Meet Hamasaku's Eccentric, Self-Made Executive Sushi Chef

by Awl Sponsors

The Sushi Chef is a new series about the personalities behind the incredible fish found in New York and LA’s best sushi restaurants. While slicing raw fish may seem simple, we find that in the hands of certain chefs, sushi transcends its identity as just a type of cuisine and truly becomes an art.

Yoya Takahashi, the vocal and eccentric executive sushi chef at Hamasaku in West Los Angeles, never set out to be one of the most influential sushi chefs on the West coast. He originally came to the United States with the dream of following in his grandfather’s footsteps and becoming an actor. Now, after 14 years making sushi, this is the longest time Takahashi has spent doing, well, anything. “Yes! Exactly,” he says, “sushi changed my life.”

When he first came to LA, Takahashi was broke and didn’t speak any English. Needing money, he took a job as a server at a sushi restaurant. Noticing he was a “big guy with a loud voice,” his boss asked if he wanted to start preparing sushi for their customers. “Being a sushi chef is kind of like being a stage actor,” Takahashi says.

Now Takahashi puts all of his creative energy into experimenting with his sushi dishes. He uses everything from shark hearts (which he served for valentines day) to fish sperm sushi. His relentless need to innovate has helped turn Hamasaku into more than just a power lunch spot in LA — it’s also a destination for sushi connoisseurs.

Takahashi finds the greatest pleasure in converting Americans who previously didn’t eat sushi into sushi lovers. He’ll strike up a conversation with his audience from behind the sushi bar to figure out exactly what his audience will like best. For Takahashi, learning about sushi is learning about Japanese culture and history. “That’s why I totally enjoy Los Angeles people getting started to eat sushi.”

Cambridge, Mass., to New York City, May 31, 2015

★★★★ Intermittent fine showers wetted down the deck and then allowed dry patches to form before wetting it down again. A cardinal landed on the side fence and a robin landed on the next fence over. Pale tree parts blew down at an angle. At car-loading time, new drops made big dots on the driveway. The showers came on harder, in blinding squalls on the Mass Pike and on down I-84, punctuated by long pauses that made it seem the rain was spent and inspired cars to speed up on the now manageable pavement. The ordinary rolling tree-softened hills of Connecticut were veiled in layered mists and slashed with shocking greens like a mystical Chinese landscape painting. With each new fold of mist came sudden flinching brake lights and then the waters slamming into the car again. The roadway smoked; rain hammered down on the metal of the slow-moving roof. The most panicked drivers put on their flashers, even in the left lane. The darkness was like nightfall. Ghastly twisted black shapes loomed above the hilltops. Lightning struck with a percussive, nearby snap. A motorcycle, speeding greedily down the center line between crawling cars, came out of the gray mists from the rear to find a black Tacoma changing lanes — the cyclist, with no hope of stopping, veered and threw down a foot and just barely angled along the flank of the pickup truck to reach the inner shoulder alive. Everything continued: the gray, the waves of rain, the silver wind-whipped foliage. A broken chunk of tree, ends new-sawn, lay on the bank beside the parkway, the turf behind it showing a deep fresh black gouge. The road reached the city, and an ordinary city rain. Lightning forked in the distance above an ugly pink apartment building. People were out lugging grocery bags or slogging along, under umbrellas or in ponchos or just drenched in their clothes, caught somehow unawares.

According to Pew

Pew has a new report out called “Millennials & Political News.” An introduction:

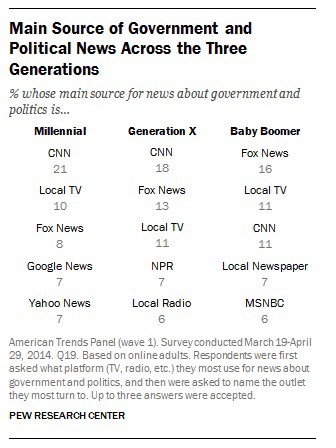

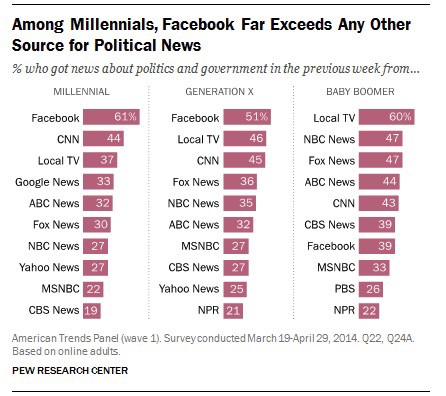

Among Millennials, Facebook is far and away the most common source for news about government and politics. When asked whether they got political and government news from each of 42 sources in the previous week (36 specific news outlets, local TV generally and 5 social networking sites), about six-in-ten Web-using Millennials (61%) reported getting political news on Facebook. That is 17 points higher than the next most consumed source for Millennials (CNN at 44%).

And some data:

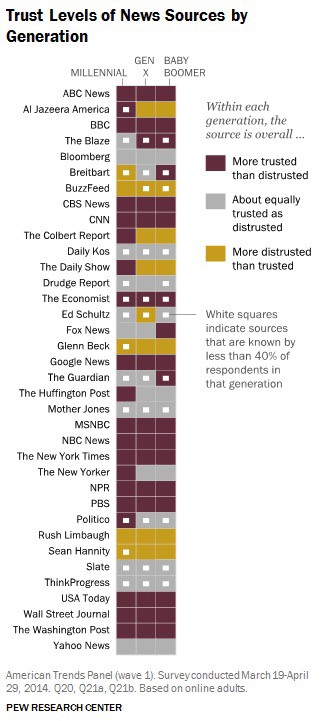

According to Pew, “Local TV,” which includes hundreds of television channels, many affiliated with major networks, is a news source that is comparable to “CNN,” a cable news channel (and website and YouTube channel and Facebook page and Twitter page). It is also comparable to “Google News,” which itself does not produce news, but which posts links to both CNN and “Local TV” websites, as well as to “Local Newspapers,” which are also included in this list.

According to Pew, MSNBC, a channel and website, is directly comparable to Ed Schultz, who has a show that airs on MSNBC, and to The Daily Show, which airs on Comedy Central, a channel that is not included on this list. The Drudge Report, a list of links to other items on this list, is comparable to NPR, a radio non-profit that syndicates content to hundreds of radio stations as well as the internet, through its app and partner station apps.

Also according to Pew, these generations — Millennial, Gen X, Boomer — are not a cynical marketing theology that should be rejected outright, but a necessary shorthand — longhand? — for groups of people born between certain years.

According to Pew, this is one way its data was gathered.

According to Pew, Facebook, on which users post links and media from other places, is also a “source” of political news.

Therefore, according to Pew, “Social Media” could be… “the Local TV for the Next Generation.” According to Pew.

"Here's How Long It's Been Since America Elected A Bachelor President"

Here is a post from conservative viral Facebook plugin IJReview:

Lindsey Graham (R-SC) is announcing his candidacy for the United States Presidency today. In addition to being the first person to announce out of South Carolina since Stephen Colbert, he holds one other rather unique distinction.America hasn’t elected a single President to the White House since 1885.

Welcome to 2016, when you can’t even tell which dogs the whistles are for!

The Errors of Our Ways

by Lidia Jean Kott

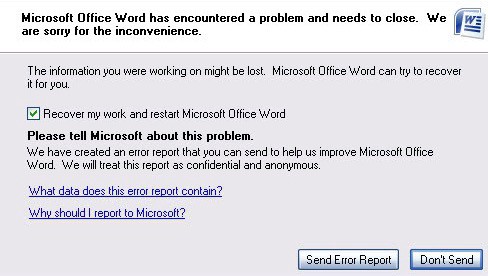

One evening this fall, my Microsoft Word crashed. I didn’t send my error report, but afterwards I kept wondering about what would have happened if I had. Could there be someone, somewhere, blurry-eyed, scrolling through thousands of crashes a day? It seemed unlikely. I contacted a friend who works in software development to find out. He sent me a link to an Internet forum with a thread on the topic. The comments were disappointingly vague, but one of the commentators seemed knowledgeable. I tracked him down and called him. He told me to talk to Kirk Glerum — the “father of Windows Error Reporting.”

When I first reached Glerum, a semi-retired technology consultant, over Skype, he was in the study of his house in Redmond, Washington, and the sound on his computer wasn’t working. We could see each other, but not hear each other. I offered to hang up and try again, but Glerum didn’t notice my message. He was too busy clicking. He looked a bit like a space ship commander, in oversize black headphones and a polo shirt buttoned almost all the way to the top. Two dark cats walked across the screen. Glerum kept his eyes narrowed and tapped his lower lip. Glerum’s love for computers began when he was in high school in the ’70s in Beaverton, Oregon. He saw an electric calculator for the first time and found it fascinating. “You could tell the darn thing what to do, that’s the beauty of programming,” he told me. “I mean, half the time it doesn’t work. And that’s how we got to [Error Reporting].”

Windows Error Reporting was introduced with Windows XP in 2001. It’s “the one innovation that changed software development the most in the past 20 years — for the best,” says James Larus, a computer science professor at a university in Switzerland and a former Microsoft employee himself. The feature opened up one of the first direct lines of communication between users and developers. Before, the only way to reach Microsoft was through waiting on hold with call centers. Now, prompts to send crash reports over the Internet are standard. Apple uses error reporting, and so do Google, Adobe, and many start-ups. Most error reporting, at the initial level, is opt-out, meaning that reports get sent automatically, unless you turn off the feature. We’re constantly sending off reports, often without even knowing what we’re sending. Microsoft alone receives 16 million crash reports in an average four-month window, according to a 2014 study by the cyber security firm Websense.

But it wasn’t always clear that error reporting would catch on. Eric LeVine, the former Group Program Manager for Windows Error Reporting, first heard Glerum make his pitch at a lunch table at Microsoft’s headquarters in Redmond. This was in the late ’90s when Microsoft had a terrible reputation for being glitch-y and unreliable. But LeVine was unconvinced that error reporting could solve the company’s problems. “That’s insane,” LeVine remembers thinking. “We would crash all the servers in the world.” There was not much precedent for crowdsourcing information or sorting through it in any useful way. The term “big data” had not yet even entered common parlance. “In that time, [Windows Error Reporting] was totally novel and audacious,” LeVine says. Glerum already had a reputation for being “kind of way out there.” Once for Halloween, he had shaved his head and glued computer keys to it, which may have also contributed to LeVine’s skepticism.

But error reporting turned out to work better than anyone around that lunch table could have predicted. LeVine says that in its first three years the feature wiped out ninety-five percent of crashes in Office Products. Here’s how it works. After a program crashes, the operating system gathers information such as the name of the application that crashed as well the names of all the other applications that were running at the time. The operating system might also swoop up some personal information, like the name of the document you were working on. Microsoft promises to keep everything confidential. Still, a former employee, who spoke anonymously due to the rules of the company’s non-disclosure agreement, says that if your computer crashes while you’re working on a particularly sensitively titled document, you might choose not to send that report.

The report is then sent to Microsoft’s servers where it’s sorted according to Pareto’s Principle. Vilfredo Pareto was a nineteenth — century Italian economist and sociologist, with a long white beard in his Encyclopedia Britannica picture. His principle, which was based on studying land distribution in Italy, states that about eighty percent of effects come from about twenty percent of causes. At Microsoft, this means that all like crashes — for instance two crashes that occurred in the same location — are grouped together and developers first look at the most common ones, based on the conceit that if they prioritize those, they’ll end up also fixing the majority of problems. LeVine remembers fondly the first problem fixed with Windows Error Reporting: a glitch with an Adobe add-on to Microsoft Word. The add-on was mean to convert files to PDF’s, but it also inadvertently caused Word to always crash right before closing. The solution to that problem marked the beginning of a new era.

Nobody at Microsoft was available to comment about the role that error reporting currently plays in the company. But I spoke to a few former employees about what it was like when they worked there. One of them, who left Microsoft in 2011, says that developers received an email with lists of the top ten crashes on programs they had worked on — an email he calls “the wall of shame.” “You wouldn’t do anything until you fixed your ‘wall of shame’,” he says. An employee who left last year explained that each crash has its own form that developers studied in order to fix it. The form has hundreds of different text fields that include information about where the crash happened, how many times it happened, and what its impact was. There’s also a space for notes from developers about what they’ve already tried or their thoughts about what the issue might be. The former employee puts it like this, “First priority, complete your crashes. At this point, it’s like of course we do it this way. And it used to be radical.”

Error reports actually contain a fair amount of information, and are constantly flying through cyberspace, which made them targets for the NSA. In December 2013, Der Spiegel published a story about how the NSA can intercept Microsoft’s error reports and mine them for clues on how to hack into people’s computers. In an internal presentation, NSA agents replaced the text in Microsoft’s error message asking if you’d like to send a report with their own reading: “This information may be intercepted … to gather detailed information and better exploit your machine.” Alexander Watson, the CEO of the cyber security firm harvest.ai, was in Germany at a technology conference around the time the Der Spiegel story came out. He was surprised by how little even the conference attendees knew about what information error reports contain. “People should know what’s getting sent,” Watson says. “If an attacker were to compromise that they would have a blueprint of how to attack you.”

Yet after the Der Spiegel story came out, Glerum says that he and a couple other members of the original error reporting team all just rolled their eyes. To them, it seemed like a lot of hubbub for no reason. Glerum holds that error reports are too lightweight to contain any information that would be of any practical use to hackers or spies. “I’d love to have lunch with the guys from the NSA who used my stuff,” Glerum says, his tone carrying just the slightest whiff of a challenge.

Brendan Conlon, the CEO of the cyber security firm VAHNA, served as the NSA’s Deputy Chief of Integrated Cyber Operations from 2011 to 2013. Conlon isn’t allowed to talk about how the NSA uses error reports. But according to Der Spiegel, the reports reveal information about the security holes in a targeted person’s computer, which means in theory the agency could generate malware to exploit those weaknesses. Though Conlon won’t draw on his experiences at the agency, he can discuss error reports as a cyber security analyst. “You are sending out information that could be used in a bad way,” he tells me, over the phone. “But you must think about that every time you’re on the Internet. Twitter, Snapchat, your personal information is out there.” Conlon still sends his error reports, though because he says they help improve software. To him, the risk is minimal and worth it. “You’re helping out the rest of the world,” he says.

There is something emotional about error reporting. That’s no accident. Glerum says that when he started at Microsoft, after a program crashed, a dialogue box would appear “that looked like it was admonishing you for something.” It would say, for example, “This program will be terminated,” Glerum recalls, his voice turning deep and robotic. Glerum and his team rewrote the text to make it sound more human. “We wanted people to submit their reports,” he says. “We were desperate to make it sound reasonable.” One of the main changes they made was to add the line “We’re sorry.” But some say the current dialogue box opens up the company to criticism. “The way that Microsoft designed the program, you think ‘Ah Windows, you crashed again.’ Why would you design it that way?” asks a former employee. He points out that on a Windows computer the same apologetic popup appears, even if the program that crashed wasn’t made by Microsoft, making the company look responsible for flaws that aren’t their fault. And most people, after experiencing a crash, don’t feel too forgiving. The comedian Natalie Tran posted an animated video on YouTube in 2010 where she imagines the guy who receives error reports printing them out and eating the paper.

But for Eric LeVine, the former Windows Error Reporting Program Manager, error messages bring up more positive associations. Retired from Microsoft, he lives in Bern, Switzerland where he runs CellarTracker, one of the largest wine websites in the world. LeVine says the website would never have existed if it weren’t for Windows Error Reporting. About six months after he starting working on the project, LeVine took a bicycle wine tour through Tuscany. After LeVine returned, he started a spreadsheet to keep track of his wine tasting notes, and the best times to drink the wines in his cellar. He passed the spreadsheet around the office and his co-workers added their notes too. Eventually, the spreadsheet became a website. Windows Error Reporting served as the model, he says. “The idea really came out of that time — and how to structure things you wouldn’t think you’d be able to structure.”

I can’t say that I always send my own reports now. I often forget, or just feel too impatient. But now I know that a developer might actually read my error reports — when I send them. In the old days, Glerum went through all of the reports himself. At certain points, it took him 20 hours to process one day’s worth of data. “I was a total cowboy, staring at my laptop,” he says. I find it reassuring to think of him, in his oversize headphones and buttoned-up polo, working late at night on a dialogue box that would one day pop up on nearly all of our screens. It turns out that our reports are sorted. And to me, the world seems like a slightly less chaotic, more organized, place because of it.

Gif via PC Pitstop

Smoking Advice

Here is some advice on how to quit smoking, but be warned that the first item on the list is “Start smoking,” so if you haven’t gotten that far yet you should probably just bookmark it and come back to it once you’ve really developed your habit.

Ta-ku, "Long Time No See"

Some incredibly gentle R&B; for a gentle re-entry into the week, or at least the ear-wise impression of one.

I'm Graduating High School and I Want to Be a Journalist but Everyone Says I'm Nuts!

by The Concessionist

The Concessionist gives advice like… once a month maybe? Whatever. I’m busy. Trouble? Write today.

Hello,

For a long while now, I’ve thought I wanted to major in journalism. It’s been something I could see as a passion, or a career. But lately, when I’ve been in bed late at night, I worry.

I graduate high school in a week, and although I’ve already had an internship at a newspaper, mostly all of the editors and reporters took me aside to voice what they saw as a way to save me from boarding a sinking ship.

“Don’t major in this,” they told me. “Please go to law school.”

Now, I know that a newspaper is probably the easiest place to find a jaded journalist, and a depressed and underpaid one at that, but if these people are telling me the truth then what do I have to look forward to? I’m a naive high school kid, and I know nothing about the world yet. This is an undeniable fact. I can feel the strange, strange way that this pulls me in while all the while I know it’s not a smart career choice. The job market is down, and the whole industry is over saturated. On one side, I see myself taking a risk and succeeding — perhaps not wildly, but at least comfortably. On the other side of my mind, however, I see a dissatisfied store clerk, fuming at my 2015 self for not taking accounting by the hand and running with it. This is my dilemma. I do not want to be sixty years old and looking back, thinking of what might have been had I been brave enough to take a chance. I also, however, do not want to be an embittered old woman, her accolades nothing more than her college publications. The industry is changing, and I’m afraid.

Sincerely,

[redacted]

Hello young person,

Here are just a few things I think you need to know.

1. You do not need to know what your college major is going to be now. Or maybe ever. You truly don’t! You’re going to college! You should be excited about going to college and be busy planning an experience for yourself. Do you want to be doing outdoors things? Do you want to be deep in a library? Do you want to be taking big lectures, or studying with smaller groups? Do you want to be painting and taking lots of drugs and arguing? What does your dream college look like to you? Let’s worry about that now. And also focus on GETTING OUT OF HIGH SCHOOL and starting a whole new life! You’re up all night fretting when you should be celebrating.

2. If you hate your college, you can leave it for another one. Colleges are all very different and they are not one size fits all! But even if you hate your college, you can also start your life over at the same college. Most colleges are big enough that they contain multiple existences. If it’s dreadful, or you make a bunch of mistakes in your first year, switch it up: apply for overseas programs, switch majors, change your focus, change where you live, change your diet, change your name even. My point is: you can mix up your path at any time. That’s also true in the real world. And if you really hate it, or find something better to do, drop out! You can live without college, though it’s rough, lemme tell ya.

3. You don’t have to be a journalist first, or for forever. Many people go through their entire lives without a passion to do something in particular for a living. Isn’t that funny to think about? But it’s true — they may like certain things or be good at a set of skills for instance, but they don’t have a drive to like “be a litigator” or “write romance novels” or whatever. But you do have a passion. If you want to work on the college paper, great! If you want to intern in the summers or look for fellowships in journalism, awesome. You should!

But also you’ll learn a lot about your interests in the next four years — and they might surprise you.

I don’t in general have a lot of regrets, because regrets are for losers, but I do wish that I’d accumulated a more sophisticated sense of privilege early on. I would have learned so much more about the world! Some young people are taught that the world is there for the taking. It is our job to teach that to every young person, not just the ones who went to private schools and private colleges. Entry level jobs in sales, business, real estate and even some levels of finance have little barrier to entry, it turns out, even though this is where the 1% hide all their children. The fields are only packed with muttonheads and pearl-clutchers from Trinity-Pawling and Loomis Chaffee because they are told how to get there. The rest of us just need to be informed. The point being, you can take a thousand paths to performing journalism, and being literate in the ways of the world is actually a much better path than being literate in journalism. Journalism is easy to learn. The world is much harder.

For instance, have you ever read journalists writing about the media business itself? For the most part, they have literally no idea what they’re talking about. They don’t know how marketing or circulation or advertising sales work; they aren’t familiar with the technology of their own publications; they certainly don’t understand the financing and ownership of their own publications. When their publications or publications they admire fold or are sold or are “sold,” they tend to print the story they are told rather than the story that is obviously true. This happens even at the highest levels; you can see media reporters at the New York Times relaying concepts or ideas or narratives that they don’t actually understand or possibly, if they took a breath, even believe.

Should this happen to you? Say no! And start now! Major in art. Major in finance. Major in chemistry! Major in engineering science! Major in accounting! Major in Russian! Major in statistics! Major in African-American studies! Literally any of those will serve you better in the world — and in journalism — than the undergraduate study of journalism.

By the time you graduate college in four years, we will already be on the other side of the current insanity in the industry and into a new flurry of insanity. The Great Consolidation will mostly have occurred. Henry Blodget will have triumphantly returned to Wall Street to ring the opening bell; Vox Holding Industries LLC will have long IPO’d; BuzzFeed Sony Paramount will still be hiring journalists out on the east coast to cover their own films. Disney’s FusionLand will be hiring catering specialists. Maybe Barry Diller’s New York Post and Times and News will be beefing up.

Will this web page even exist in four years to be mocked? Probably not. Perhaps it’ll be archived on Awl.Vice.Kinja.com somewhere, or it’ll be deep in the old archives of FaceMedium. It doesn’t matter. All things turn to dust. But not you, not yet! Whatever weird landscape you have to face then will be just as surreal as this one. You actually can’t worry about it now; it’s literally unimaginable. Ha ha, you’ll have so much to worry about in four years! But for now, follow your dreams, try not to tweet too much, and go learn something that no one else knows.

The Concessionist is an adult human in New York City who is somewhat worn down and willing to make a good number of sacrifices for a peaceful life. Is it decision fatigue? Or just ennui? That’s probably a question for a psychiatrist. Anything else, ask me. I agree to keep your identity between us unless like an emergency exists. Photo of cheerleaders with ennui excerpted from this photo by Ed Uthman.

• Should Straight White Men Be Ashamed of Themselves?

• My Ladyfriend Hates My Lady Friend

• I Hate Myself Because I Don’t Work For BuzzFeed

• In Praise of Getting Back Together with the Dude who Dumped You

• How to Make Your Girlfriend Like You (Again)

New York City, May 28, 2015

★★★★ The middle distance was surprisingly murky. Clouds kept the heat off the soggy-aired morning for a while. Then things brightened and warmed up into a pleasantly blinding, pleasantly crushing heat. The stillness was good to be out in, inert on a padded roof chair, the buildings blue-faded versions of themselves. The scattered blue was so intense that the shadows on red chairs were purple. The mobile phone was almost too dim to read and almost too hot to hold, and both facts seemed worth attending to. Another commute under menacing skies led to a view of a peaceable blue-and-white-streaked west and to a wavering shadow on the kitchen wall where full sun passed through the heat of a burner. The blue and white streaks turned blue and pink, sending a pink glow into the apartment and pinkening the scenery outside.