New York City, July 28, 2015

★ Across the flat waters of the river, New Jersey’s windows stared dully through the haze. Sitting down on a bench and staring back for a while seemed as good a use of the day as any. A contrail snake-bellied its way overhead. Down in the upper teens, the walk between avenues was more desolate and defeating than before. Noses wrinkled against the glare. An unassuming pile of trash bags gave off a ferociously sour reek. A very light breeze pushed against the walk back toward the river, making less of an impediment than the hanging humidity was. Even in the shadows of late day, a creeping sweat came on.

Do You Have Permission to Disturb the Peace?

by Emmet Stackelberg

In early January, 1874, pamphlets and posters promoting a mass meeting began appearing all around the eleventh and seventeenth wards of Manhattan, the two political divisions of the city on either side of Tompkins Square Park. The pamphlets were short but emphatic. “Winter is upon us, and nearly all employment has been suspended,” began one. “Cold and hunger are staring in our faces. Nobody can tell how long the misery will last; nobody will attempt to help, if we don’t do something ourselves.” Another called the planned gathering “A MONSTER MASS-MEETING OF THE UNEMPLOYED” and invited the jobless, “irrespective of occupation,” and “likewise all those who are in sympathy with the suffering poor of this city.”

The pamphlets were all signed the same way: “–Committee of Safety.” This Committee was a loose coalition of immigrant groups and labor leaders, formed in December of 1873 to organize protests and marches on behalf of the struggling poor. Future labor leader Samuel Gompers later wrote, “It was a folk-movement born of primitive need.” By January 1874, though, its leadership was in flux, with prominent members resigning, as other labor leaders accused it of being a communist organization. Nonetheless, it claimed to have twenty thousand followers.

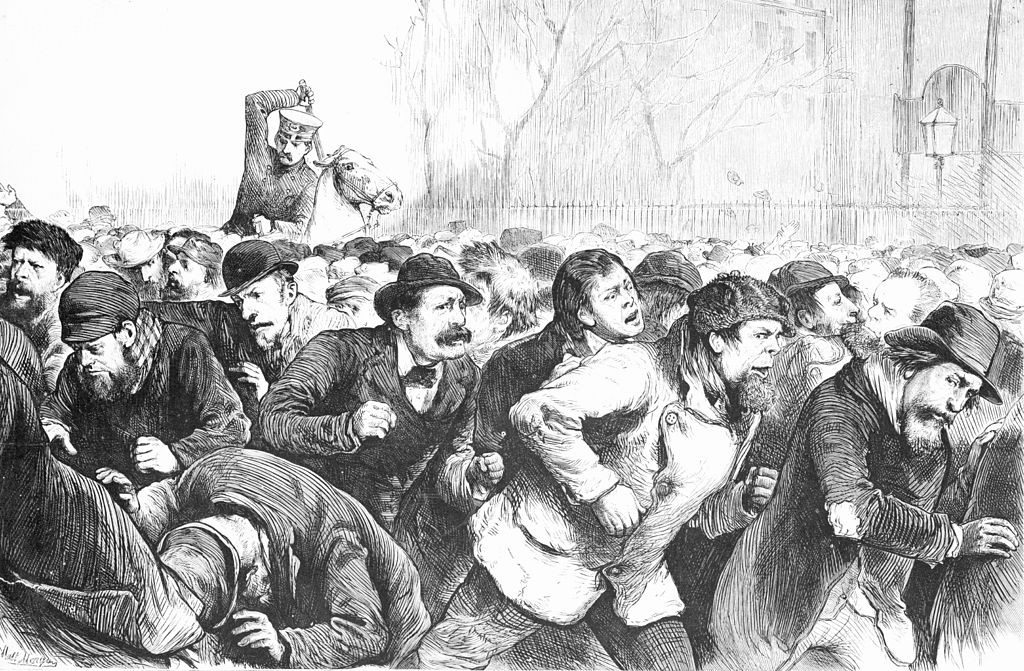

The mass meeting that was held on January 13th in Tompkins Square did not threaten to turn riotous, until, minutes into the proceedings, officers of the New York Police Department charged into the square. After police withdrew the Blood or Bread Riot became, in press accounts, an overreach by the enforcers of order — but over insurgent forces of communism and revolution. It was neither.

The meeting was a demand for help from a community that was struggling during the worst economic recession America had yet experienced. The reasons for the economic depression that had reached its way across the US and Europe by 1874 were myriad: In 1872, twin urban fires in Chicago and Boston destroyed valuable property, affecting investors across the country, while an outbreak of horse flu hurt crop yields; in 1873, Germany and the U.S. abandoned silver-backed currency, which badly depressed the price of the precious metal; and, perhaps most catastrophically, the railroad bubble burst after decades of speculation and frantic building, which precipitated the failures of banks that had heavily invested in the railroads. One such bank was Jay Cooke and Company, which declared bankruptcy in September of 1873, after it could not find a buyer for a slew of railroad bonds. Cooke’s failure paralyzed the market, spurring more bank failures and a stock sell-off; the New York Stock Exchange closed for ten days. By the end of 1873, over fifty railroads had failed. Unemployment soared and among working class families hunger set in. The crisis reverberated across the industrialized world, to Germany, Austria-Hungary, France, Britain and its colonies. Until 1929, this worldwide economic cataclysm was known as the Great Depression.

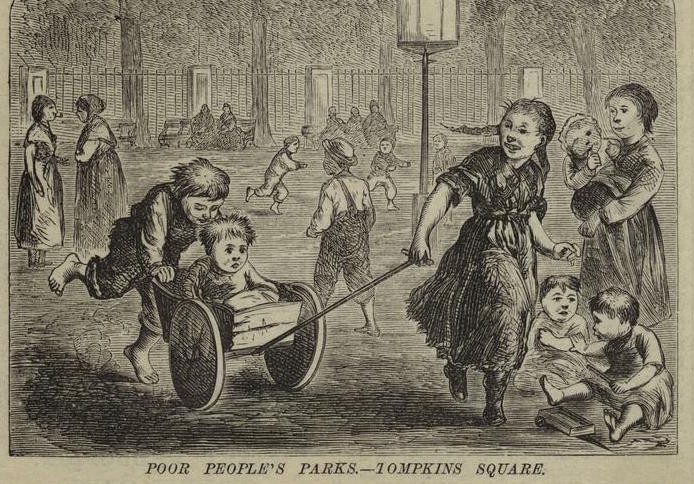

Tompkins Square Park began as swampland owned by John Jacob Astor, who hunted snipe there before he sold it to the city in 1834. Not long after, the city decided to make it a park — preserved from development by its generalized unsuitability, it became one of a Manhattan’s few parks by virtue, really, of its ickiness. After becoming a city park, it was widely used and nicely appointed. By the late eighteen fifties, it was increasingly used as a site for mass meetings decrying working conditions and rallying for union organization. In the eighteen sixties, the military began using it for exercises, and in 1866, the state officially declared the park a military parade ground for New York’s First Division, cutting the square off from public leisure, over the protestations of locals. Residents of the eleventh and seventeenth wards, largely European immigrants, could find a proper park by going to Central Park — still under construction. but already declared the “People’s Park,” if they were willing to travel fifty blocks uptown.

New York law required a permit from the police for any “procession or parade” that occupied a public site, along with a permit from the Parks Department for public gatherings in parks; the Committee of Safety obtained both permits for the protest. But on Monday, the day before the meeting, authorities informed the group that its permits had been revoked. The mass meeting posed too great a risk to “public safety.” The committee was charged with spreading news of the cancellation, but many leaders were away from home, and didn’t find out until late in the night or the next morning. Meanwhile, over the course of weeks, the meeting had been growing in stature, anticipation accumulating like the snow on tenement stoops.

While the requirements for permits had been in place for a couple of years, the idea that authorities could deny a group permission to use a public space was still novel in New York. This instance was to be the first real test of this process. By granting and then revoking the permits just hours before the mass meeting, the NYPD and the Parks Department were effectively forcing a massive group of unemployed workers to test the boundaries of the law. The meeting became a kind of experiment, demonstrators the test subjects, caged off by the bounds of the square.

Inevitably, many thousands of people still assembled the next day at the park. The gathering’s attitude was urgent, but peaceful; it included many women and children. At around 10:30 that morning, fifteen hundred policemen assembled around the park, waiting. Then, they invaded the park, all at once. Mounted police rode horses into the masses; others on foot swung their batons indiscriminately. They arrested a token few, some under the charge of inciting a riot. Gompers, who was there that day, barely kept his head “from being cracked.” He later called it an “orgy of brutality.”

In all, more than forty workers and tradesmen were arrested, most of whom were unemployed, although they plied many trades. In an incisive study of the riot in her book Triumph of Order, historian Lisa Keller compiles a long list of their occupations: brewers and waiters, plumbers and masons, carpenters and painters, stonecutters and machinists, hairdressers and shoemakers. Together they exposed the wide netting of deprivation that had descended on not just some, but all of the trades of the working class in the aftermath of the economic depression that had started the previous year.

In the days after the riot, press attacked both the protestors and the police. New York papers called the assembled communists and immigrant instigators. But many in the press called into question police actions. The Daily Graphic declared that the police “by their excessive zeal for order made an attack which looks despotic.” It continued: “New Yorkers do not live and move and have their being by the suffrance of a squad of blue-coated patrolmen with batons in their hands, whose business is to keep the peace and not to break it.”

The system by which police had to issue (and could at any time revoke) permits for gatherings meant, however, that peace was whatever the police said it was. They were charged with, in the words of the law, furnishing “such escort as may be necessary to protect persons and property and maintain the public peace and order.” They deemed the mass meeting, officially, a break in the peace. The department’s actions signaled the political dimensions of peacekeeping: the voicing of political protest becomes, in the eyes of law enforcement, a disruption of peace.

Nine months later, on August 31st, workers gathered in Tompkins Square Park for the first time since the riot to demonstrate their right to free assembly. The police this time issued a permit, and Governor John Dix signed a pardon for a man who had been sentenced to six months in prison after the riot. It was a celebratory day. John Swinton, editor of labor-friendly newspaper the New York Sun, declared to the crowd of thousands that authorities “have learned that the liberties of the people cannot be trifled with.”

In parks and in squares, symmetry abounds. Benches face each other across a circular clearing; a playground in one corner is matched by another one in the opposite corner. But it’s still jarring to observe how this park’s history has its own kind of symmetry. In August of 1988, over a hundred years after Tompkins Square Park’s first riot, New York police attacked and fought with hundreds of demonstrators gathered to protest a recently instated 1 A.M. curfew in the park. (All parks in New York now have curfews.) The department’s own report on the incident found that the police incited the riot. It sometimes seems that in a city, parks are where history reverberates the loudest.

It Was a Riot is an occasional column about riots in American history.

Top image via Wikimedia; second image via Painting Bohemia

The Comical Ways The Fashion Industry Asks For Attention

What do “Sexy Amish Teen,” “Goth Male Widow” and “Tarzan’s Day At The Beach” have in common, apart from the fact that they will all be playing Coachella’s Yuma Stage in 2019? They are all recent male fashion trends, and they have been assembled in one convenient location for your perusal. Maybe you’ll find a new look!

PREFUSE 73, "Prime Meridian Narcissism"

For various idiot reasons mostly involving self-loathing and an inflated opinion of my own capabilities I just spent close to an hour out walking in our current climatic nightmare. I started to get a little loopy toward the end there and the noises that rushed through my head as I decided that it was either sit down or fall down sounded a lot like this, although this is much better and does not feel like passing out. Enjoy.

The Hill's 2015 50 Most Beautiful List, Assessed

No, Yes, No, No, Yes, No, No, No, Yes, No, Yes, No, Yes, Yes, No, Yes, Yes, Yes, No, Yes, Yes, No, Yes, Yes, No, No, Yes, Yes, Yes, No, Yes, Yes, Yes, No, Yes, No, Yes, No, No, No, Yes, Yes, No, No, No, Yes, No, No, Yes, No

Successful Comedic Actoring: How

Do you want to be a successful comedic actor? Of course you do! Let’s face it, nobody likes or admires you right now and given your terrible personality and lack of future potential in any other industry the only chance you have for people to treat you with respect — or to at least pretend to have respect for you so they can take advantage of you or attain some proximity to your success — is to get yourself on TV or in the movies (or, if you’re really lacking in talent, on the web) as a performer of some kind, and if we’re being honest we’re going to have to admit that you’re not so stunning in the looks department, so really your only shot is making people laugh in the couple of beats before the funny ethnic stereotype character says something about how different it is here in America. It’s not much, sure, but do you know how those people live? It is SO MUCH BETTER than staring at the Internet in the middle of the day and hoping your air conditioner doesn’t conk out. No, you need to be a successful comedic actor and you need to start right now. Here’s how. You’re welcome.

The Fuckbois of Vine

by Helen Holmes

Maggie Lindemann and Carter Reynolds have had a rough relationship. Unlike most teenagers though, they’re partners and social media stars. Lindemann is a musician and an undeniable beauty — visit her website or her Instagram page, and you’ll find portraits drawn by her numerous and adoring fans that lovingly depict her generous brown hair and elegantly angled eyebrows — while Reynolds, one of the several young men who comprise the Magcon tribe of miniature filmmakers, is a Vine idol with 4.3 million followers.

The two have broken up and gotten back together at least twice. Their most recent rupture occurred at the end of May, according to the troopers behind hollywoodtake.com: “Lindemann initiated the breakup after Reynolds yelled at her over the phone. But the Magcon alum insists he had a right to be upset that she had followed an ex-boyfriend on Twitter. And Reynolds maintains that he was ‘rude’ to Lindemann because he was still emotional over the death of his dog Winnie.”

Last month, an explicit video of sixteen-year-old Lindemann and nineteen-year-old Reynolds surfaced on a Mexican blogger’s Tumblr page. In the clip, Reynolds’ requests for oral sex from Lindemann are loud and insistent, despite her repeated assertions that she’s “uncomfortable” with being asked to perform the act on camera. “Oh my gosh, Maggie,” Reynolds replies in an exasperated tone, as if the concept of her refusing him a blowjob while being filmed is incomprehensible.

As the leaked video made the rounds and Reynolds’ fans expressed outrage, he realized quickly that the consequences could spell doom. “Some of you guys have such a HUGE misunderstanding,” he tweeted. “First of all, Maggie and I were dating at the time … it’s not like she was a random girl or a fan. Couples do stuff like that all the time.. and no I’m not saying that it’s the right thing to do but it’s the truth.”

The broken ballad of Maggie and Carter illustrates a larger issue when it comes to reckoning with explosive male Vine fame: the rabid celebrity worship and fandom that teenage girls are so prone to can be legitimately harmful if the celebrities are utter fuckboi assholes. Carter Reynolds, like many of his infernally famous male Vine peers, is a fuckboi down to his marrow.

Just a few days ago, after getting kicked out of VidCon — ComicCon, but for teens and the internet video stars they idolize — Reynolds delivered a heated rant on the live stream video chat service YouNow. In the video, he accused Lindemann of performing oral sex on Hayes Grier (a Vine star recently profiled flatteringly in Buzzfeed) right before she asked Carter to get back together with her.

I hesitated before diving into the minutiae of teenage Vine drama, but the relative dullness of the popular Vine boys doesn’t render the widespread impact of the platform itself less significant. Vine’s peephole-like format means that tween girls (and boys) get to look in on these stars for brief moments, with no context as to their true character or manner of being and no clue as to how they’ll behave when, and if, a camera isn’t trained on them. Tween girls aren’t stupid, but we’re all fools in love, and one could easily see how impressionable brains would be susceptible to high-definition images of cute boys doing cute things, no matter how pointless or idiotic:

But of course, the ardor of teens doesn’t extend solely to idealized romantic partners. If anything, Maggie Lindemann’s story is significant because of how her legions of fans rose up to support her, despite the lengths that Carter went to in his attempts to publicly shame her. When Carter attempted to trend #RespectForCarter in an effort to curry favor, heroic teens used the hashtag to mock Reynolds instead.

But Lindemann, the target of Reynolds’ emotional abuse and attempts at public shaming, has no need for saving. In this instance, at least, it appears that Vine fame may have given Lindemann the space and attention to retaliate against an ex-boyfriend’s attempts to hurt her. “Ya on screen he acts like he loves me and needs me blah blah but in rl he yells at me and threatens me get it thru ur head we are nothing,” she tweeted on July 19th. “Lol hope y’all now see what I’ve known for months now.”

I Heard It Through The Great Vine is an occasional column about Great Vines.

What Would You Do In The 12 Hours Before A Solar Storm?

“A new government report has warned that if a major solar storm — that could knock out electricity and communications for days — hits the Earth, humanity will only get around a 12-hour-warning.”

Types Of Heat, In Order Of Discomfort

17. Parching

16. Piping

15. Torrid

14. Debilitating

13. Smoking

12. Steaming

11. Baking

10. Sweltering

9. Boiling

8. Sizzling

7. Roasting

6. Burning

5. Scalding

4. Blistering

3. Scorching

2. Searing

1. Humid

Movie, You, Old

Do you want to feel old? Look in the mirror. Study your face. Not the lines, although lines you have plenty and you can already see the places where more are soon to show. Not the fatigue under the eyes; that could be from anything, not just from years of living recklessly and without thought for the future, ignoring all sensible decisions as the seconds passed by so silently you never noticed. No, look directly into your eyes. When you stare deeply do you see anything staring back? You do not. You see darkness, a void so black and endless that it stretches into a past before time itself began. Your old dead soul has existed as long as the universe has existed. You are as ancient as anything that has ever walked this earth. You are the living dead, jerking about like some scary articulated dummy that should be stilled forever. Your vacant gaze tells the story of your wizened, corrupted spirit, a spirit that has outpaced chronology itself. Also the Brokeback Mountain movie came out ten years ago, so if you were waiting until the buzz died down to see it in the theatre you might have missed your chance. Also, you’re old.