Lance Neptune, "Pyxis"

There’s something about this song that puts me in mind of a time when I could still convince myself that everything would be okay. It was a while back. Anyway, enjoy.

New York City, January 31, 2016

★★★★ Birds sang in the scaffold or shrubbery; tires pushed through the slush that still lay on the cross street. The outer playground was still blanketed with snow, but the concrete yard was clear. One pair of the four-year-old’s sneakers had been mislaid in the boots-and-shoes exchange days before, and now he was stomping in melt puddles with half of his one remaining pair as he scootered around. It was warm enough for him to ditch his parka and take to the swings in a tracksuit jacket, but not so warm that his hands weren’t chapped when he was done. People were sitting out on the luxury building’s roof deck in the sun, in their coats. Contrail after contrail after contrail traced the flight path across the west.

The Uber Job Fair

In New York City, where Uber just cut fares by fifteen percent, hundreds of drivers planned to go on strike today and demonstrate in front of the company’s Long Island City office, because they bear the up-front cost of such fare cuts. Uber, which argues that lower prices mean that drivers will ultimately make more money by ferrying more riders per hour, “believes in price cuts when demand slows down,” as one regional manager told Bloomberg when the company cut prices in eighty cities earlier this month.

Uber driver on strike in Long Island city New York @BCakaTheMan @chi1cabby pic.twitter.com/EGoQ0edZsO

— delaluxe (@delaluxe1) February 1, 2016

The interests of Uber and its drivers are not necessarily at cross-purposes here, but one of the ways that they are perpetually misaligned is that it is almost always in Uber’s interest to have largest possible supply of drivers, relative to user demand, at the lowest possible cost. Conversely, for drivers, the fewer of them on the road, the better, at least individually: It means there’s less competition for passengers, and if there’s few enough drivers that surge pricing is in effect, it also means higher wages. (There is a floor on this, though: There needs to be enough drivers in the network that riders can be reasonably assured that they will always get a ride for a price they’re willing to pay, otherwise they’ll choose another service or, like, find another way home, and then Uber and its drivers both lose.) Incidentally, this is why it’s difficult for a strike, unless it’s especially uniform, to impact Uber too drastically; further, the elegance of surge pricing as a mechanism extends to its ability to neutralize a strike by silently and efficiently enticing scabs to drive for higher fares.

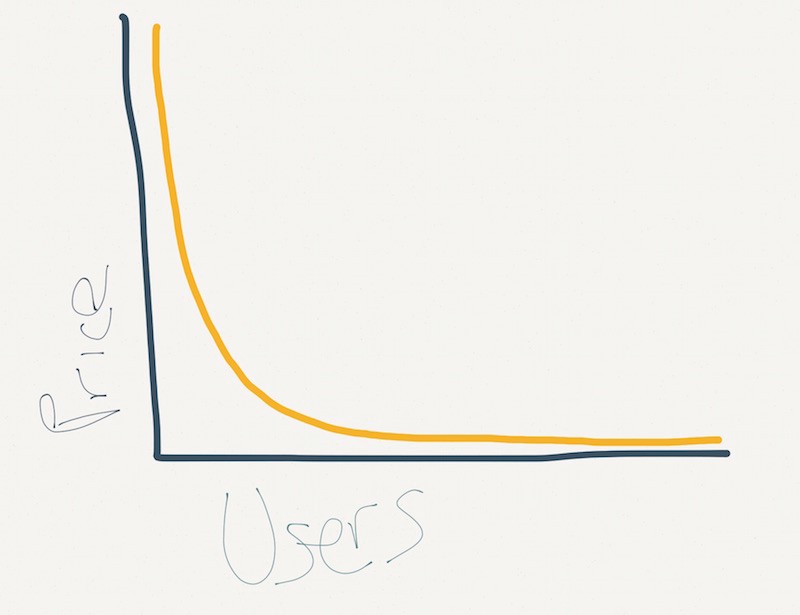

Anyway, while every company is generally incentivized to minimize costs, startups like Uber face a somewhat unique demand from their investors: the expectation of growing their userbase to a sufficient size to approach something like monopoly status, as quickly as possible, which essentially requires making their services free, or close to it. The virtuous cycle is the path from luxury service to indispensable utility: The cheaper Uber is, the more users it can sign up, and the more users it can sign up, the cheaper it can become, until it approaches ubiquity. So, as demand grows, Uber’s need for drivers is basically inexhaustible.

One of the unique things about New York City, and a handful of other areas with strong taxi systems or other professionalized driving markets, is that there is a large pool of existing drivers — or at least people who’ve thought about driving for work — from which Uber can potentially draw. In other, smaller cities, however, Uber must recruit more heavily from a pool of people who have never driven professionally, or even thought about it. In such markets, Uber has focussed its recruitment efforts in the last couple of years on old people, teachers, veterans, and, most recently,

laid-off Walmart employees (sorry, people “affected by last week’s store closures at Walmart”).

In other words, Uber seems to be specifically recruiting people who have been essentially failed by institutions, mostly public but also private: Older people who are too young to retire but can’t find another job, or whose retirement benefits are not enough to live on or pay for medical care, for any of a million possible reasons; teachers who can’t afford to not work a second job during the summer; veterans who have trouble transitioning to post-military careers because of insufficient support from the government; and employees left behind by America’s largest employer — though maybe Uber should target even Walmart employees who still have a job. (It is also maybe worth remarking upon that these are overwhelmingly white labor pools — reflecting, perhaps, the character of the markets where Uber most needs drivers.)

What’s most remarkable though is that even as Uber provides a legitimate salve for many of these people, its interests do not merely diverge from theirs after the point which it needs their labor to grow, but with nearly complete and utter transparency, it is working toward completely eliminating them in a matter of years. It will inevitably become another institution that fails them.

@danprimack fair enough… driverless in 2030 FTW… 🙂 /@MikeIsaac

— travis kalanick (@travisk) February 7, 2015

Of course, Uber has little choice in the matter: The utopic vision it is now pushing, where no one owns cars because nearly everyone is taken everywhere in efficient, omnisciently networked conveyances that arrive silently and immediately and practically — but not quite — for free, is only possible without human drivers in the mix. And it’s really hard to argue that we won’t be better off whenever that day arrives! But hopefully by then Paul Graham will have figured out how to pay everyone not to revolt — maybe basic incomes can surge whenever the demand to eat Paul Graham is at its highest.

This Play Brought to You by Powerball

Did you drift off to sleep last month thinking of how you’d spend your Powerball millions? What’d you come up with? The Edge’s Malibu mansion? Twitter dot com? The next Wu-Tang album? A night with Ted Danson? That’s cute. Roy Cockrum, a former monk, won a $249 million Powerball jackpot in 2014, and has been redistributing his newfound wealth by funding plays: “The Glory of the World” in in Louisville and New York; Tracy Letts’ “Mary Page Harlowe” at the Steppenwolf Theatre Company in Chicago; and a five-hour, three-intermission adaptation of Roberto Bolaño’s novel 2666, at Chicago’s Goodman Theatre, which starts its five-week run this weekend.

Two weeks ago, I spoke to Robert Falls and Seth Bockley, who adapted and directed the play, about the production’s history, how they got involved with Cockrum, and the difficulty of translating a five-part, nine-hundred-page novel into a stage production.

Who first wanted to do this adaptation, and why?

Robert Falls: I didn’t know anything about Bolaño until 2005 or 2006. I was in Barcelona, and was struck by these posters: A desert, a field, pink crosses, and just the numbers 2–6–6–6. They were all over the place. I don’t speak Spanish, and I asked a friend what was going on, and he explained it was the publication of the paperback of 2666, which had already been a huge success in Spain and throughout Europe when it was originally published. He told me about the book, even more about Bolaño, who was in the last years of his life. I found it an extraordinary story. When I finally read it, something about it struck me as quite theatrical. Even the fact that it’s in five parts seems to imply an epic quality that could be done in, let’s say, an hour an act. I worked on it, on and off for a couple of years, then I sort of said, “Well, I should get serious about it. But I need a collaborator, someone who knows more about adaptation than I do.”

Seth Bockley: Robert approached me out of the blue and asked if I was familiar with Bolaño. I had read The Savage Detectives,and the short stories in The Last Evenings on Earth, which I loved. And he said, did you read 2666? I had not. It was really kind of an open-ended question at that point. I’m a writer and director, but come from a literary background. I studied comparative literature, specifically Spanish as an undergraduate, so this project was a direct hit for me. I love adaptation. I really, really love the work of Bolaño. And of course this enormous challenge, which is how to bring this sprawling, kaleidoscopic, surreal, literary work to the stage.

Logistically, what are the first steps in taking a nine-hundred-page book and turning it into a production?

Falls: I began that process by trying to identify — emotionally and, in many ways, intellectually — what the themes were. It’s incredibly complex, but it wasn’t difficult for me to get it down to which characters seemed to be the most important. It’s not entirely character driven. It’s almost more thematically driven: It mirrors itself, there are echoes, the book goes off in incredibly different directions for hundreds of pages — things that, for a theater artist, it’s obvious you might want to lose. I did the first carving away, then passed it over to Seth.

Bockley: Form is a big question when you’re adapting literature for the stage, meaning, what are the theatrical devices you’re using to translate the mood, the intention, the narrative. That’s always my starting point, in addition to what characters may be our protagonists. The sense of place and world is what I love about this novel. I think theater is a wonderful medium for creating worlds, and the approach has been to craft these really different approaches. So, for the world of the academics in Part One (“The Part about the Critics” in the novel), we approached it as a universe of lecturing. That’s very much opposed to the brutal world of Part Four (“The Part about the Crimes”), where we’re presenting a series of scenes and forensic reports taking place in a hostile and sterile police office.

A five-hour play seems daunting from the audience’s perspective. Is that a tough length to work with?

Falls: I actually just came off a five-hour play, a production of Eugene O’Neill’s The Iceman Cometh. I almost used that as a model. I knew how that works, and also what keeps the audience in their seat. Can an audience see a five-hour play every week or month? No, I don’t think they can. We live in a time where lots of plays are eighty-five or eighty minutes long, single acts, but we’re also living in a time where the epic is part of our diet. It’s not a meal you want to have all the time. But it’s an interesting bonding experience when an audience comes in knowing they’re making a commitment of four, five, or ten, twelve hours. There’s a bonding they do with the performers, the piece itself, and the audience with them going through the experience.

Bockley: It is a form of binge-watching, isn’t it? I see it that way, as a chance to get lost in something, the same thing we do when we watch the entire season of Transparent in one sitting or one day. You’re giving yourself over to a big work or experience, and letting yourself get lost in it.

When I read reports about this, there was the mention of a Powerball lottery winner funding this. How important was that to the production?

Falls: That was essential. Even with the rights, which allowed us to pursue the writing and adaptation, we were never sure how to actually produce it. It’s extraordinarily expensive, a rather large cast of fifteen, a large physical production. I was worried about it being done in our main house of nine hundred seats because of the length, but I also couldn’t conceive of it in our smaller, two-hundred-and-fifty-seat theater because it would be too expensive. So we’d been going back and forth about how to produce this, and along came Roy Cockrum, who was a theater person who devoted himself to a monastic life, left that, and won the lottery.

Bockley: It’s a story worthy of Bolaño. The former actor and former monk supporting his parents, and one day, just buying a lottery ticket, winning hundreds of millions of dollars, and the first thing he does is support this adaptation.

Falls: Once he got the money, he said to himself, “I’ve always thought if I came into a load of cash I’d love to support ambitious and unusual theater productions.” He had been really taken with the work of the National Theater in Great Britain, adaptations with a lengthy rehearsal process. He said, “Why don’t I see more of this in the United States?” He realized, it’s resources, it’s money. So he created a foundation that was invitation-only. He knew my work, he knew the work of the Goodman, and we were among the first to sit down with him. He said, “Do you have any big, ambitious projects that can’t be produced without support?” And I said, “Boy do we have the project for you.”

Falls excused himself to leave for a meeting — not really worth mentioning, other than it explains his not answering the next batch of questions.

After Bolaño’s death, there were rumors about a sixth part of 2666. And the posthumously-released Woes of the True Policeman has crossovers with 2666. Also, there are the actual murders in Juarez that much of 2666 was based on. Did you use any of these or other outside materials?

Bockley: I have not read Woes of the True Policeman because, from what I understand, it is in some sense a first attempt at this novel. It has some of the same characters and overlaps, but I regard it as something of a first draft. 2666 is complete and has its own internal integrity, so I didn’t want to muddy the waters. That being said, I’ve read all of Bolaño’s other fiction and it does belong to a coherent universe. People call it the Bolañoverse. You’re asking if there were sources outside, and indeed, yes. For example, there’s a small moment in Part One where we’ve interpolated the figure of Auxilio Lacouture, the self-appointed mother of Mexican poetry, the leading character of his novel Amulet. As far as Juarez, as you know, Bolaño was never in Juarez around the time of the crimes. Bolaño’s own source was his friend Sergio Gonzalez Rodriguez, who appears as a character in Part Four. His book The Feminicide Machine was a major point of research and inspiration for us.

What’s been the most difficult part of the adaptation process?

A big challenge we’re just finally solving — that’s taken us years — is the timeline. Even something basic like, does Part Two happen before Part One? In an ordinary work, it would be extremely clear. In Bolaño’s, it’s thorny and difficult. For example, Part One begins with a bunch of dates. In 1993, they meet at a conference. In 1994, they meet up again. About halfway through, Bolaño stops using dates, so there’s an amount of detective work to figure out the literal chronological sequence. The second challenge is translating that to the audience.

You’ve been sitting with 2666 for longer than most people. Do you have an opinion of what the title actually means?

This is my pet theory. Two things: In Amulet, there’s a reference to the year 2666. It’s a very mysterious and poetic passage that talks about a cemetery in the year 2666. It’s completely oblique, poetic, dreamlike, but it suggests a kind of vanishing point, a point at which everything is forgotten. 2666 is a year in which everything we’ve seen is forgotten, all the people, all of the people’s names, everything about them. Another thing I like to think about is 1666 was called annus mirabilis, the Latin term for “the miraculous year,” by the English. It was a year in which many good things happened in the British empire. It’s a possibility Bolaño chose 2666 as an inversion of that construction. It’s a diabolical year, the opposite of the annus miabilis. It’s my crazy theory.

Two Thousand, "Algebra Chords"

This track seems throughout as if it is building up to a moment of intensity, and that at any second something different and jarring will happen to change everything, but actually you sit there listening in anticipation and all of a sudden it’s over. There’s no grand resolution: Things stay pretty much the way they are and then they’re done. I’m not saying it’s a metaphor for life, but I don’t think if I did say it was a metaphor for life anyone could accuse me of being completely off-base. Anyway, enjoy. Or don’t. It doesn’t matter either way. It’s gonna happen and then it’s going to end, whether you enjoy or not.

New York City, January 28, 2016

★★★ A sanitation crew with shovels was hacking apart a snowbank in the roadway on Broadway. The sidewalk was clean and dry. The gutter puddles were small enough and avoidable enough for sneakers. Between the blizzard and the clinging warmth before it, the ordinary non-waterproof cold-weather boots still hadn’t come down off the shelf. The place where the ceiling of the downtown Times Square N/R platform drips was dripping. The snow put a fresh dampness on the breeze. Brilliant white high clouds drifted north, as lowering golden sunlight covered the living-room wall and flashed on windows miles away.

The Afronauts

by Adwoa Afful

Ghanaian filmmaker Frances Bodomo’s beautifully shot short film, Afronauts, tells an alternative history of the nineteen sixties Zambian space program, the brainchild of Edward Makuka Nkoloso. A World War II veteran and school teacher, Nkoloso founded the Zambia National Academy of Science, Space Research and Philosophy and conscripted twelve astronauts into the country’s race to the moon, including Matha Mwambwa, a seventeen-year-old girl who eventually become the program’s lead cadet. Released in 2014, Bodomo is currently working on adapting Afronauts into a full-length feature, and we talked a couple of times over the last few months about her experiences as an African filmmaker in America, gender, migration, science fiction, and the narrative space between history and myth.

How would you describe yourself and what you do? What attracted you to filmmaking?

Who am I? I’m just a person that’s learning a lot or changing a lot right now. I’m going through a really transformative moment. Like earlier on, I really felt like I had a lot to explain. I wanted to explain to a wider audience — to everybody who misunderstood me let’s say. And now I’m learning that I would like to be in dialogue with people who are asking me to express rather than explain myself.

How did you get into sci-fi? Who are your influences?

I’m a long-time sci-fi fan who is really into Octavia Butler and Phillip K. Dick and has seen every version of Blade Runner that exists. I became obsessed with films in which the world and production design tell the story, adding multiple layers of subtext to the plot/dialogue. When I heard the Afronauts story, it felt like one that was inherently cinematic: It had to be shown rather than told.

Afronauts is definitely part of a wider lo-fi sci-fi trend happening in African cinema and I love everything I’ve seen, Pumzi especially; I’m excited to see the Ethiopian film, Crumbs.

There seems to be growing interest in sci-fi across the continent, but lately East Africa, specifically Ethiopia and Kenya, Ghana, Nigeria, and South Africa has been dominating the landscape. Why do you think that is? Where do you see your work fitting in?

You mentioned just about all of sub-saharan Africa! I do think it’s a cross-continental phenomenon. It’s the logical result of a generation of image-makers who come from the goal of “changing the view/stereotypes of the continent.” A lot of us started with that goal. In my experience, that goal got boring. I was constantly trying to validate the continent, which necessitated it be monolithic. It got boring, and it didn’t feel true. We’re seeing sci-fi “dominate” because it’s more fun, playful, and truthful to imagine/explore/express. It’s more discursive, more radical, to look at your creative peers and say, “What if?” We create something new that way, not from explaining ourselves, but expressing ourselves.

Sci-fi, especially now, is often about nostalgia, but nostalgia can sometimes leave its storytellers and audiences with certain expectations when it comes to the type of stories that can be told and who the protagonists should be. For instance, when it was revealed that one of the lead character’s, Finn, in the new Star Wars film would be played by British-Nigerian actor John Boyega, there was some backlash from Star Wars fans about that decision. How do you think films like yours, and maybe African sci-fi more generally, can help upend those expectations? Is that even a goal of yours?

I don’t agree that sci-fi is inherently about nostalgia. Period pieces are more inherently nostalgic. That Star Wars fans lashed out against Boyega’s casting to me isn’t nostalgic — simply racist. It needs to stay was because the world used to be like this, is simply a thinly veiled excuse for racism. They don’t want to see a black face in a world that previously reflected their whitewashed reality.

I don’t really feel the need to upend this sort of expectation. I’m telling a story and I hope to tell it truthfully. If a person goes in with racist expectations and those are upended, good! If a person comes out feeling like they’ve never seen themselves on the screen like this, even better!

Afronauts was screened at Sundance in 2014, but the people who might most be able to appreciate the experiences portrayed in the film, specifically people of Zambian and perhaps recent African descent — they might not be able to see it, right? Is there potential for wider distribution?

Short answer, yes, there will hopefully be wider distribution, simply because distribution for shorts is not really a big thing. But, by the way, the film has played in: Congo, South Africa, Nigeria, Kenya, Ghana. You bring up a good point about audience and space, but I think it’s a big assumption to say, “people who appreciate the experiences portrayed.” I’m not planning to shy away from the film being about Zambians and Zambians specifically, but I should hope the film speaks to a wider audience. I want to tell stories in which people grapple with themselves. Not ones in which people simply see themselves and appreciate it and feel good. Representation matters only if it’s engaging, challenging, complex. Not simply because it’s present. We see the fault of this sort of thinking time and time again: Finn was in Star Wars but what did he really do? So many strong female superheroes doing nothing. Another way of saying this is: I’ve seen myself in white male stories my whole life. It’s time for them to experience seeing themselves in my story, which takes a lot of translation-free, authentic storytelling.

Right now you’re on a research trip for the feature version of Afronauts. As part of your trip you’re visiting several countries, including Zambia. What can we expect from the feature that will be different from the short film?

Many things! This one is going to be an essay so I decline to answer 😛

In a recent piece for the New Yorker, writer Alexis Okeowo wrote about how a lot of films that focus on Africa, in order to appeal to an international (read Western) audience, have to be “message films,” in that the films have to focus on a “cause” that needs immediate attention. Your film does not fit that criteria at all. Are you concerned about how the film will be received by audiences outside Africa because of that, especially since the themes in your film are ambiguous and irreducible to any one “message” or cause? Do you think working within sci-fi exempts you from that burden as a filmmaker?

Short answer: I don’t care.

Basically, as an artist, this is not how I go about choosing how to tell my stories. A filmmaker friend once told me, when I was worried about future audiences not “getting” a film I was trying to make, that I was “assuming a lot.” He said, “you’re assuming those people are even coming to see your film.” That meant a lot to me. Look, film is a business & I know my audience. But there’s not world in which I get to tell this story the way I want to tell it and appeal to “everybody.” In film, “everybody” is Eurocentric and necessitates me shifting my process from creative to plotting/planning. I’m a filmmaker, not a strategist. I’ve tried to be “smart” and “strategic” and it has always led to a painful void & loss of desire to make films. I focus elsewhere now.

What I find remarkable about African sci-fi is the sheer diversity of the stories being told about various African societies, especially in literature (i.e., Nnedi Okorafor, Diriye Osman, Lauren Beukes). And yet, for many people, at least in the diaspora and the West, the face of African sci-fi in film is still South African filmmaker, Neil Blomkamp, with his film, District 9. Do you feel that awareness of films and a more diverse set of filmmakers from other parts of the continent and the diaspora is catching up to their literary counterparts?

We’re so early with all this stuff, let’s let it grow. Yes, people go immediately for District 9…that’s a budget thing. But imagine Kibwe Tavares’ JONAH is made into a feature! I’m sure if we give audiences more to talk about, they’ll talk. That takes time. I’m down to not overthink it. See what happens. Maybe we get more big-budget sci-fi films from the African continent. Or maybe we get something that is as of yet unimaginable! Even better!

You were born in Ghana, spent some time in Norway, moved to California when you were young and now you are based in New York. Some of the recurring themes in Afronauts have to do with family, home, and migration even though it’s in the larger contexts of the Zambian space program and decolonization. Did your background inform the narrative you tell in Afronauts? If so, to what extend and how?

I think that based on my background, home becomes this sort of impossible place. Finding home could be the purpose of life, but to me, home — because of my background — that question is like the search for the impossible. For me, you hear about the Afronauts, you hear about people trying to go to the moon, and there are so many reasons why they won’t. There’s something about that premise, because a lot people hear that and they’re like, “Why would they even try? We know that they’re not gonna make it.”

But to me it’s sort of like you hear this story and you’re with them, you’re with that desire, you’re with being up against all odds, you’re with their underdog narrative, and that’s a ride I want to take people on. Because I think when you grow up an outsider there are so many things that seem unreasonable. When you’re talking about this sort of global nomad, this childhood, you see a lot of unreasonable things, a lot of instances where reason has failed people. I mean you don’t grow up with a universal norm that is then broken, you grow up with a norm that’s always in flux. And so it’s an awesome thing to take people along for that ride. We know that Neil Armstrong was the first person to land his foot on the moon; we know that the rocket that they’re in doesn’t look like it’s going to make it to the moon, but I’m along for this ride. In the feature film, I hope that after you take that ride when that rocket comes crashing down, you’re as sad as the people in the movie.

One of the things that kind of struck me about that film is that it was almost nostalgic in a way. The moon landing represents the height of US ingenuity and potential and there is this sense that the comedown from that moment was hard. Now it takes on this new more ambivalent historical importance. Was that something you were thinking of when you were making the film?

It’s interesting. It’s not something that came to me, but it’s been brought up a lot by Americans. One of my grant givers said that it’s interesting that you set it up like here is a triumphant moments for the Americans, but it was a sadder moment for your characters. I guess he was like when Americans see rockets going up and landing on the moon now it’s like they remember Voyager and all of the crashes that happened, the moments after 1969. That image for Americans right now is a very ambivalent image, you know? Americans aren’t even sending people up to the moon anymore or into space. Now it’s like these robots.

I do think that the historical moment of this movie is really important, and in 2015 these are things we can talk about. but 1965, 1969, was a triumphant moment. That was the narrative the characters are reckoning with. You know that’s what enables the movie to work. In 2015, Afronauts is another kind of story, the important thing is that America has not won yet in that era where anybody can try.

The real Edward Nkoloso was very interested in creating this program as a kind of nation-building project in Zambia, and so it’s kind of like the character in the movie is recreating that first moment of contact between Zambians and their colonizers. He’s recreating that history of colonization, but in a way that wasn’t as it actually happened.

Yeah, I hear that. I’m turning this into a feature film, so you’re hitting on a big, big theme, that’s in the feature, which is that these people and this guy starts really wanting to validate himself under what I’m going to call a Western gaze. The idea that to define your new nation you have to join the space race is one way of saying that we’re going to become valid in your gaze and that’s a dynamic that can only recreate violence. That’s played out in the idea that Matha is actually going to have to go on a suicide mission — that violence is being created in what is being expected from Matha. And so the shift that has to happen is not saying we want regard from the West to validate our new nation, but we’re already awesome.

A question people ask when you become a new nation is how can you rebuild a new nation when nobody that’s alive saw a pre-colonial Zambia, you know? Like in 1964 when Zambia became independent, even the oldest people in the country were born under colonized Zambia, and it’s like what are we rebuilding at this point. That’s a really hard question to ask; that’s a very hard thing to deal with. Because even if people remembered, we’re then reckoning with varied ideas of what a pre- British rule Zambia was. It’s a very painful thing to realize that you’ve lost a certain history, and I think that, because of that, people go into these neo-colonial missions — re-creating a certain violence. I thought that as it plays out in Matha’s character, that cycle is going to be broken in the film. I’m still writing, so I don’t know yet.

I noticed that these two women fit into these two different archetypes. The Nkoloso character calls Matha his “space girl,” she’s kind of loses more of her agency the more she participates in this program, whereas the other woman is kind of the mother-ish figure who helps bring Matha closer to the vision that she and Nkoloso are trying to realize. Was that a contrast that you had intentionally put in the film and how does that fit in with its bigger themes?

I think with the men in the film they really bigged her up to this myth — this mother of the exiles and that becomes quite fetishistic almost. My immediate assumption was that the aunty character gets who [Matha] is and was actually scared for her blood and bones. She’s not with it to put this girl in a rocket to prove to the West that they’re worthy. But, to me, the emotional thing that happens there is that she airs her grievances and Matha says she still wants to go, and so she just has to step back and watch it happen, which is a painful thing to do, but that’s the thing that you do when you respect somebody’s agency. Even though it’s a really sad thing to stand by and watch her enter that rocket, she is the only person here that treats Matha like a person with agency, worthy of deciding what she wants for herself, which is a hard thing to do.

I want to switch gears now and talk to you about where the short was filmed. You had mentioned in other interviews that you would have liked to have shot the film in Zambia, but it would have been too expensive. You ended up filming in New Jersey instead, but one of the more remarkable things about that space is that it really does look like what you would imagine the surface of the moon to look like. How did having to shoot there help you explore different ways for telling your story or exploring the themes you wanted to explore?

It’s something I’m thinking a lot about, because Zambia’s landscape isn’t really arid desert; it’s not really desolate. And this where the sci-fi comes into it, because you can take liberties and telling an alternative history comes into to it. You know it’s wonderful that they’re already on this landscape that already feels like the moon, that already feels like they’re already where they’re going. That feels like the message at the end of the film, that they’re already where they always wanted to be. The loneliness and the pain and the self-negation that exists here is what it’s going to be up there. The trials and tribulations here are going to be up there. Visually, they’re already in their dream space. I guess it’s me being cynical about having dreams.

That’s really interesting to me, because I’m of Ghanaian descent as well, and one of my experiences growing up — and maybe for you as well — was that the US got romanticised in a lot of ways within Ghanaian immigrant communities. And with sci-fi, this idea of space as the new frontier can also serve as an analogy for that aspect of that migrant experience. This idea that things are not going great here, but there’s this other place that we can realize our dreams and hopes and you get there and it’s like, oh, it’s not exactly that. So I was wondering if in your film if you saw space travel as a way of explaining that transient migrant experience?

Yeah. My first film was about the migrant experience, and with this film it’s the same migrant story, but on a super-planetary level. Ultimately, my film isn’t about the immigrant experience, but any sort of migrant experience. The story is about the shift from being aspirational to being self-worthy. There is a lot of the fetishization — a lot of immigrants travel with this idea of upward movement. That is why you emigrate, you believe your life with be better over there. But to me, the beginning should be “I’m worthy.” I’m rambling here, but I would like to see that typical immigrant narrative shift from one of aspiration to being seated in your own self-worth.

You have talked about navigating the film industry as an African and female filmmaker. You have suggested that perhaps being African has meant that you navigate the industry differently than if you were seen as just a woman filmmaker. Could you talk to that a bit more?

You can’t win basically, either way, but when it comes to African filmmakers, African diaspora filmmakers specifically, I think that in the film festival circuit there are just so many women making movies. It’s a majority women that you see in these spaces.

Really?

Oh yeah, there’s Akosua Adoma Owusu and Shirley Frimpong-Manso. You can be successful like how Ava Duvernay’s successful to a certain extent, but the movies I want to make aren’t civil rights period pieces where MLK is an upstanding man. It’s wonderful that she was able to tell a movie where he’s humanized, but at the same time, I’m more interested in seeing somebody that’s not necessarily perfect and having to work with that. I’m not interested in telling a civil rights or a slave movie; it’s not a narrative I interact with necessarily.

You’re African-American, but of recent African decent, a distinction that implies a unique set of experiences. So how do you plan to tell stories with that kind of nuance?

The nuance for me is a loss of home, the nuance for me is an African in America who’s looking back to Africa with love. And that is the emotional space that I want to explore. Exploring the loss of home, that you can’t go home again, a sort of impossible search. I do see what you’re saying, this sort of cachet — it’s very common right now that Africans, especially British Africans, are getting the big roles. It’s like the Steve McQueens and the Chiwetal Ejiafors, these people seem to be getting more access within Hollywood than African-Americans, you know what I mean? Though I technically fit into that, I definitely read more as an African-American. When I walk into a room and they hear my accent, nobody thinks of me as African and so it’s something I have to state and call out. This idea that you’ve been robbed from your home, and this looking to your home in a paradise sense and having that be complicated.

This interview has been edited and condensed for length and clarity.

Images from Afronauts courtesy Powder Room Films

The Mall of the Wild

by Benjamin Reeves

It’s impossible to talk about modern zoos without talking about modern environmental crises — global warming, habitat loss, extinction — but zoos are also these kind of strange, liminal spaces that connect people and cities with wildlife, as David Grazian, an associate professor of sociology at the University of Pennsylvania, explains in his latest book, American Zoo. Zoos, in essence, are a physical manifestation of the way that people have tried to separate themselves from the wild — which of course reveal how our very concept of “nature” is a social construct.

Grazian lives in New York City, so I met him Think Coffee, a coffee shop rife with undergrads in one of their daytime natural habitats, to talk about wild animals and concrete jungles and zoo weddings.

What was your research method when you went into a zoo?

The two zoos where I did the bulk of my observations, I signed on as a volunteer. I got to know people pretty well; I told them that I was a college professor and I was interested in learning about zoos. Over time I got to spend four years at two different zoos, cleaning animal enclosures, preparing animal diets, learning how to handle zoo animals and display them to the public.

Did people know you were writing a book?

They knew that I was doing research. Obviously, when you’re in the middle of research, you don’t know what it’s going to turn into and you don’t know if you’re going to have enough for a book until the whole thing is over. So you can’t really approach people on the first day and say you’re writing a book.

Before this, you were doing research on the late-night blues scene. How did you make the transition?

In 2006 my son was born, so it was no longer all that feasible or desirable for me to go out to cocktail lounges until four in the morning. But I did find myself going to the zoo every weekend, taking my son, as any parent would. So I found myself in this space and was struck by all of the interesting similarities between zoos and nightlife establishments and not just the fact that they’re both places where you can observe strange mating habits in public. They’re places where authenticity is culturally performed for an audience. They’re places that people invest with meaning.

The idea is that someone who comes through the doors already has expectations about what they’re going to get. If I go to the Blue Note I have an expectation that I’m going to hear jazz. Same thing at the zoo, everyone goes and expects to see the bears and the penguins.

And everybody expects the animals to act in all sorts of ways that they wouldn’t necessarily act in the wild. Ultimately they get disappointed when they discover that the lion is sleeping even though a lion in the wild rests twenty hours a day.

It’s not fake for a dog to live in someone’s apartment. It’s not fake to keep animals that are endangered in the wild in sanctuaries in the United States. But you’re not seeing animals in some kind of virgin, unadulterated state. You’re seeing animals in a human institution, a social institution. Generally speaking, zoos do operate in the best interest of animals. Zookeepers were among the most committed animal lovers that I’ve ever met. But sometimes what’s in the best interest of an animal may not seem that way to a lay audience.

One day that I was at the zoo, someone was having a wedding. On the one had it’s kind of cool. They’ve got the big trees and the architecture and the animals, right? But on the other hand, parts of the zoo smell like poop; if you go by the penguin enclosure, it smells like fish. There are barriers around the exhibits, and you think, that’s to keep the bear away from the people, but it’s also to keep the people away from the bear. How do people think of zoos as places to get married but they would also take a four-year-old to eat ice cream and look at a monkey?

There’s a real value to taking children to zoos to see animals up close, particularly if we want to help children develop an appreciation of the natural world and the sense that we humans are not alone on the earth — and that we have an obligation to protect the earth. I know of no more convincing way to teach someone about human evolution than to have them look into the face of a gorilla or or a chimpanzee.

My own personal opinion is that when zoos stray from a message of conservation — providing a sanctuary for endangered animals, animals that are injured in the wild, a place of education — zoos go astray when they use their exhibits simply as a sort of theatrical wall paper for a fundraiser or for a wedding. There are many zoos that are privatized and for-profit; Disney’s Animal Kingdom, for instance, can presumably do whatever it wants with its space.

But plenty of zoos, even private institutions, if they have non-profit, tax-exempt status, ought to serve the public accommodation, rather than the space being bid out and auctioned to the highest bidder. If zoos lose this fundamental purpose of educating, of inspiring, of teaching about the importance of biodiversity, of warning of the dangers of the climate change crisis, then zoos no longer have a warrant for keeping animals in captivity in such close quarters.

Yet zoo-goers are an audience. Death, predation especially, that’s not really something you’re putting on display. Vomit and excrement are covered up and hidden. The way life actually exists is concealed.

A lot of the realities of simple biology are censored from the visitors’ experience in order to create a kind of idealized experience that is staged than authentic.

You talk about zoos in the South where there’s discomfort over teaching and presenting evolution as well.

Not only zoos in the South. You see that in most zoos across the country, but particularly in the Bible Belt. I saw a reluctance to talk about human evolution in all sorts of contexts all over the country.

I mean, are they worried that no one is going to come to the zoo?

Obviously the scientists that work at zoos believe in the tenets of human evolution, as all scientists do. But one of the challenges that zoos face is that because they are so reliant on revenue that comes through the turnstile, and given that they attract such a mass audience of people from all backgrounds and education levels, they tend to be very timid — and I think cowardly — when it comes to teaching the public about issues that have been deemed controversial like climate change, like evolution, even though they’re basic scientific facts.

The Central Park Zoo is in the middle of Manhattan. The Park’s been sculpted, by Olmstead, but there are tons and tons of wild animals that live in there. In my part of the park we have loads of raccoons. So people will go to a zoo and look at a coati, for instance, which are related to the raccoon. People, my wife included, get all excited. (You’re right, it’s a place you take dates.) We’re walking home, and there’s a raccoon taking half a chicken out of a garbage can. People are reacting as if it’s some kind of negative thing that’s encroaching on them, even though it’s no different than what’s in the zoo.

Actually you’re witnessing animals that are truly autonomous.

It’s not just in Central Park. The city is full of pigeons. It’s full of red tail hawks, of course rats. The city is an ecosystem. The city is a jungle.

But there is this real discomfort at encountering an animal in the wild, especially for people who live in cities or suburbia.

Certainly. Part of that is because wild animals in the ambient environment are untamed. Humans aren’t protected from them. Very often they are species that are everyday parts of the urban environment that are therefore accorded a very low status. Often thought of in other contexts as pests or as vermin, as carriers of disease. What’s interesting is that in the zoo children are often as excited by seeing wild, untamed squirrels or pigeons as they are by the animals in captivity.

At this point An NYU undergrad in a deliberately frayed stocking cap — he looks like he’s probably reading Nietzsche for the first time and making lots of profound discoveries — walked up. “Excuse me, you’re talking really loudly,” he said. “Can you be quiet? People are studying here. Thank you.”

Is it a library? Are we not allowed to speak in public?

“Can lower your voice?”

Were you asking or demanding? It sounds like your demanding.

“It’s a public place. So keep it that way.”

That seemed really uncalled for actually, I don’t like your tone.

The student left.

I forgot about the attitude problems at NYU.

He said it’s a public place, keep it that way? So we can’t talk? If it’s a public place, then it’s a place for conversation. It’s not like I’m on my cell phone having a loud conversation.

You’re right.

Well, also, it was like a directive. It’s sort of stupid. He’s an NYU student, and he doesn’t know if I’m a professor at NYU.

Where were we?

Kids haven’t been socialized to think about these socially constructed boundaries between the human world and the natural world. Those [squirrels, raccoons, pigeons] are also animals that are — because they’re on a smaller scale — much more inviting to kids. Children’s literature is full of the anthropomorphizing of all sorts of creatures, like raccoons and squirrels and rabbits.

Do you think kids recognize that there’s a difference in the animals that wander in and the ones that live in zoo?

I’m not a child psychologist, so it’s hard for me to know. When they see those animals, they react with delight. It’s clear to me that children often have to be taught by their parents that a zoo is a kind of environment where animals are in captivity.

And that’s somehow different than the animal in the park or being at home and seeing the family dog.

Children certainly seem delighted by these sorts of small creatures. But children are delighted by all sorts of creatures that their parents don’t find all that enchanting. Children appear to show much more interest in insects — not only butterflies, but cockroaches, spiders — much more so than their parents. They haven’t been socialized to recognize these manufactured, symbolic boundaries between one type of animal and another.

If you read medieval texts they talk about the wild and everything out there, and then there’s the holdfast and the farm, and that’s what we can control in here. People carried that mindset into the modern era.

For most of human history, the wilderness has been something to be feared. Just ask Little Red Riding Hood or the Wandering Israelites. It’s only really been in the last two hundred years or so that humans have begun to re-conceptualize the wilderness as something sacred, as something worthy of being protected, as something that invokes inspiration and awe. The very way that we think about and socially define the natural world is historically determined and socially constructed in a way that would probably not be recognizable to most generations of humans up until modern times.

The origins of zoos go back to the Victorian period. Their origins were in a previous era during a period of industrialization and railroad building and taking control of rivers and the natural world; the creation of zoos mirrored the creation of national parks in the U.S. with Roosevelt. Do zoo have to modernize or change?

There’s a real difference between the motivations for creating the zoos of the early nineteenth century in Europe and American zoos which emerged in the late nineteenth century. In the United States, zoos emerged during the beginnings of what we could call the American conservation movement of the mid-nineteenth century, inspired by people like Audubon and Teddy Roosevelt and the development of the national parks, the interior department. Many zoos, the Bronx Zoo, were created with an eye toward saving the American bison.

Today, zoos have no choice but to adapt, or they won’t survive. By the nineteen seventies the environmental movement was ascendant. Americans had clearly become interested in the welfare of the animals. The old-fashioned zoo was no longer going to cut it. People were no longer going to tolerate seeing animals in concrete cages with iron bars in closed quarters. At the same time a whole set of international laws made it impossible to collect endangered species in the wild, so zoos had no choice but to rely on captive breeding programs.

In order to survive, zoos needed to create naturalistic zoo exhibits, or they would otherwise alienate everyday Americans that want to see captive animals as comfortable as possible. By the same token, in an era of environmental crisis, on a planet beset by massive species extinction, biodiversity loss and habitat destruction, zoos have a moral imperative to sound the alarms. I think they know this.

A lot of the changes in zoos come from within, particularly as zoos started hiring more scientists and as zoo-keeping became more a caretaking job as opposed to one of human dominance over animals. So within zoos, there’s a real sort of push to create scenically attractive, aesthetically beautiful, edifying exhibits that harken to a kind of scientific realism that can inspire and educate mass audiences about the importance of wildlife conservation. It’s incumbent on zoos to lead in this capacity and lean in as far as they can without fear of alienating religious groups that might be disturbed by the realities of human evolution or conservative climate change sceptics.

Is there a risk that people abstractly hear that pandas, for instance, are endangered but they kind or know that they can go to the national zoo or log-on to the panda cam and see one?

I have to think that there’s a kind of consciousness around the endangerment of pandas. There’s a reason why the World Wildlife Fund uses the panda as a mascot. They use the symbolic power of a beloved creature in order to talk about environmental devastation, habitat loss, and in some ways, it’s those animals that people cherish the most that will motivate people to learn more about the environmental crisis.

When you were starting this project did it ever feel subversive to go into a zoo and observe the people? Did you feel like you were transgressing what zoos were for in doing that, since people go to zoos to look at animals.

I guess there is something subversive about turning the gaze onto the visitor. On the other hand, I think that the social scientist’s intentions are generally to increase greater understanding about how humans behave and interact in the world. That’s very different than ogling an animal in a cage because you feel superior to it. As an ethnographer I also know that I have my own sets of human prejudices and desires. I too am attracted to active rather than passive animals.

What are you doing next?

Well, my son is sick of zoos. I think I wore him out. We went to too many.

How many did you go to?

We traveled to twenty-six zoos across the country. The zookeepers got to know him — he got special privileges when we went to zoos. He sometimes got to peak behind the scenes, not in a way that would be dangerous.

You’re not putting him in the lion pit or something.

Even the zookeepers don’t go into the lion enclosures by themselves unless the animal is tranquilized or dead.

So you’re not sick of zoos yet.

What I’m leaning more toward now is thinking more generally about nature in the city and the blurry boundaries between the natural environment and the urban environment, particularly in places like New York; Manhattan is surrounded by rivers. We’re surrounded by domesticated environments like botanical gardens but also wild habitats.

This interview has been edited and condensed for length and clarity.

Photo by volna80

Apes, "Mosaic"

Nothing gets better. If you’re lucky, things don’t get much worse. Do you feel lucky? Me neither. Anyway, whatever kind of day you’re going to have, this song will at least not make it much worse. There’s something to be said for that in this time of things not getting better. Enjoy.

New York City, January 27, 2016

★★★ Stretching out from the northwestern corner of the glass tower’s low-rise terrace, a curving bay of newly bare paving tiles had reduced the untouched snowpack to an isthmus. Ever-larger serrations in the coastline followed the pattern of the row of planter boxes. Down on the cross street, an uncollected trash bag had slid down the back side of the snowbank, narrowing the already narrow sidewalk even more, just at the point where a squished dog turd lay. The rubber-bottomed boots were a little too hot indoors. An airplane cut an uncanny reverse contrail through a thin sheet of cloud. Then the sheets broke up and clumped into little high thin segments, blowing north, even as low fluffy shreds of cloud blew south below them, the whole sky going retrograde. Before day’s end, it had all settled into an ordinary and orderly flock of cumulus.