annals of flip-flops — history, after all, is written by the haters. But certainly, when our Hall of Fame is built, the four ladies in the front row — courageous members of the Northwestern University women’s lacrosse team — will get in on the first ballot.

Photo by Drew Stephens

Join the Tell Us More Street Team today! Have you spotted a tweet or some other web thing that you think would make for a perfect Tell Us More column? Get in touch through the Tell Us More tip line.

New York City, March 19, 2015

★★ The sun did what it could, with results more impressive to look at than to be out in. A song and a flutter of feathers stirred in a tubular crossbrace against the blinding sky. A shorn St. Bernard ambled up the block, presumably missing its fur. The humans were in hats and down, the still inescapable requirements in the indigestible cold. The birds sang on in the evening, as if they knew something, or were capable at least of believing it.

A Journey To The Edge Of The Facebook

Facebook’s “Trending” sidebar shows you:

a list of topics and hashtags that have recently spiked in popularity on Facebook. This list is personalized based on a number of factors, including Pages you’ve liked, your location and what’s trending across Facebook.

I rarely interact with links or brands or people on Facebook; my signals, for the purposes of generating a Trending list, are extremely attenuated. Still: stories are selected and served. Which ones? And how many???? I set out on a three-and-a-half-minute journey to find out. THE ANSWERS WILL alksdfjskdfj YOU.