New York City, June 2, 2016

★★★★★ What blew in through the lobby doors felt like air conditioning at first. Out in the street, it assumed the character of the breeze over the deck of a sailboat. A venture outside for iced coffee, passing through sun and shade, came back with hot coffee instead, because it was so feasible an option. The day demanded nothing one didn’t already want. High windows threw blinding reflections into the shadows. Leaves tossed in the clear late sun.

How To Let Go

Planning a fall and surviving.

For a brief span of about one spring, I was obsessed with learning how to fall. This is not a metaphor; when I say I was learning, I mean that I typed “how to fall” into a search engine and discovered the surprisingly robust world of YouTube falling tutorials. And when I say “obsessed,” I mean, I fell. I bruised. I got back up and fell again.

To successfully fall requires a certain disposition, a willingness to often look like a fool while doing so. This was the point of many of the videos: “Is there a limit to how much comedy you can do?” a professional clown sans grease paint asked in one, before crumpling like a flower to the floor. Others were more serious: a British skateboarder advised his audience to never catch oneself while falling, lest they break a bone (“Watching this with a broken wrist lol,” went the top-voted comment on this one). This contradicted the acrobat’s advice — the opera fall he flung himself backwards into gets its name from the Peking opera, and involves using the arms as a means of diffusing force from the spine. The spine, and how easily one could paralyze or kill oneself with one misplaced fall, was a concern in all of them; “How to Fall to Your Death and Not Die!” went the cheerful title of what turned out to be a guide to amateur special effects.

I did not want to die, so I kept watching. Over the course of my obsession, I learned to shift my weight to my side, to swing my legs above my head in one spectacular, showy pratfall; I learned also that I was uninterested in learning jiu jitsu, impersonating Charlie Chaplin, or figuring out the one weird trick behind falling down a flight of stairs. The idea of context, of falling for a greater purpose — a stunt or a laugh or some other kind of performance — for some reason, this depressed me. My interest stemmed from something more ephemeral; I practiced in my bedroom, refusing to let anybody watch. Call it curiosity, maybe — I wanted to live and re-live that moment when the body is flung into motion. That tension. That flight.

Falling occupies an interesting cultural space. In summer camp, we fall backwards into the tender hands of our classmates in order to build trust; there’s no real evidence that this is, in fact, the outcome. There’s the less literal wordplay of falling, too — falling asleep, falling in love, falling from grace. Then there’s the Fall, when in Christianity Eve ate the apple and fucked it up for the rest of us. Or there’s that feeling of falling that sometimes occurs just before we begin dreaming, when the body jerks itself awake before starting the whole process over again. These are called hypnagogic jerks, and no one’s sure where they come from.

Most falls are an accident, someone tripping over a rock or slipping backwards on a patch of ice. Planned falls, once you actually know what you’re doing, are more dignified; there’s a level of control necessary even when losing control of oneself to gravity. It’s a kind of self-effacement, a Zen-like exercise in giving yourself up to forces beyond your control. The best pratfalls exude this sense of melancholy, even when they’re begging for a laugh. As funny or technically accomplished as Buster Keaton’s falls could be, there’s also a beauty to them, an artfulness that Harold Lloyd and Chaplin lack. They feel, occasionally, like Sisyphus’s struggle, or saints tossing themselves through some obscure form of torture in order to gain knowledge of the divine.

“I have always been fascinated by the tragic,” the Dutch performance artist Bas Jan Ader said in a 1972 interview, when asked about his own falls. “That is also contained in the act of falling; the fall is failure.” In a series of videos made during the early seventies, Ader filmed himself falling from a tree, falling from the roof of his California home, and falling into a city canal while bicycling through Amsterdam. Each fall is brief — one lasts barely over a minute — and lack any kind of rhyme or reason. Instead, it’s falling for falling’s sake.

In “Broken Fall (Organic),” Ader hangs from a tree. Over the course of the minute-long video, his thin body swings and sways, looking not dissimilar from the tree trunk behind it. The moment is tense; we know what’s going to happen. When it does, though — when he loses his grips and falls, with a splash, into the pond below — it’s still a shock. At the video’s beginning, there’s a chance that the inevitable won’t happen; at the end, it already has, and lasted no more than a second.

Is it unfashionable to wish for transcendence? The danger with vulnerability is that sometimes it can lead into affectation, a pose of sadness that does little to reduce the barriers between a person and the world surrounding them. We’ve all had the too-drunk friend crying over problems that are interesting only to themselves. But drunks somehow always manage to avoid injury when falling — it’s the lack of self-consciousness. At a certain point, their mind ceases to be, and muscle memory takes over.

How lovely, to successfully abandon the buzzing of one’s own thoughts. This, I realize now, is why I was so unsuccessful during my brief obsession — I’d always catch myself before my feet left the ground. Falling requires a willingness to let go, quite literally — and alas, I’m too tense, too anxious. Sometimes my body shakes from how tightly I hold myself upright. As though I were afraid to slip.

Too bad. That moment when feet meet air, when the mind flattens into nothing and the body takes over, more concerned with gravity than the trajectory of one’s own worries — that moment sounds like heaven. Some of us will never achieve it. There’s a freedom to that moment: no voice, no ego, no I. There are rules that must be followed: what goes up must come down. A body in motion stays in motion, unless acted upon by an unbalanced force — and thwunk, there it is. There is the ground. There is reality. There is the simple fact of existing, of being alive.

Rhian Sasseen’s work has appeared in Aeon, Pacific Standard, the Los Angeles Review of Books, and others

Spring and Thompson Streets, New York City

This week you were walking west on Spring very fast with your bags jouncing against your sides and at least seven things on your mind. If I had to guess, I’d say your name was a monosyllable. Your parents, I think, gave you something longer and fancier, but you feel more yourself with a three-letter abbreviation. You appreciate the way there’s a kind of neutrality to it. Sometimes, because of your monosyllable name, people think you’re a dude before they meet you and you kind of like that.

It was close to the place where you can queue up to buy the thing that frankensteins a French breakfast pastry with a donut, in a name that people love to hate to say. Which is maybe why they stand in line so long to buy one: so they get to use the word a lot when they tell their friends how it did or did not live up to expectations.

You did not have time for that shit. You were late, I’m pretty sure. You just had a lot on, but you were dealing with it, because that’s what you do. I was late too, but I was walking slowly and not dealing with it, too morose for the person waiting five blocks away. Being this slow then, I had ample time to see your t shirt as you strode past. In black on white across your big boobs it said CUERVO NO CHASER and in a snap I heard the way she makes that word a flourish or sound effect — ch’ssahhh — a pop and a hiss like a soda can cracked open, and my smile did too — crack, I mean — and I only know this because in that moment your attention and your gaze, which had been way off in the future and urgency of a to-do list, popped into surprised focus on me, feeling that smile. The best thing was the tiniest fraction of a second of confusion, why’s this bitch smiling, before you remembered what t-shirt you were wearing, what your chest said. Your smile back was both reluctant and inescapable, a graceful kind of grudging, because you still had all the stuff on your mind, but I’d seen your t shirt and you’d seen me and Beyonce was between us. Brief and wry, your smile said, said yeah, I go off, I go hard, et cetera et cetera.

Two blocks on, I considered the fact that you had chosen a lesser known lyric, a plain product placement, really, and I respected you for it. Because your t-shirt could have just said “I SLAY” and I don’t think I would have smiled.

Hermione Hoby writes about culture for the Guardian and others.

The Translation Altercation

There’s a lot going on over which words are the right ones.

The New York Review of Books has had some fascinating stuff of late on the difficulties associated with translating works of fiction into English. The bulk of the material comes from Tim Parks, but now Janet Malcolm — a writer who is not unfamiliar with controversy when it comes to faithfully representing the words of others — steps forward to eviscerate Richard Pevear and Larissa Volokhonsky, the current popular favorites in the Anglicization of great Russian works. (A revised version of their The Master and Margarita translation is out now in celebration of that novel’s 50th anniversary.)

Malcolm’s dissatisfaction with the pair stems from her concern over this question (which is at the root of most of the arguments about translation):

Whose interests should the translator serve? Those of the reader of simple wants, who only asks of a translation that it advance rather than impede his pleasure and understanding? Or those of the more advanced (or masochistic) school who want to know what the original was “like”? I am speaking here of translations of fiction. Poetry and humor are untranslatable in the view of some readers. But surely novels can be successfully translated. The basic myths they transform into stories of their time belong to all cultures and can be retold in any number of languages.

What’s the answer? Fuck if I know. I have a hard enough time understanding English that was written in English. But it seems at least like the right question, and I am more inclined to side with Malcolm (whose case against Pevear and Volokhonsky mostly rests on evidence from their adaptation of Anna Karenina) here. In any event, who knew one of the most exciting controversies of 2016 would be about translation? Not me! (For a less contentious look into the shockingly combative world of translation, Liesl Schillinger’s series of interviews with translators is about as enjoyable as people talking about writing can be.)

Axel Boman, "The Chains of Liberty"

Axel Boman, “The Chains Of Liberty”

One of the few benefits of the rapid reduction of American intelligence is that its prevalence and volume is so relentless that after a while you find fewer outright objectionable examples of the massive ignorance all around us to trip you up; it’s just always there, like the air or the trees. You might not like it, but at least it’s not as shocking anymore, and you can go about your day more easily when you no longer need to pause and look around you and scream, “Sweet mother of fuck, am I the only one left who sees just how shit-all stupid this is?” as frequently as you once did. I am developing a theory that our gradual acceptance of this omnipresent imbecility is, in some ways, making life easier. Take, for example, the perception of time: It used to be that a four-day week somehow felt even longer than the usual Monday-to-Friday routine. But this week practically zipped by, and I think it’s because we’re all so acculturated to the constant barrage of idiocy that was once so toxic and trying that we almost float above it now. I mean, yes, it will all end badly, but at least it will be a smooth ride until we come to that jarring and terrible finale. In any event, the weekend is here and it wasn’t even that hard to get to. Thanks, dumbassness! Here’s a song to help you through the last stretch. Enjoy.

New York City, June 1, 2016

★★★★ Already on the walk to school the sun came in hot under the scaffolding. The east was too bright to look at. The breeze as strong and refreshing on the cross street and stronger still out on Broadway, where it reversed direction from one end of the block to the other. The heat was strong but easy; the smell cooking up around a corner storm drain was remarkable without being overpowering.

Jam Jockeyed

Why You Can’t Escape “Seven Nation Army.”

In the winter of 2012, Deadspin published a meticulous reconstruction, written by Alan Siegel, that detailed the transformation of The White Stripes’ “Seven Nation Army” from sound-check noodling into arena anthem. Siegel traced the burgeoning U.S. American use of the song’s main riff as a European-football-style chant to, well, a European football match.

In 2003, Belgian soccer fans in Italy, there to watch Club Brugge K.V. against A.C. Milan, overheard the song in a bar before the game. The Belgians started singing along to Jack White’s syncopated, circular riff, continuing as they headed through the streets and into the stadium. (That is, they weren’t so much singing the song as they were emulating its guitar part; no lyrics necessary.) After Club Brugge defeated Milan, “[t]he song traveled back to Belgium with them, and the Brugge crowd began singing it at home games,” Siegel wrote. “The club itself eventually started blasting ‘Seven Nation Army’ through the stadium speakers after goals.”

From there, the riff-cum-chant gained a foothold with supporters of the Italian club A.S. Roma, and then with the Italian national team — who would go on to win the 2006 World Cup. Siegel identified a public radio story and the ministrations of marching-band arrangers as the means by which the song leapfrogged into U.S. college sports, first at Penn State, then at Boston College, then Ohio State and Michigan and everywhere else. It was only a small step into North American men’s pro sports. “Seven Nation Army,” the Deadspin headline declared, had “Conquered The Sports World.”

Setting aside the fact that what “Seven Nation Army” had conquered wasn’t so much the world as it was the North Atlantic, what no one could have known then was that the tune was still on the ascent. Forget the military metaphor; “Seven Nation Army” didn’t advance by siege and flanking maneuvers. It spread like a weed.

Which is how, on Saturday night at the Chesapeake Energy arena in Oklahoma City, it ended up hoarsening the throats of Thunder fans as they urged on their team’s doomed attempt to hold off a surging Steph Curry and the Golden State Warriors in the N.B.A. Western Conference Finals.

If “Seven Nation Army’s” leap from record to grandstand began in one Milanese bar with a single pack of Belgian diehards, its proliferation in North American men’s pro sports, like the invention of calculus or the telephone, is a case of multiple discovery.

Early adopters of “Seven Nation Army” in the U.S. included the N.B.A.’s Milwaukee Bucks, and the N.F.L.’s Detroit Lions and Baltimore Ravens. The Bucks’ special cheering section called Squad 6 — dreamt-up and financed by the Australian center Andrew Bogut, who now plays for the Finals-bound Warriors — may have been the first to chant it as a signature. This message board thread, from 2009, captures the very moment Bucks fans hatched the idea. In an email, Johnny Watson, Bucks Director of Live Programming and Entertainment, confirmed that the team had played the song as early as 2006, using it as an invigorating entr’acte between the third and fourth quarters of home games.

Squad 6 members seem to have known the riff and routine from European soccer. In the the message-board thread, one member writes that he sent Bogut a popular Italian remix called “The Concert” by M@d; it was reportedly well received. Bucks fans were also aware of college football’s growing penchant for the song, especially in the midwest, mentioning Ohio State as a model in particular. Likewise, Detroit Lions fans probably drew on the “Seven Nation Army” tradition established at the University of Michigan.

Ahead of the 2011–2012 hockey and football seasons, the song extended two other tendrils into North American pro leagues. The N.H.L.’s Ottawa Senators chose an EDM-infused version as their goal song, and, in what would turn out to be a pivotal event, the Baltimore Ravens adopted the chant by fan vote. “I lobbied hard for ‘Seven Nation Army’ to be in the mix, because I had seen it work in Europe. So I thought, ‘if we bring this to the states it could be really cool,’” Jay O’Brien, Director of Broadcasting and Gameday Productions for the Ravens, told me. O’Brien had learned the song while studying abroad in Rome.

The Ravens debuted their loudspeaker-edit of White’s riff on an occasion shot through with emotional significance: a home opener, held on the tenth anniversary of 9/11, played against their arch-rival, the Pittsburgh Steelers. As the Ravens bullied their way to a 35–7 victory — avenging the playoff loss that ended their season the year before — fans, players, and coaches embraced “Seven Nation Army” in real time. “John Harbaugh [the Ravens’ head coach] and the players were up on the screen while we were playing the song, and they were into it, so the fans got into it,” O’Brien said.

“If we didn’t have that game on that day with that song, I don’t know if it would have happened,” said O’Brien, “I had the time of my life at that game, and I think everybody else did, too.”

The Ravens’ adoption of the song had two important consequences. First, the chant soon crossed Martin Luther King, Jr. Boulevard to join the Orioles at Camden Yards, granting it a perch within Major League Baseball. This kind of exchange wasn’t unprecedented in Baltimore, whose althetosphere is sometimes branded “Birdtown” for the weird avian synergy of the Ravens, Orioles, and — if you’re of the patrician class — NCAA lacrosse’s Johns Hopkins Blue Jays.

The second — and decisive — consequence was that Baltimore’s raucous version followed the team all the way to their 2013 Super Bowl victory. A few months later, the Miami Heat would claim the N.B.A. title after a season in which the song accompanied the home court introduction of their lineup, led by LeBron James, Chris Bosh, and Dwyane Wade. “Our fans had been chanting the ‘Seven Nation Army’ chant for a number of years kind of organically. And we thought it would be a great opportunity,” Heat Executive Vice President and Chief Marketing Officer Michael McCullough said, “so we pursued the rights to sync the song to a video.”

The introduction, and “Seven Nation Army,” became Miami trademarks. But trademarks can also be targets, as the Heat learned when San Antonio fans trolled them with the chant after the Spurs took game three of the finals, 113–77. It wouldn’t be enough to stop Miami, though, who’d go on to win the series in seven games. If winning is the whole thing — and it is — then 2013 was “Seven Nation Army’s” sporting high point.

Meanwhile, in college sports, the riff had spread to a point of utter diffuseness. As Chris Strauss of USA Today wrote, citing Michigan, Ohio State, and Penn State, “What good is it if three of the oldest rivals in the Big Ten are all using the same exercise to fire up their stadiums?” A song adopted on both sides of a rivalry loses meaning — it’s just noise.

Internationally, “Seven Nation Army” remained the go-to soccer anthem; during the Euro 2012 tournament it was the standardized goal song. I was in Spain during their team’s final-round victory over Italy, but I don’t particularly recall the crowd singing along as it blared over the loudspeakers. The song of the summer there wasn’t “Seven Nation Army,” but rather Sak Noel’s unbearable “Loca People.”

However indifferent Europeans had grown to it, the infestation continued unabated back in the States. Increasingly, chanting “Seven Nation Army” became a referent-less intensifier, a vehicle of pure affect, like “Rock and Roll (Part Two)” had been before it. (No doubt the revelation that the musician behind the latter was a serial pedophile sped the takeover along; The NFL issued a ban on the infamous “na na na na na—hey!” song in 2006.)

In June of 2013, EA Sports announced that a “Seven Nation Army” chant would feature in the game NCAA Football ’14 — thus completing the song’s cyclical transformation from commoditized sound into communal performance and back again. In November of the same year, 19,211 fans of the New Jersey Devils elected it the team’s new goal song, but only after the team nixed the old one, “Rock and Roll (Part Two),” because of their fans’ habit of using it as a springboard for “you suck!” chants.

A sure sign that “Seven Nation Army” had passed over into total cultural ubiquity, shedding any remainder of specificity, came in 2015, when the Foo Fighters performed the song at Boston’s Fenway Park along with frontman Dave Grohl’s orthopedic surgeon. To be clear, that’s a band that’s not the White Stripes, singing a song that’s only incidentally about orthopedics (“And the feeling coming from my bones says, ‘Find a home’”), with a doctor, in a ballpark known for a Neil Diamond song.

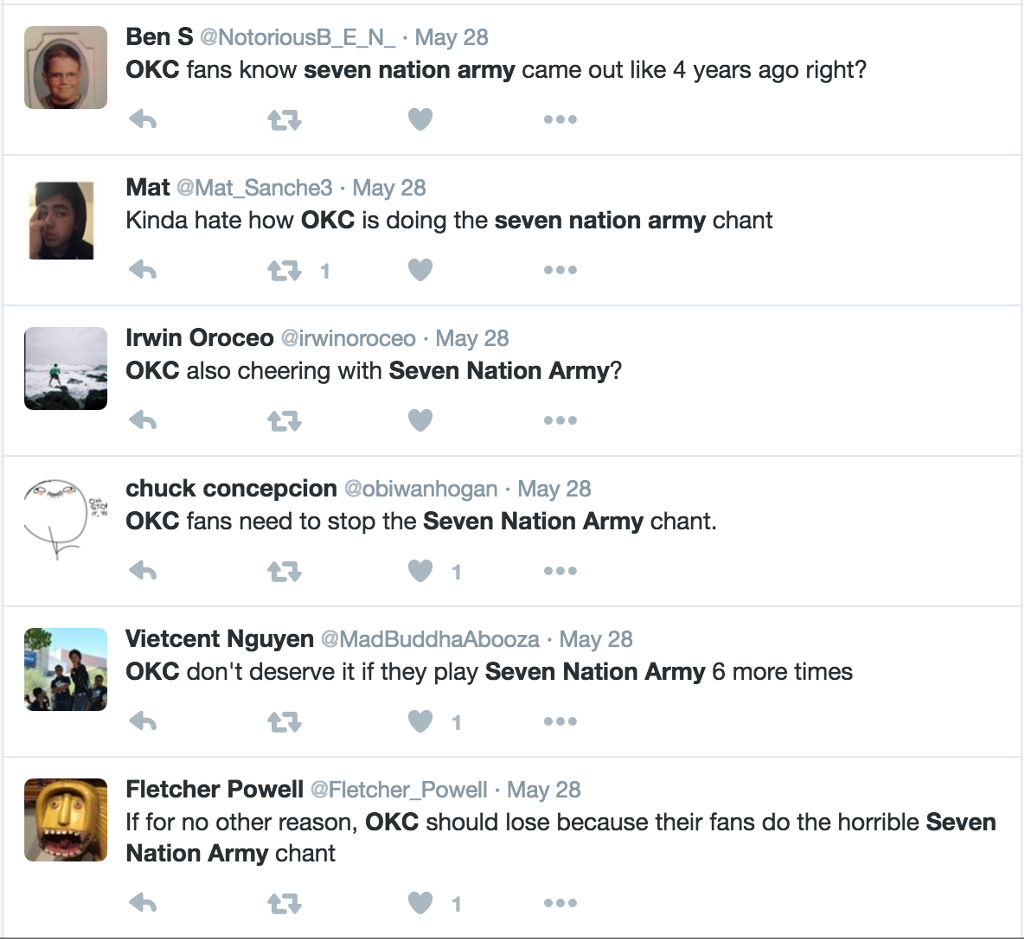

I n April, Sean Gentille of The Sporting News dubbed “Seven Nation Army” the “best possible example of a truly great song ruined by overuse.” Already in 2014, a blogger covering the West Virginia University Mountaineers for SB Nation counseled moderation in the use of the song at home games. Last Saturday night, during the Thunder-Warriors game, MTV News political writer Ezekiel Kweku tweeted:

Basketball, over the years, has made me come to hate Seven Nation Army

For his part, Jack White has embraced the phenomenon, calling it “the greatest thing that could ever happen” for a songwriter, and likening the song’s embrace by sports fans to the processes of “folk music.”

Instead, it’s maybe more accurate to hear “Seven Nation Army” and the sports empire it built as global capitalism all the way down. Originally recorded on a label founded by the mogul Richard Branson, heard by Belgian soccer fans in Italy because of globalized distribution networks, and passed from stadium to stadium in the United States thanks to an efficient legal framework that allows teams to secure the use of millions of songs by purchasing blanket licenses from just three organizations, the song couldn’t have spread as it did except under late capitalism. And, of course, deep in the foundation of The White Stripes’ blues-rock style rests the commodification of African-American music that was so much a part of accumulating the music industry’s financial clout in the first place.

Though none of this means that Jack White is wrong in every case to think that his song can feel like a bit of folk culture. Maybe in some pockets — for the supporters of Club Brugge, say — chanting its seven notes still feels specific, like something that binds together you and actual people you actually know. Maybe in some places it continues to affect and signify on a more human scale. Maybe it’s not done just yet. That’s the suspicion of the Ravens’ Jay O’Brien, anyway: “People have mentioned over the last couple years, ‘should we stop using it?’ But I think our fans would do it anyway.”

Brian Barone is a graduate student in Boston. He co-hosts the music podcast Tuner.

Sperm Selected

Shopping online for your baby’s dad

“I know women who chose a donor for his height, or to get a different race from their own, or because he looks like their existing children. I have friends who bought each donor à la carte, trying a different one each time. Like my path to parenthood, I found my donor through the process of elimination.

I rejected businessmen, who made me picture cheap loafers. Musicians made me think of flakiness and pot. Baptists were too credulous. I wanted an “open” donor, one my child could contact later, so there was no Dickensian mystery at the center of his or her life. I didn’t want one who was married or had children of his own. (‘So conceited!’ one friend summed up.) I wanted one with reported pregnancies; my eggs were both aging and untried. And, with my Masters in poetry, I wanted logic: mathematicians, scientists, engineers.”

— Awl pal Lizzie Skurnick’s story of how she chose her sperm donor is sweet and funny and won’t make you feel terrible about everything, unlike so much other stuff you see on the Internet these days.

A Poem by Rick Barot

Virginia Woolf’s Walking Stick

Unless you are too sensitive or being affected, you don’t cry

over a thing in a museum, knowing what’s there

is already dead. But there I was, in grief, because when I bent

to the glass case I saw the walking stick

she left behind on the river bank before she walked in

and sank and died.

I hadn’t known the object would be there,

it was among other objects in an exhibit of writers’ artifacts,

a black sturdy thing that might have been owned

by anyone but was owned by her, the last thing of this world

she touched before she touched the stones

that would go into her pockets, the stones which

were things of another world.

The shock of the walking stick was like and not like

the first time I read something she had written,

when I sat at a library carrel in college, cleared it of the books

someone had left there, and found a volume of her diary

among them. This led to the four other volumes,

then to her actual books. This led to a voice, a way of thought

and being, a way of knowing the ordinary

and the profound, that seemed my voice too,

despite the differences that should have made the affinity

impossible — the years between us, gender and class

and race. But there we were. Looking around

at the things that surround me, I have come to believe

that the test of how well a thing is made

is to look at the places where its parts come together —

joints, seams, corners, folds. I know it’s a violence to sense

and sequence, but I’m thinking now about sitting with him

in the car in the hours before dawn,

reading aloud the ugliest parts of Wenderoth’s Letters to Wendy’s.

The parts where the speaker does things to Wendy.

The part where the speaker fucks a Frosty. Back and forth,

by the dim gold light of the car, parked on the street

outside his apartment building, reading, laughing,

breathing. I was in love with him and he was in love

with someone else. This is what we hadn’t talked about

all night. Earlier, we had driven to a hill

that looked down on the enormous city, lit up

like a circuit board in the overall mechanism of the dark.

We stood, hands in our pockets, shrugging in the summertime

cold of a city by the ocean.

The wind was all the talking there was, and then

we were walking back to the car.

This was some time ago. And I don’t seem to understand

any more now than I did then, the hill,

continually whirled by the wild air, while still full

of original feeling, now empty of people and incident and time.

Rick Barot’s most recent book is Chord, which received the UNT Rilke Prize, the PEN Open Book Award, and the Publishing Triangle’s Thom Gunn Award. Barot lives in Tacoma, Washington and directs The Rainier Writing Workshop, the low-residency MFA program in creative writing at Pacific Lutheran University. He is also the poetry editor for New England Review. In 2016, he received a poetry fellowship from the Guggenheim Foundation.

The Poetry Section is edited by Mark Bibbins.

The Avalanches, "Frankie Sinatra"

A new record from the Avalanches, plus Danny Brown!

I did not love Since I Left You the way some other people loved Since I Left You, but I liked Since I Left You just fine. I love this song though. Maybe it is because Danny Brown adds magic to everything. Anyway, enjoy. There’s more about the new record here.