Arandel, "Section 6"

This eleven minutes of this track pass by so quickly that you are not even aware that eleven minutes have elapsed. Unfortunately, eleven minutes is about all the daylight we get these days, so once it’s over it’s dark again. Sorry. Enjoy, though!

New York City, November 17, 2015

★★★ So this was what the puffy vest was good for, the chilly wind coming through the lobby door to begin the march to preschool. The gum in the pocket had no elasticity left in it. The fallen leaves were not even brown, faded beyond color. Shocking berries, the color of fresh blood, hung in the branches of a scrawny tree. The flag at half-staff outside the high school knocked against its pole with that dull particular flagpole chime. Out the office window, across the street, the vertical patches of sun moved inexorably west to east along the south-facing building fronts, marking time. The moon in the clear dark sky over Union Square had thickened a little.

Watch Trevor Noah Get Diplomatic With David Holebrooke

by Awl Sponsors

Get More: Comedy Central,Funny Videos,Funny TV Shows

In this clip, Trevor Noah interviews David Holbrooke, director of the documentary The Diplomat. Noah wastes no time employing the language of foreign affairs, calling his own recent appendectomy an “internal incident that happens when one part of your body disagrees with the rest of your body.”

One of the recurring subjects Noah and Holebrooke discussed at length was David’s father, the famous diplomat Richard Holebrook. Throughout the interview Holebrooke senior is called a “ diplomatic rockstar,” and compared to Michael Jordan, Dennis Rodman and…Forrest Gump. But you’ll have to watch the clip to find out why.

Catch the Daily Show weeknight on Comedy Central or on the Comedy Central App.

Quiet Village, "Untitled (Vocal Version)"

I had something happy to tell you but then I was made aware that the sun sets tonight at 4:35 and now there is nothing I know that will leaven your load. The best I’ve got is this music, which seems like it might work as a soundtrack to the darkness that rapidly approaches. That’s not a whole lot of help but it’s better than nothing. Sorry/enjoy.

RIP Details

It had been expected for some time in the run-up to media layoff season that Condé Nast would close its less-loved-but-certainly-not-lesser men’s magazine Details and lifestyle publication Self. Well, here’s the official memo, announcing that Details will cease to exist — get ready for GQ Style Dot Com — while Self’s sales team will be merged with Glamour’s, possibly in a run-up to going digital-only:

Today, our premium digital network reaches an all-time high of 98.6 million consumers — nearly double the size of our audience just two years ago. We also rank #1 in comScore’s Lifestyle Category among affluent millennials, a position we have held for 24 consecutive months. As we evolve our business and respond to the changing behavior of our audiences, we also need to change how we work with our advertising partners.

With this in mind, today I’m pleased to announce that we are bringing together the sales and marketing teams at Glamour and Self. Under the direction of Glamour publisher and chief revenue officer Connie Anne Phillips, the unified teams will leverage the audience scale of two great brands and create a leading women’s advertising platform for our clients. The editorial teams at both brands will continue to operate independently and maintain their unique voices and perspectives.

Additionally, we have decided to build on the success and massive overall audience of GQ as our men’s brand, and will be expanding the business through their GQ Style franchise. GQ Style, which has consistently been popular among upscale millennials and luxury advertisers alike, will significantly expand its digital presence and also increase to a quarterly print schedule.

As a result of these changes, Details will cease publication with the December 2015/January 2016 issue. Details.com will continue to operate as we transition to GQStyle.com in the coming months. Details editor-in-chief Dan Peres and publisher and chief revenue officer Drew Schutte in addition to Self publisher and chief revenue officer Mary Murko will be leaving Condé Nast. I would like to thank Dan, Drew and Mary for their many contributions over the years.

Our audience results speak for themselves and prove to me that we are well positioned for future growth and vitality. I’m looking forward to working with all of you toward making that a reality. Thank you for all of your continued hard work that makes Condé Nast a world-class media company, without peer.

No word on if this month’s “all-time high of 98.6 million consumers” and being “#1 in comScore’s Lifestyle Category among affluent millennials, a position we have held for 24 consecutive months” once again merits free coffee from the Condé Coffee Bar — or when the real Condé Nast purge will take place, courtesy of FTI Consulting.

The Cool Way to Brew Good Coffee

A month or so ago, at the emphatic suggestion of Foursquare, I walked into an unfamiliar coffee shop — one with tall brown bags of freshly roasted beans lined against one wall, each with a precise little sketch of the origin of its contents; a small armada of Mazzer and Mahlkonig coffee grinders; and the day’s menu scratched out in chalk above the barista’s head — and asked what was good. The barista waved off the pourover cone balanced on Hario’s official VSS-1T Acrylic Stand with Drip Tray, the Aeropress, the siphon brewer, and the espresso machine sitting on the bar. What I wanted, the barista said, was the regular coffee, fresh out of the giant automatic drip machine that everyone has seen in a million coffee shops and diners, which was guaranteed to be “unlike any other drip coffee I had ever tried.”

This exchange was a series of dog whistles between two obnoxious people: I wanted the coffee most appealing to a coffee jerk; the barista told me that this shop was aggressively Good. If you are not a beanboi, but are vaguely aware that a certain kind of highly conspicuous consumer likely enjoys “pourover” coffee which is made agonizingly slowly, one cup at a time, then you might be wondering how an automatic machine that brews like a gallon of coffee at once became a Cool Brewing Method in this age of All Things Craft. (Or not! RUN AWAY FROM THIS POST NOW, SAVE YOURSELF.)

A mildly condensed history of Cool Brewing Methods for Good Coffee might go something like this: In the beginning, which is like Seattle in the late eighties and early nineties, espresso machines were the only way to make Pretty Good Coffee, just like the Italians did, and it was Cool for a long time because who doesn’t love a good cappuccino. Then, as the coffee became truly Good in the early years of the new millennium, according to the purveyors of Good Coffee anyway, Good Coffee shops like Stumptown wanted to show off all of the Good Coffees that they personally discovered by launching expeditions to far away places. In order to do that, they wanted customers to be able to pick any coffee that they wanted to drink, any coffee at all, so they could taste the difference between a bean from Guatemala and one from Ethiopia. This meant that baristas needed to be able to brew one cup of Good Coffee at a time. So baristas did, for a little while, using French Presses and various pourover cones, and barely anyone noticed then, because there were not that many Good Coffee shops yet. And then, one day, in the mid-aughts, a startup called the Coffee Equipment Company invented a machine called the Clover that cost $11,000 and made a single cup of Good Coffee to precise specifications in less than a minute, and even better, it made the exact same cup of Good Coffee every single time at the touch of a button. A lot of Good Coffee shops, of which there were now many more, bought one and they were very happy. But a couple of years later, in 2008, Starbucks bought the Coffee Equipment Company because it wanted to be more like a Good Coffee company. This made the Good Coffee shops sad, so they all got rid of their Clovers even though they all still wanted to brew one cup of Good Coffee at a time. That is when many Good Coffee shops rediscovered “manual brewing methods,” like pourovers or siphons or Aeropresses, which became Cool Brewing Methods for Good Coffee. For a while, things were Cool and Good.

But, over time, people in the upper echelons of Good Coffee began to whisper that maybe manually brewed coffee is not all that Cool, at least not all the time: Humans, especially hastily trained ones who didn’t want to serve coffee their whole life, were way less consistent than machines (weird!), so one cup of pourover might taste pretty good, while the next tastes pretty bad; brewing coffee in a Chemex takes a long time and maybe the barista could be doing better things, like interacting with customers instead of staring glass-eyed into a pile of coffee grounds and slowly dripping water onto it like a dying flower bed; most customers — and there were so many customers these days — would be extremely happy to get their coffee in like five seconds instead of five minutes, even if it was slightly less Good; and also something something bed depth, refractometer readings blah blah, extraction yield yadda yadda. (Also, it did not help that a lot of Fake Good Coffee shops had emerged recently to take money from the growing ranks of people who now wanted Good Coffee, serving them bad coffee made with Cool Brewing Methods while saying all of the same things that Good Coffee shops tend to say, like, “meet the farmer, here is his picture, please enjoy consuming his soul with every drop.”)

Meanwhile, a number of coffee people began to wonder: What if we could replace like, at least part of the sloppy human barista with a machine so that we could brew Good Coffee more consistently but have it still look Cool? That would be very Cool. And so some coffee equipment people made hot water fountains that cost a lot of money and would automatically spray water set to very specific temperatures at ground coffee for a set amount of time. There were also ghosts of Clover past that cost thousands and thousand of dollars and made one cup of coffee at a time or maybe even two or four or whatever, and these new automatic machines promised a lot of the same things that the Clover did, like control and repeatability and precision and consistency. (“Consistency” became a word that coffee people liked to use a whole lot around this time. They still love it. They are very consistent about it, you might say.) It turned out that while Good Coffee shops thought there were some good ideas there, like customization and automation, they had no interest in buying another set of $10,000 machines to brew only a cup or two or coffee at a time, so these did not become the next Cool Brewing Method after all, even though the new coffee equipment people tried very hard to make it that way.

While all of that was happening, Good Coffee became more popular than ever, and so many people wanted it that many Good Coffee shops could not keep up with the lines, especially in the morning, no matter how many baristas they had leaning over racks of coffee, constantly pouring and pouring and pouring. This made some Very Good Coffee people think: What if we could brew a whole bunch of coffee at once? So, a little while ago, a number of Very Good Shops began brewing coffee in FETCO Extractors, which are basically exactly like the coffee machines that normal people have at home, except that they are much larger and they brew liters or gallons of coffee at a time, in large batches — hence the industry term “batch brew” — and are already in lots and lots of restaurants and coffee shops. (What made these batch brewers different is that, inspired in part by all of the things that led to those fancy $7000 water fountains, they were slightly upgraded so that it was easier for baristas to be very picky about all of the things they like to be picky about, like water temperatures and dosage and whatever, you’re already asleep.) This was also maybe a little ironic retro pique at first — sort of like fancy bars reviving shitty seventies cocktails to flick their nose a bit at the recent ubiquity of speakeasies and $12 pre-Prohibition-style cocktails — but then it was not at all. Batch brew was, in fact, some Very Good Coffee people argued, maybe the Coolest Brewing Method of all: A “properly tuned” FETCO could brew truly Good Coffee, more precisely and far more consistently than any human with any manual tools, so that if you got it right, every single cup in a batch was Good; it frees up baristas to truly interact with their customers, whatever that means; and it brews rivers of coffee so an overwhelmed barista can fully quench the morning crowd, no matter how large or how thirsty. More than that though, Good Coffee made in a batch brewer was maybe a little subversive, which is part of the point, at least in some of these Very Good shops: It shuns all of the standard and obvious visual signifiers of Good Coffee, like swan-neck kettles and Japanese ceramic cones and ceremonial arm swirling over every cup; in fact, batch brew’s largely invisible mass production makes what’s being served look a whole lot like regular old coffee. But it’s Good Coffee. (What an ideal: What if every cup of coffee was just Good, without making a big deal about it? Too late, right? lol) And so, as Very Good Coffee shops began serving batch brew, it became a Cool Brewing Method.

Anyway, so that’s what this barista was trying to tell me: This shop was using a Cool Brewing Method, implying a certain level of quality, or at least like, striving to, all by using this unremarkable coffee machine. It turned out that the coffee was extremely terrible, but that was beside the point.

Photo by yoppy

New York City, November 16, 2015

★★★ It was mild enough that the ongoing fight over the younger boy’s winter coat could be suspended. Building corners were sharpened. Light and reflected light turned the two boxes of a crosswalk signal into three boxes’ worth of shadow: two faint ones flanking a dark overlapping one in the middle. The temperature was in the office climate control system’s zone of haplessness, leaving the indoor temperature in the sort of chill that convinces the deep brain that outside must be worse. A shallow recess running up the brick wall by the parking lot became a chasm of shadow.

The Uber Counterculture

The Data & Society Research Institute, with a researcher from NYU, conducted an extensive study of Uber’s labor issues though “sustained monitoring of online driver forums and interviewing Uber drivers.” It’s a surprisingly breezy document, given what it is, and bears out the types of things any frequent Uber passenger will eventually hear if she bothers to ask. It’s a survey, in a way, of a sort of on-demand labor version of a workplace culture developing among Uber drivers. And it isn’t an especially happy one.

Our findings coalesced around the dynamics of Uber’s system of surveillance and control over workers’ behavior. Our conclusions are two-fold: first, that the information asymmetries produced by Uber’s system are fundamental to its ability to structure indirect control over its workers; and second, that Uber relies heavily on the evolving rhetoric of the algorithm to justify these information asymmetries to drivers, riders, as well as regulators and outlets of public opinion.

Each section is fascinating. On Uber’s use of the language of entrepreneurship:

Drivers risk “deactivation” (being suspended or removed permanently from the system) for cancelling unprofitable fares. The Uber system requires drivers to maintain a low cancellation rate, such as 5% in San Francisco (as of July 2015), and a high acceptance rate, such as 80%

or 90%. Drivers absorb the risk of unknown fares, even though Uber promotes the idea that they are entrepreneurs who are knowingly investing in such risk. This discourse of entrepreneurship in the tech sector is the legacy of a Silicon Valley environment where highly skilled and mobile workers could take on risks and trade-offs to be part of the start-up world, but this rhetoric of risk has effectively been retooled to suit a contingent of lower-income workers who are recruited to perform service labor, not highly-skilled technical work.

On drivers’ contempt for Uber’s “driver-partner” characterization of their non-employment employment:

Drivers in this study generally treated the language as either a formality, hypocrisy, as irrelevant, or as a lever to press negotiations for more autonomy. However, the terms “partner” or “sharing economy” both work to express engagement and commitment to similar goals — in this instance, to align the driver’s goals and motives with that of the company through the articulation of social bonds — even when they are distinctly out of alignment Uber has full power to control and change the base rates its drivers charge. Uber’s agreement with its “Partners” (drivers) permits drivers to negotiate a lower fare, but not a higher one (Uber Partner Agreement Section 4.1, 2014). Some drivers report strategically ending a trip early, and thus lowering the fare for

the passenger, in the hopes of getting a higher rating. Rates, as well as minimum fares, vary across cities3; while Uber implies that drivers have the “freedom” to charge less, Uber still asserts almost total control over their drivers’ remuneration. At their lowest, these rates are discussed in forums as a net-loss for drivers after factoring in overhead costs. Uber also perennially and unilaterally changes the commission it takes from each ride, ranging generally from 20–30% for uberX drivers.

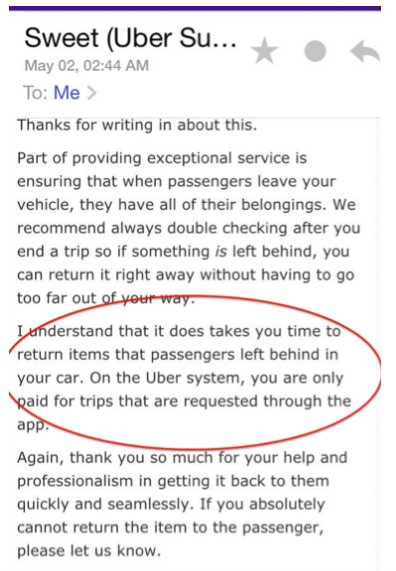

On drivers’ points of contact with the company, Community Support Representatives, who are themselves independent contractors held to driver-like performance standards and subject to driver-like indirect management.

[Their] responses often lack a nuanced understanding of the context or challenges of their work, and drivers have to be persistent to get the answers they seek to questions without a template response. Some perceive that software is creating initial responses based on the keywords in their text, and they refer to CSRs as “Uber’s robots.” The responses drivers receive often resemble generic FAQs, and some drivers write “escalate to manager” in the body of their text in the hopes of flagging a human supervisor more quickly. The role of the CSR more closely resembles customer service than management.

(This bears repeating: Uber doesn’t just outsource driving — it outsources its communication and conflict with those outsourced drivers.)

On Uber’s requests for drivers to help them preempt the same surge-pricing conditions that might allow them to make more money:

For drivers, the most tangible evidence of Uber’s data collection and analysis emerges through predictive scheduling communications that Uber sends to its drivers regarding surge pricing and high demand. Some drivers view this attempt at predictive scheduling as undermining their ability to make more money, and describe how they resist Uber’s attempts to predict and plan for “supply and demand”, such as by refusing to submit information about their intended working hours to Uber when that information is solicited. For example, Uber sent drivers in Atlanta notices that demand would be “off the charts” on Labor Day weekend, and surveyed drivers to “help us [Uber] plan supply and demand.”

On Uber’s ability to act with all the authority of an employer — making specific demands about how all its contractors must conduct their work — while maintaining their status as contractors.

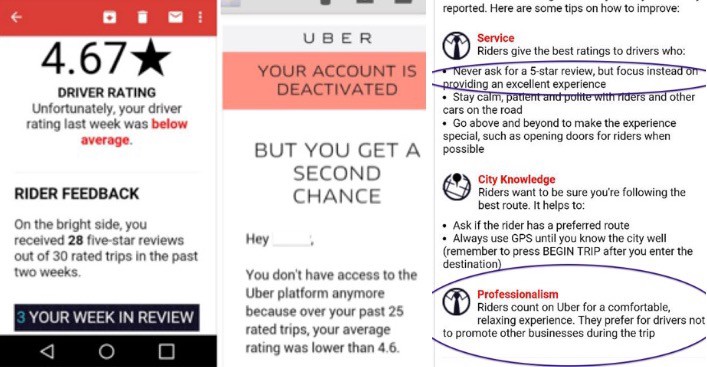

Uber also exerts significant control over driver behaviors through its driver rating system: in it, passengers are empowered to act as middle managers over drivers, whose ratings directly impact their employment eligibility. This redistribution of managerial oversight and power away from formalized middle management and towards consumers is part of a broader trend in flexible labor: companies or platforms can create expectations about their service that workers must fulfill through the mediating power of the rating system.

(By setting specific consumer expectations for driver behavior; by giving customers the ability to rate their rides according to deviations from those expectations; by assigning the blame for those ratings, the true importance of which is concealed from the riders, entirely to the driver.)

Consider this line on Uber’s website regarding lost items: “Visit riders.uber.com/lost to retrieve a phone number to contact your driver and arrange the return of your item.” Then consider, as included in the study, this response given to a driver asking about item returns:

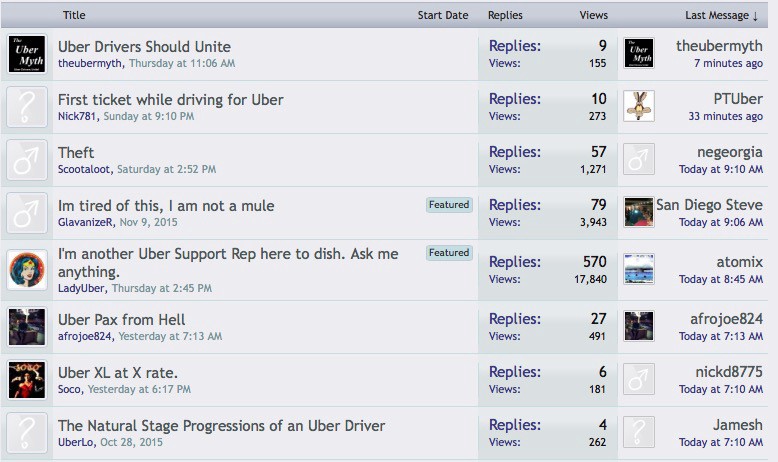

But perhaps the most interesting part of this study, and one that should be interesting even to ideological opponents who might be tempted to dismiss this research outright, is the outline it draws of Uber contractors’ attempts to take back power, either through crude organization or individual data collection. It surveys driver experiences as gathered from interviews but also from the numerous Uber driver forums, which together have thousands of members and display, in general, an oppositional attitude toward the company.

This is labor organization refracted through forum culture: there are calls for collective action next to flamewars; there are trolls and apparent astroturfers; there are political battles in which drivers mockingly tell other drivers “it’s a job, not a career.” There are memes! There is, in the absence of any sort of physical interaction or official means of driver communication, a work culture. Here is a post from a few weeks ago called “The Natural Stage Progressions of an Uber Driver.”

New Driver:

“You mean tell me I can make $1500/wk just by driving people around?! That’s not hard at all. Sign me up! I’m going to be the best Uber driver ever!”

3 Month Driver:

Uhhh….why are my ratings still dropping? Am I doing something wrong? I gave out water, and snacks like Uber told me to. Guess I’ll just have to try harder next time.

6 Month Driver:

“WOW another rate cut?! Man f$%# Uber! How are we supposed to make money with all these new drivers on the road? And they’re raising SRF too? Man….these Pax are really starting to get on my last nerve. Oh look…another water bottle/candy wrapper left on the floor!”

Veteran Driver:

“F$#& this s$#*! My only job is to get the Pax from point A to point B. To hell with Uber and their stupid Pax! And why the hell do they keep calling my damn phone? Learn how to drop a freaking pin people! I’m going to start giving more priority to Lyft from now on.”

Ex Driver:

“Just found a job as a pizza delivery guy. Uber can suck it! I’m out!”

(Sample response: “Correct down to the Dominos job…..”)

The study also mentions ways in which drivers attempt to combat the information asymmetry that defines their relationship with Uber. Hidden cameras!

A fare is “guaranteed” through the credit card a customer has on file, but Uber sometimes retracts it from a driver’s earnings if the company decides that the driver has erred. For example, a passenger may complain about an “inefficient” route. However, there may be physical obstacles invisible to the navigation system; passengers also sometimes instruct drivers to deviate from the GPS-suggested route, or ask for multiple drop-off points for a group of passengers. Some drivers have begun to self-monitor by acquiring dash-cams that face the passenger, so they can use their own surveillant “data” to produce a counter-narrative to the one that Uber presents. Others track their rides manually or through another app in order to verify their pay records. In lieu of other forms of empowerment, dash-cams and alternative logs enable drivers to resist Uber’s power to interpret events unilaterally.

This seems, however, more like last-resort recourse. It’s hard to imagine a situation in which a company that will kick you out of its system for dropping below a 4.6 rating would be supportive, in the long term, of a driver that presented unofficial passenger surveillance footage to contradict a fare claim. But, then again, such a driver might be less inclined to enthusiastically carry out the emotional labor required to maintain such a high rating, or might become bitter over time, in which case the ratings system, with the help of passengers, will sort things out on Uber’s behalf.

Anyway, this is how attempts to regain leverage seem to be starting, with anonymous communication in public and private and with individual attempts at data collection outside of the Uber app. It’s network versus network. It’s app versus app! What will companies like Uber do if these things blossom? A sufficiently massive public forum of disgruntled drivers could become a real problem in Uber’s attempts to find and retain drivers. A larger shadow-network of Uber drivers talking to each other and comparing their experiences could make attempts to manage and contain driver complaints through an email tree less tenable — perhaps more effectively than some Uber drivers’ explicit attempts at labor action. Likewise, Uber might be motivated to discourage drivers from monitoring passengers or making any types of recordings, or from banding together to collect alternate data — about pay, rides, etc — using other apps, because such a thing could be legitimately empowering.

New forms of labor communications are needed to address the inconsistencies of work that is characterized by algorithmic dynamism and ambiguous information flows to improve labor-platform relations. In a bricks- and-mortar workplace, the physical infrastructure is relatively reliable and unchanging. In a semi-digital workplace, small technical changes to the app’s interface, or built-in features that support a dynamic workplace, such as surge pricing and heat maps, can create ambiguity and confusion about worker (and passenger) expectations.

When people in the startup world talk about “algorithmic labor unions,” or a “right to an API,” they might want to look at what people are already doing, and what they’re trying to achieve. (Also worth considering in this context: Airbnb’s effort to mobilize its own users for political gain).

What do they want?

The same data Uber has, at least!

When do they want it?

Before they’re replaced by machines and herded to the next app? Idk actually!!

Accounts Disabled

haha anybody hiring?

— jason (@nonlinearnotes) November 17, 2015

Welp.

— Dennis Mersereau (@wxdam) November 17, 2015

anyone know of any open podcast gigs?

— Taylor Berman (@tcberman) November 17, 2015

I’m confident Gawker will have no problem finding a basic-ass shill to fill my shoes. Dime a dozen. #isityou?

— Jane Marie (@SeeJaneMarie) November 17, 2015

From inside Gawker: “We’re finding out who got laid off by looking at the list of disabled Slack accounts. They’re doing it one by one instead of a group thing. Literally people getting DMed to come into a conf room. And then their Slack is killed.”

Layoffs are currently rolling through Gawker.com and Jezebel (although, at that site, writers were given the courtesy of a phone call from their editor). In addition, we’re told to expect updates regarding Kinja (RIP?) and some shakeups higher in the chain. Longtime manager and recent COO Scott Kidder is apparently leaving by the end of the year; there have also been significant departures — not necessarily layoffs — in ad sales. (Its ad boss left in October.) Other employees who have left the company in recent months (in most cases of their own accord) include Kyle Wagner (Deadspin), Micheal Hession (Gizmodo), Erin Gloria Ryan (Jezebel) and Annalee Newitz (Gizmodo).

UPDATE 3:20: The full count: four full timers at Gawker; one at Jezebel; two at Gizmodo. Each of the following shuttered subsites accounts for one freelancer/permalancer: The Vane (Gawker), Millihelen and Kitchenette (Jezebel), Workshop and AfterHours (Lifehacker), Flight Club (Jalopnik), and Indefinitely Wild and Throb (Gizmodo). So that’s eight more. Valleywag, Morning After and Defamer had no dedicated staff.

Why now? Gawker, despite months of highly public internal turmoil, has had a decent run financially. (Last year was great; this year a little less great. And the forward outlook is broadly, as they say, fjghsldjkfgsldfgsdf. And there’s the ever-looming Hulk Hogan lawsuit, which won’t be resolved for a while.) But it’s also actively courting investment and, perhaps, trying to cut down on costs for potential suitors. The cuts come a day after a former writer, Dayna Evans (edited by former interim editor Leah Beckmann), published a damning account of the company’s treatment of women.

UPDATE: The memo from Gawker Media executive editor John Cook.

All:

As you might expect, since the summer, Lacey and I have given a lot of thought to how to begin to optimize and sharpen all the sites going forward into 2016. Today we are announcing some changes.

We’ve recently corrected a longstanding lack of permanent leadership at Gawker.com that has left the staff wondering what the future holds, and unsure of what is expected of them. While I’m grateful that, under Leah Beckmann’s leadership, Gawker continued to do important and conversation-driving work during its interregnum, I’m also relieved and excited that Alex Pareene is finally in place to start steering it in a new direction.

Pareene’s Gawker will focus intensely on politics, broadly considered, and the 2016 campaign. Never before has a political season promised to be so ripe for the kind of punishing satire and absurdist wit that Alex has perfected over his career — a spirit I saw in action up close when he was a Gawker blogger back in 2009, and also when he was a manager and editorial leader at First Look. The world sadly never got to see Racket, the satirical site Alex was cooking up over there, but Alex’s Gawker will take on some of that project’s character.

Alex will redirect the Gawker team to hump the campaign. Allie Jones and Sam Biddle will head out on the trail, Ashley Feinberg will obsessively monitor the dark and hilarious lunatic fringes on the right and left — will Hamilton Nolan will interview Bernie Sanders? Maybe! Gawker won’t just do horse-race coverage, of course — it will take a Daily Show approach to covering the ever-intensifying culture wars, documenting, satirizing, and reporting on the ways that political disputes are refracted in every aspect of our popular culture. Much of the site’s current editorial palette already fits into this scheme — Andy Cush’s reporting on the Oath Keepers in Ferguson, Keenan Trotter’s revelations about Bill O’Reilly’s domestic violence, and Allie Jones’ swift and sophisticated political jabs. Gawker’s biggest stories have always had a political component, from Toronto’s crack-smoking mayor to Roger Ailes’ paranoia and power to Josh Duggar’s rank hypocrisy. Pareene is doubling down on that tradition.

To that end, we will be redirecting resources to support Alex’s vision. Internally, Tom Scocca, while continuing his role as executive features editor, will return to Gawker in a formal way with a twice-weekly column. Pareene will also launch a weekly column himself. And we will be hiring: Today we are posting job announcements seeking a fast, hungry political reporter with a distinctive point of view and a strong voice, a senior editor to help push the staff to be smarter writers and thinkers, and a deputy editor to help Alex manage his team and run the page. If you have any good candidates, please send them his way.

The shift in focus will necessarily mean that certain kinds of stories that Gawker has trafficked in in the past will go by the wayside, and we can’t reshape the site’s focus without shifting personnel. Unfortunately, Jay Hathaway, Jason Parham, Kelly Conaboy, and Taylor Berman, all of whom have been valuable assets in previous iterations of Gawker, will be leaving.

Gawker isn’t the only site where changes are afoot. As I announced on Monday, Katie Drummond is coming on board at Gizmodo soon and will be announcing new hires soon as she gets to work sharpening its focus and extending its reach. At Jezebel, managing editor Erin Gloria Ryan is hanging up her hat after a total of more than four years helping run the site; we are losing her to Vocativ. Jia Tolentino, whose sharp eye as a writer and editor have enlivened the site, will step up to become Emma’s deputy editor, and Kate Dries will become managing editor; Natasha Vargas-Cooper will be leaving the site as well.

More generally, we have taken a hard look across the whole network at our strategy with subsites. In many ways, we let 1,000 flowers bloom, a strategy that resulted in some successes, like Adequate Man, but also bred confusion among the readers and a thicket of different editorial rabbit holes. To correct that, we made some hard choices: Today we are folding Gawker’s The Vane, Jezebel’s Millihelen and Kitchenette, Lifehacker’s Workshop and AfterHours, Jalopnik’s Flight Club, and Gizmodo’s Indefinitely Wild and Throb. Pursuant to Gawker’s new focus, Defamer, Morning After, and Valleywag will be permanently shuttered, clearing the path for Jezebel to become the primary voice for celebrity and pop culture coverage in the network.

At the same time, we are investing in the subsites that work and trying new things: Deadspin is getting two new staff writer positions for Adequate Man, and Jezebel will be hiring an editor to launch a new health, beauty, and self-care subsite. We’ll continue to evaluate which subsites are working, and which aren’t, and you can expect us to be more discriminating about them in the future.

Finally, I’ve said to a few of you before that one of the consequences of our status as an independent company is that every dollar we spend is a dollar we made. I think it’s fair to say that we’ve all felt some measure of looseness with budgets over the past year as we rapidly expanded and moved into our new space. The fact of that matter is that we need to tighten up, and make sure that we’re strategic and focused in how we deploy our resources. The site leads will have detailed 2016 T&E; and freelance budgets soon, which they will largely be free to spend autonomously — but which won’t be replenished if they spend it too quickly.

I started at this company in 2009 to write stories. I certainly never planned on being in a role where I was responsible for letting go of valued, longtime staff members. It sucks. But as Nick will mention in a memo today, for the first time in my six or so years at Gawker, the company is finally acknowledging what I think most of us in editorial have always known: That we are a media company. We thrive through stories — honest, conversational, hopefully brave stories. We build audiences around them, and communities through them, and generate enough revenue from the credibility we have with those audiences to go out and tell more stories. That has been a radical idea during much of my tenure here, but as of today, we are orienting the company’s mission around it. And if we are to rise to the challenge, we must ensure that all of the sites are laser-focused, loaded for bear, and optimally staffed to do the job. The steps we are taking today are in service of making sure that we live up to the role that we have, at long last, earned as the centerpiece of this company’s strategy for the future.

We will have an all-hands edit meeting tomorrow at 11:30 to talk this through.

Thanks,

John

Almost simultaneously, a report by former Gawker writer Ravi Somaiya in the Times characterized the above change as Gawker being “retooled” as a politics site. Denton has, in the past, expressed admiration — to his employees and, on one occasion, to me — his admiration for explainer site Vox. Writers remaining at Gawker were surprised to find out, today, about their new task: to “hump the campaign.”

In 2008, Gawker Media spun off Wonkette, its politics site, which was at one pointed edited by current Gawker editor Alex Pareene. At the time, Denton’s email staff characterized the decision this way: “As for Wonkette: political advertisers are a strange breed; they don’t come through the same agencies our sales people deal with.”

UPDATE: Elle Reeve at the New Republic notes, regarding Kidder’s departure:

If true, that would mean that following the exits of executive editor Tommy Craggs, advertising head Andrew Gorenstein, and chief strategy officer Erin Pettigrew, only two of the company’s six managing partners named at the end of last year remain with the firm: Denton and president Heather Dietrick.

Perhaps it’s telling that the two people in the photograph for the Times story about this “retooling” are… Denton and Dietrick.

Lastly, Gawker employees recently voted to unionize — represented by the Writers Guild of America, East — but have not yet negotiated a contract. I suspect this will color the conversations!

UPDATE: Aaand Denton’s memo. It’s long.