Google's Self-Driving Cars Will Take Your Captive Body To An Empty Lot And Bury You Deep In The...

Google’s Self-Driving Cars Will Take Your Captive Body To An Empty Lot And Bury You Deep In The Ground After Running You Over

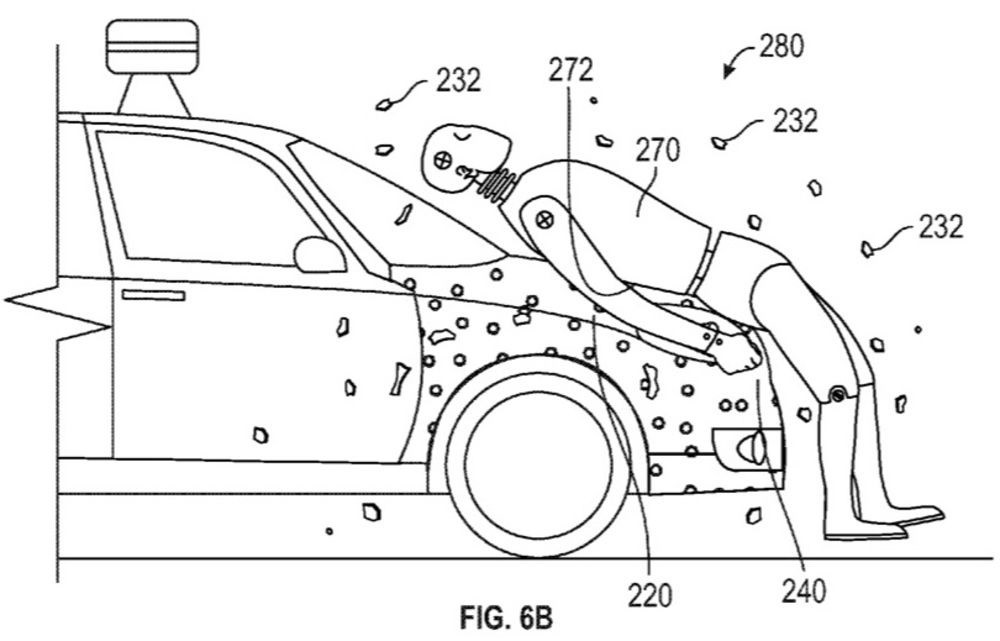

“Google has put through a patent for a new strategy to limit injuries when pedestrians are struck with vehicles. It operates roughly through the same method as flypaper. Using adhesive, the front of the vehicle will glue pedestrians to the car’s hood, effectively preventing them from taking a nasty tumble over the back of the car, or rolling off and onto the concrete.”

— This whole thing strikes me as a better metaphor for Facebook but I will accept that it can be applied fairly broadly.

Islands, "The Weekend"

If you have recently seen an older man shuffling slowly around town with earphones in, looking for all the world as if he is trying rather hard to keep from bursting into tears, then you have seen me listening to Islands’ “Umbrellas,” from Taste, one of their two new albums. Here is another song from Taste which I am happy to recommend since this one does not make me want to die every time I hear it — unlike “Umbrellas,” which is just a very sad, sad song. Anyway, get both albums, and enjoy. [Via]

A Poem By Dean Rader

by Mark Bibbins, Editor

Sitting in the Cell Phone Waiting Lot at the San Francisco Airport, Awaiting My Father’s Arrival, I Write a Poem on the Day of Prince’s Death

Every streetlight is a slightly different hue

of white the squares like the blank faces of robots

offer the Hondas and Toyotas idling in the lot something

like hope and yet I am thinking of all of the people on the planes

landing and taking off the twin miracles of arrival and departure

each of them singing “Take Me With You” whether they know

the song or not they are all singing: the pilots the flight attendants

the air traffic controllers the baggage handlers the men and women

with those colored sticks that look like little light sabers

guiding the planes out to the runway where everyone on board leaves

everyone behind and lifts once more into darkness

which is to say that the dead are tired of all the dying and yet it seems

never to stop the most recent plane crash was only seven

days ago when a Sunbird Aviation plane slammed

into the ground just before landing killing all passengers

when I fly I often think about what people do or say

seconds before impact no doubt believing they will somehow

survive that this can’t possibly be the end not me not now not like this

but not my father who is I believe asleep on the plane as the complex physics

of lift keep his steel machine of 75 tons buoyant in the blackness below

God’s feet and even though my father has never heard a song by

Prince Rogers Nelson he finds himself mouthing I don’t care pretty baby

as the jet is slapped by turbulence and he begins to fear for the first

time on this journey but mostly because he starts to believe that flight

is a metaphor for life and that just like dancing or loving or even

riding in an elevator we never know what determines if we fall

Dean Rader’s Works & Days won the 2010 T.S. Eliot Prize. The Barnes & Noble Review named Landscape Portrait Figure Form a Best Poetry Book of the Year. Suture with Simone Muench (Black Lawrence Press) and Self-Portrait as Wikipedia Entry (Copper Canyon) are forthcoming in 2017.

The Sharing Economy Is Only For People Who Can Afford To Not Share

“US adults who earn at least $75,000 a year are twice as likely to have booked trips on ride-hailing services (such as Uber) or rented rooms through home-sharing companies (such as Airbnb) as lower-income Americans, according to a new study from Pew Research Center…. Low-income Americans aren’t simply rare users of services like Uber and Airbnb — many haven’t even heard of them. While just 10% of people who live in households with earnings below $30,000 have booked trips with ride-hailing companies, nearly 50% aren’t familiar with them at all.”

Soundscan Surprises, Week Ending 5/12

Back-catalog sales numbers of note from Nielsen SoundScan.

Awl pal Ryan Adams put out a deluxe reissue of Heartbreaker, which also holds the top spot in vinyl sales this week, because of course. Adele’s first two albums are still selling like hotcakes, and Prince is still leading the charge with the top six spots. OK Computer got a little lift from Radiohead’s latest release, proving once and for all it is their best record. Except somehow In Rainbows got up there… Hmm. (Oh and for those of you wondering (me included), the definition of “back catalog” is: “at least 18 months old, have fallen below No. 100 on the Billboard 200 and do not have an active single on our radio.”)

7. ADELE 21 8,341 copies

10. ADAMS*RYAN HEARTBREAKER 4,820 copies

14. SHEERAN*ED + 4,378 copies

17. ADELE 19 4,010 copies

51. RADIOHEAD IN RAINBOWS 2,144 copies

68. WICKED ORIGINAL CAST RECORDING 1,839 copies

84. BEASTIE BOYS LICENSED TO ILL 1,681 copies

133. GOO GOO DOLLS DIZZY UP THE GIRL 1,312 copies

185. RADIOHEAD OK COMPUTER 1,101 copies

Photo: Flickr

Sam Ewens, "Clairity (Brass Version)"

Tomorrow is supposed to be both a) totally sunny and b) Friday, so if you can just hang on one more day everything will be slightly less awful than it has thus far this week. Anyway, this brass transcription of Nitemoves’ “Clarity” is so amazing that you don’t even need to know the original to enjoy it (but I will append it below in case you want to compare.) Enjoy.

New York City, May 17, 2016

★★ The day arrived humid and dim, not wet and dark, and nothing seemed to change as the hours went by. Invisibly it got warmer, then colder again. The small percentage chance of showers in the forecast meant, by afternoon, that some fractional portion of rain was falling, not even steady enough to be a drizzle. A man in a raincoat struggled to get out of a pedicab in a wholly unpicturesque block of Seventh Avenue. The chill and damp made the knees ache. The sun at last found a slit between the clouds and the roof of the neighboring apartment slab and came briefly straight sideways into the apartment, the golden hour compressed to one fleeting rectangle on the far wall and a glimmer in the reflective strips of the hanging backpacks.

Snapchat Explained

As an old person I find Snapchat strange and frightening. I find the people who use it even more disturbing, and I find anyone close to my own demographic who has embraced it especially off-putting (an under-reported story of our time is the one in which the new technologies of the era have somehow allowed people who should know better to delude themselves that they don’t seem like that creepy guy who was still hanging around the high school a few years after he graduated). But according to this piece in the New York Times — the instruction manual that helps old people learn what young people are doing — Snapchat’s appeal springs from its role as the place where you go when you still want to broadcast your brand but you need a break from the intensely competitive, high-pressure atmospheres of Twitter, Facebook and Instagram. It’s like a social media spa where you can let it all hang out without worrying about whether your digital presence has a hair out of place. I had no idea how draining this whole multiplatform identity maintenance thing is but it sounds exhausting. No wonder the kids today always seem tired. Anyway, I completely understand Snapchat’s appeal now and once I figure out the filters I will show you all a picture of my face as an ocelot vomiting rainbows, which is guess is the other big selling point of the app. What a remarkable age in which we live.

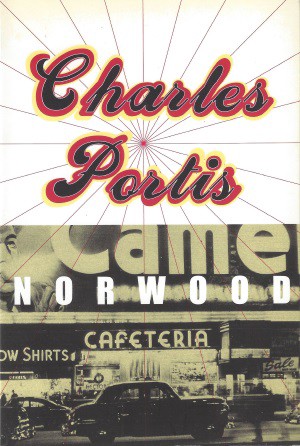

Appreciating Charles Portis

by Kyle Brazzel

A novelist can withstand only so many pieces about how he’s America’s most underappreciated writer until he becomes appreciated exactly enough. So, on the fiftieth anniversary of the publication of Norwood

, his first novel, let us now further appreciate America’s appreciated-exactly-enough novelist, Charles Portis.

Back when the appreciation was insufficient, Donna Tartt and Wells Tower were especially effective in tipping the scales, and Ron Rosenbaum’s cheerleading campaign in Esquire and The New York Observer had a huge impact in getting Portis’s novels back into print. Tom Wolfe expended a fair amount of words in “The Birth of ‘The New Journalism’” about Portis and his uncanny transition from newspapering to novel-writing, and that was back in 1972. Wolfe sat with Jimmy Breslin and Portis at The New York Herald Tribune, a paper, Wolfe recalled, that “was like the main Tijuana bullring for feature writers.” He watched Portis charge right out to become bureau chief in London, a move that reportedly put an end to a romance he had going with Nora Ephron (who would later compare him to Gabriel García Márquez.) Once Portis got to London, he met the Queen with a bright red cigarette burn on the end of his nose, the previous evening’s drinking bet gone wrong. The Queen probably did underappreciate him.

After a year of reporting stories on telephones he suspected were wiretapped, so frequently did the lines click and break, Portis returned to his native Arkansas, where he still lives, and found a typewriter and a remote cabin in the Ozarks. Here’s Wolfe, appreciatively agog:

In six months he wrote a beautiful little novel called Norwood. Then he wrote True Grit, which was a best seller. The reviews were terrific … He sold books to the movies … He made a fortune … A fishing shack! In Arkansas! It was too goddamned perfect to be true, and yet there it was. Which is to say that the old dream, The Novel, has never died.

Norwood is indeed a beautiful little novel. At 190 pages, it’s Portis’s slightest. It’s curious how much attention “The Birth of ‘The New Journalism’” pays Portis’s oeuvre, considering how little the novels (two at the time) follow the tenets of experimental forms or examine the subversive. Between the releases of the book and film versions of Norwood, Midnight Cowboy reset expectations for the rube-goes-to-New-York story, but the kinkiest thing Portis’s title character encounters on his pilgrimage from small-town Texas is a hot dog on a bed of baked beans, purchased at an Automat. If Portis was slouching into anything it was back into the utterly familiar, conjuring the fictional Ralph, Texas, a town of shade-tree mechanics and tented roller rinks, not far removed from the south Arkansas towns where he grew up, near the Louisiana border.

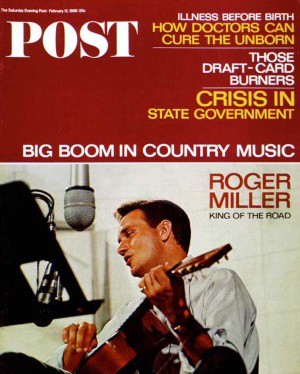

But Norwood is hardly autobiographical, letting alone that, like his creator, Norwood Pratt served in Korea. The experience doesn’t broaden Pratt’s world in the least, but it consolidates his ambition to get booked to sing on “Louisiana Hayride,” a sort of second string to Nashville’s Grand Old Opry. Portis knew well the ways a twangy country song could play on a serviceman’s self-pity. “There were few rifle companies in that war without a wind-up record player and a well-worn 78 rpm record of Hank Williams’ ‘Lovesick Blues,’” Portis wrote in a Saturday Evening Post report on Nashville’s country music scene, published in 1966, the same year as Norwood.

By the time Portis sat down to write Norwood, the post-war boom in novels exploring white-male ennui was on the decline. But Portis went off any recognizable narrative grid; his sympathies lay with characters who never considered rebellion. Norwood Pratt begins as a discharged Marine on the way to becoming a mechanic — a rung where, despite his fantasies of country-music stardom, one expects him to stay.

“A lot of his people would now be called slackers, I think,” Calvin Trillin told me of the Portis coterie. “They didn’t want to rise in the firm or anything like that.” (Trillin did detect something aspirational in Mattie Ross, which is why he read True Grit aloud to his daughters.)

“Norwood is simple,” said Roy Blount Jr., another fan. “It doesn’t go out of its way to be funny, or even to be a story. It doesn’t raise any big issues other than the main ones: getting paid, doing right, finding somebody to be with.” Blount’s favorite story of the Portis novel is of how a friend sent his girlfriend upstairs with a copy of Norwood to read before clarifying how he felt about her. When he heard her laughing, he knew they had something.

Call it The Norwood Ultimatum — the challenge to find enduring worth in a volume Wolfe and Blount damn with diminutive praise. This has to do with what we now call “narrative stakes,” a phrase it’s unlikely Portis gave any consideration. Ray Midge sets out to get back his wife and his prized Ford Torino, not necessarily in that order. Mattie Ross sets out to avenge her father — a mission that is simply only in that it is primal: blood simple, to put it in terms the Coen Brothers, responsible for the superior of True Grit’s two film adaptations, could appreciate.

When he started publishing novels, Portis had traveled the world and become a star at the Tribune, for which he continued an area of coverage he began at Harry Ashmore’s Pulitzer-winning Arkansas Gazette: the country’s ongoing civil-rights struggle. Wolfe was especially tickled by the story of a press conference during which Portis repeatedly addressed Malcolm X as “Mr. X.” In Portis’s telling, use of the honorific was attributed to his own Southern sense of decorum. In Wolfe’s, it was insouciance: Portis reacting to Malcolm X’s insistence that nobody in the room call him merely “Malcolm,” because he “was not a dining-car waiter.”

In his curiosity about the world and his responses to what he saw as its absurdities, Portis shared more with True Grit’s 14-year-old heroine Mattie Ross than he did with Pratt, his debut creation. (By the novel’s end Mattie understands that she is “a woman with brains and frank tongue.”) Ray Midge, the protagonist of The Dog the South, also seems to share more Portis DNA than Norwood. A newspaperman, he becomes so excited reading historical accounts of Hannibal and de Soto he has get up and pace the room to catch his breath. Meanwhile Pratt is positively anti-intellectual; while a bohemian New York paramour reads aloud to him from “something called The Prophet,” he clips his fingernails.

All Pratt seeks is seventy dollars owed to him by a fellow Marine. (No sooner has he gotten it back does he loan fifty of it to a downtrodden former circus performer billed as “the world’s smallest perfect man.”) Indignity upon indignity befalls him, not least of which, it must be noted, was his own movie version, released in 1970. Larry McMurtry’s The Last Picture Show, another novel of small-town Texas life marking its fiftieth anniversary this year, got Peter Bogdanovich in moody black-and-white. Norwood got Jack Haley, Jr., a director best known for show-business documentaries like That’s Entertainment! and being Liza Minnelli’s second husband.

Portis’s singular achievement with Norwood has nothing to do with narrative scope or depth of feeling, but in establishing and sustaining tone in a comedy of manners where no two characters subscribe to the same set of them. This, in particular, seems to have tripped Haley up. (Though casting the country singer Glenn Campbell as Norwood Pratt didn’t help.) In an exchange at a roadside diner, a cheerful waitress asks Campbell, as Pratt, for his order. “A cup of coffee, I guess,” he replies. “I’ll put in my own cream.” Campbell adds this last bit, a throwaway in the scene, with a kind of sheepish pride, like a little boy who’s pushed the elevator button by himself. But here’s how it goes in print: “Norwood snapped at the counter girl for putting cream in his coffee. She said she didn’t know where he was from but if you wanted it black you had to say so. He told her he was from a place where they let you put your own cream in your coffee. From little syrup pitchers with spring lids.” The highly specific irritability Haley scrubbed from Norwood the movie may be another reason its source material can feel underappreciated. But, that’s entertainment.

Ultimately, Portis gave Norwood Pratt one dignity otherwise allowed only to Mattie Ross: a sense of closure from across the ages. Ross delivers her coda (“time just gets away from us”) at the end of True Grit. Norwood’s didn’t arrive until 1996, in a short story Portis produced for The Atlantic. (Titled “I Don’t Talk Service No More,” it’s reprinted in Escape Velocity, an essential anthology for the Portis completist, edited by Jay Jennings

.) Portis doesn’t name the narrator, so it takes a little magical thinking to see him as Norwood Pratt. But not much. He’s a Korean War vet, confined to an institution, determined to relive a definitive raid by breaking into the library each night and telephoning former members of his squad. The library is behind a locked door; the telephone is in a locked drawer. “It’s not so bad if you have the keys,” he tells one of his midnight commiserators. “For a long time I didn’t have the keys.” Fifty years on, Norwood isn’t going to give you any keys, but it does reassure with the sense that everybody fumbles with the locks.