Lost Soles

by Helen Rosner

This was our first summer in our new apartment, which has a big concrete terrace, and my husband and I bought a grill. A basic Weber kettle, nothing fussy, though I sprang for the fancy charcoal — lump charcoal made from oak, the kind that burns brutally hot and brutally fast. Two chimney starters, so I could get the next round going while the first batch was tearing through its brief and brilliant life, painting a spectacularly taut char on a spatchcocked chicken that had spent two days bathing in hot sauce and onions and buttermilk.

We had friends over on Memorial Day, and I was grilling. I was wearing a t-shirt, I think, and jeans, and I remember very vividly that I was barefoot, because at some point someone was pouring a new batch of viciously hot coals into the grill and a few of them — fiery wisps, glowing red pebbles, a confetti of ash — spilled out over the edge of the kettle and danced around my feet, in response to which which I reflexively danced back, a hot-foot jig to avoid the sudden hail of flames. Of course, both feet, bare and pink, landed right on top of the coals, my entire body weight pressing into the smoldering carbon for two seconds that felt like a thousand years.

I used to worry that I bared my feelings too readily, too voluminously; more recently, when I’m thinking about them at all, I worry that I don’t show them nearly enough. A particularly hyperbolic happiness is no problem, an omg dying! enthusiasm, nor its dark twin, a certain performative despondence that’s half cynical and half exhausted. But real feelings, those used to be easy, and now they’re hard. Which is to say, they’re still easy, but over some set of years and certain therapy-aided revelations, I’ve come to a point where keeping things in is just as easy as — maybe easier than — feeling them in the first place. It wasn’t until I apologized to a friend for spending months being morose and self-absorbed about a work situation and he genuinely had no idea what I was talking about that I had the dawning realization maybe I’d been doing so well at showing less I’d maybe been showing nothing at all.

I wonder if I should be proud, somehow, of what happened when I landed on the coals. I remember feeling a resonant thunder of pain fill my body — it didn’t shoot through me, it didn’t grab hold of me, it was just there, everywhere, like my lungs had hardened and my skin had shrunk and time was stopped and it had always been stopped — and I remember taking that pain and folding it up inside my head in a way that felt, in that moment, strikingly like the process of making an origami mouse, and tucking it away. I remember taking a breath and saying in my normal voice, “Everyone make sure you’re wearing shoes, and someone pour water onto the coals on the ground.”

And then I remember walking, maybe a little faster than normal, but maybe not, back into the house and through the kitchen and the hallway and into the bathroom where I closed the door behind me and sat on the edge of the bathtub and turned on the water and let it wash over my feet, which were charred black in places, and terrifyingly bloodless in others and I sat there and I tried to breathe and I waited for someone to realize that I was gone and I needed help, and to come help me. After three minutes of silence I got up, walking on the side of my right foot (there was a burn the size of a quarter at the peak of my arch) and the heel of my left (the skin on the bottom of my three outer toes was gone, mostly, and what was left was a sickening white), and I cracked open the bathroom door and called out to some girl whose name I never really caught, some lovely, ephemeral girlfriend of a friend, to ask her to ask my husband to come over to the bathroom. After a few minutes he did, and it wasn’t until he closed the door behind him and asked me what was wrong that I unfolded the origami mouse I’d tucked away, and began to sob.

When you’re balanced on the lip of a bathtub, hysterical with pain and terror, your husband frantically searching the internet for what to do when a person steps on actually-not-metaphorically white-hot coals with bare feet, you’re not really in a position to appreciate how morbidly funny it is that most of what comes up on Google is a mix of instructions for how to fire walk as a party trick, and snide news reports of the time the “signature experience” of walking barefoot over hot coals at a Tony Robbins self-help seminar seriously injured two dozen people. A few websites come up that say if you burn the soles of your feet, you should definitely go to the hospital; a few websites say that if you burn the soles of your feet, you don’t really have to. We tried downloading one of those Uber-but-for apps that will send a doctor to your home within an hour, but despite living in a relatively fancy part of Brooklyn, it apparently wasn’t fancy enough to be in range.

It wasn’t until two months later — when my dad, a doctor, took a look at the bottoms of my feet, mostly healed by then but not entirely, and got furiously angry at me — that I learned that my burns had been third-degree. The worst ones, the ones that burn through all your layers of skin, that kill your skin, that can, and I don’t entirely understand how this works, somehow burn your blood. You’re supposed to go to the hospital immediately for a third-degree burn, especially on an extremity — but what were they going to do to me there? The coals were small, my burns were small. They’d have dipped me in antibiotics and wrapped me in gauze, and told me to stay off both feet until everything got better. Which had been, effectively, what I’d done on my own. I spent three weeks effectively immobile, hobble-hopping from the bed to the bathroom to the couch and back again, my husband bringing me bottles of seltzer or a laptop charger or a fresh roll of sterile gauze so I could go through my twice-daily ritual of unwrapping the bandages and staring in fascination and revulsion at my body steadily rebuilding itself, watching blisters billow and collapse as my skin slowly regrew, the bandages changing over the weeks from bloody and wet to clean and dry. Then I’d apply antibiotic burn cream, and wrap my feet away again.

I kept looking for more stories about the Tony Robbins seminar. “It’s a metaphor for facing your fears and accomplishing your goals,” one of the women who’d walked across the coals told the New York Times. Someone else said, “The fire walk is not about the fire walk, it’s about taking steps in life, in anything.” I didn’t really tell my friends I was hurt. No one really seemed to notice. One group thought I was hanging out with another group, and same thing going the other way. I told my boss and a few coworkers that I’d hurt my feet, mostly to explain why I wasn’t in the office for a while, but I played it down. Burning both of your feet on hot coals during a barbecue isn’t a sexy injury, it’s not really very sympathetic. Wear shoes, you idiot.

Later, I reached out to some of the people who’d been at the party when it happened, people who I figured deserved an explanation of why I’d invited them over only to disappear for forty-five minutes, and come back for a while, and then disappear again, to bed this time, curled up with some ancient Vicodin from a long-ago surgery, leaving my husband to refill the drinks and bring out the desserts and eventually say the goodbyes. Most were shocked to hear that it had even happened, even though they — like my husband, who didn’t realize I’d disappeared to the bathroom because I’d been horribly hurt, because I didn’t tell anyone, because no one was looking for it — were standing right next to me when it happened. “Why didn’t you say something?” one of them asked me when I told her, and she meant it with kindness.

I don’t know why. I don’t know why I didn’t really mention it then, or later, or even why I’m bringing it up now, or what it means, or if it matters. I burned my feet this year. It was one of the worst things that’s ever happened to me, to my body. My breathing gets shallow and my throat gets tight even thinking about how scared I was when it happened, how long I stayed scared, how much it hurt, how helpless I felt for a month of immobility, how alone I felt, how Hitchcockian the solitude, how the pain ebbed and flowed and scintillated and eventually subsided, how many origami mice I folded up and tucked away and wouldn’t know how to find and unfold even if I wanted to. I don’t know.

My feet are better now. You can barely tell that anything happened. There’s hardly any scarring, and even if there were more, it’s on the bottoms of my feet. No one looks there on their own, and I’m not likely to show them to anyone, anyway.

Photo by Kenneth Lu

Save Yourself is the Awl’s farewell to 2015.

New York City, December 30, 2015

★ Outside was uninteresting cold and uninteresting gray, while inside the ballet shoes of the snowflakes made a soft tapping sound like sleet as they danced in their lovely blue artificial storm. A child tried out her own dance steps out on the concourse, dark in mid-afternoon despite the vast windows across from it. It was time for a heavier coat again, and the only sudden loudness in the night would be the onset of rain.

New York City, December 29, 2015

★ The rain faded to fog and drizzle. Fat white drops fell from the scaffold outside the door and had to be avoided. Breath misted; parked cars were beaded with about as much water as they could hold. The drizzle held on for a while, then left plain cold gray without even the wetness to distinguish it. The dim afternoon light flushed briefly and unexpectedly yellow, then returned to gray.

How to Make a Difference in 2016

by Vincent Bevins

Dear friends and family,

I write to wish you happy holidays, but also to ask you for your help. As you know, these are dark times for humanity, for our planet, and for our children.That’s why I have decided to return all of my Christmas gifts this year, and will use the proceeds to make cash donations directly to Mark Zuckerberg. Contributing as much as possible to Mark Zuckerberg, founder and CEO of Facebook, will also be my New Years’ Resolution, and I humbly ask you to join me on this exciting journey.

As you no doubt recently heard, Zuckerberg has pledged to donate ninety-nine percent of the value of his company stock to ambitious future projects that he will define over the course of his life. There are two major advantages to this. The first is that he will save humanity. He is clearly the man best able to decide, unilaterally, how this $45 billion (and counting) should be used. The proof is that he made $45 billion. The second is that since his pledge is actually denominated in Facebook stock, everyone can help, even if you are poor. Economy hit you hard this year? Or just short on cash this Christmas? Or maybe you are even from the developing world, where hundreds of millions of Facebook users reside. Don’t worry! As an alternative to direct cash payments to Zuckberberg, you can simply do everything in your power to push up the value of Facebook stock. Spend as much time on the site as possible. Do all your shopping there. Create and upload great content. Just keep doing what you’ve been doing — but more of it — to make him as rich as possible.

Some of my friends have said: Didn’t we sort of do a lot for Zuckerberg already? They say, “Didn’t that guy not even invent anything? Didn’t he just marry three existing technologies — websites, and email, and the sheen of North American university elitism — and then wait for the world’s population to pour their images, writing, and interpersonal communications freely into his servers? Didn’t we actually already make him that $45 billion? And for the last few years, hasn’t he been re-designing the site’s algorithms in an effort to maximize its usage and profitability, consequently fundamentally altering the way our friends and the world are represented to us, with sometimes devastating psychological consequences?”

They’re looking at it wrong. Through the beautiful mechanisms of the market, we’ve successfully carried out an efficient transfer of resources to the man who can best put them to use. It may not have been easy, but no one forced us to sign up Facebook or to keep posting. We poured out our blood, sweat, memes, and identity politics to get him this far.

But think of how much further he could go with our help. Imagine what Zuck could do if he had $50 billion, $60 billion, or even $500 billion. Luckily, we don’t have to imagine, since he laid out very specific ideas in an open letter to his newborn daughter published on Facebook.com.

Can you learn and experience 100 times more than we do today?

Can our generation cure disease so you live much longer and healthier lives?

Can we connect the world so you have access to every idea, person and opportunity?

Can we harness more clean energy so you can invent things we can’t conceive of today while protecting the environment?

Can we cultivate entrepreneurship so you can build any business and solve any challenge to grow peace and prosperity?

How exciting is all of this? But for it all to happen, the world needs to cultivate entrepreneurship. Look around at all that is wrong — so many problems, and not nearly enough businesses to fix them.

Please join me on this quest to help Mark Zuckerberg help the world. I have heard some other idle criticisms from idle people — none of whom have $45 billion — saying things like, “He didn’t even launch a foundation, he just created a limited liability company that can do whatever he wants. Or, if you have $45 billion to spare, it’s not like you can actually use it all to meaningfully buy things, so just launching Pharaonic projects to bend the world to your will sounds like the most fun thing to do anyways. And, if you don’t actually cede control over your resources to to anyone else or some collective decision-making process, it’s not actually charity.”

These points may have some validity. I’m not sure. They are issues which we will, undoubtedly, debate, and resolve over the coming months on Facebook.com. But in the meantime, I will not be caught on the wrong side of history. Will you?

Thank you and Happy New Year. My unborn children thank you, and they thank Mark Zuckerberg.

Photo by Maurizio Pesce

Home for the Holidays

“Home for the Holidays” is a relatively new conceit, emerging only after the rise of the affordable automobile allowed families to sprawl beyond walking distance. Before the invention of the car — and just after the revelry of Christmas was no longer a carnival-esque atmosphere of roving mobs of youthful, white, poor males threatening rich folks into giving them beer — there was no reason to highlight going home. You were already there. It’d be like praising using a tortilla to make a burrito. It’s inherent in the design, so why point it out?

In the fifties, Robert Allen sat at the piano while his songwriting partner Al Stillman stood nearby. They wanted to capture this uniquely American ethos of generational-expansion-then-seasonal-contraction. One of them remembered, or maybe made up, a story about a man living in Tennessee who was heading back home to Pennsylvania. He just wanted some “homemade pumpkin pie,” traffic be damned. In 1954, they published the song “(There’s No Place Like) Home for the Holidays,” and Perry Como lent his dulcet tones to the first recording, released on November 16th, just in time for that Christmas. Ever since, there’s been no shortage of artists willing to foot the cost of the copyright rather than trying to figure out how to more personally capture that murky feeling of nostalgic yearning, of magnetic homeward bound migration, of returning to a save point and weighing if you chose the right path, of familial obligation, of warmth and comfort and comparison. The Carpenters released theirs in 1984; Vince Gill and Olivia Newton-John performed in front of the London Symphony Orchestra in 2000; Cyndi Lauper and Norah Jones combo’d for one in 2011.

On December 1st, 2011, T-Mobile staged a flash-mob “live musical” version of the song in the middle of a Chicagoland mall, in the hopes that it would, as they say, “go viral.” It did, by whatever metric you’re using, but at some point, the phone company decided to remove it from YouTube. One of the unauthorized uploads that remains has a tad over fifty thousand views, with the word “love” showing up eight times in the comments.

I moved to California from the south suburbs of Chicago. It wasn’t a scheduled move with a firm plan or source of income. I was able to lodge with my gracious cousins who’d previously made the westward move — and have since migrated back — and I signed up for a year-long screenwriting class at UCLA. The class was less about wanting to succeed in Hollywood — update: I didn’t — and more about handcuffing me in a single location. I found a not-great job and a just-satisfactory apartment, then funneled my life into earning money during the day so I could write at night. After four years, the night money caught up with the day money, or at least close enough to justify quitting the former. I made $5,000 my first year of writing exclusively.

My nephew turned two this month. My sister and her husband have made the decision to not turn their child into a hashtag, banishing his image entirely from social media. I tricked myself into believing occasional emails with video and photo attachments — along with a bi-weekly FaceTime session — was a reasonable substitute enough for actually being there to watch him metastasize into a male human. There were plans, once, to read a story to him from two thousand miles away via technology, but he’s on a funky schedule, and wouldn’t be able to sit still, and I have a weird work schedule, and I’m also two hours behind, and my internet is kind of shit, and.

Regret is an emotion linked to the past, coming from the examination of decision trees that have webbed out from singular moments littered throughout one’s personal history. The ache that comes is dissonance from lingering on an internalized — and, frankly, unanswerable — debate about whether you should’ve zigged when you zagged. (Unless you’re a fan of the many-worlds theory of quantum mechanics, in which case: Buck up, buddy, you did them all!) Maybe all that money you spent on law school could’ve been put towards anything else, maybe you signing that lease with your partner to “fix things” wasn’t the wisest course, my god will you ever learn to leave Subway’s footlong meatball sub well enough alone.

My mom’s retired, and my dad’s last day at work is approaching. They live deep in the heart of downtown Chicago, across from the eyesore Trump Tower. They used to send me videos of brave window-washers swaying outside their living room, hundreds of feet off the ground. They’re on a first-name basis with all of their security guards. When I come in for the holidays, they call downstairs and my name is scratched onto a “visitor list” that gets tossed into the recycling bin every few weeks. When they’re not at my sister’s house watching their new grandson, they’re taking advantage of the city’s offerings of free and cheap cultural programming. They drink a lot of wine. They recently went to an “avant garde” movie they thought I would have enjoyed.

They’re gonna have a fucking blast these last years together.

Save Yourself is the Awl’s farewell to 2015.

A List of Very Specific Things I'm Sorry About

by Jacqui Shine

Surreptitiously throwing away the stuffed bear my cat liked to drag around the house and hump.

Not drinking the hot chocolate my grandpa made from scratch and brought to a football game we went to just because I didn’t want any hot chocolate.

Anything I Vaguebooked after age 25.

Laughing incredulously when my wife suggested that I buy a Jack Johnson album and sneering, “I don’t evenlike Jack Johnson,” to which she said, in a very small voice, “But you like that one song?” which was true.

Not going to see Dr. John with my mom so I could go see Divine Secrets of the Ya-Ya Sisterhood with my high school friends instead.

Not taking my girlfriend seriously when she said she only wanted to go to Dairy Queen if they used real chocolate soft serve (instead of adding chocolate syrup to vanilla soft serve) and then getting annoyed when she started crying because she got the wrong kind.

Telling the second-grader I tutored that he should wear his glasses the next week so I could see them, and then not recognizing him all afternoon with his glasses on, even though he kept straining his face toward me, hoping I’d notice.

Repeatedly mispronouncing Choire Sicha’s name.

Asking my dad whether the real reason his brother died was because he’d committed suicide, then freezing up when he started crying and said “Yes.”

Taking my girlfriend’s idea for an intro song for her college radio show and using it for mine.

Shaming my brother for supposedly calling a 900-number sex chat line, when it later turned out that my grandparents had been scammed.

Shoplifting crayons from the school store.

Avoiding an ex and her new girlfriend at a wedding like my life depended on it instead of just saying, “Hi”

Not calling my grandma, despite repeated personal vows to phone her weekly — even though part of the reason I hated calling was because she would always say something like “You and your brother are all I have left” or something else otherwise referring to her imminent death.

Telling my counselor that I thought he was the therapeutic equivalent of government cheese, and then doubling down with, “Even if we were in France and the government cheese were brie, I still wouldn’t want it because it’s government cheese.”

Begging my mom to let me wear her special dangly clip-on earrings that she used to, and I quote, “wear to rock concerts” on an ordinary Wednesday and then losing one of them at the grocery store.

Stealing and eating the class weirdo’s Hershey bar during lunch one day in third grade.

Elbowing the girl next to me all night long on the bus to Disney World in seventh grade because I was mad that someone was sitting next to me.

Invoking MLK in an impassioned note I wrote to a girl who was bullying me on that trip who was the only Black student in the entire class.

Attempting to comfort someone complaining that she felt fat by saying, “Well, your sister’s fatter than you are.” (I was at least half feral in seventh grade.)

Putting an open can of Coke in my brother’s hand after waking him up, expecting that he would drink it, not fall back asleep and spill it in his bed.

Fondly referring to a guy in one of my grad seminars as “nebbishy.”

Refusing to eat the peanut butter sandwich my other grandmother made for me one day because she’d cut it in triangles.

Asking my mom, philosophically, whether ugly people “know they’re ugly,” only to have her answer morosely (and unexpectedly), “Yes, we do.”

Save Yourself is the Awl’s farewell to 2015.

Fishy

by Jazmine Hughes

When I became a teenager, I started hating everything, because that’s what teenagers do. Shows I loved were passé, friends I adored dead weight. I hated fiercely. And most of all, I hated fish, for reasons I can’t explain here because those reasons didn’t really exist because I was a teen, remember?

The shaky facts of this hatred aside — I’d literally never eaten fish — my distaste was easy to maintain. My family, which consisted of “tired parents” and “sisters who were pickier than me,” only ate chicken, the occasional bit of beef, and lots of cereal. The closest I ever came to even seeing fish was when they were splayed out at the seafood counter at Stop ’n’ Shop, eyes wide, mouths gaping, proof of recent life hanging like a stench above the ice.

My anti-fish sentiment covered all forms of seafood: Fish sticks were vile; clam strips were repulsive. “Anything that came out of the sea is not for me!” is something I would’ve said if my brain had been trained to think in pithy tweets at the time.

When I went to college, I only ate hamburgers and gained twenty pounds before sophomore year. In between helpings, I gave tours to prospective students. I was energetic and ethnic — the two most salient traits in a college representative — and my speeches were honed to the point where I could enchant any Westchester mom or stockbroker dad or petulant high school senior. (Well, mostly: I told one tour group about the weight I had gained, and a Southern mother looked me up and down, then said, “Looks like you needed it.”) My tours were basically an hour of aerobic stand-up, where I’d work out new material while walking backwards in ripped up Converse. I loved every fucking minute of it: I learned to read a crowd, who I could joke with and who I could give it to straight, who would ask me questions about post-graduation employment rates and who would freak out upon discovering that the bathrooms were co-ed. I had material tailored for every situation, a Rolodex of jokes for every person. And my calves looked really, really great.

The crown jewel of my tour was discussing my first aha moment. Your aha moment, as described by the admission office, was a mental unveiling that every student endured before graduation: The fog of the future was lifted, the answer to a question you didn’t even know you were asking was now as clear as a bottle of Smirnoff. It was important, even as a student, to not seem like a shill; my tours filled to the brim with wry institutional deprecation. But my aha moment was where I got heartfelt and serious: It really the point at which everything clicked, and, while partaking in the rich and various extracurricular activities that one of U.S. News & World Report’s top liberal arts colleges provided to each and every student, I finally decided my career path, which, lol. My moment, naturally, was the first time I saw my byline in the student newspaper.

It predated “Started from the Bottom,” but I was there, then a smiling college senior and the editor-in-chief of the paper, a girl who had followed her aha. I relayed the memory with élan: I roped in school spirit (“The college paper was always a lynchpin to the community, but it was CRITICALLY UNDERSTAFFED”), personal angst (“But was I GOOD ENOUGH TO PUT A PEN TO THE PAGE?”) and professional triumph by way of campus direction (“And my time at the newspaper led to a PAID JOURNALISM INTERNSHIP at a GLOSSY MAGAZINE in NEW YORK CITY, all thanks to our AMAZING career service center, located across the highway, near the rosebushes and just past the fawns!”).

My spiel was superficial, a meaningful breakthrough pumped with cloying significance until it overflowed, but I held on to the idea of an aha moment, even after graduation. The fog in my life had gotten denser, even as I progressed past early-teen angst and opened myself up to liking things again: I just didn’t know what I liked besides writing. (The only thing worse than being a teenager is being a burgeoning adult: the certitude decreases, but the pimples don’t.) But aha moments always come when you least expect them: I wasn’t even looking for the newspaper meeting on the first night I attended one, but a hot guy was talking, so I stayed.

This January, I got brunch with my friend Katie. We went to Mayfield on a Sunday morning, and I remember it clearly. We talked about my boyfriend, who was sick and needed tissues; Harvard; Yale; Abraham Riesman; and “this weird email I’d just gotten from a hiring editor at the New York Times.” We ordered and kept talking — Passover Seder, Brighton Beach, our younger sisters, drug dealers — and our plates arrived. The only thing I don’t remember is what I ordered, but luckily, I remember hers: a toothsome-looking kingdom of bagel and lox. My eyes looked like cartoon characters’ when they fall in love.

I was confused: Why now? Why this fish? My “I don’t like fish” credo rattled in my head — this was my truth, which I’d been repeating to myself for a decade. Since I turning thirteen, I’d changed my hair and clothes and address, added and subtracted from my personality, crumpled and smoothed out my original self over more times than I could count. All I had left were my beliefs, which made me the beautiful, broken person who I am today, and if I altered the core of my inner being then I would destroy the sanctity of the time in my life where I was able to make a choice without totally seeing it thro

“Can I have some of that?” I asked Katie. She obliged.

I took a generous bite with my front incisors. Before I describe it to you, know this: I am not poetic and I am not a liar. The world did not slip away, a chill didn’t come over my body, my life didn’t change forever. But mmomigod: The bite was harmonious and savory, a symphony of flavors. Aha. Maybe fish is… good.

Katie was still talking, so I took a second bite; chunks of bagel and brined salmon flesh stubbornly wedged themselves between my teeth. Mmm, I thought to myself. Seconds.

I don’t know if I believe in God, but I do believe in perfection, in a pre-ordained arrangement of a thick helping of cream cheese (plain, don’t be a monster), generous folds of salmon belly, and hollow, crunchy red onions atop a chewy, pillowy bagel, lightly toasted, all of which are fine on their own but are ultimately made to be consumed together and definitely not with tomatoes. (Capers are a luxury but unnecessary; buying an entire jar of capers is a commitment one should seriously consider before embarking. How often do you buy things that you know will still be in your refrigerator when you are dead?)

I don’t regret a lot from my adolescence, because I really do believe that every single text or locker note or pepperoni bit stuck in my braces coalesced into the mess you see today, a stance that only comes from years of psychotherapy or glancing at Tumblr. But I fucking rue the day that I decided to eschew fish. In 2016, maybe I’ll try cod.

I avoided bagels and lox for 23 years because I “didn’t like fish” but now I want to go back and punch age 1–22 year olds me in the FACE

— Jazmine Hughes (@jazzedloon) February 6, 2015

Photo by Russ and Daughters

Save Yourself is the Awl’s farewell to 2015.

My Best and Worst Purchases of 2015, a Horrible Year

by Leah Finnegan

2015 was a horrible year. Even if you got a promotion or met the love of your life or some shit it was still bad enough for enough people that everyone should suffer in solidarity. Anyway, here is some shit I bought this year that was good, and some other shit that was bad.

Best

Cancer Ward by Alexander Solzhenitsyn (One cannot be free of cancer or Stalin)

A Long Walk to Freedom by Nelson Mandela (Did you know that Nelson Mandela was circumcised at sixteen?)

White pants (When you wear white pants, you are cool and you also feel good)

Migraine medication (I spend about $800 year on migraine medication lol. I love it so much!)

Davines® shampoo (This Italian shampoo costs $25 per bottle lol. I love it so much!)

Some fucked up animal figurines from the laundromat

Law and Order: Special Victims Unit Season 17, Episode 4, “Institutional Fail.” (Whoopi Goldberg guest stars as a social worker with an axe to grind)

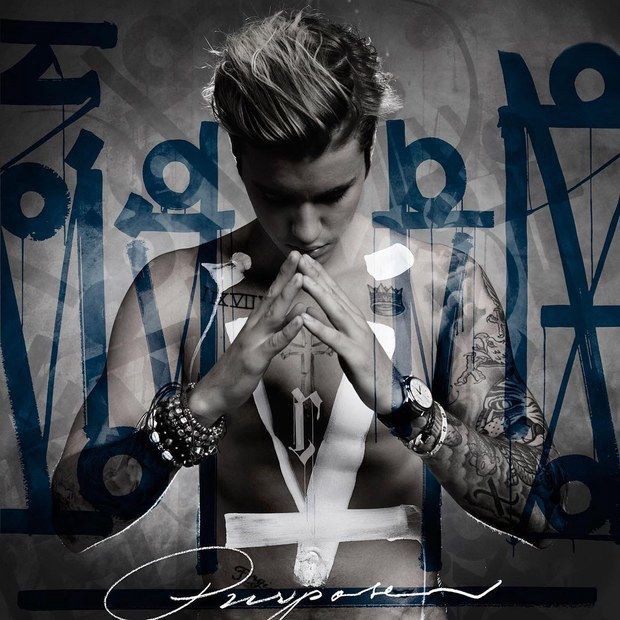

“Purpose” by Justin Bieber (I had never really listened to Justin Bieber before; this album has been very therapeutic)

Worst

“Hello” by Adele (Didn’t really need to own this)

Verilux VT10WW1 HappyLight Liberty Personal Portable Natural Spectrum Energy Lamp (Triggers migraines)

Marijuana Weed Leaf socks (Ordered from Amazon. Never arrived)

Most coffees, tbh (The best coffee is from McDonalds, no sugar with three creams)

Fancy top that I bought for job interviews but only wore to one job interview (It’s a really nice top, by Acne, lmk if you want to try it on)

A Little Life by Hanya Yanigihara (I thought this book was really bad and torture porn? Email me if you agree??)

Stuffed horse that when you turned it inside out it became a rabbit (I saw this on Amazon and I thought it would be really small and I also thought it was just a horse. But then it arrived and it was pretty big and also became a rabbit when you turned it inside out. Fucked up and a waste of $7.99)

Bathing suit from dollar store (Don’t buy a bathing suit from the dollar store. It will fall off in the ocean)

Save Yourself is the Awl’s farewell to 2015.

Milling Time

by Max Read

If you’re like me, you spend too much time saying, “if I had the time.” It’s a nice self-deception cantrip, a handy little shoehorn for forcing your hammer-toed ambitions into the stiff life you’ve arranged for yourself. I quit my job earlier this year and suddenly, for the first time, I had… time. I was going to write a novel. I was going to write a prestige television show. I was going to write a series of novels that would be turned into a prestige television show. I was going to travel. I was going to read Middlemarch. I was going to learn how to sail? Sure. I was cash poor and time rich and I was going to spend it all on cobbling together a new life that would fit my ambitions with orthopedic comfort.

Instead I took up Hearthstone.

Hearthstone is a digital collectible card game made by Blizzard, the wildly successful video-game company behind Diablo and Starcraft and World of Warcraft. The object is to diminish your opponent’s health from thirty points to zero, using cards that represent damage-dealing spells (“Bane of Doom”) — I know — and minions (“Alexstrasza”) — believe me, I know — drawn from custom-constructed thirty-card decks assembled out of a library of hundreds — yes — of cards. Each card costs a certain amount of mana — believe me, whatever you’re going to say, I’ve heard it — your store of which increases in steps each turn. It’s a close descendent of Magic: The Gathering, which, if you’re my age, in middle school you played, or watched others play, or beat up the kids who played.

You don’t realize how much of your sense of self is bound up in how you use your time until you have a lot of it. An important part of myself had been propped up not on a title or a vocation but on a hundred quiet daily rites from which I was now an apostate: Slack chats, email exchanges, mid-afternoon coffees, bags of Haribo, glasses of warm vodka drunk after work at a friend’s desk. Hearthstone offered a comforting and familiar sacrament. At age eleven, I had, along with a bowl cut and several pairs of husky jeans, a small collection of Magic cards. I will never not want to spend time engaging a wizard (a sixteen-year-old in San Jose) upon the field (my laptop screen) of battle (with cards (digital cards)).

The thing about collectible card games, the neoliberal, twenty-first-century, rights-managed version of regular old playing cards, is that you need to have a lot of cards to play competitively. (“Play competitively” is CCG jargon for “have fun.”) What makes Hearthstone a particularly attractive proposition is that, unlike Magic, you earn those cards for free. Hearthstone requires a constant bench of available players for matches; to encourage people to play, it offers small rewards — cards, or gold you can use to buy them. A couple well-played hours a day and you can slowly accumulate a useful library.

When you get into the habit of forwarding your ambitions to the uncharted territory of When I Have The Time, they tend to assume the same unfathomable dimensions. You barely even remember what projects and ideas you’ve sent there, to the hic sunt horae edge of the map, and now you’re supposed to find and claim them? How do even you get your arms around something that big? Something you’ve been — supposedly — waiting to do for years? I decided at some point that the small but appreciable pleasure of casting Bloodlust on Lord Jaraxxus was more valuable than hacking through anxiety and neurosis in search of my unrealized, semi-mythical dreams.

I’m obviously kidding; it’s impossible to cast Bloodlust on Lord Jaraxxus. But this is what Hearthstone offers: An hour in the morning, an hour in the afternoon, three wins, fifty gold, another wing of Naxxramas, another pack, a Loatheb, a Savannah Highmane, a Midrange Hunter deck, and a small sense, in the unfolding temporal wilderness of unemployment, of accomplishment.

If the time echoing out in front of me felt vast and unmanageable, the dreams unwieldy and unconquerable, Hearthstone was the opposite. New, small, knowable, its skills masterable, its enjoyments easy to obtain. I played my games and worked my way up the ranking ladder. I watched serious streamers and read up on CCG strategy. I became proficient in the jargon — burn spells, three-drop, meta, Face Hunter, Control Warrior — the most exciting component of mastery. I limned the difference between aggro and control. I learned the virtues of card advantage — cards are your most precious resource; when you have more cards than your opponent, you have more options — and the meaning of tempo, which is, essentially, how efficiently you use the time you have available to you. (And you thought Hearthstone was a game about Harry Potter and the Sorcerer’s Dealing Shoe! Nerds don’t actually like dragons and elves and fantasy shit, they like competing strategies for allocating resources.)

Here’s the thing: After weeks of study and weeks of play, no matter which strategies I learned and tried, no matter which decks I constructed, no matter which cards I earned or bought or crafted, I wasn’t actually any good. I couldn’t ladder above level twelve in ranked play. I could talk a good game, and eke out a high-level win here and there. But I’m impatient. I suck at pacing. I have trouble getting tempo advantage. I make bad strategic decisions. I get nervous. I have trouble delaying gratification. Is why I’m bad at Hearthstone, I mean.

There’s a strategy in CCGs called milling. In Hearthstone the idea is that instead of doing damage, you make your opponent draw cards. Lots of them. Over and over. If you play a threatening minion — a creature that can attack a player — against a mill deck, your opponent won’t play his own minion to defend. If she’s a Rogue she’ll send it back to your hand with a spell called Sap; if he’s a Druid he’ll play a spell called Naturalize, which destroys it, but forces you to draw two cards. And once you run through your deck, you’re toast.

You don’t usually forget the first time you lose to a mill deck. Sometime near turn nine or ten, you realize that you’ve drawn through more than half your deck and converted almost none of it to lasting damage. Sixteen turns in, one of your longest-ever games, and you’ve played through an entire deck and have one minion in your hand. You’ve spent twenty minutes at the computer. You’ve been given every single card you’d need to win. Your opponent hasn’t really attacked once. And you’re still going to lose, badly.

But it’s a weirdly thrilling loss — the constant frustration, the shadowboxing, the way your greed for cards and eagerness for the win dooms you in the end. The sensation of steadily gaining card advantage (that is, opportunity) while falling behind in tempo (that is, your ability to use your time efficiently) is an odd and uncommon one. In Hearthstone.

At the end of October, a job fell into my lap more or less out of the blue. A good job, but a job that would take up a lot of my time — a job that would force me to defer more of my projects. A job I could do. A job I would be good at. I took it. What are my regrets? I should’ve learned to sail. I had the time.

New York City, December 28, 2015

★ There were clear skies in the west! And then, by midday, there were not, as loose clouds overhead brought back the gray or removed the blue. The clouds pulled together more tightly till the whole sky was dark and the river looked brownish. Nothing was any better than it had been. Soon enough it was worse. A rattling against the windows at dinnertime was too crisp to be rain; a hand stuck out the window to investigate came back in with a hard little lump of fallen ice sticking to the side of a finger.