The Supreme Court Justice Who Shot A Senator

by Zach Dorfman

If, like me, you are dispirited by our national political climate, you may occasionally entertain the sense that you are witness to an era of unprecedented moral debasement. Creeping oligarchy, the re-emergence of an atavistic paleo-conservatism, the slow death-wheeze of the fourth estate, the rise of a relentlessly cheery techno-utopian Gatsby class — we’ve got a lot working against us. But if you think our era is defined by its high concentration of professional reprobates, or that the stakes for our republic are particularly high, you might find lukewarm comfort in the story of Judge David Smith Terry.

In the pantheon of salty, contemptuous bastards in American politics, not many can out-do Terry, a bowie-wielding, ardent-pro-slavery Texan with a volcanic temper, who rose to become Chief Justice of the California Supreme Court in the mid-nineteenth century. Like some shadow-character from Blood Meridian, Terry’s life mixed tragedy, vulgarity, absurdity, and spite in equal measure.

Terry was a nationally infamous figure in his own day — no mean feat, in a time when travel back East often meant a seaward departure via the Golden Gate, and an overland trip through the jungles of Panama. There was a wealth of contemporary writing about the judge during the nineteenth century, most of it highly tendentious, portraying Terry as either a rough-and-tumble all-American hero or Lucifer instantiated. (“Blood, blood, blood, seems to be the only substance in nature capable of slaking the thirst of this man-beast,” wrote the San Francisco Bulletin.) But there was a steep drop-off in interest in Terry after his death. In fact, the most recent book about him, a blithely sympathetic biography, David S. Terry of California: Dueling Judge, by Albert Russell Buchanan, a history professor at UC Santa Barbara, is itself sixty years old.

Born in Kentucky, and raised in Mississippi and Texas after his father abandoned the family, Terry fought in the Texas Revolution and, later, in the Mexican-American War. He studied law and headed, like so many other self-aggrandizers then and now, to California to make his fortune during the Gold Rush of 1849. It was there that he developed his reputation as a bit of a stabby hothead, inclined to settle legal or personal disputes with his giant knife, which he always kept sheathed at his side. (Once, in a fit of pique over an unflattering piece about him published anonymously in the Pacific Statesman, he reportedly broke a cane over an editor’s head, then waved his knife him, shouting, “Now, damn you, give me that name or I’ll take your life!”)

Terry’s reputation did not stymie his political ambitions. After a few failed attempts at running for office, Terry was elected in 1855 to the California Supreme Court as a member of the Know-Nothing Party at the age of thirty-three. Most other men would have settled into the kind of staid, stable life promised by a prominent civic position. But Terry’s penchant for violence was rivaled only by his comic capacity for high dudgeon.

In 1856, the year after he was elected to the state Supreme Court, Terry stabbed a man in the neck during a street brawl in downtown San Francisco. The man was a member of the San Francisco Vigilance Committee of 1856, which had recently overthrown the local government in response to its lawlessness and corruption. Terry was arrested, imprisoned, and tried. When Terry’s victim failed to succumb to his injuries, the judge’s release became more politically palatable for Vigilante leaders, who were under pressure to hang Terry for his crime, but did not wish to incur the wrath of the Federal Government. Terry’s speedy trial concluded under highly irregular circumstances, and he was acquitted.

In 1859, at the Democratic convention in Sacramento, Terry launched a blistering attack against U.S. Senator David Broderick, whom he blamed for blocking his nomination to a second term on the state Supreme Court. Broderick, a former tavern owner, was raised in New York City and schooled in Tammany Hall machine politics; he was also a leader of the abolitionist wing of the party. During his convention speech, Terry accused his enemies in the party of being “the personal chattels of a single individual,” belonging “heart and soul, body and breeches, to David C. Broderick.” Understandably displeased, Senator Broderick chastised the Chief Justice as a “damned miserable wretch” to a friend of Terry’s during breakfast a few days later at a San Francisco hotel.

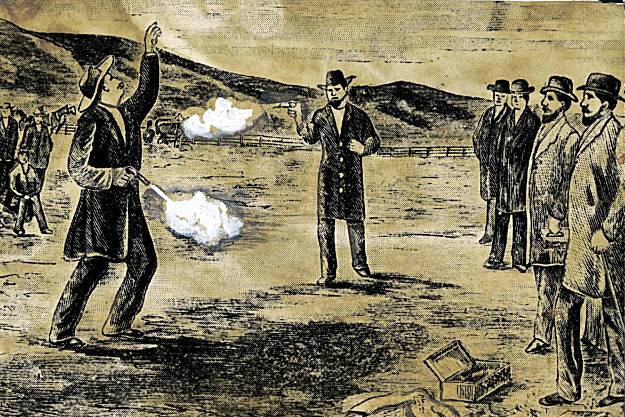

Terry could not countenance this affront to his honor, and subsequently challenged Broderick to a duel. On the cold, misty morning of September 13, 1859, the two men squared off in a verdant ravine just over the San Francisco city line, near the south side of Lake Merced. Broderick fired first, and missed. Terry did not. The senator hung on for a few feverish days, and then died (but not before he claimed, on his deathbed, that he was murdered for opposing “slavery and a corrupt administration”). Fairly or not, the duel was widely seen thereafter as a proxy battle for the pro- and anti-slavery constituencies in California, and across the entire country.

Terry temporarily abandoned politics. He made his way to Nevada, attempting to stake a claim in gold country. When it became clear that the South would secede from the Union, Terry was swept up by the passions of the day. In 1863, he snuck out of California — Unionist officials there kept a close eye on him, since his sympathies were well known — to return to his native Texas to fight for the Confederacy during the war. He was wounded at the Battle of Chickamauga, and subsequently escaped to Mexico with a group of Confederate dead-enders when the cause was very clearly lost. After an aimless three-year period in Mexico, Terry returned to California, and resumed his relatively prominent place in local life in Stockton. He seemed to mellow with age.

Terry’s first wife, Cornelia Runnels, had always been a moderating influence on the judge, but he did not choose wisely in love again. After Cornelia died in 1884, he married a boisterous, vivacious woman twenty-seven years his junior

named Sarah Althea, who was a client of his. Althea was already locally infamous when Terry agreed to represent her: she claimed (falsely, it appears) to be the secret ex-wife of U.S. Senator William Sharon of Nevada and demanded her share of the senator’s considerable wealth. Terry felt the presiding judge, Stephen J. Field — who was also a sitting federal justice of the Supreme Court (and a Unionist Lincoln appointee) — was prejudiced against his client (his wife). The judge ruled against them. In the melee after the decision, Terry assaulted a number of court officials, and was sent to jail for six months.

Terry did not forgive this perceived injustice, and his begrudging attitude led to his rapid demise. On August 14, 1889, roughly six months after his release from jail, Terry happened to travel with his wife from Sacramento to San Francisco on the very same train as Judge Field. Terry spied the Supreme Court Justice during a stop at a stationhouse dining room in the San Joaquin Valley, and purportedly rushed at the judge and slapped him upside the head. Terry was promptly shot to death by a U.S. Marshall; he was sixty-six. Sarah Althea returned for a brief time to San Francisco, but soon came completely untethered, and was sent to a sanitarium in Stockton, where she spent the next forty years of her life.

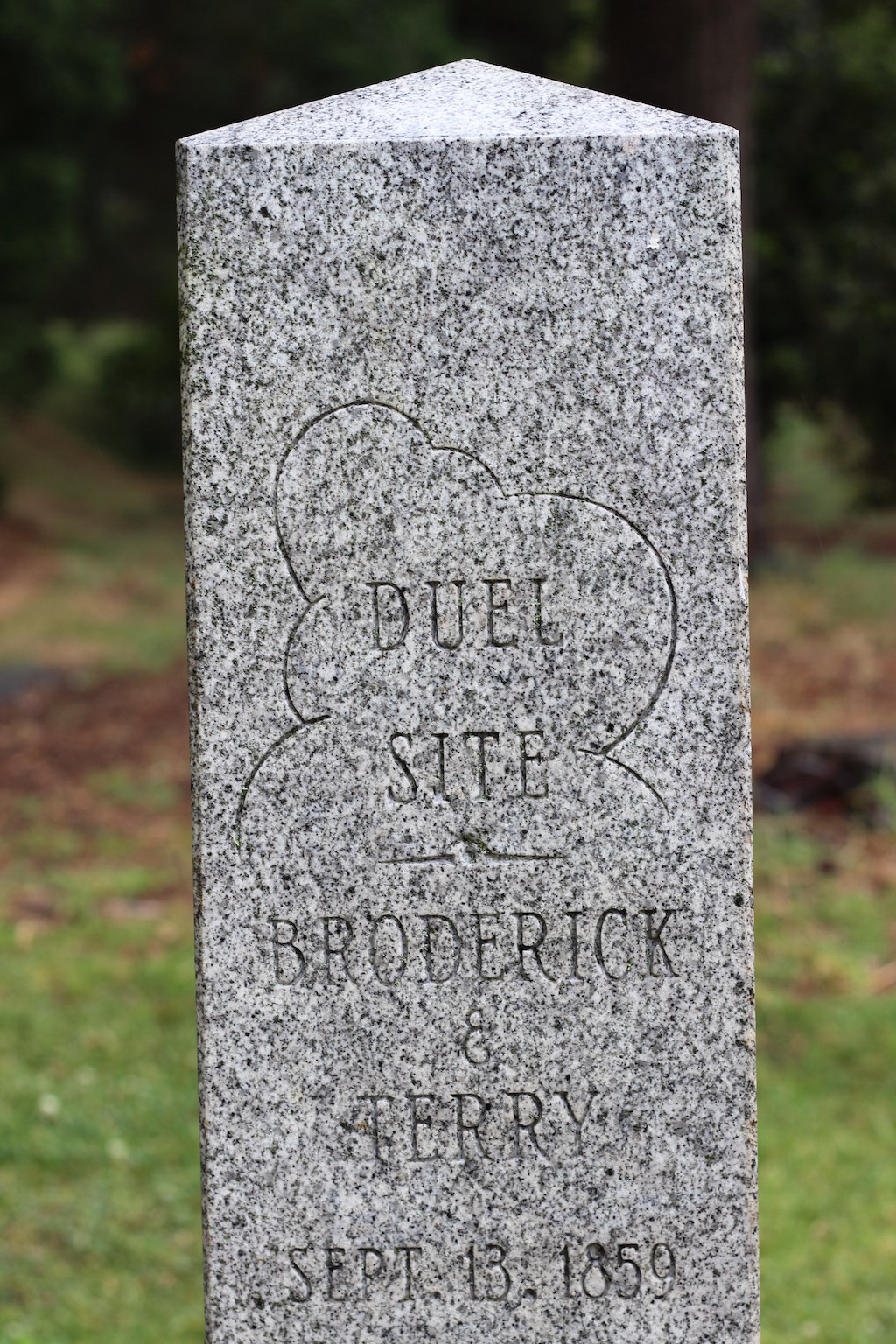

With a little effort, you can still visit the Terry-Broderick duel site today. If you head toward the ocean on John Daly Boulevard — passing the Chipotle and Home Depot and T.J. Maxx — you will eventually reach the neat, manicured upper-middle-class Westlake neighborhood, the very one made famous for its “ticky-tacky” houses. Hidden between two of the homes is a little wood-chipped path that leads to the site.

You can only access the park from the south. To the north, a ravine raises steeply to the lake. To the west is an exclusive country club, to the east is an even more exclusive one; the golf courses of both are visible through the eucalyptus. There are blooming wild calla lilies, and cigarette butts, and fresh coyote scat. In the center of the clearing there is a small obelisk commemorating the site. A little farther down the path are two older stone pillars marking the exact spots where Broderick and Terry stood when they shot at one other, maybe twenty steps apart.

The Terry-Broderick duel si

te was among the first recognized by the state as worthy of official commemoration, and designated as such in 1932. California — and the Bay Area in particular — tries to perpetuate a myth of continual reinvention, but the site provides a small bit of tangible proof that America’s venomous nineteenth-century politics transported themselves all the way out to the Pacific.

Thankfully, organized violence is no longer considered an acceptable way to settle domestic political disputes. We will probably never see a character like Terry, with his George Wallace-meets-Crocodile Dundee vibe, again. But the robust berserker streak in American life? That, as the last six months have made abundantly clear, is here to stay.

Buried In The David Chang Backlash

Is the bloom off the David Chang rose? I don’t know and I don’t care; as sad and superficial as my life is I am still not shallow enough that signs of an incipient backlash to the Momofuku empire are anything I might be concerned about. However, I am shallow enough to note that, at least according to a cursory search, this is the first reference to the late GG Allin in a New York Times restaurant review. You never believe it when you’re young, but it’s true: If you live long enough you will see just about everything.

Guy Clark, 1941-2016

The Austin American-Statesman refers to Guy Clark, whose death was announced this morning, as “Legendary Texas songwriter,” and I cannot think of a more accurate description. This reissue of his first two records is a good place to start if you are unfamiliar with his work. Clark was 74.

Róisín Murphy, "Ten Miles High"

I can’t decide if Róisín Murphy’s forthcoming Take Her Up To Monto is brilliant or disturbing, which probably means it’s a little of both. This video is the perfect encapsulation of that. Enjoy.

New York City, May 15, 2016

★★★ White cumulus, all plump curves, shone above the West Side. The four-year-old’s hoodie had been mislaid in the changing weather and all that could be found was a hand-me-down windbreaker. Outside was just mild enough for him to refuse to wear it. When the LIRR surfaced in Queens, the clouds had come together in almost unbroken gray and white, the gaps between them so narrow they could only be seen near overhead. Light fell here and there on the shadowed city. Young women in last night’s bare-legged outfits groaned about the evening just concluded. Sudden red — a blaze of azalea? — went by in someone’s front yard. At the end of lunch, a few umbrellas were out on the streets of Flushing. Jets came in low, round and heavy, booming under the now-solid ceiling. Up on the train platform it was so cold the four-year-old gave up and accepted the windbreaker. A man and two children scurried along the eastbound side, cringing in shorts and sweatshirts. Sun fell briefly onto the return train. More sun came down on the West 60s, but for the moment only there. By late afternoon the clouds had broken again, though, and the wind was shaking the bright leaves of the shrubbery in the rooftop planters across the avenue. A strange formless cloud hovered in the west, a dark but somehow luminous blur. The blur then revealed itself to be rain, glittering and blowing in the open window through the clear returning light. It passed and the west was fully clear, with the tiny silent speck of an airplane crossing it.

Are You Afraid Of The Dark Patterns?

by Owen Phillips

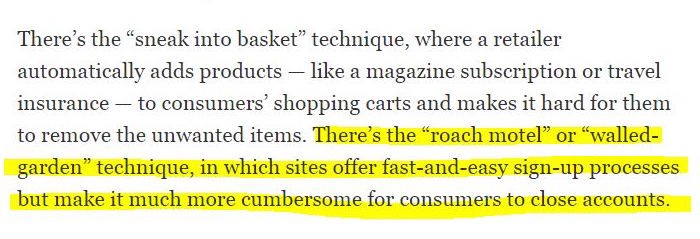

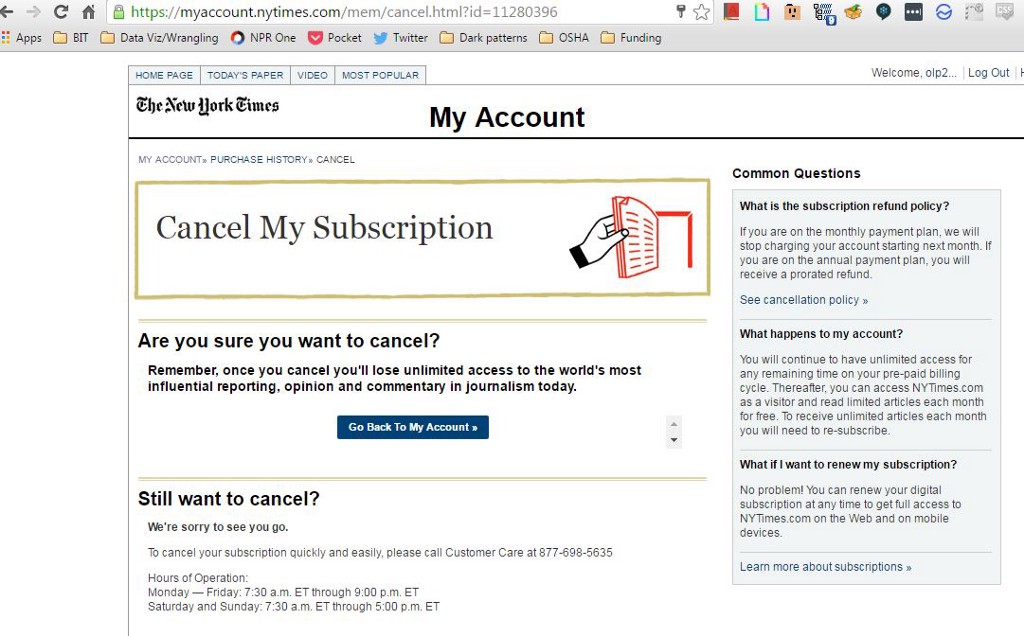

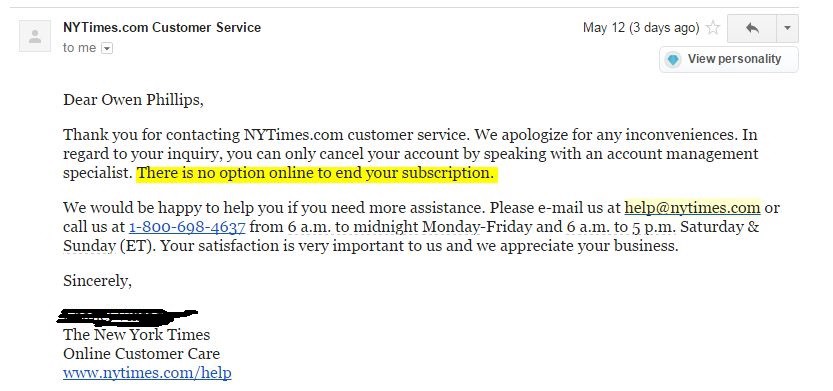

Over the weekend, the New York Times raised concerns over “dark patterns”: web interfaces carefully crafted to manipulate users. For example, there’s the “roach motel,” named after the brand of insect trap that provides a seamless sign-up, but a difficult cancellation process. More common, though, are the websites that either hide the option to unsubscribe from their newsletters or just obfuscate the option to opt-out.

Harry Brignull, a user-experience consultant, coined the term in 2010 and began logging various types on darkpatterns.org. Ryainair, Audible, and Skype have all been featured. Brignull said his goal was to draw attention to the issue and shame the websites who use them.

Let the Walk of Atonement begin:

At Sephora, unsubscribing is as simple as removing a check. But as soon as a user agrees to the terms and conditions the box rechecks itself. Choice is an illusion.

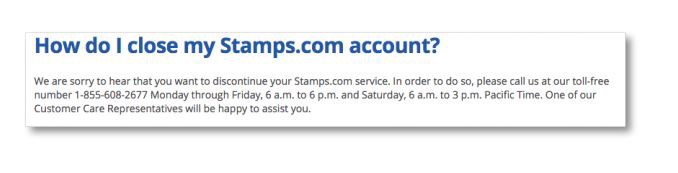

Stamps.com is a classic roach motel — you can sign up online, but you can’t cancel online.

(Or you could do what one what one commenter on Hacker News suggests…)

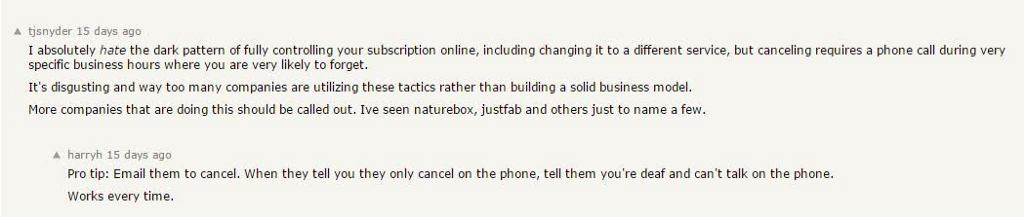

Allegedly, there is an option to unsubscribe somewhere in this email from JetBlue.

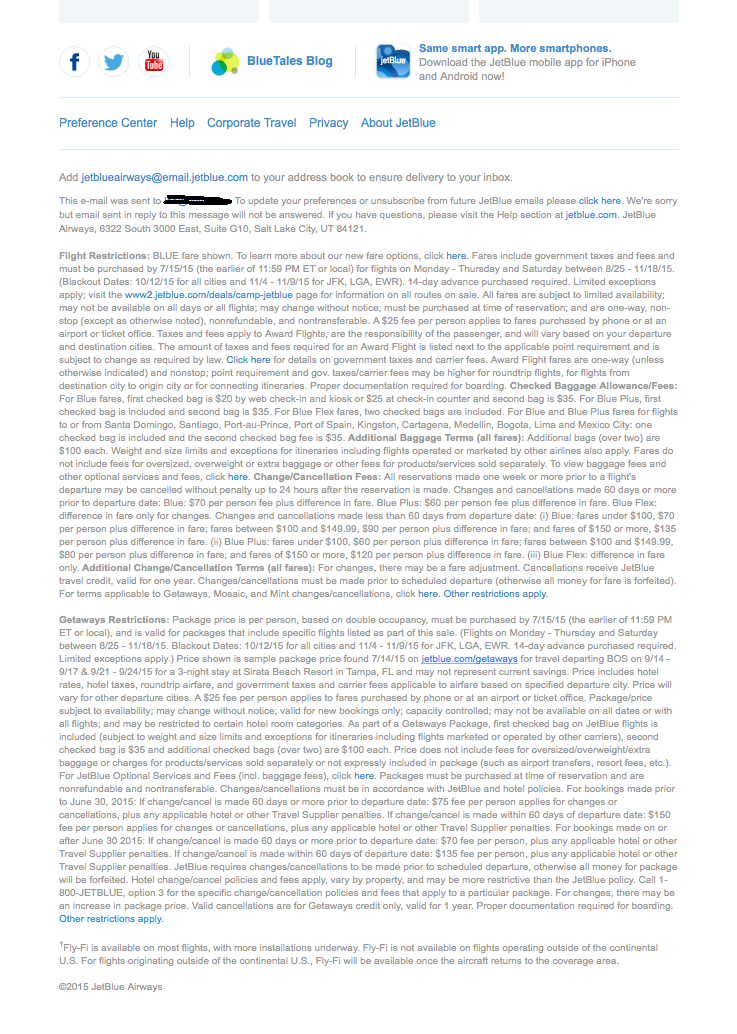

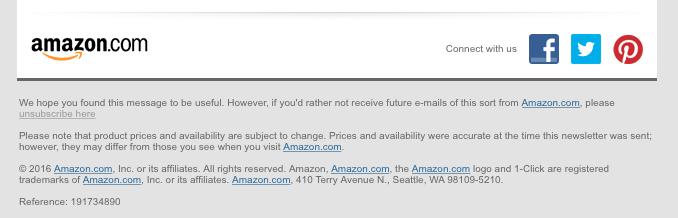

Amazon changes the color of the font of the unsubscribe option.

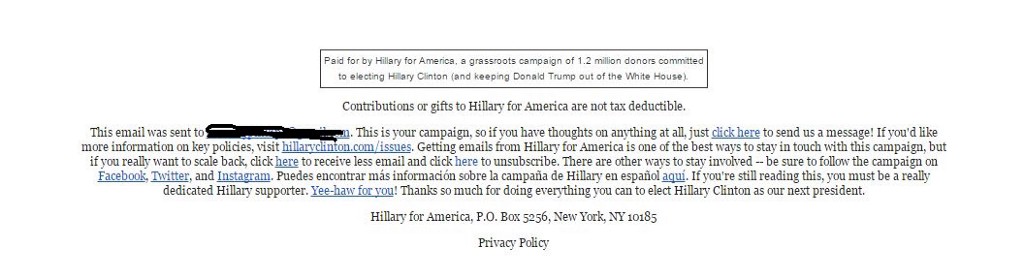

I spy with my little eye an “unsubscribe” from Hillary for America.

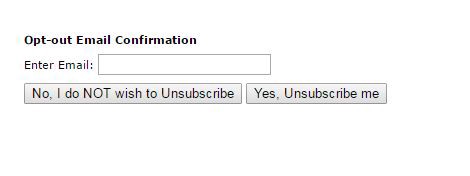

Double negatives aren’t not used on hillaryclinton.com.

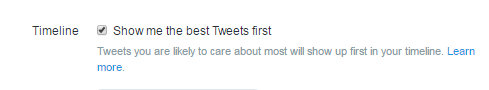

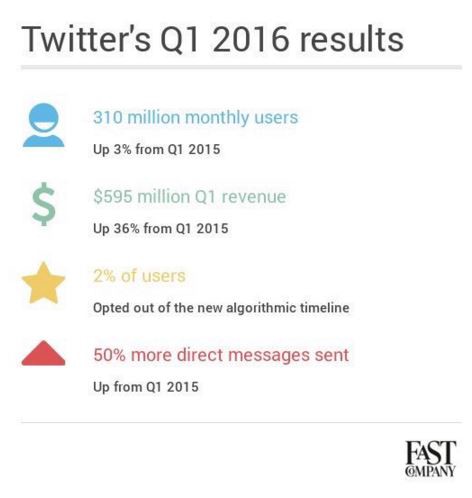

100 percent of Twitter users bitched about the new algorithmic timeline. Only 2 percent opted out.

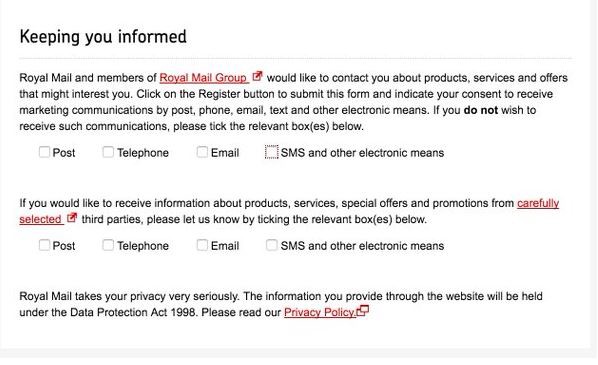

The Royal Mail, the UK’s largest postal service, first tells users to check a box if they do not wish to receive communications, followed by instructions to check a box if they would like to receive emails from third parties.

The path of least resistance leads to an inbox full of emails from Ticketmaster.

Shady dark pattern by @ticketmaster asks users to check boxes to unsubscribe from their email notifications pic.twitter.com/17qHVu4PXZ

— mark o (@mopland) October 30, 2015

“At least they give us the option.” How progressive of Shutterstock!

@Shutterstock “Auto-Renew” defaults to “On” — another #darkpattern (but at least they give us the option) pic.twitter.com/82fVdrZsJl — Kyle Becker (@Kyle__Becker) October 25, 2015

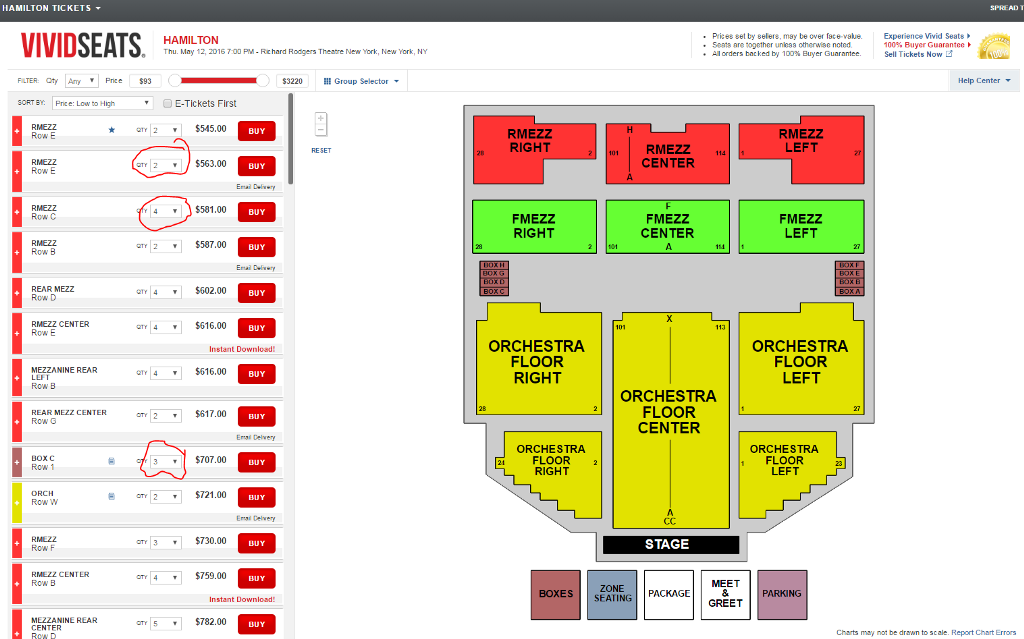

When you go to buy a ticket to that musical show everyone is on about, Vivid Seats gives you a whole bunch of options for groups of two, three, and four. But the prices they show are for ONE Hamilton ticket — you don’t learn that until you’re on the payment page.

— Let’s end this tour with one of those roach motels the New York Times is talking about:

Whose 0s and 1s Are You Plundering?

“Many of us are sensitive to the case put forward by countries that have seen their treasures dispersed around the globe; but while playing Uncharted or Tomb Raider, we’ll spend hours of our free time engaged in the process of removing valuable cultural artefacts from their native homes. We’ll happily lose ourselves in the wonderful escapism — the exotic locations, the intriguing mythologies — with little thought as to what it means to inhabit these characters, and to be made complicit in their actions.”

— It really makes you think.

Sleeping With The Bees

by Josephine Livingstone

Is it a coincidence that insect is an anagram of incest? Yes, but it’s a good one. As Nick Davies explained to me, high levels of breeding between siblings is not unusual in insect societies, especially haplodiploid ones (we’ll get to that). “It’s not just an anagram,” he told me, “It’s also a near-homophone.” This has led to a lot of confusion at parties, because Davies is a researcher in social evolution. Insect incest is kind of his thing.

In Davies’s field, they don’t call sex between siblings incest, they call it “sib-mating.” They use a different word because humans and insects are fundamentally different. An ant mating with its sibling means something for ant society in structural terms; a person sleeping with their sister means something totally different, because humans code behavior in cultural terms. Culture, Davies thinks, is more like a network of shareable information and thought. Societies are just “any semi-permanent aggregations of individuals through which at least some cooperation is enabled.”

I’m drawn to Davies’s research for the generosity of its approach: the most encompassing history of life on earth and minutely subtle community dynamics of wasps are part of the same object of study. Davies is a DPhil* candidate in the Mathematical Institute at the University of Oxford, although his day-to-day research takes place in the Department of Zoology. He’s handing in his thesis soon. It’s called ‘Cooperation and Conflict Across the Major Transitions,’ which he admits is very general: “It’s largely a bullshit title that I made up when I didn’t know what I was doing.”

His field conceives of evolution in terms of “major transitions,” summarizing the history of life as a series of shifts between levels: from genes into genomes, cells into eukaryotic cells, and multicellular organisms into societies, which can act as individuals in their own right. Davies’ research focuses on the social Hymenoptera (the order of insects including bees, wasps, and ants), because they form some of the most advanced examples of cohesive societies in the animal kingdom. They’ve also lent us some remarkably powerful metaphors: we talk about the hivemind, swarms, and drones. The queen bee is bossy, and a hard worker is a busy bee. But that language is fairly figurative and long dissociated from its original meaning — social insects have sterile workers who don’t reproduce, drones and queens, who do.

A better working analogy for an insect community is in our bodies. Most of our cells are somatic, or body cells, which don’t really reproduce. But some are germline cells, like sperm or eggs, which get to pass on their specific copy of the genome. While an insect colony comprises many individuals, it can also be thought of as a body made up of bees (!) that sends out its reproductive cells into the world. “That reminds me of Machiavelli’s theory of the state,” I said. Davies pointed out that I meant Hobbes’s body politic.

A lot of different species, from bacteria to animals to plants, have highly social lives: they interact, compete, and cooperate with other individuals. With Laura Ross and Andy Gardner, Davies has co-written a paper forthcoming in Ecology Letters, called ‘The Ecology of Sex Explains Patterns of Helping in Arthropod Societies,’ about the evolution of altruistic behavior in arthropod societies. Davies got a little frustrated while explaining it to me, since it had been difficult enough for him and his collaborators to distill their findings into a 5,000-word article.

In the Hymenoptera, only females contribute to colony tasks. Whenever you see an ant scouting or foraging for food, “It’s a girl ant,” Davies said. The males are produced late in the colony lifecycle: they go out and mate, then die right away. In termite societies (which fall in the cockroach order, Blattodea), both sexes help out, and there can even be sex-specific task specialization — females might be soldiers, males might be workers. Traditionally, Davies said, this phenomenon has been explained by the theory of “kin selection” (organisms are driven to ensure the success of their relatives as a means of preserving their own genes) first outlined by the evolutionary biologist W.D. Hamilton. But why do both sexes help in termites, whereas in the Hymenoptera only females help?

Like humans, termites are diploid — they have one set of chromosomes from their mother, and one from their father. In the Hymenoptera, however, males are haplodiploid, meaning they only have one set of chromosomes, inherited from their mothers, while females have the usual two. Because of this, we see what Davies called “some weird relatedness asymmetries,” between the sexes. If you’re a termite, you’re related to your siblings by one half, no matter your sex. In a Hymenoptera colony, however, females are more related to their sisters than their offspring.

Hamilton hypothesized that organisms helped out their relatives depending on how related they were to each other. Your children share part of your genes, but so do your uncle and cousin and grandma, so acting altruistically to ensure their survival is almost as good as investing in your own offspring. Overall, then, Hamilton thought that high relatedness between sisters might explain why females help in the Hymenoptera. But that doesn’t really work: not only are haplodiploid females more related to their sisters than they are to their own offspring, they’re also less related to their brothers, and these two effects cancel out. It was an elegant hypothesis, but not a true one.

Davies, Ross, and Gardner’s new paper asks: if Hamilton’s haplodiploidy hypothesis doesn’t explain the sex of helpers in animal societies, what are some factors that might? Pre-adaption, when a trait used by an organism for one purpose is co-opted for another, is one. For example, the social descendants of solitary wasps have repurposed their syringe-like ovipositors — originally used to lay eggs inside figs, or other insects’ bodies, or other insects’ larvae — as a sting, for colony defense. This may be one reason why females, not males, defend the colonies of bees, wasps, and ants.

Sib-mating is another potential factor. As a general trend among animals, females spend their energy on making offspring, while males spend their energy on competing with other males for mating opportunities. But when a species has high levels of sib-mating, the males might be especially willing to invest in help instead of reproduction, since they’d otherwise be competing with copies of their own genes. Sib-mating could therefore promote helping by males rather than females.

Anyway, I shouldn’t give away the ending of the paper. Look it up in Ecology Letters soon if you want to know more. When Davies was talking about insects helping out their mothers, I couldn’t help but think it was adorable. But I instantly felt guilty for anthropomorphizing the bugs. “It’s inevitable,” he said. “It happens to everybody.” When Davies was first starting out, he wasn’t that interested in insects. Now, he thinks bees and ants are cute. He works in a lab with a bunch of microbiologists, and he’s heard them coo over E. coli.

It struck me that people must often want to talk to Davies about evolutionary psychology. “Yeah, they do,” he said. “It’s too bad.” He worries that some people might assume that he’s racist, or sexist, or a weirdo; one of those people who chalks up human difference to the experiences of the ‘cavemen.’ (The caveman idea, in principle, is not the problem, Davies said, but culture makes everything more complicated.) “If I don’t really want to talk to someone about evolution,” Davies said, “I will say my work has no relevance for humans, and that I never think about humans at all.” I don’t think that’s true, but it seems like a good strategy.

Davies told me that he got into science because he wanted to know what makes the world work; it didn’t occur to him as a young kid that philosophy or art might hold those answers. “I could imagine myself as a scientist,” he said, “but couldn’t imagine that I would ever even meet, say, a writer.” It was funny to hear him say that, because Davies also acts and does comedy. Although he didn’t like biology much at school, the older he got, the more he understood that the science of life led held answers to the biggest questions. He grew “less interested in what planets were made of and more interested in what being alive is made of.” Davies gradually realized that evolution could hold a partial answer to that question, and that wisdom and comfort might nestle among ants as much as it lies between the pages of big novels. “That was all I needed,” he said.

*DPhil means the same thing as PhD: they’re abbreviations of the same Latin phrase with the words in a different order. I think.

Photo: Alan Taylor

Traducción Es Muy Dificil

“It is a frustrating practice, because one sentence will come out beautifully, and the next one will just be so difficult, and you might end up with something you’re not really happy with, but you can’t come up with anything better. A lot of people agree that translation is really about compromise; you can’t get the sense exactly unless you sacrifice the sound, and vice versa. The constraints you work with are challenging and exciting, but the other side of that is you may not come out with very good answers.”

— You might enjoy this interview on translation with the amazing Lydia Davis. If you are interested in another view on the difficulties of translation Tim Parks recently did a terrific series on the subject at the NYRB wesbite.

Who Is A Millennial?

Can we please decide on who is a millennial? @sarahlyall says 21 – 39. Most others say 16 – 34. Which is it?http://www.nytimes.com/2016/05/16/business/media/trying-to-pin-down-the-mosaic-of-millennial-tastes.html?ref=media …

— @vivian

Given that generational labels are at best approximate and especially mutable around the edges it is of course impossible to fix a time frame on what age range defines millennials — let’s not even get into the tricky subject of who exactly we are speaking of when we use the word — but I will propose a rough guide to the characteristics common to the generations in order to better help you establish your place in our advertising-friendly cosmology.

• If your cohort is marked by self-obsession, a belief that you changed the world for the better and an inability to recognize that you got the best out of the economy, the environment and technology and you are going to die in comfort right before the negative effects that your reckless plunder on all of those things makes life unbearable for everyone who came after, you are a Boomer.

• If your cohort is marked by self-disgust, a belief that you never had a fair shot and an inability to shut up about how people used to talk to each other in person plus a vestigial obsession with shitty rock music from the Pacific Northwest, you are Generation X.

• If your cohort is marked by the belief that not enough people are making it about you, you are Generation Catalano.

• If your cohort is marked by self-obsession, a belief that you will change the world for the better and an inability to recognize that GIFs are not conversation, Tweeting is not marching, and quizzes that are almost comically transparent in their desire to turn you into a marketable commodity are not an actual ratification of how special you are, you are a millennial.

• If your cohort is marked by an astounding amount of potential and an already-notable lack of annoying self-regard you are whatever we would call the next generation. Unfortunately we are not going to come up with a name, because due to the way the Boomers fucked up the future for everyone you are going to spend most of your life running from fires and hiding from the killer robots that want to eat you. Sorry. Life isn’t fair (unless you’re a Boomer, in which case man did you really get away with one).

I hope that helps! But if you want something a little shorter so that you can share on social media here’s a brief takeaway that should settle the question at hand: If during the time it took to read this you started to get agitated about how long it had been since you last received praise from your supervisor, you are a millennial. Good for you!