A Poem by Jennifer Givhan

by Mark Bibbins, Editor

Mars One Candidate Alison Rigby

Pioneers are always ridiculed, but I am doing this for something better, which will hopefully benefit more people than just staying at home and keeping my mum happy.

We start the training cutting out cigarettes & beer.

They show us the kinds of insects we might eat

if we’re lucky. We could die in 68 days after

landing, if we start growing our own vegetables

right away. Something about the oxygen levels

something about nitrogen. We aren’t scientists —

this is reality. My mum wants to know how

they’ll bury our bodies when we go. She doesn’t

believe in cremation. How will the Lord

raise you from the dead when he returns

for the reckoning? She doesn’t wonder if he’ll

make an extra trip to the red planet. He’s

omnipotent — he’s his own time machine. It’s not

like a deep-sea trip or the tundra & soon I’ll be

back on terra firma. It’s death row. But I want

my life to matter. I want to mean it when I go.

Jennifer Givhan is a current NEA fellow and author of Landscape with Headless Mama, winner of The Pleiades Editors’ Prize (forthcoming 2016). Her honors include a PEN/Rosenthal Emerging Voices Fellowship, The Frost Place Latin@ Scholarship, The Pinch Poetry Prize, and inclusion in Best New Poets 2013.

You will find more poems here. You may contact the editor at poems@theawl.com.

Tomorrow's Internet Turns 20

“The newest key person at publishers,” says trade publication Digiday, is the “platform wrangler.” That is: “a strong voice representing their interests at a time when platforms are increasingly the way that audiences find their content and setting the rules for publishers to distribute and monetize their articles and videos.” If a large portion, or a majority, of a publication’s audience is going to be arriving through or on another company’s app or platform, someone probably ought to be paying close attention to those relationships.

This makes sense! The nature of these relationships is currently, to my knowledge, varied but tilted toward tense: platforms such as Facebook and Snapchat aren’t so much courting partners as they are selecting which ones to allow access; platforms want to make the process as easy as possible, and to get advice from their partners, but ultimately have the ability to place their needs first. Publishers fortunate enough to receive them respond to emails from Facebook all like, how high, sir, and thank you. This is a simple matter of size.

So there is a hint of self-flattery in referring to this role as a “wrangler” or a “director” or a “manager,” but I suppose that’s what job titles are for, online, in 2015, where everyone is an editor of writing, or a director of editors, or a leader of projects, of a manager of leaders. Anyway: It’s true. These are jobs that necessarily exist now, that didn’t exist a year or two ago. And they’re surely disorienting ones. This is new territory! Mostly.

Here is some worthwhile reading for our new wrangler/director/managers, and all the people whose jobs depend on their charm and savvy, from almost exactly 20 years ago, published in the Times Magazine.

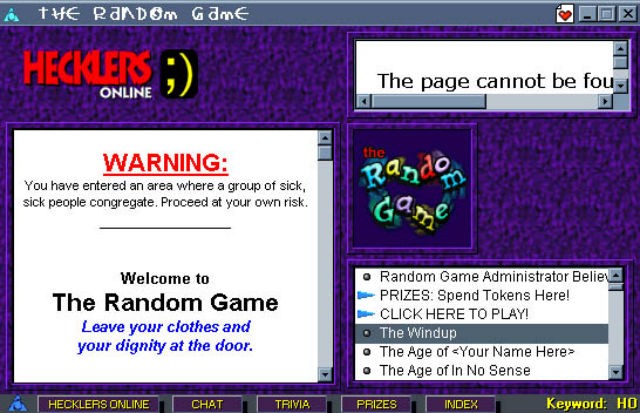

“Cool” is the highest accolade in the [Ted] Leonsis lexicon, and he has conferred it on more than two dozen presentations this year. As a result, the Greenhouse — a unit of America Online that the 38-year-old Leonsis formed in summer 1994 to attract fresh ideas from nontraditional sources — has introduced an array of disparate talents. There’s a writer who bills himself as a 60-second novelist, a site for people of color, a Health Zone, an astrology service, a cyber free-for-all called Hecklers Online and, with midsummer fanfare, Surf Net. Leonsis, who is president of America Online Services Corporation and its chief programmer, promises much more. “Between January and June of 1996, we’ll launch 70 Greenhouse sites, which is equal to all the deals we signed last year,” he says. “I can’t think of a movie studio that productive.”

It’s a feature in the Times Magazine about America Online’s new content initiative, the Greenhouse. At the time, America Online was one of many internet access portals; it had about four million paying subscribers and was growing quickly. This made it the largest provider in a country that was substantially not yet online. But it had a lot of competition, in the form of other providers that were also supplying subscribers with things to read, watch or play with.

Despite its current dominance, the company is vulnerable, and not just to its direct competitors, an increasingly aggressive Compuserve, a revived Prodigy, the yet-to-be-announced News Corporation-MCI Online Ventures service and the enormously endowed Microsoft Network.

The article briefly acknowledges a sort of high-level case against the potential for AOL-exclusive content, walled off to everyone but AOL subscribers, by quoting one of these competitors:

According to conventional wisdom, the only significant destination in cyber-space is the World Wide Web; by this argument, all commercial services are doomed to be nothing more than Internet-access providers. “We see a lot of talent entering the field on the Web without the blessing of the branded services,” says Edward Bennett, president of Prodigy. “And where human attention goes, advertisers will follow.”

But counters with Leonsis’s narrative:

Some commercial services have already positioned themselves as Internet navigators. Leonsis calls them “Johnny-come-lattes” and scoffs at the conventional wisdom. “They all say, ‘Content is king,’ “ he says. “But how can you argue that when there are 200,000 Web sites? The more that’s out there, the better it will be for a service with strong programming.” In other words, with such a huge and bewildering proliferation of sites, users will want a central starting place.

His advantage, according to the piece, is that “he is the first on-line executive who can make a sizable investment in talent.” And the impetus for the project, which went on very visibly for a number of years, was the failure of a previous model.

On most networks — including America Online in pre-Greenhouse days — the economics of cyber-space are attractive to only the on-line service. Typically, these services charge customers a monthly fee that covers the first 10 hours of use. Their profit lies in signing up a great many customers, and then enticing them to stay on line for more than the basic 10 hours. For the independent creators of programming, however, the reward is minuscule: 20 percent of the revenue they generate. In the first wave of on-line growth, services tended to form alliances with established media companies (@times, the on-line version of The New York Times, for instance, has been on America Online since June 1994) and to encourage user-generated content — “chat rooms” and bulletin boards. As services began to look alike, however, it seemed that the key to growth was original programming.

This was unfolding at a point of debate: should media made for internet services be fundamentally different than what came before? And if, as seems to obviously be the case, the answer is yes, how, and with what funding? The partnerships described in the article describe an inverted platform/media relationship in with the latter held a great deal of power. NBC had partnered with Microsoft; Time supplied news for Compuserve. Both had previously worked with AOL; the following year, Newsweek would join the Times with AOL content of its own, after a stint with Prodigy, before launching a website in 1998.

This was a small and confusing world in which a medium’s obvious long-term potential overwhelmed its immediate practical limitations. Internet users are measured in the billions, now; then, a large majority of Americans didn’t have an internet connection. AOL never cracked 30 million paying subscribers; Facebook has a billion a day. Pew puts smartphone ownership at 64% among American adults. Today, each of the major platforms is significantly larger than most, and in some cases all, of its content partners, established or new.

But it’s probably still history worth knowing, if only to force yourself to ask specifically how things are different. Especially as Twitter both courts partners and creates its own editorial product, as Snapchat shuffles partners in and out of its Discover screen based on metrics only it can provide, as YouTube slices its service into paid and ad-supported tiers without much warning to its thousands of partners, and as Facebook negotiates approaches to publishers new and old, while simultaneously suggesting that the future of its core product is largely… video. A different type of platform collided with different types of media companies two decades ago. Some plans worked out for a while, some didn’t. Some of what did was washed away later in an industry collapse.

One of the stars of the initial piece, and of AOL’s in-house editorial operation, was Hecklers Online:

It is Hecklers Online, though, that best expresses Leonsis’ view that the ideal content provider is a party host, not a monologuist. Hecklers is a site where guests are regularly roasted and audience members are invited to ask impertinent questions. “Sean Michael and Scott Davis and I are old friends from high school who spent a lot of detention time together,” says Mike Ragsdale, one of the site’s three founders. “One night we were sitting around drinking beer and we decided to have some fun on line, so we went into a chat room and asked, ‘What is a jihad?’ Someone answered, ‘A holy war.’ We typed back, ‘Isn’t that an oxymoron?’ Then a bunch of us would jump into a chat room and harass the people there until we’d be the only ones in ‘Gay Cops in Houston.’”

An executive or thought-leader type could easily get away with that “party host” line today. And, god, how prescient were these guys in their horribleness? The internet: a place to invade safe-seeming places before eventually turning them into jokes!

I faintly remember some version of Hecklers, after it became a broader internet comedy operation. An article published three years later, and a few years before Hecklers and its spinoffs went quiet, explains where things went wrong:

In December, Hecklers Online, a publisher of humor and games, sent a holiday greeting card promoting the redesign of its site on America Online. The card’s punch line: ‘’All you have to do is find it.’’

This jab at the on-line service that gave Hecklers its start in the summer of 1995 was one of the milder manifestations of a growing frustration among America Online’s small content partners. They were favored children in the company’s early days, when keeping subscribers on line was the way to make money. But in the year-old era of flat pricing, advertising revenues are far more crucial to earnings than revenue from customers who linger on line.

A strategy change, and interface tweak.

In a redesign of the service last fall, America Online buried its partners’ brands under subheadings known as channels…

…

In addition, in the last year, Greenhouse, the division formed in 1994 to incubate services like Hecklers, or Motley Fool, the popular, irreverent site for investors, has shifted gears. Instead of creating partnership deals with start-ups and joint ventures with large media companies, America Online Studios is creating new offerings in house.

AOL had stopped charging for different levels of access and moved to a flat fee. This meant more time spent online was a cost rather than a metered gain that could easily be split between publisher and platform. Now that time had to be be monetized less directly. This would happen through commerce or through advertising. But, the article goes on: “advertising for its partners’ products proved harder to sell than advertising for its own material. As the service began to compete with its partners for ad sales, it began, not surprisingly, to give more prominence to the material it developed.”

Again, this was twenty years ago, so our new Platform Wrangler Evangelist Directors should take it with an old bag of salt. But… lol? “Now, partners are caught in a quandary: Even as the likelihood of their snaring a slice of America Online’s traffic deteriorates, they need the on-line service for its electronic publishing tools, and its audience.” And now we’re talking about time as the most important metric, again? If the people in this article could time-travel forward, look around, and go back home, I’m not sure they’d know what to do differently. Time their exits better? (I guess the real answer is “apply this invaluable future knowledge to literally anything else.”)

Back in 1995, Leonsis, who is now worth about a billion dollars and owns the Washington Capitals and a majority stake in the Wizards, sent off his profile with an oddly dire-sounding quote:

“The Microsoft launch was true to form,” he says. “The expectation their public relations machine creates is very hard to meet — this was a software upgrade, after all, not an AIDS vaccine. But it’s an awesome company, and they will figure it out. The challenge for America Online is to get as big as we can as fast as we can. That means more families, more minorities, more women coming to America Online. And it means getting ready for the backlash against the Internet, when the venture capitalists get burned and customers get lost and the magazines start running articles titled ‘Whither the Web?’ “

Not bad, for 1995. Today, Leonsis can credibly write the following paragraph in a piece for the Huffington Post in 2015:

We believed [twenty years ago] that some day people would consume media — the content they were receiving from newspapers, television programs, movies, and more — online. And we believed in community — specifically in the phrase “vox populi,” meaning “voice of the people,” and knew the Internet would be the platform that could bring the voice to the people.

Leonsis does, however, seem to feel a little burned. Here he states the the lessons he learned from AOL in an attempt at prognostication:

In the next ten years, we will see the definition of media continuing to take on a new meaning almost every day. In a way, the term “media” itself may be endangered as a concept: who is and isn’t a member of the media is harder to understand today than it was when television broadcasters and newspaper publishers were the rulers of the realm. Today, almost every person is their own “media” entity: publishing content on social media, posting videos on YouTube, streaming events via Meerkat and Periscope. Personalities, creativity and content — not distribution — are in control. We can watch what we want to watch, where we want to watch it, and how we want to watch it. Businesses built on restricting or limiting that are bound to fail.

Here, I guess, is where the comparison is both relevant and strained. Who is he accusing of “restricting or limiting?” Is it not the same companies that provide the entire context for the empowerment of the individual he describes? Maybe that’s the Big Intoxicating Idea that’s interfering with everyone’s ability to think clearly, in 2015.

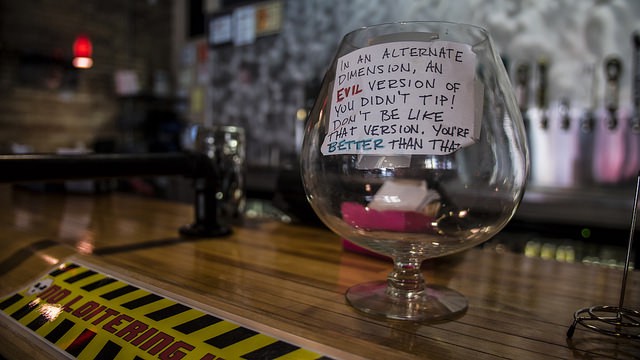

The Tipping Point

Amongst the ranks of elite restaurateurs and critics, a consensus has been forming over the last couple of years that the Death of Tipping is upon us, at least in theory. In recent weeks, Danny Meyer has announced that tipping will be abolished at all of his restaurants, while Tom Colicchio has ended tipping at Craft during lunch hours (for now); many restaurants at the pinnacle of fine dining, like Alinea and Per Se, eliminated tipping years ago.

But as one contemplates the Death of Tipping, one of the questions is whether the American dining public writ large — i.e., people who do not dine out primarily in trend-setting restaurants in major American cities — will accept it as it trickles downstream, given that, in exchange for paying cooks and servers a living wage, it strips diners’ God-given right to dispense economic rewards and punishment as they see fit. For many — most? — the act of tipping, and the threat of not tipping, is less about rational economics than it is about the exercise of power by people who have often relatively little of it over people who generally have even less.

Numerous studies have found that restaurant customers tip more for better service, even when controlling for potential confounds and reverse causal effects… Nevertheless, the relationship between service quality and tip size is rather weak (a correlation coefficient of only .2) suggesting that consumers desire to reward service quality does not appear to be as strong a motive for tipping as self-reported by consumers themselves.

Of course, anyone who has been a server doesn’t need to read a study to know that the quality of service often has little to do what’s left on the table at the end of the meal; a tip is more often than not an insurance policy that a server will willfully accept certain levels of abuse.

But there are now other, less crude, more efficient ways ways to influence the livelihoods of service workers, like the increasingly pervasive ratings system. Diners already love threatening entire restaurants with a poor rating on Yelp or Foursquare, so just imagine the thrill of not merely withholding a small sum of money from a server because he didn’t refill your glass of Diet Coke promptly every time it dipped below the one-third mark, but directly determining whether or not that server is even employed! That is accountability. Consider the lengths that Uber drivers go to maintain their ratings — and their jobs, as recounted by Josh Dzieza:

Many drivers advised smiling and nodding, deflecting potentially controversial topics, and generally avoiding engaging riders any more than absolutely necessary. Several drivers placate riders with bottled water and candy. Another offers them charging USBs and Tide pens. Some offer control of the music, a practice encouraged by Uber’s partnership with Spotify. Several drivers said the best way to behave is like a servant. “The servant anticipates needs, does them effortlessly, speaks when spoken to, and you don’t even notice they’re there,” said a driver in Sacramento.

That driver would be a fantastic server, definitely a solid 4.9 rating.

The technical implementation of an industry-wide ratings system would be more trivial than it seems: There’s a small gold rush right now in trying to take over restaurants’ computer systems, with startups promising to bundle everything from reservations to takeout orders to diner profiles and check payments into a single, seamless system. It’s unclear which systems will win, but conversations with chefs and managers about the dismal state of the restaurant industry’s technological infrastructure have made it clear that the benefits of upgrading to these systems are so extraordinary that it’s only a matter of time before every restaurant is on one. Many will let diners do everything from an app on their phone, and considering how much people love to rate things, especially restaurants — it’s the entire basis of Yelp — what’s one more screen for them to rate their server or cook or barista or bartender?

Meanwhile, as the cost of living in some cities continues to rise and the state-by-state march toward higher minimum wage proceeds — in New York, Governor Cuomo is pushing for a fifteen-dollar-an-hour minimum wage for fast-food workers — restaurant owners have little choice but to to experiment with how to most effectively compensate their staff while staying in business. It’s clear that diners are going to have to pay more, one way or another, but a feeling of greater control — of more power — is maybe one to make them a little more okay with it.

Photo by Aberro Creative

The Dream Of Being Better

When you can’t sleep at night and you lay very still thinking about the stupid things you’ve done and said you sometimes let yourself fantasize about what it would be like if you could go back into the past and put yourself in a different position. “If I had only made a better choice at this moment — or even no choice at all — everything would be okay now,” is what you let yourself believe as your brain unspools an alternate reality in which all your actions were good ones. But then the same little voice that is keeping you awake in the first place pipes up and says, “Yes, but remember the bad thing you did before that?” And so you’ve got another event that you mentally undo, and the satisfaction that comes with imagining how things would all be okay if you did that one right lasts for a little bit until an even earlier misstep emerges from your memory. Eventually the dawn breaks, you haven’t slept in hours, and you understand the only way to have kept yourself from all the heartless, hurtful acts you’ve spent your selfish life committing would be to have never been born in the first place. Then you realize that never having been born in the first place is the only dream you have. But it’s impossible. You can’t turn back the clock that far. You can’t even turn it back a little. Except for this weekend, when you turn it back an hour. Try not to fuck that up that way you’ve fucked up everything else, okay?

Photo: Shutterstock.com

Do You Yak to Your Siblings About Sex?

by Logan Sachon

This post is brought to you by Hulu’s Original series Casual. Join the conversation; check out the latest episode of Casual on Hulu.com! New Episodes Wednesdays.

In celebration of and homage to the new Hulu show Casual, wherein a divorced mom, her teen daughter, and her bachelor brother all find themselves living and dating under the same roof, we asked several people with siblings whether they talk to those siblings about sex and dating. Here are their (horrified) replies:

“My brother and I have never acknowledged the existence of sex to one another in any way, shape, or form, and we probably never will. We do sometimes talk about dating, but that’s pretty unavoidable, since he’s been with his girlfriend for seven years now. Even still, I hear much more about what’s going on between them from my parents than I ever do directly from him. We’re practicing Jews, but this extreme emotional closeting is how you know that on my mom’s side of the family we are descended from WASPs.” — Gillian, 28

“My sister tells me everything, I wish she’d tell me less. I begrudgingly answer all of her questions, but she really has to work for it to get any information out of me. I don’t think our brother has ever given anything up.” — Tina, 32

“I don’t talk with my older brother about it very much. He lives in Europe so it’s not really an option. We email once in a while about someone we are dating once in a while though, and he was the probably the coolest and most supportive person in my family when I mentioned I was dating women, not only men.” — Chloe, 29

“I tell my sister everything to the point that it’s gross, and I literally don’t talk to my brother ever about anything. But not because of gender norms — they’re just like that I guess.” — Aimee, 36

“Sex? Good god never no. We are virginal siblings, pure as morning’s first dew.” — May, 30

“The first I heard of my brother’s girlfriend was when she became his fiancé, if that answers your question. We are not close. My dad, on the other hand, wants to know everything. — Neil, 26

“It’s different with each of them. My younger brother was the first person I told when I lost my virginity, and we’ve had a few conversations about sex and relationships, normally around the time one of us was going through a breakup. It’s not a normal topic of conversation for us, but I do feel that I can talk to him about anything if I need to. My older brother and I do not talk about any of it at all, besides me asking about his girlfriends. He doesn’t want to hear about it!” — Diana, 31

“I have younger sisters, and I tell them nothing, and they tell me nothing. That’s not true. I ask if they are being treated right, and they say yes. Though to be honest, this seems more of a ritual than any actual information being exchanged.” — Tom, 33

“We definitely don’t talk about it. I think it maybe gets inferred, that we’re dating someone, when we text what we’re doing, oh I’m watching a movie with so-and-so, so many of those and we pick up on it. But nothing explicit, no. No announcements or proclamations or probing questions. We’re quite proper.” — Fiona, 29

“Uh, no, my brother and I do not talk about sex and dating. God. No. He doesn’t want to know! I don’t want to know! I think it’s best to just … not think of your siblings as sexual beings at all. Like pets.” — Gemma, 29

Some Bad News About The Asteroid That Will Kill Us All

Those of us who spend our days longing for a giant piece of space rock to wipe all human life from the face of the planet will find only disappointment in this list of the objects currently hurtling toward Earth. I understand your chagrin, and I’m frustrated too. But as an optimist I will remind you that Science is often wrong, that the unexpected occurs with some regularity, and that there are plenty of other things we as a species are doing right here, right now, that may result in our extinction without even needing to be eradicated by a massive impact from the skies. Cheer up, it could still happen. We will all die yet!

Francis, "Follow Me Home"

I cannot quite define what this song makes me feel but that fact that it makes me feel anything at all seems like a reason to recommend it. Wistful, maybe? It’s something, whatever it is. Anyway, enjoy. [Via]

New York City, October 27, 2015

★★ The early high clouds didn’t look like much but they were moving swiftly and they were able to scatter the sun. By downtown they had become puffier and had begun to form a loose matrix. The sun came through valiantly in a spot or two, lighting up a boom crane in the distance, but the light kept getting duller and the clouds more featureless, till a decisive chill and gloom settled in, and the mere feat of standing out on the sidewalk became a chore.

32 Great Recorded Performances of Johann Sebastian Bach's Goldberg Variations

32. Kurt Rodarmer (Rodarmer guitar transcription)

31. Konstantin Lifschitz

30. Maria Yudina

29. Trevor Pinnock

28. Rosalyn Tureck (1994)

27. Maria Tipo

26. Canadian Brass (Frankenpohl brass arrangement)

25. Wilhelm Kempff

24. Kenneth Gilbert

23. Gustav Leonhardt (1983)

22. Simone Dinnerstein

21. Dong Hyek Lim

20. Chen Pi-hsien

19. Wanda Landowska (1933)

18. Andre Vieru

17. Marcus Becker

16. Angela Hewitt

15. Igor Levit

14. NES Chamber Orchestra (Sitkovetsky transcription)

13. Jeremy Denk

12. Céline Frisch

11. Glenn Gould (1959, Salzburg)

10. Tatiana Nikolayeva

9. Nodar Gabunia

8. John Kamitsuka

7. Murray Perahia

6. Ton Koopman

5. Charles Rosen

4. András Schiff (2001)

3. Zhu Xiao-Mei

2. Glenn Gould (1955)

1. Glenn Gould (1982)

Television Kills

“[C]ompared to those who watched less than one hour per day, individuals who reported watching three to four hours of television watching per day were 15 percent more likely to die from any cause; those who watched seven or more hours were 47 percent more likely to die over the study period. Researchers found that risk began to accrue at three to four hours per day for most causes they examined. The investigators took a number of other factors into consideration that might explain the associations observed, such as caloric and alcohol intake, smoking, and the health status of the population, but when they controlled for these factors in statistical models, the associations remained. Another important finding of the study is that the detrimental effects of TV viewing extended to both active and inactive individuals.”