Berned in Reno

Last Thursday I found out Bernie Sanders was going to speak in Reno on Friday. I don’t live in Nevada, but I live in a small California town called Nevada City, which is in Nevada County, so I spend a lot of time explaining to people that I don’t live in Nevada.

I texted my friend Hannah, who is twenty-seven and tiny and beautiful as a daffodil. “Bernie in Reno tomorrow!”

She texted back two hearts and five flames and “BERNIE BERNIE BERNIE.”

On the drive, Hannah and I tried to figure out, between Rihanna and Beyoncé, who was Bernie Sanders and who was Hillary Clinton. Beyoncé’s music was maybe more Sanders-y, because it was braver, and more personal, and Rihanna was more slick. But in some ways, Rihanna seemed like a more Sanders-y sort of person. “I think Beyoncé is super talented and beautiful and amazing but it sometimes it’s annoying how she’s like ‘I’m married, I’m Christian, I’m good,’ even though she’s also, obviously, more than that. I really appreciate how Rihanna is like, kind of a loose cannon stoner.”

“I thought you hated pot,” Hannah said.

“I do,” I said. “But I like people who feel like they have to smoke it a lot.”

I told Hannah the woman who was currently sitting in her seat at our co-working space (she had to move downstairs, long story) has told me she thought 9/11 was an inside job.

“What did you say?” Hannah asked.

“I started yelling at her.”

“How did she respond?”

“I have no idea,” I said. “Indignant rage always ends up being kind of a solitary experience.”

The Bernie Rally was in Sparks, just east of Reno, at the Nugget Casino. The moment it came into view we started to chant: “Bernie, Bernie, Bernie. Bernie!” We parked easily in a giant structure and got out of the car, then jumped up and down and shouted “Bernie!” some more.

There were maybe fifteen people standing at the casino entrance. “Is this the Bernie line?” we asked a security guard.

“Yes,” he said. “You’re here early.”

“We’re going to be so close to Bernie!” Hannah said. She put on some lipstick. “I have to look good for Bernie!”

“Oh yes,” I said. “I know how you millennial women are at your Bernie rallies.”

Some guy came up with shitty homemade Bernie buttons. Hannah got one that was covered with rainbows; mine just said “BERNIE,” with a blurry picture of his smiling face.

“Yours is boring,” Hannah said.

“Yours looks like a logo for organic marijuana fertilizer,” I said.

We talked to each other for a few minutes but then, tacitly acknowledging the only way to wait for Bernie was by making Bernie Buddies, struck up a conversation with the people in front of us. Rebecca and Aria were first year students at University of Nevada at Reno. “I’m actually on the fence,” Rebecca said. She loved to talk and she loved to listen and I was sure she was destined for success in a career where she would actually help people. “My dad is a Trump supporter. He thinks I am going to hell.” She seemed pleased about this. “My mother thought she was but I made her take one of those tests, and she found out she’s like, seventy-three percent liberal.”

Aria had enormous eyes and was wearing a romper and maybe colored contacts. Her parents were from Mexico, and not terribly political. She was full-on Bernie.

“That’s what we are,” Hannah said. “We’re full-on Bernie.”

Aria nodded and gave a thumbs up. Her fingernails were Tiffany blue. “I thought I was a Republican until Rebecca made me take that test,” she said. “Then I found out I was a Bernie supporter.” She said this as if she were talking about her blood type. “I just always thought I was Republican because I was pro-life, but then a friend of mine explained to me that women would get abortions even if they weren’t legal, and die. So I changed my mind.”

I asked her when this all happened. “I guess a few weeks ago?” she said. She shrugged and her romper slipped off her shoulder a little bit and as she tugged it back into place with a slightly apologetic smile I felt like could see her innocent heart under her romper. Hormonal tears flooded my eyes.

Rebecca had more to say. She liked Bernie a lot, but she really wanted to see a woman president. She also didn’t know if Bernie had enough experience. I asked if she thought Obama was a good president. She said she did. “Well, he had way less experience than Bernie has, and he’s been pretty good,” I said.

A tall white guy walked up and stood near us, and then he got closer and closer and soon he and Rebecca were nuzzling each other like two sheep in a field. In time, we learned that he was a disappointed Rand Paul supporter with a day off from work. Every time I met his gaze I sensed he was telegraphing to me, “Stop trying to telegraph to my girlfriend that I’m not good enough for her” and I sensed he knew I was telegraphing back, “You can’t make me.”

Hannah tugged me on the arm. “This lady is undecided,” she said. “You should talk to her.” So I engaged in conversation with Angela. She was sixty-five, one of those people who is, not unattractively, all one bronzed color; tan eyes, tan face, tan hair, tan jacket. Angela watched the news all day. “ I just retired and I just watch it and make myself crazy changing my mind this way and that way.” She laughed.

I gave her my speech about how income inequality was the single biggest problem in America and how if we didn’t address that we really weren’t addressing anything, and she was very agreeable. After a long time, she finally said, “I really would just like to see a woman president.”

Does anyone remember in Laurel Canyon when Christian Bale is going off about how great and brilliant his fiancée, Kate Beckinsale, is, and Natasha McElhone, who is in love with him (as he is, arguably, with her) shrugs and asks, “Who can compete with that?” I felt like her.

Standing there, I allowed myself to think all my most uncharitable thoughts about Hillary Clinton supporters. Not the Costco-shopping Cupcake Chardonnay and Wild Horse Pinot drinkers with their enormous Pottery Barn couches who love gay weddings and get abortions but would just as soon allow half the United States to life in jail and the other half in a gated community, because I don’t really know any of those people. No, I was having uncharitable thoughts about the ones I know, my family, my friends, the people in my life I have always thought of as progressives. I hate how they lecture me that I don’t understand reality, and that I’m silly to think anyone like Bernie Sanders could be president when he doesn’t understand how to work the system they all claim to hate so much, and I hate that it is essentially quaint and precious and delusional to believe that our country could free itself from corporate interests and values, and I hate that the ugly stuff and meaningless jargon that give those ties its shape and its sound seem to be perfectly tolerable to them and finally, I hate them for saying that just because so many truly stupid backwards fucks hate Hillary Clinton, that it’s my duty to like her because I’m a Democrat, and doubly so because I am a woman, because it’s not.

The line to actually get into the ballroom at the Nugget was like airport security, but worse. Security guards weren’t just searching bags, they were searching wallets. Right in front of us, some weird Crocodile Hunter-y dude had taken off a coat with about seven thousand pockets, and they went through every single one of them. He was also carrying a knife because who knows when you might have the opportunity to skin a possum at the Nugget Casino in Sparks.

At around three o’clock, they started bringing people in to sit on a row of bleachers behind the stage. Bernie supporter Dick Van Dyke emerged. There was a buzz while all the old people explained to the young people who Dick Van Dyke was and another buzz when they didn’t understand and we explained again. Some guy named Chris with long hair who looked like a stocky Greg Allman (though really, who doesn’t?) from the Nevada for Bernie campaign stalked up to the podium, a veritable panther for the Left. He looked at us and with stocky panther gravitas demanded to know if we were ready for a revolution. We jumped up and down and said that we were. Chris was followed by Susan Sarandon, whose matching purple sweatsuit gave her the air of a rich woman alighting from a plane in Scottsdale. She spoke for about five minutes about Bernie’s general awesomeness and was followed by a fiftyish former Republican who — you guessed it! — had a serious case of the Bern.

And then, Bernie came out.

The last time I was this excited about seeing someone was The Unforgettable Fire tour. “BERNIE BERNIE BERNIE,” we all yelled, glowing with love for our candidate. When it quieted down, someone yelled, “We love you Bernie” and he grimaced, then held up his hand in a sort of enough-of-that-nonsense gesture. But then he smiled. I know it’s condescending to say that old people are cute, but Bernie is so cute. I love the electric socialism of his smile.

You already know what he said: Healthcare is a right and not a privilege, yet we are the only major country in the world where that is not true. He asked people in the audience to shout out the amount of college debt they had, and a woman next to me had $200,000 in college debt. Someone else said they were $400,000 in debt and I swear to Christ I saw a bullshit shadow pass over Bernie’s face. But then a few nights later friend told me she’d had a one-night stand with a therapist who had $400,000 in student debt. “That’s why it was a one-night stand,” she explained

Someone fainted as Bernie rattled off those income inequality statistics, so he stopped everything for a moment. Once he saw other people were taking care of it, he just sort of backed away from the podium and chilled out for a bit. “He is a composed fucking guy,” I said to Hannah, and she said, “BERNIE! BERNIE! BERNIE!”

We got a packet to go canvassing, and found a Mexican restaurant in a casino. People were staring at me and I looked down and saw that I was wearing like two hundred Berine buttons. I removed all but one. The restaurant was opulent in a casino way, with a gold touches in the paint and a recessed ceiling filled with fake roses, which I found as difficult to assess and categorize as Susan Sarandon’s outfit. Hannah announced that she’d lost several Instagram followers, possibly because she’d posted pro-Bernie stuff, and one guy she knew from college had commented negatively on her Bernie picture.

“I went to UC Santa Barbara,” she said. “I’m friends with a lot of bros.”

We ate our food like well-trained NorCalers, complaining about its quality. But when we got the bill, I said, “Holy shit, a Jameson on the rocks is only $3.50.”

“Wow,” Hannah said. “Let’s move here.”

We canvassed in a suburban area off of McCarran Blvd, in more or less the same place I knocked on doors for Obama in 2012. We had about forty doors to knock on. “I’ll just talk to people, you do paper work,” I said. She said, “This seems like a good use of everyone’s talents.”

Some people might think canvassing involves arguing with people, but it doesn’t. If they say they’re undecided, you bring up Bernie’s issues — single payer healthcare, free college tuition, income inequality — but you’re not necessarily banking on moments where people suddenly see the Bernie light. Although these moments do happen. But not to us: Our goal was to find out who was planning on caucusing for Bernie and to make them more accountable about going.

The first guy said, “Go away” and slammed the door in our faces. A few people said they loved Bernie but had to work tomorrow, and I said, “When Bernie is president no one will have to work on Saturdays,” and we had a good laugh. One woman actually embraced me. “I love Bernie,” she said. “He is so wonderful! My whole family is going to caucus for him tomorrow. We can’t wait!” She sent me off me a jar of ice water and some sort of diet iced tea thing that brews when you twist the top which Hannah and I regarded with perplexed fascination.

The Bernie headquarters were in your typical mini mall, across from a nail salon and next to some New Age establishment that screamed mail fraud. We handed in our packet and the person who took it said thanks. But there was no outpouring of gratitude. For some reason I though we might get peanut butter and cheese crackers like you do after you give blood, but there was nothing left to do except drive home.

There was a significant snowstorm between Reno and Truckee, the first town over the border in California. “Isn’t it weird that the Donner party was like, a real thing? Like they actually died here. But we just drive over, with our heaters and our snacks,” Hannah said.

I tried to somehow process the miraculousness of finding myself at this moment in history but the best I could summon was a vague acknowledgement of comfort. As we descended the snow transitioned to rain and then to fog. I said “Is it really immature of me how often I find myself thinking Hillary Clinton supporters are tools?” and Hannah told me that everyone she knows who’s voting for Clinton likes her because she was on the cover of Vogue. The part of me that’s still a Yellow Dog Democrat felt relieved.

The next day, I was in the parking lot of the ReSale Store in Grass Valley when I read that Clinton had won Nevada. Hannah wrote me a text: “We should have knocked on more doors. At least it’s Rihanna’s birthday.” She added the birthday cake emoji.

I went out for dinner and split a half bottle of Barolo and a filet mignon with a friend of mine who is a Hillary supporter. After my first half glass, I totally went off on her. She just laughed. “Maybe you’re right,” she said. “Maybe it is because I really don’t care.” And I really do, but indignant rage always ends up being kind of a solitary experience. I let her pay.

Leon Vynehall, "Kiburu's"

Very few things excite me, but “new Leon Vynehall” is on that list. Hopefully it is on your list as well. Otherwise, I don’t know what to say to you. Do you want me to lie and tell you the day’s going to be okay, even though by not liking Leon Vynehall you have sacrificed any chance for joy you might have otherwise experienced in the next 20 hours or so? Fine, I can do that. Everything’s gonna be great! Today won’t be the regular mirthless parade of quotidian misery and emptiness you normally shuffle past. It’s all gonna be much less bad than usual. Enjoy! (Did you buy that? I thought I put my all into it, so I hope you did.) [Via]

New York City, February 22, 2016

★★★★ Globs of light gleamed at irregular intervals on the shiny diagonals of the Hearst Tower, like an electrophoresis gel result. Old gray tatters of filthy plastic waved gently in the fourth-floor treetops. The food smells on the breeze were appealing. The faintest of blue hazes shimmered against the otherwise perfect clarity. High-contrast black-and-white Adidas gear marked the convergence of teens. The light was an invitation to skip the train change at Times Square and walk the extra distance crosstown. Baby gear showed its tacky spots of color inside a dull glass box. A lion’s head roared or yawned up on a cornice, its canines green against the depths of its mouth. The three silver caps atop the Empire State Building’s center columns of windows gleamed like tinfoil wrapped tightly around a sandwich.

Astronaut Endorsed

“I don’t think Hillary has horns though she does have a vagina and wouldn’t you want it sitting on the chair in the Oval Office (not to get all weird) because things will never be the same. She will see something no woman in America has ever seen before and then all of us will see it. She’s like our astronaut.”

The Deactivation of the American Worker

The American employee is increasingly no longer an employee at all.

by Carter Maness

Last November, at the offices of Gawker Media, a series of editors were summoned, one by one, via direct message on Slack, the company’s inner-office chat and collaboration platform, to a conference room. The executive managing editor wanted a word, they were told. Workers who hadn’t been messaged began to notice that the names of the summoned, ever present on their contact lists, were going dim and then disappearing from Slack. “I had no idea layoffs were coming — none of us did,” a former member of the editorial staff told me. “After I returned to my desk, my Slack account had been disabled. I guess the fear was that employees who had been let go would spread word to their coworkers. But it’s Gawker after all, a place where secrets, lies and even closed-door layoffs eventually come into the light.”

There was no official announcement, memo, or really any communication to explain what was happening until after the layoffs had been completed. The job terminations, like the bulk of the media outlet’s work, were first experienced by most Gawker employees in digital, rather than physical space. Deleting the accounts was merely the company’s attempt to assert control of its office space, and Slack’s role in the layoffs simply exemplified where work was actually being done; it also serves as an indicator of, for many employees in the coming years, where it will end.

Slack isn’t down. You’ve been fired.

— @fmanjoo

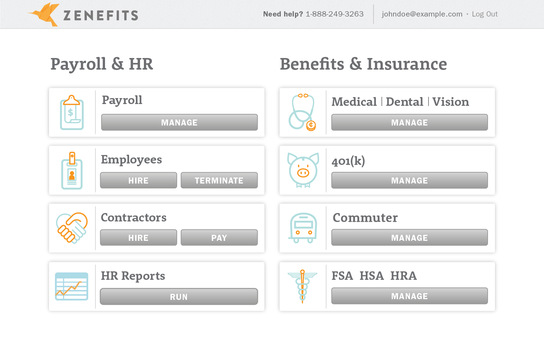

On Twitter, the deactivated Slack account became a way to demonstrate fear of being laid off. “Is my Slack down or am I fired?” is a good joke in a Freudian sense because it reveals a deeper truth about how tenuous jobs have become. Before, a worker might arrive to the office to find her keycard no longer works, or their desk contents boxed and ready, a security guard waiting to escort them back to the parking lot. It’s a messy image, bad for morale and, now, easily avoided by quietly deleting a worker’s access to their work and colleagues. As the open office, with its cacophonous lack of privacy and false promise of improved collaboration, is replaced by a virtual one running on labor and benefits platforms like Slack and Zenefits (lol), the American employee is increasingly no longer an employee at all, but someone granted the privilege to work by a network administrator, an opportunity just as easily revoked.

Job security, a pillar of American business as far back as the late nineteenth century, began to erode in the nineteen-seventies as a confluence of globalization, weakened unions, and soaring executive bonuses tilted the scales toward the wealthy and powerful. The eighties saw the rise of consulting firms which specialized in layoffs; armed with new “efficiency strategies,” these companies advised their clients on how to become more profitable and, in some cases, even handled job terminations for them, neatly coinciding with the Reagan-era rise in layoffs. Job terminations became enough of a trend that the New York Times ran a recurring column, “Layoffs This Week.”

If the seventies embraced globalized manufacturing, which relied on overseas factories with their own staffs, the nineties saw an explosion of foreign labor as work could be done offshore for a fraction of the cost. This led to a systematic reorganization in corporate America where some companies, once teeming with mega-departments filled with lifelong employees, were downsized to “essential personnel,” often the very people tasked with managing the outsourced labor replacing their colleagues. In July 1993, IBM commenced the largest mass termination in history, ending sixty thousand jobs at once, topping Sears-Roebuck, who terminated fifty thousand jobs earlier that year. The Clinton era also saw the rise of “going postal,” as gun violence in American workplaces became a trend. One could maybe attribute this, in a roundabout way, to the loss of job security due to globalization and automation.

The nineties, as you’ve no doubt been reminded, were an economic boom time in America, but as the scale of many companies grew along with their profits, so did the scope of their layoffs. Bill Clinton left office and, barely two months later, the economy began to collapse. Other than the U.S. Postal Service, Boeing (aviation), Ford (automotive), Lucent (telecommunications) and Kmart (a company which now apparently sells goods from other bankrupt companies) brought the largest mass layoffs of the early aughts. Several years later, another wave occurred, the tsunami generated by an earthquake of economic catastrophe. During the 2008 financial crisis, Citigroup dropped fifty thousand employees. Bank of America followed with thirty thousand in 2011. In 2009, General Motors had to lay off forty-seven thousand in the biggest autoworker termination in history.

These are unseemly numbers, figures best avoided by slowly cutting jobs over weeks, months, even years. Stealth layoffs are how corporations terminate now. They’ve been common since 2008 as banks, learning from their conference room bloodbaths in the eighties, kept things quiet by chipping away rather than slaughtering their workforce; even if cuts result in the same number of jobs lost, stealth layoffs don’t elicit the type of public relations hit which comes from a fifty thousand-person bloodlet. Yahoo is a master of this method; it’s been keeping its employees in a state of perma-terror for nearly a decade, even while still engaging in the occasional throwback layoff as when it shuttered its stable of ‘digital magazines’ last week.

By 2012, the last available year of mass layoff data from the Bureau of Labor Statistics (because the program itself was terminated by President Obama as part of the Balanced Budget and Emergency Deficit Control Act), there were over seventeen thousand events where more than fifty people were laid off at once. Many of these, given their volume and the physical layout of offices, which tended to favor clustering employees in open arrangements without privacy, took place in conference rooms (often in batches; safe go here, terminated over there) or via email.

As the nineties saw the rise of virtual offices based around email and webpages, workers transitioned to a scenario where their email addresses became more than the replacement for a physical mailbox. A corporate job became official when you received your email address: Your first message introduced yourself to coworkers with a company-wide blast; your last was a goodbye note to those same people. Then your email history, and you, were erased. In between, perhaps, thousands of messages: projects in various phases of completion, proof of work, meeting notes. Those, more than your presence in a cubicle, were the evidence of your employment and subsequent value to a company.

Our way of laying off now reflects our modes of communication. The story of a Florida restaurant canning its entire staff via text message brought out the Carrie Bradshaw Post-it references, but no one was surprised at the delivery method. Zirtual, a virtual assistant company, announced it was folding in an overnight mass email with no warning. George Zimmer, of Men’s Warehouse guarantees and the company’s founder, chairman, spokesperson, essentially found out he was fired via email. Rafa Benítez, the coach of Real Madrid (a soccer team of some sort?), found out he’d been replaced when the owner of the team announced it in a press conference. A Twitter employee received the news after a Yahoo notification on his phone sent him to a tweet from Jack Dorsey, the company’s CEO, announcing eight percent of its workforce was cut.

The business communication application Slack appears to be another email-killer, yet its combination of archived conversation and files, syncing among multiple devices, and search that actually works carries the makings of a more transformative office technology, one that’s changing both the way workers collaborate and how they are eventually laid off. Like email, Slack rewards active employees who assert their presence through how frequently they post. It provides a simple platform for group communication, something email claims to do when it’s only really creating multi-threaded headaches. The company’s self-professed goal is to make work easier as a result of improving the efficiency of a team, a task accomplished by turning departments into hashtagged channels and maintaining a transparent record of everything that happens within them.

For many workers — in narrow but highly indicative industries — Slack has already shifted the idea of physical office space into an idealized digital version of itself. And if venture capital has anything to say about it, the rest of the world isn’t far behind. Rather than actual rooms, employees congregate in these channels; they gossip over direct messages and build office-specific languages using emoji. Slack played its role in the Gawker layoffs because it was both the organization’s primary mode of communication and office space; terminations have transitioned from clusters of desks to digital communities, malleable teams with a built-in institutional memory that’s unbeholden to physical space.

A worker laid off by losing her access to #sadmarketing will be replaced by someone who not only occupies her actual desk but has access to every document she’s uploaded, every meeting she attended and even the pithy asides about that very meeting; all the gifs and in-jokes and Hamilton sdlfkjsd, sure, but also the contacts relevant to the job, the advantage of being able to instantly catch-up because the information has been elegantly archived and arranged for future workers. Employees whose self-worth depends on their unique knowledge of the organization no longer have that benefit. Instead of a disorganized series of private inboxes, there is now a valuable public record. The job is a body of work; the person doing it is more interchangeable than ever.

A layoff occurs when a worker loses access to a communication platform. This structure also applies to the increasingly large class of independent contractors who, because their app-based companies refuse to acknowledge their status as actual employees, experience termination through deactivation. An Uber driver who rates poorly — the bar for dismissal is a secret but is thought to be a rating of around 4.6 out of five — could open the app to find his privileges revoked without explanation. The platform which enables him to do his job carries no guarantee, and, as a worker, his rights are essentially that of a freelancer.

Is getting kicked off a service the same as being laid off? As Uber drivers push to unionize in Washington and California, the company remains hilariously obtuse when it comes to its relationship with drivers. “Your account has been flagged a final time for having significantly more cancellations than other partners,” read one driver’s reason for deactivation. “We believe Uber may not be the right lead generation tool for you. We wish you the best, but we have decided to discontinue our partnership.”

A cursory exploration into exactly how big the gig economy has become yielded no definitive answers, but the current labor pool is certainly in the millions. (A recent survey claimed forty-five million American workers, about one in five, participate in gig work, yet this includes laborers supplementing full-time jobs.) The ramifications of people, whether by choice or necessity, working for multiple companies for shorter periods of time seems to befuddle American systems tweaked throughout the twentieth century with the idea of full employment and job security. Call it the new feudalism or whatever you want, Uber’s conception of employment is beginning of the new rule rather than some grand historical aberration. Pre-union America was built on wage labor based around contingent work that, by nature, would come and go. The original meaning of layoff was a “temporary release from employment” due to seasonal or project-based cycles. It’s only the technology that’s gotten better.

Zenefits, a software company which manages the administration of human resources and benefits, has created a platform that undercuts the labyrinth of paperwork and relationships traditionally associated with a hire. (And is now sort of collapsing because it undercut the system a little too hard, but.) A new employee logs preferences for health insurance, taxes and 401(k), registers their profile, and then, with the click of a “hire” button by a network administrator, gets connected to their benefits within an all-in-one dashboard. Current regulatory nightmares aside, it’s really a win for both employers and workers. Companies can easily hire and keep their employees’ benefits up to date, while labor can simply update their preferences without suffering through bureaucratic depression.

Zenefits also does for job termination what it does for hiring. Whereas a few years ago, a layoff meant severing an employee’s health insurance, 401(k) administration and payroll processing separately — an hour-draining series of paperwork, scanning, faxing and follow-up calls — access to benefits can now be cut by unchecking a box. Rather than investing in an employee, owners can add and drop based on what their company needs in real-time.

This ease of labor-swapping makes human resources feel like fantasy sports. If I’m running a company and the data tells me I need rebounds while you provide assists, I’m sending you back to the bench. Your previous stats, in the guise of healthcare and 401(k), remain associated with your account, and you’re welcome to carry those signed documents to your next job, as long as they use Zenefits, too. You’ll also still be able to access your vacation and time-off log, which the platform suggests can be used for “unemployment data purposes.” But really wouldn’t that time be infinite?

Zenefits won’t administer your exit interview, but I’d still be worried if I worked in traditional HR. Just as the Uber driver will be replaced by a robotic, “better” version of himself, so will human resources departments. Zenefits software classifies termination as either voluntary (quitter) or involuntary (fired), and can even mark you as regretted loss (they consider your layoff profound because you “had high potential” or were a “key contributor with a significant impact”) or non-regretted (you were not regarded, basically, at all).

“The willingness of workers to discard status privileges like desks and offices is not just a sign of giving in to executive demands for cost control,” writes Nikil Saval in Cubed: A Secret History Of The Workplace, his excellent history of the American office. “It also suggests that the career path that defined the white-collar worker for generations — from the cubicle to the corner office, or even from the steno pool to the walk down the aisle — is coming to a close, and that a new sort of work, as yet unformed, is taking its place.”

Job security will be left to decay in the supply closets of skyscrapers. The future office space is within a chat application; future departments are virtual rooms where work is transparently archived for future versions of you. This means job roles take on a more concrete meaning while the person doing the job is less important than ever. The best full-time employee is an efficient roleplayer; the worker, tied to her benefits, is free to float where she chooses, stitching together part-time jobs, connecting to health insurance where it’s offered, cutting back the red tape which makes working for someone new such an arduous process. The worker is tied to her past through employer performance ratings, which, along with certain digitized forms like the W9 and 1099, will follow from job to job. The “non-essential worker” tag or a bad driver rating could become our modern Scarlet Letters.

Work itself already shares the qualities an application. Like email or the office door before it, the worker opens their platform when they want to make money. Their profile seamlessly connects to other apps, the Slack channel which allows collaboration with other profiles, the Zenefits dashboard which ensures their health insurance is valid if they crash their Uber car. Layoffs are now the denial of access rather than a person’s severance from a traditional job. So it goes. Jobs have long been the stand-in which workers used as a shorthand for personal identity rather than what they really are: a thankless compromise necessary to participate in capitalism.

No More Books by Men

by Eva Jurczyk

The last male-authored book that I’ll ever review was about pirates. As a lifelong rule-follower, I didn’t read any other press coverage of the book before submitting my review to Publisher’s Weekly, for fear of being unduly influenced or accidentally plagiarizing. Only after I filed did I Google the book and its author: He was dubbed “a master of historical fiction” by practically every major Canadian paper, with no mention of the fact that the main character uses fine Elizabethan English for his internal monologue, but scarcely intelligible pirate-speak for his speaking voice. “An exciting page-turner!” others claimed, with no notes about the senseless plot construction or the weird aside about a room overflowing with creepy dolls that appears in one scene and then is never mentioned again. In the same batch of review copies as the pirate book, I received an English translation of a work by a moderately successful Quebecois writer, who had recently been featured on the literary-reality television program CanadaReads. Her book was one of the best I read all year; it received a short-form review in one Canadian newspaper and is currently a hundred and fifty thousand places behind the pirate book on the Amazon best-seller rankings.

There is a trick of Pavlovian conditioning that I’ve been using lately on my best girlfriend. She is a person who sends a lot of text messages and a person who does a lot of Crossfit, so that particular Venn diagram means that she is she a person who sends a lot of text messages about Crossfit. As a person disinterested in both Crossfit and long text conversations, this arrangement works poorly for me. So, when she sends a non-Crossfit related text, I make my best effort to respond. A message about the Leon Bridges concert? Here is your treat in the form of a smiley emoticon. A message about deadlifts? Crickets. This strategy has not changed the volume of texts she sends, nor the number to which I reply — about thirty percent — but it has slightly changed the volume of Crossfit-related to non-Crossfit-related texts.

What if male-authored pirate books are the Crossfit texts of the publishing world? And what if I, in my capacity as a book reviewer, have the power to shift the ratio of rubbish pirate books by dudes to meaningful literature by women? The publishing houses will keep putting out books about buccaneers and they’ll keep appearing on my monthly review list but what if I don’t expend any mental energy or spill a drop of ink about them? This wouldn’t change the number of books by women that are published every year, nor the total number of books that Publisher’s Weekly reviews — some eight thousand per year, mostly for librarians, the media, and booksellers — but if someone is reserving all of their mental energy and all of their ink for female-authored books, then perhaps these books will be covered sooner, the gems among them celebrated louder, and the publishing industry will slowly adjust the definition of the type of book that is deemed worthy of attention. It seems like a better strategy than doing nothing, so moving forward, I’m only going to review books written by women.

VIDA, an organization that advocates for women in the literary arts, has compiled data for the last five years about coverage of women writers in major literary journals, publications, and press outlets — which drive not only book sales, but consideration for grants, literary awards, teaching positions, and fellowships. The first VIDA count found that in 2010, the New York Review of Books covered three hundred and six books by male authors and fifty-nine by female authors. Since then, several major publications have been shamed into changing their editorial policies to make coverage more equitable. In the 2014 count, several publications, including Harper’s, Granta and The New York Times Book Review, moved closer to gender parity in their coverage. Some of these changes were small, like Harper’s coverage by and about women writers increasing from 27 to 32 percent between 2010 and 2014, but the New York Times Book Review and Granta, increasing coverage from 36 to 47 percent and 35 to 48 percent (respectively) seem to have responded to the counts with a real effort to diversify coverage. Others, like the Times Literary Supplement and The Nation still have huge gaps in their coverage, with work by and about women writers comprising less than thirty percent of the content of both publications in 2014.

The argument against gender parity in authorship is probably the same argument that is made when, year after year, there are no female filmmakers nominated for film awards: There just aren’t as many films, much less quality ones, made by women. And there are fewer books by female authors published by literary presses, so there are fewer books by female authors that can be covered in literary journals, so there is less female talent covered in literary publications from which publishers, granting organizations, and universities can draw talent. Maybe women are just inherently less literary, their output less worthy of serious critical attention? But male writers don’t receive critical attention because they are good; they get coverage in the New York Review of Books because they are men. And women’s books should be talked about not because they are literary geniuses and men are witless scribes, but because they are creating art from the point of view of fifty percent of the citizens of our planet. My argument, in other words, isn’t that books by women are superior to those by men — they sometimes aren’t! — but that when I’m criticizing the work of a female writer, I’m rarely arguing against anyone. Whether I have something positive or negative to say, I’m usually the only one saying anything at all because literary people just don’t view books by women as being as important as those by men.

Last year, Jezebel ran a story by a young writer, Catherine Nichols, who was frustrated by the lack of attention she was getting from agents for her new novel and thought, “With my name, maybe my novel was taken for ‘Women’s Fiction’ — a dislikable name for a respectable genre.” Using the exact same cover letter and manuscript pages, she sent fifty queries to agents as Catherine and fifty as George Leyer; Catherine received two requests back from agents to view the full manuscript, while George received seventeen. A couple of years ago, the writer and University of Toronto lecturer David Gilmour spoke to Hazlitt about his reading and teaching habits and said that he’s not interested in teaching books by women, that he doesn’t love women writers enough to teach them. You don’t even have to be a self-important, limp-dicked nitwit to feel that way. Tramp Press, an independent Irish publisher founded by two women, requires that authors of unsolicited submissions cite their literary influences in query letters. Sarah Davis-Goff, one of the founders, analyzed the press’s one hundred most recent submissions and discovered that female authors comprised just twenty-two percent of the influences listed.

Often we can’t get this right even when we’re trying. In 2014, the writer and illustrator Joanna Walsh wrote about starting the #readwomen2014 campaign in reaction to the VIDA numbers. Writing in the Guardian, Walsh said that the #readwomen2014 hashtag did plenty for awareness of inequality but little for the practical problem of how to get published, get read, and get praise for good work as a female writer. Her article, enumerating the complaints of vital women writers like Lionel Shriver and quoting the Guardian’s own literary editor, ran on a blog in the women’s section of the Guardian, rather than in that paper’s respected Books vertical. Maybe there is a perfectly boring reason for this, like who the assigning editor was, or maybe the Guardian, even with its favorable coverage of lady-writers, considers advancing readership of female writers to be a women’s, rather than a literary, issue.

In 2014, Amanda Nelson wrote in Book Riot about the year she spent documenting everything she read in a spreadsheet. Looking at her reading data she was pleased to learn that without paying attention she was already reading evenly between men and women, but she also saw that, without paying attention, she’d read almost no people of colour, which is why she now pays attention. To transition from awareness of inequality to outcomes that address that inequality, attention must be paid. To keep us from drowning in pirate books, to make literary publications reflective of all readers and writers, to make a livelihood as a writer accessible based on one’s talent rather than one’s anatomy, attention must be paid: by organizations like VIDA, by publications like the Times Literary Supplement and by individuals like me.

The books written by men will still get covered, just not by me — the female-written books, some of which might otherwise have had to wait months post-publication for a printed review, will be my top priority. I’m still going to read books by male authors — but rather than call dibs on the review copy, I’ll put them on hold at the library. I don’t expect that reviewing fewer pirate books and more female-authored books will change the publishing industry, just like I don’t expect a hashtag or VIDA counts to upend hundreds of years of ingrained inequity, but lots of small decisions made by lots of individuals might add up to something.

Job Open (Again)

by The Editors

For the last two years, the Awl, while carrying on much of its original mission and commitment to publishing voices from far and wide, has been largely obsessed with structures, particularly the ones undergirding our weird dumb moment of money and food and cities and apps. We mulled the new logistical apparatus under which we will all toil imminently and forever; screamed about Facebook and grain bowls; and taked our fingers numb. And it’s been fun. (For the gingers anyway, hahaha, sorry!!!) But now it’s time for something new — for the Awl to embody somebody else’s weird obsessions.

So! The Awl’s current editors are departing and it is looking for a new editor(s)-in-chief. [UPDATE: NEVER MIND.] Item is in very good condition, with normal signs of use; it is recently refurbished and ready to provide years of service to its next caretaker. There is truly nothing else like it, and not just because it’s the one of the last truly independent media companies still standing.

The Awl is a nose-to-tail content operation, so we’ll re-use the description from the last time it looked for a new editor.

Applicants need to be seriously entrepreneurial in nature and welcoming of risk. The editor-in-chief will need to be able to execute long-term dream-schemes while responding to the horribly immediate. The job combines the thrill of executing a larger vision with the tyranny of managing a constantly overflowing inbox. This role has a large amount of autonomy, and therefore applicants need to have the attention to detail of a great managing editor, the confidence of an editor-in-chief and the moral compass of a columnist. Most importantly, we are primarily a horizontal and non-hierarchical organization, with an extremely strict no-assholes policy. Behavior is as much prized as talent; genuineness is as valuable as genius.

Candidates should be based in New York City, or at least within commuting distance of the Awl’s office at the foot of several luxury condo buildings in lovely, historic DoBro. Interested parties should email the Awl’s co-founder and editorial director, Alex Balk, with their vision for the next version of the site. (First test: finding his email address.) Discretion is assured!

We’ll be hanging out (and publishing) for a while longer to help things along as appropriate/necessary/desired, and to answer any questions about how the coffee grinder works.

— John and Matt

Craig Finn, "No Future"

Everyone complains about Mondays but it’s not like Tuesdays are any prize either, right? Anyway, here’s Craig Finn covering Titus Andronicus. Enjoy.

New York City, February 21, 2016

★★★ The warmth and brightness, alive with the hope of spring, had weakened to ordinary non-coldness and a dull light-gray sky. It was acceptable for strolling the thirteen blocks back from the older boy’s haircut. The streets were neither empty nor alive with enjoyment. Airplanes moved below the cloud ceiling. By late day the clouds were strained and rumpled like bedclothes with someone sleeping fitfully in them. Parts were almost blue, or flushed with golden light. After dark, a shine appeared on the paving tiles of the roof deck across the street. A quietly pattering rain landed on a hand stuck out the window.