New York City, October 21, 2015

★★★ The late-rising sun rose later than the late-rising people, and the dimness made it seem as if it must be overcast: the first and most blatant point of confusion on the day. Haze softened the landscape even as it brought a harsh glare to the sky. The warmth was wrong for the angle of the sun, or vice versa, and somewhere under that warmth there was still an uneasy chill. Nobody could agree on how to dress; the light was cinematic but the people on the sidewalks looked like mismatched extras. Downtown was whitened, but uptown and both ways crosstown the glimpses of distance were stained brown.

Palate Fatigue

The other day, in its weekly run of food stories, the New York Times printed a pair of pieces that, while about different topics — one an incisive assessment of the shortage of rank-and-file cooks that serve as the foundation of every kitchen in restaurant industry, the other a review of a highly anticipated and incredibly hyped pizzeria in the East Village — ultimately both point toward a similar conclusion: Maybe the food in the most talked-about restaurants has been less good lately?

Of the effects of the junior-level cook shortage — driven by, among other things, the profession’s infamously cruel wages in exchange for anonymous, grueling labor at a time when a teen can open his own restaurant and charge a hundred and sixty dollars a head — Julia Moskin writes:

For some, it has even affected their food, forcing them to simplify dishes, to focus on basic, scalable restaurant concepts like pizza or burgers, and to hire virtually anyone who walks through the kitchen door. “I have given up expecting that every single one of my line cooks will be able to season correctly or understand heat,” said Hooni Kim, who owns Danji and Hanjan in Manhattan, where he has added dishes that he can cook himself, in advance, so that his line cooks need only heat and serve. … For diners, this gap between what the chef wants to do and what the cooks can execute explains why many new places offer dazzling menus but disappointing food.

And of Bruno, a pizzeria opened by a pair of acclaimed young chefs in July, whose high-concept dough is impossible to ignore, and whose bread appetizer won breathless adoration from people fortunate enough to try it, Times restaurant critic Pete Wells writes, in a rare zero-star review:

Bruno has a few problems. It’s only been open since July, so maybe it will work them out eventually. I hope so. I don’t want to convict the restaurant’s chefs and owner for these problems because the real killer, as O. J. Simpson would say, is other people. More accurately, it’s a small group of people like me whose approval can lift some restaurants from the teeming primordial swamp of contenders, and whose premature praise and willingness to play down discomfort and inconvenience enable problems like Bruno’s. … Bruno is one of many new places where building flavor seems less important than composing an image that can rocket straight to the digital billboards. It’s hard to explain how great something tastes, but easy to show how great it looks, and in the short run, contemporary food media rewards the latter.

So, these are just two pieces, and they’re talking about a relatively small set of restaurants, but there definitely seems to be something happening in the New York restaurant scene writ large in recent months to the effect that things feel… off? Some informal polling of several people who go to restaurants professionally (or close enough!!!) or work in food revealed that while one person, a critic, disagreed vehemently, everyone else I talked to also felt like things are, like, kind of blah out there; another critic remarked that there’s a lot of “spiritless execution” happening right now.

This is maybe partly due to growing numbers of lesser line cooks and dishes that are not so much cooked as they are designed. But it’s hard not to suspect as well a growing, if nascent, fatigue with the current restaurant scene, inflicted by the vast sameness of capital-f Food Culture — — not of dishes or cuisines or flavors, but of sensibility — and its bounty of eight-dollar ethical fried chicken sandwiches, chef-driven chains, classic cocktails with a twist, nigh-infinite grain bowls, and cultured butter for the bread portion in tonight’s Nordic-inspired, five- or seven- or ten-course tasting menu and the attending machinery powering its expansion in recent months and years.

Maybe what’s being detected here is a temporary funk in the restaurant scene, or like a particularly lame moment before something truly incredible happens. Or maybe it is the beginning of a widespread palate fatigue, the collective sense of taste of the restaurant-going crowd finally beaten into grim, mostly comfortable numbness. But also like, no one on Instagram actually cares how anything tastes.

That Hot New British Band Actually Happened A Decade Ago

“Ten years ago, on 23 October 2005, Arctic Monkeys’ debut single I Bet You Look Good on the Dancefloor went straight in at No 1…. The band’s novel internet-spawned success was reported on the national news. They weren’t fussed, according to their then-PR manager Anton Brookes, but it was genuinely significant for the music industry, which was moving into a more stable era following the lawlessness of Napster at the turn of the century. In June 2004, iTunes had launched in the UK, and downloads went on to account for 17.9% of that year’s singles chart. (Digital sales weren’t even tracked in 2003.) By 2005, that number had more than doubled to 36.6%. Singles were regaining vitality, and Arctic Monkeys proved that giving away music for free wasn’t career suicide, but a smart move.”

— Holy fuck am I old.

The Selling of Stuy Town

by Brendan O’Connor

On Tuesday, the Blackstone Group, a colossal investment firm based in New York, and Ivanhoé Cambridge, the part of Quebec’s public pension fund manager that invests in real estate, signed a contract to pay around 5.4 billion dollars for Manhattan’s largest apartment complex, the long-disputed Stuyvesant Town-Peter Cooper Village, which sits on the east side of the island, between 14th and 23rd Streets. As part of the deal, Blackstone and Ivanhoé committed to rents that would keep forty-five hundred apartments — forty-five percent of the total — affordable to middle-class families (as defined by the federal government), and five hundred apartments affordable to low-income families, for the next twenty years. In return, the New York Times reported, the de Blasio administration gave Blackstone a hundred-and-forty-four-million-dollar low-interest loan through the Housing Development Corporation and waived seventy-seven million dollars in mortgage recording taxes. (Although, they’ll still have to pay a hundred and sixty million dollars in transfer taxes.) Blackstone also agreed not to convert the apartments into condos or to build any new towers.

Stuy Town was ushered into existence by Robert Moses in 1947, intended largely for returning veterans and their families — imagined as a middle-class oasis set in Manhattan, the product of an era when civic-minded people did things for the city and its residents because they were right, not because they were profitable. But it is also built on the ruins of the Gas House District, which Moses had bulldozed, displacing eleven thousand residents, and it was segregated until the sixties. The Gas House District was a diverse, working-class, neighborhood filled with light industrial businesses — the kind of place Moses considered a slum. A New York Times story from 1946 marks the occasion of the older neighborhood’s last resident being evicted: “Mrs. Mary Plotkin looked out the window of her stationery store at 444 East Fourteenth Street yesterday and scanned a scene of desolation. A dismal rain dimmed the vista of wrecked buildings and hills of debris. Workmen moved forlornly about, adding to the seemingly chaotic effect.”

Tuesday’s deal is being celebrated by the de Blasio administration and its allies as a big win. City councilman Daniel Garodnick, a lifelong Stuy Town resident, lent his support. “This deal achieves our core goals of preserving the community as a stable home for New Yorkers today and into the future,” he said. “This time, the buyer not only has a more patient and stable investment structure, but goes to great lengths to preserve long-term affordability,” he continued, referring to Tishman Speyer and BlackRock’s disastrous 2006 joint acquisition of the housing complex that led to the investors defaulting on 4.4 billion dollars of debt in 2010. “This has been a priority for us since Day 1,” the mayor said in a statement Monday. “We weren’t going to lose Stuy Town on our watch.”

According to the Times, the Blackstone Group manages ninety-three billion dollars worth of real estate in the form of hotels, warehouses, and office and residential space worldwide. The company “routinely” gets eighteen percent returns on its more opportunistic, speculative investments, which is pretty good. But the company is expanding into longer-term deals, having raised a 15.8-billion-dollar real estate investment fund in March — reportedly the largest in the world. Last month, for six hundred and ninety million dollars, Blackstone bought twenty-four market-rate rental buildings in Chelsea and the Upper West Side.

The Blackstone Group is buying Stuy Town through Blackstone Property Partners, the Real Deal reports, which is a fund it launched in July 2014, raising around six billion dollars in equity, largely from pension funds, to pursue investments with longer holding periods. (“I think the important thing to note here is the kind of capital we’re using,” Blackstone’s Global Head of Real Estate Jonathan Gray said. It sure is!) From TRD:

For Blackstone, the push into core real estate is an attempt to address a dilemma faced by all private real estate funds: it’s never been easier to raise capital, but with more players gunning for deals it’s become harder to deliver high returns. Some funds are tackling this issue by entering new markets or structuring creative deals. Others, like Blackstone, are embracing lower returns on some deals. “The core-plus asset class is about three times the size of what we’re doing in the opportunity class,” Blackstone’s co-founder and CEO Steven Schwarzman said in an earnings call last year, adding that the company could well add $100 billion worth of core-plus assets within the decade.

Ivanhoé Cambridge, meanwhile, has invested more than five billion dollars in Manhattan real estate over the past five years, the Real Deal reports, more than any other pension fund manager — and even more than real estate companies like Related, Brookfield Properties, or American Realty Capital. In February, the Montreal-based company acquired 3 Bryant Park for 2.2 billion dollars. Apparently, no one from Ivanhoé was present at the formal announcement of the contract’s signing on Tuesday — despite having invested, at 1.3 billion dollars, half of the equity in the Stuy Town deal (and possibly even more, really, given that it says it’s invested in every Blackstone real estate fund). Not to worry, though: “We love New York and have loved it for a long time,” Ivanhoé Cambridge’s executive vice president and chief global investment officer, Sylvain Fortier, told the Real Deal.

When Rob Speyer led his ill-considered bid to acquire Stuy Town in 2006, he not only failed to anticipate the global economy’s imminent implosion but also the hostility older tenants would have to their buildings being converted to market-rate housing for finance and marketing yuppies. In 2012, CWCapital, which came to control the property after Tishman Speyer defaulted on its loans, agreed to settle a class-action lawsuit filed by Stuy Town residents over illegal rent deregulation for 68.7 million dollars in damages. “Stuy Town is the quintessential rent-stabilized apartment filled with well-educated old Jews, and you shouldn’t fuck with them,” one affordable-housing advocate had earlier told New York magazine. “What the hell were these guys thinking?”

After the plans for Stuy Town were announced in 1943, one study estimated that no more than three percent of the people living in the Gas House District would be able to afford the proposed rents for the new development. More than half of Stuy Town’s apartments already lease at market rates — more than forty-two hundred dollars per month for a two-bedroom, the Times reports, and Blackstone will be able to bring another twelve hundred apartments up to market-rate rents in 2020: It’s only a matter of time before the rest can be brought to market rates as well. “This is the type of asset we want to own for a long time,” one Blackstone senior managing director said. “This is a long-term hold,” added Fortier. “We’re not looking to flip it and make a quick buck.” How long is twenty years, anyway?

Photo by Marianne O’Leary

Reminders Everywhere

This piece by Awl pal Matthew J.X. Malady about the unexpected complications that technology adds to the grieving process is very worth your time, but perhaps should be read in a place where you can express emotion freely if necessary.

A Poem by Mairead Small Staid

by Mark Bibbins, Editor

A Wrestler’s Book of Saints

(i)

Track any madness back: it grows holy.

My sister holds a lighter to the pale,

thickened soles of her feet, but Columba —

transcribing the Bible as invaders

swarmed the abbey walls — ran out of candles.

He found fresh wax in his left hand, lighting

each finger from the embers of the last.

What is the body but a body, you

might say. My sister knows better than that.

What is the body but a carnival

ride? What is the body but a long fall

or dive? If the soul is all that counts, why

sever hands & fingers, feet? Why keep them

precious in the reliquary, why kneel?

(ii)

Precious, in the reliquary, we kneel.

Track any madness back: it grows holy.

My sister breaks open holes in her hands,

but Francis bore stigmata too — the word

from the Greek, to mark. What is the body

but an ornament? What is the body

but a prize? At carnivals & wrestling

matches, a mark is a target, a fan,

someone who doesn’t know it’s fake. Or if

he understands that much, he doesn’t know

it’s also real. The wrestlers hide razor

blades in their wristbands, on their fingertips,

to open their own foreheads when they’re hit.

Blood pours from every homemade crown of thorns.

(iii)

Blood pours from every homemade crown of thorns,

seeps between bared & grinning teeth, but hey:

track any madness back, it grows holy.

The glow behind Columba’s head is his

own hand, alight. Who says we cannot make

ourselves into saints? The wrestlers are split

into parts: a heel, a face. The face stomps

the heel — these words grow strange in the ring, mean

other things; these parts are magnified, made

into wholes. What is the body but an

assortment? What is the body but shorn?

The wrestler grows his shining hair as long

as Samson’s was, before. Every strand is

oiled, as if he has just been baptized.

(iv)

Oiled — as if he has just been baptized —

the wrestler has communion in a match.

Slap a match to oil & you get flame;

track any madness back, it grows holy.

We eat the broken body of a god —

does that make us cannibal? Only if

we, too, are gods. Only if we, too, can

take a hundred hits & bounce back up. What

is the body but an icon, a show?

The wrestler slaps a man to kingdom come.

This is the miracle: he is beaten

to death, yet lives. Is killed, yet rises three

days later, thousands screaming his return.

We drink his blood, still warm. We wear his shirt.

(v)

We drink his blood, still warm. We wear his shirt,

the one he tugs off tenderly, a man

born to show the world his scars, their shining.

This is awe-some, the crowd chants, but if you

track any madness back, it grows holy.

My sister shuts her mouth & locks it tight,

but Catherine starved herself as well, food just

a distraction from the impossible

theology of bones growing below

her skin. The wrestler’s ribs glimmer between

his muscles. Stretched like putty, he puts us

together. The ring collapses, slanting,

pouring men on the concrete floor. This world:

it’s full of unnatural disaster.

(vi)

It’s full of unnatural disaster,

the wrestling ring: tables smash to pieces,

chairs twist until their metal seems transformed.

Their old purpose, transubstantiated.

This is dinner gone wrong, the self the meal.

Track any madness back: it grows holy:

even Jacob laced up boots to wrestle

an enemy, angel or God. He fought

to a draw & was blessed. His hip wrenched from

its socket & yet. What is a limp next

to fame like this? Forget Jacob, a name

adjacent to the Hebrew word for heel.

He is given a stage name: Israel.

He is given a role to play, a face.

(vii)

He is given a role to play, a face,

the wrestler who holds fire in his hands

& is not singed. He wears the barbed wire

like a halo. What does a man become,

when he can suffer so much, & thrive? He

is either a god or has his backing —

track any madness back, it grows holy.

He is the patron saint of pain, of roar,

of strength made weak & raised to rage again,

of muscles buffed to shine until you see

yourself in them. You see yourself in him.

What is the body, after all, but a

mirror, but a glass? Filled to the rim &

brimming over. Spilling onto the mat.

(viii)

Brimming over, spilling onto the mat,

this tide is dark as garnets, deep & wide

as Jordan — says my sister — once upon

a time. I am the only mark for this

display of skin & bones, of blood that could

easily be my own. The body is

nothing but a punishment, a penance.

Track any madness back: it grows holy.

My sister presses her hands to her throat

& passes out, but Saint Teresa swooned

every day. She prayed to be made ill, as

if by suffering, she might serve. Who can

say? Everyone loves a comeback, the stone

rolled away. The body felled, arisen.

(ix)

Rolled away, the body felled, arisen,

seems to shine. The wrestler howls. My sister

peels the scabbed flats of her wrists & hands. She

flicks her skin away as if it is not

sacred, each cell a relic to be kept.

She doesn’t care what’s left behind. What is

the body but an urge to be beaten

out? A myth, that wounds give off their own light.

Track any madness back: it grows holy.

Fresh welts rise on the wrestler’s back like bread,

leaven, & blood teases below his skin,

a river of symbol, of sustenance

to be uncorked, drunk down. The crowd calls Oh

my God — but He does not acknowledge them.

(x)

My god — but he does not acknowledge them,

busied with wrecking worlds, a carpenter

in reverse. Christ himself flipped the tables

at the temple — talk about a heel turn.

This worship of bodies is nothing new,

this roar for the same bodies to be wrecked.

Between reverence & revulsion lies

a line as fine as cilia, fine as

flagella, fine as dust of bones ground down.

Track any madness back — it grows holy —

but we balk at the brain kept in the jar.

Good God Almighty, the old announcer

cries, & we stand to see who has returned,

is risen to forgive our every sin.

(xi)

He rises to forgive our every sin,

rises to the first rope & the second

& the top. Climbs ladders & the chain-linked

sides of cages, seeks greater heights like heat.

What is the body — I have not forgot —

but a story? Saints called shed former selves

like flesh. They fit in the skin they’re given,

the skin we stitch together as we watch.

We want — & then we call his famous name,

but he, shape shifter, has abandoned it.

Track any madness back: it grows holy.

Joseph of Cupertino also flew,

rose to the stone roof of his cell & left

his weighted & unsainted past below.

(xii)

His weighted & unsainted past below,

the wrestler clambers to the cage’s top.

Ho-ly shit, the crowd chants, but what isn’t

holy in this light? From parts unknown the

wrestler comes, from parts unknown he is pieced

together: a face, a heel, an eyeball

gouged out & dangling. The wrestler loses

a tooth in his matted beard. His forehead

is a desert, paths tracked into its sand.

He leans & teeters: Ho-ly shit, we breathe,

we scream, Ho-ly shit, as the wrestler falls.

Track any madness back: it grows holy,

heaven, plummeting. What is the body

if not a song? Holy, holy, holy.

(xiii)

If not a song — holy, holy, holy —

what is this repetition but a cure?

(This compulsion is madness too, you know.)

The wrestler scatters tacks across the mat,

but Saint Sebastian lived through a thousand

arrows. In the ring, all destruction is

self-destruction. Thou shall not harm any

other — unless it is asked for, begged for,

only way to grant his wish. The wrestler

dies, by the way. This story doesn’t end

well. One plunge too many, one push too far:

the way any saint becomes a martyr.

Track any madness back: it grows, holy.

What else is this body, if not a prayer?

(xiv)

What else is this body, if not a prayer?

I’m running out of possibilities.

If the wrestlers are angels, saints, or gods,

then what does that make us, who cheer to see

them tormented? What are we, followers

or Pharisees? Believers or jeering

masses? Are we ourselves the gods they want

the blessing of? I can’t keep track. I don’t

know where my sister went. I don’t know who

she is. My focus slips like sweating skin

through palms, like blood through busted-open veins,

but I recall these words, a small comfort —

I must have heard them somewhere, long ago —

track any madness back, it grows holy.

(xv)

Track any madness back: it grows holy,

precious, in the reliquary. We kneel.

Blood pours from every homemade crown of thorns.

Oiled — as if we have just been baptized —

we drink his blood, still warm. We wear his shirt.

It’s full of unnatural disaster,

the role he is given to play, the face:

brimming over, spilling onto the mat,

rolled away. The body felled, arisen —

my god — but he does not acknowledge us.

He rises to forgive our every sin,

his weighted & unsainted past below.

If not a song — holy, holy, holy —

what else is this body, if not a prayer?

Mairead Small Staid’s poems, essays, and articles have been published in AGNI, the Believer, Narrative, Ninth Letter, and Ploughshares, as well as online at The Hairpin, Jezebel, and The Point. She is a graduate of the Helen Zell Writers’ Program at the University of Michigan and a MacDowell Fellow.

You will find more poems here. You may contact the editor at poems@theawl.com.

Some Thoughts About Constant Connectivity

I don’t have a smartphone. I am aware that this puts me in an ever-shrinking demographic (when I got my most recent phone, a model so simple that its most advanced feature is a slide-out keyboard, the person helping me called over two of her co-workers because none of them had seen it before), and there are certainly annoyances I put up with to maintain that status: When I’m heading somewhere unfamiliar I have to plan my journey out in advance. I always need to remind people that if they’re going to be late or they need to cancel plans they have to text me because I can’t get email. I spend a lot of time standing on line thinking about things instead of calming myself with crushable candy or whatever. (This is perhaps the hardest part of refusing to enter our mobile world; there is almost no one who needs protection from being alone with his thoughts more than I do.) And yet I persist, because I refuse to become a hostage to the web. I refuse to be always available. I refuse to forget that most of life is boredom and discomfort with no easy recourse to distraction.

I have no illusion that my refusals are in any way reflective of a growing movement against constant connection. If anything, it’s only going further the other way. For example: Do people in Silicon Valley ever turn off their phones? The answer seems to be an occasional, semi-braggy “yes, but only when I’m running marathons,” which is overshadowed by an overwhelming “no, not really, not by choice,” or, as one person actually put it, “We’re building a company for the long term and being offline is not an option.” “I do sleep with my phone under my pillow, though!” says a woman who prides herself on carving out two-to-four hours “away from device-enabled connectivity.”

I get it. I understand that once you have the technology it is almost impossible not to use it, even if you know it is ultimately bad for you. I am aware that making yourself constantly available — creating a world, in fact, where being unavailable is not an option — is a way to signal how busy and vital and valuable you are. If your self-esteem is completely wrapped up in the idea that “online” equals “working” and “working” is how you demonstrate your level of importance, the idea that you might miss an email is horrifying, because it robs you of your carefully-constructed concept of yourself as a dynamic, important part of the digital age.

And then there’s this: “I can come up with a long list of reasons why you should be a lot more worried about people who are on their phones than people who are off them. But culture is a weird thing. Sometimes we want to be pure and above it all, to be observational. Other times we want to fit in. At that moment, in that bar, anyone not looking at their phone was presumed to be a serial killer. So I took mine out of my pocket and looked at it, and everyone else chilled out.”

I realize that I am swimming against the tide of history here. But if I can ask a question that we may have overlooked in our rush to take advantage of everything that’s available to us in this new world, WHAT THE HELL IS WRONG WITH YOU PEOPLE? Not only are you normalizing psychotic behavior, you are stigmatizing basic human interaction. (And if you think that “psychotic behavior” is a tad harsh as a descriptor for smartphone usage you should Google up the symptoms of that condition the next time you wake up at 3 A.M. and reach for your device under your pillow.) You are trying to tell the rest of us that being gross in the way you are gross is actually admirable and something one should aspire to. You are encouraging the worst kind of narcissism and you are pretending that it is progress. You are pretending that it is acceptable.

Look, if you guys want to become glass-eyed scroll jockeys I am not going to stand in your way, but when you try to turn things around so that not being on your phone every second somehow makes you the freak then things have gone too far. I know you are reading this on your phone right now and shaking your head, but let me tell you something: YOU ARE THE REAL FREAK. Unless you are a doctor and a patient might die there is no more need for you to be available all the time than there is for a teenaged salesperson in a retail apparel store to walk around with a headset. That’s who you are, you hollow-faced tap-addict: You’re a Gap employee circa 1999. Put down your fucking phone.

Photo: Shutterstock.com

Patrick Cowley, "Kickin' In"

A headline like “Astronomers reveal how Earth will die” offers a brief bit of hope on an otherwise joyless morning, but it turns out that “Earth’s final days” are a long way off so we’re still stuck standing on line in the self-serve lane behind someone who is apparently unfamiliar with scanning technology even though it is 2015 and even old people have managed to master it by now and all the other attendant indignities of daily existence for the foreseeable future. If your plan is to just put up with things until the planet comes to a close you will probably have to scheme up a new strategy, is what I’m saying; otherwise you will be sorely disappointed. (You will be sorely disappointed either way — “sorely disappointed” is about as accurate and concise a review I can offer for life — but also you will be waiting around forever, and what’s more annoying than that?) What to do in the meantime? Fuck if I know. But at least there’s music. I had this one on in the background earlier this morning and at about four-and-a-half minutes in I started smiling quite broadly, almost giggling. There’s just some funny about it, in the best way that word is understood. Barring total planetary annihilation this is likely the only thing that will bring me some happiness today, so I share it here in hopes that it does the same for you. Enjoy.

New York City, October 20, 2015

★★★ Sundry clouds in unrelated shapes were scattered sparsely on the morning sky. The problem of choosing a coat was insuperable; the cold was sure to be going, but it hadn’t lifted yet. The clouds resolved into parallel rows, with blue furrows between them, and for a while the sun was scattered into glare. Then in midday the light came in sharp and straight. The cross streets were darkly shadowed but not as chilly as they looked. By sundown there was unquestionable warmth in the shade. Jackets hung open in the mild and clean twilight.

The Genuine Article

Alexis Lloyd at the Times R&D; lab states clearly something others have been futzing around with for a while:

In May of this year, Facebook announced Facebook Instant Articles, its foray into innovating the Facebook user experience around news reading. A month later, Apple introduced their own take with their Apple News app, which allows “stories to be specially formatted to look and feel like articles taken from publishers’ websites while still living inside Apple’s app”. There has been plenty of discussion about what these moves mean for the future of platforms and their relationship with publishers. But platform discussions aside, let’s examine a fundamental assumption being made here: both Facebook and Apple, who arguably have a huge amount of power to shape what the future of news looks like, have chosen to focus on a future that takes the shape of an article. The form and structure of how news is distributed hasn’t been questioned, even though that form was largely developed in response to the constraints of print (and early web) media.

People tend to shrug off assertions like this — “The Future Of News Is Not An Article” — for being too broad or too obvious or for lacking practical recommendations. (Or for containing the actual phrase “future of news.”) But Lloyd’s post is a set of observations paired with a set of practical, institution-specific proposals. Read it!

Now that Instant Articles are more fully rolled out, and everyone can see them for themselves, I wonder if their formal dimensions will start to seem odd to people. Or… strained? In the run-up, Facebook explained Instant Articles as a way to solve a particular problem: articles, which came from websites, were widely shared and read but loaded slowly. This was a tech issue, simply solved, with some additional obvious consequences: Facebook assuming control over layout; Facebook either influencing or participating with publishers’ advertising and revenue plans in a direct way; Facebook entering into more formal relationships with publications that had previously treated it as an open space in which to experiment. From the user’s view, these articles really do feel like part of their phone’s software — they look and behave like parts of the Facebook app, like pure units of Facebook content. But fixing those issues allows readers to focus on new ones: Why, aside from momentum and expectation, should this native Facebook content look and feel like faster, smoother website content? Why is it still structured like a news article from a newspaper? Why must it have, for example, a headline and a “dek?” Why is the byline where it is? Why does it still open in a new frame?

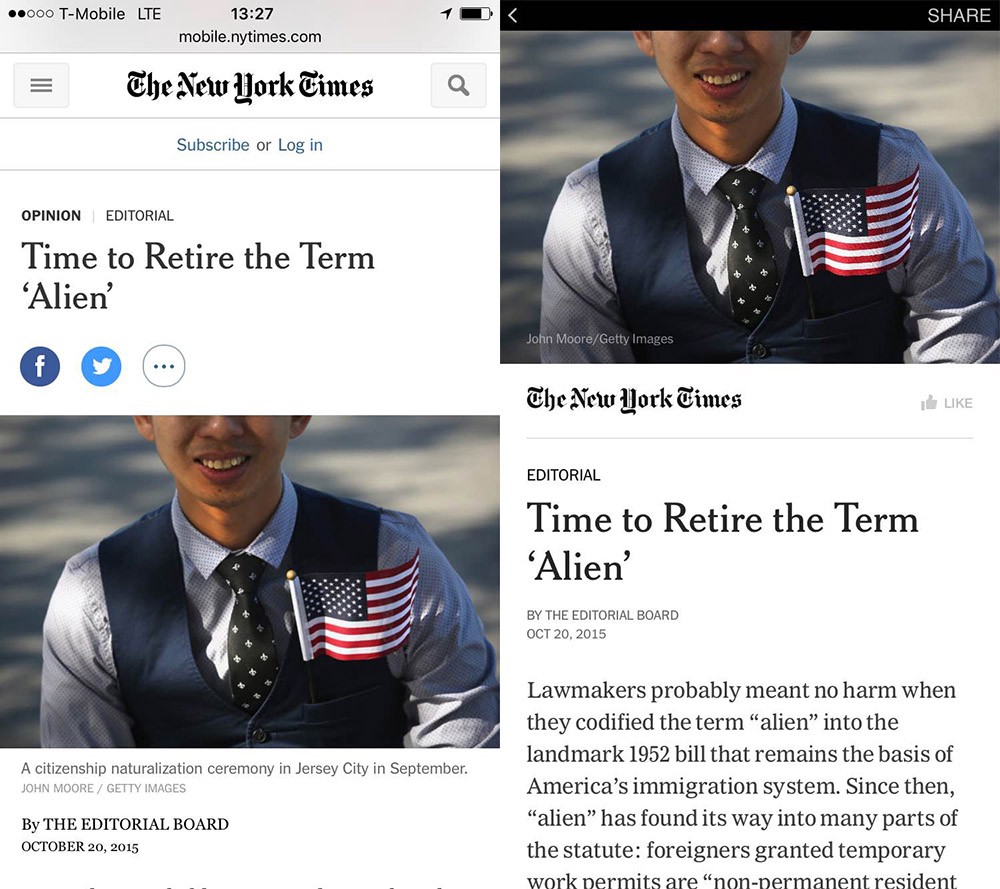

For most readers these questions won’t manifest explicitly, but rather as small contrasts suddenly made more obvious: When you tap an article, you are taken to a page that is, unlike virtually any other screen on Facebook, mostly stripped of buttons and interactivity and interface. It exists outside the narrative and context of the feed but lacks any context or cues to explain or excuse its own suddenly stark quirks. A straightforward inverted-pyramid news article, written in a conventional tone and adhering to a familiar newspaper or magazine structure, feels, as an Instant Article, a bit like a news clipping pasted to a wall. It is technologically native but formally foreign; recognizable and easy to process but clearly removed from its original context. Here’s a single piece in four very different contexts: a paper page, a browser, a mobile device, Facebook.

Print and web:

Phone web and Instant:

This question — what should an article look like in the context of a cascading feed of stuff? — has been lurking below the surface for a while, and lots of people have been thinking about it. That a link would take someone out of their feeds, and into a big messy website, where website conventions — still largely derived from print conventions — meant that these questions weren’t so urgent. But absent that wait, the page-load, the navigation bar, the benefit of years of internalized expectations about where and why particular forms of writing exist, and the subtly transporting experience of watching an external publication gradually piece itself together in a slow pop-up browser, a straightforward news article seems as formally contrived as it actually is.

If Facebook has been focused on solving a narrow tech problem, and advancing its own advertising interests in the process, publishers have been focused, throughout the Instant Articles development and rollout, on maintaining some semblance of control and familiarity. (Or, in a more anxious formulation, on preventing Facebook from absorbing most of their more obvious utility and value.) Both sides were incentivized, then, to create what they did: A faster version of the things publishers were creating in the context of their sites, magazines and papers — things that people were sharing and reading and spending a great deal of time with. But it’s possible this has resulted in the codification, in Facebook’s platform, of a fairly conservative idea of what a news or entertainment organization’s output should look like. It’s in the name! In this view, the advantages gained by partners publishing to Instant are more limited in scope: Your native article, which loads in a faster external frame, will look and perform and likely share better than the linked article that loads in a slower external frame. It has an explicit advantage over links; it is still, as something that takes you out of the flow — unlike, say, a video — at an article-like disadvantage to everything else in the feed. (Among the formal changes made for video in the feed: auto-play, no sound.)

So, a thought experiment! Now, tapping an Instant Article sends you to a separate full-screen page. This is what everyone asked for; this is what we got. But imagine an “article” that just expands in the feed, vertically. What would that look like? What is the feed analog to a post or an article? If it had a headline, would it remotely resemble the types we put on current article pages? The curiosity gap wouldn’t make sense here, for example. But what would? Would the article just start? Would it assume the native Facebook language of the Personal Update? Or would it demand a more thorough kind of preview — a pre-article that could be scanned and either expanded or not? If conventional articles followed from the demands of a newspaper’s layout, then what does a feed-native article look like? Which ones would disappear seamlessly into the feed, perhaps shorter or written in a different style or tone, as their context demands? And which ones would still feel most at home loading separately, in contexts of their own making? The more aggressive approaches to Instant have focused on longer stories, or stories constructed as, like, deluxe interactive slideshows — things that are either meant to stand without much context or that play explicitly with the context and tech of Instant. These are most like the things Facebook envisions in its launch video: big interactive video/text/map/gallery installations; things that explicitly couldn’t exist in the feed. But what about the articles that mostly could? Twitter: SAME QUESTION. There’s also the matter of distribution: Instant Articles are a concept that follows from previous publisher habits — a more thorough extension of the idea might end with some sort of non-feed curation, or a publication-like organizational structure within Facebook, outside the flow, which is kind of what they’re already doing with videos. But why would Facebook reverse engineer the websites it’s replacing? Why not let post types follow from the feed, rather than the other way around? (Lloyd, in her post, goes a step further, trying to find something like the essence of an article, by breaking it down into components. In that sense hers is a bigger project.)

Anyway. No rest for the weary! And maybe the best answer, because who says News Feed has to favor everything equally, is mostly just video.