HÆLOS, "Oracle"

Does it seem like it’s starting to stay lighter later? Even for an extra minute or two each day? For me it’s always dark, so I wouldn’t know, but I hear talk from people who claim to have seen it. We’ve still got the bulk of winter to get over, so whatever you need to tell yourself to make it through is okay by me. Anyway, I don’t know a thing about this band, but gosh this track sounds good. Enjoy.

New York City, January 11, 2016

★★★★ Sharp, low sunbeams pierced the usual dimness of the hallway, coming under the doors of east-facing apartments. The doorman declared that it was getting colder, not warmer, as the day came on. By early afternoon, the wind on the avenue growled past the ears and sent a tear trickling backwards along the zygomatic. The sun was bright and attractive; it made a blurry glitter in lowered eyebrows; but it was no help against the cold. It was time to hide in the warmth of the apartment lobby for the five minutes of slack in the schedule between the walk back from preschool and the third-grade dismissal. All the gloves made hand-holding cumbersome, till it proved easier to impel and protect the children by pinching a fold in the puffy upper arms of their coats. There was nothing in the cloudless sky for the sunset to get purchase on, but grids of scarlet light flared from building to building below.

Book Funny

Some good news: Brian Hennigan’s Patrick Robertson: A Tale of Adventure, a novel I have been banging on about for fifteen years as one of the funniest I have ever read, is available for the first time in an American edition. The story of a salesman kidnapped in a case of mistaken identity, Patrick Robertson shows that the skills that spell success in business are the same that psychopaths use to work their will on everyone else. Filled with such inarguable truths as

Failures are, on the whole, interesting people. Failures have gambled and lost, battled and been defeated, been conned, swindled, have dived and bobbed before realizing that the world has not been made for them to succeed in. They end up as small-town barkeepers, second-hand (but not antiquarian) booksellers, self-employed business consultants. Cooking is one of the skills common to most failures. For conversation they have the inexhaustible arsenal of a life of strenuous activity thwarted by bureaucracy, public indifference, or ‘other people’.

and

Alcohol is not the answer to all our problems. But if one removes from one’s life the problems that cannot be solved with alcohol, the path is clear. Families are a particular nuisance. Get rid of them as soon as possible. With them go all the other responsibilities which require sobriety: pets, in-laws, other parents, Sunday mornings.

Patrick Robertson has the wisdom we need in these troubled times. There are very few good books written about business; there are even fewer funny ones. Do something nice for yourself and buy this book.

The (Non-Stick) Chemicals Between Us

by Kieran Najita

The world is a horrible place filled with terrible things; some we embrace, some we avoid, and some we push back against. Then there are the things, institutional forces and global circumstances, like ubiquitous chemical contamination or income inequality, that cannot be welcomed, evaded, or fought against as individuals, but merely resigned to as realities. You’re Hosed is a new, occasional series of interviews with experts about those things.

The corporate cover-up of chemical pollution at DuPont Chemical’s Washington Works plant near Parkersburg, West Virginia, and the resulting class-action lawsuit, have recently been the subject of articles in the New York Times Magazine, The Intercept, HuffPost Highline. The lawsuit uncovered a trail of evidence from as early as 1961 that showed a probable link between exposure to perfluorooctanoic acid, better known as C8, and kidney cancer, testicular cancer, ulcerative colitis, thyroid disease, high cholesterol, and pregnancy-induced hypertension.

While DuPont agreed to voluntarily phase out C8 by last year, it has been a component of Teflon non-stick cookware and other plastic products since the early nineteen forties. Author Callie Lyons, whose book Stain-Resistant, Nonstick, Waterproof and Lethal: The Hidden Dangers of C8, tracks the history of the chemical, is a journalist in the Mid-Ohio Valley who has documented the C8 controversy from the beginning. I spoke with her over the phone to talk about the scope of C8 pollution, its ubiquity in the general population, and what, if anything, individuals can do about their exposure.

How much Teflon is out there?

It’s really hard to find decent kitchenware that isn’t somehow impacted with Teflon. Almost everything we use in the kitchen these days has got some kind of a coating on it, even if it’s not cookware. We don’t realize, it literally is everywhere; it’s everywhere in our household products. So, you know Teflon just in itself is a big deal, but these chemicals that are dangerous and even lethal are used to make hundreds of compounds like Teflon, resulting in thousands of consumer applications.

So would any Teflon product have the potential to put C8 into your body?

If it was made before this year, it does. This is the first year that the companies globally that use C8 and perfluorinated chemicals have promised the EPA to voluntarily not use it anymore. So up until that, that was not, the compromise wasn’t in place before, you know last year was the goal date for it. So reasonably we can’t expect that anything made before that, you know, wasn’t somehow impacted.

So what you’re saying basically is that if you use most kitchen supplies made between the invention of Teflon in 1951 and 2015, you’re at a risk of consuming C8?

Oh yes, absolutely, especially if you’re cooking with them.

So would you say that everyone has these chemicals in their bodies at this point?

Oh yeah, everybody does. The National Institutes of Health can’t find somebody to test that doesn’t. You just can’t find a person that doesn’t already have C8 in their blood at this point in time. And it’s not just from our direct use, but also, it crosses the placenta, so a mother will pass it on to her unborn child. In fact, it magnifies — there’s a biomagnification there so that the child actually ends up with more than the mother has. The mother’s level will be lower than the baby’s level, and around here, that’s pretty scary, because our moms have got some of the highest levels in the world.

And where are you talking from right now, Ohio?

I live right on the West Virginia-Ohio Border. I can literally walk out on my back porch and almost be able to see DuPont. It’s not far at all. So some plants are far-flung from towns — maybe ten or fifteen miles out or something like that — but residential areas go right up to the plant on all sides. So people are living in there, breathing it — I mean we believe the major contributor is our drinking water, but you can’t deny that it’s also been in the air, the soil and the rain. It’s contaminated our whole environment.

Once it’s in your body, is it in there permanently? Can you get it out?

Well, you can, it just would take a long time of non-exposure, I mean on the order of years. So we are continually being exposed where I live here in the mid-Ohio valley. Our levels are going down but very slowly. So the problem here, the quandary is: How are you to not be exposed? I mean that’s a very difficult question. I don’t usually look at the data on my consumer products, but if I were to pop a bag of microwave popcorn right now, even smelling that could give me a big old dose of C8.

Wow, even smelling it?

Yeah, you know how familiar that smell is — there’s nothing like that warm wonderful smell of hot microwave popcorn — but the stuff that is in the lining of the bag, it is very similar to Teflon. So it’s not stable enough to not leak into your food. The government’s known for some time now that you can get a measurable quantity of C8 in your blood, just based on the number of bags of microwave popcorn you eat.

That means that in order to effectively avoid exposure you would have to be checking your consumer products to see if anything in their process used perfluorinated chemicals?

Oh yeah, which would be a daunting if not almost impossible job. But also then you wanna know what your personal environment is: Is there a plant next to you that maybe does something related to these perfluorinated chemicals? People are still finding out all the time that it’s in the water supply and they have no idea. So part of it is being aware of the kind of manufacturing plants that you’re living near, so that you already know what you’re breathing and drinking.

Because you live so close to the plant, people in your area are much more likely to know about C8. But is it fair to say that many more people have been exposed who do not know and perhaps never will?

Oh yes, that’s exactly right. It’s an unregulated substance. If we wouldn’t have had a particular set of circumstances that came about here, with the Tennants’ cattle farm and them finding a brilliant attorney, if the series of events hadn’t happened exactly like it did, we might still not know that this unregulated, odorless, tasteless chemical has been poisoning our water for fifty years.

So you’ve focused your work specifically on C8 and Teflon and DuPont, but this is just one chemical and one company in a whole movement of industry that’s doing a lot of things like this.

Oh yeah, and where I live, we are in a virtual toxic soup of contaminants. Where we live along the West Virginia-Ohio border, it’s just a heavily industrialized area because of access to the river and also inexpensive labor. So DuPont, for this one chemical, C8, it’s just one of hundreds of chemicals from one plant. I don’t think anybody knows the cumulative damage from all of the plants. I hope somebody is keeping track but I have no evidence to show that that would be true. My kids are growing up being exposed to neurotoxins because we’ve got manganese in the air; we know we have really unhealthy chemicals that cause respiratory and breathing problems at a number of different plants here; and then the C8 issue, that’s just a whole separate drinking water issue for us. It’s coming at our kids from all directions.

Generationally, especially with the bioaccumulative effects, it seems as if without our knowing it, having chemicals in our blood and in our water and in the air has become sort of a new normal.

Well, I hope not. That version of the future really scares me. I hope that we can get a handle on this and start to turn it around for future generations. We’re not going about it in the right way. I think this year we can see in particular where the hopeless failure of the EPA is because they’re actually polluters now.

The Washington Works class-action suit can be loosely categorized as a win. But one lawsuit isn’t going to fix the C8 contamination, so even if a community can stand up for itself and win a lawsuit, how much do they really gain?

From what I’ve been told by experts, it will be in our local environment for two thousand years after we stop using it. But a big part of this is medical monitoring. I’m not sure how familiar you are with the class-action but DuPont has set aside $235 million for medical monitoring so that the residents here can have free screenings to determine if they have any of these conditions that have been linked conclusively to C8. So far nobody is using that program. I mean, $235 million set aside for this, and our population is woefully unaware that they can even avail themselves of this.

But also, let’s say that you’re one of the ones who get sick, like [kidney cancer-survivor] Carla Bartlett, who was the first test case — as you probably know, the jury gave her an award of $1.6 million. Attorney’s fees on this are very close to fifty percent; basically most of the attorneys go with a forty percent agreement plus cost, and I’m sure you know these can be very, very costly cases. She was awarded $1.6 million — she’s lucky to walk away with $800,000. Is that worth kidney cancer? No, I’m not sure that would repay for kidney cancer.

It seems like it’s very difficult for the victims of an environmental catastrophe to get what they’re owed.

Absolutely. Really what they’re entitled to would be clean water, a cleaned up environment. But our environment has been damaged beyond repair. There’s the issue of taking care of people who are sick, but there’s also the issue of everyone here deserves a better quality of life than this.

Even if we were able to stop polluting now, the chemicals will be out there in some form for at least two thousand years. Is there much that can be done to remedy the exposure that has already occurred on such a large scale?

There’s really not much else besides the water filtration. That’s the only thing that’s keeping our water from being polluted still, these state-of-the-art water filtration plants. So there is a temporary remedy for that. It’s not the same as having a clean water supply. I guess we’ll have to see if DuPont is going to go ahead and continue to fund those filtration systems. Some people are concerned about the future maintenance, because it’s very very expensive to change out the carbon as frequently as it needs to be.

The sad thing about medical monitoring is that it ends with diagnosis. I know that everyone’s supposed to have Obamacare, or some kind of insurance, but here in Appalachia, we have the most Obamacare-resistant population, probably of anywhere. People do not doctor, they do not have insurance — and for many, many, many people, a diagnosis of kidney cancer would be a death sentence. They have no means of fighting it, so on the one hand, you wonder, Are they better off to know? That’s one of the things I really am concerned with medical monitoring, that it ends with diagnosis. You’ve gotta survive your disease long enough to sue DuPont if you’re going to recover personal injury claim money against your disease.

There’s a lot of loyalty to the company here, a lot. There are people who would rather just die than find out that DuPont made them sick.

Most people already have Teflon in their homes or have had contact with other products containing C8. What are the possible health effects of smaller concentrations of C8 on the general population?

The most recent research suggests that C8 is harmful at much lower concentrations than we are impacted with here. Concentrations that actually could be seen in the public in a lot of different populations, and that’s pretty disturbing, because we’d like to have this be very neat and scientific like, “How many cigarettes does it take to kill you?”

But everybody’s different, so we have these highly vulnerable populations who just the slightest amount of this chemical is gonna mess with them chemically, their endocrinological systems in a way that they have no tolerance for. But at the same we have plant workers, they have exposures thousands and thousands of times higher and sometimes never see an ill effect.

I read that DuPont is phasing out C8 from their commercial products by 2015, but they’re replacing it with other chemicals with a very similar structure to it. How do we know that these chemicals are safe?

Well I think we’re gonna have to always be very vigilant, and one example of this would be that we don’t have toxicology reports yet for the C8 replacements, so how do we know that we’re not moving to something that’s worse? So far DuPont has not been willing to share the toxicology information.

Is it possible to give up everything we’ve gotten through chemicals?

I’m a single mom of two kids, I need every bit of Teflon I can get in my life. Anything that makes our life easier we’re like, “Oh yes, I need that!” and we don’t think about the consequences. So it’s hard to say if it will actually be able to turn around. My only hope for it turning around is that there are some very bright young people coming up that can try to come up with the answers to these problems, and I think it will take a whole new generation with a whole different approach.

This interview has been edited and condensed for length and clarity.

Drake's Playground

by Laur M. Jackson

Somewhere between Azealia Banks’ unfiltered stream of broken-clock consciousness and Sean Carter’s online (almost) non-presence lies an entire industry of musical artists who engage with social media with all the colorful distinction of eggshell white. Sure, interspersed between musical promotions and product announcements, many artists tweet and ‘gram with a casualness that suggests a unique voice or persona. But to compare and contrast the online presence of say, Ariana Grande and Gwen Stefani, as cultivated by the artists themselves, even the truest stans might have difficulty differentiating them on any sort of non-convoluted terms. The hashtags are too on point, the display just too prettily arranged, such that even the touches of internet vernacular — superfluous exclamations, a reckless lowercase — cannot prevent celebrity accounts from appearing exactly as the analytics-driven, corporate-approved productions that they are.

But then there are the artists whose online voices are so particular as to be almost an extension of their own creative work. Nowhere is this more readily observed than in hip hop culture. The prevalence of social media in hip hop is hardly surprising — as a culture driven most potently by creators’ abilities to invent a visual and vocal trademark, a style and presence all one’s own, the opportunity to expand into the virtual realm just makes sense. In rap, as one expansive genre within, this presence is substantiated by the individuated personal pronoun “I.” The “I” is an anchor, a liberating one, that allows variation and experimentation while maintaining the brand identity of a still-recognizable artist. The “I” of rap, Katja Lee explains, is made of “both reality and myth,” inclusive of the rapper’s own multiple voices (Busta, Kendrick) and multiple personalities (Eminem, Nicki) retained within the singularity. Slim Shady is still Eminem, but also Eminem is Eminem and Marshall Mathers; Nicki Minaj is Roman is Barbie is Martha is Nicki is Onika. Though arguable, a rapper’s ability to develop a recognizable and authoritative vocal persona may even supercede lyrical expertise in delineating the Greats from the “who is this?”-es.

The internet demands inclusion as a way to distinguish individuals in our contemporary rapper genealogy for this reason. “Old school” and “new school” as style categories are generally limited to evaluations of whether a rapper represents a resurrected likeness of the Greats of old (or not) — contemporary rappers who “take us back” and inhabit a “classic” sound versus those whose artistic commitments lie elsewhere (for better or worse, depending on who you ask). But old school / new school acquires better coherence for consideration of how new(er) artists utilize the internet (or don’t) to constitute their voice.

Though perhaps not in terms of monetized spread, the new school reigns online, headed by rappers whose style can best be described as internet-extraordinaire: Tyler, The Creator; Childish Gambino; and others for whom persona seems as influenced by the internet as the other way around. Those two especially have, it seems, built their millennial-heavy following through their adroit manipulation and exploitation of internet culture.

If asked to describe Gambino, Tyler, Earl Sweatshirt, or Lil B to someone who had no clue who they were, my guess is that most would begin, justifiably, with their various internet-related antics: from Lil B’s curse to Tyler’s early penchant for all caps, to Gambino’s most successful album to date, Because the Internet — which, despite numerous listens, I can’t seem to describe in any way but “internet sublime.” But even as these artists are in fact incredibly invested in internet culture, they have a nonchalance about their craft that feels just as much so us as the ability to flawlessly incorporate meme’d lingo in their lyrics. Gambino allegedly selected his name from a Wu-Tag Clan name generator — exactly the bittersweet mixture of nostalgia and irreverence — and Pitchfork’s Mike Powell’s assertion of Lil B’s disinterest in anything like an artistic legacy might be correct.

A photo posted by Nicki Minaj (@nickiminaj) on Dec 24, 2014 at 4:39pm PST

In some ways the ascendant, afro-futurist final evolution of internet weirdos Gambino and Tyler (who are moreso overwhelmingly afro-present), Nicki Minaj absolutely revels in all things social media. A culture of memes, clapbacks, emojis, photo responses, selfies, screenshots, and shitpics are all raw material to be reposted, repurposed in the sonic particularity of her persona. In effect, social media temporality only intensifies Minaj’s own instantaneity, as a rapper with an affinity for shock and disturbance who punctuates her work with all manner of growls, pitch changes, chuckles, tongue rolls, and others sounds that defy my descriptive capabilities.

Stan that I am, I ever remain in a follow/unfollow relationship with Nicki’s Twitter account, annoyed by the borderline breaches of netiquette, the flood of replies offset for all to see, yet amused in spite of it all. Finding out Nicki has a ghost tweeter would be more devastating than Drake’s ghostwriter revelations because her online persona seems to be a 1:1 match for what she puts out there as a performer. Follow Minaj, and she holds court on your timeline; follow Minaj and never question the glorious, flawless, monstrosity of her rapperdom.

By comparison, someone like Drake, despite his occasional playfulness on social media, has often seemed earnest, almost to the point of vintage. He’s a rather odd fit in the old school/new school matrix of contemporary rap. He has the resume to fulfill the quirky, hipster-ish type: His core fan demographic (people my age?) remember him well on Degrassi. Though Drake doesn’t hide from Jimmy, he also hasn’t really parlayed that role into any sort of guaranteed millennial-cosign via nineties-kid nostalgia. His lyrics display a fondness for analogies legible to we raised on the Frat Pack (“race for your love, shake and bake, Ricky Bobby”) and Pixar (“swimmin’ in the money come and find me: Nemo”), but he is no Gambino, whose flow literally thrives on punning (look no further than “Sweatpants”). Gambino disowned his 2005 The Younger I Get in part because of criticism that it was “an overly-vulnerable Drake-lite,” as if too much raw investment, is, in his metric, indeed a bad thing. If Gambino is the irreverent internet mad scientist, Drake is the very serious scholar: the hip hop historian.

In a mixture of appeals to an established industry apparatus and flippancy about rap’s conventions, Drake released a mixtape on iTunes and charged for it. And yet, he also uploads tracks to Soundcloud, an indie-ish venue shared by artists of local celebrity and oh-god-no-why amateurs alike. In the currency of track features, Drake distributes his voice widely, but has never appeared super hungry for guest spots from established giants to validate his own work in exchange — a youthful arrogance much akin to another peer, Kendrick Lamar. His rise, however, is quite old school: introduction via an uber popular mentor — Lil Wayne — within a crew of similarly positioned apprentices, a loyalty to whom he maintains, irrespective of success.

Part of Drake’s mixed musical heritage includes an openness to pop’s conventions to validate himself as an artist within hip hop. Though Beyoncé is not a rapper, Drake has, it seems, learned much from her — how an acquired prestige allows for a certain abstraction on social media, even the withholding of one’s own vocal signature. Especially in this most recent era, Bey is every bit the visual artist, whose voluminous vocals are reserved for the stage and track alone. Even her Tumblr, substantiated by an “I Am” reminiscent of a lyrical speaker, is an image-first enterprise. Her “seen, not heard,” “art first” campaign remains topical since that world-stopping album release, reignited with her appearance in the prestigious September issue of Vogue sans interview, quip, or signature. Anyone in the BeyHive can point out her preference for handwritten messages — some even saw her typed out congratulations to the recently wedded Kim and Kanye as a snub — as if even her text must prioritize a visual eminence. The intrigue is masterful and something only an artist at her level could achieve — as Yale professor Daphne A. Brooks describes, an at-once “hyper-visibility and inaccessibility,” cultivated in the past by others like Josephine Baker but overall not a privilege generally available to Black women, celebrity or not.

Leon Neyfakh, in as comprehensive a character study can be found of Drake, observed in his performance at this year’s OVO Fest the final notch in an ascension from hip hop personality to virtuosic pop god — on par with Kanye, Swift, and of course the Queen B herself. Much like the Queen, Drake has an uncanny affinity for anticipating the activity of his audience, providing what we want most to latch onto before even thinking to ask. Neyfakh likens Drake’s attunement to superpowers, to which I’ll add another — a trending clairvoyance, if you will. Beyoncé launched “to the left,” “put a ring on it,” and “flawless” (honorable mention: “surfboardt” and its various derivations). Drake gave us the Motto — YOLO — but that was only the beginning.

Insanul Ahmed wrote last year that Complex has long speculated that Drake “wrote all his lyrics with social media in mind.” Even those deterred by certain lyrical red herrings as recent as “Energy” (“Fuck goin’ online, that ain’t part of my day” is an easy catch, but how mocking are those stretched vowels on “Wi-Fi,” “timeline,” and “friends”?) must now disabuse themselves the pre-beef notion that Drake is anything but the ultimate hip-hop technocrat, the anti-managerial flipside to Jay-Z’s practiced stewardship. He is the foil. Hip hop’s Night’s King. In Drake’s case, the “I” online was very very silent and we were never so ripe for manipulation as when we mistook that silence for absence, though anyone who’s been paying attention long realized he has been among us all along.

As relayed by — yes — Meek Mill, “This social media world was,” according to Jay-Z, “created for people that wouldn’t even speak if they wasn’t present.” The “they” here is ambiguous. It is unclear whether, as translated by Meek, it is an accusation of cowardice or voicelessness, bravado or non-persona. AAVE allows us the slippage. The former — “if [social media] wasn’t present” — implies a demographic emboldened to the point of disrespect. Those who are truly, in the words of Hov, “loud as a motorbike / But wouldn’t bust a grape in a fruit fight.” Irony not lost that the message resonates with Meek. But the latter insertion — “if [people] wasn’t present” — somehow is more characteristic of a rapper of some sort of old(er) school, potentially past his lyrical prime, yet as virtuosic in voice and character as ever.

I’ve seen it said more than once that nobody can clown Drake more than Drake himself, which remains ever true. He takes in memes, mediates them in lyrics, and produces a new meme regime. Out of Drake’s rumored preference for bigger women (from partners who aren’t quite as reserved on social media) and jokes at his expense, the rapper made “the type to want to suck you dry and eat some lunch with you” a repeatable category, with a knowing nod to the phraseology of the many “Drake the type” memes out there. Out of his Canadian roots came 6God. To claims that his softness (by virtue of a supposed deviation from black heteromasculinity) makes him rapper-ineligible, he put out “Started From the Bottom” and had a whole nation of white kids pasting the lyrics on #TBT uploads, yearbooks, and graduation photos. His latest solo-mixtape-slash-album-or-who-knows-what-to-call-it, released the Beyoncé way, features album art with the punctuation removed — as my colleague Jean Thomas Tremblay observed, If Youre Reading This Its Too Late is preemptively hashtaggable, trendable, thus begging to be circulated. The font is easily replicable: Less than 24 hours post-release, designers Rik Lomas and Simon Whybray put up a site allowing users to create their own IYRTITL parodies.

From YOLO to “woes” Drake has understood his position as a persona readily meme’d, gif’d, and packaged for circulation on the internet. The adaptive quality of his image knows itself as ripe for rumor and memeification. He is, arguably, the most memeable rapper of all time.

(Soon to be supplanted by DJ Khaled? The differences between Drake’s and DJ Khaled’s memeability is certainly worth thinking about. Both are certainly interested in monetizing memes in some way, though Drake seems to be reaching more towards a cultural omnipotence undergirded by assets, while DJ Khaled is more content to sell gear and (maybe?) endorsement deals — Dove and Listerine as the key to success? But also people are already starting to get burned out; bound to happen to a character that deals in stock phrases versus adaptivity 🔑)

Drake, too, is very much art first in voice, yet remains tuned in enough to transcend the internet as an entity that always seems to be accumulating the means to make him a mockery. How much Drake actually enjoys the internet was an undecided question when I first set to write on this subject early summer, long before Meek’s mouthiness forced the technophobic facade to drop, before our first undeniable instance of Drake interacting with the internet on a memeified level. Since then, the proverbial curtain pulled aside, we now get to see a Drake totally involved in internet play. And it’s great! He posts memes! Like, often. Shitpics, too! Screenshots! And whatever we call those photos where you use a still image or gif to illustrate affect.

Nothing yet indexes Drake’s transition better than the release of and subsequent mania over the music video for “Hotline Bling” (which refuses to die). The video’s choreographer Tanisha Scott — a very Drake choice in vein with the rapper as historian, which says “I’ve done my homework” — describes Drake as “borderline brilliant,” a genius the fellow Toronto native anchors to his (meme instincts). “We were looking at playbacks, and he was like, ‘This is totally going to be a meme.’” And it totally did.

A photo posted by champagnepapi (@champagnepapi) on Dec 18, 2015 at 8:20am PST

Another Toronto institution almost in his own right (if the ability to siphon Drake’s language through a dad-like, politics-obscuring charm counts), city councillor Norm Kelly has been enfolded into Drake’s world for real, a development that feels more a part of the fun of shared nativity and ascendency than some sort of career maneuver on behalf of either. This is where I bow to Toronto writer Amani’s expertise on Drake as an artist whose creative attunement is irrevocably substantiated by his Torontoness / Blackness in ways often overlooked or clumsily excused by critics. To avoid doing the former at least, I’ll note that an acuity of the networks that constitute Aubrey Graham’s diasporic hybridity must be woven into any forward-thinking analysis of Drake-the-rapper.

So there is of course a risky flipside to all this fun. My mom uses “oversaturated” to describe celebrities whose everywhereness has overstepped the bounds of relevance into the realm of nuance. Oprah, Beyoncé, and more recently Justin Bieber and Taylor Swift have all — for her — fallen prey to a presence that doth protest too much, that tries too hard — that, in other words, reveals a little too much the churning involved on behalf of a superstardom’s corporatized underbelly. (Think she’s coming around on Bey, though, through no small effort of my own.) Even well-orchestrated memes depend on at least the illusion of spontaneity. Someone has to be the loser, caught off guard and unawares. Where “too good” actually becomes a liability, overexposure to Drake’s meme genius could see him divested of trickster status for real. From jokester to clown.

I am wary, but trusting. To say Drake takes himself less seriously or to call this relax-mode would be foolish. For it is in fact this most recent levelling up that allows room for a revelry not previously made visible. Maybe Drake is a pop superhuman — only, what other genre but rap is expert signifyin’ the ultimate power move? Even a casual Bergsonian reading of the comic knows the very event of humor involves the equivocal superpositioning of parties involved, with Drake as one constellary persona in a solar arena of performers needing to eclipse each other by any means necessary.

The counter-intuitive bottom line is that he has passed a threshold of his own making and can now truly embed himself in the internet low: Be one of us, reachable by virtue of untouchability. No longer the panopticon — yet as panoptic as ever — this emergent-era Drake knows his always ever-eminent triumph on the internet and as such, transforms what that space means for him as an artist and for us as an audience. Not an arena or even a stage any longer, the internet is his playground and we’re all invited.

David Bowie, "I Took a Trip On a Gemini Spaceship"

This cover of a song by nominal inspiration The Legendary Stardust Cowboy — itself an homage to the Jimmy Van Heusen/Johnny Mercer standard “I Thought About You” — may be my favorite late-period Bowie track. We’ll move on soon enough, but today there’s this.

New York City, January 10, 2016

★★★★★ The darkness and the sound of heavy rain kept a long deep sleep in place, till the late morning brightened. The view out the rain-spotted glass darkened again, then the light swelled again. The clouds blew quickly northward, tearing as they went, revealing white and blue beyond them. A window or two had been tipped open on the glass tower across the street. It was mild enough to try sliding the living room window open; the air came in fresh. The sky cleared further, and suddenly a blinding gold-white fog filled the view to the south. As the swimming things were being gathered for a trip to the pool, dark gray closed overhead again. The sidewalks by the avenue were mirrors and a light rain was pattering down, even as a jaundiced light overspread everything. The four-year-old trudged along uncomplainingly with raindrops landing on his raised hood. All at once a full rainbow was crossing the air over Broadway, spanning the whole northern sky. There was nothing elusive about it; everything changeable and erratic in the heavens had rendered a firm and logical conclusion. It held there for minutes, a feature of the landscape, revealed from different vantage points as one walked: passing behind buildings at its high point, plunging down over 72nd Street and east toward the Park, where it lingered after the left-hand part had faded. The boy’s socks were wet. Rugged majesties of gray and pink moved through the sky out the wall of windows by the pool. A bit of delicate pale blue glimmered on a knot of cloud high up in the gathering dark. It was not cold yet on the walk back, but the wind was gathering force. By bedtime it thumped against the building.

The Selling of Ancient Egypt

by Rachel P. Kreiter

Buried within Ancient Egypt Transformed: The Middle Kingdom, an exhibition at the Metropolitan Museum of Art dedicated to artwork from the four-hundred-year period of Egyptian history between roughly 2000 and 1600 BCE, is a squat sky-blue hippo figurine whose body is inscribed with lilies. This is William the Hippo. William is made of faience, a self-glazing ceramic-like compound out of which the ancient Egyptians crafted beads, dishes, amulets, inlays, and goblets throughout their history, from about 3000 to 30 BCE. This figurine is arguably the best-known piece of faience in the world, if not the best-known piece of Egyptian art.

William encapsulates ancient Egyptian beliefs as well as the essence of Egypt’s brand appeal: He’s the Met’s “mascot,” marketed to children since at least 1936. You can buy him as an eraser, a reproduction, a stuffed animal, a magnet, or a pair of earbuds. With such a commercial presence you’d think the actual show would flog William for all he’s worth, which I daresay is a lot if they’re still making staplers out of him. Yet if you look for William in Ancient Egypt Transformed you’ll probably never find him, the poor thing: He’s stuffed into a case with several other faience hippos. Go ahead, look for him. I’ll wait.

William’s limbs are reconstructions. The color is a subtle mismatch, with discordant finishes — the legs matte to the torso’s glossiness. One surviving leg provides another obvious contrast, with articulated toe joints absent on the reconstruction. Before he was placed in the tomb of Senbi around 1900 BCE, William’s legs were broken. It was ritualistic, Egyptologists think — hippos were dangerous in Egypt, a chaotic disruptor to life on the Nile. Putting a hippo in the tomb was apotropaic, but to disarm his destructive potential toward the tomb owner, William had to be physically rendered harmless. That William’s legs are purposefully broken is evidence that the Egyptians performed the act of neutralizing chaos, ensuring that life will continue, even in death.

To exclude William’s nickname from the label, to bury him so deeply within this exhibition, is testament to a few truths about Ancient Egypt Transformed which could stand as a whole for truths about how Egyptologists deal with, and how the general public sees, ancient Egypt. To exclude the reputation — the legacy — of William the Hippo from an exhibition about the visual material of the Middle Kingdom is to deny a truth about Egyptian art itself: It’s as much a scholarly artifact as it is a cultural product. The curatorial choices evidence a masterful understanding of the history of ancient Egypt and its culture; Ancient Egypt Transformed is comprehensive to a fault, even devoting a section of the show to the museum’s extensive, century-long archaeological mission in Egypt with a to-scale model of a Middle Kingdom pyramid enclosure. The exhibition’s marketing, branding, and educational initiatives function as a separate entity, driving home how valuable a commercial property ancient Egypt can be. What’s weird is how these two seemingly disparate programs alternately push apart and work together within the show.

A couple of days after I saw Ancient Egypt Transformed, I found myself in the Gagosian on 21st Street, in white rooms with tall ceilings looking at Jeff Koons’ Gazing Ball Paintings. These are reproductions of painting’s greatest hits from the art historical canon, each with the addition of a blue gazing ball that sticks out from the canvas. At best — most charitably — the coherence of the full body of work, the collection of eras in a single space, all with a blue ball added, is the thing that made that installation successful; each room was an exercise in overwhelming the audience with the familiar. Perhaps there’s an intellectual conceit in forcing the viewer to see their reflection in the ball within these paintings, or perhaps a creative validity in the uniformity of the reproductions, which hung without frames, each roughly (though not exactly) the same size, the same dimensions. Such varied art, so many contexts — El Greco, The Raft of the Medusa, that kind of thing — and all of them stripped away.

I bring this up not because I want to talk about that show in particular, but rather, to get at the fallacy in declaring that something isn’t actually art. The only conversation you can really have about Jeff Koons is whether his work is good or not — but what he does is undeniably art. Over dinner a few hours later, the conversation turned to 3D-printed rocks installed in a park, which my friend dismissed as “not art.” You don’t have to like the rocks or the gazing ball reproductions, or really anything, but you can’t deny their transformative character — which conceptually, and legally, makes them “art.” Maybe it’s art if you’re sitting there discussing it; maybe that should be the measure. Instead of whether or not it is, the best argument to have about art, assuming you already know what it ‘means,’ is whether or not it’s good.

A major complication in the museum display of ancient Egyptian art — any ancient art — is that good or bad is beside the point. Egyptologists are not sure if the ancient Egyptians made art at all. They had no word for it, only a term more closely akin to our definition of “craft.” The objects we call “Egyptian art” were produced by a culture whose goal in making beautiful things was so fundamentally different than ours that to review it as if the art is good or bad — as New York Times art critic Holland Cotter did upon the show’s opening, even as he noted the lack of an Egyptian term for “art” — doesn’t serve the purpose of creating meaning for the artwork itself.

Some Egyptian objects seem more carefully carved, are better articulated, or more richly detailed than others. Yet careful or detailed work doesn’t equate to “good” in modern Western practice by any means. Robert Rauschenberg’s white monochromes aren’t detailed in the slightest; closer to Egypt, Matthew Barney’s Djed installations are basically piles of melted garbage, neither careful nor attractive. These are things that are broadly considered “good,” though not everyone would agree. What makes them successful as artworks has nothing to do with whether they look appealing and everything to do with context: the times and places in which they were made, the historical works they draw upon, the works they would later inspire.

How do you display Egyptian art if you can’t quite, and perhaps shouldn’t, judge its quality on a twenty-first-century metric? Here’s a bridge between ancient and contemporary art: ancient art can also be evaluated by the time and place of its making, historical antecedents, and artistic successors. This first criteria can be filled in, broadly, like this: The point of making these things in Egypt, beside resource control and status signification, was to mimic the act of creation, to shape raw matter into purpose and meaning, to cause something to appear from nothing, as if by the same magic that created the world. The quality of the artwork doesn’t negate the transformative process inherent in making Egyptian art.

The traditional view of Egyptian history dictates that three major epochs of united, stable government under a single ruler, called kingdoms, were each disrupted by “intermediate periods” when the country became fragmented and, concurrently, the quality of the art declined. This is a modern construction in the strictest sense of that concept. Though by Greco-Roman times a priest named Manetho had recorded a division of Egyptian history into dynasties, surely no one woke up the day Nebhepetre Mentuhotep took the throne and determined that art could be good again. Ancient Egypt Transformed concerns material produced at that juncture and up until the political stability of Egypt collapsed again to usher in what we call the Second Intermediate Period.

If a major art museum is going to mount the very first exhibition dedicated to masterworks of the Middle Kingdom of ancient Egypt, there’d better be a unifying principle through which visitors can come to understand what makes this period more unique or special than what’s on display literally downstairs in the Met’s permanent Egyptian galleries. That principle is there in the exhibition’s title participle. Arguably, it’s the transformative character of the work that justifies such a large exhibition dedicated to a single period. With the surety of hindsight, this exhibition argues that the Middle Kingdom was when the Egyptians stopped fucking around and started making art. Middle Kingdom work is skilled and accomplished, and the Metropolitan Museum has a major stake in codifying that position. Their first Egyptian excavation concession in 1906, concurrent with the establishment of the Egyptian department, was at the Middle Kingdom site of Lisht, around forty miles south of modern Cairo and the ancient capital of Memphis. The Met continues digging there nearly a century later, despite the fact that the partition system through which the museum was able to easily take home antiquities ended long ago. Before that, though, the museum was able to acquire some fantastic stuff. The ne plus ultra of Middle Kingdom tomb models, for example, is the cache from the tomb of Meketre, now split between Cairo and the Met, which excavated that burial in 1920. Some of those models appear in Ancient Egypt Transformed, as do some relief blocks from the Amenemhet I pyramid complex. In the permanent collection downstairs, these landmark collections are each housed in their own galleries.

The Met’s collection of Egyptian artworks is so huge and so complete that it could claim to have a special relationship with any period. It might as well say it has the American monopoly on complete Roman Nubian temples — it’s true! It’s also true that the Middle Kingdom has defied some of the branding given to the Old and New Kingdoms. In the former you have the “Pyramid age” and in the latter, celebrity royals like Nefertiti and Tutankhamun. Alongside sphinxes and biblical narratives, these are the most visible and exciting aspects of ancient Egypt to modern Western consumers. Presidential candidates wouldn’t be sounding off about these things if they weren’t. (Never mind that the pyramid age proper continued into the Middle Kingdom; these later pyramid complexes are no longer picturesque, long deteriorated. They’re not wonders of the world, exactly.) People will not stop asking me if the Giza pyramids were used to store grain. Meanwhile, the modern Western world wouldn’t keep making (sometimes successful) big-budget screen epics about Egypt if those weren’t, you know, marketable.

Is the Middle Kingdom marketable? The Met is trying to make it so. The exit gift shop, for example, was selling poster collaborations with Banquet Atelier and Workshop, a “Vancouver-based studio engaged in creating quality goods celebrating the natural world and the animals that inhabit it.” My favorite creatures inhabiting the natural world have always been Sobek, the crocodile-headed humanoid god, and Osiris, the former king of Egypt who was hacked up into little pieces and reformed as a mummy to stand or sit, magically bandaged so that his hands just barely clutch a crook and flail, in judgement of the deceased. These deities, and others, appear on a poster that you can buy for seventy bucks. It says, in huge block letters across the bottom, EGYPTOLOGY. Egyptology is fun, but if you are the sort of person who would buy a poster that says EGYPTOLOGY on it, you’re part of the problem. This poster and others were on sale alongside scholarly volumes like Dieter Arnold’s heavy tome The Pyramid Complex of Amenemhet I at Lisht, a substantive resource for Egyptologists, archaeologists, and architectural historians, but which is useless to almost anyone who would go see Ancient Egypt Transformed. The shelf of William merchandise — knick-knacks, note cards — has broader appeal and is priced more reasonably.

It’s not that selling to multiple demographics is in itself a bad thing; the Met is “encyclopedic” in multiple senses. It’s that the catch-all nature of the gift shop begs the question of who is this exhibition is for. Papyrus and sherds, some scrawled in hieratic, the cursive of glyphs, appear throughout the show. The Middle Kingdom was a literary renaissance in ancient Egypt, and these texts are crucial to the aesthetic and cultural character of that period. They don’t look like much, though, and no layperson can read them. Translations are present but the objects themselves take up considerable real estate in the exhibition space. What do these ancient documents have to do with art? It’s a nod to Egyptology, wherein artwork is often no more than a conveyance for, or visual example of, written texts. Within the show, it’s difficult to imagine these objects competing with statue portraits of the king Senwosret III, whose grave, drawn features are shockingly distinct from the typically idealized images of Egyptian kings, or the little tomb model of a cow birthing a calf on loan from the Royal Ontario Museum. For an art museum audience, works like these are far clearer about how transformation played a part in Middle Kingdom aesthetics.

Until recently, an exhibition downstairs called Kongo: Power and Majesty concerned the aftermath of the Portuguese encounter with the Kongo peoples in the fifteenth century, which led to the colonial devastation that attended the trade networks Western culture grew to thrive on, serving up people, sugar, works of art. Like was shown with like in Kongo — power figures called minkisi grouped together, carved elephant tusks called oliphants grouped together, Christian crosses grouped together. Ancient Egypt Transformed, in contrast, begins with any and all objects dealing with the king, then moves on to royal women, elite officials, foreign interconnections, and the afterlife and its practices. Toward the end of the show you’ll run into three different model boats. Initially I felt there was no need for three model boats in a show that feels this packed. Increasingly I can’t help but envision a Middle Kingdom show where there are even more model boats, as many as possible, “good” ones and “bad” ones, in varying sizes, all displayed in a herringbone pattern like the little armies of minkisi in Kongo.

The art of the Middle Kingdom could be distilled into a limited number of defining canonical types of work: the model boats; the rectangular wooden coffins with bands of colorful inscriptions and a pair of painted eyes where the mummy’s head lay so the deceased could look out; the squatting block statues of cloaked elites we sometimes call Würfelhocker; limestone funerary stelae; so-called “magic wands” of ivory incised with bizarre creatures; pristine and precious jewelry. And faience hippos, for sure.

The variation in these corpora is thrilling, and would speak to how within a supposedly uniform culture under an autocratic divine king there are glimpses of humanity in Egyptian art. It’s in looking at these objects together that the show’s raison d’etre would be most undeniably evident. I don’t know if it’s truer to guess that we simply have more surviving Middle Kingdom works than earlier material, or if decorum loosened just enough in this period, but if there is a transformation in Egyptian artwork at this time, maybe it’s the explosion in artistic decision-making that leads to such a wonderfully bizarre body of work. Some of the best objects in the show are those a Romanist might sniff at as “provincial” — an arm too long here and there, reaching uncomfortably across the gap between two bodies or up into the above register on a stela. Without imputing sentiment to long-dead nobodies, it’s possible to drink in the variation in the materials produced by a society in which order, consistency, and stability were religious doctrine. (Or so we think.) The value of Egyptian artwork is in its texture, not the tactile but the conceptual kind, in its many interruptions and deliberate breaks.

Which brings us back to William the Hippo, or rather, William’s broken legs. As I was sifting through the stack of leaflets and papers I brought back from the Met, I picked up the Family Guide: Pharaohs, Sphinxes, and Hippos. William, in line art, is turquoise against a yellow cover. Inside, under a picture of the figurine, the text tells kids about the lotuses on William’s body as symbols of rebirth. “Look closely,” the guide says, “how are these hippos the same or different from each other?” (It would be so satisfying if this question were followed with a second: “What does it mean that the Egyptians made the same thing over and over, each time subtly different?”) The name “William” is never mentioned. There are many surviving faience hippos in this world, and a few in this show. But there’s only one William, and it’s obvious without even mentioning his name that he’s the hippo in question. Given the William merchandise in the gift shop, you could roll your eyes at how the teachable moment of seeing a pod of faience hippos is transformed into native advertising.

The best thing about ancient Egypt is its frustrating existence in two worlds, the academic and the mainstream, which fuel and contradict each other, deny and encourage. The real test of this show will be not how good it was according to critics, but rather, whether something from the Middle Kingdom is able to transcend its scholarly trappings to be sold on a mug.

Photo of William the Hippo by The Met

Time of Your Life

by Nicole Boyce

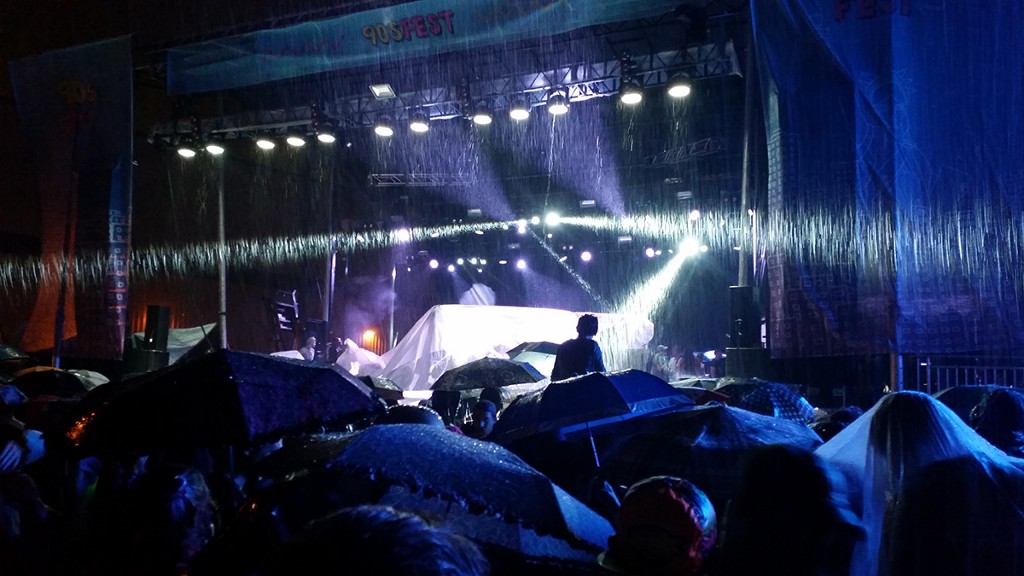

I saw the first denim scrunchie before I’d even reached the venue. A woman in front of me was wearing a Sandlot t-shirt with the caption, “You’re killing me, Smalls!” Another woman, wearing a shirt that just said, “The 90s,” posed a friend for the camera. “You’ve got to move the vest so we can see the t-shirt,” she said. “There ya go.” Her friend’s t-shirt read, “You’re a virgin who can’t drive.”

I’d been thinking recently about the way that nostalgia is now being sold back to millennials — the past marketed and re-experienced for a fee — which is why I was waiting in line on an overcast Saturday morning in Brooklyn for the inaugural 90sFest, a one-day music festival featuring Coolio, Smash Mouth, and Salt-N-Pepa, among others. Organized by promoters Leuven Media, Prime Social Group, and Founders Entertainment, tickets for the festival sold for between $50 and $150. (It was far from the only marketed experience capitalizing on millennial nostalgia this year: Marketing Magazine, Adweek,and Forbes have all run articles on nostalgia marketing in recent months, while Vogue called 2015 “the summer of 90s music”; Marilyn Manson did a summer tour with Billy Corgan; and Sugar Ray recently finished a tour with Eve 6, Better Than Ezra, and Uncle Kracker.) As we approached the festival gates, I peeked inside at the scattering of side ponytails, chokers, and butterfly clips. It was like the blue fairy had waved her wand over a BuzzFeed gallery.

I’d been inside for less than five seconds when someone handed me a promotional bill printed with a Mars Attacks alien, Kevin McCallister, and the logo for SmileTrain, 90sFest’s charity partner. I spotted a cluster of Rugrats mascots and hustled over to get a photo, but couldn’t figure out where on the mascot’s foamy body to put my hand. Did I just accidentally touch its butt? Which part is the butt? The mascots were standing between a Sunny D booth and something called Betches Bedroom, a detailed re-creation of teenage girlhood stocked with Beanie Babies, an *N Sync poster, and Steve Madden memorabilia. A woman in a tattoo choker manned a GIF photobooth inside. “Where can I get one of these?” a visitor asked her, holding up a pillow that said “#Betches Love the 90s.”

“Sorry, we made those special,” the choker-wearing staffer said. Her co-worker joked to me, “Maybe we should sell them.”

“Bet you could make a fortune,” I said.

She laughed, then looked at me earnestly. “We are selling tank tops, though. They’re $44.” She pointed at a grey tank top printed with the words, “Dawson’s Fleek.”

When it comes to re-experiencing our youth, we can’t divorce memory from economics. The Atlantic’s Megan Garber has described the current state of nostalgia as a “memorial-industrial complex. While the word “nostalgia” used to be associated with Madeleine-induced warm and fuzzies, Garber explained, now memory is often experienced as a media product. Our past — thanks to the Internet — is instantly accessible and always available for purchase. As Trent Moore declared in his recent Blastr critique of Hollywood’s Jurassic reflux: “For better or worse, nostalgia is the new currency.” 90sFest, then, isn’t just whimsical marketing: It’s calculated economics. As Bruce Starr of BMF Media Group noted in an interview with BizBash, booking nostalgic acts is extremely cost-effective, since the hit-makers of yesteryear typically bill less than artists with current no. 1 singles, all while tapping into built-in fan-bases and publicity potential. For attendees, throwback festivals are a chance to reminiscence, and an excuse to revisit acid-washed jeans. The experience isn’t just about the music, but about the overalls andfloral dresses that are enjoying their comeback heyday. Blogger Vladimir Vukicevic has theorized an S curve for nostalgic appreciation that’s visible in the fashion industry: Pop cultural items move from an establishing event and gradual appreciation period to a nostalgic apex — usually twenty years after the fact — then depreciate as nostalgic capital. If fashion is a Venn diagram, nostalgia is the spot where hipster and Hanson overlap, and 90sFest is a hyper-concentrated version of that performative nod backwards.

“My name is Pauly Shore,” our host announced as he took the stage shortly after 2pm. He looked tired but self-amused in a loud printed t-shirt and shorts set, his Son in Law hair long since cropped off. He began hyping up the crowd, gesticulating with a bottle of Sunny D. “How many Lisa Loeb fans are here?” he asked. A big cheer. “What Lisa Loeb songs can you name?” The crowd went quiet. “You don’t like Lisa Loeb,” he sneered, then started listing his movies — Biodome, Jury Duty, and Encino Man — which elicited another huge cheer. “Those are all movies from the nineties,” he said, squinting out into the crowd. “They asked me to host because that’s when I was really popular.” The crowd laughed, then got quiet again, unsure of whether we were supposed to laugh. “At least I’m still fucking alive, right?”

“Everybody (Backstreet’s Back)” played on the speakers and Pauly gyrated in his Hawaiian outfit, shouting at people to dance. “You guys, this was life before the fucking internet!” After what felt like many minutes, he left the stage and the band Tonic stepped on, launching straight into “Open Up Your Eyes,” a crowd-pleaser. I was struck by how many Tonic songs I know — “You Wanted More,” “Sugar” — and by how tight the band’s performance was, delivering well-harmonized vocals and spot-on instrumentals. If Tonic is washed up, they’ve washed up wholly intact. It occurred to me then that 90sFest was not just a fashion show or an orgy of elastic cuffs and orange drink: Tonic is a seasoned band who plays well-loved numbers, and for them, 90sFest wasn’t a novelty act, it was a music festival. After indulging us with a group sing-along to “If You Could Only See,” the band left the stage and the festival’s kitsch flowed back in full force. A man dressed like The Mask strutted past the Sunny D booth, a woman wore a Spice Girls collectable sticker on her bicep, and another woman, in pastel cargo pants, flirted with a man in a vintage t-shirt. I hadn’t seen anyone flirt in cargo pants in a long time.

Over the course of the day, I talked to a number of festivalgoers. Katie, twenty-eight, wore overalls and a backwards baseball cap, while Ashley, thirty, had a row of butterfly clips in her hair. They both live in New York, and found out about the festival through a Facebook ad.

“Is there a band you’re especially excited to see?” I asked.

They shook their heads. “None of the performers are my favorite nineties performers,” said Katie. “But I know a handful of songs from each, so I thought, ‘It’ll be awesome.’”

I knew what she meant. I too have fond, if vague, recollections of most of the performers, but I don’t own an album by any of them. I asked about the outfits. Ashley bought her butterfly clips from a stand in the festival’s marketplace, while Katie’s overalls came from an H & M. She mentioned something that came up with every person I talked to — how difficult it was to tell en route who was dressed up in nineties garb for the festival and who was just from Brooklyn.

I asked Katie about her shoes — Vans with hearts doodled on the side — “That’s how you can tell they’re from ten years ago,” she said. “I haven’t drawn on my shoes in ten years.”

Next, I talked to Olivia, twenty-five, and Sanders, twenty-four. Olivia said the outfits were the biggest reason she wanted to attend the festival. “I actually bought this whole thing,” she said, pointing at her backwards hat, overalls, and leggings. “I went to both Goodwill and Spencer’s yesterday, I’m ashamed to admit.” She did a lot of internet research to curate the look. “This is mostly based on Clarissa Explains It All.”

“Where did you get your fanny pack?” I asked Sanders.

“Some friends gave it to me in college,” he said. “It’s actually a JammyPack.”

That sounded to me like a cartoon onesie gang, but Sanders demonstrated that the pack housed a mobile speaker system. This was 2009 dressed up like 1993, resurrected in 2015. Nineties culture, over time, has been essentialized into a few symbols: phat pants, Doc Martens, mini buns.

Around 3:30pm, Coolio took the stage in a hat customized for his braided pigtails. Midway through his performance, a recording of gunshots played, and Coolio left the stage. He returned, wearing neon orange Wayfarers and a Notorious B.I.G. t-shirt, then launched into “Gangsta’s Paradise.” Ecstatic howls rang out through the crowd. Hundreds of people in vintage plaid started waving their hands in unison.

The venue — a large fenced lot — was packed by then, and I wondered whether 90sFest was delivering on its Pog-centric advertising. “I think it’s pretty good for [the festival’s] first year — good turnout, good food,” Olivia had said. Her one critique? “I wish Shaggy was here.” Could 90sFest just be a pretty good way to spend a Saturday afternoon? There’s something to be said for a guy in a Where’s Waldo costume playing giant Jenga with his friends and having what looks like a kickass time. Those of us at the festival weren’t unaware that we’d paid $60 for the tickets and too much for Bud Light; we were being marketed to, but not necessarily duped. And for the first time, I felt real nostalgia: not for Rugrats or Steve Madden shoes, but for a time when I was less skeptical about buying the experiences I love.

Around 4:30, I weaved back through the crowd to watch Lisa Loeb perform under increasingly ominous clouds. After Perez Hilton introduced her — and talked up his role in the upcoming Full House musical — Loeb launched into her new material. The crowd chattered as if she wasn’t onstage. Admittedly, I didn’t find the new material gripping either, but I still cringed when I heard a woman behind me say what we were all thinking: “I don’t want to hear the new album stuff. I want to hear the old stuff.” As Loeb continued playing, a man beside me said, “Wow — look at her arms!”, presumably referring to Loeb’s toned biceps. A guy further back in the crowd shouted out: “I made my girlfriend buy your glasses!” How many of us have made sexual choices based on nineties pop icons?

When Loeb played the first chord of “Stay,” everyone paid attention. We all knew the words, and we all sang along. It was a beautiful moment in a bizarre context — the direct evidence of the song’s emotional impact, concentrated over time. And it struck me how unusual it is to hear the favorites of my childhood performed live; I was too young to go to concerts then, and my taste has changed now, so the songs hang, disembodied. Introducing “Stay,” Loeb said, “This song has taken me all over the world, so I always love to sing it.” The guy beside me smiled patronizingly. “Good for you, Lisa Loeb. Good for you,” he said.

The essentials of herd musicality are unchanged from my teenage experiences at Warped Tour — the back pain, the fickle weather, the smell of weed. Time, however, has brought us cellphones to hold aloft and earplugs to embrace. Most importantly, we could drink in this time-warped nineties, which lent the festival a messy undertone. By 5pm, a line had formed for the beer tent. The foam Rugrats got up on stage with some Spice Girls impersonators to do the Macarena, and people all around me started half-assedly flopping through the movements, Budweisers in one hand.

I found Joey, forty-one, watching the crowd warily. I asked whether the festival was living up to his expectations. “It’s kind of a big disappointment,” he said. “I feel like I’m in jail in the nineties,” he added, referring to the lack of in-and-out privileges. He preferred a recent Sugar Ray and Everclear concert that “was more like a regular concert. Less commercial.” In fact, his biggest beef with 90sFest was that “Nickelodeon is overrepresented and the U.K. as a whole is underrepresented.”

Joey was right that Nickelodeon was everywhere. It had been “sliming people” throughout the afternoon at a booth branded with the words “The Splat,” which was later announced as the name of its new all-nineties-all-the-time network. In the crowd, the “ewws” of childhood had been replaced with the calm remove of adults watching something ridiculous. “That looks water-based,” a guy behind me noted as one woman was splatted. His friend nodded. “Yeah, water-based.”

As dinner time approached, Pauly Shore bounced onstage again and delivered hype lines peppered with variations of “motherfuckin’.” The DJ — Suga Ray — played songs poached from Carson Daly-era TRL. Then Blind Melon took the stage and delivered a decent performance, with Travis Warren, the non-holographic replacement for deceased vocalist Shannon Hoon, singing “No Rain” to a crowd of people wishing for umbrellas. At 7:30, Pauly Shore got the Nickelodeon slime treatment, and left the podium looking a little annoyed. I sympathized, damp from the rain, re-living my worst nightmare of the nineties — standing in front of my male peers with limp bangs.

Darkness fell as we waited for Smash Mouth. A man beside me was using a Treasure Troll as a pocket square. People sang “a-yo, a-yo, a-yo, a-yo,” and I wondered how “No Diggity” has never been appropriated as a mayo jingle. I was surprised at my relief to see Pauly Shore take the stage in a new, even more brightly patterned suit. “Are you ready to smash your mouth or what?” he shouted.

Perhaps because of the rain delay, Smash Mouth wasted no time and launched straight into the favorites: “Can’t Get Enough of You Baby,” “I’m a Believer,” “Walkin’ on the Sun.” No one threw bread at them, so they didn’t swear at us. It was a serviceable performance but I couldn’t shake my longtime distaste for the band; I tried to picture them playing a small venue in the early nineties, people in the crowd saying “Damn! They’re gonna be big!” All around me, people were singing “All Star,” riding on each other’s shoulders. The band departed with a triumphant bow, then Pauly returned, shouting, “Yeah! That was sick!” The ground was paved with empty beer cans and crushed sunglasses. “Let’s give it up for god tonight, bringing us this beautiful moment. Praise god, praise the lord,” Pauly said. Then, shortly afterwards, “Play Weezer for the motherfuckin’ Weasel!”

By 9, I’d nearly had my fill of the nineties. I’d encountered a soggy fanny pack in the port-a-potties, and watched a drunk couple slow dance to Chumbawamba. But it was time for the festival’s headliners, Salt-N-Pepa, who exist in my memory as three songs: “Whatta Man,” “Let’s Talk About Sex,” and “Shoop.” They burst onto stage singing none of the above, but I couldn’t take my eyes off them: They had sparkly hats and male back-up dancers, coordinated dance moves for every song, and slick vocals. “I just wanna say, Salt-N-Pepa are coming up on our thirtieth anniversary,” Salt said. “And still got those sexy Tina Turner legs.” Then she told us, “This is not a show. This is a Salt-N-Pepa experience.”

That experience took us to “Let’s Talk About Sex,” with the back-up dancers spanking Pepa’s leather skirt. Then “Jump Around,” “Sweet Child of Mine,” and “Girls Just Wanna Have Fun,” during which Salt invited women up on stage to dance with her. She extended another offer during “Whatta Man,” calling up “all those good men out there.” Pauly Shore shimmied back onstage. Finally, they delivered high kicks during “Shoop,” their backup dancers bringing out the iconic leather jackets, white and yellow with red letters. Afterward, they got slimed — albeit, in plastic ponchos — and left the stage dripping green sludge. Whether by rain or slime, everything left 90sFest dampened.

Through the detritus of an exploded decade, I worked my way to the door. The Betches Bedroom had closed for the night; a man ran past to steal its Clueless poster. Walking toward the subway, I saw another man with the “#Betches Love the 90s” pillow tucked under his arm. We had literally looted the past. In some ways, I was glad we did. There was an element of camaraderie to 90sFest — people were reminiscing with friends, complimenting strangers’ outfits, exchanging knowing glances during Billboard hits. There were also times when the experience felt cheap, despite its expense — the blatant sponsor-plugs made me feel like we’d paid to take part in a giant Nickelodeon commercial.

Three days after the festival, 90sFest tweeted about “the next #90sFest.” The past is a resource that keeps on giving. I wonder though, will we still buy tickets after two years, five years, ten? Can our nostalgia sustain this festival indefinitely? If it can, I’m going to need more slap bracelets. And if it can’t, don’t worry: I’m sure someone’s working on #AughtsFest.

David Bowie, 1947-2016

There are times when a famous person passes away that your mind jumps to the friend of yours for whom that person had the most meaning. It says something about the significance of David Bowie, who died yesterday, that you probably know at least five or six people about whom you’re thinking, I hope he or she is okay this morning. There are probably five or six famous people you can think that of. If you are under the age of 40 you live in a world he helped make, whether you’re aware of it or not. His importance transcends his work in a way that only a few other artists of his generation can claim. Bowie was 69.