Sun An, "Full World View"

Cognitive behavioral therapy doesn’t work. Mindfulness is the gluten-free diet for the brain. With every mental fad eventually revealed to be nothing more than a desperate delusion driven by the desire to find life less terrible than both experience and clarity reveal it to be, what are we to turn to next in our ongoing effort to kid ourselves into thinking things will actually be okay? I vote music. Shut down everything else you’ve got going on around you and take ten minutes to listen to this. At the end of it things will seem a little bit better. Of course that is only temporary, and, as with CBT and meditation and everything else, probably illusory, but at least this is free and you don’t have to go somewhere else and sit in a room with other people who are just as annoying as you are. Which has got to be worth something. Enjoy. [Via]

New York City, September 17, 2015

★★★ It was hot, by the thermometer. It couldn’t be denied that it was hot. But the fact could be overlooked under the barrage of brightness — brightness scattering in the fine white morning haze by the ground, brightness buffeting the eyebrows under the midday sky. Now was time to find the sunglasses from the beach and wipe the myriad little fingerprints off them. Even with that, dazzling light flared off blonde hair and bare scalp alike.

How to Create the Perfect Adblocker

1. Block ads.

2. Block sponsored posts. Most of these should actually be pretty easy. Some are already blocked!

3. Block tracking pixels and analytics, because why should they know who’s reading?

4. Block… JavaScript?

5. Block paywalls, which are actually just giant ads for subscriptions.

6. Actually just block everything except text and images, and some gifs.

7. Block affiliate links. This should be VERY easy.

8. Mask URLs. What do they even mean?

9. Block logos, so you’re closer to the writers themselves.

10. Block bylines, so you’re closer to the content itself.

11. Block ALL content deemed “clickbait,” as decided first by a dedicated subreddit and then by user reporting tool.

12. Add profiles, to aggregate all your decisions in one place, and to give you a way to collect your content in one place.

13. Make those profiles public, to allow you to share your content.

14. Put stories in a feed of some sort.

15. Add a re-posting functionality, to allow High Quality ad-blocked content to go viral.

16. Allow video, but block all ads.

17. Allow podcasts, but block all the parts where the host talks about Audible or Squarespace or whatever. This should also be easy, with the user reporting tool.

18. Start keeping track of the content that readers engage with the most, adding this information to a database that can be compared with the clickbait database, which has gotten a little boring.

19. Using this data, present users with a mixture of things they SAY they want and things they actually seem to want.

20. Make it free!!

21. Add ads, to support this app that people love!

With additional blocking by Matt Buchanan

Meat Unhappy

Nestled on a handful of acres in scenic Lancaster County, Pa., the farm is run by a young couple who set out to create a grass-fed “farming oasis” for chickens, turkeys, lambs, cattle, and heritage-breed pigs, according to a video on the website of Whole Foods, which the farm supplies. “I want to see confinement farms be a thing of the past, really,” Philip Horst-Landis, co-owner of Sweet Stem, says in the video. But growing demand for sustainably raised pork challenged those ideals. The couple decided to ditch cattle and poultry to focus on pigs, constructing four greenhouse-style barns that allowed the operation to expand from 80 pigs a year to roughly 3,000. In the process, Sweet Stem stopped raising animals in pasture as shown in the Whole Foods video.

… “The more consumers who demand all of this, the more difficult it is going to be to deliver,” says Janice Swanson, chair of animal behavior and welfare at Michigan State University. “That’s one of the discussions about sustainable food: What is really sustainable, especially for feeding large numbers of people?”

You mean that it is not economical or even possible to produce enough “feel-good meat” — which was always a remarkably wobbly ethical crutch for propping up one’s personal desire to eat animals — to satisfy the demands of hundreds of millions of modern meat eaters? Well I never.

Photo by Farm Watch

Who Does Your Cat Think You Are?

I spend a lot of time thinking about the bizarre life choice I’ve made to keep a small, furry, mid-level predator around my house. I feed it and dispose of its poop and allow it to stay in my apartment rent-free in exchange for, I guess, fun? It is a funny animal that makes strange faces and performs amusing behaviors and sometimes snuggles with me or misses me when I’m gone, which is nice. The other side of the relationship is just as perplexing: What does the cat think I am? It’s an impenetrable question, because the cat, that idiot, doesn’t speak English, but I can’t help but wonder how the cat sees me. As a kitten? A sibling? A parent? A food-and-head-scratches dispenser? It’s not an easy question to answer, but after talking to several cat experts, who are not as weird as you’d think, I think I’ve assembled some semblance of one.

To understand how cats see us, we have to understand how cats think, and, more importantly, how cats behave in social situations. People tend to assume cats are solitary animals, I think because they seem more aloof and willing to spend time alone than dogs do. But cats are not solitary at all. “They clearly can’t be, because otherwise we wouldn’t be able to keep them in our homes, they’d just run away,” according to John Bradshaw, the author of Cat Sense and one of the few scientists who’s actively studying social cat behavior (when he can find funding for it, anyway). The difficulty with studying cat social behavior is that the cat’s wild ancestor, the northernmost populations of the African Wildcat, basically doesn’t exist anymore; African Wildcats are so thoroughly interbred with domestic cats that Bradshaw says it’s likely impossible to find a purebred African Wildcat.

Luckily, we can study feral cat populations. Feral cat colonies are not runaways or strays; they’re cats that were born and exist without direct human intervention. (Feral cat colonies almost always exist thanks to unintentional human intervention — in barns where there are mice, say, or in cities where there’s delicious garbage and rats around.) And by comparing feral cat behavior to that of housecats, we can kind of get an idea of how the cat sees its owner.

A cat colony springs up in a place where there’s enough food to support multiple cats, and safe spaces where the cat can rest and breed — cats are mid-level predators, meaning they both prey on animals and are preyed upon, by animals like coyotes, foxes, and even birds of prey. “Reproduction seems to be the main function of these biological groups,” says Bradshaw. Cats do their hunting alone — unlike, say, canids — but they breed in groups, and care for the young indiscriminately. A cat in a colony will catch a mouse and bring it back for whichever kitten is there, whether or not it’s biologically the hunter’s offspring. Same thing with nursing; cats will nurse basically whoever’s there. Their hormones during that time are bonkers, which is why mother cats will adopt, “anything that’s small and squeaks,” Bradshaw says, even an animal like a duckling that would normally be prey.

The relationship between cats and kittens is described by one set of behaviors — nursing, cleaning, weaning, teaching how to hunt, poop, and cover up poop — while the relationship between adult cats comes with a totally different set of behaviors. Adult cats communicate almost exclusively with body language, conveying meaning through scent marking, tail movements, and physically touching or grooming each other. The behaviors they perform with other adult cats are, mostly, the same that housecats use on us. “We know they’re using the same signals to us as they would do to other cats that they want to get on with, want to collaborate with, want to share space with,” Bradshaw says. There are, though, a few behaviors that cats use for humans but not for other adult cats. The most obvious one is vocalizations; cats are, basically, silent amongst themselves in feral colonies, but noisy to varying degrees with humans. “The explanation that’s been given, and I think it’s right, is that it’s almost entirely learned behavior,” Bradshaw says. “Meowing, in particular, is something that’s very rarely done by cats living in the wild, but is very common [in homes].”

There’s a lot of weirdness going on with cat vocalizations, but there’s evidence to back up the theory that meowing is a learned behavior, a specific response cats give when presented with a useful but stupid creature like a human and not used in other situations. Though we can tell whether any cat’s meow is “pleasant” or not, a study from 2003 indicated that cats develop private languages with their owners — that a cat’s owner can distinguish, roughly, what a cat wants or means with its different meows, yowls, and chirps, but that these different meanings are not universal; subjects who listened to recordings of unfamiliar cats were totally unable to figure out what the cat wanted.

Cats do sometimes make little vocalizations with kittens, but meowing, the most common vocalization used for humans, is basically unknown in any other communication. “Each cat learns this individually, that meowing at their owners gets a response,” Bradshaw says. That all suggests that vocalizations aren’t a hint that a cat sees us as a kitten, but that the cat is merely adapting to the strange needs of a human, which doesn’t understand the cat’s very obvious nonverbal cues.

But what, I asked, about the the behavior wherein cats that are allowed outdoors will sometimes hunt and leave a mangled corpse of a mouse or small bird somewhere in its owner’s house? A standard interpretation of that behavior is that the cat is bringing a present to its owner, and given that in feral colonies, cats are solitary hunters and only provide food to kittens, that would suggest that cats see us as kittens. “Here you go, you dumb idiot human, I know you can’t hunt for yourself so I did it for you,” the cat seems to say.

Bradshaw doesn’t think so, though: he thinks that behavior is a combination of instinctual behavior and the simultaneous uselessness of that instinct when a cat lives as a pet. “I think there’s a perfectly reasonable explanation for that, which is the cats are not actually bringing you food at all, but bringing food into the house because that’s a safe place to eat it,” he says. Cats in the wild don’t eat prey where they catch it; because cats are also prey for other animals, they want to bring food somewhere more safe where they can be free of coyotes or whatever. But that gets all screwed up, because a housecat’s safe place isn’t a corner of a barn, but a house.

So the cat brings its newly caught food into the house, where it realizes, oh, wait. This food stinks. “Cats rarely eat what they catch anyway,” says Bradshaw. Housecats, according to Bradshaw, much prefer commercial cat food to newly-dead animals; their instincts compel them to hunt, but when they’re hungry, they go for the bowl of chicken-drumstick-shaped food pellets, the McDonald’s of pet food. So they leave their prey in the safe place, but don’t bother eating it. For Bradshaw, this behavior has very little at all to do with humans.

So how does Bradshaw think cats see humans? “A simple summary would be, for me, that cats see us as adult cats, but ones which are different in behavior.” The way I rephrased this to Bradshaw, which he did not refute, is that cats see us as giant, weird, dumb adult cats that if treated in a certain way can provide food and head scratches. Where this kind of breaks down is that, well, a cat can’t exactly start talking or eating with a fork to demonstrate that it knows we are not a cat. “Their behavioral repertoire is really quite limited,” says Bradshaw. Basically, the way cats treat any animal falls into one of three categories: an animal the cat can eat, an animal that can eat the cat, or an animal that fits into neither of the prior two categories that could still somehow fulfill a need like reproduction or affection.

To get a cat to file a non-cat creature into that last category, it must be introduced at a very specific point in the cat’s life: Before it reaches the age of around eleven or twelve months. After that, all non-cat animals are either prey or potential death, including humans, dogs, horses, raccoons, and Golden Snub-Nosed Monkeys. If you introduce a cat to a dog in that timeframe, the cat will grow up seeing dogs as, basically, alterna-cats: A neutral animal that cannot be eaten but also will not attempt to eat the cat. Same with a human, except if you teach the cat at that young age that a human can be not just a neutral but an ally, a creature that will provide the cat with food and head scratches, well, that cat will grow up seeing humans as something very similar to a fellow adult cat — except even better, when the big dumb idiot can actually understand what the cat is trying to say.

Because we can’t talk to the cat to find out what it thinks, it’s possible that saying “cats see us as weird dumb adult cats” is no more correct than saying “we humans see cats as semi-independent, fur-covered, mobile, weird baby humans.” But that’s maybe that’s not that far off, either.

Sexwitch, "Ha Howa Ha Howa"

How long has this week been? That Slate piece on personal essays only happened five days ago. I know, I can’t believe it either. Anyway, it’s Friday, we made it, in a few hours we will be free for an impossibly brief period of time before we have to do it all again. It sucks when you think about it but given that it’s all we’ve got we may as well make the most of it. God knows things aren’t going to get better. Also, this Bat for Lashes side-project is pretty great, so at least you have something this morning to enjoy.

New York City, September 16, 2015

★★★★★ The river lay smooth beyond where 61st Street dropped away to the west. There was no need to put jackets on the children; the air in the shade was humid but still a little cool. The steel and glass reflections at the corner of Alice Tully Hall were so strong that for a moment they formed a cage, making it impossible to judge where to go. The side plaza at Lincoln Center smelled of swimming pool: a note of chlorine, a note of cocoa butter. Jet planes crossed the sky at right angles, leaving no trails. Pigeons, near immobile and loaflike, occupied the green of the chained-off grass roof. Shadows filled the plaza till there was only a little patch of sun at the top of the stairs and new reflected sun off tower windows. A toddler in cuffed jeans padded in white-on-black Adidas toward the corner of the dark pool. All was calm and comfort. Only waning batteries and waxing obligations offered any reason to move on.

Lego City

by Brendan O’Connor

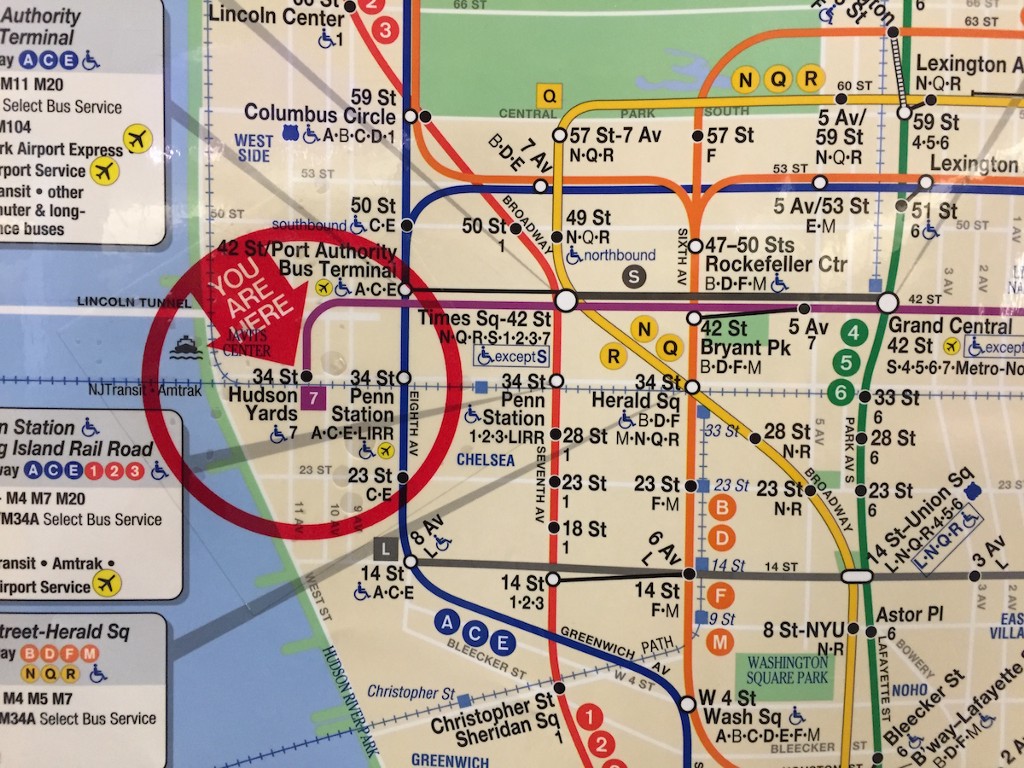

On Sunday, New York City got a new subway station: An extension of the 7 train, which has been extended a mile-and-a-half, from Times Square to 34th Street-11th Avenue in West Chelsea. The station was supposed to open before the end of 2013, after six years of construction, but the opening was delayed by issues with the custom-designed, diagonal elevators — thought to be both less expensive than more conventional elevators and more equitable to wheelchair users — manufactured in Como, Italy. The elevators, though, failed a factory test that July. In December, the MTA arranged for the station to be opened for one day, so that then-mayor Michael Bloomberg, whose administration agreed to finance the two-and-a-half billion dollar project as part of the nearby Hudson Yards development, could take a ceremonial ride.

The new station is the city’s first in over twenty-five years, and the first paid for by the city in more than sixty. “Just like in the 20th century, when the 7 train created neighborhoods like Long Island City, Sunnyside and Jackson Heights, this extension instantly creates an accessible new neighborhood right here in Manhattan,” MTA chairman Thomas Prendergast said at the opening ceremony on Sunday, which must have come as a surprise to the people already living in West Chelsea, a neighborhood already being transformed by the High Line. “This extension connects this extraordinary development happening here — a whole new city being created within our city — connects it with thousands of jobs in neighborhoods like Flushing and in central Queens, bringing people from those neighborhoods to the jobs here,” Mayor Bill de Blasio said. The New York Times closed its story on the ceremony with an anecdote from local resident Yolande Makha, 42, who took the train with her five-year-old son to Jackson Heights, Queens, to buy food and spices. “It was so easy for me to go to Jackson Heights today,” she said.

If everything goes according to plan, the twenty-billion-dollar residential and commercial complex at Hudson Yards, stretching from West 30th to West 34th streets and from 10th to 12th Avenues, will be the largest private real estate development in United States history. Fifteen of the sixteen planned buildings will be built on two platforms erected over the Long Island Rail Road’s active rail yards and four other train tunnels: the Empire Line Tunnel, the under-construction Gateway Tunnel, and the two North River Tunnels. Construction of the platforms alone will cost Hudson Yards’ developer Related Companies over a billion dollars. The eastern platform, which the Real Deal reported in February will comprise fourteen thousand cubic yards of concrete, is being built first and will weigh more than thirty-five thousand tons; Related has also already ordered twenty-four thousand tons of steel for the platform.

Somewhat incredibly, developers like Related have lately been dealing with a glass shortage: Many glass manufacturers shuttered their businesses during the recession of 2008 and 2009, and now demand has outpaced supply. Prices for the metal-framed glass panels that sheath skyscrapers have risen more than thirty percent in the past eighteen months, the Journal reported earlier in September. Such glass accounts for about a quarter of a given construction projects budget, one developer estimated. “Nowadays, the glass guys are dictating the timetables of a project to us, instead of the other way around,” said commercial developer Ralph Esposito, whose Lend Lease Corp. has nearly thirty high-rise towers under construction around the country. “I don’t think people had the leap of faith that the [real-estate] industry would be as strong as the run we’re currently on.” Rather than wait for supply to increase again, Related is getting into the glass game, starting a company called New Hudson Façades with specialty-metal manufacturer M. Cohen & Sons in Linwood, Pennsylvania, where the developer has opened a sixteen-million-dollar, one-hundred-eighty-thousand-square-foot factory.

The first building scheduled to be completed at the site, in 2016, is the fifty-two story office tower at 10 Hudson Yards, which straddles the High Line with a sixty-foot arch. (More than half of Hudson Yards’ seventeen-and-a-half million square feet will be used as office space.) The anchor tenant will be Coach. In 2012, under the Bloomberg administration, Related received an exemption to a bill mandating that future workers at new developments subsidized by the city be paid a living wage (currently, a little over thirteen dollars an hour). At the time, the Wall Street Journal reported, Related said it was negotiating contracts with tenants that would have been difficult to finalize without the exemption. De Blasio renegotiated the deal within a few months of taking office: Related will pay its workers a living wage, although Coach will still be exempted. (It is easy to get the impression that the city’s investment in the 7-train extension and the development of Hudson Yards — towards which the city will pay nearly a billion dollars — isn’t really for people in Jackson Heights and Flushing. Hmm.)

Thirty-four percent of Hudson Yards will be residential: The first two residential towers to come on the market will be at 15 Hudson Yards, which will include both condominium and rental residences, and 35 Hudson Yards. (One Related property, the hundred-and-thirty-nine-unit building at 539 West 29th Street — not really a part of Hudson Yards, but definitely nearby! — will be a hundred percent and permanently affordable.) “With its iconic tapered design, unobstructed views of the city and Hudson River and abundant amenities, 15 Hudson Yards will be the ideal place for New York’s creative visionaries to live,” Related’s website reads.

Meanwhile, the residential 35 Hudson Yards, on the corner of 33rd Street and 10th Avenue, will also include an eleven-story, Equinox-branded luxury hotel, expected to open in 2018. The hotel — Equinox’s first — will include, at sixty-thousand square feet, the largest-ever Equinox gym. Equinox expects to open as many as seventy-five hotels around the world, the Journal reported in April. “We are appealing to the discriminating consumer who lives an active lifestyle and wants to have that as a hotel experience,” said Equinox chief executive Harvey Spevak. As it happens, Related is the company’s majority shareholder: A spokeswoman said that the developer expects to invest or raise “several billion” dollars over the next few years towards Equinox hotels. At the other end of the same block, on the corner of 33rd Street and 11th Avenue, the ninety-two-story skyscraper at 30 Hudson Yards, scheduled to be completed in 2019, will be the city’s fourth-tallest building will include its highest outdoor observation deck, one thousand one hundred feet in the air, the New York Post reports — fifty feet higher than the Empire State Building’s eighty-sixth floor deck. The deck will also include an unspecified “thrill-seeking element,” a Related executive told the Post.

In April of last year, Related announced a partnership with New York University’s Center for Urban Science and Progress to make Hudson Yards the country’s first “quantified community.” The data Related plans to collect is comprehensive: pedestrian flow, street traffic; air quality; energy use; waste disposal; recycling; workers’ and residents’ health and activity levels. “I don’t know what the applications might be,” Related Hudson Yards president Jay Cross told the Times. “But I do know that you can’t do it without the data.” Every apartment at Hudson Yards will come with a smart thermostat: “You can’t get that from any old business in town,” Cross said. According to the Times, the NYU center is supported by corporations interested in the development of “smart cities” like I.B.M., Microsoft, Xerox, and Cisco.

On Wednesday, I walked from the new 34th Street station to the High Line. (“Smells clean!” a fellow straphanger remarked as we stepped off the train.) To the west of 11th Avenue, trains packed tightly in their yard waited to be called out onto the Long Island Rail Road, silver tubes shining in the sun. Soon enough, they will be buried. To the east, buildings stood in various stages of accretion — steel girders dwarfed by the already towering 10 Hudson Yards, sheathed in glass. Three men in collared shirts and ties stood on a rooftop on the other side of the elevated park, watching as pedestrians stopped to look out over and into the construction area. Pits were dug and beams carried. In a corner, beneath some scaffolding, visitors assembled tens or maybe hundreds of thousands of white Lego pieces into a messy, teetering city. “Come build with us!” a sign invited. Everyone was sweating.

Renderings by Related Companies

A Poem by Jameson Fitzpatrick

by Mark Bibbins, Editor

Threesome with Ambivalence

Bridges are beautiful

but is there no such thing as bending too far,

taut between wish and command?

To make room in the bed then,

slow evacuation of the self: who was I before I

was yours? what did I want

more than anything? Smoke

in the afternoon, clothes strewn across the floor,

why shouldn’t love be like this?

If it hurts, if it feels good

(blur of brushstroke down my spine, that artful)

— don’t I touch him in kind?

Your old lover’s husband

in from California for the weekend, to want him

between us but to want nothing

between us. Not but but and,

taking him into our mouths in turn, while down in D.C.

the Supreme Court hears arguments

for and against marriage.

I, too, have two opinions: oh yes God yes fuck yes

and the one that dissents: Stop

worshipping his nipples already;

you shall have no other God before me. But before me

your life stretches back a steady succession

of orgies, freedom lived out —

shouldn’t I follow sometimes, off the path

and into the woods or fray or baths?

I do. I choose you,

which is to choose him and the others and to say

Everything I was ever told of love

was so simple as to be untrue.

Let me see for myself what you desire beside me.

Let me look it in the face and kiss him.

Jameson Fitzpatrick teaches at NYU and is at work on his first manuscript.

You will find more poems here. You may contact the editor at poems@theawl.com.

Why I Hate Glasses

“The grass upon the mountain sides had turned to gold.” — Heidi, 1881

I didn’t know when I woke up this morning that something horrible was about to happen, but in hindsight I should have, because my glasses, when I reached for them blindly from my position in bed, were not where I expected them to be: they were a few inches to the left. It was 8:15 am, and we’d all slightly — happily, I thought — overslept. My daughter needed to be at school at 9:00 am, so we had to move pretty quickly to make that happen. I jumped out of bed, went into the bathroom to splash water on my face, brush my teeth, and put my contact lenses in before going to get my daughter up. This is what I do every morning: Even if the baby is crying in her crib, I at least do the water and the contacts. I can sometimes get away with not brushing my teeth for a while, but I cannot abide by wearing my glasses for longer than it takes me to get from my bedside to the bathroom.

Less than a decade ago, I got into “wearing glasses” for a while even though my vision is so poor that contact lenses are really the only option for seeing clearly. Glasses offer some distinct advantages over contact lenses: They’re for lazy people, and though I’m not r e a l l y lazy I am slovenly, so the idea of plunking some glasses on my face rather than going through the whole contact lens ritual — washing hands, washing lenses, removing them at the end of the day, repeat — appealed to me. I also thought, in that phase, that glasses might make it less obvious that I didn’t wear makeup and sometimes had bad skin; I looked good in glasses, my boyfriend (now husband) assured me. I got a few pairs of very cute frames, some of which I still wear to this day for one minute each morning as I stumble from the bed to the bathroom.

That phase ended abruptly one afternoon in 2008 when I went to see my optometrist — the one who had fitted me for all of my new fashionable glasses — and he asked me how I was feeling. “I can’t really see anything,” I told him. One of the upsides, I went on, of living in New York City was that I never really needed to drive anywhere, so my vision didn’t have to be a hundred percent. “Your vision is 20/20 with these eyeglasses,” he assured me, “but it’s true that going back to contact lenses would bring a lot more clarity.” I had heard this story before. I started wearing glasses in second grade when I failed an eye exam at school. I’d known for some time that, clinically speaking, I “couldn’t see shit,” but I hadn’t said anything to anyone because I didn’t want to wear glasses. This was in 1986, and far pre-dated the notion of sexy geeks or cool librarians: Wearing glasses was likely to subtract my cool points, and I already had so few to spare. I didn’t even have front teeth yet, so I definitely couldn’t risk eyeglasses. But there in the optometrist’s office a few days later, with my mother by my side, I saw the world as I probably had never done before: well. Things suddenly appeared sharp and vivid. Life seemed full of new possibilities, like seeing the blackboard or the television clearly.

I started wearing glasses in second grade when I failed an eye exam at school. I’d known for some time that, clinically speaking, I “couldn’t see shit,” but I hadn’t said anything to anyone because I didn’t want to wear glasses. This was in 1986, and far pre-dated the notion of sexy geeks or cool librarians: Wearing glasses was likely to subtract my cool points, and I already had so few to spare. I didn’t even have front teeth yet, so I definitely couldn’t risk eyeglasses. But there in the optometrist’s office a few days later, with my mother by my side, I saw the world as I probably had never done before: well. Things suddenly appeared sharp and vivid. Life seemed full of new possibilities, like seeing the blackboard or the television clearly.

I decided then that I would wear the glasses as prescribed. I wouldn’t pull them out when I needed to “read” or “see” something. I would wear them from the time I awoke until the time that I went to bed. Of course, I was only seven or so, and this meant that numerous pairs of glasses died in my possession, carelessly stepped on while wrapped up in a towel poolside at my friend Allison’s house. I was a ball of anxiety there in the pool, calling “watch out for my glasses!” to the obnoxious group of girls — my “friends” — cavorting near my life-saving medical devices. “Not my fault!” I cried later that night after walking through what I thought was an open door but was actually a closed sliding screen door. I walked right out onto that fucking deck like it was no big deal. The screen was destroyed; wasn’t my fault that door was in the way. How many times did I proudly get on the school bus with taped up glasses, explaining breathlessly “my new pair will be in next week.” I never successfully had a backup pair of glasses for more than a few months. My vision kept getting worse so, inevitably, when my primary glasses died an awful death, my backup glasses got pulled out of my top dresser drawer, they were always a few prescriptions behind, resulting in even more minor injuries to myself or my surroundings.

1992 was a big year for me, and not just because I saw Ministry and Ice Cube at Lollapalooza. I was in tenth grade, and my parents finally deemed me “responsible” enough for contact lenses. I was fitted with expensive, non-disposable gas-permeable hard contact lenses. They cost like a hundred dollars a pair, and if I lost one, I had to wait at least a week for a replacement. Of course my parents bought me two pairs, but they flew out of my eyes on roller coasters, were easy to accidentally bite in half when I put them in my mouth to clean them off, and they were nearly impossible to find if I dropped one. They were so tiny and fragile, I was chewing through a pair every month or two. But they were also life-changing. For the first time since that first time at the optometrist’s office in second grade, I could see EVERYTHING. It was amazing, how much detail I’d missed out on! Never again would I make the mistake of wearing glasses when the contact lens option was present, I thought.

“It’s true,” the optometrist said to me in 2008, “that contact lenses would give you more clarity.” I agreed. After months of breaking my own rule never to wear glasses, I was done. I decided I should get some contact lenses, immediately. “Would you like to try soft contact lenses, instead? The vision won’t be quite as good as the hard lenses, but it will be much better than your glasses.” Yes, yes I would like to try them. And it turned out they were just fine. As I washed my hands this morning, blindly feeling around for a hand towel, my mind flashed to last night, when I’d fallen asleep on the couch with my contact lenses still in. This happens all the time, and though back in the hard contact lens days that spelled instant tragedy (corneal ulcers, infections that can cause blindness), these days it rarely does. But I knew, too, that when I had stumbled into the bathroom to remove them, I had still been half asleep.

As I washed my hands this morning, blindly feeling around for a hand towel, my mind flashed to last night, when I’d fallen asleep on the couch with my contact lenses still in. This happens all the time, and though back in the hard contact lens days that spelled instant tragedy (corneal ulcers, infections that can cause blindness), these days it rarely does. But I knew, too, that when I had stumbled into the bathroom to remove them, I had still been half asleep.

I opened the right side of the case and there it was: my contact lens was destroyed, ripped in half by the screw top of the container the night before. I briefly thought about trying to put it in my eye before laughing and reaching in the cabinet under the sink for a new pair in the box. But the box was empty. I scrounged around in there, pushing away unused face masks and lotions, a Sephora fire sale explosion, grasping desperately for what I absolutely must find and for what I suddenly knew was not there: I was out. Kaput. All done. No more vision aids in here! I haven’t run out of contact lenses since I have had control of my own finances. I have always — even in the hard contact days — made sure I had other options. But my daughter was awake and I had less than half an hour to get her to school. I looked at my glasses sadly and put them on my face. The rest of the morning passed, to the view of an external party, uneventfully. I drove my daughter to school without crashing into anything, even though there were truckloads of city employees on my street who had somehow decided that today was the day the town’s trees should be pruned. I came home, had coffee. I read some emails. I oversaw the building of my new little desk (I’m writing at it right now, it’s great!) in my new little office. I counted out the minutes until 10:00 am when the optometrist’s office opened so that I could call and make an emergency appointment. When I did call, at 10:03 am, the woman who answered the phone was having computer trouble and asked me to call back in five minutes, so I did, and made an appointment for 1:30 pm. Nothing wrong here, but inside was all turmoil. I counted minutes. My glasses kept slipping down my nose, and though I could see alright, nothing felt right. Everything seemed off. I’d woken up with at least a small dose of “seize the day” and now I felt that life wasn’t even worth bothering. I was so irritated I couldn’t concentrate on my work. I harassed myself silently for acting like a baby, but it was inescapable: I can’t see shit! Of course, I can see shit: having grown up with a parent who was actually nearly blind made me profoundly aware of just how irrational my feelings were; and yet, I couldn’t stop feeling off.

The rest of the morning passed, to the view of an external party, uneventfully. I drove my daughter to school without crashing into anything, even though there were truckloads of city employees on my street who had somehow decided that today was the day the town’s trees should be pruned. I came home, had coffee. I read some emails. I oversaw the building of my new little desk (I’m writing at it right now, it’s great!) in my new little office. I counted out the minutes until 10:00 am when the optometrist’s office opened so that I could call and make an emergency appointment. When I did call, at 10:03 am, the woman who answered the phone was having computer trouble and asked me to call back in five minutes, so I did, and made an appointment for 1:30 pm. Nothing wrong here, but inside was all turmoil. I counted minutes. My glasses kept slipping down my nose, and though I could see alright, nothing felt right. Everything seemed off. I’d woken up with at least a small dose of “seize the day” and now I felt that life wasn’t even worth bothering. I was so irritated I couldn’t concentrate on my work. I harassed myself silently for acting like a baby, but it was inescapable: I can’t see shit! Of course, I can see shit: having grown up with a parent who was actually nearly blind made me profoundly aware of just how irrational my feelings were; and yet, I couldn’t stop feeling off.

This was the first time I’d ever been to this eye doctor’s office, because we just moved a few months ago. She was great, she was funny. She understood — my prescription, -7.50, speaks for itself. “I know it’s crazy,” I said, still pissed off about having to undergo the pressure test where the machine blows air into your eyes, “but I don’t feel like myself. I can’t see well, I’m angry. So even if they’re not the right contacts, I hope you can give me some today.” She fiddled with the machines and turned knobs, taking notes and making jokes with me. “Read the last sentence for me, if you can,” she said.

“The grass upon the mountain sides had turned to gold,” I read slowly, stopping and starting a few times, not because I couldn’t see but because the sentence didn’t sound right. I scrunched up my nose. Nothing was right today.

“What’s wrong with that sentence?” she asked, “if you don’t mind me putting you on the spot.” I wasn’t sure. “Mountain sides should be one word, I’m pretty sure,” I said, “but it’s all around a kind of weird sentence, right?” She laughed, “I’ve always wondered where that’s lifted from, but I’ve never looked.” “That’s interesting,” I told her, “I should write about that.” Ten minutes later, I was on my way, new contact lenses in my eyes, my glasses discarded on the passenger seat of my car, where they remain.

Giph by Cheezburger