A Poem by Noah Falck

by Mark Bibbins, Editor

Poem Excluding Babysitter

As we drive past the cemetery we hold

our breath for several minutes. Our

faces grow obscene floral patterns. In

our breathlessness, our skulls empty

themselves. Trees in winter. Our

children in the backseat became the

moral of the story — startling us with

propaganda, with sudden musicality,

with their small, loose teeth.

Noah Falck is the author of Snowmen Losing Weight, and several chapbooks including Celebrity Dream Poems and Life as a Crossword Puzzle. He works as education director at Just Buffalo Literary Center and co-curates the Silo City Reading Series in an abandoned grain silo along the Buffalo River.

You will find more poems here. You may contact the editor at poems@theawl.com.

How Esquire Engineered the Modern Bachelor

by Manisha Aggarwal-Schifellite

In the fall of 1949, the editors of Esquire magazine published Esquire’s Handbook for Hosts, billed as the “all-time, all-knowing, all-inclusive, all-man reference book on ‘Eat, Drink, and Be Merry.’” The Handbook included recipes, drink ideas, games, decorating tips, and general etiquette for “every male, be he the lad in the fifteen-room penthouse, or the guy in the glorified piano crate below street level.” It was released at the outset of the Cold War; the baby boomer period of the late forties and fifties ushered in a new era of suburban development and a return to an idyllic family structure that the government promoted as socially and economically necessary for defeating communism. Women were encouraged to leave the jobs they had held throughout the war, and men were encouraged to take on the breadwinner role and aggressively retain the masculinity of wartime heroism.

One of the central issues of Esquire’s content during and after the war was that masculinity was constantly under threat, mostly from women and the increasingly stratified corporate work system. At the same time as domesticity was supposedly squeezing men into submission, so too was corporate work culture. Books like Philip Wylie’s Generation of Vipers (1942), David Riesman’s The Lonely Crowd (1950), Sloan Wilson’s The Man in the Gray Flannel Suit (1955), and William Whyte’s The Organization Man (1956) lamented the end of traditional masculinity and the feminization of both work and home for the man who used to have total control over his life.

Wylie claimed that overprotective mothers made their sons soft (he called it “momism”), a problem that would ultimately result in a communist takeover of the United States. In The Lonely Crowd, Riesman said that work culture was transforming men from “inner-directed” people who were self-sufficient and of good moral character to “outer-directed” people who were obsessed with their appearance and a desire to fit in. The protagonist of Wilson’s novel, Tom Rath, returns from war and loses his sense of self in a monotonous job that pays for his wife’s dream home in the suburbs. Whyte claimed that bureaucracy had ruined the entrepreneurial spirit of American men. Ultimately, these cultural critics decided that if men couldn’t control their work or their home lives, they would become emasculated sissies and the nation would fall apart.

It was this loss of control that was so nerve-wracking for white men during the Cold War, and it was Esquire’s — and, starting in 1953, Playboy’s — job to help guide readers through the uncharted territory of second-wave feminism, civil rights, and communism. To do this, Esquire turned to a character that, historically, had total control over his own life: the bachelor. The magazine’s November 1949 editorial claimed that the book’s readers would become less dependent on “the little woman” (presumably Mrs. Esquire) who had been responsible for the household until this point. In this period of perceived crisis, how did Esquire convince their readers that it was acceptable (and necessary) for men to be bachelors, and for those bachelors to care about their appearance, their home décor, and their cooking skills?

The social connotations of being a single man in America have changed a lot over the past three centuries. According to John Gilbert McCurdy in Citizen Bachelors: Manhood and the Creation of the United States, the word “bachelor” was first enshrined into American law in 1703, as part of a New York City ordinance taxing unmarried men at the same rate as married men for a new city project. This ordinance was one in a series of laws that determined that single men were capable of financial contribution to the state, even if they did not own property. After the Revolutionary War, American leaders were intent on differentiating the new nation from their former British masters, and redefining manhood became part of that change. John Adams saw British bachelors as “effeminate,” yet touted American bachelors as virtuous and able to resist temptations of vice. McCurdy writes that once bachelors were seen as equal to married men under the law (a common regulation by 1800), the image of the bachelor became associated with masculine independence and autonomy, even as he remained a subject of suspicion when it came to morality; the common sentiment at the time, according to McCurdy, was that “a bachelor may make all the wrong decisions and devote himself to a life of luxury, but this was the bachelor’s prerogative, which few Americans felt any compunction to hinder.”

The bachelor remained a fixture of public life and popular culture throughout the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. One of the most important developments in bachelor culture was the emergence of sporting-male societies in the early eighteen hundreds, which celebrated male friendship, exclusive clubs, and vigorous exercise. In American sporting-male culture, middle- and working-class men spent time together in gambling houses, brothels, and billiard clubs; their independence and autonomy were held up as markers of masculinity among their peers — having a wife and children was a trap to be avoided for any man who valued his freedom. Some sporting-male bachelors had left their families in other countries or in other parts of the country, resulting in less surveillance from relatives and communities. And even though many bachelors held down steady white-collar jobs and lived with family members, many who had blue-collar jobs lived alone in boarding or rooming houses (some of these houses were exclusively held for bachelors, and became clubhouses as well as lodging). One example of this celebration of homosocial (and sometimes homosexual) bachelor subculture is the -essay collection by writer Donald Mitchell, called Reveries of a Bachelor, published in 1850:

Can a man stake his bachelor respectability, his independence, and comfort, upon the die of absorbing, unchanging, relentless marriage, without trembling at the venture? Shall a man who has been free to chase his fancies over the wide-world, without let or hindrance, shut himself up to marriage-ship, within four walls called Home, that are to claim him, his time, his trouble, and his tears, thenceforward forever more, without doubts thick, and thick-coming as Smoke?

By 1900, the image of the bachelor had become firmly intertwined with the image of the rugged American man — a Marlboro Man-type who embodied a frontier spirit of self-reliance and separation from workplace hierarchies, salaried jobs, and the demands of marriage and family life. Around this time, a growing parenting movement encouraged middle-class men to be more involved in their children’s lives, to a point; it was thought that fathers could provide necessary moral and career knowledge to their sons. So while more middle-class men engaged in childrearing activities that kept them closer to home, popular literature, film, and advertising celebrated the lone wolf persona of the bachelor in his many forms: hardboiled detective, rugged adventurer, artist, or writer. In all of these situations, it was the detachment of the man from his environment, along with his rejection of class structure that made him an appealing character to readers and viewers.

In the twenties and thirties, the bachelor rose to prominence in pop culture as a symbol of a hedonistic life that some men were leading, and others wished they could. Unmarried or married, George Chauncey writes in “Trade, Wolves, and the Boundaries of Normal Manhood,” the bachelor subcultures of nineteen-twenties New York, particularly for working-class immigrants, were home to men who “forged an alternative definition of manliness that was predicated on a rejection of family obligations.” This rejection was often based on immigration or migration circumstances, but in other cases, it was a choice to be a bachelor, or at least to pretend to be one to avoid responsibility or to meet other men.

This wishful thinking fuelled Esquire’s approach to the bachelor lifestyle. Esquire’s reign as the king of American men’s magazines began in 1933, when its founder and first editor, Arnold Gingrich, envisioned a magazine made for men who enjoyed luxury in all its forms. Before Esquire, magazines were either general interest publications like the Saturday Evening Post, which assumed a mostly male readership, or were aimed at women, like The Ladies’ Home Journal. According to Leslie Newton’s article, “Picturing Smartness: Cartoons in the New Yorker, Vanity Fair and Esquire in the Age of Cultural Celebrities,” Gingrich’s first editorial declared that Esquire was the magazine designed for “the cream of that great middle class between nobility and the peasantry. In a market sense . . . Esquire means simply Mister — the man of the middle class.” This ideal reader was sophisticated, rich, and interested in the finer things in life. He also did what he wanted — freedom from obligation was crucial to the Esquire brand, and that obligation extended to freedom from women. Instead of highlighting the realities of single life, Esquire‘s portrayal of bachelorhood was based on looking and acting the part of the swinging ladies’ man, even though most of the magazine’s readers were married. Esquire’s idealized postwar bachelor had no obligations outside of his own desire for women and luxury products (often considered one in the same). He bought his own clothes, drove his own car, and took solo vacations to exotic places. The bachelor became a symbol of postwar consumerism and hedonism, and as a result, became a symbol of freedom for white American men looking for a way to feel important again. Because Esquire relied on corporate advertising to continue existing, overthrowing corporate hierarchy and stratification didn’t factor into their discussions of masculine rejuvenation. In the Handbook, women were presented as an obstacle to men’s success at entertaining, which reinforced the theory that women were ultimately responsible for men’s inability to control their lives.

The ideal life of the bachelor may have been one of absolute freedom, but the instructional elements of the Handbook made it clear that there was a right way to live a bachelor life, and it involved buying the right clothes, décor, food, and drinks. By lumping bachelors and married men together, the book’s editors implied that one could be a bachelor in every way but semantics, if he could follow the rules. Esquire encouraged both groups to consider themselves part of a new revolution in bachelorhood that didn’t actually require a man to be single, but to act like he was one by purchasing the luxury clothes, food, and other items necessary to convey a hedonistic lifestyle. In the “Be Merry” section of the Handbook, the editors allude to this shift, writing: “All of the delicious shudders and social taboos have been eliminated from the once daring adventure of ‘visiting a bachelor in his rooms,’ at least so far as adults are concerned.”

In Playboys in Paradise: Masculinity, Youth, and Leisure-style in Modern America, Bill Osgerby highlights the importance of the home in asserting new bachelorhood, even if the men who participated were actually married. The “bachelor pad” was a touchstone of fifties and sixties popular culture, from blueprint designs of “Playboy’s Penthouse” to the lavish bachelor pads in movies like Some Like it Hot and Pillow Talk. (Osgerby points out that Rock Hudson was held up as a symbol of sixties male hedonism in part due to his film roles as a “swinging” bachelor.) The Handbook hints at this development a decade earlier with a note for bachelors hoping to entertain:

Granting that you are a bachelor and not a hermit, that you are going to entertain pretty regularly in the apartment and not spend all of their time prowling after a pair of nylon legs, here are a few simple suggestions on what to wear when the friends come around for a few drinks.

The most important theme in the book is the emphasis on men’s choices: Choosing to entertain was a way to retain control over an area of life that was dominated by women. In its opening section, “Eat,” the Handbook editors laid out rules for making meals that were complex and exotic, as a way to show off skills in the kitchen rather than to feed a family. This approach helped to distinguish between what women did in the kitchen and what men could do (if they followed Esquire’s guidelines).

A bride takes up cooking because she must, whether she’s an eat-to-live gal or just medium-bored with the whole idea. But a man takes to the stove because he is interested in cooking, therefore he has long been interested in eating and therefore he starts six lengths in front of the average female.

The section notes the presence of women in the kitchen, which made the content accessible to married readers who made up the majority of Esquire’s readership, while also making it clear that they should aspire to be more like the bachelor who could cook both gourmet meals and food from a can with the same sense of ease and sense of adventure.

After suffering steam-table tastelessness or misplaced housewifely economy, any palate will perk up at the taste of fresh fish, properly prepared — by a man. (Women don’t seem to understand fish — and, we suppose, vice versa.)

In the Handbook, home décor is also essential to the reader’s self-presentation:

Modern design — modern china and linens were made for men: simple and striking, they are utterly devoid of pink rosebuds and fancy volutes. Your tablecloth or runners will probably be in sold colour linen — wine, gray, bright blue or rust being the most popular… Your china will be plain white or gray, with block initials or a modern striped border, and your silverware will be decidedly streamlined.

The Handbook shows over and over again that women have no choice but to cook bland food and throw boring parties, but a man can choose to do those things better than women, which allows him some semblance of control over his life. It also reinforced the Esquire man’s superiority over women, precisely because he could choose to take over her domain, and with the right training, he could do it in a way that would garner respect from both women and men in his life.

As Playboy overtook Esquire at the top of the men’s magazine market in the nineteen sixties, the importance of consumerism had fully replaced the importance of moral character and societal contributions in forming a true masculine identity. Playboy was more overt in its appeal to single men, who were often younger than Esquire’s target demographic, and who were more comfortable with conspicuous consumption of food, clothes, and home décor. But as second-wave feminism pushed back against the sexism of magazines like Esquire and Playboy in the late sixties and early seventies, and as new models of male parenting and partnership emphasized sensitivity and affection instead of disciplinarian behaviour, hedonism became less fashionable for middle-class men. The rich sixties also gave way to the recession-era seventies, and it was harder to afford (and to justify) the luxury products that came with the swinging bachelor lifestyle. The wealthy bachelor began to look antiquated and passé, as the womanizing behaviour of Esquire men was associated more and more with the newer and brasher magazines like Penthouse and Hustler, which pushed the envelope even further when it came to sexual content.

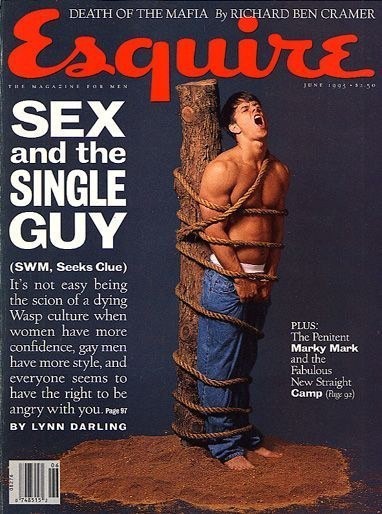

By the nineties, Esquire had rebranded as a classy fashion magazine as newer publications like GQ and Details gained in popularity among readers. In 1995, Advertising Age reported on an Esquire reader survey that highlighted the profile of the typical reader in the nineties:

The typical Esquire reader, as defined by the six types of men defined in the survey, is an ‘ambitious contender’ or ‘comfortable leader,’ according to [Esquire publisher] Mr. Burstein. An ambitious contender represents 14% of the U.S. population, is 31, educated (84% college graduates), and affluent ($58,000 average household income). Almost half, or 49%, are married and 43% have children. An ambitious contender also prioritizes marriage but is not focused on child-rearing, has positive views on women’s roles, is among the most technology-savvy of his peers, banks his cash, and is confident.

Even though almost half of the readers surveyed were married, the bachelor was still present in the magazine’s content and in pop culture more widely. The June 1993 Esquire cover featured Mark Wahlberg tied to a tree, alongside a quote from Lynn Darling’s short story “Sex and the Single Guy”: It’s not easy being the scion of a dying Wasp culture when women have more confidence, gay men have more style, and everyone seems to have the right to be angry with you.” Darling’s protagonist, John Talbot, is a New York City editor who is stuck between old and new expectations of manhood:

Talbot’s generation is defined by the expectations of women, some of them angry, some understanding, all of them players in an edgy, anxious game. He is too young to be the old traditional male, confident, cosmopolitan, able to wield a martini glass and a fly-casting rod with equal precision. And he’s seen what has happened to the New Male, sensitive, caring, and so tedious that women turn from him like revolted gourmets from a tofuburger.

As the story continues, Talbot meets a cool girl named Johanna, who doesn’t want kids and understands that Talbot needs space and time to be himself. Talbot lies in bed at the end of the story, thinking: “To be in bed with your girlfriend, actually sleeping with your girlfriend, that was the most fun. Not having to prove yourself, just regular naked sex.” This combination of sixties womanizing and nineties New Male sensitivity is paralleled in other pop culture products from the era. From the sensitive yet cutthroat venture capitalist Richard Gere in Pretty Woman to Steve Gutenberg’s millionaire with a heart of gold in It Takes Two, the combination of sensitivity and power was an important part of how Esquire treated its readers (and their readers’ wives and girlfriends) into the twenty-first century as the swinging bachelor fell out of fashion entirely.

For the most part, the single man is still presented in Esquire as the one who has the most control over his life, and as a result, is the most masculine one can aspire to be. The magazine’s “Sexiest Woman Alive” is still a yearly event, and Esquire’s April 2015 print issue is devoted to “Women & Men: An Issue On Our Current Difficulties,” as if to suggest that there might be a power struggle at play. Like the “Sex and the Single Guy” feature of 1993, “Current Difficulties” focuses on how men’s lives have changed since women have gained more power at home and at work, implying that men may have made compromises that have negatively affected their freedom. And as in the sixties swinging bachelor era, corporate work culture is still not to blame (neither is patriarchy).

Today’s Esquire appears to be more casual in their approach to “doing” masculinity. There are no sexist cartoons or “scientific” articles about the ineptitudes of women. The magazine started 2015 by inviting the editors of ELLE to critique the issue, as well as removing the “Eat Like a Man” tag from their food section in the March 2015 issue. The new iteration of the Esquire bachelor doesn’t exclusively socialize with men like in sporting culture, nor does he explicitly co-opt women’s roles at home like in the Handbook.

But even as he makes himself comfortable in domestic and public settings, there is still a narrative of conquest and control that has carried through since the Handbook was released: Take the section “Man at His Best,” which features articles on cooking, cleaning, home furnishing, and technology. In August 2013’s tech piece, “Man at His Best” (now shortened to MAHB) explains how to do laundry without using the word “housework.” In a December 2013 article on how to build your own fire pit, the writer claims that the pit will show off building skills and make your backyard look more impressive. There are also numerous fashion spreads and instructional pieces on how to dress your way to success in business and in social life. Maybe most telling of Esquire’s connection to its past is the release of the 2014 book How to be a Man: A Handbook of Advice, Inspiration, and Occasional Drinking, by the editors of the Esquire. Much like the original Handbook, How to be a Man covers a range of essential knowledge for the modern Esquire reader, including “kitchen tools” (pots and pans) and how to carve a turkey as if it were surgery. As with the Handbook, entertaining is not something a man has to do, but is something he wants to do — a way to exercise his freedom in a seemingly constricted world.

Even though the word has been mostly replaced by other descriptors of unmarried men in the city, the symbol of the bachelor is still crucial to Esquire’s sense of itself and its readership. Men are still being introduced to activities like consumerism and duties like housekeeping in a way that emphasizes their freedom to choose these tasks and to conquer them as they might have conquered the frontier two hundred years ago. Magazines like Esquire are vehicles to help guide this thinking, and to assure readers that they’re doing the right thing for themselves and for society as a whole. That assurance relies on traditional figures like a lone wolf bachelor who never compromises for a woman, even if he’s compromised a lot more to fit in with other men. For every crisis of masculinity, there is a bachelor ready to face the threat of a woman by beating her at her own game: domesticity.

Top photo by thatjcrewginghamshirt; scan of the Handbook by Mixed Up Monster Club

Corrections: This piece originally incorrectly dated Donald Mitchell’s book — and he was American, not British. Sorry for the errors!!!

Everything You Laugh At Is Built On Sadness

“Internet humour is not subtle; it largely relies on a childlike immediacy between image and reaction. An amusing graphic of someone falling over is a loop of an instant. There is no time for its backstory, and we do not seek it out. But when we are shown what made the meme it forces us to stop and consider not just that the funny thing happened but why — and perhaps the feelings of the people involved. Our laughter is suddenly less secure. After the Elsa cake, we are adrift: who could have guessed it would contain so much tragedy? That a wonky eye made of sugar came from sick children and bereavement and led to humiliation? It was impossible to know. It was just a funny-looking cake.”

— Look, you know what else has tragedy in its backstory? Every single fucking that has ever happened to anyone. The human condition is one long tragedy interspersed with occasional moments of illusory joy designed to keep you from being fully aware of just how awful it all is. If you strip the Internet of its ability to mock things that might be based in bereavement and despair all that will remain is intersectionality, optical illusions and idiot teens tweeting “YASSSS” and “SLAAAAY” every ten minutes. Oh, and also transient manufactured outrage. Always the transient manufactured outrage. That said, making fun of people in wheelchairs is gross. Actually, everything online is gross. You know what? Maybe let’s just get rid of the Internet altogether. I feel like it would make us all so much happier. Let’s burn it the fuck down. Who’s with me?

The Last Journey

“Later that afternoon I sat with Dad and answered work emails as the Golf Channel soothed in the background. He stirred and opened his eyes, looking simultaneously at me and right through me.

Your loved one may talk about taking a journey, the guidebook said. They may express worry or anxiety about being prepared.

‘Are my bags packed?’ my Dad asked, his voice clear.

‘Yes, Daddy,’ I said, my voice trembling. ‘You’re all packed and ready to go.’

‘I wish I knew where the hell I was going,’ he said.

‘I don’t know, Daddy,’ I said slowly, trying to think of something helpful to say. ‘But I bet it’s really nice there.’”

— You should probably save this piece for when you have a few moments to yourself.

I Dressed Up Like The Little Mermaid For Money

“I had moved to Spain while the country was in the grip of La Crisis (pronounced CREE-sees)- a financial crisis that saw unemployment rates soar. Roughly 26 percent of the country was without a job, and a staggering 55 percent of Spain’s youth were unemployed. Those who had jobs were sometimes no more fortunate, working month after month without pay. I had finally relented to the suggestion a friend had made several months ago. The plan was to dress up as Ariel from The Little Mermaid and sing her hallmark songs down by the Cathedral, where the tourists passed by all day like lemmings.”

The Best Podcast Is One That You Don't Have To Listen To

“The D and K Podcast may have zero episodes so far, but that’s not stopping them from pulling out all the stops engagement-wise and updating their fans. You name it, they’re documenting it: chilling on the patio, chilling on the couch, going to Guitar Center. The account does a great job of mimicking that signature 70% enthusiasm, 30% white-comedy-guys-who-have-no-idea-what-they’re-doing nascent podcast voice.”

Is Armpit Hair Like That Rihanna Video Or Is It Actually A Feminist Act?

“The problem with the Radical Cheerleader view of armpit hair is that we’re all in society and it’s really hard to flaunt something society doesn’t like. It can be exhausting; it uses effort better reserved for, I dunno, many things that are way more important. The other problem is that it’s just not sexy…. Maybe armpit hair is more meaningful as an aesthetic than an act of defiance.”

New York City, July 7, 2015

★★ The subway led away from the dull, thick morning into sunshine downtown. The children traipsed to the office and back, little umbrellas unused, with a minimum of complaint. A bright but heavy shower fell in the afternoon, but the sun came right back. Then the rain repeated, from darker clouds but with the sun angling through below. By the time the boys were shod and umbrellaed to go look for a rainbow, the downpour was cutting off and the sun was no longer distinct.

The Utopia at the End of the World

by Noah Berlatsky

The robots revolt and kill us all. Religious fanatics take over and treat women as chattel. A vicious dictatorship is instituted that kills children for sport. The planet runs out of food, water, fuel, or all of them, and civilization tears itself apart. The aliens invade, the meteor hits, the zombies arise, the rapture raptures. The methods are various, but the message is the same: The world has plenty of problems, sure, but it could be worse. Terminator, The Handmaid’s Tale, Hunger Games, Mad Max, 1984, War of the Worlds. Who can resist the thrilling bleakness of a wholly inimical world?

There’s an impulse to believe that dystopias are a trend, that we like to imagine the end of the world because of the financial collapse, or September 11th, or ecological disaster, or Vietnam. But dystopias are always more popular and more prevalent than their cheerier twin; utopias mostly just sit there, soliciting didactic admiration. Once you’ve achieved perfection, what else is there to do? Much like the Houyhnhnm section of Gulliver’s Travels or Herland, utopic fiction tends to be a tour, rather than an adventure, because as soon as the engine of plot starts grinding, you’re moving towards conflict, disaster, and dissolution. Utopias are static because heaven is outside time — and outside narrative.

Science-fiction and fantasy writer Ursula K. Le Guin has created many utopias and nearly as many attempts to combine heaven with plot. The Word for World Is Forest, from 1972, is about an ecological and spiritual utopia being destroyed by human imperialism; The Dispossessed, published in 1974, is actually subtitled An Ambiguous Utopia, and is about a genius physicist whose personal ambitions create discontent in the anarchist utopian planet in which he lives. His restlessness generates the narrative, with an assist from the rest of the inhabited universe — which is not a utopia, and so causes (fruitful) problems. Le Guin’s most ambitious, and creative approach to utopia, though, is one of her lesser known books: the sprawling, non-narrative Always Coming Home, published thirty years ago, in 1985.

I read the Hunger Games trilogy in two days; Always Coming Home, which is roughly the same length, took me more than two weeks. There’s no mystery as to why: Le Guin’s novel has no story. Always Coming Home does not have a pulse-pounding quest, or an angst-filled protagonist. Le Guin’s father was the noted cultural anthropologist Alfred L. Kroeber, and Always Coming Home is organized as a kind of anthropological study, with numerous short chapters detailing different cultural expressions of a maybe-future Pacific Northwest, populated by a small-scale, peaceful society known as the Kesh. Le Guin, as narrator, figures herself as an explorer or researcher, and devotes sections to her discoveries about Kesh poetry, song, theater, and dance. She describes how and where the Kesh build their houses, and, in impressively mundane detail, their group sex rituals. In the utopia, there are myths, drawings, dreams, alphabets and genealogical charts. There are even some aphorisms (“Cats may be green somewhere else, but the cats here don’t care.”) But there are no grand adventures.

Utopias are popularly thought of, or parodied, as perfect societies, in which everyone is happy all the time and no one wants or suffers. In practice, though, utopian writers frequently present the perfect world not as one in which all evil has been banished, but rather as a society in which the inevitable problems and pains of existence are managed with justice, kindness, and mercy. In that tradition, Le Guin’s utopia isn’t one in which all evil has been banished. There’s still sickness, jealousy, violence, and cruelty. The reason it’s a utopia isn’t because people have been perfected, but because narratives of conflict have been scaled down. Kesh frowns on injustice and greed: “Owning is owing, having is hoarding.” The word for wealth is also their word for giving; it’s a society in which self-vaunting and inequity are quietly but persistently discouraged, which means that people don’t try to get ahead by telling great tales or by blowing each other up.

So the stories Le Guin gives us in Always Coming Home are all smaller than life. A woman who is in charge of watching some of the things in the heyimas (central buildings) starts to keep some bits and pieces for herself — a flute, some cornbread. She becomes very ill with a spiritual sickness. And then, “she got well. Other people looked after the things in the heyimas after that.” Wrongdoing is sickness — its own punishment, which leads to repentance and healing, rather than to revenge, violence, or further misery. Another history talks about a small battle between two groups over a hunting dispute. It ends with a commentary: “I am ashamed that six of the people who of my town who fought this war were grown people.” Theologian Stanley Hauerwas argued in War and the American Difference that war will be abolished not when all wars cease (which is impossible) but when there is no longer ideological justification of war. “War might exist two hundred years in the future,” Hauerwas writes, “but at least we could begin the process [of abolishing war] in the hope that no one in the future would think war to be a good idea.” The Kesh appear to have reached that blessed point; people still fight, but the society as a whole does not justify that fighting, and works, more or less in unity, to prevent it.

There is one exception to Always Coming Home’s studied epiclessness. Amid the poems and play scripts and cultural observations, there is one long story, presented as the written narrative of one of the Kesh, collected along with the other anthropoogical materials. The story is about a hundred pages, split over three parts, and it has many of the features of an honest-to-goodness adventure narrative, including a restless protagonist, a long journey, a daring escape, and a return. This narrative is also, not coincidentally, a dystopia within the larger utopia. This is not a device that originates with Le Guin — many utopias, like Marge Piercy’s A Woman On the Edge of Time and Joanna Russ’ The Female Man — contrast their perfect societies with imperfect ones, present or future. Piercy, for example, has her protagonist travel back and forth between an ideal communal future and a very flawed present. But Le Guin is unusual in that the structure of Always Coming Home allows her to demonstrate how dystopia and narrative are tied together.

The dystopic story in Always Coming Home is titled “Stone Telling,” which is also the name of its narrator. Stone Telling is the child of a warlord from a society called the Condor, who had a tryst with Stone Telling’s Kesh mother on his way to other conquests. Later, when Stone Telling is a young adult, her father returns briefly, and when he leaves, she asks him to take her with him, back to the seat of Condor rule.

The Condor is less like the small-scale, egalitarian Kesh, and more like a hierarchical empire — it’s monotheistic, nomadic, and patriarchal. Or, to put it another way, the Condor is similar to Judeo-Christian culture, but more extreme. “The Condors had purposed to glorify One by taking land, life, wealth and service from other people,” Le Guin writes, clearly referencing Jewish, Christian, and Muslim traditions. The Condor has one God and one ruler; unlike the Kesh, they segregate women and despise them. They are also constantly at war; they mean to spread all across the land, and they use computer records (available to all) to try to reconstruct ancient weaponry, pouring more and more resources into powering their flying death machines.

But it doesn’t work. A society which neglects all its other needs in order to make bigger and more menacing engines of war is, as it turns out, unsustainable. The Condor collapses under its own weight. Not too long after Stone Telling escapes and flees back to the Kesh, the Condor begins to decline; the giant imperial threat simply dissipates as armies and weapons put an unsustainable strain on the society’s food supplies. In another book the Condor would be the central evil to be resisted and defeated, but in Always Coming Home they’re simply a byway, not really more important than a description of Kesh theater. Utopias are often denigrated as too simplistic, too pie-in-the-sky, too good to be true. But Le Guin suggests that it’s dystopia — our dystopia — that is unrealistic. Hate eats itself; give it a little time and room and it will implode. Art, nature, relatonships, love are all more real and more lasting.

History is usually seen as real, utopia as fantasy. But Always Coming Home is predicated on the idea that outside of history is in fact the real bit; it’s history that’s the chimera. In one of the many fragments of anthropological analysis in the book, Le Guin writes that “The historical period, the era of human existence that followed the Neolithic era for some thousands of years in various parts of the earth, and from which prehistory and ‘primitive’ culture are specifically excluded, appears to be what is referred to by the Kesh phrases ‘the time outside,’ ‘when they lived outside the world’ and ‘the City of Man.’” Dystopia, for the Kesh, is not a nightmare of the future, but a nightmare that there is a future at all — and a past, and a series of exciting events connecting the two. To be in history is to be in a dystopic narrative illusion.

In contrast, the Kesh see themselves as part of the world — which means they cannot see it whole, or trace its arc into a pleasurably awful future. Dystopia, for Le Guin, is a self-fulfilling prophecy, not because thinking bad thoughts makes them come true, but because the drive to claim history is how you get the wasteland we’re living in. She asks us to pause long enough to imagine that we can imagine differently — with more fragments, more spaces, and fewer lines in the sand. “No hurry,” she writes in her novel that isn’t a novel. “Take your time. Here, take it please. I give it to you. It’s yours.”