New York City, March 21, 2016

★★★★ The snow had been light but enterprising. It stuck to the sides of the balcony rails more thickly, if anything, than to the balconies themselves. It had failed to whiten the pavement but it traced the delicately tapering lines of the tree branches all the way out to the thinnest new twigs. The clouds grew pearly and began to separate. Puffy little lumps of snow fell off the top of the scaffolding and looped around to land underneath it. The sky went from half-blue to two-thirds on the walk to the pre-K dropoff, and surpassed three-quarters on walk back. The early afternoon was not just clear but intensely so. Every bit of snow was gone, but so was the milder dampness that had come with it. The wind was dry and getting ever colder. It lifted a plastic bag high off the sidewalk and wrapped it around a branch of a tree. The bag jumped loose and clung to an even higher branch. The four-year-old asked if he might be allowed to throw bags out the apartment window to watch them fly.

Welcome to Faceslash Island

The NYPD plan to rid the city of face slashings is called “Operation Cutting Edge.” If it is as effective as most initiatives under the De Blasio administration, one might consider a new summer commuting outfit.

After Tipping

by Patrick Abatiell

Kate Edwards has been a hospitality consultant in New York City for almost a decade, but before that she was a maître d’ at one of the landmarks of New York’s downtown dining scene during its heyday in the late nineties and early aughts. While the job came with a lot of perks — especially for women, who were regularly given gifts by repeat customers, like clothes from people in retail — for her actual take-home pay, Edwards relied mostly on “handshakes at the end of the night,” meaning tips she received from guests after she’d found them a table.

Edwards eventually discovered, however, that males were routinely palmed far more than women in the same position. The handshake tips normally came from men, and for Edwards, it was obvious that the exchange of cash was part of a ritual designed to shore up the power relations between guests and restaurant employees. “Men tip men to demonstrate who’s in power,” she said. “So if I go in and I’m the man and you’re the maître d’, I’m tipping you to show you that I’m the guest. Now you’re going to give me something. But let’s not misunderstand, I’m in charge.” For a man confronting a female employee, on the other hand, the power dynamic is simply assumed: There’s no need to negotiate it, no need to feel threatened. “I don’t have to worry about power in front of you,” Edwards said. “Your job is to get me a table.”

This disparity meant that a female maître d’ received a considerably lower weekly income. Edwards brought this to her boss’s attention, and asked for a raise in order to even things out. At first, he registered some surprise, citing the figure he thought she took home. “No,” a colleague corrected him, “that’s for the guys.” Ultimately, Edwards’ employer agreed to raise her hourly wages to ensure equitable compensation.

According to Restaurant Opportunities Centers United, a labor advocacy group, close to seventy percent of the nation’s tipped workers are women. The national minimum wage for tipped workers is far less than the national or statewide minimums for workers in general — it has been frozen at $2.13 an hour since 1991 — and since most, if not all, of a tipped worker’s hourly income goes to taxes, most are forced to sustain themselves on their tips alone. Since pay based on gratuity can vary significantly from day to day and from week to week, workers are often forced to endure unsafe working conditions, hostilities from their supervisors, and harassment from co-workers, employers, and customers. As the ROC notes, thirty-seven percent of sexual harassment complaints to the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission come from the restaurant industry, making it the largest source of complaints of any industry nationwide.

Recently, several prominent figures in the New York dining world have announced plans to address some of these issues. They will accomplish this, they claim, by eliminating tipping altogether from their restaurants. The trend is being spearheaded by Union Square Hospitality Group (and Shake Shack) founder Danny Meyer, who announced plans last October to gradually replace what he calls the “icky” custom of tipping in all thirteen of his full-service restaurants with a system that he’s calling Hospitality Included. (I should mention here that in the past six years, I have worked in two of them.) Since then, Andrew Tarlow, who was instrumental in creating the modern Williamsburg dining scene in the early aughts, has followed suit, along with other restaurateurs, in varying degrees, like Gabe Stulman of the “Little Wisco” empire, Anita Lo, and David Chang. To generate momentum, Tarlow’s company also designed a “non-proprietary” gratuity-free logo which it hopes will be used by other operators to create a coherent visual vocabulary to alert the city’s diners as the trend picks up steam.

Strategies differ from restaurant to restaurant, and company to company, but in general, the broad strokes are consistent: Eliminate gratuity, hike menu prices, and raise worker wages. In Meyer’s gratuity-free restaurants, for instance, prices have risen around twenty-five to thirty percent in order to increase overall restaurant revenue. Meyer’s lowest-paid employees, who would normally be paid the statewide hourly minimum of $9, will immediately receive a $2-an-hour wage hike. (As Eater’s Ryan Sutton has pointed out, however, this still keeps them far below the city’s $14.30 living wage.) According to Erin Moran, the Chief Culture Officer for Meyer’s restaurant group, instead of receiving a small hourly wage plus tips, Meyer’s servers, bartenders, and other front-of-house workers, will see an increase in their hourly pay, and will also participate in a revenue-share program based on the restaurant’s overall sales.

Mainstream press coverage has tended to take it for granted that the no-tipping trend is genuinely reformist, if not borderline charitable. What has been less emphasized, however, is that the move to increase menu prices and adjust workers’ hourly pay, particularly at the higher end of dining, is primarily a business decision. In New York City especially, it will mitigate the impact of impending minimum wage legislation at the city and state level for both fast food and full-service restaurants; starting in January, new minimum wage laws effectively raised hourly wages for tipped workers by fifty percent, from $5.00 to $7.50 per hour, and Governor Andrew Cuomo is leading a charge to raise the statewide minimum for all employees even further — to $15 an hour over the next three years.

It’s thought that increasing the amount of revenue that comes directly into restaurants will enable operators to better manage this new set of financial obligations in an industry notorious for low profit margins — Abram Bissell, head chef at the Modern, claims that his restaurant operates at margins of about seven percent. It also opens restaurants up, however, to new forms of risk, like higher taxes. Leah Campbell, HR and Communications Director for Tarlow’s group, told me that her company’s workers were surprised to learn that employers like Tarlow receive a personal tax credit for employing tipped workers. According to Campbell, the original intention of this measure was to ensure honest reporting of tipped wages, but it now remains as something of a perk for owners to keep their employees reliant on tips. “It is our understanding this law is in place to incentivize owners to make sure tips are reported for taxes,” she told me, “but it now has the effect of being an incentive to remain in the broken system of tipping.” Campbell is likely referring here to a FICA tax credit that allows restaurant owners to recuperate taxes on employee wages earned through tips (which is income earned beyond their hourly wage.) For obvious reasons, this credit is beneficial to employers, but it also effectively operates as a loophole that rewards keeping workers employed in a tip system, since doing away with tips means that owners are now responsible for paying FICA taxes on their employees’ full salaries or their far higher hourly incomes.

Besides this, paying employees directly also means that operators are now fully responsible for covering expensive credit card processing fees, which, at least in Meyer’s case, have been taken out of employees’ pooled tips since 2011.

The no-tipping movement has already started to pay off. Although a recent Grub Street report indicates that Romans has experienced some turbulence with the rollout of gratuity-free service — some long-standing employees have expressed concern over the prospect of taking a pay cut in order to make wage distribution more equitable restaurant-wide — things seem to be going more smoothly for Meyer. A recent report announced that, despite raising both manager salaries and hourly wages for line employees, the Modern had “its most profitable month in history” last December. The move has also seemed to have a positive emotional impact on at least some employees whose workplaces have been affected by it. A front-of-house employee at one of Meyer’s restaurants told me, “Overall, I’m comforted by the fact that my management team is paying me, and a drunk guest isn’t forgetting to write in the tip line and leave me [without] my night’s earnings.”

But, for all the attention that the gratuity free trend has generated, it doesn’t fully address the breadth of wage problems faced by restaurant workers, many of which are embedded within the structures of the restaurant world. The profit margins Bissell alludes to are not limited to his own establishment; industry-wide, businesses operate along similar lines. This makes cost-cutting vital, especially in cities like New York, where rent is a high fixed cost — even Meyer, one of the city’s most successful and iconic restaurateurs, was forced to move his flagship, Union Square Cafe, following a rent hike. The variable that remains most within owners’ control is labor; as Moran explained to me, throughout the industry, the conventional thinking is that profitability all but depends on reducing labor costs. This is why, she argues, it is important that a company with as much experience and financial acumen as Meyer’s USHG is pushing the industry to re-think how workers are paid. “Our goal right now is to have really strong execution on our plan and to achieve our targeted business results and to be able to share that with the world, and to say, ‘Hey guys, guess what? This is a smart business strategy. Because it does positively impact your bottom line.’ That’s our hope.”

At this moment of heightened public attention to the ways restaurant workers are compensated for their labor, it’s an opportune time to think about the mechanics of this distribution. Even though the no-tipping trend promises higher wages for some and less workplace anxiety for others, it still does not ensure equity all around. The front-of-house employee I spoke with was concerned, she told me, because “I don’t know how much a BOH employee gets paid — that’s not been announced, because it’s individually based. This makes me wonder if gender inequality is still at play.” This inequality would be in keeping with industry standards. Women occupy only nineteen percent of chef positions industry-wide, and in any given position, a female worker can expect to earn seventy-nine percent of what a male counterpart earns. When you add race as a consideration, the outcome is even worse: According to the ROC, a black female server makes sixty percent of what a white male server does.

Race is a particularly tenacious issue in the service world, and as ROC founder and Director of Food Labor Research Center at University, Berkeley, Saru Jayaraman, reports in her recent book, Forked: A New Standard for American Dining, practices of racial discrimination are deeply imbedded in restaurant culture, especially when it comes to hiring, compensation, and promotion. In its 2015 study, Ending Jim Crow in American Restaurants, the ROC noted that the most highly compensated tipped positions in the industry are held by white men, and “even those people of color employed in these typically higher wage categories earn substantially lower average wages.” People of color are routinely relegated to back-of-house positions, like line cooks, prep cooks, and dishwashers; in general, there is a sharp divide in terms of overall earnings between front-of-house and back-of-house employees, and the relative invisibility of these workers renders them one of the most vulnerable and undercompensated segments of the industry’s work force.

While a no-tipping system may certainly begin to even the playing field between employees who hold front-of-house positions and their historically less well compensated back-of-house counterparts, it does not ensure that high-paying positions are available to all employees regardless of race, nor that standards for methods of career advancement (like promotions and raises) are race- or gender-blind. Some twenty-eight percent of restaurant employees who have been denied a promotion cite race as the primary cause.

Finding a way to address the problem, however, has proven challenging. As Jayaraman explained to me over the phone, it has been far easier to work toward addressing wage issues because there is greater popular energy behind them, as well as a far more specific legislative path to follow. “Certainly there’s a much more clear solution to eliminate the two-tiered wage system,” she said. “In the case of racial equity, it’s much more complicated; the policy solutions are not that clear. So it’s a much harder road, not even just in terms of winning support and educating the public, but even in figuring out what is the policy solution that will actually address this issues.”

Both Campbell and Moran acknowledge that much work needs to be done in order to establish a more equitable restaurant culture. Campbell wrote to me: “Are we concerned with a world where the tip credit wage is $2.13 and are we aware that across the industry harassment issues are rampant and unaddressed perhaps because service staff’s pay is supplied almost entirely by guests? Yes. Do we see the value in raising expectations and standards everywhere? Of course we do. Can we do better at addressing discrimination in our industry? Yes and we have to.” While neither she nor Moran could speak in any specific terms about what steps their respective companies were taking to address these issues, nor about any present plans for their organizations to take them up at a later date, both insist that the willingness and the energy to look for solutions is there.

In lieu of relying on restaurant owners to police themselves in this regard, Jayaraman suggests that one step toward pushing companies to redress these problems may be educating diners themselves to start asking restaurants about their labor practices. Citing the moderate success of sustainable food movement in encouraging consumers to find out about how their food is sourced, how it is cultivated, and how it is distributed, Jayaraman sees some potential in teaching restaurant diners to push these questions further, and to make discerning choices about where they spend their money based on the working conditions of the people who serve them their food. As she put it over the phone, “If you can ask about, is this tomato organic, and how are the chickens treated, can’t you ask how the people are treated?” In her book, she uses her own experience as an example, citing instances when she has approached restaurant owners and managers to compliment the food and service but also to express concerns over apparent racial divides among workers, or to ask specific questions about worker benefits and compensation.

I wondered, hypothetically, how one of Meyer’s restaurants would respond to diner feedback along the lines Jayaraman proposes in her book. I asked Moran what if somebody dining at Gramercy Tavern, for instance, approached a manager to ask about the appearance of racial divide between servers and bussers, front of house and back of house? “That would be, like every point of a guest’s experience, something that we much better want to understand and think through as management and leaders of each business,” she told me. “We certainly want to encourage all of our guests to provide feedback on their entire experience and that should be inclusive of what they are seeing in terms of the diversity of our workforce, similar to how they’re experiencing the physical environment or the hospitality or the culinary experience.”

Moran seems to suggest, then, that even in the absence of any explicit plans to address these larger issues of workplace justice, Meyer’s company would be willing to take such concerns from guests into consideration. With the new public interest in restaurant pricing and compensation, now is the perfect time to push for these changes, and to think more critically about deeply rooted challenges faced by America’s eleven million restaurant employees. As Edwards told me, “there’s a lot that people need to think about and evolve in their thinking. It’s not just tipping or not tipping.”

Photo by Donald Lee Pardue

New York City, March 20, 2016

★★ Clean clouds, blank as paper, floated on the sky seen from bed. They gathered into something unpleasant, another of late winter’s near-daily interludes of gloom, carrying past the season’s end. Midafternoon unexpectedly broke it, though, and the streets filled with sun again. Aged trash was in the treetops on Broadway but leaves were in the trees on 72nd, and there was a persistent soft edge to the cold. Not persistent enough, though. In the course of a piano lesson the light and softness departed completely. A truck laden with salt turned the corner, calcium chloride fluid sloshing in its translucent tanks. One palm frond lay in the street. By bedtime there were snowflakes passing in the lights, whitening the upholstery on the luxury building’s rooftop chairs.

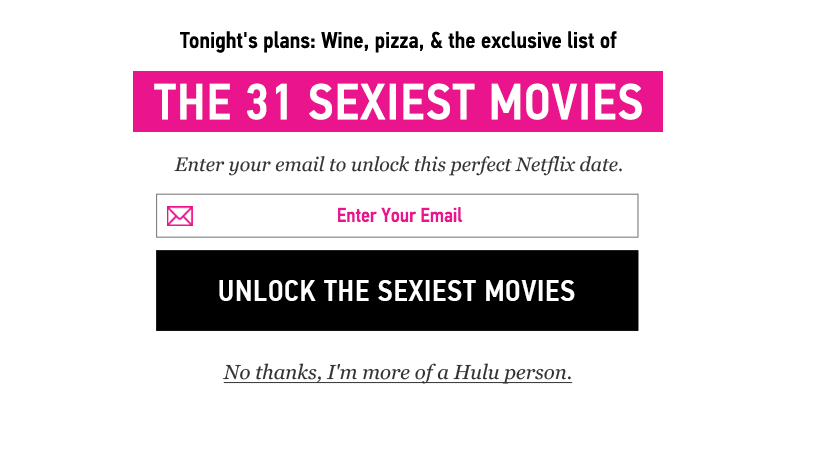

Lines of Text I've Clicked to Exit Pop-Ups, Ranked From Least to Most True

by Julia Phillips

35. Marathons are easy

34. I’m not interested in celebrity friendships

33. I already have a bikini body

32. I know it all

31. That soap scum isn’t bothering me

30. I’m not interested in free recipes

29. I don’t want to see celebs without makeup

28. I know exactly how much my stove installation will cost

27. I don’t enjoy long, luscious, clump-free lashes

26. I am happy with low traffic

25. I’m not interested in increasing my growth

24. I’d rather stay in the dark about this and let others have the advantage

23. I don’t like winning

22. I don’t need sex tips

21. I’m not looking to lose weight

20. I’m not interested in winning free things

19. I’m not interested in beauty tips

18. I don’t care about the future

17. I prefer to pay full price

16. I don’t think our generation needs a voice

15. I don’t like exclusive deals

14. I have infinite energy

13. I don’t want 25,000 more visitors to my site

12. I’m not interested in protecting my skin

11. I don’t want to find out if he’s the one

10. I’d rather go buy ketchup

9. I don’t like to get more customers

8. I’m not interested in the 12 shoes every woman should own

7. I don’t need today’s most important stocks

6. Keeping up in the IT world is unimportant to me

5. I prefer more popular cars

4. I’m not a fan of shiplap

3. I like eating unhealthy food

2. I’m all set for right now

1. I’ll stay out of the loop

My Land Is Not Your Land

by Alex Cocotas

Impact craters and wreckage of target plane along dummy airstrip, live-fire zone, Nahal Masor basin, the Negev

Latitude: 30°45'14″N / Longitude: 35°10'31″E // 22 November 2011

Fazal Sheikh, from the Desert Bloom series

Everything in Israel returns to land. When Israelis speak of their country, they rarely use the word “Israel,” but, most often, ha’aretz — the land. Pre-state Palestine is eretz Israel. A well-known song, frequently invoked during wartime as a vapid political slogan, by the right and the left, states, “I have no other country (eretz) / even if my land is burning.” Knowledge of Israeli politics is ultimately superficial — Netanyahu said, Rabin said, Ben Gurion said — to truly understand Israel, one must, as the early Zionists advocated, return to the land.

Few countries have such an obsessive, and uncertain, relationship with its constituent territory. In fewer countries does the government, directly and indirectly, control more than ninety percent of the land. And in even fewer countries is the land subjected to such frequent and continuous manipulations, permutations, and radical reorganizations: spatially, conceptually, and residentially. Its inhabitants are expelled, new inhabitants resettled. Nature is iterated, imposed, and subverted. The visible surface is a palimpsest of development and destruction, dreams and despair, where a copse on an arid ridge or a pair of tire tracks in empty expanse are imbued with ideological character.

It makes, however, for a difficult artistic subject, liable to become a deluge of senseless detail or an aesthetic gloss signifying nothing, requiring so much explanation that you lose sight of the art, or simply reduced to a series of pretty landscapes in lieu of any context. The photographer Fazal Sheikh’s new work Desert Bloom, part of his Erasure Trilogy, is thankfully neither; it is one of the most comprehensive works about the land of Israel, visual or otherwise, succeeding at once as artistic creation and critical inquiry.

Sheikh, a MacArthur fellow, takes as his subject the Negev desert, the country’s most sparsely populated region, but which also accounts for fifty percent of its land mass. It is, at first glance, a curious choice: It is not rich in biblical history, nor does it loom large in the popular imagination as a site of contemporary wars and conflicts. There is not much there, or so one would think. But, like the rainwater that winds its way across the region’s ridges and canyons to collect in basins and stream beds, it seems all of Israel’s history filters down to the Negev.

Desert Bloom consists of a series of large aerial photographs, forty-eight in total: both the year of Israel’s establishment and, incidentally, the length of Israel’s occupation in the West Bank and Gaza at the time of its first exhibition last year. (Desert Bloom will be shown at the at the Slought in Philadelphia until May 1st and at the Brooklyn Museum until June 12, as part of the of the “This Place” exhibit.) The work is defined by paradox: The unmediated, decontextualized photographs superficially appear as abstract images, a bewildering and impenetrable grid, each picture like a mysterious gesture from a stranger on a passing train — tawny scabs, striated sand, geological wrinkles, traces of human presence, planning, and infrastructure — but an accompanying pamphlet serves to decode the images, revealing the research and care that went into selecting each image, and how each one is anything but a haphazard collage of aestheticized space and form.

Formations simulating enemy installations for military manoeuvre training, live-fire zone, the Negev

Latitude: 30°57'14″N / Longitude: 34°39'25″E // 13 November 2011

Fazal Sheikh, from the Desert Bloom series

Each photo is numbered and appears in the pamphlet with its lateral coordinates, which are collectively plotted on a map of the Negev, while a short paragraph provides information and context. Altogether, the photographs and the pamphlet tell a wide-ranging and comprehensive history of the land and its utilization: an array of approaches to desert agriculture, traditional and modern; ruins and remains from the Nabatean and Byzantine eras; seismic experiments; environmental degradation; afforestation by the Jewish National Fund (a quasi-governmental organization that controls a significant amount of land in Israel); the foundations of expansion for the region’s Jewish communities; and military installations, both British and Israeli, permanent structures and transitive training grounds. The central concern, however, is the fate of the region’s Bedouins.

Like the residents of Yaffa, Lydda, and numerous other villages, Bedouins in the Negev fled or were expelled from their homes during the war surrounding Israel’s establishment in 1948. These settlements sometimes became the site of Jewish communities, like Ofakim; or were incorporated into agricultural developments and newly declared military zones, preventing former inhabitants from returning; or they were simply destroyed. Many displaced Bedouins were resettled in the nineteen-fifties by Israel’s military government, which ruled over Arabs in Israel until 1966, and these new government-directed settlements became, bizarrely, what are now called “unrecognized villages.” Today there are dozens of such villages across the Negev, hardscrabble places consisting of tents and hastily-built structures. They often lack access to water and electricity, let alone health and educational infrastructure, because the Israeli government does not recognize their right to exist.

Under the pretense of reclaiming state land, the government has repeatedly destroyed Bedouin “unrecognized villages,” which are subsequently rebuilt by residents. (Many Bedouin also self-demolish under heavy government pressure). The village of Al-Araqib, for example, was recently demolished in December for the ninetieth time. The phrase “unrecognized villages” is Orwellian cover for a process that seeks to justify the expulsion of families from their houses, destroying their property, separating them from their sustenance and traditional way of life in an effort to induce Bedouin “sedentarization,” another obfuscating term. The ultimate goal is to drive these residents, who are mostly farmers and herders, off their lands and into government-sanctioned townships, which are essentially Bedouin ghettos with endemic poverty and crime. It is often couched in parochial concerns for the residents’ well-being — the familiar patina of benevolent civilization — and conveniently ignores Bedouins’ stated desire to remain, which could easily be facilitated by connecting the villages to power or water lines, or building rudimentary infrastructure, like schools or health clinics.

The fate of the “unrecognized villages” and the broader Bedouin community cannot, however, be extricated from the government’s broader policy of Judaization in the Negev, an increase in the region’s Jewish population to maintain demographic superiority (similar policies have been implemented elsewhere in Israel, such as in Jerusalem and the Galilee). Exploring this policy underpins much of Desert Bloom, even in those photos which initially appear unrelated. Afforestation by the Jewish National Fund, for example, is often just arbor cover for dispossession — expelling Bedouin villages to plant forests in their place and then clearing the way for new Jewish communities nearby, whose residents are enticed with handsome government benefits and promises of a high quality of life, such as great jogging trails in a recently planted forest. This policy is further supported by an uneven distribution of resources. While Jewish communities are supplied with modern drip agriculture, Bedouin communities must use traditional runoff agriculture (more than seventy-five thousand Bedouin lack access to running water). The overarching objective is to limit the growth of Bedouin communities as a dispersed population, corralling them into insulated townships where they are more easily controlled, poorly served by public transportation and lacking economic and educational opportunities, sequestering them at the state’s mercy.

Underground communications and power lines to the border fence and intersecting seismic test line, border zone between the Negev and Egyptian Sinai

Latitude: 31°7'40″N / Longitude: 34°18'49″E ; // 13 November 2011

Fazal Sheikh, from the Desert Bloom series

Such policies would be familiar to Palestinians in the West Bank. There, the IDF also declares closed military zones to facilitate expropriation of land; settlers have unfettered access to water relative to their Palestinian neighbors; and government policy has effectively pushed the Palestinian population into a chain of isolated islands with limited scope for expansion. This, then, is the subtle power of Desert Bloom: It exposes the false dichotomy that is often drawn between Israel and the Occupied Territories, between the enlightened democracy of tech startups on one side and the nearly fifty-year military occupation on the other, a false dichotomy of autonomous political spaces with little overlap between them. The same policies, informed by the same ideology, travel freely across the Green Line, the demarcation of Israel’s pre-1967 borders, refined on one side and exported to the other, and vice versa.

While the work’s title, Desert Bloom, first appears as an ironic play on David Ben-Gurion’s famous exhortation “to make the desert bloom” — it is clear from the pictures that not much is literally blooming there — Sheikh demonstrates that it really is blooming, in a way, as a hot house of Israeli politics and policies. Beyond the land policies, Israeli soldiers train at mock Palestinian villages in the Negev; IDF pilots drop mock bombs in desert canyons; and the country’s nuclear deterrent, the true guarantor of its existence, was produced at a “textile factory” near the city of Dimona. The Occupation, the foreign incursions, and the aerial bombardments — that is, the things that define Israel in much of the world — were first practiced and perfected in the Negev.

But there is another aspect of Desert Bloom, which will likely be lost on many who see it: Sheihk’s engagement with aerial photography, a longstanding tool of governments and urban planners, which has a long history in Israel-Palestine as a means of fortifying and extending state power. Some of the earliest aerial photographs of eretz Israel were taken during World War I, and later, the Israeli government has used aerial photography to thoroughly map the Occupied Territories — maps which remain a closely guarded secret. More recently, a different kind of “aerial photography,” drones, have been used to carefully monitor, and bomb, the Gaza Strip, creating an eerie new paradigm of post-territorial military occupation.

Abu Asa family homestead, Bir Hadaj, the Negev

Latitude: 31°0'60″N / Longitude: 34°43'4″E // 9 October 2011

Fazal Sheikh, from the Desert Bloom series

At the beginning of the Second Intifada, Edward Said wrote, “[The Palestinians] had no detailed maps of their own at Oslo; nor, unbelievably, were there any individuals on the negotiating team familiar enough with the geography of the Occupied Territories to contest decisions or to provide alternative plans.” New technologies and new means of dissemination have allowed activists and organizations to document and analyze geospatial developments in the Occupied Territories for the first time, everything from the method and mechanisms of settlement development to the organizational logic of roadblocks, an approach known as forensic architecture, creating their own maps and bringing them to a wider audience. The Israeli architect and intellectual Eyal Weizman, a pioneer in the field and a collaborator of Sheihk’s, writes in his book Hollow Land that these projects “extend our political understanding of the conflict to a physical, geographical reality,” which can subsequently be used to oppose and disrupt the conflict. Desert Bloom brings this idea beyond the Green Line, back to the roots of the state’s establishment.

Sheikh’s work thus engages with this tradition of aerial photography, but ultimately subverts it. Like Prometheus come down from Olympus, Sheikh exposes the opaque logic manifest in myriad disparate actions, no longer experienced as a series of discrete impressions; the machinations of that contemporary god, state power, wrangled from secretive councils and made available for all to see. The mists of subjectivity clear, and we are left with the land: immemorial, writhing, recording.

Starchild & The New Romantic, "I Didn't Mean to Turn You On"

Here’s a thing: Have you noticed that it’s sill light out in the evening now? How remarkable is that? Even through all the tiny turmoils that each day takes out on you there is still a little bit at the end that lets you kid yourself into thinking it just might be okay. Anyway, here’s a cover of the Jimmy Jam and Terry Lewis Cherelle classic. (Robert Palmer also did a creditable version, but its merit was obscured by the whole mannequin model backup band thing.) Enjoy.

New York City, March 17, 2016

★★★ Morning was bright but not sun-flooded, chilly but no colder than that. By late morning, the sky had burned clear. The sun had still not touched the east side of the avenue on the walk back to school for the half-day pickup. The four-year-old had rolled his pants to the knees. A row of bright ovals, projected down through the top edge of the opera house across the street, followed the course of the sidewalk. Clotted mounds of cumulus formed in the west, and then blurry gray overspread everything. Heavy clouds with shimmering marks of strain in them glowered, then relented. The far distant hills to the northwest were a maybe unprecedented pale lilac, with the white spark of some sunlit building floating on them. It had rained some on the sitter on her way over for the later afternoon, but daylight shone down the subway stairs. The breeze felt more like fall than spring. Again horrible clouds covered everything. Umbrellas were out on the sidewalks and tires left wet stripes behind them in the roadway. For a moment the fluorescent fixtures in the newer 72nd Street control house passed for discolored sunbeams. Two trees on Verdi Square were in bloom, and a few daffodils were up. The real sun was blocks down Broadway, on the bright, debased facade of 2 Columbus Circle.