Fotomachine, "Patterns"

Let’s just get out of this week with the minimum level of fuss necessary, okay? Okay.

New York City, April 20, 2016

★★★★ Sunbursts filled windshield after windshield. The green had claimed new blocks and was starting in on others. Behind construction fencing, dandelions were tall and bright. The preschoolers, dismissed, didn’t want to leave the playground equipment. The wind stole napkins from a customer at the pastry stand by the subway entrance. Fire escape shadows were tangled with carved palm fronds. Suddenly the air conditioning on the train was obtrusive, swiping down at the hair. Birdsong from somewhere uncertain filled the width of Broadway.

At The Liberation Seder

by Noah Kulwin

Early last week, the Bernie Sanders campaign announced it had hired a new director of Jewish outreach: twenty-five-year-old Simone Zimmerman*, an outspoken lefty activist with and a long history of work within the American Jewish community. Shortly thereafter, the Washington Free Beacon published a screenshot of a year-old Facebook post in which Zimmerman called the right-wing Israeli Prime Minister Bibi Netanyahu “an arrogant, deceptive, cynical, manipulative asshole,” among other not-so-niceties. Abe Foxman, the retired director of the Anti-Defamation League (ADL), called for her immediate dismissal. Thursday night, shortly before the Democratic debate between Sanders and Hillary Clinton got underway in New York, the New York Times reported that Zimmerman had been suspended. The incident looks now like it was a two-day blip on the radar of a year-long Democratic primary battle. In the context of the overlong, meme-ridden 2016 election, that’s fair.

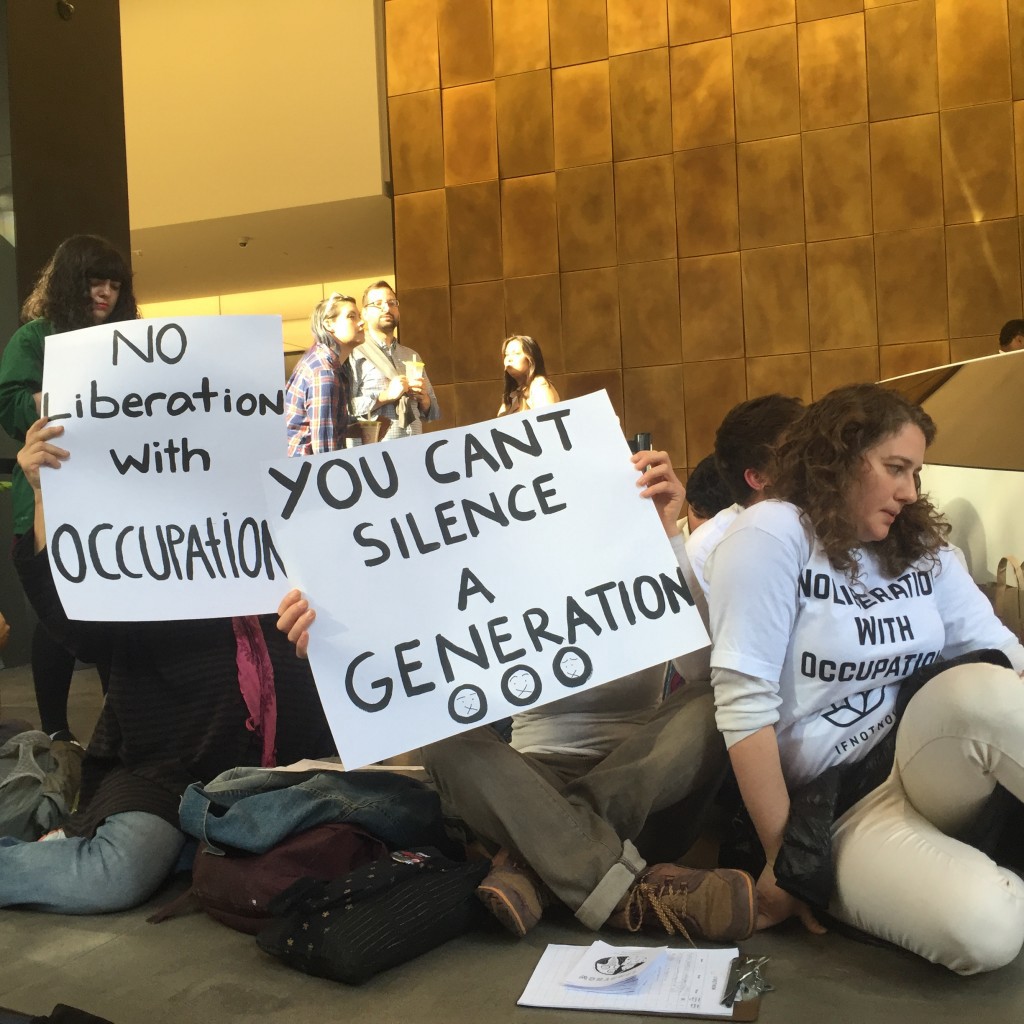

On Wednesday evening, seventeen young, left-leaning Jews got themselves arrested in the lobby of the Manhattan building that is home to the ADL office. They were members of a Jewish anti-occupation collective called IfNotNow, whose name is a reference to a proverb of the Jewish sage Hillel: “If I am not for myself who is for me? And being for my own self, what am ‘I’? And if not now, when?” Virtually all its members were raised in the Jewish community, and many spent time in Israel on study-abroad programs, synagogue tours or trips for Jewish youth. Many speak Hebrew or Yiddish. Simone Zimmerman is a member.

IfNotNow emerged in the summer of 2014, during the last round of intense conflict between Hamas militants and the Israeli military, a devastating war that left more than two thousand Gazans, including hundreds of children, and seventy Israelis dead. Outraged by the American Jewish establishment’s reflexive defense of Israeli military action, the group then staged a sit-in at the offices of the Conference of Presidents of Major American Jewish Organization.

Ahead of this weekend’s Passover celebration, IfNotNow held “Liberation Seder” protests in five cities (New York, Chicago, Boston, Oakland and Washington). Their goal was to use civil disobedience to apply pressure to major American Jewish institutions — Hillel International in Washington, an AIPAC office in Boston — to question how military occupation can be reconciled with values of social justice and equality.

4:00: About forty people gathered at the northwest corner of Fifth Avenue and 40th Street, just outside the entrance of the New York Public Library. Most of them were dressed in white, per instructions. Organizers handed out t-shirts that read “No Liberation With Occupation” to protesters who planned to be arrested.

The group comprised mostly twentysomething Jews, many of whom grew up attending the same day schools, summer camps and synagogues. There were more women than men present, and a handful of yarmulkes (on both men and women).

4:15: Ben Wolcott, a bearded twenty-five-year-old Maryland native who now lives in Crown Heights planned to get arrested (he succeeded). He wore a patchwork sweater that he later swapped out for a “No Liberation” shirt. Wolcott said he spent fourteen years in the Labor Zionist Jewish youth movement, Habonim Dror. After high school, he spent nine months in Israel, an experience that he says “politicized” him, forcing him to “witness occupation firsthand.”

After graduating from Swarthmore, he joined IfNotNow, which he said had reinvigorated his interest in Jewish causes. “I haven’t felt moved by my Jewishness… this is the first time I’ve been excited in many years,” he said, his voice rising. “This is a Jewish space that lives up to the values that I was taught as a kid.”

4:30: The event planners, Tom Corcoran and Lizzie Horne, stood on the steps of the library, and called the growing crowd to attention. They asked people to take a moment “to ground themselves.”

“This marks the beginning of Passover. This proves as a community, as IfNotNow, we say ‘Dayenu!” (or, enough), Corcoran said. “For too many years, Jews around the world have celebrated our own freedom while denying it to the Palestinian people.

He went on, “And what we’re going to do now is march down to the ADL, and take over that space, as a community. A radical, loving liberation seder.”

4:45: The crowd begins the walk over to the ADL, a few blocks southeast of the Library. Avner Gvaryahu, an ex-I.D.F. paratrooper studying for a master’s degree in human rights at Columbia, told me, “there are people in Israel who are following IfNotNow and what’s going here, and they’re hopeful.” Back in Israel, Gvaryahu lead tours in the occupied city of Hebron, parts of which are off-limits to Palestinians. It is a deeply violent place — late last year, the Guardian called it a “pressure cooker” and “the West Bank’s most troubled city.”

5:00: The lobby of 605 Third Avenue looked like any other in a high-priced midtown office complex: high ceilings, revolving doors, keycard access turnstiles, and stocky security guards. The protesters quickly formed a large oval in the lobby, careful to avoid blocking the entrances and exits. They set down a mock Seder plate with drawings of the shankbone, bitter root and other Passover ritual items, and began a series of readings about Jewish obligations to social justice. There were several back-and-forth chants of “Dayenu.”

“This is an institution that ought to belong to us,” one protester said. “Let’s make it a little bit harder for the ADL to keep doing what it’s doing!”

5:15: The protesters linked arms and began chanting classic songs of the American Left (“Which Side Are You On?”) and Passover hymns (“Avadim Hayinu,” or “We Were Slaves”), dancing around the lobby. An older man on his way out of the building stopped to ask an IfNotNow member about the protest. Holding up a phone with stickers identifying him as both Jewish and an alumnus of GWU, he asked if the demonstration was “pro-Israel or anti-Israel.”

“It’s against the occupation of the West Bank.”

“So it’s anti-Israel.”

“No, it’s — ”

“So you’re a left-wing, communist pinko. You’re full of shit,” he said, backing toward one of the revolving door exits. As he walked out, he did not break eye contact with demonstrators, pointing violently and mouthing “You’re full of shit.”

5:33: The first police officers showed up, from the nearby Seventeenth Precinct. Over the next twenty minutes, designated liaisons to the police informed the officers of who planned on being arrested. About a dozen cops stood outside the entrance.

5:50: The police count increased and those planning to be arrested hugged their comrades. They sat down, linked arms and began chanting. The crowd, by that point between 90 and 100 people, exited the lobby and began chanting in solidarity.

5:52:

.@IfNotNowOrg, there’s more we agree on than disagree on.

Let’s talk about it. When are you free?

— ADL (@ADL_National) April 20, 2016

6:04: The Strategic Response Group, NYPD Commissioner Bill Bratton’s trained “protest police,” began arriving. The arresting officers were identifiable by the bundles of zip-ties attached to their belts.

6:15: Toby Irving, whose job was to stand outside the building during the demonstration and field questions from passersby, told me that her job was mostly fine, except for one guy who came up and asked her what the protest was about. She “I said it was against the occupation. He asked, ‘Occupation of what?’ I said, ‘the West Bank.’ And then he looked at me and said, ‘Fuck you, you fucking bitch.”

6:20: Arrests began. The activists formed a set of two Red-Rover-like lines, creating a path between an exit of the building and one of the vans they would use to take the arrested protesters to jail. The SRG officers zip-tied the hands of seventeen demonstrators and walked them through the two lines and into the paddy wagon. As the arrested demonstrators were marched to the vans, the IfNotNow activists began chanting the Jewish hymn, “Hine Mah Tov”:

Behold, how good

and how pleasant it is

for brothers to sit together.

As the protest wound down, a voice in the crowd shouted: “We told them we were free, when they supported freedom and dignity for all Palestinians.”

6:36: The vans with the arrested protesters drove away.

Tfw you’re in the back of a NYPD van trying to start a movement against the establishment’s support for occupation pic.twitter.com/FRoV3tSBDZ — IfNotNow (@IfNotNowOrg) April 20, 2016

*Disclosure: When I was at U.C. Berkeley, I and a group of others that included Zimmerman co-founded the school’s chapter of J Street U, the student organizing arm of the center-left political advocacy group J Street. The year after Zimmerman served as president of the J Street U National Board, I served as the board’s West Coast Representative. I have known many of the people in this story for years. I have not been associated with J Street since finishing my term in 2014, and I have not worked with Zimmerman or anyone else in this story since then.

Expecto Paternus

by Josephine Livingstone

The Archbishop of Canterbury’s website is coded a restful purple, soothing to those in need. The layout is basic, but in the top right-hand corner there is a box. SEARCH, it says. ADVANCED SEARCH, reads the option below. Alas, there was no advanced search needed for those looking to discover the true paternity of the Archbishop of Canterbury, Justin Welby, earlier this month. In a statement issued by the Church of England on April 8 in response to pressure from the media, the Archbishop revealed that his biological father was not whisky salesman Gavin Welby “but, in fact, the late Sir Anthony Montague Browne. This comes as a complete surprise.”

I was at work when my phone buzzed. My parents live in England, and they don’t ring me up at unexpected times. Buzz buzz! It was my dad, trying to find out whether Americans knew the name of the celebrity protected by the high court’s super-injunction. I hung up. Buzz buzz, again! This time it was my mum. Could it be that she, too, was hunting the identity of the super-injunctioned celebrity? Disappointing, if so. But no: “I’m sorry I couldn’t ring earlier,” she said. “The Archbishop of Canterbury has turned out to be illegitimate and Granny is very, very upset.”

For people of my grandmother’s generation, this is a scandal of unbelievable proportions. High-ranking clergy, the royal family, and the aristocratic political dynasties of Britain aren’t just meaningful for her. They’re Michael Jackson-level famous — so distant from her ordinary life that they might as well be creatures of a different species.

Though the younger generation doesn’t give two hoots about the Church, the papers spun this story into real news. If you’re not British, you may not be familiar with the torrential attentions paid by the tabloids to every move and machination made by this slice of old-school British society. They report on the university antics of children of the gentry like the Post reports on fringe Kardashian players. But news it was, and the story came from the Telegraph, the conservative but legitimate-ish newspaper. The paper was proud of having “pieced together the evidence” (which seems to have its roots in longstanding rumor) and then having taken that evidence to the Archbishop. They got him to do a DNA test. In the article announcing their findings, we can see a photograph of the hairbrush that provided the key evidence, captioned “Hairbrush of Anthony Montague Browne.”

Nobody apart from Archbishop Welby seems terribly interested in his mother, Jane. She used to be an alcoholic. She married again, and now holds the rather good title Lady William of Elvers. The news seemed as much a shock to her as to anybody. She told the Telegraph that her relations with Sir Anthony were “fuelled by a large amount of alcohol on both sides.” She raised the Archbishop chaotically, but he stressed in his official statement that he is very proud of his mother’s recovery. When the Daily Mail re-reported her comment, they took out the “on both sides” part, making it sound like she was the drunken initiator. Sir Anthony and Jane slept together “in the days leading up to [Jane’s] very sudden marriage” to Gavin Welby, the man the Archbishop still calls his father.

Sir Anthony, however, was an Important Man. He was of a notable military family, himself earning distinction as a pilot in the Royal Air Force during World War II. He went to work for Winston Churchill in 1952, and remained in his employ until Churchill’s death in 1965. Like Justin Welby, he had mournful eyes under sensitive eyebrows, set in a medium-nice face. According to the Telegraph, Sir Anthony had hinted to his wife over the years that he had a son. But he confirmed the fact to a stepson “when he was shown a picture” of Welby in, conveniently enough, “the Telegraph.” The Telegraph also reported that Sir Anthony and his stepson “spoke in French to avoid being overheard.”

Sir Anthony was part of a scene of power that is interesting to precisely the same generation of British people that cares about whether or not the Archbishop of Canterbury is illegitimate or not. But the Archbishop himself has a bit of a target painted on his back: in 2013, he himself got into a slight media pickle. Archbishop Welby naturally cares a lot about poverty and the lives of ordinary people, so he came out against high-interest loan providers, specifically a company called Wonga (British slang for cash). Wonga advertised to the vulnerable, he said, and “once the loan has been taken out, it is difficult to get out of the cycle.” This is true, of course, but it also happened that the Church of England was financially connected not merely to moneylending, but to Wonga itself (a venture capital firm controlling Church money had invested in it).

Aside from the Wonga snag, Justin Welby has been a pretty good Archbishop. He strongly supports women in the Anglican Church and thinks they should be eligible for consecration as bishops. He does not like Islamophobes and he encouraged the people of Britain to care for rather than fear asylum seekers. He speaks French and likes France. I read on his Wikipedia page that when he was appointed to an earlier bishopric, he said in his speech that his hobbies were “most things French and sailing.”

So, a nice man has been embroiled in scandal here. Or, rather, a sad story has been thrust upon him, but one with a happy ending. Archbishop Welby’s parents raised him drunk: he spoke publicly once about a Christmas day he spent hungry and alone. This change in paternity is clearly a great shock, but not, one gets the feeling, the least likely thing ever to have happened.

The Archbishop of Canterbury hasn’t been plunged into crisis, however, because the kind of man who becomes Archbishop of Canterbury has to be made of very stern spiritual stuff indeed. After that push from the Telegraph, Archbishop’s Welby’s public statement makes it clear that, for him, this is really a story about God’s grace:

Although there are elements of sadness, and even tragedy in my father’s (Gavin Welby’s) case, this is a story of redemption and hope from a place of tumultuous difficulty and near despair in several lives. It is a testimony to the grace and power of Christ to liberate and redeem us, grace and power which is offered to every human being.

My grandmother was a nurse in the war, in London. She’s lived a difficult life. She believes in God, even though he has been kind to her in fits and starts only. Has this scandal shaken her belief in a beloved establishment, or does my grandmother perhaps see a little more humanity flowing through her idols? I cannot know. I was going to interview her for this piece, but I didn’t want to make it seem like the way she felt was funny. The associates of Winston Churchill and the Archbishop of Canterbury are not people she wants to see knocked off their pedestals, and I can respect her reasons for that. I suspect that, beneath her outrage, she might be enjoying the whole thing just a tiny bit. But you’d never know it to hear her — she’ll only let on to being very, very upset.

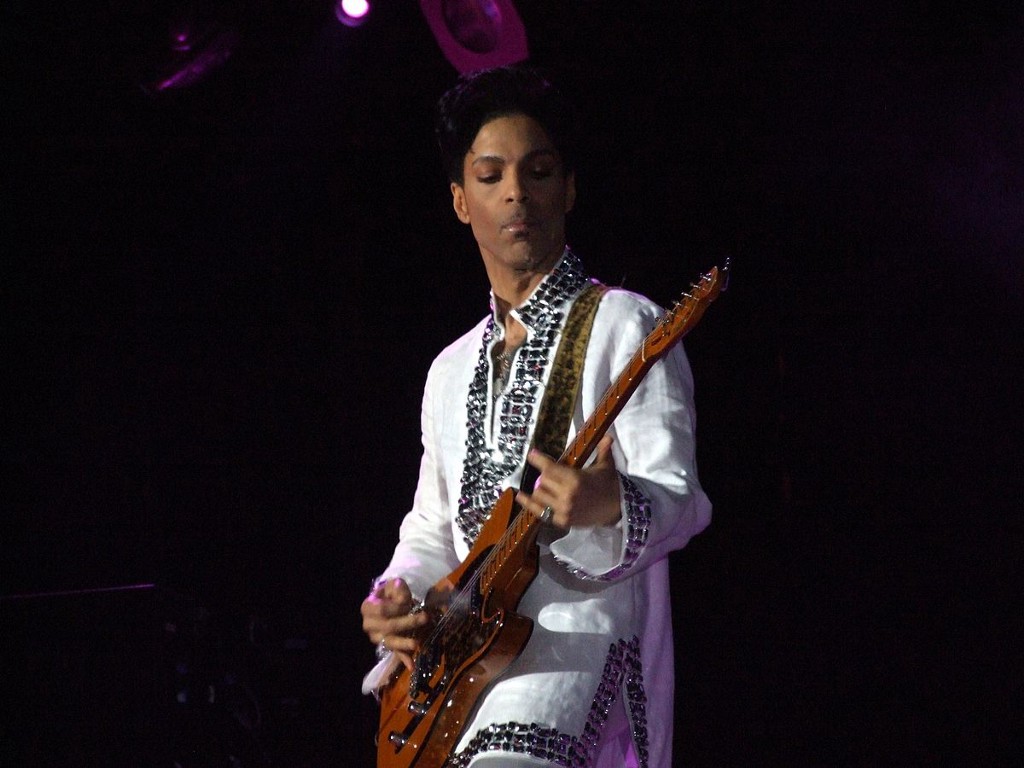

Prince, 1958-2016

The AP has confirmed that “Prince has died at his home in suburban Minneapolis” this morning. He was 57, and a talent beyond words.

Photo:Penner

He-Who-Must-Not-Be-Named

by Emma Garman

In the globalized digital age, attempting to suppress a faintly titillating story is tantamount to launching a multi-pronged campaign to publicize it, only more humiliating. Troubled times, then, for UK celebrities with peccadilloes they’d like to shield from the nation’s eyeballs, as the international media frenzy over a famous husband’s classified threesome proves that, more often than not, obtaining a press injunction is an obscene waste of money. In the US, the idea of muzzling the press is, of course, constitutionally anathema, and would be considered prior restraint. Not so across the pond, where since around the turn of the century, a quirk of law has meant that anyone with sufficient means can, by making a legal claim of privacy invasion, kill an embarrassing or damaging article before it is published. But, to quote neuroscientist Dean Burnett, “if people are aware that something is kept from them, they will be considerably more motivated to actually see it.” And seeing it, whatever it is, hardly presents a challenge when the crowdsourcing of information online is so effective, not to mention essentially lawless.

Nonetheless, the declarations that emblazon the websites of Britain’s leading “reputation management” law firms are as confident as ever. “DEFENDING REPUTATION, DEMANDING PRIVACY” yells the home page of celebrity-injunction pioneer Schillings, while Carter-Ruck — whose endeavors to prevent people in England and Wales from hearing about that threesome were of barely any avail — touts “a discreet service to protect our clients against the publication of intrusive information about their private and family lives.” Perhaps the Carter-Ruck legal eagles who agreed to seek this now-legendary gag order were too dazzled by innumerable billable hours to remember that, what with the invention of the internet, “intrusive information” is not restricted by geographical borders. Otherwise, it’s difficult to imagine how anyone — let alone an expert in the field of privacy law — could not have foreseen the whole affair unfolding precisely as it did. Rarely has the Streisand Effect manifested more powerfully, yet predictably.

When a celebrity pays to keep something out of the public domain, onlookers’ motivations are fueled by more than mere curiosity. A survey of the current debate elicits comments along the lines of: I don’t care about a consenting adult’s sex life, so would have paid no attention to this story, but I do care about preserving an unfettered press/about unelected judges wielding excessive power/about the wealthy denying free speech to their poorer fellow citizens/about a tiny elite having access to legal protections unavailable to the vast majority (the cost of bringing an injunction, after all, can run into hundreds of thousands of pounds).

A key facet of the debacle is that, contrary to some reports, Carter-Ruck’s client did not obtain a super-injunction — which, as well as barring the publication of the names and details of a given case, bars the very fact of its existence being reported — but an anonymized injunction. This allows the general outlines of a gag order to be written about with names removed, leading with swift inevitability to everyone’s favorite Twitter game: Name That Celebrity. The mainstream media, meanwhile, will have fun by conspicuously writing about the relevant personages in other, non-litigated contexts. Venerable gossip site Popbitch — itself the proud recipient of a stern letter from Carter-Ruck — has provided this invaluable guide to the clue-dropping techniques of journalists. “Nothing,” they observe, “brings the brotherhood of journalism together quite like a celebrity injunction. Especially as a whodunnit story is likely to up your own page views off the back of one of your rival’s legal bills.”

The term super-injunction was first used by the Guardian, in October 2009, to describe the draconian suppression of their investigation into Dutch oil trader Trafigura’s toxic waste dumping in Abidjan in Ivory Coast, a catastrophe that caused sickness, injury, and death in the local population. The legal action — brought by Carter-Ruck on behalf of Trafigura — was anonymously named, the court documents were sealed, and the Guardian was forbidden from publishing a single word about it. It was thanks to Labour MP Paul Farrelly that the newspaper was ultimately unshackled: using his parliamentary privilege, which confers exemption from prosecution, he raised the matter of the injunction in the House of Commons. #Trafigura immediately began trending on Twitter, and following a huge public outcry, the company was forced to back down.

Super-injunctions have become much harder to procure since their heyday in the late 2000s, when they were “thrown around like confetti.” In the first nine months of 2009 the Guardian was served with “at least 12 notices of injunctions that could not be reported,” and the tabloids were receiving many times that number. By definition, we can only know the particulars of these injunctions if the claimants themselves chose to reveal them — which has occasionally happened — or if they were overturned at a subsequent court hearing. Such was the fate of footballer John Terry, then the captain of Chelsea FC and the England team. In January 2010, the High Court granted a temporary super-injunction to block the reporting of Terry’s extra-marital affair with Vanessa Perroncel, a French lingerie model and the former girlfriend of a close friend and teammate. But just a week later, the judge lifted the injunction and suggested that Terry — whose £7 million-a-year salary was supplemented by millions more in brand endorsements — did not so much dread the violation of his privacy as the harming of his sponsorship deals.

Alas, the potential injury to one’s wallet from a front page exposé does not constitute legal grounds for said story to be quashed. Once was the time that press injunctions were only issued when the reporting of a particular court case might endanger someone’s life, or to avoid prejudicing a trial, or to safeguard the identities of children. Their specific use by VIPs with naughty secrets has its provenance in 1998, when Prime Minister Tony Blair introduced into English law the Human Rights Act, which enshrines the right to a private life. The architects of the original European Convention on Human Rights, drawn up in 1950, intended to prohibit the type of oppressive state intrusion into personal affairs seen under Fascism and Communism. The notion of helping overpaid priapic athletes conceal their infidelities with breasty young women had, no doubt, not even flashed through their minds.

That arguable blot on our history reached its nadir in May of 2011, when Manchester United’s Ryan Giggs obtained an anonymized injunction against reality star Imogen Thomas, with whom he’d had a seven-month affair. His anonymity was quickly blown by foreign publications and on social media. Giggs doubled down and sued Twitter in a vain effort to obtain the names of all the tweeters who’d flouted the injunction. (“You would have to be a moron in a hurry,” retorted media lawyer Mark Stephens, “to suggest to this footballer that he throw good money and publicly excoriate himself yet further.”) In response, Liberal Democrat MP John Hemmings opined during a Commons question on privacy orders that “with about 75,000 people having named Ryan Giggs it is obviously impracticable to imprison them all.” Since reporting the proceedings of Parliament has been an inalienable right for centuries, the injunction was instantly rendered null and void.

In the same month, a Committee on Super-Injunctions — a group of lawyers and judges who participated in a year-long inquiry — advised that in the recent past, super-injunctions “were being applied for and granted far too readily” and that judges ought to carefully weigh the right of privacy against the right to freedom of expression. In fact, this was simply a reiteration of the government’s instructions when the Human Rights Act became law; then, the courts were told to give particular emphasis to the importance of free speech, and public interest, when considering injunctions.

In the late summer of 2010 — which saw, in the space of a few weeks, three of the England team divulge their sexual escapades to the courts so that we might remain innocent of them — the pendulum had indeed swung pretty far the other way. It is, of course, down to a judge’s discretion whether a claimant’s entitlement to secrecy trumps both the defendant’s right to free speech and the story’s public interest (the two principles being intertwined, since a free press is deemed to be in the public interest). And since there’s little consensus on what “public interest” actually means, it’s hardly surprising that contention has arisen between newspapers — united in their condemnation of celebrity injunctions, and inclined to stretch the public interest argument to cover many and varied stories — and the judiciary, which has typically applied much narrower parameters to the definition.

The loftiest interpretation of public interest is our common concern with the workings of government, but we’re more often drawn to stories wherein someone’s carefully curated public image conflicts with their private behavior — especially if their image helps them make money. Nothing kills sympathy and stimulates curiosity like the whiff of hypocrisy, elected official or not. In 2010 the footballer and England Captain, Rio Ferdinand, sued the Sunday Mirror for running an interview with a former lover. Claiming a gross invasion of privacy, he sought a worldwide injunction on further publication, as well as damages. During a three-day trial the following year, Mirror Group Newspapers maintained that their story’s public interest hinged on Ferdinand’s appointment to Captain as a reformed character who’d renounced his debauched ways, and on the incongruence of his philandering with a “family man” brand. (Similarly, the application for an injunction by the claimant-who-cannot-yet-be-named was initially refused due to his public portrayal of marital commitment, then granted on appeal.) The judge was persuaded: Ferdinand lost his case and had to pay costs of around £500,000.

It’s estimated that the injunction now in the spotlight will cost double that sum, all for precisely naught now that, pending the outcome of a Supreme Court challenge, the injunction has been lifted. (It is “inappropriate,” ruled the judges, that anyone should be restrained from “saying that which is common knowledge.”) Should this outcome sound the death knell for the celebrity injunction — as many are gleefully proclaiming — it will be fascinating to witness the impact on journalistic conduct. In the post-Leveson, post-phone hacking era, what they used to call Fleet Street is meant to be a more ethical and civilized place, where self-regulation is curbing the worst gutter-press excesses. If the demise of the celebrity injunction augurs a renaissance for ye olde kiss and tell, it would be a small price to pay for a society in which the wealthy and powerful cannot act with impunity, comfortable in the expectation of legally sanctioned censorship.

Photo:Lenscap Photography / Shutterstock.com

A Poem By Cheena Marie Lo

by Mark Bibbins, Editor

towards the amalgamation of larger divisions of the species for purposes of mutual protection

towards some determined point

towards the end of August, and remain for the winter

towards the shore

towards the sea

towards the trees nearest to the field

towards family life

towards the development of higher moral sentiments

towards each other

towards the community

towards his community, that he not only refuses to be rescued

towards our neighbours

towards a new life of mutual support and liberty

towards the peasants; attempts to free them

towards the citizens: a public function, as honorable as any other. An idea

of “justice” to the community, of “right” towards both

producer and consumer

towards the State

towards the end of the winter

towards the end of your sentence

towards the community at large, but also among the co-operators

themselves towards establishing better relations

towards one sort of heroism

towards the establishment of an infinite variety of more or less

permanent institutions for the same purpose.

towards the poorer classes

towards the poor, from whom the well-to-do-people are separated

by their manner of life

towards further progress

toward Medicare and Medicaid expenditures

toward higher income

towards the right questions rather than ready-made formulas

toward achievement of its vision

towards the middle

toward rebuilding

towards the constructivist learning model

toward a curriculum that acknowledges the importance of making students

conscious at a young age of their position in a global society

towards the benefit of a people and a place in need

toward the top of the levee

toward its prisoners

toward the boats

towards the perimeter fence

toward repopulating his jail

toward the center of the city

toward the top of the wall

toward the houses on the other side

toward a geography of incarceration and return

towards a final catastrophe

Born in Manapla, Philippines, Cheena Marie Lo is a genderqueer poet based in Oakland, CA. They coordinate a youth art program at California College of the Arts, and co-edit the literary journal HOLD. A Series of Un/Natural/Disasters is just out from Commune Editions

.

Tenor Colossal

“If I can play again, I’d like to play again. I feel I haven’t quite gotten where I wanted to get to in my music. I’ve had a successful career. I’ve done what I’ve always wanted to do, which is music. I’m 85 years old now, so there is nothing to be angry about. If I can play again, if I can get the medications, these new drugs, then fine, I’ll be able to play again. If not, that’s the way it is. I have accepted it.”

— Hilton Als talks to the [WE NEED A SOMETHING SUPERLATIVE TO “ICONIC” BECAUSE THAT WORD HAS LOST ALL MEANING DUE TO OVERUSE; DITTO “LEGENDARY”] Sonny Rollins for The Pitchfork Review’s jazz issue. There is also an article by Carvell Wallace about Thelonious Monk which I have not yet read, but the man was the greatest composer of the 20th Century, so it would be difficult to fuck that up.

Brian Eno, "Fickle Sun (iii) I'm Set Free"

Brain Eno covering the Velvet Underground is a certain kind of old man heaven, and guess what: I am that kind of old man. Hopefully those of you with less adjacency to death can appreciate it as well. Enjoy.

New York City, April 19, 2016

★★★★ The sky had a pearly discoloration at first and the sun was slow to assert itself. By late morning though, the light was clear and ample. Little cumulus clouds traveled below soft blurry cirrus. On the way out of the dim 1980s concrete bunker of the high school polling place, the spectacle overhead was particularly vivid. Not only bared limbs but quite a few faces were pale in the full force of day. Here and there shirts were glaring white; the notebook page looked blank for a moment. The wind grew lively and chilly. It crumpled and twisted a man’s newspaper as he tried to read on a bench.