Time Is Flat Coaster on a Very Fancy Bar

A year or two ago, some places in New York — in particular, a surprisingly enjoyable bar decorated like a seventies time machine from an Austin Powers movie, all orange light and black leather and gold highlights, its bathrooms plastered in vintage Playboy covers, with drinks like a fancy Long Island, the Hot Grasshopper, and its namesake Golden Gadillac — revived gross, tacky cocktails from the seventies, give or take, and made them taste good, or at least better. It closed, somewhat sadly. Now, in Portland, we have arrived back at the eighties:

For those unfamiliar with [Jeffrey] Morgenthaler, he’s the man responsible for whipping the bar world into a frenzy over barrel-aged cocktails in 2010 and bottled cocktail sodas a year later. But his most recent contribution, craft versions of “bad” cocktails, has brought back the ’80s, a dark age for drinks. Those who have tasted his Amaretto Sour at Pépé Le Moko, his newest bar in the Ace, know he was the man to do it.

We are so close to reviving pre-Prohibition revival cocktails from the aughts that you can taste it in your Nick and Nora martini coupe.

Photo by Petra de Boevere

Absurdity Banal

“The space, previously home to an artisanal pigs-in-a-blanket shop, has two tables that seat six, and two stools at the slenderest of counters.”

The Attention Brokers

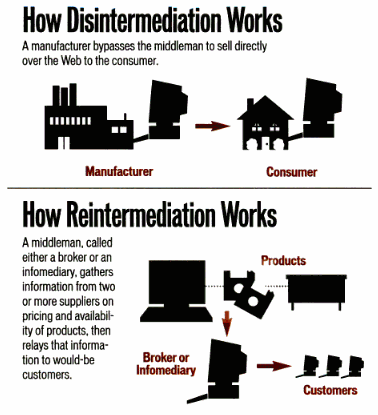

In 1997, a Computerworld column called out a particular stain of internet boosterism. “One of the most recent forecasts for the Web is that it will let companies sell their products directly, bypassing the traditional need for channel support,” David Moschella wrote. “Frequently cited examples include online booksellers, stock traders and travel agencies. Those certainly are interesting examples and powerful examples of the Web’s potential,” he says, “but even a cursory analysis reveals that those innovations have almost nothing to do with disintermediation.”

Internet commerce had arrived, as the prophets foretold! Except it wasn’t Random House or Doubleday selling books, or the authors themselves. It was Amazon. Airlines were selling tickets directly but middleman sites like Expedia, which aggregated tickets into one place, were clearly the future. “At this stage,” he concluded, “we should recognize that competition on the web is mostly about the battle between channels, not their elimination.” Just because two people anywhere in the world can now share information with each other instantly doesn’t mean there isn’t plenty of space in between.

Two years later, in the same magazine, this process — of internet companies destroying middlemen only to eventually become them — was described with another term borrowed from the world of finance:

In 1998, Jack Shafer, then deputy editor of “the on-line magazine” Slate, imagined the media’s odd and accelerated version of this cycle:

Already, electronic commerce mavens are talking about ‘reintermediation,’ in which a new breed of Web middleman will rise to make sense out of the chaos wrought by disintermediation. As the technology of the Web evolves, Internet devices will become as ubiquitous as telephones. Every newspaper will have the potential to break news as fast as a television station. Every television station will have the potential to become a newspaper.

This was a column about the Drudge Report, but replace a few proper nouns and it could almost be a piece about blogging a few years later, or about citizen journalism a few years after that, or about Twitter a few years after that. This framework is useful for describing much bigger things that happened elsewhere online, too. From big web portals to search engines to social media, over the last twenty years the web has been passed, in pieces, between middlemen with either the biggest audiences or a more efficient — or convenient, or useful — form of intermediation. What seems to have changed, mostly, is how fast the hand-offs happen, and how ambitious the middlemen are.

The marginalization of web publishers has been swift. This week seems to be a milestone, at least psychologically, as Facebook, which routes an enormous proportion of the world’s mobile web traffic, prepares to assume the role of funder, distributor and host for news. The Wall Street Journal, writing about Facebook’s plan to host news organizations’ articles (in addition to videos, which are already hosted there) on its own site and app, did so from a notably compliant perspective.

Facebook Inc. is offering to let publishers keep all the revenue from certain advertisements, in a bid to persuade them to distribute content through the social network, according to people familiar with the matter.

Many publishers now post links to their content on Facebook, which has become an important source of online traffic for news sites. But opening those links on a mobile device can be slow and frustrating, taking around eight seconds.

The Facebook initiative, dubbed Instant Articles, is aimed at speeding that process, people familiar with the matter said.

Business Insider laid out the broader situation:

Traditionally, media companies have operated independently and controlled their own destinies. They owned the whole content supply chain, from research to writing to publication to distribution. In the digital era, they built their own web sites, which drew loyal readers (direct traffic), and they sold most of the ads that ran on their sites, keeping 100% of the revenue.

Those days are gone.

Now the fate of publishers increasingly depends on social platforms like Facebook, where billions of people discover news to read and videos to watch. And the social platforms are equally interested in the media business.

“Facebook’s plan,” the article continues, is to “own articles, not media companies.” (All such writing is slightly tense and cautious, sort of like when the Times reports on itself. How are most people going to come to this article about Facebook? Where, a year from now, might they be reading it?)

Facebook’s is a reintermediation by default: the service is such a dominant source of readers — much more so than any other individual website — that it can characterize eight-second load times as a legitimate reason for publishers to grant hosting and distribution of their product to Facebook. From the publisher’s perspective, Facebook went from non-entity to link-sharing site to meaningful source of traffic to one too large not to accommodate, to finally becoming an existential threat. From Facebook’s perspective, this story ran a little less dramatically: it allowed users to add links alongside status updates and photos of friends; it allowed them to be shared, like anything else on the site; it found that these links — which were, at the time, the best way to give Facebook users a way to reference the world outside Facebook — made people use Facebook more. So why should they remain links?

This dissonance explains a lot of the panic welling up across online media right now: To publishers, perhaps blinded by the enormous traffic from Facebook they had come to depend on, and which inflated them to unimagined sizes, this is seen as a bait-and-switch; to Facebook, keeping people on their site and in their app, rather than sending them away multiple times a day, is an obvious product choice — as obvious, to them, as saying an embedded photo is better than a link to a photo, or that an embedded video is better than a link to a video embedded elsewhere. If sharing is taken as approval, Facebook users would probably agree: It’s not Facebook standing between websites and their readers, it’s websites standing between the things they’re trying to read and the feed they want to read them on.

You only have to look back to the middleman service Facebook supplanted to find precedent for this type of argument. From an interview with the creator of Google News, back in 2007:

I think the newspapers should understand and recognise the benefits of what we have done both for them and for the readers. What Google has always tried to do is to make information accessible and useful. We view ourselves as credible, trusted, conscientious intermediary bringing people, who come to us for information, to the right source. We don’t want to serve or own the content but want to direct readers to where the news lives which is various websites of newspapers. We also want to make the whole process very efficient.

It’s extremely unfriendly for me to go to one website for news and then go back and track other sites to get the anti- or a different perspective of the same event, at any given point in time. No reader would bother to do that.

Whether or not Google is (or was) a “conscientious intermediary” is still up for somewhat low-stakes debate. Google News was eventually shut down in Spain after the introduction of rules requiring the company to pay publishers for their content. Now, in an apparent effort to atone (and deflect European antitrust action), the company is gifting over one-hundred and fifty million dollars to European companies awarding “’risk-taking’ in digital journalism.”

This was a comparatively small and specific fight now extending past relevance. The manner in which Google News selected and ranked stories was a constant source of stress for publishers because the site sent significant traffic (I remember, at an old job, the frustration of watching foreign syndications of my stories rank above the originals). Perhaps if Google News kept its influence for a few years longer, and kept growing, it would be asking publishers to host their content for an advertising share (it has, for example, hosted wire stories from services without websites). Maybe it would be making a similar argument: Google News is where everyone gets their stories on their phones, so why should they be links? Why shouldn’t we just host them ourselves?

An internet intermediated by one middleman — an internet that has been effectively consolidated into a single private platform, or into a set of platforms owned by one company — is an internet on which the concept of a publisher is incoherent. At best publishers become euphemistic partners. Otherwise they are reduced to their brands — brands which will then contort to satisfy not just to an array of decentralized commercial requirements, as they always have, often embarrassingly, but to the demands, both explicit and structural, of a single self-interested entity.

It’s useful to imagine alternative histories because the real ones come so quickly. The internet’s earliest software middlemen had the advantage of being able to remove physical inefficiencies — brick and mortar stores, newspapers sent through the mail — and therefore did so deliberately. It was the elimination of an obvious inefficiency that was intended to win people over, and which sometimes did. Disintermediation looks a little different when it’s purely online. A newcomer’s advantage can be defined by ever-smaller differences in time and convenience, or purely by the presence of masses of people. Seamless, for example, can exchange a small and intoxicating convenience for an enormous amount of power; Facebook gets the news because it’s already there. Attention: it makes a strange product.

But the internet is young! It’s full of companies and systems that are, basically, accidents writ large. It’s only from within the web — the loose collection of websites that we think of as important — that its design and contortions seem familiar and right. Taken together, and viewed from the outside, websites, like print publications before them, compose an ugly but functional apparatus crudely organized around commerce and advertising. What they don’t have is the institutional ease and momentum that comes with centralization and size; the digital equivalent of the advantages enjoyed by, say, a Walmart. The other thing they don’t have is your friends.

That you should “go to where your readers are” is fast becoming conventional wisdom among publishers, which is always a sign to start thinking about something else. Google had a profound effect on how people read news on the internet, as well as how it was produced (never forget: Demand Media went public!). But its influence waned, just as Yahoo’s did, just as Aol’s did, just as MSN’s did. Here is a Times story from September 2000, worrying about the state of e-commerce: Are web portals like Yahoo losing sway to sites… with games?

A year ago, the portals were the top source of referrals for 54 percent of all e-commerce sites, the study found, compared with 46 percent of e-commerce sites today. The leading referral site, Yahoo, was the top source of traffic for 30 percent of e-commerce sites last July, but only 18 percent of Internet retailers this summer. The data for the survey was based on 809 sites tracked by Nielsen/NetRatings.

Sean Kaldor, vice president for e-commerce for Nielsen/NetRatings, said retailers were seeking out partnerships with types of Internet companies other than portals. Moreover, the study found a new category of sites is gaining influence in the referral arena: sweepstakes and lottery sites, like Iwon.com, Freelotto.com and Gamesville.com, in part because those sites offer partners an alternative business model.

According to the study, less than 1 percent of referral traffic to e-commerce sites came from sweepstakes or game sites in July 1999, but by July 2000, that figure was nearly 8 percent. Mr. Kaldor said these sites were gaining influence partly because they generally offered partners a ‘’pay per click’’ advertising model.

It’s 2000. Is the future of the commerce beholden to a few sites that exist primarily to test gambling law to its limits? Sure, why the hell not. (Also: “partners,” lol.)

Facebook’s dominance is unprecedented. It is large to the point that it can reasonably claim the ability to reintermediate the entire internet; in countries where the internet is less common, it is doing so in a much more assertive way. But a consequence of Facebook’s reintermediation is that it will create a visible new middleman to eliminate. Its success will illuminate a new structural inefficiency. Step back a few feet (or inches) and re-ask Facebook’s rhetorical questions: Why should people have to wait eight seconds to read an article? Why should they ever have to leave? Grant them, and then take the next logical step: Why should people have to sort through a Facebook feed to get their news?

To someone who makes software, or works at Facebook, this is not a shocking question. It’s a company that knows how quickly things change. Its sudden power over publishers and the news industry is the consequence of a long chain of events the unfolded in an industry that happened to be exploding: the invention of a better touchscreen phone; the widespread adoption of its basic design; the dominance, on mobile networks fast enough to serve the internet but still conspicuously slow, of manually refreshed text-based feeds; Facebook’s fortunate ownership of just such a feed primed with hundreds of millions of users; Facebook’s determined emphasis on getting its app onto phones after stubbornly resisting them long enough that its tardiness had become “a black eye” for the company. The situation web publishers find themselves in is a tertiary consequence of the success of a single company in a historic internet land rush. Facebook is spending billions of dollars to insert itself, preferably early, into the next such chain. Is the future of news celebrity gossip sites posted entirely on Instagram (which Facebook bought in 2012)? Is it people texting each other in apps? Is it… solitary virtual reality pleasure helmets? Again: sure.

The prospect of an internet functionally administrated by a single advertising company has awakened some dormant lobes among the people most responsible for the contours of the commercial internet. The venture capitalists are happily reaping their rewards from a thousands software toll booths, but are beginning to mumble about something bigger:

There’s this hopelessly geeky new technology. It’s too hard to understand and use. How could it ever break the mass market? Yet developers are excited, venture capital is pouring in, and industry players are taking note. Something big might be happening.

That is exactly how the Web looked back in 1994 — right before it exploded. Two decades later, it’s beginning to feel like we might be at a similar liminal moment. Our new contender for the Next Big Thing is the blockchain — the baffling yet alluring innovation that underlies the Bitcoin digital currency.

Encoded in all the confounding hype around Bitcoin, which was covered mostly for its fluctuations in price, is the idea that its public register of all transactions — the blockchain — would disintermediate the internet as we all know it. It’s the internet inoculated against the ills of the internet! It is to the commercial web born in the 90s what that web was to so many non-web businesses before it, if you believe the people who are already investing in it.

Does this mean the next internet, after the big centralization we’re experiencing now, will be less hostile to organizations that wish to exist for reasons beyond the claiming of space and attention? Maybe. But who knows when that will happen? It’s certainly not something a publication can afford to bet on now. What web publishing — and, more important, much of what we refer to as media — can bet on is a coming period of indeterminate length in which the concepts of innovation and compliance will mingle in disorienting ways.

In conclusion, haha, ashkjghasgauosghasugas;gashgk, who knows. Is it time to start talking about a public media for the internet? To start imagining structures within which at least nominally independent media can preserve itself? To do away with the conveniently defined “old ideas” altogether? For the last time: sure. But when wasn’t it?

The CONTENT WARS is an occasional column intended to keep a majority of CONTENT coverage in one easily avoidable place.

Self-organizing robot swarm gifs from this video published by Harvard University

Republic of Hair

by Jordi Gassó

At the end of the workday on a brisk March afternoon, as the miasma of hairspray billowed under fluorescent lamps, Jardin Beauty Salon began to fill with women in smart slacks. Freya Fernández, a thirty-three-year-old administrative assistant, had traveled to the Washington Heights salon from Pelham Bay, like she does every two weeks, to have her hair fixed. After a wash and a deep conditioning, a stylist started to set Fernández’s locks. Some of her natural hair dangled under the rollers. The ringlets, still wet, resembled stretched-out coils, a cascade of thin filaments. Josefina González, a jaunty Dominican hairdresser working on another customer, couldn’t help but call out, “Y ese pajoncito? Eso e’ malo! Eso e’ kinky!” (“What’s with that frizzy mess? That is bad! That is kinky.”)

The salon rattled with cackles. “Don’t you worry, she’ll come out of here with straight hair!“ Eunice Mata, another stylist, said. “After a proper blowout, all hair is good hair.”

Mata, who is from Moca, a small city in northern Dominican Republic known more for its coffee harvests than its beauticians, was juggling two customers. She cradled the hair dryer between her neck and shoulder so she could bundle her client’s hair into thick sheaves. “Dominicans imbue hair with pizzazz,” Mata told me as she pulled on the raven curls of a college student. “We know how to deal with all kinds of hair. We’re complete hairdressers. We cut, we dry, we color, we straighten, we lengthen. No one else can do what we do.”

Jardin (“garden” in Spanish), sits in the beating heart of the Dominican diaspora, on the corner of 173rd Street and a stretch of St. Nicholas Avenue known as Juan Pablo Duarte Boulevard, named in honor of the Dominican Republic’s founding father. The salon offers only a few telltale cues that it is a Dominican beauty shop: broken Spanglish, the rhythm and cadence of gossip, telenovelas on the flatscreen, bachata on the radio, women peddling contraband Victoria’s Secret bras, and a girl wearing a tubi, her hair wrapped around her head and secured with bobby pins.

Customers show up to unwind, sip coffee among compatriots, tell Juana how Beatriz lied on her census form, and eventually procure a Dominican-style blowout, once heralded by Fashionista as “one of NYC’s best-kept beauty secrets.” The process, which costs about twenty-five dollars, is intense but straightforward: A stylist sets the client’s damp hair with rollers, then blasts it under a hood dryer for upwards of thirty minutes. Next, the rollers are removed, and the hair is tenaciously smoothed out with a round brush, hand dryer, and a nimble wrist. The result is hair that looks tamed, yet alive with luster.

Though popular, the blowout is not foolproof: Straightening, whether it involves relaxers, blowouts or hot combs, requires a willingness to endure discomfort and accept the risk of painful mishaps, even under the most professional conditions. Overexposure to high heat can burn hair and cripple its strands. Fernández fell victim to scorched ends at a Dominican salon in the Bronx and had to chop off the damaged hair. But if everything goes as planned, a Dominican blowout will yield a straight and winsome hairstyle. Muertecito, Mata dubs it. Pelo lacio, lank as lank can be.

One of Mata’s clients came to Jardin with her children, who were fidgeting on a couch munching Doritos. I felt for the kid slurping from his juice box trying to make the wait less tedious; not long ago, I found myself killing time in the beauty shops of Santo Domingo. After school, my mother, occasionally with one of my two older sisters, used to drag me to her weekly sessions, where I saw how their hair, despite being naturally straight, got tossed and turned like keratin salad until it looked bouncy, ready-made for a photo shoot. At the time, the commandments of hair care struck me as draconian, an odd choreography involving hair yanking and deafening howls of hot air. But for the women in my life, a visit to the hair salon was a cardinal necessity, an inviolable ritual, which usually meant achieving, or retaining, some semblance of sleek, smooth, straight hair.

Pelo bueno, good hair, is straight hair. Bad hair, or pelo malo, is natural textured hair, the scourge with which you’re born. Proponents of the so-called natural hair movement, in turn, seek to dismantle this distinction by redefining entrenched beauty archetypes, encouraging women to work with what they have, and not with what they wish they had. Their dictums of self-care can sound like foghorns in the Aqua Net mist, but they tend to fall on deaf ears. In the Dominican Republic, where the mixed-race demographic constitutes almost three-quarters of the population, droves of salon clients opt for the Europeanized look — the straight look — like a collective reflex. Dominican expatriates cross the Atlantic with these values in tow, to open up shop in Washington Heights, in the Bronx, in Connecticut. With every blowout, the gospel of pelo bueno turns into something tangible.

During the late nineteen-nineties and early aughts in the Dominican Republic, the commercial for a new brand of hair relaxer, Katiuska, became a local pop-culture sensation. The ad borrowed its catchy riff from Wilfrido Vargas’s popular eighties merengue song, “El Africano” (“The African”), which opens with, “Mami, el negro está rabioso”(“Mommy, the black man is rabid” or “acting furiously.”) The Katiuska jingle replaced “negro”:

Mami, mi pelo está rabioso Mommy, my hair is acting furiously

Quiere pelear conmigo It wants to fight me

Ve comprame Katiuska Go buy me some Katiuska

This adversarial tone, depicting a woman in constant quarrel with her uncouth tresses, has since mellowed out in favor of a more pragmatic approach to taming one’s hair. Dominican salon customers, when prompted, often employ the simple answer, that sporting straight hair is a matter of convenience — that when it comes to hair styling, a woman should adhere to a sort of casual realpolitik. And as seasoned practitioners of their craft, Dominican hairdressers perpetuate this standard of beauty by catering to what their audience wants. Culture dictates the guidelines, and it’s more sensible — and financially savvier — to follow them. “It’s not just us,” González told me. “Everyone wants it straight.” She smirked at me. “If you pay me, I’ll wet my hair so I can show you what’s really bad.”

I can spot the Dominican beauty salon nearest to where I live thanks to the tricolor flag hanging in its front window, even if it weren’t named Dominican Beauty Salon. A modest shop nestled between a Burger King and a tattoo parlor in downtown New Haven, Connecticut, with the exception of a single poster, its walls are primarily lined with stock images of white women flaunting coiffed hairdos. I got to know Damaris Comprés, one of four hairdressers on staff. A spitfire from Santo Domingo with a cheekiness only a veteran could get away with, Comprés has lived in the United States for a third of her life: six years in the Bronx sharpening her skills and ten in New Haven, where “there’s less work and more pay,” she says.

Comprés walked me through the intricacies of hair parlance, a vernacular that can be as insidious and generalized as it is imaginative. There’s the usual baseline — the binary of bueno and malo. More specific types of hair lie in between either end of this spectrum. There’s “medium” hair, which can be wavy but not unmanageable; macho, “like the Mexicans,” jet-black hair that’s both straight and dense; and pimiento, or peppercorn, hair that’s tightly curled up into little pellets, which Comprés leaned in and tried to clarify in an emphatic whisper: “kinky hair!”

Hair is the most transparent of racial signifiers, Comprés told me, more revelatory than a family tree. “The Spanish colonizers got way too mixed up,” she said. “But hair doesn’t lie. We all have a bit of black behind the ears. So you can never be too racist. In Santo Domingo, we are all racists. The black man — el prieto — wants nothing to do with another black man.” She placed her tawny left forearm next to mine, pale as ashes. “Look at your skin!” she said. “You’re truly white. I’m high yellow. Actually, no, I have no color.”

That idiom, “we all have a bit of black behind the ears,” carries baggage. In a book that takes its title from this saying, sociologist Ginetta E.B. Candelario writes, “for much of Dominican history, the national body has been defined as not-black, even as black ancestry has been grudgingly acknowledged.” Instead, she says, Dominicans have perceived themselves as “racially Indian and culturally Hispanic,” the descendants of indigenous people.

Hair, in all its malleable glory, helps Dominicans pick a spot on the color wheel, from canela, cinnamon-brown skin, to trigueña, light like wheat. It’s no different than the way any other human beings have harnessed hair throughout civilization — as expression, as ornament, as proof of membership. This is why salons exist: women tender their money, time and self-image, like votive offerings, to a cultural ideal. “It is not a ridiculous investment,” Candelario told me. “It is actually a very rational thing to do, because the expectation comes from outside.”

If Melphine Evans, a black British Petroleum executive, had flattened her braids by getting a fabulous Dominican blowout, would she have avoided termination, as she alleges, for wearing her natural hair? Would my sister’s evolving career as a lawyer in Santo Domingo suffer if she had pelo malo, and not pelo bueno? Straightening your hair is an act of survival as much as it is a gesture of identity, equal parts censuring and affirming.

In December, Miss Rizos (Miss Curls), a salon in the colonial quarters of Santo Domingo, opened its doors to an intrigued public. They provide services for customers who wish to style and maintain their natural hair without resorting to straightening. It started as a lifestyle blog in 2011 when its founder, Carolina Contreras, who was born in the Dominican Republic, visited her native country after an eighteen-year absence. She grew up in Somerville, Massachusetts, but has lived in Santo Domingo for the past four years. “I wanted to give some love to my poor hair, which had been violated so many times by the burning and tugging from all the straightening, blowouts, dryers, hot combs, tongs and irons,” Caroline writes, in Spanish, on her website. “I began to wonder, why was my hair deemed ‘bad,’ ‘hard to manage,’ and why did stylists have to kill my curls? What did my hair do to deserve its ‘bad’ reputation?” The project hints at the potential for a natural hair movement in the motherland. Perhaps one day, its teachings and hair care treatments will migrate to Dominican hubs abroad, through the minds and hands of hairdressers looking for a new life at places like Jardin, or Grace’s Beauty Salon just a few blocks south.

Late one evening last month, I entered Grace’s, where I received the kind of once-over reserved for health inspectors and traveling salesmen. Mary Díaz, a retiree from Santo Domingo, sat on the styling chair closest to the door. She had a satisfied look on her face, finally able to savor a full Dominican-style blowout after surviving breast cancer. Her feet were bare; her shoes lay strewn on the floor among the hair clippings. Her hair appeared thick and plentiful, straightened and silky. She complimented my hair, lifeless, thinning, and flicked at my gossamer bangs.

“Look at you,” she said, without a trace of irony. “Dios te lo bendiga.” God bless your hair. Straightness is still a gift.

A Poem by Ben Ladouceur

by Mark Bibbins, Editor

Quietism

All hours away from the hearth make us shake

Not all shaking hours occur away from the hearth

The smallest and the only indivisible unit of men is two men

There’s nothing like an ice-cold shower after a spell in the sauna

Antigens springing from each inch of skin as innermost forces evict them

The one you love doesn’t open a door you contain but rather he carefully lifts the door off its hinges and makes a fire from the wood and then he reads by the light of that fire

The inner child’s mission persisting like a garden that has learned to maintain itself

The body in the custody of bone

You only love once

This is because each love negates the previous love

When you say something into the world you give the world a chance to reply with silence

Ben Ladouceur received the Earle Birney Poetry Prize in 2013. He’s had poems in The Walrus and North American Review. Coach House Books recently published his first book, Otter.

You will find more poems here. You may contact the editor at poems@theawl.com.

Landshapes, "Ader"

You know how sometimes people say of something, “It’s not going to change your life or anything, but it’s fine”? Why is the default assumption always that life-changing is good? I mean, I am completely on board with the sentiment that life is essentially terrible, but if there’s anything we should have learned by now it’s that not only can things get worse, that is generally the only direction toward which change moves. Let’s not kid ourselves that change is good. In fact, “not going to change your life” should be something that you run to with open arms and grab hold tight, because if it is something that promises to keep things from getting even the tiniest bit more terrible you want to keep that fucker as close to you as anything you’ve ever embraced so far in your sorry-ass existence. Anyway, Landshapes is a new one to me, and this song is not going to change your life, but it almost certainly won’t make things worse and you might even enjoy it a little bit. So enjoy.

Study: Running Electric Current Through Your Brain Might Not Actually Make You Smarter

This is probably going to come as a shock to you, so you might want to sit down, but — here goes — it turns out hooking your head up to a do-it-yourself brain-electrocuting machine that came from a kit and zapping your mind with electric current could actually make you dumber? Which is a particular problem if you are the kind of person who is hooking your head up to a do-it-yourself brain-electrocuting machine that came from a kit and zapping your mind with electric current, since you surely do not have a lot of IQ points going spare.

Will Russian Space Garbage Solve All Our Problems?

It’s no asteroid, but if a wrecked Russian rocket hurtling toward Earth with no fixed landing point is what it takes to close the books on my existence I am no longer at a point where I would quibble about form.

New York City, May 5, 2015

★★★★ Thin clouds took the most intense solar warmth off the mild morning air. Downtown, midday, the sun was burning through. The new-planted tree where the jimsonweed had been was belatedly putting out tiny leaves. The towering maples by St. Patrick’s Old Cathedral were full-crowned. A dead rat lay pressed flat on new pavement, chopped red spreading out behind its furry back. The iced-coffee taps on the fourth and third floors hissed and spat foamy dregs. Clouds returned to temper the sun and threatened, obliquely, to perhaps do more. Where the open front of a restaurant spilled out onto the sidewalk, sloppy beachwear was showing. Rush hour was gray and seemed quenched even without rain. The rat had been flattened more and blackened till only its tail still identified it.

The 10 Funniest Moments From 'The Last Man on Earth'

by Awl Sponsors

Cr: Jordin Althaus/FOX

This post is brought to you by Hulu. Don’t be left out of the conversation! Be sure to catch up on the episodes of Last Man on Earth and Saturday Night Live.

After just one season, The Last Man on Earth has emerged as one of the funniest and most unique comedies on TV today. Will Forte plays Phil Miller, a self-obsessed oddball who rallies a small community of survivors in post-apocalyptic Tucson, Arizona. After meeting the equally strange Carol (Kristen Schaal) at the end of the first episode, social dynamics in Tucson become increasingly complicated as fellow survivors Melissa (January Jones) and Todd (Mel Rodriguez) join the group.

For those of you who haven’t been keeping up with The Last Man on Earth, we’ve collected some of season one’s most hilarious moments — all of which are available on Hulu.

Phil’s ‘Castaway’ Moments at O’ Rozco’s Bar and Grill | Watch the episode on Hulu

Cr: Jordin Althaus/FOX

When Phil’s loneliness gets out of hand, he finds comfort in a Castaway style brigade of sports balls and inanimate objects.

Anyone Want to Learn How to Milk a Cow? | Watch the episode on Hulu

Cr: Jordin Althaus/FOX

One of the great dynamics of the mid-season episodes is how Phil’s jealousy and vindictiveness toward Todd is held in stark relief to Todd’s good-natured attempts to help the group. This moment from the “cow” episode is a perfect example.

Phil has a thing for Melissa, even though he’s married to Carol. But you can’t stop a guy from dreaming — even if that dream turns into a nightmare.

All Night Long | Watch the episode on Hulu

Cr: Jordin Althaus/FOX

One great recurring joke of the early episodes is Phil’s swimming pool toilet, where he does his “thinking.” Add on top of that a pun on Lionel Richie’s “All Night Long” and you have comedy gold.

Phil Loses It (Again) | Watch the episode on Hulu

Cr: Michael Becker/FOX

Phil barely holds on to his sanity as Carol continues to infringe on his way of life. Here is he flipping out (again) on a routine shopping trip.

Carol Passive-Aggressively Lashes Out | Watch the episode on Hulu

Cr: Jordin Althaus/FOX

After Phil lies to Erica and Gail about Carol’s death, Todd and Melissa stop by to try and comfort her. But Carol refuses to let the “pity party” continue.

Phil’s Dream Sequence, “She Drives Me Crazy” | Watch the episode on Hulu

Phil has a thing for Melissa, even though he’s married to Carol. But you can’t stop a guy from dreaming — even if that dream turns into a nightmare.

Raisin Meatballs | Watch the episode on Hulu

As it turns out, fresh food is scarce in post-apocalyptic Tucson — meat in particular. It’s oddly touching when Carol tries (and fails) to create a meat-like ball out of raisins. “They look like meatballs but the taste is very different.”

Carol “Touches Up” Phil’s Monet | Watch the episode on Hulu

In a post-apocalyptic world, you can finally have all the things you never had before the End Times. In this scene, Carol “touches up” Phil’s prized Monet paintings he’s pilfered from legit museums.

Carol’s Jealous Streak | Watch the episode on Hulu

One of the reasons The Last Man on Earth is so fun is because it showcases humanity’s basest impulses. Like this scene, when Carol sees Melissa and Todd’s budding romance. She can barely contain her jealousy.

Phil Eats Toilet Paper to Survive

Cr: Ray Mickshaw/FOX

After being exiled by the other Phil Miller, Phil “Tandy” Miller locks himself in his room for three days — surviving on nothing but toilet paper. “You are a toilet paper corn dog,” Phil mutters to a roll as he takes a bite.

If looking for more awesome comedy, look out for the Season 40 finale of Saturday Night Live — with host Louis CK — coming up May 16. (Tip: If you’re behind on SNL, catch up on Hulu!)

This post is brought to you by Hulu. Don’t be left out of the conversation! Be sure to catch up on the episodes of Last Man on Earth and Saturday Night Live.