The Gawker Lunchtime Walkout Is Cancelled, BTW

As of last week, the Gawker editorial union was planning to walk out and take the sites dark this Wednesday because management would not negotiate over a guaranteed annual cost of living salary increase — the union had asked for around six percent, management offered zero. Well, the walkout threat maybe… worked? Because we’ve heard from a few people that the walkout has been cancelled, for now, with everyone returning to the negotiating table. Good job, everybody.

Photo by Cory Doctorow

Prins Thomas, "A2"

Let’s just try to sneak into this week without drawing too much attention to ourselves, okay? Once we’re safely settled in we can figure a way to quietly get out of it but for now everyone should do their best to be as unobtrusive as possible, because as stupid and loud as the weekend was things are about to get so much worse over the next few days. Anyway, relax and enjoy and for God’s sake, be quiet.

New York City, February 4, 2016

★★ One last snowbank still looked like a snowbank; the next one was just a little clump of ice chips on the wet mulch. The downpour of yesterday was an oily little puddle at the foot of the subway stairs. The daylight had not been strong enough to rouse a sleeper with the blinds up, and it wasn’t getting much stronger. The cloud cover faltered only a little around midday, then re-thickened. The thin, unlined hoodie was a mistake by the ride home, but not a serious one. A bedtime glance at the weather forecast found an unexpected exclamation point there, and not long after came the sound of something frozen hitting the windows.

Upload Complete

In January, following a year of stalled growth and financial disappointment, Twitter shed nearly half of its core leadership. Three days later, Adam Bain, the company’s (surviving!) Chief Operating Officer, posted this complaint:

“Code for Twitter” https://t.co/pZdbJNx67J

— adam bain (@adambain) January 28, 2016

The linked tweet:

Wherein Facebook editorializes the Kanye Wiz ordeal as “a series of posts on social media.” 😂😂😂 pic.twitter.com/RVCZ5kE4fO

— Josh Williams (@jw) January 28, 2016

That day, Kanye West and Wiz Khalifa had gotten into a fight on Twitter, roping in Amber Rose and setting off a massive and spontaneous celebrity media event. The choice of medium was a notable and conspicuous part of the story: West’s Twitter presence is uneven but legendary; one of his posts (erroneously) mocked Khalifa for losing followers; he mentioned looking at Khalifa’s timeline. It’s where responses were expected to show up, and did.

An editor at Facebook, confronted with an unignorably viral disturbance that originated entirely outside the platform, wrote up the event for Facebook’s trending news service as “a series of posts on social media,” dropping a couple proper nouns, both of which start with the letter T. Bain, citing further examples of feed-washing from Facebook, joked: “Working on changing my business card to: COO of Social Media,” and linked to this tweet:

Facebook must have some sort of algorithm tweak that changes every instance of “twitter” to “social media” pic.twitter.com/nAm3aNMtts

— ಠ_ಠ (@MikeIsaac) January 28, 2016

Whether you think Twitter is dead or dying or misunderstood and undervalued, a competitor’s sidebar attribution practices seem like a petty thing for its COO to be focusing on right now. (“Hey… Facebook… ᔥ much? Yeah well ↬ you!!!”) But the complaint speaks to a set of real anxieties burbling underneath the various structures and businesses that make up the popular internet, and Twitter in particular. On a near-future internet broken into increasingly self-sufficient platforms, territory, borders and ownership will matter a great deal. Twitter has to stake its claim.

Back when Twitter made of point of calling itself the “global town square” at every possible opportunity, most noticeably as it was preparing to go public, the claim contained a grain of truth. Twitter was a place that allowed people to congregate on-platform in ways they wouldn’t have been able to before. It was a community unto itself, and a productive one. But it was also, largely, a place for people to talk about other stuff online. It was a public comment section for the web. Twitter’s growth years were about a lot of things: celebrities, activism, news. They were also about links. In 2012, Twitter was big. And important! But it was still just one part of the actual global town square, just one especially large and coherent website of many.

Even then, though, a major shift in online power was already well under way: from computers to phones; from sites to apps; from an intoxicatingly wild and decentralized mess (the web, websites, links, etc., managed by loose shared standards and accessed in browsers) to a few intoxicatingly huge managed populations (the platforms, managed by themselves and accessed in apps). In 2016, the still-vast and still-growing web is comparatively diminished. Slightly newer platforms, such as Instagram and Vine, hardly touch it; Snapchat doesn’t even acknowledge it. A now-ubiquitous Facebook, meanwhile, has gradually replaced, within its platform, parts of the web its users shared most: outside videos; outside articles; outside personal sites; outside listings; outside streams; soon, maybe, outside audio streams. Twitter, slowly and with less leverage, has been doing the same: a feed of text and links has become a feed of photos, videos, audio, and, next, posts over 140 characters. The platforms that came of age on the web are leaving it behind.

Most of the material clashes between Facebook and Twitter have been minor. Remember when Instagram images expanded automatically inside tweets? That was nice! It also amounted to the direct and constant promotion of a competing service, or, from Instagram’s perspective, the large-scale use of another service’s content. But such withdrawals, which occurred during a time when the companies’ feeds were becoming more visually and functionally alike, were insignificant in comparison to what the services still shared: an outside media fostered, divided and fueled by a vast and agnostic web. The services were distinct in many ways, but the manner in which they processed and displayed the same material was a significant one. Posts from the same sites. Videos from the same YouTube. A world of media laundered into feeds by links.

A feed, then, was a mixture of personal posts and pitches to look at other things. It was an endless stream of captions contextualizing a Great Big Outside. But each year the feeds got richer. The captions expanded into previews. The previews expanded into full photos, videos and posts. The remaining links underneath came to resemble vestigial metadata. This was easy to notice from the outside, from the perspective of, say, a publisher, for whom change was reflected in referrals and traffic. For users, the change happened gradually and subtly, over the course of a million consecutive pulls to refresh.

This tendency toward richer feeds was driven by the metrics with which platforms openly define success: engagement time, interactions, etc. Presented with the split-second option of viewing or sharing something fast and in-feed or slower and off-feed, users predictably prefer the former — the one that feels more like it was part of the app they were using.

And so the terms of inter-platform competition changed. Back in 2012 and 2013, a nascent territorialism played out quietly, through emails sent to reporters imploring them to cover Instagram’s presence at the Oscars, or the best tweets from Super Bowl. Platforms competed at a distance with a new feature here, a complimentary app there. But without a big wide web in the middle, the comparisons become stark and immediate, and more obvious to anyone who’s looking. So it makes a little bit of sense that Twitter would like you to know that, for all Facebook has, it didn’t have the Kanye fight. Instagram didn’t have it. Snapchat didn’t either. He chose them.

Facebook and Twitter first grew on the web but exploded on smartphones, their endless scrolling feeds positioned fortuitously for touchscreens. Snapchat, Instagram and Vine, which grew later, were designed first with phones in mind. On those services, activity is fueled exclusively by things people are typing, shooting or recording themselves. They owe very little to the web, in both senses of the word; likewise, no other party can claim much of a hand in their growth, except perhaps the mobile operating systems on which they run, or the companies that own them. The common material people consume and talk about on Instagram and Snapchat — its widely shared media — originates there.

While the platforms born on the web are gradually replacing outside media with media created within their walls, the services born as apps are attempting to create, or foster the creation of, a professional media within theirs. In doing so, the largest platforms of both origins are developing interesting commonalities: Facebook hosts most media types, as does Twitter. Instagram captions are long enough for personal posts or news stories below its photos and videos, and its chat function provides a new context in which to share them. Snapchat, with Discover, is attempting to host a popular media in miniature, and recently added the ability to share it with other users.

Each platform, in other words, seems to be setting itself up for self-sustenance. But each faces a slightly different task. Snapchat wants to terraform itself from a communications app into a functioning and complex media ecosystem. Instagram has editors curating events and hashtags into media objects that users can’t make themselves. Facebook wants to broadly remake the internet to better serve four of the largest groups of users ever accumulated, eliminating the waste and redundancy produced by interaction with an unwieldy parallel infrastructure that it can’t control. Twitter is doing lots of things, but mostly wants to continue to exist, please. Thanks!

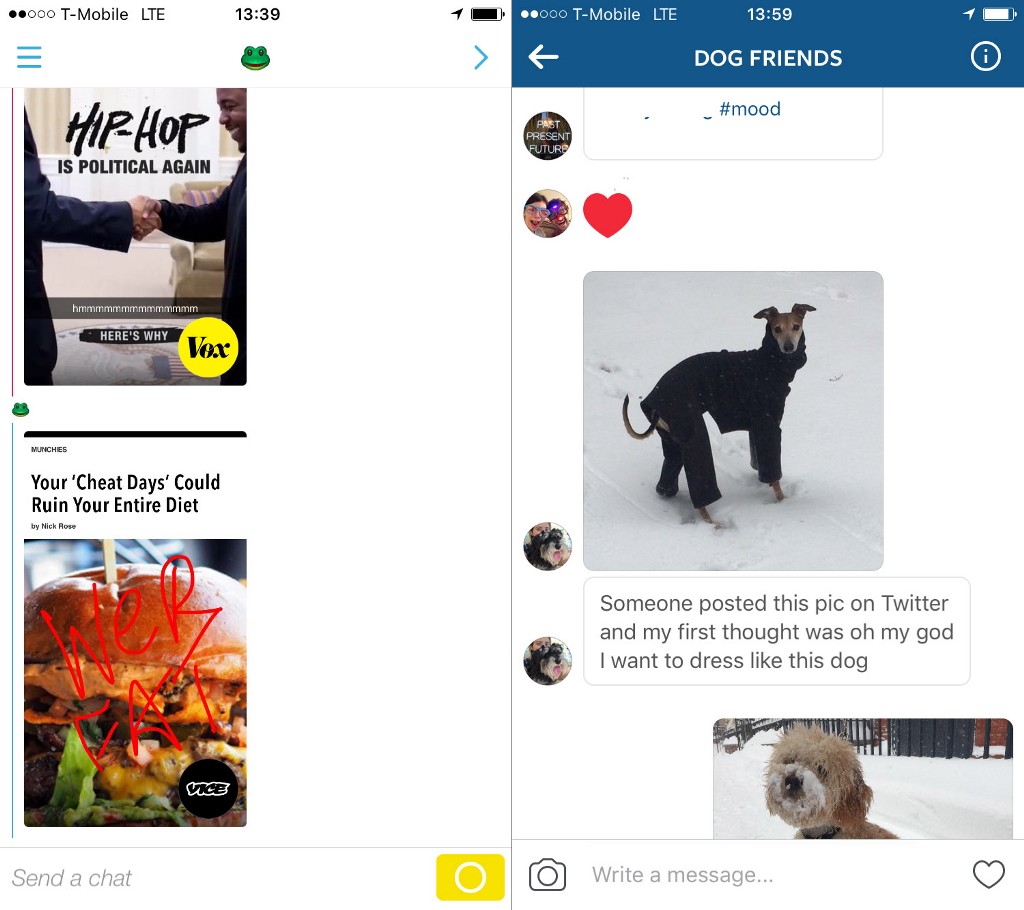

In early January, DJ Khaled, whose weird and wildly entertaining Snapchat presence has attracted millions of followers in a matter of months, visited Snapchat’s headquarters to meet with founder Evan Spiegel. Here is a photo of the meeting from Instagram.

A photo posted by DJ KHALED (@djkhaled) on Jan 12, 2016 at 4:37pm PST

This event was well-documented on Khaled’s Snapchat; I know this because I caught up on his posts through the various YouTube and Instagram accounts that archive and repost his posts constantly, accumulating hundreds of thousands of views on their own. Such videos are frequently captioned with copy-and-paste definitions of “fair use” or variations of the phrase “No Copyright Intended.”

A couple weeks after his visit to Snapchat HQ, Khaled anchored the official Snapchat Discover channel for Fusion, one of a small group of companies allowed to publish more than just snaps into the app. Here’s a sample day, again hosted on YouTube, which is owned by Google, which is one of a few companies that failed to buy Snapchat in 2013:

A lot of people watched this, probably. Publishers don’t talk too much about their Discover numbers; those who are given access to the limited metrics that Snapchat provides sign NDAs. Limited space and a constant fear of ejection keep Discover parters from talking too much amongst themselves, since they’re competing not just for audience but for the right to exist. But Discover, to the extent partners say anything about it, is reportedly big: Cosmo claims its channel is visited by three million people a day; late last year, BuzzFeed said Snapchat accounted for about a fifth of its monthly content views (roughly a billion).

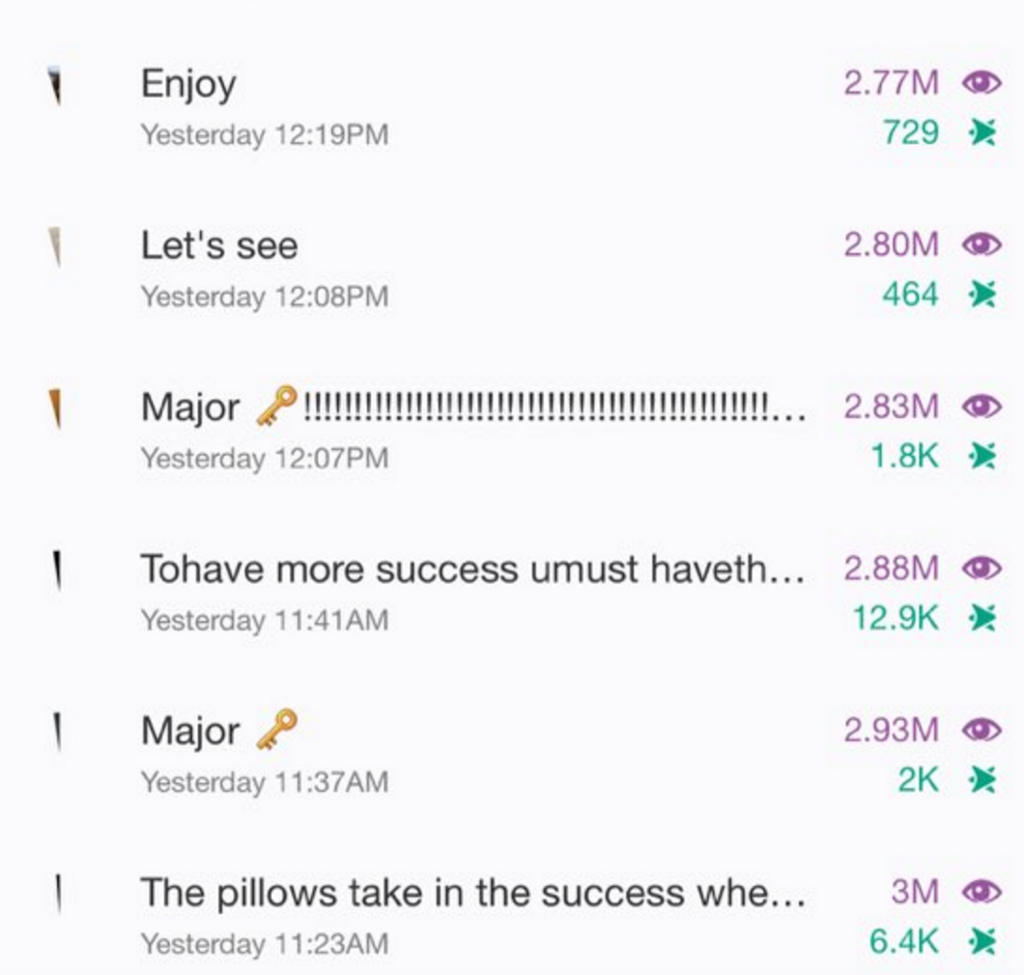

But Khaled’s own account is almost certainly more popular than Fusion’s Discover page. He posted a screenshot of his stats in December:

The ways this comparison is imperfect mostly favor Khaled. His views come from subscribers. Fusion’s, mostly, come from Discover browsers. He’s one famous person with a a little bit of help posting mostly videos of himself; they’re a staff of multiple people publishing media under an unfamiliar brand that was until recently backed by two separate old media conglomerates. In the end, maybe Fusion got some temporary exposure and goodwill. Khaled, at the very least, got some new followers.

When it first debuted, I understood Snapchat’s Discover as an awkward static attachment to a communications app. It kind of was! There was no easy way to share full stories–only screenshots–and there wasn’t much to share. But now there’s an official sharing function. Which… has been working to some extent, according to some partners? From a report in IBTimes:

For now, publishers are boasting about their Snapchat views as they follow the buzz around mobile and millennials. “On Thanksgiving, Cosmo’s Snapchat Discover channel ran videos of shirtless guys with pies. The videos generated 442,456 shares in one day,” Troy Young wrote in the end-of-year email for Hearst Magazines Digital Media.

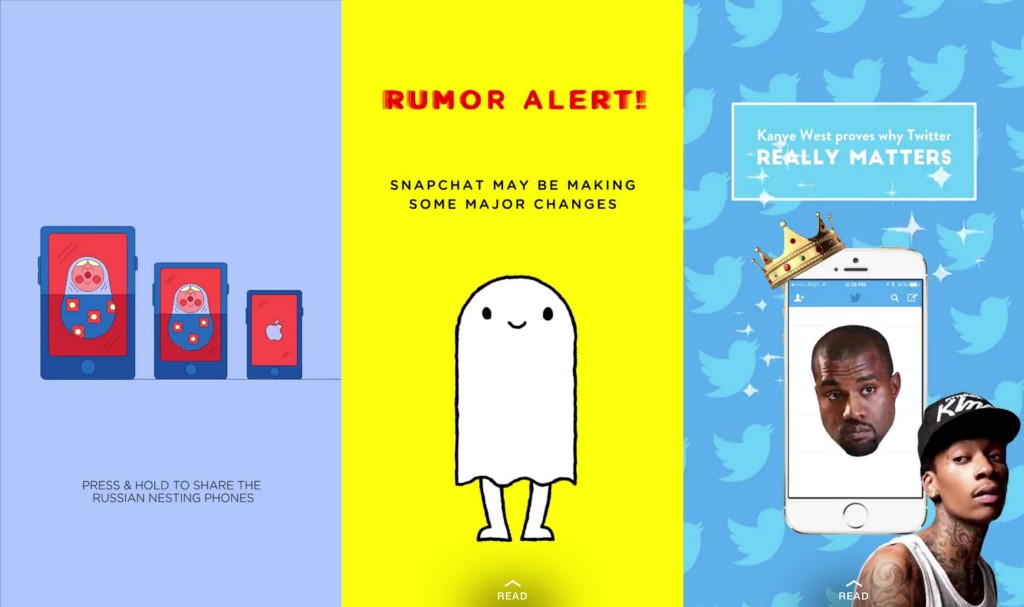

Partners are both figuring out what works and figuring out what it is they’re supposed to be figuring out. Are they optimizing for shares now? Are they optimizing for views inside the Discover tab? They’re as much trying to understand what Snapchat wants out of them as they are what their users want, and the uncertainty shows. Here, from the Mashable channel, are a few recent examples of Discover posts:

Does this actual call to share work on Snapchat? Maybe. How about this article about Snapchat? Worth a shot! Maybe a Twitter thinkpiece? It was already written anyway.

Watch Discover and you’ll see new little trends almost every week. Vox launched with a novel strategy for its channel, parceling out a single story presented over a number of slides (HELL-TREND HELL-PIECE: SNAPCHAT, TWITTER MOMENTS AND THE TRIUMPHANT RETURN OF THE SLIDESHOW). Cosmopolitan’s channel is held up as a success, but it’s more of a grab bag of jokes and lists and polls and videos than a coherent single object. The Vox slideshow is a smart use of space, perhaps better suited to viewing than sharing. BuzzFeed’s, which is full of “share ifs” and animations, seems focused much more on the latter. In any case, their relative successes are a matter of gossip and conspiracy and magic and supposition — for everyone except Snapchat.

Discover partners are given the impression, by Snapchat and by the limited metrics Snapchat shows them, that they’ve been granted special access to a huge resource — exclusive contracts to mine untold reserves of particularly valuable human teen attention. In the core Snapchat product, advertising feels intrusive. Discover creates a controlled space around advertising, and diverts some of its hundreds of millions of users to see it. Snapchat has accumulated an abundance of people and attention; Snapchat has a monopoly over advertising to its users; Snapchat devised, in addition to selling ads against its own Stories, an advertising product that doesn’t interfere with its service; Snapchat needed something against which to sell those ads; Snapchat used its audience, which exists only on Snapchat, to convince partners to fill its fresh expensive void.

It’s fascinating! And poses so many questions. For example: If partners remain limited, sort of like TV networks, will they make enough compelling stuff not to become The Boring Tab? If partners are expanded, does their share of audience remain large and lucrative enough to justify the full time staffers that run these channels? Does it become a huge marketplace like YouTube, attracting unexpected new talent who will create unexpected new forms? If Discover content becomes something primarily consumed by Snapchatters due to sharing of individual items, not views within the slideshow-style channels with obvious places to put ads, then where do the ads end up? Wasn’t that the whole point? And where does Snapchat’s participation start and stop? Snapchat had a channel, then closed it, and now has political reporter Pete Hamby anchoring politics coverage that appears on users’ homescreens whenever and wherever Snapchat pleases.

In contrast to the advertising-oriented, awkwardly placed Discover, on which a dozen-plus partners of varying levels of savvy are duking it out in the fog, the burgeoning informal economy of Snapchat fame is a natural fit for its host. It’s everything Discover would like to be: huge, fast-moving, weird, compelling. People don’t need to be shown to it, they seek it out. Behind-the-scenes posts from already-famous sports stars and celebrities, casual updates from stars of other platforms — this is the stuff people feel the need to repost on YouTube and Twitter and Instagram. This is what people on Snapchat are actually looking for.

In creating a professional media in miniature and throwing it in its own separate tab, Snapchat has managed to replicate a set of familiar platform-publisher tensions within its own company. Publishers get lots of traffic from Facebook, until they don’t, or they become a new type of partner, at which point their contribution to the whole system seems somewhat diminished; the Discover tab catches radiant heat from Snapchat’s core product until it doesn’t, or until its terms change, or until Snapchat decides that, actually, sharing is the most important metric, and, damn, sorry, some of this stuff just isn’t working for us, and, actually, we’re thinking about a more seamless way to string all this together? Thanks for your help! If Discover remains successful as an awkward appendage, it can skim money from ads and perhaps even charge partners for entry (I mean, do we know this isn’t already happening?). Or, if Snapchat keeps inching Discover further into its core product, and further away from its beginnings as an inert outside set of channels, what do its ideal partners look like? Are they more like celebrities and less like publications, or channels? Would talent contracts make sense, then? It’s easy to imagine on Vine, which purchased Niche, “a provider of software, community and monetization services for the growing creative community,” which functioned effectively as a talent agency, last year. Sure: DJ Khaled exclusive to Snapchat, coming 2017! Dan Bilzerian firing guns at Real Dolls, only on Instagram.

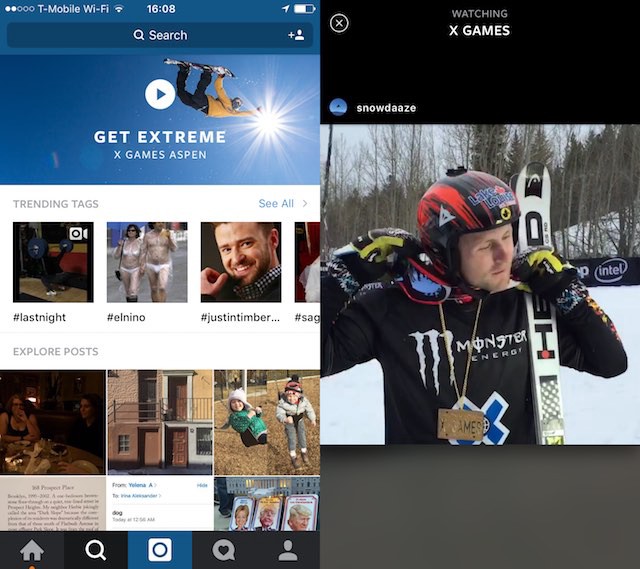

Here are some screenshots of Instagram’s coverage of the X Games in Aspen:

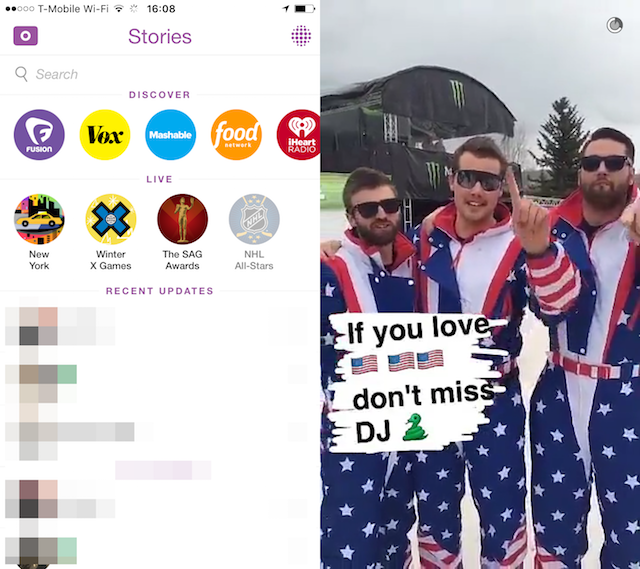

Here are some screenshots of Snapchat’s coverage of the X Games in Aspen:

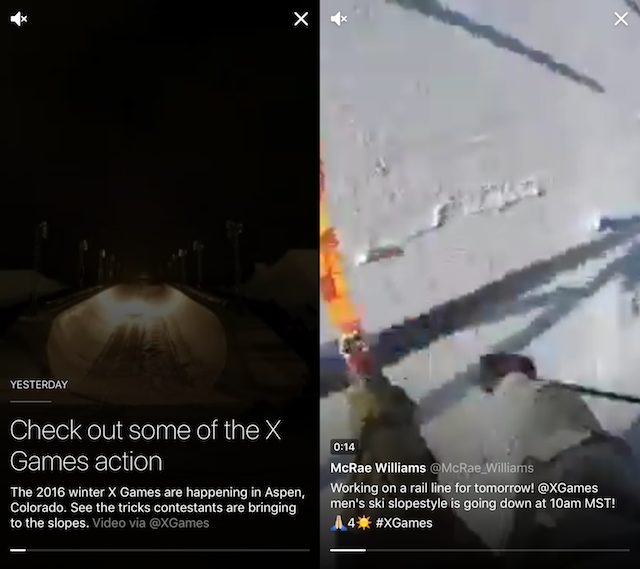

Here are some screenshots of Twitter’s coverage of the X Games in Aspen:

This is not three platforms linking out to stories of videos about the X Games, or three platforms offering commentary around a TV event. This is three platforms showing off what’s theirs: the things people are compelled, for one reason or another, to share. These overlapping stories will happen more and more often. And they’re instructive… somehow? Probably? Twitter’s feels sort of thin; Instagram’s feels better, but sort of boring; Snapchat’s feels most intimate. All are incoherent — the X Games, which spreads moderately famous people across numerous events, might not be the best demonstration of a platform’s muscle.

These types of stories, which are arranged and published by the platforms themselves (except in cases where Twitter lets a limited number of partners make Moments), serve mostly to show off what’s there to start — they’re showcases of what each platform’s users are already supplying with no extraordinary incentives. They emphasize each platform’s strengths: Instagram’s ubiquity among public figures; Twitter’s utility for straightforward deliberate communication; Snapchat’s immediacy and raw aesthetic. They also hint at what’s left for potential partners to figure out: Twitter doesn’t feel like it takes you behind the scenes; Instagram feels extremely guarded and deliberate; Snapchat excels at creating the feeling of presence but its use as a storytelling tool is not very well developed or understood.

For the self-sustaining platform, these translate as a series of questions. What aren’t we getting already, and what do we need? What goes pro, what doesn’t? How do we pay, if we do? What kind of marketplace do we set up; how much do we participate in it?

So far, we have a few early answers. Facebook lets anyone post text, photos or videos. It lets some others post articles, which can contain ads. As for who gets to make money from videos, which it says will soon make up a majority of visible content on the site, that’s still up in the air. If it’s anything like Instant Articles — a much smaller project that might not tell us much, honestly, about the direction of a much more important product — then the partnerships might be limited. If it’s a big open marketplace with generous revenue sharing, like YouTube, then it could develop into a media culture unto itself, as YouTube did. (Recall, also, that YouTube invited a large slate of premium partners — incentivized with multi-million dollar contracts — to make shows in 2011. Not entirely unlike the first round of Discover participants! How many of those worked out?)

Twitter lets anyone post text, photos or videos; how partners are supposed to make money after longer tweets or the expansion of Moments into a content type available to more partners is, perhaps, not question Twitter is worried about at this point. That’s not to say Moments isn’t conceptually interesting! It can really work, in its weird way.

This emergent genre of ⚡ moment is lovely, & it just might be how stories are ~supposed~ to be told on phone screens https://t.co/IE3Aff0lgf

— Robin Sloan (@robinsloan) January 14, 2016

(Twitter also just introduced a way to view entire conversation threads in a pop-up. Which, if you were to, say, thread 20 tweets together into a single story, are a little bit like DIY Moments. With plenty of space for ads!)

Snapchat lets anyone post limited text, photos and videos, and lets partners post more text, images and videos in a place everyone can — is persuaded — to see. Instagram lets people post photos, videos and text, and curates stories itself. But, for now, it courts partners with promises of audience and reach, not money. It’s taking that part slowly; it’s possible that it doesn’t need to bother with it at all.

At core, each social platform can be described as the same type of business: a multi-sided marketplace between advertisers and users. Andrei Hagiu, who has published extensively on the economics of multi-sided platforms, characterized them as such in 2013:

On multi-sided platforms like Facebook — and Amazon, Apple, Google, Twitter, etc. — value is created through the interactions between affiliated users, developers, and advertisers.

Facebook and these other companies want to control API access and critical user information because it’s that data which unlocks monetization opportunities.

To the extent that the major platforms make money, they mostly do it through selling ads against their users. They have gathered large networks of people, who are present largely for each other. Access to those users is valuable to people who want to sell them things, and the platform controls that access. If the business model remains more or less this, the value of an outside media company is limited to its ability to improve one of a small set of circumstances for the platform. If its participation gets more people to use the platform, that’s great. If its participation creates more of whatever specific thing it is the platform’s ad products depend on — views, time engaged — that’s great too. There are other reasons for platforms to court partners like.. idk. Completeness? Seeming Very Premium. Not Knowing Who To Invite So Inviting The People And Companies You Know Already! But none are as clear as helping the platform make money or inflate metrics in a measurable way. The biggest YouTubers, for example, serve this function, and are paid approximately half of the revenue Google collects from their work.

Facebook’s first revenue sharing product for video wasn’t a traditional form of video ad, but ads buried in recommended videos placed near videos. It was an incremental experiment. A few months after that, on an earnings call, Zuckerberg said, “there’s a certain class of content which is only going to come onto Facebook if there’s a good way to compensate content owners for that.” This suggests ad products catered, perhaps, to longer videos; one could make the argument that shorter videos, which are meant to be viewed within the regular News Feed, are already as monetized as they need to be, from Facebook’s point of view — they’re already sandwiched between ads. Does this “certain class” look like YouTube’s vast band of gradually professionalizing amateurs? Or does it look more like the TV-quality shows and films that are now inspiring bidding wars between Netflix, Hulu, HBO and Amazon? Facebook’s default answer seems to be “all of the above.”

Understood from perspective of the web, the last five years have represented a sort of tragedy of the commons. The platforms grew big and strong. Websites and publishers catered to the needs of those platforms, vague worries about control and identity set aside for the necessary pursuit of audience in an unpredictable environment. Nobody did anything wrong, exactly, and it’s not clear what they should have done differently. Some publications that functioned well under the referral regime will struggle under platforms. Others might succeed, more might materialize out of the Venture Ether. Yet others will chase new things, and many more will just continue to try everything.

Google’s Accelerated Mobile Pages are described by the company as a way to repair an ailing “open mobile web,” and have a few people convinced they can turn back the tide — or, at least, preclude some new proprietary formats, preserving a standards-guided shared resource, albeit under the guidance of Google. They load fast, and their ads are unobtrusive. And here’s how they show up in Search:

An AMP search shows you: The Google header, some informational card generated by Google, then a carousel of AMP pages. All that I’ve checked, presumably due to the limits imposed by AMP, have no page navigation to other parts of the publisher’s site. A few contained related links deep in a footer. This is an obviously faster experience for Google searchers. It also has the effect of making the result links below the AMP links seem either second rate or, perhaps, like an archive. AMP is, especially on phones, a refuge for a platform-adjacent web. But even Google’s best attempt at salvaging the consumer web involves dead-ending sites. It’s as clear a sign as any that any promising future for the web involves something like starting over. And why can’t it? The platforms are powerful relative to what came before them. But most of them aren’t truly ubiquitous, especially outside of the United States. There are a lot of internets already, and plenty yet to come.

Facebook, for example, isn’t without a context of its own. It may have a billion and a half users, but 80% of the money it makes from them comes through mobile platforms owned by Google and Apple (which serve data through telecoms). There is an appealingly neat future narrative in which Apple and Google reverse-engineer the feeds and messages of all the apps their platforms support through their respective notification trays, lock screens and wristwatches. And it’s fun to think about: What if notifications became themselves, I don’t know, sharable objects? Links in the Facebook News Feed gradually accumulated mass until they became post unto themselves; a notification in Android, the thinking goes, could absorb most, or all, of the utility contained in the app it’s supposed to link you to. And… sure? Apple and Google have not had much luck with major social platforms but maybe their leverage in this situation is real. They could try to use it.

I think subtler means of control are more important here. Have you noticed more links from social feeds leading you directly to apps? Follow a link from Twitter and it will open your New York Times app; open a Medium post from a feed and, if you downloaded the app, you’ll bypass the website. Tap an ad on Instagram and it might take you directly to the App Store. The middle ground between services now isn’t the web and its standardized links, it’s Android and iOS and their own internal deep-linking standards. It just recently became possible, for example, to travel directly into a Snapchat channel from Twitter and Facebook.

But this type of relationship requires cooperation, too. Open an Instagram link in the Twitter app, and it opens the mobile site. Only after you tap again, on “Open in app,” do you switch over. This is exactly the kind of codependency that the platforms are consciously moving away from, so I’d hesitate to assume that’s where things are headed. I don’t expect to see Twitter Moments embedded in the News Feed, or Snapchat Discover stories reproduced in WhatsApp. The way these links are deployed and denied, at least, is worth watching. As is any vigilance about unauthorized reposting, which — search YouTube for [INTERNET CELEBRITY NAME] and SNAPCHAT or VINE and see what comes up — is having quite the moment. Here’s an Instagram account called “Kylie Jenner Snapchats” with over 350,000 followers; here’s a 25-minute compilation of 6-second Vines from Brittany Furlan hosted on YouTube. 7.4 million views.

Anyway: The types of collaborations that currently function best on platforms are not really collaborations at all. Twitter Moments look great linked in a Twitter feed, and Vines embed nicely, and Periscope streams (strikingly!) play in the feed, but Twitter owns Vine and Periscope. Discover stories share seamlessly in Snapchat’s chat function, because why wouldn’t they?

And so we arrive back at [SPINS WHEEL] Facebook? Again? [SPINS REVOLVER CYLINDER] Haha, hm. Well, ok: You know where Instagram posts look just fine? In the Facebook News Feed, where they are expanded to full size. Facebook videos share pretty nicely to Facebook Messenger. Facebook tested a “share to WhatsApp” button in the Facebook app a couple months ago. To a messaging app, Facebook is the outside world. One layer up, Facebook is experimenting with its own notifications system. One further, the company is running tests to see how it would manage if its apps got removed from Google’s Android Store. A layer above that, the company is partnering with mobile carriers in developing countries to provide free access to Facebook. A layer above that, Facebook is developing the technology to — again, at first, in the developing world — to become an ISP. Sheryl Sandberg, Facebook’s COO, used a familiar-sounding phrase on the company’s first earnings call of 2016: Facebook, she said, was the new “town hall.”

Twitter’s Vine-Periscope-Twitter stack is comparatively short and narrow. I’m not sure quite what’s left if Twitter, still the most porous service, withdraws further from the web. It’s anyone’s guess whether Snapchat can build Discover into a serious set of channels and publishers, or into a market-like platform that would give its users a glut of media to snap about. But a Facebook News Feed that produces articles and videos and photos exists within a larger ecosystem that its parent company owns. The theoretical Discover-post sharer is, simultaneously, a Snapchat user, a Snapchat Discover reader, and a Snapchat text chatter. The Facebook sharer is just a Facebook user. Maybe a Messenger user. Or maybe uses WhatsApp, which, it so happens, has aspirations on the platform level and well beyond (2016 will be a year in which lots of app humans repeat the phrase “conversational media”).

As a service, Facebook proper might strain to do and be everything. It might not convince Kanye, or Khaled. But maybe it doesn’t need to. That’s what vertical integration is for.

Gifs cut from this video courtesy of Okayama University and the Tokyo Institute of Technology. NO COPYRIGHT INTENDED!!!!

Vagabond Express

by Haley Cullingham

“I wondered what she did,” Alice Adams wrote of a fellow Greyhound passenger in the New Yorker in 1981, “what job took her from Oakland to Vallejo.” Adams had gotten on the wrong bus. She was on her way home to San Francisco from Sacramento, and instead of boarding the commuter coach, she got on the milk route instead; the woman sitting near her represented a parallel universe traveling the same line. Post-divorce, Adams was especially susceptible to this kind of imagining. Who was this woman? And what fine lines, drawn of coincidence and choice and culture, separated Adams from her?

The day after she accidentally took the slow bus home, Adams travelled to work next to a woman who boarded at the same station she did, disembarked at Adams’s destination, and went to work in a building right beside her office. She found this duality unsettling. On every bus we don’t board, a possible life drives away without us, and the romance is ruined if the possibility presented is as mundane as our own reality. Better instead, Adams decides, to wile away commuter hours contemplating individuals like the woman working in Vallejo, fellow travellers who were different: a handsome black man, a heavyset woman, someone in a sharp purple suit who says what other passengers are afraid to. At the end of the piece, Adams writes of her trips on the Greyhound, “I could meet anyone at all.”

The years following the financial crash were a good time to meet people on the Greyhound. Mother Jones reported that in 2008, intercity bus travel went up almost ten percent. In the years that bracketed the recession, I did a lot of disappearing on Greyhound buses. Lacking the wherewithal to determine what my life should look like, I worked a couple of jobs and saved up money and then spent it rumbling from coast to coast at semi-regular intervals, visiting friends, or helping them move. I was not riding for a purpose, particularly, but because motion gives shape to purposelessness.

The long-haul nature of the rides meant that there was a lot of time to kill from Michigan to Tennessee to Kentucky, Texas to New Mexico to LA. When you’re waiting, people tend to sidle up to you and tell you something about why they find themselves on the bus. Prior to 2008, almost everyone I spoke to was travelling to visit their children. An older man carrying a fold-up stroller pointed me to the best delis within safe walking distance in Buffalo; an eighteen-year-old who boarded the bus in Kentucky shared his fleece blanket with me, grinning as he told me that his best friend from back home in California was pregnant, and it was his, and he was going to help out, even though her boyfriend wasn’t happy about it; a woman walked over at a station in Kansas, frenetic and happy, and told me she was waiting for her son, who had just come home from Iraq. But after 2008, all anyone on the buses talked about was finding work.

I met a journalist in the Denver bus station just before Christmas in 2011. He had a neatly trimmed beard and one duffel bag. He had been riding around for about six months. His sister had gotten sick, and he spent his retirement money paying doctors to try to cure her cancer. By the time she died, his money had run out. He tried to find work near home, but there was none to be had, so he decided to get moving. “My neighbour’s wife is six feet tall, so I gave them my king-sized bed,” he said. “I gave my daughter my good kitchen knives, and I got on the bus.”

There was a young man in the Salt Lake City terminal with the blondest eyelashes, bleached by the city’s anemic rising sun. He had just finished a stint in the armed forces and was heading to a training centre to learn how to drive a truck. He turned a souvenir-of-service coin that read “Proudly giving the enemy a chance to die for their country” over and over in his pale white hand. “I hope I do okay at the trucking academy,” he said. “I heard if you make one mistake they send you home.” There was an older man grinning from the space between the seats, with a diamond earring in each ear, and salt-and-pepper stubble, also headed to a training centre for drivers. He had a scruffy teddy bear with him. “This was my good luck charm the last time I was on the road in a rig,” he said. “Thirty years ago, in Michigan.” A soft voice came from beneath a black hood beside him. “Did it work?” The older man gestured to the younger one sitting beside him. “This is the kid’s first time. I’m looking out for him.” Later, the younger man would fall asleep with his hooded head on his new friend’s broad shoulder.

The Greyhound’s place in popular imagination is an intersection of practicality and myth. Why are we on the bus? Inevitably, it’s because we don’t have another option. But there’s a poetry there, too, the rhythm of endless highway. Nathan Heller quotes Rudyard Kipling in the New Yorker: “The time is near when men will receive their impressions of a new country suddenly and in plan, not slowly and in perspective.” The time Kipling predicted in 1914 has long since arrived, but those sudden impressions don’t come cheap and are far from accessible. In his piece, Heller describes another predicted shift: the change from physical travel to virtual experience. He writes that this coming transition is “about ways of knowing.” Contrasted against VR, bus travel, even more than air travel, seems clunky, lumbering, endangered. But it’s at that intersection of practicality and myth, of no other option and “ways of knowing,” that we find the best reason to be on a Greyhound bus.

National upheaval has always been good for the bus business — when people are on the move for work, Greyhound and the many smaller lines it gobbled up in the mid-twentieth century have historically been the most affordable way to get to wherever they’re going. “The recession of the early 1980s worked to the advantage of Greyhound,” wrote Brenton M. Barr and Peter John Smith in their 1984 book Environment and the Economy: Essays on the Human Geography of Alberta. That same province, and the mountains and prairies surrounding it, would see a similar resurgence in bus travel when the North American economy crashed again. “Where communities are widely scattered but jobs are concentrated in select areas,” wrote Josh Wingrove of the Canadian Prairies that year, “Greyhound is a commuter utility.”

Greyhound has its roots serving commuters like Adams and the workers in the prairies — getting its start in 1914 as the “Snoose Line,” transporting miners to and from work in Northern Minnesota for fifteen cents a ride — and that legacy has persisted into the new century. What’s interesting is that when the country struggles, Greyhound succeeds: It is a perpetual and oft-maligned presence, a back-up plan that is not without its own poetry. Why are we on the bus? Almost always, because it’s cheaper. We take the bus when our money is so scarce it becomes worth more than our time and as a result, the nature of our time shifts. We take the bus when we don’t have a life to rush back to. We take the bus when we can’t afford to do anything but disappear.

Four years before Greyhound got its start moving men to the mines in 1914, the first wave of the Great Migration began. Six million African-Americans moved to industrialized northern cities over the next twenty years to leave the Jim Crow South behind, many of them on a bus; by 1920, ten years into the Great Migration, the black population of Detroit had grown six hundred and eleven percent.

After the Great Depression brought the first Great Migration to a halt, Greyhound still played a profound role in the lives of workers. Men travelled the country by bus as part of the Works Projects Administrations efforts to get America back on its feet. As they traversed the Mississippi Delta, they were often followed on board by blues musicians, including Robert Johnson, who knew they could count on the workers to spend good money in the bars at night. It was these trips that inspired the iconic line in Johnson’s “Me and the Devil Blues” in which the musician asks the devil to leave his body on the edge of the highway so that his “old evil spirit can catch a Greyhound bus and ride.”

Condemned spirits riding buses took on a new meaning during the Second World War as Greyhound became responsible for moving soldiers to the east and west coasts. The company didn’t miss the opportunity to market its role in the war effort, running advertisements that read, “The Army moves by Greyhound,” patriotic optimism harnessed to keep the war effort moving. The second, and much larger, Great Migration was also motivated by defense jobs and a desire for freedom from racial segregation. From 1941–1970, another five million African-Americans would leave the South, many of them skilled workers seeking employment in urban center Greyhound was again the ticket out for many.

The company’s place in civil rights is a complex one. Read a little, and you’ll find the bus line portrayed as a symbol of freedom: Civil rights protestors took the bus south in an historic journey protesting segregation. In 1961, one of two groups of original Freedom Riders made their way south from Washington on a Greyhound bus. The protests were plagued by violent racist attacks. In Alabama, someone threw a bomb onto the bus. The passengers were able to escape unharmed, and photographs of the burning vehicle made front-page news across the country. The Freedom Riders were ultimately successful, and Greyhound has a symbolic role in that story.

But read more, and the picture becomes less bright: The company, which ran buses with curtains separating passengers by race into segregated terminals along lines in the south, was a potent symbol of the racial divides on each side of the Mason Dixon line. Following the violence, no driver would get behind the wheel to carry the protestors to their final stop in New Orleans.

“On the one hand, Greyhound had a history of hiring blacks,” Gary Belsky writes in “100 Years of a Dirty Dog,” his excellent piece on the company for Mental Floss. “On the other hand, most of those jobs were menial. The good jobs — drivers, managers, mechanics — generally went to white men.” In 1963, as part of a campaign against discriminatory employers, the Philadelphia NAACP successfully reached an agreement with Greyhound ensuring that three black employees would be hired for jobs — telephone operation and baggage handling — that had previously been open only to white applicants. “Greyhound also pledged to hire additional black workers as jobs opened up in previously all-white occupations,” writes Matthew J. Countryman in Up South.

There’s a power in forward motion, even if, as Johnson sang, it’s taking your soul to hell. Greyhound was important in de-segregation movements much in the same way it has been important in so many moments of national change: by being the only available ride.

After years of butt-burn on days-long Greyhound rides, I can’t help but wonder why the company’s place in our cultural imagination remains secondary to the Great American Roadtrip, or the Eisenhower Interstate System. There is something here that transcends practicality. It’s one of the last spaces to access what feels like suspended time. No one expects you to call them back if you’re on a Greyhound bus. Ultimately, perhaps, the myth of the Greyhound is the myth of escape: The Greyhound is one of the last almost untracked forms of transportation. To ride the bus across the country is to realize how lonely it is, the true scale of its emptiness. It’s to realize how much it changes, when you fall asleep rolling past Christmas tree lots covered in frost in Tennessee and wake up to the smell of smoke from a taco counter in small-town Texas.

People with hours to kill on a lonely highway will inevitably turn their minds to the narrative that brought them there, and as such, Greyhound becomes a vehicle for self-mythologizing. When people speak about the lives they’ve left behind and the ones they are hoping to find somewhere new, there is a common rhythm: fireside, last call, half-naked in a dorm room; the rhythm of stories told as vividly as they are felt, of personal history portrayed as biopic. There’s a reason these tales make room for such gravity: there needs to be room, within the telling, for re-imagining. For Alice Adams, those rides between Sacramento and San Francisco allowed her the time to compare herself to her fellow passengers and, in doing so, figuring out who she would become post-divorce. The bus, then, seems like the perfect vehicle for those searching for a new life: It provides the time to figure out who you’ll be when you get there.

After all the men got off the bus to go to trucking school, I stayed onboard, heading west. As I looked out the window at the small desert towns that gather at the foot of California, I saw a sign pointing down a dusty strip of main-street-somewhere. Wooden, weather-stripped, and, written in black paint: COWBOY POETRY.

Photos by Ethan, Eva, and Omar Bárcena, respectively

Thomas Ragsdale, "Time To Go"

Even if you are, as am I, a staunch defender of the classic rotation of seasons — the promise of spring, the seduction of summer, the crispness of fall and the grim determination of winter — you can still probably find some amusement in what appears to be our new Mystery Mix order of weather wherein one day it’s May and the next it’s November. So we woke up to winter today. What will it be tomorrow? NO ONE KNOWS. There might be a heatwave next week, and everyone will just shake their heads and say, “Yeah, that’s what happens here in February.” It is indeed a remarkable age in which we live. Anyway, there’s some backstory to this track but you do not need to know it to enjoy, so figure out how much reading you’d like to do in advance and then enjoy. [Via]

New York City, February 3, 2016

★ The morning was so dark that the mirrored tower was failing at mirroring. It had rained already. The last snowbanks on the cross street were eroded and diminished. At midday, umbrellas were out and shiny with new rain. It seemed as if it must be cold in the gloom, but it wasn’t. It got wetter and wetter; deep flood puddles formed at crosswalks. Raindrops fringed the hood of the waterproof jacket, to be shaken away with a sharp head nod. The four-year-old let go of his umbrella and let the adult holding and guiding it by the ferrule keep walking ahead. The stairs up out of the subway into the soggy dimness felt as if they were leading downward. A vendor knocked water out of a greenmarket canopy and it hit the pavement with almost the sound of breaking glass.

All the News That's Affordable to Print

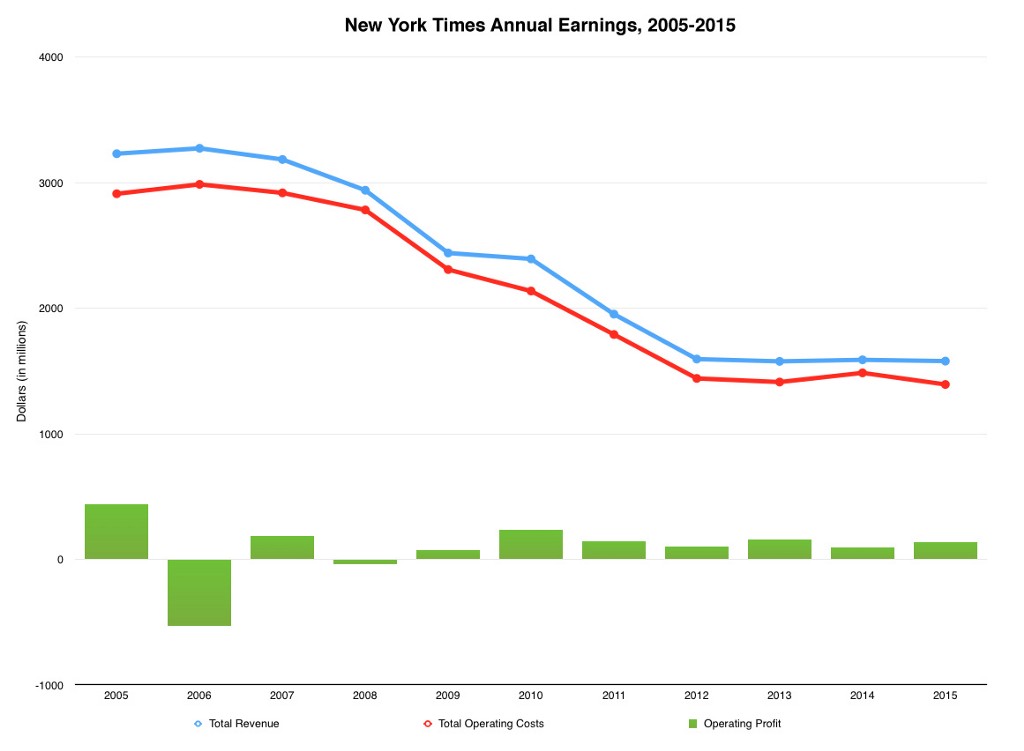

Good news, the New York Times had a higher profit in 2015 than it did in 2014. That extra profit did not come from an increase in revenue as digital finally offset the momentous decline in print — how great would that be??? — but from the Times’ now-longstanding source of profit-making: cutting costs faster than revenue falls. Here’s a chart of the last ten years of Times annual revenues against total operating costs and operating profits:

Even with lofty goals like $800 million in digital revenue by 2020, the Times is already preparing the newsroom for more severe cuts, with the announcement of a top-to-bottom sweep of the newsroom in search of “further areas for cost reductions,” led by executive editor Dean Baquet and Upshot editor David Leonhardt:

“The simple fact is that to secure economic success and the viability of our journalism in the long term, the company has to look for judicious savings everywhere, and that includes the newsroom,” Mr. Baquet said. … “Instead of cuts and additions without a clear picture of where we are headed, we want to approach the task thoughtfully, with our mission and values clearly in mind. Everything we do must either be part of that mission or help generate the revenue to sustain our journalistic dominance.”

(Here’s a link to the full memo, in which Baquet also says, “time to catch our breath and come up with a shared vision for what our report, and ultimately the New York Times newsroom, should look like in the coming years.”) Between this and Conde Nast and Hearst spinning off their print services into an easily disposable joint venture, sounds like 2016 is off to a great start for print media!!!

Photo by Jessica Sheridan

A Poem by Martha Silano

by Mark Bibbins, Editor

Proverbs

Who knows best a pineapple’s heart? A knife.

Words are good, but fowls lay eggs.

A hungry stomach makes a short prayer.

The first may become the last.

Words are good, but fowls lay eggs

till the moon disappears completely.

The first may become the last.

Little by little grow the bananas.

Till the moon disappears completely,

a new moon cannot rise.

Little by little grow the bananas.

A woman is beautiful until she speaks.

A new moon cannot rise

while a hot needle burns the thread.

A woman is beautiful until she speaks.

If you know what hurts you, you know what hurts me.

While a hot needle burns the thread,

a good buttock finds its own bench.

If you know what hurts you, you know what hurts me.

A bad workman quarrels with his tools.

A good buttock finds its own bench.

Not even a bell rings the same way twice.

A bad workman quarrels with his tools.

The eyes close in sleep, but the pillow lies awake.

Not even a bell rings the same way twice.

The tongue has no bones yet breaks its skull.

The eyes close in sleep, but the pillow lies awake.

After we fry the fat, we’ll see what’s left.

The tongue has no bones yet breaks its skull.

A hungry stomach makes a short prayer.

After we fry the fat, we’ll see what’s left.

Who knows best a pineapple’s heart? A knife.

Martha Silano’s books include Reckless Lovely, The Little Office of the Immaculate Conception, Blue Positive, and, with Kelli Russell Agodon, The Daily Poet: Day-By-Day Prompts for Your Writing Practice. She edits Crab Creek Review and teaches at Bellevue College.

You will find more poems here. You may contact the editor at poems@theawl.com.

Sofie Winterson, "KIDS"

2015 sucked, but Sofie Winterson’s “I Only Wanted You” was an undeniable bright spot. Based on early returns it looks like 2016 is going to suck even worse, so at least we’ve still got Sofie Winterson stopping by with tiny delights such as this to help us through, for whatever that’s worth. Given what we’re looking at for the rest of this year it is going to have to be worth a lot, I think. Enjoy.