Kenneth James Gibson, 'The Evening Falls'

Normally I would use the morning’s music selection to provide you with something energizing in an effort to counteract the stultifying effects of the pervading atmosphere of torpor in which we now go about our lives, but I have come to the conclusion that there is no point. We will never see the sun again. Relieve yourself of any hope you have that things might get better; there is nothing left to you but foreboding and gloom. Also, if you are one of those people who has been bragging on Twitter about how you actually like this weather, go fuck yourself. Sit on a rusty umbrella and open it. Seriously, get the fuck out of here with your “Oh, I love the lack of light! Grim and despondent, that’s what works for me!” crap. Take your pathetic lies to one of those shitty-ass cities in the Pacific Northwest that we only hear about here when one of our fancy magazines decides to write an article about them. “But I think the rain is so beautiful!” I think you shutting the fuck up is so beautiful, okay? This weather is irredeemably awful. None of us likes it. You sicken me. Anyway, here’s a continuous mix of Kenneth James Gibson’s new album The Evening Falls. Evening, you might remember, was what we used to call the period when the sun went down, back when there was actually a sun that came up. Enjoy.

New York City, May 4, 2016

[No stars] Again the drizzly wind was blowing under the still-gray sky. The drizzle kept coming, falling on the people trudging out the door from the fire drill and around the corner and back upstairs. A tour bus went by with an inverted and broken umbrella sticking out the open top. The drizzle thickened into something more than drizzle. Passing tires dragged damp streaks along the roadway. Little puddles gathered at the curbs. Hoods went up. The clouds got darker, with more visible thick parts. Conditions would change only enough that they couldn’t be ignored or taken for granted.

Tweet Engaged

None of you are grasping the deeply awful repercussion of this tweet, which is that people are now going to be making bad food jokes on the basis of stereotypes of race, sex, age, disability, national origin, religion, sexual orientation, and other protected characteristics. Enjoy your timeline!

3D Printing The Void

by Evan Malmgren

Nine months ago, MakerBot’s future seemed tentatively optimistic: the company had just opened a 170,000 square foot factory in Sunset Park, Brooklyn. Brooklyn Borough president Eric Adams spoke at the factory’s grand opening, holding up a 3D-printed nut and bolt as he waxed philosophical on the virtues of “a technology that will move the entire globe.” The press release for the event proclaimed, “‘Made in Brooklyn’ will continue to be inscribed on the back of MakerBot Replicator 3D Printers for years to come.”

Last week, the company announced that it will begin closing that factory, with future production outsourced through Florida-based manufacturer Jabil and most likely offshoring to China. Johan Broer, Director of Public Relations at MakerBot, gave the transition an expected timeframe of roughly six months, saying, “we need to embrace a more flexible manufacturing model that allows us to more quickly scale production up or down.” Current trends suggest down as the more likely of the two directions: MakerBot’s parent company, Stratasys, recently released a financial report that revealed a fifty percent drop in MakerBot’s sales from 2014 to 2015.

This comes on the heels of a difficult year for the company, which severed its relationship with maverick co-founder and former CEO Bre Pettis, cycled through a revolving door of top-level leadership, and suffered two rounds of massive layoffs. Johan Broer cast these changes in an optimistic light, saying that the company had “reshuffled the team […] to position us better for the future.” It’s not difficult to read between the lines: the future looks worryingly uncertain for this once-spunky Brooklyn startup.

As the longtime poster child and one-time presumptive standard-bearer of small-scale “additive manufacturing” — the technical name for the process of 3D printing, which adds rather than strips away material — MakerBot’s rapid rise and equally blistering crash has mapped closely onto the public’s expectations of the technology. The desktop 3D industry is far from dead, but MakerBot’s difficulties are rooted in a broader contraction of the consumer market. The gatekeepers of viral tech-hype have largely stopped trumpeting consumer 3D printers as a revolutionary technology. Now that the dust is beginning to settle on the MakerBot saga, it seems like a good time to ask: what was all the hype about?

For a time, the allure of the desktop 3D printer seemed inescapable. Painting our social feeds with techno-utopian blog posts, a wave of optimistic journalism heralded the devices as a personal tech solution to the crisis of productive alienation. This noise owed no small credit to MakerBot, which rolled out the first consumer-grade 3D printers seven years ago. Pettis spoke in ideological terms of owning the power of manufacturing and being able to make “anything you want;” of “[putting] an interrupt switch on consumerism.” He saw open-source production as a way to make things competitive manufacturing would never incentivize, like DIY solutions to interfacing non-compatible hardware systems. His favorite example was a small converter that could snap Brio tracks onto Duplo blocks. Personal 3D printers would become a freely available catalyst to, in turn, make everything else freely available. It was going to redistribute global production; capitalism was undoing itself!

MakerBot’s Cupcake CNC, the first-ever consumer 3D printer, was released to a messianic overture in 2010. Shortly before its commercial release, Pettis gave a talk about the significance of the technology at IgniteNYC. Bouncing onto the stage with an adorable gawkiness, he introduced his new company: “I’m going to talk about MakerBot, and the future, and the second revolution that’s beginning — that has already begun.” He skipped to his next PowerPoint slide: a photograph of the world’s first commercial desktop 3D printer, under a bold white heading: “INDUSTRIAL REVOLUTION 2.”

The technology was still in its swaddling clothes, but many chose to take it as a proof-of-concept for small-scale, open source production. With the Cupcake’s source files available for download, anyone could make it, and once they had it, they could make anything else. This wasn’t just another nifty gadget for the DIY enthusiast, but a practical tool to democratize the material economy itself. Sure, the Cupcake required religious maintenance and couldn’t produce anything more impressive than monochromatic, granular Yoda effigies, but it was a promise of more to come.

MakerBot delivered on that promise for a few years, releasing successive generations of 3D printers — the Thing-o-Matic in 2011 and the Replicator in early 2012 — that improved upon the technology, simplified its use, and brought the cost of the cheapest at-home 3D printers from over $20,000 to around $1,000. The MakerBot tide rose, carrying a buoyant new startup ecosystem with it. The long-awaited sequel to the critically acclaimed industrial revolution seemed like a plausible sell.

At the end of 2012, though, a new Kickstarter project took the company’s open source faith to trial. The Tangibot was proposed as a cheaper clone of the Replicator, designed from freely available and non-proprietary source files. It was technically legal, but broke an unspoken rule. The Tangibot never went into production, but the threat taught MakerBot a difficult lesson: open-source tech might be good for the public, but it didn’t guarantee a competitive business model. Shortly after the Tangibot failed to secure funding, MakerBot released the Replicator 2, its first closed-source printer. All subsequent models would follow the example.

In the years that followed, MakerBot lost most of its ideological identity along with its profit margin and the goodwill of the maker community. Amidst a slew of patent applications for open-sourced designs and failed closed-source innovations, Pettis sold MakerBot to 3D printing giant Stratasys in 2013, stepped down as CEO in 2014, and left the company altogether in 2015.

The demands of private competition sapped the magic out of MakerBot. Other open-source 3D-printing startups folded — RepRap Professional Ltd. and Solidoodle each ceased operations altogether in early 2016 — and the bulk of the industry shifted to the closed, outsourced model that MakerBot has now fully adopted. Techno-utopian hype gradually abandoned the technology in favor of newer toys like VR and drones, and personal 3D printing went from a revolution to an industry. The maker movement was demoted from a force of social transformation to a geeky subculture; open source had failed to take hold of material production.

The false expectations plaguing the state of 3D printing have been well documented. Broer made this much clear in reference to the troubles facing MakerBot’s Industry City factory: “In 2014, there was a lot of hype around 3D printing and the consumer market, and many people in the industry thought that the consumer market would take off very quickly.” But the saga of the desktop 3D printer is more than just an instance of overbuilt faith in underdeveloped technology. The inevitable failure to meaningfully disrupt global production rests on a radical misperception of the relationship between machinery and production.

The maker movement — including Pettis and the MakerBot of 2009–2012 — has something of a manifesto in The Maker’s Manual: A Practical Guide to the New Industrial Revolution, a book produced by Make magazine. Andrea Maietta and Patrick Di Justo outlined the “magic” of the personal 3D printer:

Today, thanks to the 3D printer, you can create a three-dimensional object just by downloading a ready-to-use file from sites such as Thingiverse or YouMagine and printing it with a specialized device, just like we do with any paper document through a traditional printer.

According to Maietta and Di Justo, 3D printing was going to completely reverse the historical subdivision of mechanized labor. This view was parroted elsewhere in the media, jumping from tech outlets like Motherboard and WIRED, to mainstream publications like The Economist and The Guardian; a feedback loop of industry hype was quickly established. The 3D printer was presented as a universal tool: it could build almost anything, including itself, and it appeared to do so without the need of any human labor. “If only everyone could keep a small-scale 3D printer in their living room,” the logic goes, “then everything would be free!”

It was an appealing idea, but it’s also a fantasy. 3D printing is far from autonomous or labor-free; in fact, in most cases it’s not even very efficient when compared with traditional injection-mold techniques. Global productive forces are already powerful enough to deliver goods in just as large a volume as 3D printers could ever hope to match; the problem is in the distribution, not raw production. Even the most sophisticated 3D printer would need materials to build with, and those materials would need to come from someone, somewhere. Did you really make that Yoda figurine, or was it built by the workers in the factory where the plastic was synthesized, the assembly line where the machinery was arranged, and the warehouses where it all shipped from? 3D printers don’t replace this labor; they simply hide it behind a network of physical space and currency transactions.

In this sense, the 3D printer isn’t part of a “second industrial revolution,” but an extension of the first. The real impact of industrialization wasn’t due to the invention of power machines like steam engines, but the onset of tooled machines, which removed the tools from the hands of workers. 3D printing doesn’t represent an inversion of the subdivision of mechanized labor, then, but an intensification of it. The appearance of mechanical autonomy is an illusion.

Not many technologies have so thoroughly infiltrated the public imagination, on the back of so little demonstrable functionality, as the 3D printer. MakerBot sought to “open source” material production through private enterprise, and Pettis’s vision failed precisely because of that contradiction — it was an attempt to graft a collectivist approach on top of an aggressively private one. “Private production will be completely equitable,” again goes the logic, “if only we can find a way to make everything labor-free.”

Techno-utopian prophets — and the journalists who feed them an audience — speak like science-fiction writers: their promises of tomorrow often project today’s insecurities. In the meantime, sadly, all of our material goods will need to be made somewhere. And in the case of MakerBot Industries, it looks like “somewhere” will be moving from “Brooklyn” to “China.”

GIF: Tony Buser

On The Campaign Trail With John McAfee

by Zachary Schwartz

Photos by Simon Zachary Chetrit

I was waiting in the lobby of The Manhattan at Times Square Hotel when I got a phone call from John McAfee. “Zach, I’ve decided that we’re no longer going to the Libertarian Party debate,” McAfee said in his low, Southern cadence. “It’s far too boring. Instead, we’ll be going to a strip club.” I didn’t know yet how seriously McAfee took his presidential campaign, so I grinned, stuttered a bit, and said “Okay.” There was a pause. “That was a joke,” McAfee said. “I’m sending my bodyguard down to get you.”

This was my second day with the eccentric software developer. The day before, in another hotel, booked under a different name by a third-party — McAfee is famously paranoid — we talked for an hour. He wore sunglasses the entire time and sat with his back to the wall, except for when he’d wheel his rolly chair over and jab a finger in my face to make a point. “The number one problem in the world today,” he said, “is America’s decline in its cybersecurity.” According to McAfee, we’re in a cyber war with the Russians, Chinese, and Iranians, and our technology is twenty years behind.

“I think this is the greatest danger that America has ever faced,” he said gravely. “In a cyber war, the first thing we’re going to lose is our power. A month and a half ago, two fifteen-year-old boys hacked into the Ukrainian power grid. Do you think the Russians and Chinese cannot do the same thing with us? And without power, what happens? We have no power, we have no food.” McAfee’s voice rose in the middle of sentences, brimming with energy. “Half of us would survive a nuclear threat,” he said forcefully. “But no one would survive a cyber attack. No one. And if we do, we’re going to be in tatters on the street eating rats.”

This is McAfee’s strategy: to convince others of an imminent threat that he alone has the solution to. His prophecies of cyber-doom in the early nineties catapulted sales of McAfee Antivirus, the first-ever antivirus software, leading to a $100 million fortune in 1994 when he sold his stake in the company. He used the money to feed his restlessness: opening flight schools, establishing yoga retreats, and founding numerous technocratic ventures. But he found it difficult to cope with the isolation of wealth. In the late aughts, he expatriated, building a compound in Belize, where he planned to research new antibiotics.

Over time, his seemingly innocuous mission unraveled into madness. McAfee lost all sense of personal hygiene, shacked up with a sixteen-year-old he was introduced to by a brothel owner, and attempted to dismantle an organized crime syndicate in a neighboring town. At one point, he claimed, he refused to make a two-million-dollar donation to the Belizean government, and in retaliation, they named him a person of interest in the mysterious murder of his neighbor. McAfee fled from Belize in 2012 and went on the run with Vice, who accidentally revealed his location in a metadata blunder. He evaded both Belizean and Guatemalan authorities before he was apprehended and placed in a Guatemalan jail, until his bodyguard showed up with piles of cash, handing them out “like candy,” he said, and got him out safely.

Now, at seventy, McAfee is running for president on a cybersecurity platform. He formed the “Cyber Party” in September, before realizing the Sisyphean hurdles ahead. “It became clear why Ross Perot, with all of his billions, could only get on thirty-seven states’ ballots,” McAfee said. “While I was running under the Cyber Party, I kept getting calls from the Libertarians. What they said is, ‘We can give you ballot access in all fifty states. And while you keep saying we don’t have a platform regarding cybersecurity, isn’t that what you can bring to us?’ So I think it’s a marriage made in heaven.”

In the 2012 election, the Libertarian nominee, former New Mexico governor Gary Johnson, finished in a distant but significant third place, garnering over a million votes. (Mitt Romney, who finished second, received sixty million.) “I like Gary Johnson,” McAfee told me. “Johnson has done more for the Libertarian Party than anyone. But it should be clear that he’s not presidential material. He’s like a turtle out of his shell, he seems uncomfortable with himself. Imagine him on stage with Donald Trump. It would be horrific. A bloodbath.”

The race for this year’s nomination boils down to three candidates: McAfee, Johnson, and Austin Petersen, who have consistently polled as the top three in their party. Johnson, short on charisma and representing the party’s establishment, is the race’s Hillary Clinton. Petersen, a thirty-five-year-old from Missouri who founded The Libertarian Republic, a popular Libertarian online magazine, is the race’s Marco Rubio, with good looks and rhetorical polish. Johnson and Petersen are the old guard and the rising star, which leaves McAfee as the outsider — the Donald Trump or Bernie Sanders of the race, which, depending on one’s political leanings, makes him either a wackjob or the sole truth-teller on stage.

In the March 1 Minnesota primary, Johnson, Petersen, and McAfee received 75.7, 11.5, and 7.5 percent, respectively. But in the most recent A Libertarian Future online poll, Johnson stood at 38, Petersen at 37, and McAfee at 25 percent. Confusingly, the Libertarian primaries and polling don’t mean or tell us much — at the end of the day, McAfee has to persuade enough independent delegates to cast their votes for him at the convention on the last weekend in May in Orlando, Florida. And as the candidate with the biggest name recognition, he’s very confident: “I will win this convention, you will see,” he told me this morning over the phone.

On April 8, Fox Business News hosted the first-ever nationally televised Libertarian Party debate in New York City. McAfee’s white-haired bodyguard, also named John, escorted me to the hotel room where he was surrounded by an eclectic group: Christopher Thrasher, his broad-shouldered, genial campaign advisor, Rob the video guy, who sported a ponytail and wore a leather jacket with a homemade McAfee patch, and Xanthia, Rob’s red-haired girlfriend. They looked like a small motorcycle gang, reunited for one last hurrah.

“The question is, should we get drunk before the debate?” McAfee said. The mythology of John McAfee almost always involves some combination of guns, drugs, and scantily clad women, so I got ready to toast. But no drinks were poured. McAfee now only drinks occasionally, after thirty-nine years without alcohol, and he claims to have not done hallucinogenic drugs in twenty-five years — “oh God no, the flashbacks are bad enough,” he said.

The group left the hotel and headed toward Fox Business News headquarters, only a few blocks away. After McAfee took pictures with a fawning receptionist, we were ushered into the prep room, where Gary Johnson and Austin Petersen were already present. McAfee was the only candidate to have brought an entourage. “So, can we shoot heroin in here?” McAfee deadpanned as he sat down. Petersen mentioned a party after the debate. McAfee invited Johnson from across the room. “I’m on a little on the sick end,” Johnson said dryly, “and I haven’t had a drink for twenty-nine years.” “Well, I have some opium,” McAfee said. Johnson ignored him.

John Stossel, the moderator, came in to greet the candidates before the debate began. I asked McAfee if he was nervous, and he seemed surprised by the question. “This is nothing compared to fleeing the Guatemalan military. Or the Belizean, for that matter,” he said, and flashed a smile before heading into the bright lights of the studio, to the applause of the alt-right.

“Welcome to our Libertarian Party Forum,” Stossel said to the rolling camera. “Given that the presidential frontrunners, Hillary Clinton and Donald Trump have huge unfavorability ratings, it’s time to hear from alternatives. So, with us tonight are the three leading Libertarian candidates!” McAfee gave his opening statement between Johnson’s and Petersen’s. “Libertarianism is grounded in the concept of liberty,” he began. His voice rose with an imploring lilt, and had a measured rhythm. McAfee continued: “But what is liberty? Liberty means that our minds and our bodies belong to ourselves. Liberty is lost when governments decide what is right or wrong regarding what we may do with ourselves.” The audience murmured in agreement.

During the debate, McAfee made the same jokes on national television that he did in private conversation. “I met him at a gay bar,” he said of Petersen. When Stossel said, “People say Libertarians love drugs,” McAfee responded: “Well, what is a drug?” Almost everyone in America drinks alcohol and smokes cigarettes. Aren’t those drugs?” When Stossel brought up ISIS, McAfee questioned the necessity of war. “Well, there’s people that want to kill us,” Stossel said. “I don’t buy that,” McAfee said. During a break, after a producer instructed the audience to clap on certain cues, McAfee quipped, “I think we, as Libertarians, should ignore her instructions.” Everyone laughed.

We returned to the prep room to watch Fox’s commentators analyze the debate on TV. “I thought Gary Johnson made the best practical case to a curious mainstream audience,” one of the pundits said. She compared McAfee to a stoned college roommate. “What are drugs? What is war?” She giggled. McAfee, reclining on a couch, had no reaction.

We left a few moments later, right behind the audience. McAfee lit a cigarette as soon as we got outside. “We got fucked!” He exclaimed. He started pacing around. “Did you see how those two commentators were friends with Gary Johnson? Did you see how she came in and gave him a big hug at the beginning?”

This was my first glimpse of Crisis McAfee, the form closest to his public caricature — pacing, chain-smoking, firing off expletives as he might have done when the Guatemalan military was closing in on his location. But before long, he was joking and smiling again, putting his arm around any fan who asked to take a picture. After the crowd fell away, McAfee approached our group and asked my photographer to take us to a “speakeasy bar” where the “conversation is visceral, not cerebral.”

We left with several Fox Business News people in tow, including John Stossel, and ended up at Blue Bar in the Algonquin Hotel. McAfee described his popularity to a skeptical Stossel. “I go to Russia, Ukraine, France, and I get mobbed at airports,” he said. “In Russia they handed me a magazine that I had never seen before with me on the cover.”

I stepped outside with McAfee’s senior advisor, Christopher Thrasher. The entire nominating process rests on the approaching convention, when the party delegates will vote. Thrasher spoke in a hush, even though we were outside.“The secret is that Petersen and Johnson are already topped out in their support,” he said. “If we can keep Johnson from winning on the first ballot, meaning he gets less than fifty-percent of the vote, then I am confident we can win the nomination on subsequent ballots.” No matter the nominee, the Libertarian Party candidate is unlikely to win the general election. But if he receives five percent of the popular vote, the government is obligated to start providing general-election funding to the party.

Five years ago, McAfee was on the run from Central American militias. Now, at seventy and married, he’s committed to preaching the two things that have shaped his life: cybersecurity and liberty. McAfee campaigns on a dire message: “We are on the brink of devastation,” he warned me many times during our two days together. “It doesn’t even have to be me, but our country is lost if we do not have a cybersecurity expert as president.”

McAfee has proved adept at attracting the media’s attention with stunts like offering to hack the San Bernadino shooter’s iPhone and publicly criticizing the FBI on their cybersecurity. But by seeking public office, he’s made another thing clear — John McAfee doesn’t need to hide anymore. After the drugs, after the wealth, after the jungle, the yoga scholar seems to have found his balance in the only other place crazy enough for him: the campaign trail.

Sturgill Simpson, "Breakers Roar"

This is probably the prettiest track from Sturgill Simpson’s A Sailor’s Guide to Earth, which I will keep insisting that you to listen to until you finally realize I have your best interests at heart here. Enjoy.

Academia 101: Intro To Lab Reports

by Josephine Livingstone

I handed in my dissertation a year ago today. A month later, I stood up at the end of my defense and shook a professor’s hand as she smiled and said, “Congratulations, Doctor Livingstone.”

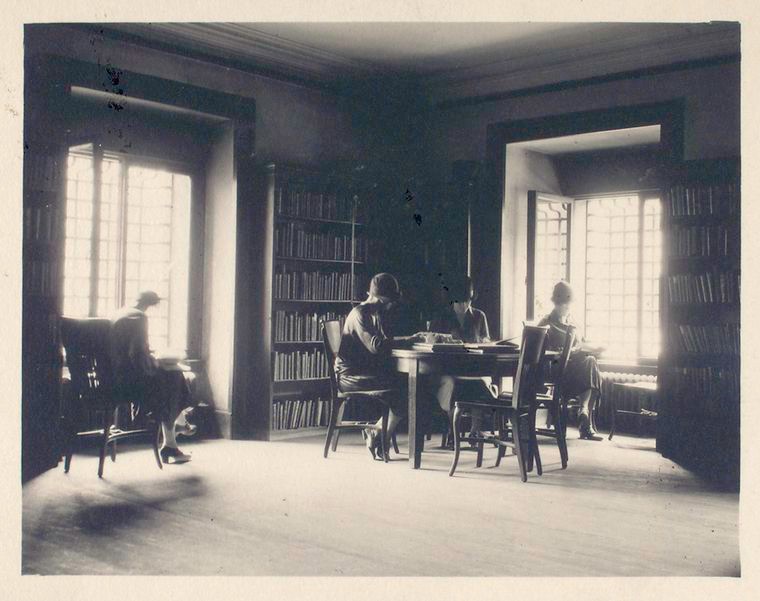

That feels like a very long time ago. This semester, I got my dream teaching position, but when the last class ended a few days ago, the job did too. I was filling in for a professor on leave, so I got to borrow her office and put my books on her shelf. I got to look out her window and talk to my students over a massive wooden desk; it was like living inside a waking dream.

For people graduating with a PhD in the humanities these days, the chances of obtaining meaningful academic employment are really, really bad. The river of university cash flows no more. The opportunities have thinned so drastically that hundreds of equally well-qualified competitors go up for every single position, no matter how rubbish the college or undesirable the location. One recent rejection letter told me that seven hundred people had applied for the two postdoc spots. The letter-writer sounded confused and regretful.

A fog of complacency has enveloped early-stage grad students and tenured professors alike. In the first couple years of a doctorate, the job search is so far off that it doesn’t feel real. The tenured professors are employed for life and busy with their own work, so they don’t have much motivation to warn their students of what’s coming. Both groups pretend nothing is happening, because nothing is, and a whole load of newly minted doctors lose their minds every year. Am I willing to go round after round on the job market like the guy from the movie who slugs the parking meters? No. Do I think this situation is ridiculous? Yes! But do I regret doing a PhD? Not with a single fiber of my being.

For one thing, I turned a bound copy of my dissertation upside down and now use it as a mousepad at one of my jobs. The plastic on the back has exactly the right texture. For another, the five years I spent on my PhD were the most glowingly meaningful of my life. Graduate school paid me to read and think and ponder, then gave me the skills and self-belief to construct arguments out of those thoughts. I never once got out of bed early, and yet I can read all these medieval languages! It is unclear whether I’ll ever get a proper teaching job ever again. But I won’t give up research and writing just because there’s no place for me at a university. The only thing to do must be to throw more work at the problem.

Here at The Awl, I’m going to be sending you dispatches from the strangest corners of academia. I’ll cover the grad student and the emeritus professor, the tenure-tracked and the unemployed. We’ll meet biologists, angry critics, wistful scholars, musicologists, joyful discoverers. Next week, for example, a Canadian biologist in the field of social evolution will tell us about hymenoptera and “sib-mating” (that’s biology-speak for incest). I can’t wait!

Researchers are just people, even when they win the Nobel prize. But until they earn ridiculous laurels or get a big-name job — which will never happen to most of us — academics toil in obscurity. But they’re heroic still, even when they can’t make a living. Lab Reports is going to be a series of postcards from the intellectual edge, and I can’t wait to go back to school.

Photo: NYPL / Digital Collections

A Poem By Lee Upton

by Mark Bibbins, Editor

An Epic for Mother’s Day

Epic: “a poem including history” — Ezra Pound

A poem with history

a history with poems in it

in history with a poem

a history of the needle and wrench and cable

and a pretty dress and a grave

and a pretty dress in a grave

roll the stone from the grave

raise the corpse and breathe into her mouth

take Ovid from the shelf and change shapes in history

in history with a poem on a cushion or in a field

or on a swing or force fed

in a house or a trench

a body that pushes history out.

Lee Upton’s most recent book is Bottle the Bottles the Bottles the Bottles

(Cleveland State University Poetry Center, 2015). Her poems have appeared in The New Yorker, The New Republic, Poetry, American Poetry Review, and elsewhere.

Closer To Fine

“It’s easier to sell the first two than the entire panel where the dog melts into nothingness.”

— Here’s an interview with the guy behind “On Fire,” the popular comic that you may have seen in many of the meme-friendly environments that our modern age offers up in place of churches as spaces of congregation for the lonely and uncertain. What I particularly appreciate about this quote is how it demonstrates the limits of what we will accept when it comes to laughing about how terrible life truly is: We’ll buy the dog telling himself that everything is okay while the flames burn all around him, but the inevitable results of that act of self-delusion are a little too real to slap on a T-shirt and show to the world.