New York City, January 7, 2016

★★ Morning was as harmless as it could be while still being identifiably wintry. The brown haze still lay on the horizon, and brown clouds grew up out of it. More clouds, thin and white, spread overhead. Neither the cold nor the light had any edge to them. The four-year-old let fall from his pocket one of the gloves that had replaced the gloves he had misplaced, but a passerby spotted it. Late afternoon turned pearly all of a sudden, and then clear gold light came bouncing off the north edge of the window. The clouds split into purple wisps that curved up and down in sine waves.

Foreign Bodies

by Muna Mire

I was eleven years old when 9/11 completely changed my conception of both the world around me and my place in it as a child of Muslim parents. It began slowly and then escalated: First, my parents quietly instructed us not to volunteer that we were Muslim in public. Then, a peer announced to me that he hated Muslims before the entire class. And, eventually, after being “outed” as Muslim, I began to go by my grandmother’s nickname for me, “Mimi” — something I had never considered doing before. I did that for the rest of my time in school, up until university. I erased myself, something which wasn’t hard to do as a Black Muslim.

It feels like we’re in an eerily similar moment now — one in which Muslim bodies, undocumented bodies, Black bodies, all ostensibly foreign bodies, really — are generating a lot of public anxiety, which is now structuring political discourse more forcefully than at any other moment in the last fifteen years. I wanted to find a way to interrupt what feels like history repeating itself by gathering some of the most insightful Black, Brown and Muslim people I knew to have a roundtable discussion on our mutual experiences in the post-9/11 age. Alok Vaid-Menon is a South Asian performance artist and one half of Darkmatter; Fariha Roisin is a writer and one half of Two Brown Girls; Amani Bin Shikhan is a writer and host of the whatsgood? podcast; and Asam Ahmad is a writer and the creator of the It Gets Fatter project.

What does the term “surveillance culture” mean to you? My first thought is of the state, but that’s not the only context. I think of policing, both of public space and private communications — directed with violence at Black, Brown, and Muslim bodies, particularly post-9/11. It’s important to look at the intersection of the former with the policing of poor, sex working, and gender non conforming bodies: What is and isn’t sanctioned? Who is and is not deviant? What form does this policing take? How does it impact people’s individual thought processes and behaviors? How have you personally experienced these surveillance structures? How did you navigate them?

Alok Vaid Menon: Surveillance culture isn’t just a specific set of state policies, isn’t just a moment or a trend — it’s a logic of colonialism and imperialism whereby all parts of ourselves must be rendered visible and therefore identifiable, categorizable, and ultimately containable. The only way that we come to understand and define ourselves is through a routinized and normalized ritual of public confession, articulation, and the production of public discourse, whether it be a series of identities that we attach to our bodies to become more coherent or an outfit that we wear to communicate who we are. The parts of us that we hold back from the mandate of visibility (and therefore the mandate of regulation) become seen as suspicious; the unfamiliar becomes the stranger, the unfamiliar becomes the terrorist.

Fariha Roisin: I think of all the times that I white-washed myself through the act of disowning my browness. This bodily performance is what I find a lot of people of color inhabit, and adopt, to feel safe. All the times I understood, inherently, that whiteness was better than whatever I was, I foiled myself in an outer layer of it to protect myself from abuse of the outside world. I felt like I had scales; I felt like I was completely unworthy of anything good. I absolutely disgusted myself on every level.

So, it’s sort of impossible that, now, I think I’m beautiful — but it’s taken me my whole life to get here. Like when I take a selfie, and I know I look good — I’m terrified of putting it out there, because what if I don’t? I think because I’ve always been a very intuitive person, especially as a kid, I was like a medium, so I would pick up on other people’s energetic mistreatment of me and introject it into my body as a form of remembrance, like a badge, and anytime I’d begin to feel good I’d tap into those feelings and remind myself: You’ll never be enough, Fariha. You’re not white.

I think I felt this way, also, because I didn’t have a lot of people of color as friends growing up. I mean Australia (where I grew up) is a wasteland of whiteness, and racism, so I didn’t really have a sense of togetherness that I feel exists in North America on at least some kind of level. I changed my name growing up so many times, preferring standard white names to deflect my strangeness. I hated people mispronouncing my name, and then joking about it, like,“haha Ferrari.”The way that I navigated so uncomfortably through my skin, always feeling outside of who I was, feeling in so many ways that my body didn’t represent the person I felt myself to be, as in a cool, quirky white person. Then, when 9/11 happened, I wasn’t even sure how to be a person, how to walk around in my super white school where I was already a weirdo because I didn’t read/watch/listen to what my peers listened to. I’ve always felt like such an alien, as I was always different in so many ways possible, so how could I even begin to learn and like myself? Being Muslim in a post-9/11 world, and actively identifying with that identity (even if it was a secret for so many years from my peers through my misplaced sense of self protection) has so much shame tethered to it. It was just another distinguishing aspect of how I was so wrong.

When people of color talk about their experiences of fear and ridicule, when they talk about their bodies — and trauma linked to those bodies, it’s so subversive. I think there’s nothing more powerful than to tell someone — someone who has actively resisted all that they are — that they are beautiful, or that they are seen, that they are valid in their identity. That they don’t need to be different to be powerful, to be smart, to be engaging, to be beautiful. That they are enough.

Policing is silencing. Policing is dismissing. Policing is denying. Policing is judgement. Policing is assuming. These are all the ways in which we’ve all been, and continue to be, policed.

Amani Bin Shikhan: The word surveillance instantly makes me think of Sydette Harry’s piece on the ways in which Black women are surveilled in every sense of the word, especially in the age of technological ‘freedom’ and shift of capital. As a woman who is equal parts Black, Muslim and immigrant, surveillance is not a new concept to my personal life or the lives of people who share any, or all of those experiences. I feel surveilled in the obvious, normalized gaze of the state by way of increased police presence in the most ordinary of spaces and in the incessant over-the-shoulder glances as I or my brother or my friend browse the halls of a given establishment; in the many instances where former professors and teachers have dropped my grade for choosing a topic too controversial, too strongly worded, too opinion-driven; and in the years that I burned my curls until they no longer bounced, only to wrap them as tightly as I could under my mother’s hand-me-down pashminas. I think of my middle school days, as I prodded at my soft torso, the droopiness of my cheeks and couldn’t, for the life of me, figure out how to live in my body.

Policing is a word that makes me feel tense even as I type it, as if speaking it into existence will take me back to the moments I felt the most small. Policing is a stripping of love, safety and rationale. Surveillance culture breeds a competitive race into assimilation, a sort of survival of the fittest. Except there is no real winner. We are all deviants; those of us from countries sprawled across the global South and the forgotten corners of the Western world, the indigenous, the poor of us, the educated of us, those of us with little access. The visibly Muslim, the visibly Black, the visibly Other. The insecurity of the state becomes the insecurity of the personal. We change names, we struggle to attain higher education in spaces that reject us, we dress more conservatively, and we shed the same fabrics. We build communities which internalize the same violent notions of purity, of homogeneity, of heteronormative patriarchy and every “ism” under the sun. We watch each other. And yet, we remain the subject.

Asam Ahmad: I think there are two ways of thinking through surveillance culture: surveillance as interpellation (Fanon), as rendering the subject within a delimited and highly circumscribed ontological space, and surveillance as rendering visible the very antagonisms that will be utilized for the exercise and expansion of state power (Foucault). It’s not just that the state’s surveillance mechanisms interpellate us as subjects in highly specific ways; rather, those same mechanisms create and then disseminate ideas of who and what constitutes the enemy of a state. I think of the ways in which the figure of the terrorist is so incredibly indispensable to the (permanent) state of emergenc(ies) in which most western liberal democracies now find themselves in. (And here, I don’t even need to point out that the very term “terrorism” has come to only signify Muslim terrorists — this is the default definition that now circulates in most people’s minds. The word “terror” itself thinks for us in the very ways power wants us to think about terror.) One doesn’t have to be a conspiracy theorist to note, for instance, that ISIS originates from the actions of the US military industrial complex. But it wouldn’t be far-fetched to say that if ISIS did not exist, it would need to be manufactured anyway in order for the state to function and for it to exercise its power.

What about non-state surveillance culture? Where does state policing of Black and Brown bodies give way to communities policing one another in private and in public?

Alok Vaid Menon: I think about gender — and specifically the policing of the gender binary — as the internalization of surveillance culture by the South Asian communities that I grew up in. I think about how, as a trans and gender non-conforming person, I have little space to talk about how the brunt of the gender policing that I have experienced in my life has come from my own family and communities, regardless of their gender. And these patterns of intimidation, of punishment for certain forms of visibility, of regulation of dress, speech, behavior, choice feel inextricably linked to the ways in which the State has taught us to contain, categorize, and colonize. I think the danger becomes when we discuss this type of gender policing without also addressing the ways that the State has and continues to police racialized people — we run the risk of demonizing our own and participating in a white supremacist narrative that immigrants and brown people are “more homophobic” or “more transphobic.” We need a more complicated way of ascribing agency and pinpointing blame: “Yes this happens to me, BUT…”

Fariha Roisin: I agree so much with Alok. There are so many limitations on bodies in South Asian/Muslim diasporas. The constant fate of being slut-shamed by so many people I was close to — including my mom and my sister — was mind-numbing. Ironically, I think that’s why I was pregnant at eighteen; I was never able to accept myself as a sexual being, so I punished myself through actively placing myself in positions of danger.

Something I think of a lot is how often my mom would call me up, crying, exhaustively calling me a whore, or other things, saying how she was embarrassed at an event because so-and-so had said something disparaging about me, oftentimes about how “loose” I was, or how “bad an influence” I was. When I figured out that it was through people spying on me over social media websites I felt so violated. In response, I would always tell my mother that there are two sides to every story (which never helped) but I refused to say things that I knew about what other kids were doing because I wanted to end that cycle. I wanted to end the cycle where women police other women. Or South Asians police other South Asians. We forget how subversive our own actions of kindness are. There were so many situations where I could have deferred to somebody’s kid doing something “wrong” but I never did, because it was besides the point. As Alok pointed out, there’s nothing empowering about shifting the blame.

Having said this: I’m not sure people understand how vital it is to be kind. Which, I know, sounds so Pollyanna, but I am so tired of people being engaged politically but bashing others for their lack of knowledge. That’s a form of policing that we don’t talk about. How in our own black and brown communities we are constantly surveilling each other. I think people make a lot of offhand assumptions about other people’s lives and we have to stop — especially if we don’t know them and the judgement only fits a narrative that we’ve created about them. It’s a reactive way of silencing, and it’s not beneficial to us, as a larger community. We have to be willing to have conversations with each other. We have to stop judging ourselves and others.

I often think of how my dad would tell me how colonialism was a way to keep us servile, to diminish our capacities. The British came and split India (and the world) into pieces; we started wars with each other; we began to hate others like and different from us. So, now, how do we heal from that experience? How do we actively begin processes of decolonization? How do we, collectively, move forward? I think it’s by lessening the hate in our hearts. The revolution starts when we begin to engage through empathy. I can’t say this enough: we have to stop policing each other. We have to be conscious of how we reproduce state violence in our own communities. I tweeted this earlier this year, ha!, but I do think kindness is where the real revolution lies.

These days, I have so many South Asian or Muslim women write to me and tell me that they’re grateful for my speaking out because I refuse to live a double life. But (!!!) it took me years of self-imposed violence to refuse to live a double life. I experienced years of abuse from my peers, from my mother, from my partners, from myself, to get here. We have to make ourselves feel safe in these spaces, and I don’t always feel safe in spaces that are ostensibly for me, and that’s frustrating, but more than anything it’s isolating.

We are all complicated. We all worthy of love. I am a Muslim woman, but I also have sex. I am South Asian, and I am also queer. These things are not mutually exclusive. So much of what I do, and continue to want to do, is to give language to the liminal states that we live in. Through narrative we heal; through creating a voice we understand that we are not wrong; by loving ourselves, and others, we become whole.

Amani Bin Shikhan: I struggle a lot with the concept of living a “double life,” not in the physical, social sense of my life but in the internal dialogues I have on a daily basis. The theory of intersectionality is still one whose basics I revisit often, not necessarily to remind myself of its definition, but to remind myself that it’s okay to be complicated. I joke with my East African and Middle Eastern friends that shame is a prerequisite in engaging in our multitude of cultures, whether the involvement is active or passive in nature. It’s something that I struggle to undo in my most private of thoughts. I’m not sure how much of my connection to culture — and by extension, everything else I believe to be true and important — is dependent on being “better,” or stronger than the Western influences that are assumed on my mind and body, or smarter than the perceived shortcomings of the culture and people who gave me life.

I have a genuine fear of speaking to my loved ones about conversations that I know would be seen as taboo — gender and sexuality, mental health, etc. — not because I doubt their ability to ~get it~, but because I know that it can be extremely difficult to confront the fragility of your ideological truths head-on. My parents are my best friends; they’ve taught me the importance of community, education and spirituality to keep me grounded in the most tumultuous of times. Even then, I know that there are certain subjects that I dread talking about in their presence. I’m not sure if it’s because I don’t want them to see me as their child, dismissive of their beliefs or if I don’t want to get myself into a situation where the brightness of their light dims. Maybe this fear is warranted, maybe I’ve imagined the worst possible scenarios and scared myself into believing them to be unwavering facts. This is the violence of surveillance; it births hesitancy in every facet of life. It’s a strange feeling to feel as though you are at odds with your own self, and yet, there I find myself time and time again. Surveillance vis-a-vis the state is a truth that can be researched, debated and organized around by people who feel its ramifications similarly. Surveillance within smaller bubbles dealing with conceptions of faith, culture, gender and every other intersection is harder because of its intimacy, its ability to break your spirit.

Asam Ahmad: We can also think of the ways in which “we” — progressives, citizens, subjects — internalize the logic of surveillance culture as the only way for us to articulate our “real and authentic selves.” When Alok speaks of the unfamiliar as the suspicious, it makes me think of the very notion of “coming out” and how that functions to police bodies and sexuality in highly specific and historically contingent ways. If visibility for trans women, for instance, means violence or sometimes potentially even death, what does it mean to insist that people “come out” in order to be legible to us as members of our community? What does it mean to ask people who are already multiply marginalized to further render visible their marginalization? And yet, at the same time, I can’t help but think of Junot Diaz’ metaphor of monsters as beings who do not have cultural and social mirrors to reflect their selves back to them. It’s as if we are caught in an impossible catch-22 from which there is no beyond.

Do communities in diaspora replicate the violence of state surveillance? Where and how? If not, what is the relationship between state norms and the surveillance culture in our communities? Alok’s thoughts on inherited colonial traumas are useful here, thinking about how people of color can replicate violent structures they inherit. Is surveillance culture a modern day colonial inheritance? How do we think about it? How do you navigate these violences?) How can we resist this within our own communities?

Fariha Roisin: Absolutely, just as the largest propagators of the patriarchy are so often women. This is what’s so damaging, that they replicate and enforce these impositions with so much tenacity; with so much readied intolerance. It’s important to accept and move on, without indicting our communities, that are still in the process of unlearning — as are we. It’s been so vital to me to connect with other South Asian/Muslims because it’s nourishing to be seen in all of your multitude of complexities. If we can learn to forgive each other, by embracing the other, we also teach others to. This is also how we really revolutionize culture: by learning to love others, truly, with no conditions attached.

Amani Bin Shikhan: I’m not sure that there is a definite answer to any of the aforementioned questions. To imply that diasporic communities — in my context, Black Muslim immigrant girls and women — are perpetrators of the state is to imply that they can exert a power comparable to the power of the state. Within diasporic communities, yes, there are definitely ranks of cultural and religious ideals: The Model Minority is rarely poor, or Black, or gender non-conforming; the Liberal Muslim is rarely Black or a woman whose multiplicity isn’t glossed over for the sake of posterity. The head of state, no matter how much they try, will not serve as more than a reminder of all that kills people who share their identifiers. At most, I would say my diasporic community does not mirror violence of the state, but rather is still learning how to not pass down the trauma they’ve inherited, as both Alok and Farhia have put beautifully, and Rianna Jade Parker of the Lonely Londoners articulates wonderfully in an episode of Cecile Emeke’s Strolling Series. Like I said above, my parents are my biggest teachers, and I see the ways in which they carefully right the wrongs of their parents and the practices or thought processes that they have come to find outdated. We are trying to survive. We are trying to build something worth surviving for. It’s important to value ourselves and our communities enough to see them as imperfect and love them still.

Asam Ahmad: I sometimes think of the ways in which for me, queerness has often worked oppositionally from race/ethnicity when it comes to public perception and my ability to navigate different kinds of public space. I find myself sometimes exaggerating my queerness to erase my monstrous or terroristic race/ethnic significations. It’s almost as if queerness becomes the repository of the west and of the state, in that it works against race. This is terrifying, and ahistorical, to say the least.

Photo by Pete

An Excerpt from 'My Struggle Book 7: Looks Who's Struggling Knau' by Karl Ove Knausgaard

by Karl Ove Knausgaard

For the eyes, sight is simple. When an image is in need of perceiving, it is swept through the lens of the eye onto a light-sensitive membrane. The patterns of light that form the image are then turned into neuronal signals and delivered to the central ganglia of the brain. What is being perceived though, is harder to say.

I did not and could not possibly understand this at the time, as the doctor was holding me upside down and I was looking at the enormous expanse of blue tiles with white lines that stretched out below me in a long web. The cold room sent waves of shivers around my pruned, naked body. When he first smacked me on my bare bottom I bit my lip silently. The noiselessness of the room was unbearable. When he hit my bottom again I could not help myself, I cried out. The tears came pouring out of me. No matter how hard I tried, I could not halt their advances.

My father sat in the corner of the room, wearing a cotton turtleneck and rubbing at the cleft in his chin. Out of the window behind him, geese flapped in a V formation towards the amber-hued setting sun. At the sight of my crying he turned dismissively towards the window and gazed at the snow flecked roofs of Stockholm.

Two stern looking nurses grabbed me from the doctor and tucked me away into a small plastic box, lined with a warm blue blanket. When they turned back towards me I felt a horror well up inside of me like an electrical shock.

“No, that’s a pink cap!” I tried to cry out at them as they spoke, but they did not understand the Norwegian word I used for cap, which was a slight variant on the Swedish word. I felt embarrassment growing deeply within me, like a well that had become cracked and muddied. They slid the bright pink cap onto my head and swaddled me in a cheap blanket. What is happening to me, I thought. The tears kept raining down my face. I tried calming myself by singing my favorite song, O Man Rivå, as the more robust nurse slowly pushed me out of the room.

At first I could only look at the bright florescent lights and drab white ceiling above me. I knew I had pooped in my diaper and I wanted to examine it, to see what my first poop looked like, but I was unable to move my arms, legs, or the rest of my body, and I also did not have the necessary brain capacity to understand the poop. Undeterred, I wiggled my butt into it a little.

The sound of the screaming around me was like the roar of thunder in the night sky. I could hear Gunnar, Knute, Inger, and Katja all making their own distinct, incessant wailings.

“Wailing does not help, of course,” I said to the nurse walking through the room, but she did not understand my Norwegian accent. I reached up to my pink cap and did my best to try and cover it with my tiny hands.

Geir was stationed next to me for those first few days before he left. He had on a normal, blue cap. There was something about Geir, even then. How he could fan his fingers and lift his feet. The way he didn’t struggle to use his eyelids. Once he turned to me and slapped his hand against the clear plastic of his box. Unable to move, I did the only thing I could, I rolled my eyes to the side and stuck out my tongue at him.

“Are you crazy?” he said.

Crazy?

How embarrassing!

No, no, no, no.

Not me!

I could not do anything but wiggle, so I wiggled.

“Oh Karl Ove,” Geir said. He turned away and practiced blowing bubbles with his lips.

A nurse came and took him away some amount of time later. She swaddled him in a blanket and lifted him to her plump shoulder. Before she left she turned towards me and held up Geir’s wrinkled pink face, wrapped in his cocoon.

“hej då!” She said in that chipper, enlightened Swedish way.

“Bye,” I said, rolling my eyes towards the window.

Nailed to the wall in a crude frame was an enormous replica of Caravaggio’s Sleeping Cupid. In between the moments I spent struggling to gain control of my most basic facilities I studied the painting. I was able to discern after a few minutes that it was not a real baby, as he was not moving and he was without depth. Once the two dimensional nature of the piece full displayed itself, I was able to consider it more completely. There was light in it from an unknown source of course, cast across his fat, small body. It was something that struck me as too symbolic. I turned to the opposite wall and noticed on it hung, oddly enough, The Hunters in the Snow, by Pieter Bruegel the Elder. I took the painting in for quite a while, appreciating its intricacy and beauty. There it was on the wall without the desperate need for meaning found in the artwork of the southern renaissance that eventually led to the more abstract works of the modern era, which sits as art for arts sake, divorced of any concrete reality. Glowing in the warm light of inspiration, I waggled my arms up and down searching for anything on which I might make a brief note. Realizing the feat I had accomplished, I kicked my legs up and down in pure ecstatic joy.

Wala! Wala!

I am Karl Ove!

My father entered the room with his long, strident steps. I immediately put my hands and legs down at my sides, keeping them tucked tightly against the soft wool of the blanket.

Looking down I noticed that I had shaken loose the bottom of my swaddling in all the excitement. Surely he would notice this, I thought. I searched around the small plastic box to see if there was another blanket I could use to cover the bottom of my feet. There was nothing. I stared nervously at the small holes that dotted the ceiling tiles above me. It was possible that I could swaddle the blanket around myself again, so that he would not notice. I would just need to teach myself a few more things about mobility. I shook each of my shoulders one at a time, first the left shoulder, then the right. With enough momentum I would be able to roll over and possibly tighten the blankets grip on me. Time was in short supply though, and he was approaching hastily. In a panic, I jerked my foot underneath the blanket as quickly as I could make it move, hoping he would not be able to tell the difference.

He looked down at me with his cold, icy eyes.

“Good morning Karl Ove,” he said.

“Goo goo ga ga,” I said. Realizing I could not speak, I was suddenly hit with a wall of shame. The tears began to flow again like a waterfall.

“Oh come now,” my father said. “Surely you are not crying over that?!”

O maaaaan Rivåååååå, I quietly hummed.

Translated from the fake Norwegian by Chris Messer, a fiction writer living in Brooklyn whose work has been featured in Post Road, No Tokens, The Fiddleback, and Radiator, and who currently works at New York Foundation for the Arts.

Previously: “The Home”

Fort Romeau, "Seventyfour"

Gorilla vs Bear calls this video “a mini sci-fi flick,” which is either an epic example of understatement or a sign saying my prime is so past that my references all register as referents now. In any event, please do enjoy this; everything Fort Romeau puts out is worth a listen. And for those of you for whom this clip evokes something else, here’s The Plugz with “Reel Ten.”

New York City, January 6, 2015

★★★ The morning cold immediately went through canvas sneakers. Trampled dog turds lay scattered loosely over the pavement, too stiff to adhere to it. The four-year-old rejected the concept of walking to school and had to be intermittently lifted and carried a few yards, puffy coat against adult’s puffy vest, to restart his feet. The blue of the sky was more washed out than it had been, and the horizon was brown. By midday, the sun, low as it was, was warm enough to allow the parka to hang unzipped. After the light had finished its quick afternoon passage — with a flourish of deep orange high on a building to mark the end — it was time to zip up again.

Bar Food Is Often Really Something Else

“We are at a bar somewhere near our office north of Times Square, and all I want are some potato skins, but all they have on the menu are mozzarella sticks and chicken wings and nachos, which are terrible if you ask me, at least compared to potato skins. Potato skins have everything you could ever hope for in a bar food — the crunch of the skin, the pull of the cheddar, the stink of the green onion, the chew of the bacon bits. A plate of potato skins and a pint of cold lager is the best pairing American cuisine has to offer. I mean that. I really do.”

— This is awfully good.

Keys, Not Cuffs

by Brendan O’Connor

This week, as temperatures in New York City dipped below freezing for the first time this winter, Governor Andrew Cuomo appeared to remember that there are homeless people — not only in New York City, but in cities around the state — and issued an apparently unprecedented executive order that people be forced off the streets and into shelters. “We have to get people in off the streets,” he said. “This is a state’s New Year resolution, a New Year resolution for the State of New York and in many ways, it’s keeping with the spirit of the holiday season, right?…It’s about love. It’s about compassion. It’s about helping one another and basic human decency.”

The announcement came as a surprise to Mayor Bill de Blasio, who, in November, after failing to make a deal with the governor on a joint fifteen-year plan to build supportive housing for the homeless and mentally ill, announced that the city would fund the development of fifteen thousand units of supportive housing without the state’s help. (“It’s clear that the Mayor can’t manage the homeless crisis and the State does intend to step in with both management expertise and resources in a plan to be released in the State of the State,” a Cuomo spokeswoman said in a statement.) The mayor followed this up in December with the introduction of the ominously named HOME-STAT program — a reference to the NYPD’s COMPSTAT program. “We’ll have the most up-to-date, specific data on the street population we’ve ever had,” de Blasio aid. “And we’ll perform rigorous analyses of that data to determine what people need, what’s working, and what’s not — helping us take important steps to keep street homelessness down in the future.” According to the New York Times, Commissioner William Bratton, long frustrated by the fact that it is not illegal to be homeless, added that the NYPD is investigating whether it would be possible to modify the city’s laws to allow police officers more leeway to force homeless people out of certain areas “if we are able to frame it in a way that the courts don’t overrule.”

“This new program is just more of the same,” Jesus Morales, a member of the housing advocacy group Picture the Homeless, said in a statement provided by a spokesman the day of the mayor’s announcement. “More case workers, more cops — that does nothing for me. Meanwhile, the cops are treating homeless people like dirt, every day. That’s the problem the mayor needs to fix.” (Also, the city already has a so-called Code Blue policy in effect, mandating that shelters allow anyone access during freezing weather.) The next week, Morales filed a notice of claim with the comptroller’s office — the first step in filing a lawsuit he and two other homeless New Yorkers are bringing, with the help of the New York Civil Liberties Union, against the city, the NYPD, and the Department of Sanitation. The three men were sleeping outside a school building in East Harlem when, around 5 AM, police officers and “unidentified individuals in white uniforms, believed to be employees of the New York City Department of Sanitation” woke them up and told them to leave. “One of the officers kicked Mr. Morales,” the notice claims. “Within minutes of their arrival, the Department of Sanitation workers placed personal property belonging to individuals in the second group in garbage trucks and operated the trucks’ compactors to crush the property.”

Altogether, $250 worth of property was allegedly destroyed: Morales’ birth certificate; his social security card; two pairs of sneakers; two sweaters; five pairs of pants; seven t-shirts; two packs of socks; four packs of boxers; one jacket; a shopping cart; soap; toothpaste; a toothbrush; lotion; and deodorant. Morales will sue for unlawful seizure, deprivation of property without due process, intentional infliction of emotional distress, and negligent infliction of emotional distress. (Some of the interaction was caught on school surveillance cameras.) At a press conference announcing the claim, Morales and other homeless people spoke about their experiences both in shelters and with the police, on the street, and speculated that the tactics being used in East Harlem are, essentially a pilot program for HOME-STAT, which will now be implemented around the city. Morales spoke in Spanish, with a translator. “I gotta speak from my heart, bro,” he told me afterwards, lighting a cigarette. “It’s too much.”

It is worth noting that living on the street, even while being targeted by the police, is preferable to living in a shelter — at least for some people. “I have been on the street the last six months,” one of the claimants joining Morales in his suit, Floyd Parks, said in a statement. “I feel safer there, cleaner, than I did in shelter. I lost valuable property in the shelter system. The Mayor should fix up all these vacant buildings and lots over here for the homeless. We need somewhere permanent to stay. Shelters don’t help.” The mayor, at least, acknowledges this. “The shelters absolutely have to be improved,” he said this week. “That’s part of what we’ve invested in. Look, when I came into office, for years our shelters have been sub-standard.” According to Politico New York, de Blasio claimed that “seventy to eighty percent” of shelter violations according to a report he ordered last year have been cured, adding that “hundreds” of peace officers now patrol the city’s shelters. “But we’re continuing to work on every one of those violations. So, we’re committed to improving the quality of our shelters.”

Last month, though, Comptroller Scott Stringer issued a report on an audit his office conducted that had found one or more hazardous conditions in eighty eight out of one-hundred-one randomly selected apartments in city-funded family shelters. One hundred fifty five family shelters house some twelve-thousand-five-hundred families around the city. “No one wants to be in a shelter,” PTH member Turhan White said in a statement. (On Wednesday night, 58,086 individuals, including both families and single adults slept in homeless shelters.) “Do you have to go through a metal detector to get into your apartment? Do you have someone in your house telling you what time you have to go to bed?” Heightening the policing of shelters is only going to further alienate homeless people who already fear (or are at least suspicious of) representatives of the state.

(The Department of Justice recently filed a statement of interest in a lawsuit in Boise, Idaho, arguing that Eighth Amendment protections against cruel and unusual punishment render laws which criminalize homelessness unconstitutional: “When adequate shelter space exists, individuals have a choice about whether or not to sleep in public. However, when adequate shelter space does not exist, there is no meaningful distinction between the status of being homeless and the conduct of sleeping in public. Sleeping is a life-sustaining activity — i.e., it must occur at some time in some place. If a person literally has nowhere else to go, then enforcement of the anti-camping ordinance against that person criminalizes her for being homeless.” In 2014, according to the DOJ, forty-two percent of homeless people lived on the street — around a hundred and fifty-three thousand individuals around the country on any given night.)

Andrew Cuomo, though, should certainly know better than to pretend that shelters are anything resembling an answer to the homelessness crisis. In 1991, Cuomo, then head of the non-profit Housing Enterprise for the Less Privileged (HELP), was chosen to lead Mayor David Dinkins’ Commission on Homelessness. A year later, the commission recommended sweeping, systemic changes to the city’s shelter system, including the introduction of rent subsidies to help people pay for housing and increased services for those struggling with addiction and mental illness. If you’re curious about the efficacy of such a model, just ask the men in blue jumpsuits at work around the city.

“The homeless problem says to each of us, ‘How do you believe we should treat one another?’” Cuomo said on Tuesday. “We as New Yorkers have to admit the truth. The problem is getting worse. It’s worse than it has been in years. It’s unacceptable. We will not tolerate it. It must change. We’re not leaving our brothers and sisters in the street to freeze.” So long as the emphasis is on shelter, however, and not housing, that is exactly what we are doing.

The Origin of Tech Species

by Elmo Keep and James Douglas

Elmo Keep: Greetings, fellow meat human. So good to connect with you over the networked machines.

James Douglas: Yes, Elmo. *Secret handshake* 01001100 01101001 01110110 01101001 01101110 01100111 00100000 01100110 01101111 01110010 01100101 01110110 01100101 01110010 00100000 01110111 01101111 01110101 01101100 01100100 00100000 01110011 01110101 01100011 01101011 00101100 00100000 01100001 01100011 01110100 01110101 01100001 01101100 01101100 01111001 00101110 00100000

I’m interested in understanding something about the genealogy of the ideas that make up the cosmology of Tech Thought today, since that industry continues to have such far-reaching social and political effects. Your recent Verge piece is very diligent about providing this sort of historical insight! Especially, re: how so many intellectual and research pursuits in current tech culture — and, with this transhumanist candidate for President, politics — can be traced back to the Extropians and their mailing list. These are/were an interesting bunch, it seems?

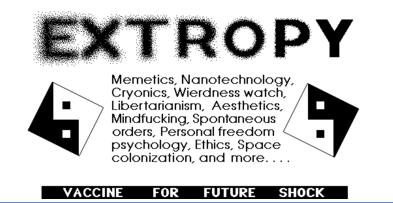

EK: Transhumanism and contemporary techno-futurism are closely interlinked, and transhumanism is deeply influenced by sci-fi, though more so what might be called hard sci-fi — cyberpunk, particularly (Joshua Raulerson has a great book on this, Singularities). The most influential set of ideas in modern transhumanism came from Max More (Max O’Connor) and T. O. Morrow (Tom Bell, a lawyer) in the form of Extropy. Extropy was an ad-hoc philosophy they cobbled together which positioned itself in opposition to entropy; human beings would overcome death and decay through technology. It was extremely hostile to the State, to governing systems of all kinds. Particularly to paying taxes. It was staunchly Randian Libertarian, individualist and techno-utopian in its outlook. It was also advocating for what is basically eugenics: a class/race of superbeings with augmented hyperintelligence and physicality who through these enhancements will be literally unstoppable and colonise the universe.

Extropy began as a zine, Vaccine For Future Shock, later rebranded the Journal of Transhumanist Thought, and was then an institute (since closed because the goals of Extropy, they decided, had been realised by 2006.) The zine soon migrated to the mailing list and is still active today. It exists in various dumps of archive sections but there isn’t a complete archive anywhere — a lot of it is lost to the offline wilds and dead links, which is itself not a great indicator for their hopes of a fantastic future filled with currently unimaginable technologies.

The Extropians had — what can look to be from here — an undue amount of influence on tech culture and industry of the last twenty-five years. This is explained a little by the nascent form of the web at the time. There were comparatively few mailing lists to belong to then — pre-Reddit and giant message boards — so it’s not unusual that a bunch of people congregated on what was one of the most well-known lists at the time, in the early nineties. But it was very much a scene (they loved to throw conferences), and what is unusual about it is where a lot of those people ended up, and what their connections were, and what motivated and informed their points of view. It was also unusual in that people were using their real names there, by and large. Weird not just because anonymity and the fight against it would come to dominate the social web, but because the Extropians were extremely concerned with privacy, cryptography in particular.

Original ad for the zine in bOING bOING, then also a zine.

Anyway, details!

JD: I guess that’s the benefit of taking the epochal view, right? You never need to sweat the small things.

EK: Quite. The Extropian list was home to the lengthy discussion of the passions of transhumanists. These included everything from dropping acid and polyamory to space exploration, physics, philosophy and gene therapy. It was all pretty outre and very much part of the Bay Area’s existing counterculture lineage. It was about blowing minds, dude (they had a special handshake). There were elements of transhumanism that were talked about more than others on the list. Of special interest were science fiction, cryogenics, cryptography, anonymous digital cash, nanotechnology, the Singularity, artificial intelligence, mind-uploading, smart drugs, immortality, cybernetics, robotics, and how much the Government sucked.

No one outside this tiny clique really knew much about the Extropians or who they were until Ed Regis profiled the founders for one of the first issues of Wired. “Meet The Extropians” is a portrait of a moment in time so quaintly dated it’s a weird sort of curio now.

JD: The Extropian party scene described by Regis sounds positively loose. I have my doubts that hanging out in suburban hot tubs is a particularly healthful pursuit (because, to me, they are disgusting incubators of filth) but I suppose if you expect to be living forever a little Legionnaires’ disease won’t bother you. Will cyborg bodies get pruney skin during bath time?

EK: Well, physical perfection and ideals of beauty were very important to the Extropians, so wrinkled skin of any kind at any time would have been thought an aberration.

JD: Here’s a quote from the Wired Extropian piece:

The overall goal is to become more than human — to become superhuman, “transhuman,” or “posthuman,” as they like to say — possessed of drastically augmented intellects, memories, and physical powers. The goal is a society based on freely chosen social arrangements, on systems of self-generating “spontaneous order,” as opposed to massive legal structures imposed from above by the State. And the goal is to gain as complete control over the physical universe as is compatible with natural law.

This notion of “spontaneous order” is an interesting one, not least because it is so persistent, and pervasive. There’s neat stuff on this train of thought in episode two of Adam Curtis’ All Watched Over By Machine of Loving Grace, where Curtis takes a look at Californian technologists’ obsession with networked societies. He argues that the conviction that digital technology could produce decentralised power structures was inspired by ecological theories of environmental “balance” that were actually totally bogus. He concludes, by analogy with the collapse of hippy communes in the seventies, that decentralised power structures tend to conceal hidden hierarchies, no matter how hard they pretend to steer toward a “natural” equilibrium.

EK: I mean, if video games can’t unite people in a self-organizing utopian social order, then what can?

JD: What is the sharing economy but this ecological fantasy in a contemporary guise — an ostensibly “free” market of consumers and service providers, more or less overtly structured by putatively neutral mediators like Uber or Airbnb? I guess it’s convenient that “unregulated” markets not only cater to the fantasy of the superpowered (economic) actor, but also open up a huge structural chasm in which businesses can insert themselves and extract profit. It’s almost as if, maybe, the techno-idealism of this sort of thinking conceals, barely, a mess of fairly quotidian capitalist imperatives?

EK: Quotidian capitalist imperatives paired with “on demand” efficiency. I think in the case of contemporary SV, this is particularly insidious, and not even vaguely concealed. It’s putting two terrible human impulses together and stoking them to the point where they are now the driving factors of tech innovation: How can I get something as cheaply as possible and as close to immediately as possible, regardless of how many people get screwed in that process? It rewards both intolerable impatience and being a cheapskate. How terrific that this is where we have evolved to.

But like you say in your piece, anything can be recast as heroic if you spin the right origin myth, preferably one well-versed in Star Wars. I wish I could find where I read it, but I read someone on Twitter a while ago saying that the on demand economy can be summed up as, How can I get someone to do what my mother used to do for me? (My laundry, bring my food immediately, pick me up from wherever I am.)

JD: But, also, infantilization grossly reconceived as rationalism: as though making things faster, easier, and more immediately gratifying were the only pursuit worth any mental energy. This confusion of intellect with total selfishness maybe helps explain why when these folks start to talk about creating genuine artificial intelligence they immediately start worrying about it killing everybody. Like, whoa there: Speak for yourself.

EK: The obsession AI researchers have with what they perceive to be “rationalism” is hubris-laden (harking back to extropian ideas of overcoming natural laws with rational thinking.) They are convinced not only that an AI that could spin out of control will exist, but that only they will be able to prevent it from killing everyone. And the way they propose to do this is to somehow program it in accordance with these utilitarian principles of “rationality” at its core. This is how they assume to impose a moral framework on a machine: If it only ever makes “rational” decisions, then it will only ever be helpful. Rational according to who? According to what set of principles? Agreed on by whom? “Helpful” how? Apparently anyone who doesn’t understand these largely mathematical modes of decision theory is not qualified to have any say in this — a machine that is meant to be able to mimic the intelligence of a human being. This again comes back to the fantasy of self-organising technological structures being able to make better decisions than actual human beings, as if the mess of society could just be done away with if only there were powerful enough equations or algorithms. Equations authored by right set of geniuses.

JD: Another “rational” solution. Of course.

EK: The ways in which this assumes extremely (relativistic) simple solutions to unfathomably complex ideas of social order is terrifying. These are the people who have appointed themselves the only ones smart enough to understand any of this — their own suppositions. Nick Bostrom spearheads a great deal of it, which he started on once he joined and spent years on the Extropians mailing list, founded the World Transhumanist Association, and then established a series of think tanks and university departments dedicated to these extremely flimsy transhumanist visions of society. Only now they have actual money behind them and significant coverage in the mainstream press.

JD: Also terrifying is not just the fact that the “solutions” are so simple, but the fact that they are so intellectually tenuous, and yet so still resilient — they keep cropping up in fun new, extremely influential places.

EK: These ideas have been around for a long time. In Tim May’s hundred-and-sixty-thousand-word Cyphernomicon (all in red text on black! #rememberthe90s), which he wrote after becoming flush with a fortune made at Intel and which was originally conceived as a sci-fi novel, he puts forth the idea of cyberspace, as it was then called, being a lawless zone in which people could pursue whatever freedoms they wanted, free of government interference or surveillance. The Cyphernomicon was a formalisation of everything happening on the Cypherpunks mailing list, which had a very significant overlap at the time with the Extropians list. It also alluded to a sci-fi novel by Vernor Vinge (who first posited the Singularity), True Names, which was a fictional vision of what this internet could be. (Neal Stephenson’s Cryptonomicon was a kind of allusion to the Cyphernomicon — a speculative novel about cryptography, offshore data havens and digital cash where all kinds of experimental research projects are possible. It was compulsory reading for all PayPal employees.)

A sacred cypherpunk tenet was “cypherpunks code,” as in they actually implemented these things, and worried (or not) about any consequences later. This is where PGP and TOR came from — and eventually what became Bitcoin and Wikileaks also came out of that list. Thiel’s mantra, “Don’t Ask For Permission, Ask For Forgiveness,” as widely adopted now in SV start-up culture, is just an updated take on “cypherpunks code.” It’s the same impulse, to circumvent existing structures through technology (break shit), and worry (if you do at all) about the consequences later. The very staunch Libertarianism that is so alive in Silicon Valley now has this long, odd pedigree.

JD: It’s sort of wild to think about how close knit and promiscuous the Venn diagram of Extropian-associates and contemporary tech financiers/developers/thinkers is — and wilder still when counting in the circle of related culture industry operatives, like Stephenson, or employees at Pixar and Lucasfilm. These kinds of connections honestly get my brain churning. I recently read Foucault’s Pendulum, by Umberto Eco, which is about a guy who is so obsessed with uncovering the contours of a half-imagined conspiracy that he ends up inventing the most complete, most plausible version of that conspiracy yet, and all its adherents hunt him down, convinced that he possesses Secret Knowledge (I think it’s a parable about epistemology or something).

EK: Conspiracy theories are so fun right up until people start believing them.

JD: Anyway, I feel like it’s easy to dip into a paranoid frame of mind when thinking about the many interrelations between the tech industry, and the culture industry and the thinkers that cross over and speak to both. I don’t want to ascribe too much weight to the associations between them, but they paint a very interesting picture? Basically, what I’m asking is: Is there a not-so-secret cabal of science fiction geeks (and hot-tubbers) trying to change the world for the worse, using technology?

I like the little timeline of Transhumanism you spool out in your Verge piece, which includes the 1931 appearance in Amazing Stories of “The Jameson Satellite” by Neil R. Jones, about a man whose frozen brain is rescued by cyborgs and installed in a robot body. That story, you write, went on to inspire Robert Ettinger, founder of the Cryonics Institute. (You also mention “The Altered Ego,” by Jerry Sohl, as an early instance of mind-uploading in fiction.) In my Lucasfilm thing, I wrote that “The history of the tech industry can, in a way, be traced by its inspiration from and adoption of the idealist nostrums of traditional science fiction, like artificial intelligence, virtual reality, and extended lifespans,” which is a pretty loose claim, to be honest, but also, I hope, one that suggests something reasonable about the visible interplay between science fiction writers and their audiences, and futurists, and techno-prophets, and, now, tech developers and VCs.

And, okay, so my use of the “geek” label is very tendentious, but it maybe fits my image of the kind of person who is a little too immersed in the emotional comforts and power fantasies offered by science fiction (or fantastic fiction, or whatever). Of course, perfectly sensible adult humans can be intellectually engaged by sci-fi — and emotionally rejuvenated by heroic stories like Star Wars — but a person who actually strives to live within the sentimental frameworks of fantastic fiction by actualising its technologies into everyday life is maybe in the grip of some kind of arrested development?

EK: I’ve never actually seen a Star Wars film. I made a very bad mistake in trying to correct that by watching A Phantom Menace first, which was… an error. I thought you were meant to watch them in that order! In any case, I really love how excited people are about The Force Awakens; it seems like it lived up to all they hoped it would be. Which would be so nice, for something you have very fond memories of to actually match up to your hopes. Not nice enough to build your technocapitalist Galt’s Gulch around, though.

JD: I keep thinking about Thiel’s essay for Cato Unbound, in which, among other things, he proclaims his own heroic ambitions for tech funding. In it, he writes “I remain committed to the faith of my teenage years,” by way of explaining his dedication to “authentic human freedom.” I take it that this is meant to seem like a principled stance, but it’s also kind of embarrassing to see an adult admit that? Adolescent perspectives on “freedom” (or, well, middle-class, white, adolescent perspectives) may or may not be meaningful, on occasion (even a stopped clock is right twice a day), but imagine taking them seriously as a basis for a real-world social and technological program!

Aspects of the neo-reactionist political project (which has been linked to Thiel) seem palpably to run along the same lines, to me: a childish vision of liberation denuded of any actual social responsibility, or any ability to think clearly about the welfare of others. Representative democracy has some problems, but to wholly reject it in favor of autocracy seems a little like the perspective of a small child unwilling to share its toys or lose its comforts. And so, we have projects like Seasteading, where you get to live basically in Waterworld and never have to do what your parents tell you to do, or Alcor, where you never have to really say goodbye to anyone you love.

This juvenility could seem kind of cute, or at least harmless, except that kids are actually terrible at thinking about the needs of others, much less making considered moral decisions. In your piece you argue pretty convincingly that transhumanism is something like a diversion from actual, present political, social, and environmental concerns — which I think suggests something true about how the kind of mentality we’re talking about can end up missing the forest for the trees. Do you think the transhumanist movement is kind of, at its core, unethical?

EK: In the same way they seek to be post-human, transhumanism also seeks to be post-ethics, via technology. If you look at the extreme end of transhumanism, the Extropian end, which is really where the contemporary strains of it came from, they saw ethics as completely irrelevant. They advocated for what they called anarcho-capitalism, where, through technologies like digital cash (untraceable digital cash was absolutely key to this mission, the development of what became bitcoin was the number one goal of the Cypherpunks, and feverishly discussed among Extropians too, almost above privacy and personal security), state financial institutions would be made obsolete and dismantled totally. PayPal grew out of these same impulses, to code a digital payments system that couldn’t be monitored by government regulation. It was often pitched as being a very noble goal — absolute privacy from the intrusion of scrutiny–but what it also enabled was hiding assets and avoiding taxes.

So this, I think, ties pretty directly into what you’re saying; this brand of Libertarianism is basically, “don’t touch my stuff.” Don’t take any of my money to give to other people, why should my success pay for poor people’s welfare? I should not have to be part of any collective, just let me live in my own little castle. I don’t want to share my toys.

JD: If you spend enough time rationalising your own selfishness and inflated self-image it’s inevitable that you’ll end up committed to some outré political positions.

EK: This was a mission to wholly transcend the State, which they saw as an oppressive tool. Not in the sense that its capitalist expression enslaves almost everyone, most egregiously minorities, but oppressive in that it made them pay tax. You see this very much alive in Silicon Valley today, whether it’s giant corporations hiding their assets to avoid taxes, “philanthrocaptialism” as practised by Mark Zuckerberg, or Peter Thiel’s dream of “changing the world” through circumventing regulation altogether by literally offshoring experimental research and then worrying about the consequence for society later. This is taking “break shit” to a whole new level, “shit” being “what does it mean to be human?”

JD: Here’s where that “changing the world for the worse” suspicion comes in. Re: that “break shit” mentality, in one of his essays, Max More proposes that a key Extropian mode of thought is “Dynamic Optimism”: “an active, empowering, constructive attitude that creates conditions for success by focusing and acting on possibilities and opportunities.” Which is just an incredibly revealing point of view, not just because that principle is so capitalist to its core (the market abhors a vacuum, after all), but for how it dresses up an disinclination to anticipate adverse consequences as a virtue.

EK: Everything was beautiful and nothing hurt.

JD: Not sure how your short-term wants will affect future generations? Don’t worry; just do it (that cypherpunks code, again). It’s interesting, too, how much More’s five steps for Interpreting Experience Positively anticipates aspects of the current tech industry’s resistance to criticism that John Herrman has written about here recently (I mean, step one is actually called “Selective Focus”).

EK: It is in this way an incredibly infantile mindset: You are so special and unique and so much more intelligent than everyone else that the rules do not apply to you. Everyone else is a luddite idiot stuck muddling through their archaic democracy. And that’s where you end up at neoreactionism and its “Sith Lords,” as you point out.

JD: It’s hard not to feel a bit gently sympathetic when tallying the effects of this arrested development/techno-utopian heroic fantasy. Except, apprehensive, also, given the billions of dollars and the cultural and technological resources at its adherents’ disposal.

EK: It seems like the worst thing that could ever happen to a person would be to never mature intellectually or morally or emotionally beyond adolescence and then somehow come into incomprehensible amounts of money.

JD: Not so good for the rest of us, either.

James Douglas and Elmo Keep are just two meat humans with meatish concerns and worries.

Gif via MachinePix

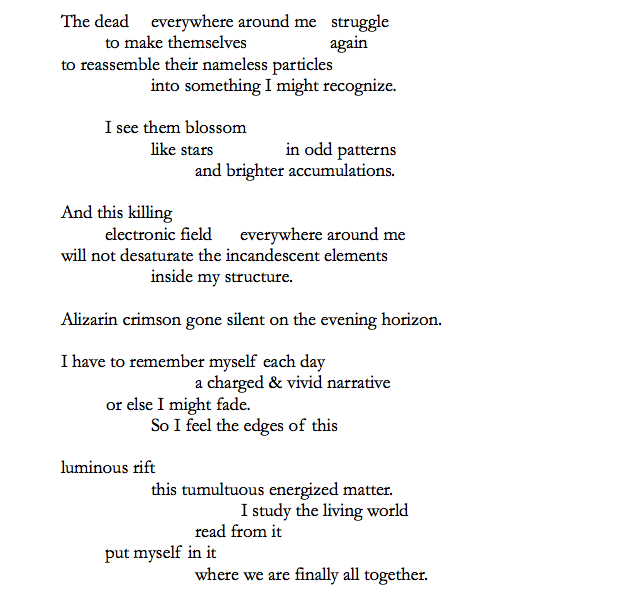

A Poem by Nate Pritts

by Mark Bibbins, Editor

A Vision in Winter

Nate Pritts is the author of seven books of poetry. The newest, Post Human, is from A-Minor Books. The Director and Founding Editor of H_NGM_N, an independent publishing house that started as a mimeograph ‘zine, he lives in the Finger Lakes of NY state.

You will find more poems here. You may contact the editor at poems@theawl.com.

The Year in Weird New Frogs

The number of amphibians has been declining disturbingly rapidly over the past few decades, due to all the usual suspects: habitat destruction, climate change, pollution, pesticide use, introduced species, weird new fungal diseases. Being a widespread and effective seed distributor as well as a food source for many larger animals, the disappearance of the frogs is a huge and very un-cute problem. As a result, funding and interest in discovering and theoretically protecting frogs has increased quite a bit. More and more scientists and researchers are tasked with heading out to find new frogs. And it turns out that if you go looking for new frogs, there’s a pretty decent chance you’ll find some new frogs.

Last year was a banner one in frog discovery. I’m not sure exactly how many new species were discovered or described, because scientists don’t all use one spreadsheet where they write down the frogs they find, but it seemed like you couldn’t go a month without reading about some great new frog. At least I couldn’t. Here are some of the very good frogs that we now know about.

Diane’s Bare-Hearted Glass Frog

Glass frogs are so named because they’re sort of translucent and delicate-looking. This one was found in Costa Rica and got a lot of attention because it looks like Kermit, who is technically a puppet and not a frog. Frogs have semi-permeable skin and can use their skin as a secondary breathing apparatus; Kermit’s skin is green cloth and he does not breathe. There are also other differences.

Mutable Rain Frog

This is a very small frog found in the Ecuadorian mountains, and is an especially good frog because it’s capable of changing its skin texture from bumpy to smooth. Basically it can look like a toad or a frog depending on how its skin looks. (For what it’s worth all toads are frogs; the word “toad” is an arbitrary and not very good grouping of some frogs based on warty-looking skin.)

Teresensis’ Bromeliad Treefrog

Found in southeastern Brazil, this very small frog lives in the pool of water created by the cupped shape of the leaves of a bromeliad plant. It is extremely cute.

Noblella madreselva

Also found in South America, this Peruvian frog has a bandit-like mask, which is a very good look for any animal, but is probably more notable for its size: about as big as a regulation-sized jelly bean.

Seven New Brachycephalus Species

Oh boy!!!! Scientists exploring the cloud forests of Brazil found a whopping seven new species of related frogs, all of which are tiny, some of which are bright orange and very poisonous. Do not eat these frogs. Right after the presence of those seven frogs was announced to the world, a Brazilian researcher followed by announcing his own new Brachycephalus species. This one looks very angry.

Incredibly Weird Clawed Frogs

Clawed frogs are native to sub-Saharan Africa and are weird pretty much always: They’re these bizarre flat-looking frogs with eyes on top of their heads and big claws on their back legs. They also will give birth when injected with the urine of a pregnant human woman, which, like, what? What a weird freakin’ frog.

Six new species of clawed frog were discovered this year, and they are extra weird because their DNA is polyploid. Humans, and most other animals, are diploid, meaning we snag half our DNA from one parent and half from the other. These frogs, for whatever reason, snagged the entire chunk of DNA from both parents, and some were even found to be the second or third generation to do that, meaning they have the complete sets of DNA from grandparents as well. Again: weird frog.

Atlantic Coast Leopard Frog

If you grew up basically anywhere on the east coast, this guy probably looks familiar: The leopard frog is the most interesting frog we have. Its discovery is one of those not-as-exciting things where scientists look at the DNA of a population of an animal and decide it’s different enough from the rest of the populations of the animal to qualify as its own species. What this means is that if you had had elaborate DNA testing equipment as a kid you could have discovered this frog and named it after yourself. But you didn’t. Now you might never have a frog named after you.

Brazilian Hylid Frog, or Greening’s Frog

The Brazilian hylid frog is the weirdest frog discovery of 2015. It is the world’s first known venomous frog. You might be saying, hey, what about those cute poison dart frogs, they’re brightly colored and aren’t they very dangerous? And yes they are, but they’re poisonous, not venomous: You get sick when you eat a poisonous animal, but a venomous animal can actually sting or bite or otherwise actively inject you with venom. This frog, native to the coastal areas waaaay out in the central-east part of Brazil, has a bunch of spines on its lip, and actually scraped the scientist who discovered it, leaving him a terrible pain for a few hours before he recovered, making a firm note not to grab the mean frog next time. The Greening’s Frog, interestingly, is both venomous and poisonous: it secretes poison from its skin, and can also inject venom with its spines. Very good, very scary frog.

The reason frogs are being discovered so often now is undeniably a depressing one: The IUCN, which is the organization responsible for deeming species “threatened” and “endangered,” estimates that somewhere between nine and a hundred and twenty-two species of frog have gone extinct since 1980, and that around half of known species are in significant decline. But hopefully the discovery of new frogs could have some miraculous effect, maybe alerting governments that it’s not just furry mammals that need protecting.

Another good frog is the Pignose Frog.

Photos by Luiz Fernando Ribeiro, Katherine Krynak, Rodrigo Ferreira, Vanessa Uscapi, Luiz Fernando Ribeiro, Vaclav Gvozdík, Brian Curry, and Carlos Jared, respectively