Privacy: The Sequel

One thing that makes caring about tech privacy issues difficult is that rather than getting solved, they often just get replaced with bigger ones. Mounting a fight against red light or speed cameras might slow their adoption, or get a few taken down, or win some lasting protections against overuse of the data they produce. Then, a few years later, the terms of that discussion are overtaken by the availability of high altitude drone-mounted cameras that constantly photograph entire cities, allowing every car to be tracked constantly. Using credit cards meant accepting the paper trail they produce behind your daily spending; now, your cellphone company — as well the companies that make software for your phone — knows where you are at all times. In 2005, the NSA wiretapping phones without warrants was a shocking scoop. In 2013, we found out the NSA had everything. Ten years ago, Google placing ads in Gmail was seen as an egregious violation of email privacy. Today, Google Now reads your email to tell you when your flight is going to leave, and what time to leave your house, which it can show you in photographs taken from space or from the street out front. The surveillance state is great at confirming our worst vague fears. In consumer tech, the arc of privacy bends toward “well, I’m using this anyway.”

Earlier this month, as our long national conversation about ad blocking and tracking was just heating up, Nautilus published a story titled “What Searchable Speech Will Do To You,” which made a convincing case for the urgency of the following question: “Will recording every spoken word help or hurt us?” The implication, of course, is that the recording is going to happen no matter what.

If yesterday’s unease about privacy seems quaint by today’s standards, and if tomorrow’s will have the same effect, the privacy issue becomes both more pressing and less approachable. These are the conditions that create cynicism and despair. They suggest not just that “privacy” is a lost cause — as Google’s Eric Schmidt clumsily attempted to explain in 2009.

They present, against all-consuming inevitability, one solution for continued sanity: a redefinition of the concept. Which brings me to this remarkable document from the Brookings Institution: “The privacy paradox: The privacy benefits of privacy threats,” by Benjamin Wittes and Jodie C. Liu:

In this paper, we want to advance a simple thesis that will be far more controversial than it should be: the American and inter- national debates over privacy keep score very badly and in a fashion gravely biased towards overstating the negative privacy impacts of new technologies relative to their privacy benefits.

This is an argument that challenges not just the loss-of-privacy tech narrative but one of the premises that has produced it — the “default assumption” that “as technology develops, the capacity to surveil develops with it, as do concentrations of data — and that such capacities and data concentrations are inimical to privacy values.” This, the paper suggests, is an insufficient account of technological change.

Perhaps the lowest hanging example is Google. It’s a service patronized by most of the internet-using public, and has gathered an unprecedented amount of information about the humans of the world. The Google search box functions as place to look for help and to confess.

Target Manhattan location open hours

precedes painful

urination cause

right before

how to tell if im depressed

Together, these searches create a worryingly intimate profile — one that arguably overrepresents your most sensitive online activities. A profile that belongs to a multi-billion-dollar advertising company. A profile associated with your real name, email, location information, and chats.

But! But. But. What about all the things Google allows you to find, or do, that would have required either risky or impossible behaviors elsewhere? A small-town teen can seek medical information without going to the doctor, who might know her parents. The acquisition of porn, the paper points out, now happens at home, rather than at the magazine rack or the video store. The authors’ broader diagnosis:

The result is a ledger in which we worry obsessively about the possibility that users’ internet searches can be tracked, without considering the privacy benefits that accrue to users because of the underlying ability in the first instance to acquire sensitive material without facing another human, without asking permission, and without being judged by the people around us.

Consider an older technology in these terms:

Create phone lines for the first time and you create the possibility of remote verbal communication, the ability to have a sensitive conversation with your mother or uncle or lawyer from a distance. It is only against the baseline of that privacy gain that you can measure the loss of privacy associated with the sudden possibility of wiretapping.

I can’t stop thinking about this paper. Not that I find it totally persuasive! Its central worry seems to be that our “ledger” or, later, “roster” of technology’s privacy impacts is faulty, or doesn’t fairly represent the semi-related privacy boons we enjoy thanks to some of the most powerful companies in the world, which is a problem for… those companies? Facebook gathers data and makes money from it. Facebook allows people to communicate with each other individually or in groups, out of sight or in full view. It’s not clear to me why these two facts, which pose very different questions about power and control, must be placed on one scale of good and harm, and rendered in its units.

What do we gain, exactly, by cramming so much meaning into the concept of privacy that it better conforms to our economy’s self-perpetuating concept of progress? It’s less clarity than comfort. The paper came out shortly before the Ashley Madison hack, which is fun to analyze through its lens. Ashley Madison was the ultimate privacy-enhancing service, until it wasn’t.

But the paper’s authors are aware of the boldness of their claims — they understand, I think, that making such a counterintuitive argument, and one that might be accused of merely rationalizing of power, demands a little humility:

The key point here is not that big data does not have some, maybe many, negative consequences for privacy — some of them quite severe. It does, and we are not trying to argue that the privacy literature errs in drawing attention to those negative impacts.

It is a question, instead, of “types” of privacy and proportion. But the reason I can’t stop thinking about this paper is because of how I imagine its ideas might be deployed, or selectively represented (or simply arrived-at by actors with a real stake in the definition of privacy). It doesn’t take much imagination to see some major privacy questions arriving ever more quickly. Both Android and the iPhone listen for voice commands at all times; Apple is getting into healthcare as it sells its first wearable; wearables in general are guaranteed to become more powerful, cheaper, and less burdensome. Companies will be making some huge asks, or just making equivalent assumptions: think about the data required to enable predictive shopping. What about the first device that promises total speech recall? The rise of a dominant, consumer-facing health records company? An actual convergence of the comically fragmented Internet of Things? Companies may need to present alongside their new products a method for staying sane — a new framework for consumption; or a misdirection; or, depending, a polite lie–and I think it might sound something like this paper, minus the caveats, and in far fewer words.

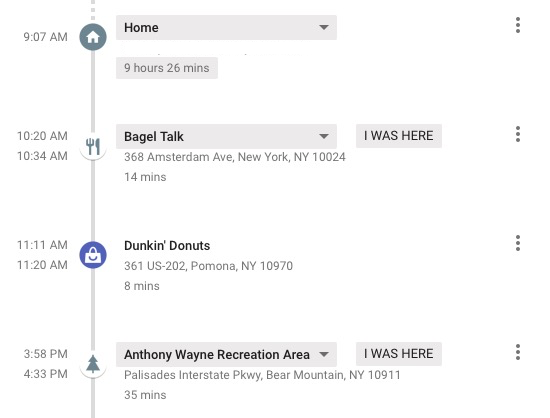

I came across this paper because it was approvingly shared on Twitter by a venture capitalist — an interesting observation, some food for thought. But it’s plausible, I think, that the argument for the redefinition of privacy — not this paper’s, but a definition like it–is assured no matter what. It may never need to be articulated by Amazon, or Google, or Facebook. In fact, doing so would be suspicious and distracting. It will instead be cobbled together after the fact, and only to meet the low demands of the user’s rationalization to self. This seems to be what’s happening reliably now, already. Remember the The Xbox One’s always-on Kinect camera? Amazon’s always-listening Echo device? FourSquare changing from a service that lets you “check in” to a service that asks you to review, automatically, places it can tell you’ve been? Google Maps, in addition to being a service you ask for directions, becoming a log of places you’ve been, whether or not you’ve searched for them? When these amounted to controversy it was forgotten almost immediately.

It doesn’t seem very useful to reassess our ledgers of privacy without also considering our ledgers of power. Those companies that have invited the most criticism for their erosion of privacy have become vastly more powerful than the people doing the complaining. The alleged surplus of “obsessive” worry didn’t do much to stop that; stories like this one, from 1990, which concludes that we have “no way of knowing all the databases that contain information about us” and that “we are losing control over the information about ourselves,” don’t seem pathetic or wrong-minded in retrospect. Mostly just ill-equipped.

In this new world, the old privacy is discarded with for its lack of utility and its interference with ubiquitous and fundamentally incompatible services. In which case this paper is less a guide than a preview of an environment in which today’s privacy concerns seem impossibly minor — and in which their champions are gradually marginalized. It’s an argument, in other words, that may never need to be made, because it will make itself.

The Ballad of the Brooklyn Settler

Back off me

Back off me

Back the fuck off me

Back the fuck off me

Back the fuck off ME

Don’t fucking come back here

I’ll kill you

With one punch

You’re messing with the wrong guy

I fight for a living

You’re messing with the wrong guy

‘scuse you, pal

You push your stroller into people?

Your baby could get hurt

Your baby could get hurt

I fight babies like you, baby

You’re new in the neighborhood

I came to this neighborhood

The only reason white people like you are living here

Is because I settled this fucking neighborhood

For you

Don’t push your stroller into my legs

Don’t push your stroller into my legs

White privilege! White fucking privilege!

You push your stroller right into me

And all I said was, “Excuse you”

And then you said, “Fuck you”

Fuck you!

Fuck you

You white trash

You fucking white trash

Bing & Ruth, "Rails"

Bing & Ruth’s Tomorrow Was the Golden Age was one of the few delights of 2014 — a year widely acknowledged to have sucked as badly as any that had come before it — so it is a great joy to discover that 2015 will see the re-release of City Lake, an earlier effort of limited currency. As this year is currently on target to suck even worse than the previous one, this assuredly counts as a bright spot. Enjoy!

Lawrence Peter Berra, 1925-2015

“Yogi Berra, one of baseball’s greatest catchers and characters, who as a player was a mainstay of 10 Yankee championship teams and as a manager led both the Yankees and Mets to the World Series — but who may be more widely known as an ungainly but lovable cultural figure, inspiring a cartoon character and issuing a seemingly limitless supply of unwittingly witty epigrams known as Yogi-isms — died on Tuesday. He was 90.”

New York City, September 21, 2015

★★★ The morning was chilly enough to give the four-year-old, pried away from his newly filled balloon and hurried out the door without a jacket: another grievance for the litany. The breeze stayed cool after midday; out in the warmth of the sun on Broadway, the gusts were stronger, and soon high clouds helped thin the light. The wind on the avenue was not too much for the balloon on the walk to and from the pre-K pickup. The four-year-old declined to wear the jacket he’d been brought. The sky went over to pale gray, with darker gray fish scales below. In the night, out the open window, people were talking on a balcony quite nearby but unseeable. Up by the ceiling a mosquito perched on the bottom of another balloon, as if the rubber were skin.

A Disruption Cautionary Tale

Bagel-making was still a skilled trade then, restricted to members of the International Beigel Bakers Union, as the name was Romanized after the organization was founded in New York in 1907. (Until well into the 1950s, the minutes of the union’s board meetings were taken down in Yiddish.)

The bagel-maker’s craft was passed down from father to son, fiercely guarded from outsiders’ prying eyes. In a contingency that seemed straight out of Damon Runyon, or perhaps “The Untouchables,” nonunion bakers trying to make and sell bagels risked paying for it with their kneecaps.

“Every bagel that was made in New York City up until the 1960s was a union bagel — every one,” Mr. Goodman said. “The reason why this union was strong was that they were the only ones who knew how to make a proper bagel. And that was the keys to the kingdom.”

The union — New York’s Local 338, with some 300 members — could hold the entire metropolitan area gastronomic hostage and, in disputes with bakery owners over working conditions, often did.

“Bagel Famine Threatens in City,” an alarmed headline in The Times read in 1951, as a strike loomed. (It was followed the next day by the immensely reassuring “Lox Strike Expert Acts to End the Bagel Famine.”)

Then, in the early 1960s, Mr. Thompson’s machine changed the bagel forever.

Daniel Thompson died earlier this month, at the age of ninety-four. His bagel-making machine destroyed the skilled bagel-maker trade and its unions, but it democratized bagel production, allowing the “unsweetened doughnut with rigor mortis” to spread outside of Jewish enclaves — you might say, if you were so inclined, that it’s a classic tale of disruption. But what do we have to show for it? Bagel ubiquity, for sure. But also mediocrity, even in New York City, the cradle of U.S. bagel civilization. The post-artisan bagel is a bulbous tumor of tasteless dough which one must request “toasted” in the hopes that lightly charring it will force some semblance of flavor, any flavor into its lumpen pale mass. New York is so desperate for a decent bagel that one of the most anticipated restaurants of the fall season is hawking undressed bagels for two dollars a piece — seventy-five cents more than one of the current standard bearers of the New York-style bagel. This all just to say that maybe, sometimes, be careful what you disrupt for.

Photo by jill

Patrick Higgins, "Bach: Prelude -- Violin Partita No. 3 BWV 1006"

“Bachanalia emerges from a dynamic relationship among three main elements: Higgins’ own virtuosic classical guitar playing, stereo electronic processing, and the recording spaces themselves. Truly site-specific, it makes unique use of the extreme and special acoustics of St. Cecilia’s Church in Brooklyn and Future-Past Studios, an upstate New York recording complex housed in a historic Lutheran church…. For Bachanalia, Higgins and co-engineer Ben Greenberg worked with a collection of rare vintage Neumann, RCA, and Sennheiser microphones to carefully capture a spatialized natural room reverb. This provided a palate to warp, manipulate, and re-process the sound in precise counterpoint to Bach’s compositions. The end result weaves together live performance and studio composition. The musical arc reaches from light to dark, both in the emotional timbre of the compositions and in the density of the electronic elements.”

— This is terrific. I hope no one on the Internet is as shit-all stupid as to accuse Patrick Higgins of mansplaining Bach.

Aberdeen, Maryland, to New York City, September 20, 2015

★★★★ The glow of dawn, shrugged off in favor of more sleep, did not seem to have been much dimmer than the green glow of late morning through clouds and trees. Outside was clement and cool; the foliage tossed a little but no rain came. The grass or the things growing where the grass used to be made a dry field for wiffleball, sharp grounders bouncing irregularly uphill. A molting blue jay, more mangy gray than blue on top, flew to and from a feeder. Sun came on, and the low, soft plants in the deer-mowed understory of the woods glowed a vivid tennis-ball color. Along the highway, nature’s last greens had begun to burn to back to gold, with flares of incipient red showing now and then. Goldenrod burnished the shoulder. Horses in a field switched their tails. The light was painterly, in an austere photorealist manner. Some cornfields had gone over to a caramel color and others had gone the color of withered corn. Off the Turnpike in Elizabeth, fluffy globes of grasses in various earth tones clung like tribbles to an eroding dirt mound. A man and boy played catch with a football in the empty stretch of parking lot between the Ikea cars and the Toys R Us cars. The low planes seemed even more impossible than usual. The water in the swampy New Jersey approaches to the city was electric blue. The light was generous to container stacks, rusting highway railings, bad brickwork, and other follies of humankind. In the city a frisky breeze was blowing and the sky was smooth shades of lilac and violet.

Let's Sell Some Shit To These Millennials

by Jason Feifer

Welcome, everyone, and thanks for choosing Market 2 Millennials Co. I’m thrilled to be working with you all from Hardwick Sandwich Bags. In front of each seat at this conference table is a cheese sandwich, in a bag, with a name written on it. Please, find yours. And as you do, I just have to say, and I’m speaking from the heart here: You folks make great bags. It was a joy bagging those sandwiches for you. So baggable.

But you have a problem. We conducted a survey for you, and, listen, there’s no easy way to say this, so I’m just going to be upfront: While millennials are Snapchatting, they are ninety-seven percent less likely to be bagging lunch. Less than one tenth of one percent of all tweets are about sandwich bags. Let that sink in. Nobody is tweeting about bags.

This won’t turn itself around. Millennials weren’t raised the way we were, with a passion for sandwich bags. To instill it in them, I’ve developed a customized, four-step plan that I call B.A.G.S. Let’s go through it.

Step “B”: Build The Base! First, we need millennials to understand sandwich bags. We need to make them relevant. The kids, they don’t eat sandwiches. They’ve never seen one. But their iPhone? That fits inside a bag. And the bag is clear. Do you see where I’m going with this? If you were all 24 years old, you would. Kids can take a selfie… with the phone… inside the bag! So fun, right? So we’ll get them started, and have them call it a baggie. They’ll hashtag it: #baggie. All the love millennials have for selfies will be transposed onto bags, and then it’s time for…

Step “A”: Activate! It’s off to the races. Millennials will do literally anything you ask, so long as it involves a catchy hashtag. We’ll tweet out #MyBagBrag, inviting millennials to show off their brand-new bags. We’ve got #FlyTheBagFlag, where a kid ties the corner of a bag to his finger, waves it around and Vines it. And you’ve got to go edgy, of course, so we’ll do #ShagBag, where the kids are encouraged to have sex with a bag. Don’t worry about logistics. They’ll figure it out.

Making you hungry yet? Feel free to open those bags in front of you. God, I love that sound of crinkly plastic.

Step “G”: Galvanize! Once we’ve shown millennials what a bag can do, they’ll need a bag of their own. This generation loathes anything from before 1997. Just look at the briefcase industry — absolutely murdered by millennials. And that’s why it’s critical, right now, that you launch a new line of sandwich bags very explicitly for young people. They need to feel involved. Catered to.

Here’s the rollout: First, we hire YouTube stars to walk into bars in New York and L.A., order beer, and pour it all directly into a bag. But not just any bag: a gold-tinted bag that says SWAG BAG in big, bold letters. All the millennials in the bar will crowd around and Instagram it. Everyone will want to know: What’s this bag, and where can I get it? Great buzz there. And then we announce the product with a big, splashy, sponsored content post on BuzzFeed called 14 Things You Can Put In Bags. By week’s end, millennials will be lining up overnight outside of supermarkets like they’re buying the Apple Watch.

Now the millennials know: Hardwick Sandwich Bags understands them. This Swag Bag is for their swag.

Step “S” is for Surprise! Now we mix things up. Millennials — so entitled, right? Lets harness that. One month after the launch, we halt production of the Swag Bag. The kids will demand it back. We’ll invite a Vice reporter to Hardwick headquarters, and blame the stoppage on the vindictive briefcase industry. That’ll make sense to millennials immediately. Then we seed a grassroots campaign to demand the bags’ return. We’ll drive hard on the hashtags — #BringBackBags, #NeverForget, our most powerful stuff. We’ll offer free Uber rides to anyone who goes to their nearest briefcase store and tweets a #baggie giving the thumbs down. Then we’ll hire the Backstreet Boys to reunite under the name Bagstreet Boys, with a new single called “Bag, Come Back, Baby.”

By this point, bags are the most epic, beloved product on the internet. Adored by millions. You’ll have earned the ultimate reward: everyone tweeting about bags! That’s what we wanted all along. And it’ll last for a good, long time — at least four hours. So we pounce: We announce that Hardwick Sandwich Bags is closing down, but will be relaunching immediately as Hardwickz, which makes Doritos-style chips but in millennial-friendly flavors like coffee, internet, and handcrafted vodka.

Because let’s be honest: Who’s buying bags anymore? It’s a dying business. But millennials sure do love Doritos, so let’s chase that with everything we’ve got.

Image from Prismpak

That'll Do, PM

The spokesman for David Cameron refused to confirm or deny claims that the Prime Minister of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland once stuck his dick in a pig’s mouth.