New York City, September 29, 2015

★★ A layer of visible grime clung to the living room window. The soggy air felt like putting on yesterday’s clothes. Sun coexisted with a thick brown darkness upriver, beyond where a white boat gleamed on the flat water. Which interval of sun would be the last? Rain, rain, rain, said the forecast on the elevator screen. Rain, said the work group chat. Maybe this day’s sunscreen would be the last. The sun was hot and unpleasantly dazzling, while it lasted, and then the darkness and the humidity slammed down harder than before. It was too hot to wear the rain jacket in the absence of rain, but the rain couldn’t be far off. Could it? Uptown was still heavier, still darker. The rain jacket went back in the closet. The air conditioners went on. Finally, a hand stuck out the window got hit by big, falling drops.

The Artisan Chicken Sandwich Eater's Dilemma

In his review of David Chang’s fried chicken joint, which has expanded to two locations within two months of launching, Ryan Sutton notes, for context:

Chang isn’t the only high-end chef to try his hand out in the fine-casual space — the Danny Meyer term for elevated fast food. Del Posto’s Mark Ladner has his gluten-free Pasta Flyer and Brooks Headley has his vegetarian Superiority Burger. Part of the lure is surely the desire to become the next billion dollar empire, the next Shake Shack. And that’s not a bad thing. Why not displace commodity chains in suburban America with more creative and noble-minded institutions? Why not convince entry-level eaters to pay a little bit more for their food, with prices that are higher than Wendy’s yet cheaper than Applebee’s, with meats sourced from humanely raised animals, and with happier employees who (let’s hope) work better better schedules for better pay?

The reasoning behind eating this kind of fast food is seductive: You are not merely choosing to eat an eight-dollar chicken sandwich or a six-dollar hamburger because you have the good taste to fully appreciate why it is a better culinary experience than a three-dollar chicken sandwich or a one-dollar hamburger (and they really are, if you can afford them!), but you are making a moral and ethical choice that is superior to someone who eats a Southern Style Buttermilk Crispy Chicken Sandwich from McDonald’s or a Whopper from Burger King, products of the vast animal protein industrial complex.

Fast food that the affluent can eat while simultaneously absolving their various levels of guilt over eating it — and that can be used to loudly point to their conscientiousness and guiltlessness — allows it to at last be smoothly folded into the grand tradition of the middle class and the rich shaming the poor for making ethically compromised choices: They don’t merely eat too much fast food, polluting their bodies; they’re eating “inhumane” fast food that is harmful to animals and the environment, even though there are now perfectly good and humane and moral and healthy(ish) options are available. This seems like an extreme reading for a values judgment that is largely implicit (for now). But the throughline from Alice Waters admonishing the poor to “make a sacrifice on the cellphone or the third pair of Nike shoes” and Michael Pollan suggesting that, in the context of his dictum to “pay more, eat less,” while “eight dollars for a dozen eggs sounds outrageous,” it’s “really not that much when we think of how we waste money in our lives” is relatively short — particularly when you consider that much of the rhetoric around this type of high-end fast food is grounded in a logic of wide accessibility. (Even though it, by definition, necessitates many of the industrial processes that its progenitors previously shunned, which is perhaps why they’re so insistent on how humane it is, really? Hmm.)

But the ethical quilt of eating an animal that was “humanely raised” (whatever that means!) before your desire to eat a burger got it killed was always threadbare — if you believe thoroughly enough in a pig’s agency to feel that it deserves a good life, and care that it does, why do you still eat bacon? — more completely unravels when placed inside of the capitalist logic of fast-food chains that are designed to scale ad infinitum, because “sustainable meat” simply doesn’t. (Expect many, many more of these Volkswagen-like stories of “humanely raised” meat that it turns out is not really!) Moreover, if the absolution people feel about eating feel-good meat drives people to ultimately consume more of it — because they can afford it! — ecologically it’s a net loss.

This all just to say that it’s okay to eat an eight-dollar chicken sandwich simply because it tastes really good. But don’t mistake the delicious burn in your mouth for the taste of selflessness.

Photo by Momofuku

P.S. if you enjoyed this #content you will perhaps enjoy tomorrow’s episode of the Awl podcast.

Time to Move On

The Times reports on the state of Condé Nast and Time Inc.’s moves downtown:

In the new headquarters, Time’s writers and editors will have to make do with cubicles. The Fortune editor Alan Murray, who is also taking a cubicle, said the number of offices at his magazine is being cut to three, from 43. “I fully understand that some employees are going to miss their big, old offices,” said Joe Ripp, Time Inc.’s chief executive officer. He added that he hoped the new setup will prevent his employees “from writing those interminable three-page memos and walk down the hall and talk to someone.” … “If I found out Fortune’s creative director had an office and we didn’t, that would be a problem to talk about,” Mr. Cagle said. “A lot of nail-biting and hair-pulling is being done by people here.” In a pre-emptive maneuver, he has already joined the Equinox gym in the building, to make sure he has his own locker.

On the bright side, the pre-move layoffs at Time Inc. means that the chances of getting one of those few offices in its headquarters above the unofficial Condé Nast cafeteria are better than one might expect.

Photo by Arturo Pardavila III

Eduardo de la Calle, "I Think I Love You"

The remainder of your days will be darkness and gloom and the vague, poignant memory of a time when things were brighter which will seem ever more difficult to conceive of the further away from it you get. Also it’s gonna rain a bunch. But as soundtracks to deluges go this is pretty solid, so enjoy. [Via]

New York City, September 28, 2015

★★ The crowded, anxious elevator emptied out into a placidly cool and clouded-over morning. For a while the clouds parted, leaving dirty-looking remnants under the bluing sky, but the interval of brightness passed without warming things up. A shower must have occurred during the subway ride, leaving the pavement of Union Square greasy underfoot. Then the gray left and clean white and blue moved overhead. The stone facing of the building was chilly to lean against. Above the warm but clammy streets on the way homeward, the sky was dabbed with new formations of cloud-spots, fresh as paint off the brush of Bob Ross.

Drinking Alone

by Jason Diamond

The last few years have seen no shortage of requiems written for the dive bar, or simply the kind of place that you might pass by without thinking much of it, but feel some sense of loss when you hear it’s closing up — the neighborhood bar, where you can get a can of beer from the American Midwest and a shot of cheap whiskey with little fuss or muss. The types of places that New York Times Magazine “Drink” columnist Rosie Schaap wrote about in her memoir Drinking With Men, are being replaced by specialty beer bars, places with expensive drinks made with cheap ingredients by inexperienced bartenders under the banner of “craft cocktails,” and worst of all, places that never seem to have enough room at the bar.

“Most people want community more than cocktails, and that’s what neighborhood bars offer,” Schaap told me recently. “Great neighborhood bars aren’t an antiquated idea; they’re timeless.” Yet these bars, where you go once a week to see your friends or shoot the shit with the bartender who gives you a buyback after a couple rounds of Jameson, are becoming harder to find. And when you do find one, you just worry about its inevitable demise, or worse, the wrong people discovering it. “The middle-of-the-road places with nice consistent service, the places where you always have a seat, where you can actually hear what the people you came to hang out with are saying, those don’t really seem to exist anymore,” Vicki Lame, a book editor in New York, told me.

Those kinds of bars, the ones with the old neon lights, beat-to-hell seats, and imported beer lists that consist entirely of old bottles of Heineken and Corona, are often wrongly called the “dive bars” by the new neighbors who spend just enough money just carelessly enough for you to know that they have too much. “I’ve seen the term used interchangeably with ‘neighborhood bar,’ which I think is incorrect,” Michael Neff, who has spent a lot of time on both sides of nearly every kind of bar, told me. “Some people call any bar that is dirty or bad or beaten up ‘a dive,’ which is closer but not always the case. If every crappy bar is a dive, then is every dive crappy?”

The East Village bar that Neff and his brother Danny resuscitated this past spring, Holiday Cocktail Lounge, was, for the most part, a place that people called a dive. It isn’t in its new incarnation, but it tries to recreate the look and feel of the old bar. Opened in 1965 and closed in 2009, a few weeks before the eighty-nine-year-old Ukrainian immigrant owner and bartender passed away, Holiday had become thoroughly run down before the renovations. Commenters on the blog EV Grieve began laying odds on what the space would become — 4:1 on a ramen place, fro-yo, or cupcakes; 7:3 “an artisanal joint”; 5:2 another Starbucks, 9:4 another bank; and 11:7 for a 7–11 — but the building’s new owner, Robert Ehrlich, founder of Pirate’s Booty, wanted to keep the bar as close to the way it has been since the mid-sixties, and enlisted the Neff brothers to help him. They cleaned it up a little bit, restored an old mural they found during the renovation that dates back to the thirties (when the space was called the Ali Baba Lounge), and added some food and cocktails to go along with the cocktails, which average around thirteen dollars or so. “We decided to run it like the come-as-you-are, drop-in kind of bar that it has always been,” Neff told me, adding that “people came to the Holiday because they felt like they were part of something, and we wanted that to continue.”

The problem is that a bar on St. Marks place or anywhere around the East Village or Lower East Side can’t be run that way anymore. Anybody is welcome there, and can be a “part of something” so as long as they can afford to pay double, or even triple what drinks used to cost at the original Holiday Cocktail Lounge. One could plausibly argue — and some have — that the new version is a perfect emblem of the exact cultural forces that are eradicating neighborhood bars, one rent-hiked block at a time. In a VQR piece about the self-proclaimed “Best Dive Bar In Los Angeles,” writer Aaron Gilbreath pointed to the King Eddy Saloon, and how the skid row bar that Charles Bukowski and John Fante used to drink in “was starting to market its authenticity, a process which inevitably diminishes authenticity,” and that the bar regulars (“Drug addicts and working class people drink side by side, along with prostitutes, drifters, ex-cons,” and all sorts of other people, according to Gilbreath), were slowly being displaced. Look at reviews of the bar, and the word “hipster” is used more often than not to describe how the bar has ruined itself, catering more to people that celebrate winning the prize “for being DTLA’s most obnoxious friend group.” If that’s the kind of clientele that inhabit the King Eddy now, will people keep wanting to go there? Dive bar chic is one thing, but nothing can seal a bar’s fate like the diminished authenticity Gilbreath wrote about.

Keeping a place that serves drinks open is a difficult task no matter where you do it. As the bartender at my current favorite local bar, Sharlene’s on Flatbush in Brooklyn, told me, “You need to get at least half a million to open a bar in New York anymore. You need investors and shit,” before launching into the laundry list of organizations trying to shut you down, from churches that he said he’s seen petition to get new bars from getting a liquor license, to the health department and other local officials with power to wield. I learned this at my first real neighborhood spot as an almost-adult, which was also my first introduction to just how hard it is for bar owners to stay open. I never learned the place’s name because it didn’t have a sign on the door, and Googling “Logan Square bar closed 2000” doesn’t help much. What I do remember was there were maybe seven bottles of liquor on display, they served Budweiser, Bud Light and Old Style, and Heineken was the most expensive thing on the menu.

The old lady that ran the bar once told me that when she moved from Germany to Chicago and settled in the neighborhood that she learned Polish before English so she could talk with her customers. A few days after a December blizzard that dumped over a foot of snow on the area, my stir-crazy roommates and I braved the snow and walked to the bar, only to find a “closing party,” and all the bottles of booze they had in the house were on sale for whatever they paid the distributor for them (I bought two bottles of root beer Schnapps for ten dollars and a bottle of vodka from Poland for four). I asked why they were shutting down since the place was always filled with loyal customers, the lady told me in her jumbled German/Eastern European/Great Lakes English accent, “The powers that be don’t want any more bars like this.”

The bar was another victim of Mayor Richard M. Daley’s reign, during which he ruled the city with the same “puritanical streak” as his father — outlined by Whet Moser in his 2012 Chicago magazine piece, “The Decline of the Chicago Neighborhood Tavern: A Daley and Demographic Legacy.” Long before Chicago’s various neighborhoods like Logan Square began being touted as “upscale” and “trendy” by realtors, a thousand liquor licenses, some dating back more than sixty years, were revoked between 1990 and 2005, the second Mayor Daley believing, just like his father before him had, that local taverns are a blight for neighborhoods and needed to be phased out.

In New York City, not surprisingly, it’s the property owners who are doing the most damage. Hogs and Heifers, the biker bar that opened in the then-unsavory Meatpacking District in 1992, closed this past August after the owners wanted to raise the bar’s rent to sixty thousand dollars a month to stay located in the spot that is now an iPhone 6S Plus’s throw from an Apple Store. Other places, like Trash Bar on a stretch of Williamsburg that didn’t have a movie theatre or fancy resturaunts on it when it opened in the early aughts, closed after their lanlords reportedly wanted to jack the rent up by four hundred percent. In the ideal version of this scenario, it makes way for spots with small batch whiskey and nine-dollar IPAs from craft breweries like Evil Twin to go along with charcuterie plates and oysters, even if not everybody wants those things. The other option is that the place gets converted into a bank or the building is knocked down to make way for more condos.

Artist John Tebeau, whose collection of illustrations of New York City’s greatest bars throughout the ages, Great Good Places of New York, is set to be released by Rizzoli next year, tries to see both sides of things. “It might be a new golden age for truly great bars, who knows,” he ponders after I ask him his thoughts on the vanishing neighborhood bar. His reasoning is simple enough, “I like plenty of the newer ones. Sure, they’re not ‘classics’ yet, but a lot of them are damn solid and will become or have already become neighborhood mainstays.” He mentions Fort Defiance in Red Hook, Brooklyn, recalling that owner St. John Frizell “wanted a “great good place” in his neighborhood, “so he opened his own in 2009, and Red Hook wins.” Red Hook, one of the most cut-off Brooklyn neighborhoods considering its lack of subway stops, isn’t exactly the Pale of the Settlement (there’s an IKEA and a Fairway grocery store there, along with a number of great little local businesses that are surviving alongside the newer crop of restaurants and bars that are moving out there), but it’s essentially a last refuge for bar owners like St. John Frizell.

Maybe Tebeau is right. The rush to over-populate our big cities will probably have to taper off at some point. Those new bars will someday be old bars, those that are left having survived the test of time and escalating rents. Maybe there’s hope that the neighborhood bar, the one with the bartender that offers buybacks and the broken-in seat you live, can make a comeback. Or not.

Photo by j. lindsay

Startup Idea: ReHome

by Your Future Cofounder

Airbnb. Amazing. Airbnb “believes that people can and should feel like they belong anywhere in the world.” Strongly agree. Hundreds of thousands of hosts. Tens of millions of users. 500,000 stays a night. A re-imagination of the notion of property. Incredible.

However, Airbnb investor Sam Altman says:

Unfortunately, a lot of other people have problems paying their rent or mortgage.

That’s bad. But:

75% of Airbnb hosts in San Francisco say that their income from Airbnb helps them stay in their homes, and 60% of the Airbnb income goes to rent/mortgage and other housing expenses.

That’s good! So why not let Airbnb help them even more. That’s where ReHome comes in.

Startup idea: ReHome will let renters and homeowners spend as little time in their homes as is necessary to keep them. By providing affordable sleep-work-live arrangements in extremely space-optimized towers located at or near public transit termini, ReHomes allow sharing economy rentrepreneurs to lease a bed in a beautifully efficient open-plan space. (The spaces could be inside of used shipping containers or former public housing, or even former disrupted office and residential buildings — ReHousing isn’t about the specific space, right, it’s an IRL API for the opportunities inside of it.)

Right, so your stay will be all-inclusive: A mattress (Casper Lite Coil Spring), collaborative bathrooms, and Wi-Fi in cases where cellular service is not available in this part of town. Since these towers may be outside affordable delivery zones, so ReHome, in partnership with Soylent and Beyond Food (formerly Beyond Meat), will offer consumption plans.

This is just a pitch. First things first, right, so we’ll use existing home-havers to scale ReHome. But this idea has real potential. At scale, ReHome could offer financing to partners in order to lease or purchase properties. These deals would be revolutionary: priced not only in dollars but in time. Right so ReHome could finance your home on a set monthly payment plan. $4000 a month with zero days shared could be reduced to $3000 a month with five days shared. ReHome could take care of the rental — either through future partners Airbnb or a future rental service of our own. ReHome would not own these properties it rents or finances, right. So that would be handled by an unbundled partner company called ReBank.*

ReHome will provide an app to help you determine your best home/ReHome living balance. Whether you need to stay in a ReHome for one day a week to make rent, or six days a week to make your mortgage, ReHome’s on-demand real-time pricing model has an option for you. Not yet broken into the personal shelter market? A ReHome is a great way to incubate your dream of renting a home near a population center, where you can enjoy the fruits of the Logistics and Leisure Revolution, such as solid food, and then renting that home to inspiring influencers from other cities.**

ReHomes are ultimately about community. Right? So you can Network with fellow free-working rentrepreneurs to get an edge over fellow Taskrabbit, Uber and Amazon Flex partners via sharing learnings.***

ReHome would also offer to its partners a rewards program. Helping to clean the ReHome space, or shuttling ReHome parters from their homes to their ReHomes, can earn you extra free nights. Save up enough free nights and you can redeem them for an extra night in your own home, credited as a client night. Right. So.

Anyway. Let me know. I’m searching for investors and a co-founder. I’m more of an ideas guy so I need someone good with computers.

*Not an FDIC bank

**ReHome Partners are not “guests” and their co-sleeping are not spaces “rooms.” Each cubicle area gate is compatible with industry-leading padlocks.

***Formal labor organization is counter to the spirit of ReHome and is not allowed on ReHome-licensed premises

How Much Do You Bring to the Table, Content Human?

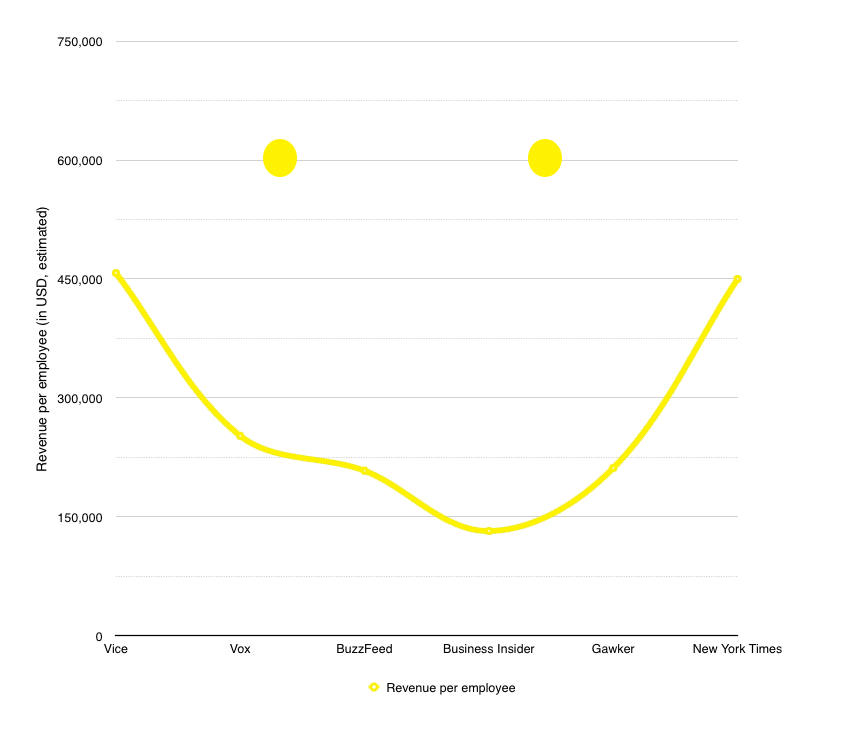

The German publisher Axel Springer DE is purchasing 88 percent of Henry Blodget’s extremely popular travel blog, Business Insider, for 343 million dollars in cash; its stake is valued at 390 million dollars. (The total value of the company is pegged at 442 million dollars — Axel Springer already owned nine percent, and Jeff Bezos is not giving up his shares.) The number that Axel Springer and Business Insider want you to consider is 76 million unique visitors per month, but the future is in distribution, not unique visitors anymore, so let’s talk money!

According to Peter Kafka, that number is nine times this year’s projected revenues, which appear to amount to just over 43 million dollars. (It is six times next year’s projected revenues, so BI is expecting to make 65 million dollars next year, or a roughly 50 percent jump.) BI employs 325 people (half journalists, it would like me to tell you!), meaning it currently brings in roughly $132,300 in revenue per employee.

To compare, BuzzFeed is valued at a 1.5 billion dollars, and has projected revenues of 250 million dollars this year. With more than a thousand employees — but let’s say 1200 because they’ve probably hired twenty people in the time since I started writing this? — that’s revenue of over $208,333 per employee. (Already up $60,000 per employee since January.) Gawker has around 260 employees. Last year’s revenues were 45 million dollars; let’s say it’ll make 55 million dollars this year, based mostly on projected growth in Gawker’s affiliate revenue. That’s a little over $211,538 per employee. Vox Media, which is now valued at just over a billion dollars*, had projected revenues this year of roughly 126 million dollars, according to the Wall Street Journal (albeit in January, when Vox was valued at less than half of what it is now); according to the best available public numbers, it has somewhere north of 400 employees, but let’s say 500 for the hell of it? That would amount to around $252,000 in revenue per employee.

And then there’s Vice, which is projected to make 915 million dollars in revenue this year; as of March, it had 1500 employees. Let’s be crazy and say it has 2000 right now — even at that number, it would be generating more than $457,500 per employee. (In case you were wondering why Vice is worth all those billions and the other internet companies that it is often compared to aren’t!)

But, for what it’s worth: The New York Times Company, which has only been profitable through cost cutting in recent years, generates somewhere between $440,000 and $450,000 per employee; Time Inc., which has been slash and burning through jobs for years now, brings in $417,000 employee.

(P.S. A lot of these numbers are closely guarded or extremely fuzzy, so if you have insider knowledge and would like to correct any of them with more current information, please let us know. 😉

* This post previously used Vox’s pre-money valuation of 850 million dollars. An apparently important thing to note when throwing around investment-pegged valuations is whether it’s pre-money or post-money. 🙂

Television Rx: What to Watch If You're in a Mood

by Logan Sachon

This post is brought to you by Hulu. Sit back and catch up on all your favorite shows on Hulu.com!

Humans are moody. It’s one of our perks. Some moods call for a quiet walk in the park, some for a run around the block, and some for plopping yourself in front of a screen and watching fictional characters do fictional things in fictional worlds. Your moods, our prescriptions.

If you are feeling:

Frustrated because you’ve had to interact with a man; exasperated because of the existence of men; ashamed that you are man.

Then you should watch:

The Mindy Project

The Mindy Project won’t cure your misandry (nothing will), but it will at least make you feel better about men, or rather, one man, for the duration of your viewing experience. To be clear, men do suck, but Dr. Danny Costellano (Chris Messina) does not, and spending half-an-hour with him while he pals around with/woos/dates/impregnates/loves our girl Dr. Mindy Lahiri will remind you that there are some outliers with an XY chromosome. Men, you could be Danny Costellano. Women, you could date/befriend/raise/pass on the street/be ignored on Twitter by Danny Costellano. Dreams can come true, at least on TV.

If you are feeling:

Divorced from the people; snobby; superior; classist; like you’re hiding in your white tower; like you just referred to half the nation as flyover country; like you looked at some recent poll numbers and were like, wait, but everyone I know is in their 20s or 30s and liberal so I don’t know how any of these stats could possibly be right???!??!?!

Then you should watch:

Modern Family

Modern Family has won five Emmys for best comedy series, more than any show you’ve ever loved (or pretended to love). People love this show! But you don’t love this show. You haven’t seen an episode of this show. You’ve probably made fun of this show, rolled your eyes at this show, balked when this show’s name was called on a Sundaynight while you were livetweeting an awards broadcast. Change that. Because here is what will happen if you watch an episode of Modern Family: You will laugh. You will cry! You will feel emotions that millions of people across the country have felt, as they have watched the same quips and moments. You will understand America. You will understand yourself.

If you are feeling:

Superficial; mean; petty; annoyed with everyone; caustic; sardonic; slightly evil; a little bit sinister.

Then you should watch:

Difficult People

Hey guess what. You’re not a bad person. Julie and Billy are bad people. Enjoy their badness and compare it your badness and feel a little lighter. Their badness is funnier than your badness; you are not that funny, so it’s not all sunshine and roses for you. But you’re not that bad. You are fine.

If you are feeling:

Listless; bored; like you need a new hobby; a new raison d’être; something to think on, obsess about, dream about

Then you should watch:

Nashville

Here’s the thing about Nashville: It’s great. It has characters you love, and characters you hate, and characters you start out hating, and then love, and then some you start out loving, and then hate, and couples you ship, and then couples you want to never be in the same scene again. It’s a lot! It’s a lot of fun! And there’s singing. Never enough, but some. You’ll want to buy a guitar. You’ll want to move to Nashville. You’ll want to make a pilgrimage to the Blue Bird Café. Maybe you’ll do all of those things. Maybe you’ll do them because of Nashville.

If you are feeling:

Good about the world; safe in your body as a women; that your women friends and lovers are safe in their bodies; that you can walk home alone at night, no problem; that your taxi cab driver isn’t about to take you away never to be seen again; that your friend’s failure to respond to your text doesn’t means she’s dead in a ditch

Then you should watch:

Law & Order: SVU

A gentle reminder, in a predictable and familiar format, that life can always be, and often is, less than comfortable (especially for women). And don’t you forget it!

If you are feeling:

Like committing the perfect crime.

Then you should watch:

CSI

This show will scare that seed of a perfect-crime idea right out of you. The supreme lesson of CSI:

you’re gonna get caught.

GIFs: Perfect Gif