If You Give A Mouse A Heart Attack

by Peter Wieben

Every year, tens of millions of experiments are performed on living mice, rats, birds, fish, frogs, or invertebrates. Usually, when the test is finished, the animal is killed.

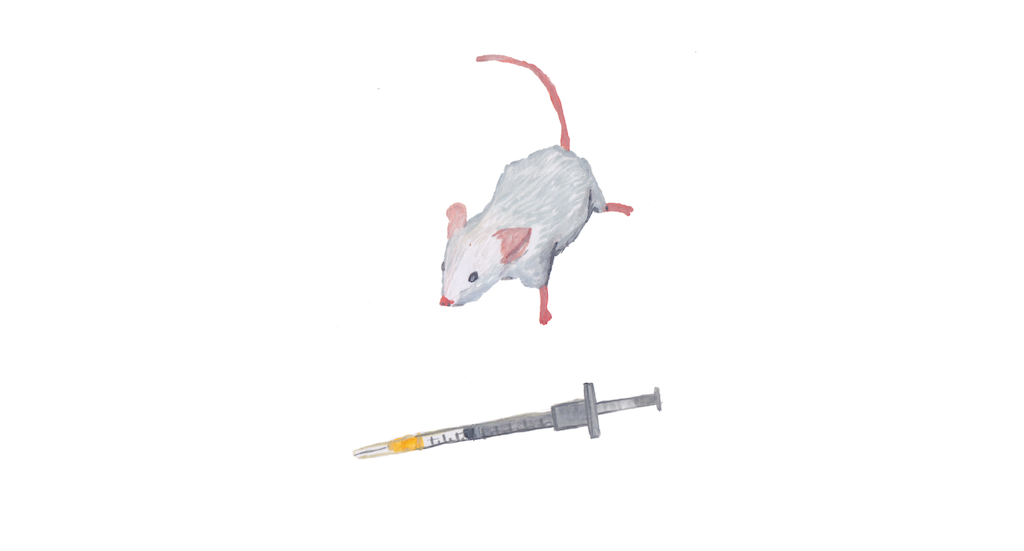

Recently, I was allowed into a secure animal-testing facility on the condition that I not reveal its name or location — the testing is highly controversial — and I witnessed an experiment on a mouse. This particular trial required the scientist to give a mouse a heart attack in order to test a new stem-cell therapy for heart-attack patients. The test I witnessed was a step to determine if further research would be possible; while the scientists have a vision for what they eventually want to understand, no one single experiment is designed to be groundbreaking.

The scientist I met went to work each day and performed a simple heart surgery on mice. He opened up a mouse, and put a thread stitch into its heart. (Typically, a mouse can survive that, and many of them live on after being stitched back together.) In his lab, there were many locked doors, and locked wings of the building. He only had access to areas he needed for his research.

“We’re looking at different things,” he explained. “All of it to do with the heart. Usually, it is to do with stem cells, and whether they can be used to help injured hearts.” He was studying whether the time of day that a heart gets injured could change the way the heart reacted to injury and affect the patient’s recovery.

“So this mouse will help solve that?” I asked him.

“Sort of,” he said. “I want to check on something in the heart. So I am going to mince them up and look at them. I want to find out if its feasible to do the same thing for more mice. It’s a proof of principle.”

On the day I was there, the scientist needed to analyze the mouse’s heart, liver, and spleen. The mouse was eventually going to have to die. Its head would be held in place while its tail was pulled three times in order to break its back.

“That part of it I never got used to,” the scientist told me. “When I have to kill them. That part, I still feel it.”

“It’s routine now,” he said. “Some days, I can do eight surgeries.”

“So, four before lunch and four after?” I asked.

“Something like that,” he said.

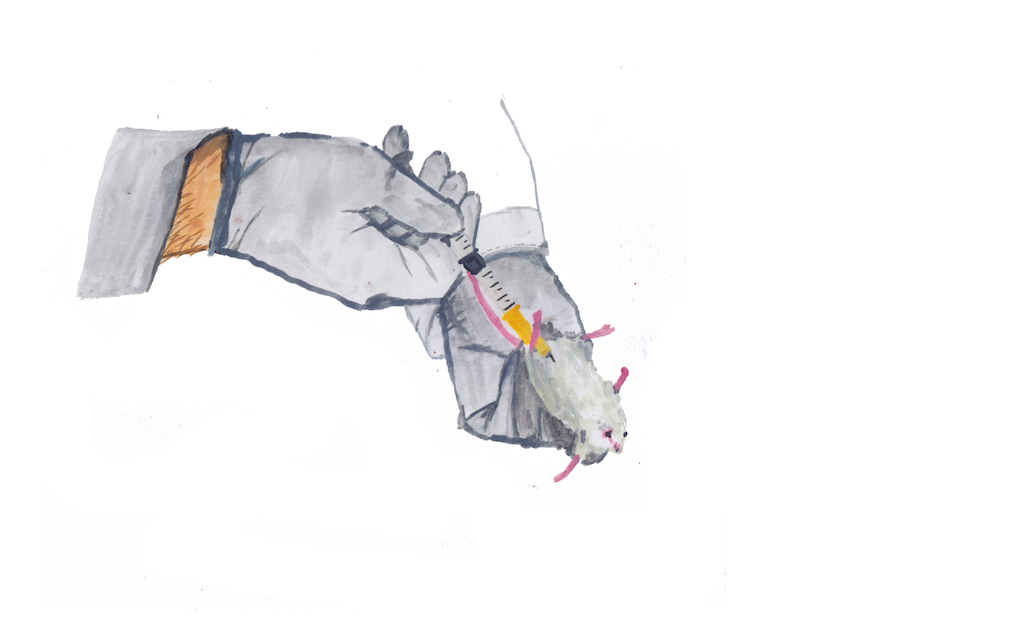

“When I started,” he said, “it was difficult to catch them.” He reached into the cage and took the mouse by its ears. He held it upside-down, and injected something into its stomach. He explained that if he were to do this part wrong, blood could come out, and that it had happened a few times, but now it rarely did.

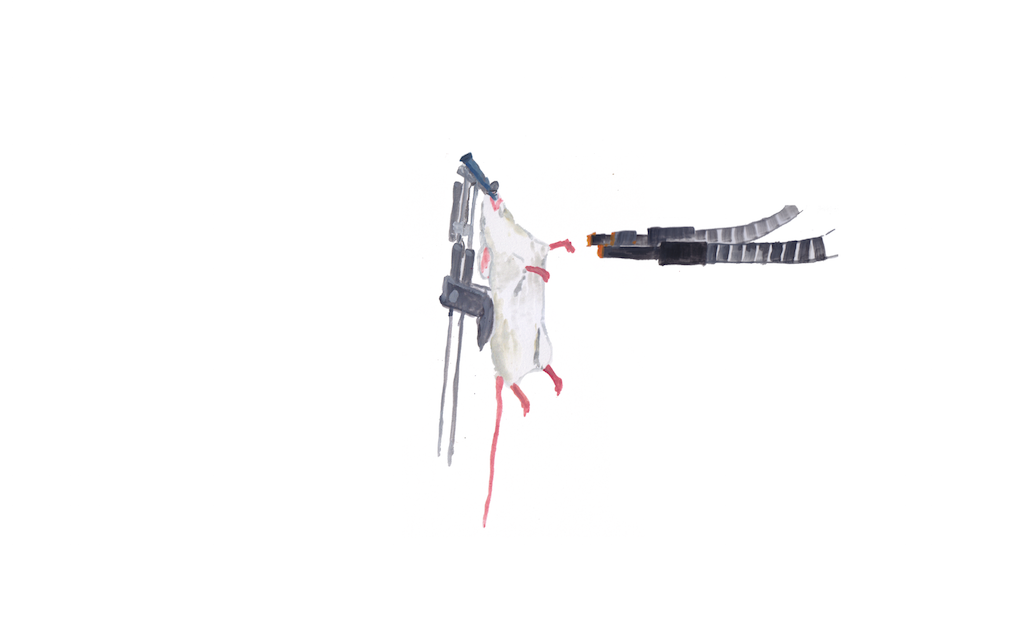

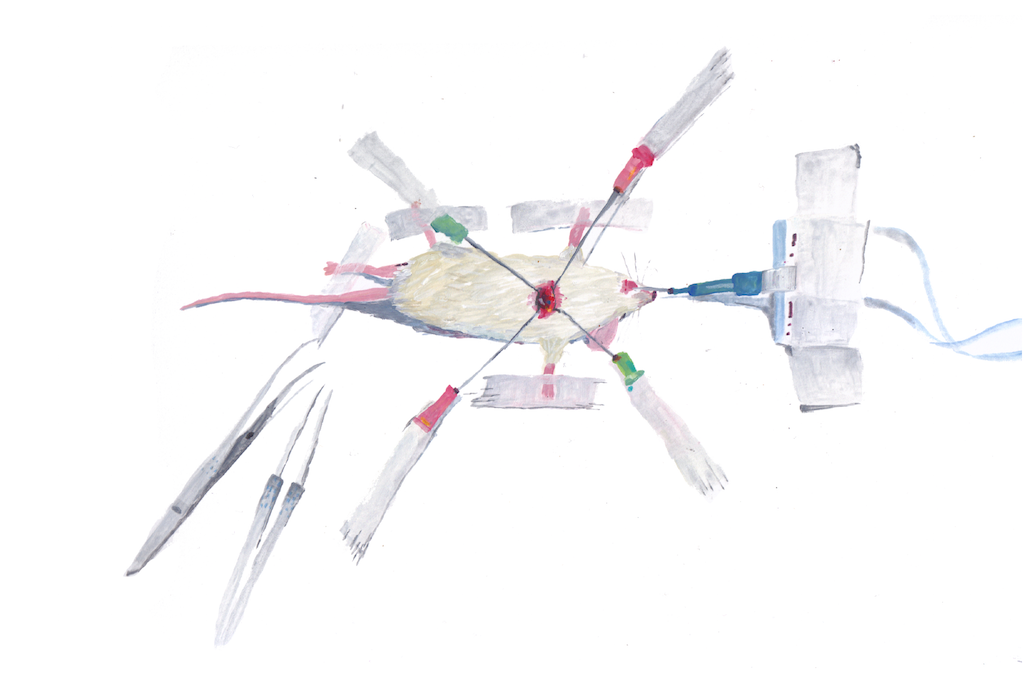

Using a vise-like apparatus he had made himself, he hooked the mouse’s teeth to a string, and pulled it tight — the mouse was held back in position by its teeth. It was unconscious. The scientist used bright lights to see where to put the breathing tube. If it went down the wrong way, the mouse’s stomach could inflate when he turned on the air.

He taped the mouse onto a heating pad. First, he checked that the mouse was breathing. Then he taped one front paw down, and then the other. The mouse’s hind left leg was crossed over its right. This way, when the mouse was fully taped down, its heart would be directly beneath the lights and the microscope, exposed for cutting.

The scientist used hair-removal cream to take the hair off the mouse. He put cream on its eyes, which were still open.

As I watched the scientist and asked him questions, I struggled to avoid calling the mouse “him.” I was embarrassed, because it seemed childish. I tried to call the mouse “the subject” once, but that sounded weird, too.

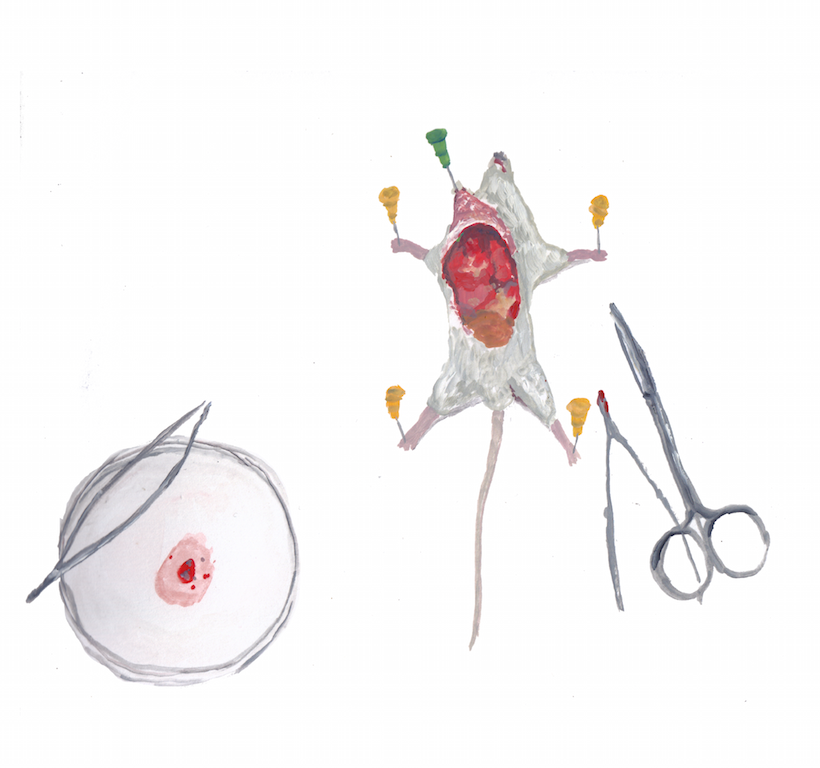

He cut the mouse open, showing me how to move the ribs out of the way and get the muscles to come apart, and how hooks were used to hold the hole open.

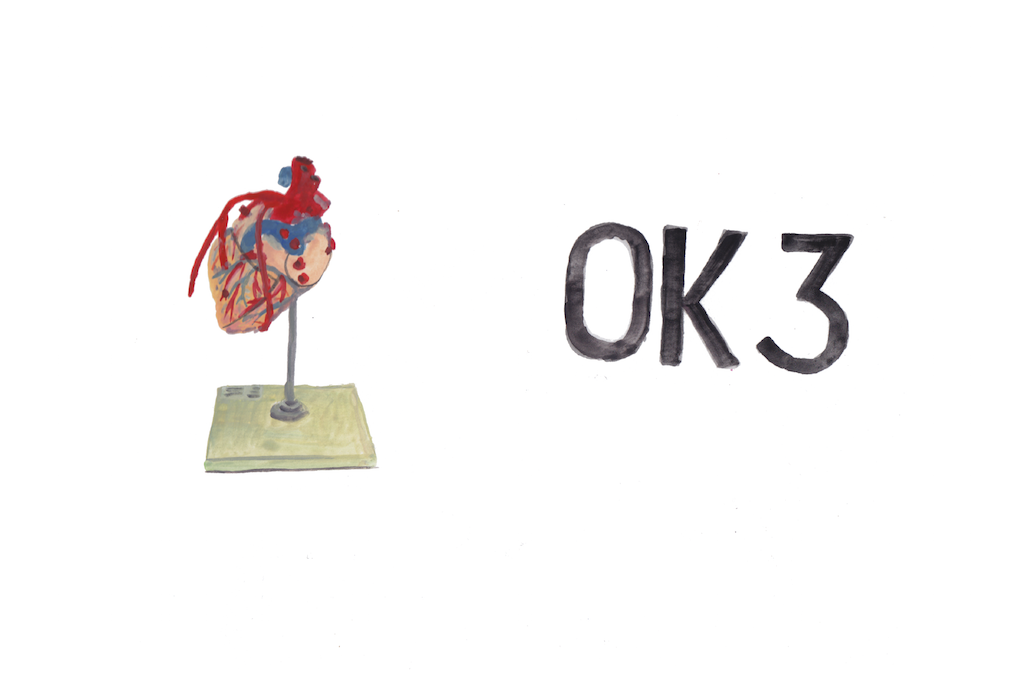

The beating heart was visible once he cut the mouse open. He let me look through the microscope, and showed me that he could push it from side to side if he wanted. He told me that mouse hearts are very strong, and doing this to a human would be extremely dangerous. The heart was the size of a pea. It was red and blue.

Then, he gave the mouse a heart attack.

Then, using a tiny suture, the scientist put a stitch into the coronary artery, and tied a knot in it. After twenty-four hours on painkillers, the scientist told me, this mouse could live a normal mouse life, even with a stitch on its heart. He held it in his hand. It was limp, but still breathing. He turned it onto its stomach, grasped it by the neck, and pulled on the tail, hard. Then again. Then a third time.

Later, the scientist brought me into the room where the mice were kept. “Here is my team,” he said. There was a little family of mice in a box like you would see at a pet store. His mice were all small, white mice. “I like to give them some paper towels. They like them. They tear them up and they can make houses or whatever. It makes them happy,” he said.

Some of the other mice, next to the family, had massive growths. “Tumor mice,” he told me. Others had red signs on their cages, showing that someone witnessed a fight in the cage. Others had a skull and crossbones, indicating toxicity.

Once his mouse was dead, the scientist’s cuts were still somewhat careful, but less precise. He didn’t use any tape. The mouse’s limbs were pinned down, and its body was splayed open. Using scissors, he took out the heart, and put it in a petri dish. “See?” He said. “It keeps beating.” He stirred it with the scalpel, and yes, it was beating.

“How?” I asked him. It was amazing. “Is it still alive?”

“It’s just energy left in the cells,” he said.

“Fifty percent of people don’t believe in animal testing,” he told me. He put a date on a little paper, which was the mouse’s death certificate. He loosely stitched the mouse back together after removing the heart, the spleen, and part of the liver. Each was put into a tiny test tube and sealed. After the weekend, he was going to grind them up to analyze them, testing for levels of enzymes. The result would have a meaning to him, but it was a tiny step in a very long journey.

He put the mouse into a little sandwich bag. It occurred to me how small the mouse was. He walked to the freezer, and told me not to look inside, but I look anyway. Then he put the mouse in, near many others.

Hundreds of experiments like this will be done in order to reach a conclusions about things like about heart-attack timing. Some mice will be given treatments, others will not. The ways their hearts react will be studied across many, many experiments. If they succeed, the trials will be repeated many more times in other labs. Dozens of minor variations will be checked, and hundreds more mice will be be killed, each little life like a drop in a rainstorm.

It was hard not to call the mouse “him” while it was alive.

“He did his duty,” I said.

“He did his duty.” the scientist agreed.

Maybe It Would Be Better If Writers Talked About Themselves A Little Less?

As someone who would be thrilled to live in a world where the only time you saw a capital I in an extended review or piece of reportage — my least favorite thing about journalism is when the writer has to remind you he’s telling you the story, e.g., “I drove over to Anderson’s office later that day and watched him interact with his staff. Everyone seemed happy to have him there, and the work got done quickly.” WHO CARES ABOUT YOU? WHY THE FUCK DO I NEED TO KNOW THAT YOU DROVE THERE? IS THE NEXT PARAGRAPH GOING TO TELL ME HOW YOU FILLED OUT YOUR EXPENSE FORM FOR THE MILEAGE? — was at the beginning of the word “Internet,” I should be completely sympathetic to the argument that “critics need to stop getting personal in their essays,” and for the most part I am. It’s difficult to disagree with this:

Contemporary criticism is positively crowded with first-person pronouns, micro-doses of memoir, brief hits of biography. Critics don’t simply wrestle with their assigned cultural object; they wrestle with themselves, as well.

Unfortunately, my objection isn’t so much to the idea that it’s wrong to use your own experiences as a guide to explain how you interact with the items under review as it is to the fact that so many of the critics who are doing it are boring, grasping people whose experiences are mundane at best and often comically over-inflated given how empty and insignificant they are. Most writers are a seemingly impossible mix of neediness, self-importance and insecurity. It should not be shocking that someone who has decided their expertise is so invaluable that everyone else is waiting for them to weigh in on a subject — these are frequently the kind of people who tell you that they have to write, it’s not a choice or an option for them, it’s something that they must do for they can do no other etc. — would prize the earthshaking events of their own life that helped develop their unique, inestimable voice as highly as (if not more highly than) the ostensible subject which they are using as a jumping-off point to tell you more about themselves, but that doesn’t mean it’s in any way tolerable for the reader unless you are one of the six or seven living writers who can actually pull something like that off. (That number may be high.)

Writers have always been gross egomaniacs but at least in the past we were unaware of the vast majority of “but what I learned that summer’s day in college that relates to this Batman movie” pieces because we were shielded from the gigantic torrent of self-regarding wordflow that was just waiting to burst forth. I think the flaw with this piece isn’t that its argument is unfair to the people who engage in this sort of look-at-me-and-my-deep-deep-feelings criticism, it’s that the proscription against first-person exegesis is too narrow: Let’s get rid of the “I” in fiction and memoir too. If that means no more fiction and memoir, well, it is a small price to pay to make all those people who think they are too highly refined and emotionally gifted stop talking about themselves for just a few minutes, and if you’re going to tell me that I’m using the personal pronoun an awful lot in this piece decrying it, well, oh my God, what an amazing point you raise, I never thought of that. I know I’m talking about myself too much here. I’m a writer, I can’t be anything but gross and self-important. It’s just how we are: showy, self-involved and unwilling to shut up about ourselves. The fact that you’re still reading this is a great indication of how you’ve been trained to believe that this kind of disgusting monology is what you deserve as a reader. Someone should shut us all down, or at least take our I’s away.

Photo: Shutterstock.com

Dorothy Parker's "If Only"s

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=iMnv1XNpuwM

“Dorothy Parker was too smart to buy the legend and too clearheaded to slide into nostalgia. That left her having to acknowledge some bitter realities…. The tragedy of Dorothy Parker, it seems to me, isn’t that she succumbed to alcoholism or died essentially alone. It was that she was too intelligent to believe that she had made the most of herself.”

— If you cannot read enough of or about Dorothy Parker you will want to add this to your list.

A Poem By Linda Besner

by Mark Bibbins, Editor

The Labour of Being Studied in a Free-Love Economy

My daughter celebrates May Day

by ring-rosing a stripper pole.

She’s a herdsman who closed

her eyes in a lemon grove,

woke up in a janitor’s closet.

At the chime of mop o’clock

in the morning metro, here’s Marx

thundering down the ghost hose.

She’s wet with the spittle of the greats.

Cagey as a row of roosters shining

like goth lip gloss at the fair.

Your attention a soiled glove

to pinch the maid’s nose closed.

For professional reasons,

I follow a sad foster kid’s

anonymous blog. She writes:

“This blog is copyrighted.

I know that means you can’t

take my writing without

my permission. If you do,

something can happen.”

All she has is a misery of interest

to sociologists. Her prize

to be here immortalized

in a dying medium. My daughter

is the delicate trickle-down.

The desk-top orchid trembling

in the front office of a firing range.

Dear window-shopper,

your reward is the Pastasaurus

I bought my boyfriend

at the strip club gift shop.

It’s dinosaur spaghetti-tongs.

Water streams out its eyeholes,

noodles swoon from its green jaw.

Forgiveness on its lips on your neck.

Linda Besner’s first book of poetry, The Id Kid, was published in 2011 by Véhicule Press and named as one of The National Post’s Best Poetry Books of the Year. Her second, Feel Happier in Nine Seconds, will be published in 2017 by Coach House Books. She lives in Montreal.

Allen Toussaint, "Big Chief"

Stereogum notes that the New Orleans classic “Big Chief,” performed here by the late Allen Toussaint on his forthcoming final album, was “sampled in a Lily Allen song.” At first I was horrified by the idea that anyone under 30 might only know this iconic piano roll through “Knock ’Em Out,” but then I realized that people under 30 probably don’t even have much of an idea of who Lily Allen is at this point. It’s time to die, is what I’m saying. Anyway, please enjoy Allen Toussaint’s take on “Big Chief.” I’ll be sitting quietly in the corner, remember what life was like during the Roosevelt administration. You wouldn’t believe what a nickel would buy you back then.

New York City, April 12, 2016

★★★ The sloshing of the wet city reached the addled brain in its sickbed. Then for a while came drops hitting the window. Later, considerably later, a line of pale blue appeared just over the top of the apartment slab to the west. A whole new sky came on, inviting and possibly tonic. Downstairs some petals blew loose along the bricks; some petals stuck to the puddles there. Teal blue plastic outdoor chairs were stacked outside the hardware store. A newsstand clerk burst out of his shelter to shout and point at a young man making a getaway, moving just slowly enough to swagger. There were no clouds to catch the sunset but fleetingly gold glowed off the underside of the rotor of a passing helicopter.

A Twee Throws In Brooklyn

“An annual competition to see who can hurl a banjo farthest into the Gowanus Canal came un-strung on Sunday afternoon, after neighbors called the cops, and the five-stringed instrument then hit a tree and broke free from its tether, floating off into Brooklyn’s Nautical Purgatory. The snafu brought the contest to an abrupt end, but an organizer said all the drama made it one for the books.”

Streams Gush

“In the age of binge-watching, there is unending faith that consumers who already may pay for some combination of Netflix, Amazon, Hulu and ordinary cable will open their wallets further for esoteric fare like “Lather Fantasies,” a $20-a-month service founded by a Tampa Bay businessman that shows clothed people excessively shampooing each other’s hair.”

'Hamilton' Bad For Women

Sorry, ladies, looks like you might throw away your shot to be on the front of currency. I hope for your sake the forthcoming musical Hickory — replete as it is with dazzling wordplay such as “I’m rappin’ Andy Jackson and I’m here to say we’ve got to withdraw federal deposits from the Bank today” — doesn’t remove other bills from potential revision.

Postcard From Malheur

by Scott Latta

In the ornithologist’s lexicon, there are twitchers, and there are dudes. Twitchers are the hardest of hardcore birders. Myopic. Obsessive. Romantic. “Twitchers,” one birding forum says, “might cross half the country overnight to see one tatty brown thing sitting half a mile away on a bleak expanse of mud.” Even among birders they’re rare. Having recently returned from The Harney County Migratory Bird Festival, essentially the Bonnaroo of birding in Oregon, I can recall meeting only two. The first was a woman I passed on a dirt road, staring tenderly into an open field. I could tell she had spotted something beautiful, so I followed her sight line. The field was empty. The second was a man I saw standing outside a high school, his hands curled lovingly around his mouth, making goose sounds up into the sky.

Those of us comprising the other end of the spectrum (despite that women make up the majority of birders in this country) are the “dudes,” a slightly derogatory label for those who could never spot a black-bellied whistler from a fulvous whistler, but who can just about tell you a duck from a goose. In the dusty lonesome exile that is southeastern Oregon, for a few weeks every year, there is a type of Ornothologia grossus for the dudes, when the spring migration along the Pacific Flyway brings millions of arctic birds home from Patagonia, right over the town of Burns, where they stop for a bit in Oregon’s Malheur National Wildlife Refuge. There I went, a dude among the twitchers, to see what a million birds looks like. It was also there, three months ago, that a group of political extremists bearing assault weapons broke into the Refuge and stayed for forty-one days.

Burns is the largest city in Harney County, Oregon, which itself is larger than six U.S. states. That doesn’t mean much; cattle outnumber people there by a factor of 14. The city is so deep into southeast Oregon that I would say it’s basically in Idaho, but it’s still 133 miles from Idaho. It’s the part of the West where things are so far away that they reset your idea of what far away means. I’ve put off friends because a restaurant was two miles from my house; people go fifty miles to split the difference there. It’s so remote that the man who checked me in at the Silver Spur Motel described what he was doing there as “hiding out” (I didn’t press). Burns feels more like an outpost than anything.

The word I heard most often in stories about the Refuge was “occupation,” a word with more than one layer. There was the occupation of Malheur Refuge, which the country watched for six weeks with a sort of curious bewilderment. But there was also the occupation of Burns, which started earlier and felt more personal. For weeks leading up to the Refuge occupation, hundreds of members of various western militias moved into Burns. They came to support Dwight and Steven Hammond, two local ranchers who were about to go to jail for burning federal land. They took up residence and made themselves visible, threatening people who felt differently. They stalked the sheriff’s elderly parents home from a yard sale. All of them — wherever they were, at every single moment of the day — carried guns, especially to the public forums where residents suggested they go home so their kids could go back to school. Few of them, however, actually went on to the Refuge. The taking of Malheur was a fringe-y political exhibition of states’ rights that never had a chance. But the occupation of Burns took over a city.

I went, as John James Audubon put it, to exchange “the pleasure of studying men for that of admiring the feathered race.” In other words, I wanted to see some serious birds. Days before my arrival, a nice lady from the Chamber of Commerce told me over the phone about a place called Hotchkiss Lane. “Have you seen the video?” she asked. She meant the clip from Oregon Public Broadcasting where a blizzard of snow geese takes off all at once in this awesome goosey dervish. You bet I’d seen it. Three days later my wife Jess and I were there at seven on the dot, blowing into our hands and making bird jokes.

It’s peculiar, but the migration is a huge part of Burns. People get very excited — the lot at the Silver Spur was so full I had to park across the street. This year’s festival was the town’s thirty-fifth, a big year made even bigger by the subtext: It was the first chance for Burns to be its old self again, to forget those six weeks and just be a place where a man can make goose calls outside a high school. On our first drive out to Hotchkiss, we passed a farm that appeared to be growing huge rows of cotton in the backyard. Snow geese were all pressed together inside the chain-link fence. The farm looked out of place: why had this person put a house where all these geese wanted to be? We pulled off to the side of the road and just watched for a while. It ended up being a solid, if not spectacular first morning of birding — a few impressive flocks milling about in distant fields — striking, even meaningful, though not quite the O.P.B. video.

The only sign something had happened in Burns was a row of orange ribbons tied to the streetlamps downtown. I first noticed them on the way to breakfast; they struck me as sad in that neglected symbolic way, like white crosses on the side of the road. A waitress at The Apple Peddler told me the ribbons were for “togetherness.” I pondered it for a minute, then asked if she was glad everyone had gone. Her eyes widened and she began to nod. “Oh yeah. Definitely,” she said, punching that last word as I took the receipt. In the parking lot, Jess was laughing as she got in the car. “There are two bullet casings by our tire,” she said.

For the duration of the festival, Burns High School served as Bird Central. Student bird art covered the walls, tacked with red and blue ribbons. When we got there, an arts-and-crafts fair was just opening up in the gymnasium; I bought some bookmarks and a red-winged blackbird ornament from a Paiute woman. A group called Friends of the Refuge had set up a table in the back corner, where a woman named Alice was fielding questions. She smiled kindly at me as I approached, a smile that knew exactly what kind of things I was about to ask.

“It was terrible,” she said, barely above a whisper, looking down at her hands. But then she looked up and found her voice, rousing herself into a pep talk. “Actually — our work is just beginning,” she said. She wasn’t talking to me. She wasn’t even really looking at me. “This was a bigger movement against all federal lands in the West. All public lands. Every nation envies our public lands. We have to protect that.”

Afterward, we took one more drive out to Hotchkiss Lane, but every field was empty. The O.P.B.-levels of snow geese, if they were ever there, were gone. Scattered pintails dotted empty fields. It was over for the day. I idled at a stop sign — it was quiet and we were the only car. Suddenly, a cloud lowered in the distance. “There,” Jess said. I gunned the engine.

A half-mile ahead, a squall of snow geese screamed over the fields. The sky was moving with geese. Layers of geese, flanks of geese, V’s in every font — all of it. I skidded into the gravel beneath them. Goose shadows strobed over the pavement; it looked like V-J Day in Tokyo Bay. I have no idea how many birds there were. Ten thousand? Two-hundred thousand? It didn’t matter.

Earlier that morning, on our first trip out to the fields, I thought about what could lead a person to occupy something, to take it over. Cliven Bundy started a standoff in Nevada two years ago over land rights and what he saw as federal government overreach; now his sons and their militias had done just the same at Malheur. Dwight and Steven Hammond were about to go to jail over a land dispute; I wondered what it was about being so close to nature that made us want to control it. I spent a while looking out over the fields, wishing those early geese would all fly away. I was chasing the image from the video. Jess kindly suggested that something might come along and spook them a little for my benefit. “Maybe a car will backfire,” she said. I nodded, then the words slipped out of my mouth before I could catch them. “I wish I had a gun.”

Photos: Jess Latta