The Mangenue

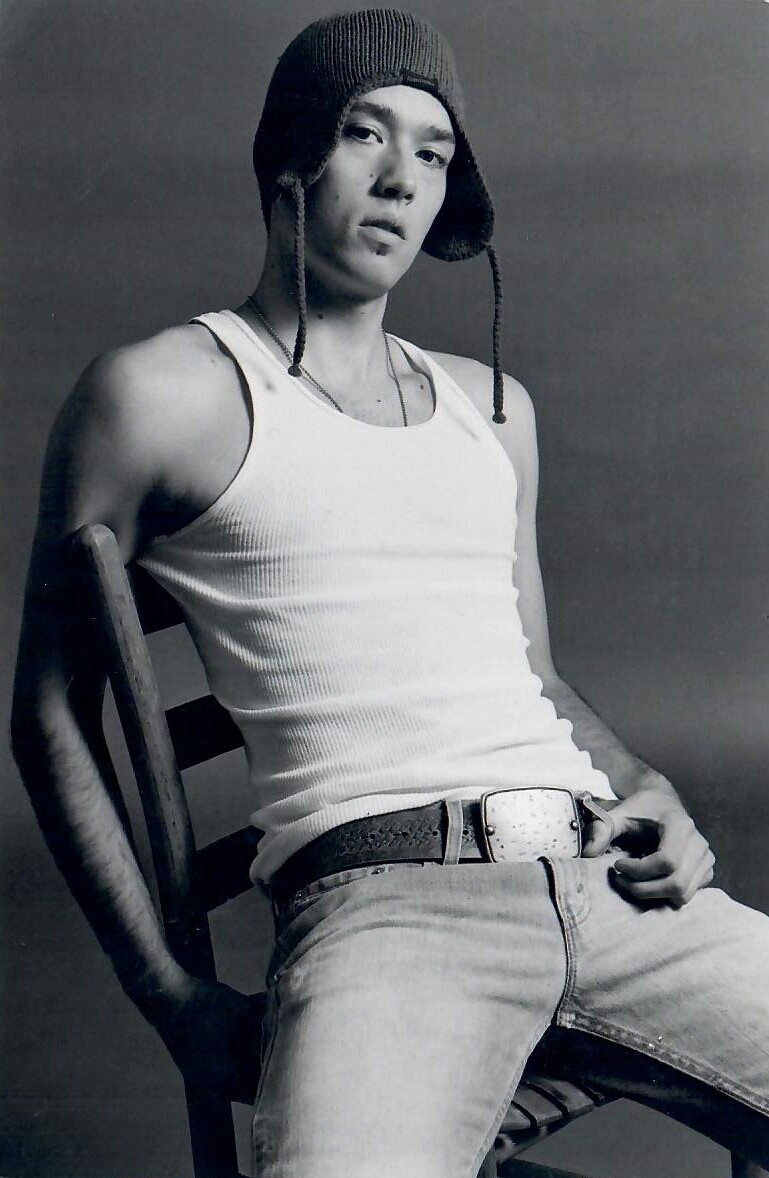

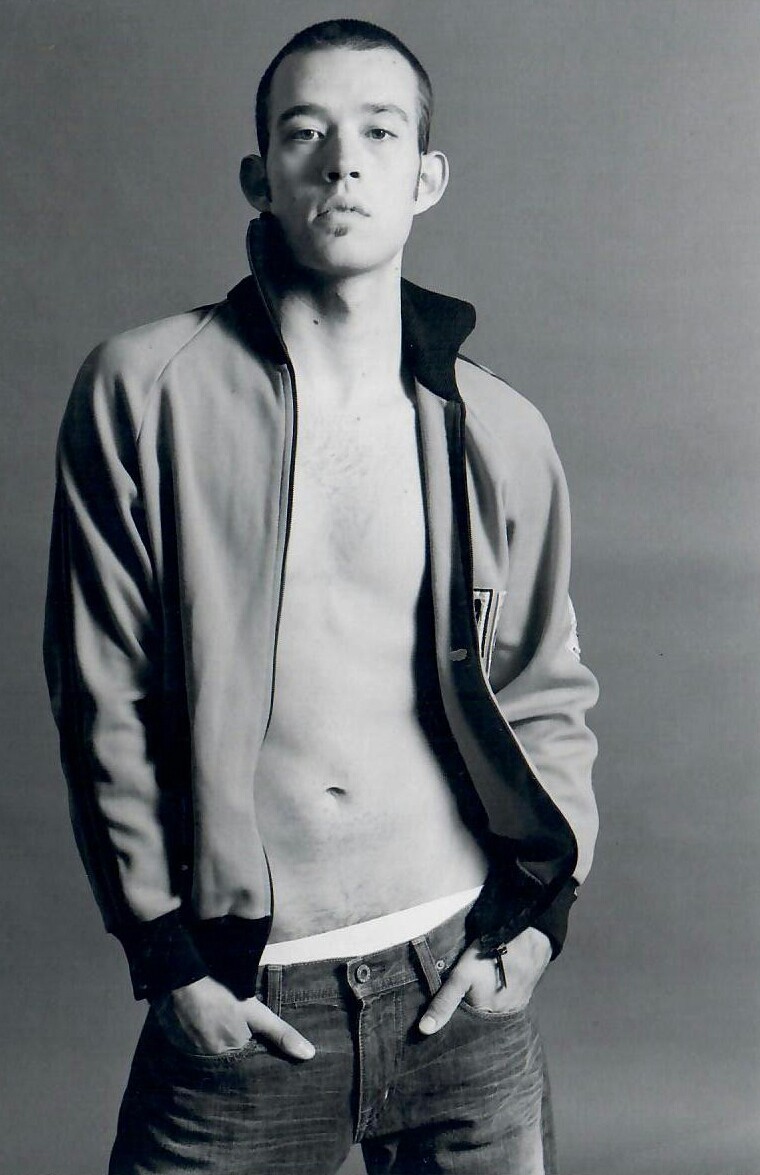

man-jǝ-nü n. aspiring male model, naif—me in the early 2000s

I’ve been avoiding Midtown West for a while, and now I remember why. The Mangenue is everywhere. The Mangenue is a simple young soul who moved to the big city with aspirations of stardom, banking on nothing more than his good looks and a virile young body. He cuts in front of me in line at Starbucks, sizes up sidewalk competition with looks of superiority, and tirelessly speaks to the caloric benefits of drinking vodka sodas. Though he has no formal training and hasn’t starred in a relevant stage production, The Mangenue assumes that because the peasants in his suburban hometown like all his pictures on Instagram, he is certainly already famous. And I know The Mangenue all too well — because I used to be him.

In 2003, I’d been living in London after leaving college in Seattle, determined to make my mark as a male model. After intensive research, I decided the only agency for me was Storm Model Management — the prestigious company that found and represented Kate Moss. Storm was the third-ranked agency in London, and its founder, Sarah Doukas, was well known for turning many of her models into legitimate working actors. I wasn’t sure if I would be a break-out actor, or break-out male model — but I knew Sarah would make me a star.

Before leaving, I stood in the mirror with my face slightly turned to the left. Which side would I display to the agency? I considered my right, which features a hooded eyelid and rounded nose tip, making my face appear soft, dewy and full. Or I could go with the left, with a sharper nose tip, making me appear striking, wise, and slightly more severe.

I was feeling aggressive, so I went with the left. Everywhere I walked, I would align myself so that store fronts would be to my favored side, and I could stare at my reflection in the window as patrons watched me walk by. I strutted through the front door of Storm with the confidence of Naomi Campbell carrying a handbag made from the soft hind of a former personal assistant. At the front desk, I slapped my pictures down in front of the receptionist.

“I’m here to show my modeling portfolio,” I said. She nodded while pawing through the pages, and landed on an image of me in low-rise jeans — my chest and a slight tuft of pubic hair exposed. I stood confidently, waiting for her to praise my effortless sex appeal.

“How shall I say this, darling?” she said with a lifted brow. “You’re in a jewelry store.”

The next day, after realizing that Storm Watches wasn’t looking for a new male hand model, I was relieved to find the real Storm Models. I assumed I’d be surrounded by chic women in all black, the men dressed in double-breasted suits and facial hair groomed for the early twentieth century. Instead, I sat alone in a brightly lit corridor, staring at the fresh pair of witch boots I had purchased in an exclusive Spanish boutique called Zara. A half hour later, a chipper young woman named Julie came through the door with my portfolio in hand.

“Hello, James. Your pictures are really good — and we carefully considered you. Unfortunately, we feel you’re too commercial for Storm.” She said the word commercial with an extra British snobbishness.

“Thank you for considering me,” I said in a daze.

“Have you tried looking for work in L.A.?”

No, but I was intrigued. I had never considered starring in my own TV commercial before! I used to love the girl from the Mentos ad that ripped her dress in half when she needed a quick fix. And didn’t that actress end up on “Dawson’s Creek?” Commercials — that was it! Julie must have thought I had something special in me that could sell a product in thirty seconds.

Three more agencies in London all had the same suggestion: I was made for the commercial world. I was disappointed that my bare chest wouldn’t be gracing the sides of double decker buses in Central London, but I couldn’t deny my excitement over the thought of my friends seeing me on American television. Why come to England to be discovered, when stardom was waiting at home? So I headed straight back to Seattle.

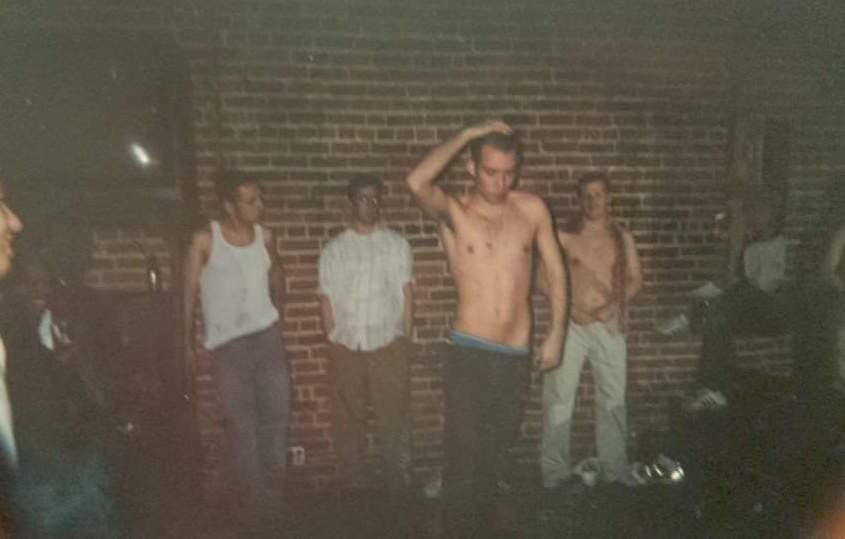

As a newly minted legal drinker, I quickly became one of Seattle’s most promising young stars in the early 2000s bar scene. While this mostly meant I wouldn’t pay for drinks if I was shirtless, I saw my newfound (and self-professed) prominence as the perfect opportunity to build my brand.

R Place was a cheesy gay bar near downtown with loud hip-hop nights, dollar beers, and a huge crowd. They also hosted the city’s premier amateur strip contest for men. As I wrote my name down, presuming that I’d win, I imagined the interviews I’d give explaining my dark past as a broke college student forced to enter strip contests just to make rent. “Those were hard times,” I’d say. “But I really feel I gained a special perspective on the objectification that female celebrities feel every day.” The industry would quickly endorse me as one of Hollywood’s leading male feminists.

“James, you’re up!” yelled Tito, the host, over booming speakers. Missy Elliot’s “Hot Boyz” began to thump on the speakers, and I could hear the crowd roar as I turned my back to them while pulling off my shirt. I realized what a wise choice I had made by purchasing a fashionable pair of Adidas wrestling boots in London, since they were now all I was wearing aside from my underpants. And I used them to climb to the top of a slippery brass pole.

“Get down James — that’s against the rules!” Tito rapped over Missy. But it was too late — I was swinging around that pole like Pam Anderson in Barb Wire, and the crowd was firmly on my side. I won the contest and $250, feeling infinitely rich. Any money in addition to the Sallie Mae loan I was living off of was another smart investment in my future — and now I could afford drinks after acting class.

But I was still intent on landing a modeling contract — so it was time to take my body seriously. With its cheap fluorescent lights, tacky gray curtains and masked nail technicians who only spoke Vietnamese, American Girls Nail Salon was the perfect place to spend my prize money on a secret chest waxing. Though I knew spending thirty-five dollars on a chest wax was a shrewd and necessary career decision, I was terrified that my worst childhood nightmare would come true: being skinned alive by Mileena from Mortal Kombat.

Skrrrrrrrrttttch — I looked down at the barren, purple wasteland that was formerly my chest. As the fluorescent lights flickered from the ceiling, small droplets of blood began to rise like pools of acid around my belly button, while random patches of hair still clung to their afterlife. Mileena began to carefully pluck the remaining hairs on my stomach with a tweezer, and I felt the buzz of my Nokia cell phone. It was a text from Jeffrey Lee, a well-connected friend and local fashion stylist.

“Great news James! I think I finally have a show for you!”

Zebraclub was an urban clothing boutique carrying hot brands like G Star Raw and Diesel, and had several locations in Seattle and Vancouver, British Columbia. Jeffrey informed me I would walk the show for their 2004 fall collection at Neighbours, a popular gay nightclub in Seattle. Only I’d be paid in clothing and gift certificates that totaled just under $200 — the professional equivalent of receiving a Starbucks gift card for Christmas.

Still in need of real money, I decided to make a quick buck before my catwalk debut. After several rounds of Long Island Iced Tea at R place, I entered the strip contest knowing I’d need to turn in a spectacular performance. I decided to show off my athletic prowess by jumping to the adjacent stage featuring the stripper pole, but in mid-air, I was reminded that my pants were still around my ankles.

“OOOOOOH!” the crowd roared. I was lying face down in front of several hundred people. “That bitch went dooooown!” exclaimed a twink in the front row. Tito announced my third-place finish and a $50 prize, and I knew I had deeply damaged my brand.

A week later at Zebraclub, Jeffrey and I gathered pieces together at a model fitting for the coming Nieghbours fashion show. I could barely walk from a severe bone bruise to my leg, and my stomach and chest were covered with ingrown hairs. Since I couldn’t fit my leg into slim black jeans and needed to incorporate my limp, I told Jeffrey that we’d go with a “slick hip-hop look.” I put on wide-legged Diesel jeans, covered my chest with a white Penguin vest and wore a backwards, plastic green visor. I would make my catwalk debut dressed as a gay Kevin Federline.

As I drove home from my first fitting as a real model, I couldn’t help but feel like my path to stardom was laid out in front of me and my 1988 Toyota Tercel. My muffler had fallen off earlier in the middle of a downtown Seattle intersection, but I was too excited by my burgeoning career to be bothered. As my car grumbled up Pike Street, I saw the muffler still sitting in the middle of the next intersection. It was rush hour, and amidst honking horns, I stopped my car and opened the door. I knew I was having a moment.

It was heavy and covered in black tar, but I’d show them how to pick up that muffler. I grabbed the steel tail pipe with one hand and the exhaust in the other; my triceps gleaming with sweat under the intent stare of halted traffic. I didn’t yet know what my future would bring, but I did know I was standing in front of a sea of flashing lights. I stood staring down the cars before me, daring them to run me over. With sixty pounds of tarred metal held perfectly upright from my crotch, I turned ever so slightly — and proudly gave them my left side.

Los Angeles Master Chorale, "our common fate" (from David Lang's 'the national anthems')

If you were lucky you spent this weekend completely ignoring everything going on in the world — and especially anything going on on the Internet — and instead lolled about in the warm embrace of joy which blissful ignorance drapes over the shoulders of everyone smart enough to turn down the noise when the opportunity presents itself. Anyway, I hope that happened for you, because today is going to be a nightmare where the best thing you might come across is a series of going-through-the-motion takes on Kanye’s new video. And it’s not going to get any better as the week wears on, either. Sorry. Say, I am not sure how you feel about choral music, but this selection from the Los Angeles Master Chorale’s recording of David Lang’s the national anthems is pretty and soothing and might be the last bit of beauty you get before you head out into the Internet and all its poison, so maybe take a few minutes and enjoy.

New York City, June 23, 2016

★★ The pre-K students, now ceremonially post-pre-K, ditched their cardboard motorboards and went chasing a basketball across the hardtop schoolyard under a darkening sky. Inside the toe that might or might not, however long ago, have been broken, an ache was lurking. The air was velvety with humidity, and the clouds held in a shapeless ambient hum. The darkness modulated up and down through the day, even allowing some shadows to form before thickening again to a rainlike dimness. Walking out into it disclosed unexpected lightness in the sky uptown. Downtown was still gloomy, though, and Brooklyn was worse: the air fetid, cigarette smoke sticking to it. An itch on the arm, scratched against a pants leg, left a smear of gnat or mosquito across the light gray fabric. Some sun found its way back through the clouds and under the expressway.

Spiders in the Highest Attics Love to Play at Acrobatics

Watching Britain leave the EU from Edinburgh

When I was a child, my father wrote a series of spider poems. One of them, Spiders in the Highest Attics Love to Play at Acrobatics, was written to the tune of Beethoven’s “Ode to Joy.” I’ve been hearing “Ode to Joy” a lot lately—it’s the anthem to the European Union. A rousing orchestral piece with just a note of threat, but mainly joy, it’s been played half jokingly, half seriously several times since the referendum for Britain to leave the EU was announced, and every time all I can hear is Spiders.

Scotland held a Vote on independence from the UK in 2014. Maybe it’s nostalgia, but that one seemed more innocent, less laced with malice. Sure, there was anger and emotion, but it was nothing like the rhetoric around the EU Referendum, which got louder and nastier, like a clockwork handle on the side of a toy.

Last month, Nigel Farage, the leader of The UK Independence Party, who has a smile like a ventriloquist’s dummy, accused Labour’s Peter Mandleson of “rubbing our faces in diversity.” Next to Nigel was Dreda Say Mitchell, a left-wing black Brexit supporter, who was horrified at what she heard. Last week, a cartoon poll by Will Dawbarn went viral. It shows five options; Remain, Leave, Don’t Know, Confused and Utterly Appalled by the Whole Thing. Utterly Appalled was winning and the cartoon struck a chord, but nothing utterly appalling had happened yet.

In the south of France, where I was visiting my parents, it was pre-thunderous. My father worried that the coming storm would knock off the England vs. Wales football match, as our cable is somewhat whimsical and sensitive. My mother and I headed to the lake to give the dog a run before the sky caved in.

By the time we got home, the football was over and Sky News was on. A young idealistic MP called Jo Cox had been shot and stabbed outside her local library, and died shortly after. She was the mother of two small children and lived on a houseboat on the Thames. She had spoken about getting a boat along to Westminster. “What a commute,” she laughed, as spray flew up and skimmed her face.

In 2013, Tory Prime Minister David Cameron promised the UK a Referendum on EU Membership as one of his election pledges. The Tory Party were losing votes to UK Independence Party, and Cameron wanted to win them back. In 2015 he did so, returning for a second term, this time not with a coalition, but with a majority. The Conservatives — a party of tax cuts for the wealthy and public service cuts for everyone else — were free to govern, but there was a catch. There would be a vote.

David Cameron struck a Rumpelstiltskin deal to win power. I guess he thought it would be OK. We wouldn’t leave. We couldn’t! Not really. Not when it came to it. The date was set for June 23rd. The EU was created after the Second World War to make sure that we looked after each other; that we were kinder, better; so that we didn’t kill each other in massive numbers. We would offer one another haven, keep one another safe, and together we would be kind to the rest of the world.

Spiders in the highest attics love to play at acrobatics.

Boris Johnson is the self-appointed leader of the Leave campaign. A Tory with a mop of toddler-blonde hair, he has cultivated an image as lovable and bumbling. As Mayor of London he got stuck on a zip wire during the Olympic Games. His voice is light, plummy and pleasant, and many people feel he is not to be trusted. In some of the debates, and he repeats the same points again and again like a broken tape. He joined the campaign believing that a Leave vote would make him heir apparent to the Tory throne.

Also on team leave are Nigel Farage of UKIP, and Tories Ian Duncan Smith and Michael Gove. IDS, as Smith is known, headed the department for work and pensions. He gained a reputation for slashing benefits, but resigned dramatically in March over disability benefit cuts. IDS has a wonderfully innocent look and a face as round and smooth as a toy man with little puffs of silver hair on either side, but it’s hard not to wonder what he’s really up to. Gove is a Tory and former education secretary, who Cameron claimed has “lost it.”

On the other side is David Cameron, the Tory Prime Minister, and Jeremy Corbyn, the Labour leader and his reluctant ally. Corbyn, a leftist outsider, was voted in as Labour leader last year in a show of massive public support. He is proudly scruffy, would like to ban trident and has a lot of lovely left-wing ideas, but he has been deliberately lukewarm about the whole Europe thing. Every time the High Sparrow appears on “Game of Thrones,” my boyfriend David shouts, “Look, it’s Jeremy Corbyn!”

In the UK, the press is not allowed to mention an election on the day of the vote. This normally leads to reporters standing outside polling stations and talking about the weather, or pretty birds. In lieu of real news, hashtags reign supreme. #Dogsinpollingstations took off once again, with tweets of dogs looking sad, bored or interested as their owners went in to vote. #Usepens also trended, because of conspiracy theories about pencils in polling stations. ‘Having trouble keeping all your livestock in one place? #usepens!’ — read one Tweet. A ninety-three-year-old mum (#93yrmum) also went viral, but I craved real news.

I spent referendum day in my flat in The West end of Edinburgh cooking two curries, one vegan, one not. I pottered round the kitchen, cooking, cleaning and going slowly insane. At 8 p.m., it was time to go across town to meet David so we could carry a TV set across town, from his parents’ house to mine, so we could watch the result. On the way, I met a woman who asked me for directions to the local church, which was her polling station. I walked with her.

“What did you vote?” she asked me.

“I voted Remain,” I said.

“I think it’s kinder that way,” she said.

Later, as David and I lugged the flatscreen across the meadows which fill central Edinburgh, I said, “We are so Remaining. There’s no contest.”

“Tap wood,” he said, “touch a tree.”

But I was carrying half a TV and couldn’t tap wood without dropping it.

My Swedish friend Johanna told me she took the vote very personally. “I mean it’s people like me who it’s aimed at. Everyone says, oh no, it’s not you. But I am an EU Migrant, I have come over here and I’m doing minimum-wage jobs, I’m literally one of those people who they talk about, coming over here and stealing jobs.” We sat close on the sofa and opened some beers. David put on The Final Countdown by Europe. We would know nothing until 10pm, but the hour was so tantalizingly close. More of our friends arrived. We had all voted remain, with one exception: my friend Daniel who believed that Britain was holding the EU back from being the super-state it could be.

We put on the BBC at three minutes to, and watched as David Dimbleby, the anchor did a little shiver of anticipation. We all know Dimbleby from previous elections — we’ve watched him present since we were young kids. At one minute past ten, Nigel Farage said he thought Remain had won, but there would be a next time. There were gleeful cries. Sure, the new polls were neck and neck, but so what — it looked like it was all over.

I started dishing out food. Gibraltar was first to declare. “Good Evening Gibraltar!” we yelled, and it was as expected, Remain by 19,322 votes to 838. Then there was Newcastle, a safe Remain which came in with nowhere near the 60/40 margin expected. “Not good,” said David as he refreshed Twitter. Next to announce was Sunderland, expected to Leave. Leave it did. My friend Daniel was at home moderating comments for the magazine he writes for. “That’s not good for leave! I mean remain. Brain frazzled,” he messaged me, but our TV was one minute behind and I didn’t know what he meant. Sunderland came in at 61 to 39 a few seconds later. Everyone watched intently, but Daniel’s words stayed in my head, and I knew what to expect.

The EU anthem came onto David’s playlist on his laptop. Spiders in The Highest Attics Love to Play at Acrobatics, but I couldn’t remember the rest of the words, so I just thought sp-sp-sp-spiders sp-sp-sp-spiders sp-sp-sp-spiders sp-sp-sp frantically to the tune, though I knew that wasn’t right at all. In a corner of the living room, my friends Sara and Atilla were talking about getting married. It was not a romantic proposal, they have been together for years and always assumed they’d get married sooner or later. Atilla is from Hungary, and Sara is British. It was suddenly looking like they’d be getting married sooner. Tai, who also has parents in France, went through to the kitchen and plucked at his mandolin. He was trying to play Spiders.

In The Guardian, Polly Toynbee called for an end to this midsummer madness, and I came up with the best Facebook status. I was going to post, “If we shadows have offended,” from A Midsummer Night’s Dream, once it was all over. Only now it looked like I wouldn’t. The room was feverishly hot with summer and bodies and the night was almost light. My flatmate Vicky had put cans of beer in the freezer and got them out, giving one to each of us to cuddle, the opposite of a hot water bottle.

What time did we know? What time did people start leaving? I was taking notes. David had barricaded himself in the bedroom, and when I dragged him out to be sociable he sat cross legged on the floor softly swearing at his laptop. Linsday Lohan or someone using her account was livetweeting so aggressively that some speculated she was hacked (all the relevant tweets have been deleted). ‘You can’t sit with us, tweeted MP Stewart McDonald. We said goodbye to people until it was only Vicky, Johanna, David and me. The temperature dropped as people left — then it was half three, and we almost knew, but not quite.

Cameron handed in his resignation at 8 a.m.; I rather dread who we’ll have next. There are also calls for the High Sparrow to go, but whether he will or not is a different matter. Some compared Brexit to a Trump presidential victory just as Trump touched down in Scotland. He was on his way to his Ayrshire hotel and golf course, the Trump Turnberry. Some locals displayed Mexican flags in protest. First Minister of Scotland Nicola Sturgeon demanded another Referendum on Scottish Independence, sterling plummeted and reports came in that Morgan Stanley would clear out of London, though these have been refuted by the firm.

Twitter exploded with end-of-the-world memes, and people in my Facebook feed were devastated. Nigel Farage was delighted, and I wondered what Europe made of it all. I threw up when it was all finalized around 6 a.m., or maybe earlier. I had lost track of time. I chatted with Sara who said maybe she won’t need to get married after all as Atilla has been here long enough for it to be OK. I’m not sure how long that is. The idea of people getting deported terrifies me. I’m saddened the possibilities severed, the loss of freedom to move seamlessly through a continent, living and working in cosmopolitan cities.

When I opened my inbox that morning I saw an email from my Dad. The subject line simply reads “Acrobatics.”

Spiders in the highest attics

love to play at acrobatics

swinging through the dusty air

with speed so swift and grace so rare

along fine tightropes swift they tread

and even do in on their head

and if they slip they aren’t upset

for they have spun a safety net

Except Britain just voted to lose the safety net — we’re no longer arachnids, just common insects.

Hope Whitmore is a young-ish writer who lives in Scotland. She likes stories, as her dad read to her when she was a child, and she looks for the narrative in everything. She also likes running, swimming, cooking and eating. She’s a romantic, and shares a flat with another writer who is also a romantic — Vicky Hood. They share many pretty dresses.

Jherek Bischoff, "Closer To Closure"

It is generally best not to describe inspirations.

The press materials for Jherek Bischoff’s forthcoming Cistern say it is “inspired by time Bischoff spent improvising in an empty, two-million-gallon, underground water tank, with a 45-second reverb decay. The unique acoustics of the space forced Bischoff to slow down and adapt his compositional approach — something which, unexpectedly, brought him back to his childhood, and the slow-pace of life he experienced growing up on a sailboat,” which [OH MY GOD “JERKING OFF” MOTION SO HARD MY HAND IS GONNA BREAK AWAY FROM MY ARM AND FLY UP TO THE FUCKING MOON]. But I have heard it all and it is one of my favorite things this year, so it is yet another lesson (as if one were needed) about how words are poison and the fewer of them used the better. In fact, I’m sorry I even brought it up. You should listen and enjoy and make sure to pick up the album.

New York City, June 22, 2016

★★★★ The sun was already hot on the preschool playground as the children trooped through. A man got off the elevator with his white shirt soaked through in the middle of the back. Dust or pollen floated in the sunbeams, and the parked cars were dusty or blotchy in the unsparing light. The brightness shone through the cracks in the lining of the banner outside the library, the red veiny pattern disclosing the fact that the lining existed at all. The wind gusted, to little or no effect on the temperature. Clouds passed quickly above the forecourt plaza, down in which the sun and wind alike could not quite reach. Within those limits, at that moment, there was nothing that could have been improved on. The four-year-old declared he was too hot and demanded to go upstairs.

History Lesson: Channel Surfing

You won’t believe what people used to do before their interactions with the outside world were confined to their fucking phones.

“For most of us who grew up in a time when people still sat in front of the TV and just flicked through the channels to see what was on, C-SPAN was the group of channels you frantically clicked right through.”

— I did not wake up this morning with any greater desire for death than is usually the case, but seeing this description of C-SPAN in a piece advocating for the importance of the network, you can only imagine how desperate I am now for the final embrace from existence. I am indeed a person who grew up when people still sat in front of the TV and just flicked through the channels to see what was on. Guess what? THERE WERE THREE OF THEM THEN. I have no place in this future world of yours.

A Pilgrim's Progress

How realistic is ‘Sweetbitter’ about the hospitality industry?

Last year, hospitality mogul Danny Meyer opened a new restaurant in the recently relocated Whitney Museum in New York’s Meatpacking District. The New York Times food critic Pete Wells opened his review of Untitled with some context for Meyer’s burgeoning armada of expensive, middlebrow eateries. Wells said the group comprises “polite restaurants where polite people are in very little danger of being challenged or provoked. Although Mr. Meyer has worked to make his name synonymous with hospitality, what his restaurants sell above all is reassurance.”

I’m no fan of Wells, but I had to admit, there’s something shrewd in this comparison. Whether it’s fine art or fine dining, the fundamental imperative of middlebrow culture is the same: give the people what they want. If the key to satisfying popular demand is to offer the expected, however, the trick is to not to get caught being boring.

Meyer has made a killing in the restaurant industry by striking just this balance. Stephanie Danler — whose recent novel, Sweetbitter, is based on her time working at Meyer’s well-known Union Square Cafe — has carried over the secret of her former boss’s success into the realm of literature. Sweetbitter promises an authentic view into the world of New York City restaurants, but, with few exceptions, the vision that emerges stays safely indebted to the most conventional understandings of what that world is like. As a result, readers experience a sort of double pleasure. They’re invited to feel like they’re getting something new, and at the same time, remain satisfied in the belief that their assumptions have been right all along.

From the outset, Sweetbitter reads like a kind of contemporary Pilgrim’s Progress: a young naïf makes her way in a world peopled by animate clichés. Tess, the novel’s protagonist, names a mass of them allegorically: “Debutante-Smile, Guy-with-Clark-Kent-Glasses, Guy-with-Long-Hair-and-Bun, Overweight-Gray-Hair-Guy…Mean-Girl, and Russian-Pouty-Lips.” These characters tend not so much to speak as to espouse, spouting the truth of themselves in a language that is almost compulsive, automatic, as when a barista muses, “the Marzocco, it’s the Cadillac of espresso machines.”

The scenes in the novel that take place outside of the restaurant are far more convincing. Danler’s characters are capable of language unencumbered by industry stereotypes only when they’re off the clock, and this feels true to life. After all, Danler’s particular background is in a corporate restaurant group that has taken pains to develop an ample and idiosyncratic language to describe the ways it does business. Meyer’s employees are taught to make “charitable assumptions,” to “take care” of customers (“guests”), and to deliver “hospitality” rather than service. They’re told that 49% of their job is executing technical skills, while the other 51% involves performing intense emotional labor. All of this language infiltrates the novel in a raw, unmediated jumble.

As a fellow Union Square alum (Danler and I did not work there at the same time) I know that it can be challenging to find alternative ways to communicate what goes on there. The discourse is constitutive of the experience, if you want to get all lit crit about it; it’s hard to divide the one from the other. Overall, Sweetbitter suffers from an inability to disentangle reflection from corporate cliché. The result is a sort of confused free-indirect discourse, a hybrid narration that struggles to clearly extricate itself from Meyer’s real-world sloganeering. When Tess remarks, for instance, on the senior servers’ ability to remember the whims and preferences of the restaurant’s regular guests, she says:

whatever computerized tracking system they used — and I’m sure it’s top of the line — it couldn’t stand up to the senior servers and their memories. Their innate hospitality. Their anticipation of others’ needs. That was when service went from an illusion to a true expression of compassion. People came back to the restaurant just to have that feeling of being taken care of.

She begins with a newcomer’s amazement at a world she’s only begun to inhabit, and ends in a more or less direct paraphrase from the Union Square employee handbook.

The novel does make a valuable contribution: it tells Tess’s story without recourse to the traditional narrative of a young, aspirational waitress in search of something else. Tess isn’t looking for a way out of restaurant culture; she seeks instead to make sense of it, to embed herself in its pleasures and turmoil. Danler has been clear about this intention. She said in an interview with Vogue, “I didn’t want to write about restaurants in the way they had been written about before as a job, a place to pass time and make money and leave off the résumé…It can feel like a very full life.”

Sweetbitter is full of period details about New York at the beginning of the twenty-first century. Williamsburg gentrifies; 9/11 happens; an iPod makes an appearance alongside a mix CD. But the novel also marks a real historical shift within the restaurant industry. For the better part of the twentieth century, restaurant work had a reputation for being unpleasant and undignified, but that has changed significantly in the past two decades. A “career” in restaurants, especially at the high end of the spectrum, has become an increasingly desirable vocation, and the industry has exploded accordingly. As a smart, ambitious protagonist entrenched in restaurant culture, Tess is a very specific historical character. It would be hard to imagine a figure like her in literature, even a few years ago.

Paula Rester, wine director for La Corsha Hospitality Group in Austin, Texas, recently reflected on her own experience with this cultural shift. She wrote in an email, “I definitely faced a stigma within my own family when I was ‘coming up’ in the restaurant industry. I came from a middle-class background, was smart, educated, and my mother would often tell me her greatest fear was I would become a ‘forty-year-old waitress’ often wondering aloud where she had gone wrong.” (She added that her mother has since become her biggest fan and derives great pride in her career arc.)

Rester attributes her particular career energy to a decision to cultivate an expansive knowledge of wine. In Sweetbitter, Tess’s own such education, under the aegis of a senior server driven by an epicurean urge to link sensory pleasure to philosophical insight, is slow, impassioned, gauzily erotic. At times, she imbues her speech with rich lyrical flourishes; at others she sounds like she’s quoting from a cookbook. “The chalk content in the soil,” she announces to a group of fellow servers, “the cold northern climate, the slow second fermentation…You taste it…and you know it’s Champagne.”

These experiences are central to Tess’s immersion into the restaurant world, but they are also part of a broader process of development from gawky amateur to fully-formed modern urban subject. Her inroad might be food and bev, but this is just one of the many forms of cultural capital Tess acquires. “I could talk about Billy Wilder and Djuna Barnes and the new bone-marrow dish at the gastopub in the West Village,” she says.

Throughout the novel, Danler is remarkably attuned to the complex class politics of this form of development. Of the restaurant’s more experienced servers, Tess says, “they were so well versed in that upper middle-class culture — no, in the tastes of upper middle-class culture — they could all pass. Even most of the cooks had gotten an Ivy League education at Cornell before they spent a fortune at CIA. They were fluent in rich people.” This is the novel’s most profound contribution, and the insight that links Sweetbitter most thoroughly to the contemporary restaurant scene. Those looking to find their footing are compelled to, as Danler puts it, “pass” as wealthier than they are. The easiest way to do this is, of course, by buying stuff.

It’s worth noting that Thorstein Veblen (sorry!), best known for coining the term “conspicuous consumption,” also came up with an analogous concept, “pecuniary emulation,” which he used to describe the economic behavior of poorer people who mimic the rich by purchasing the same commodities. The restaurant world is a perfect place to see this in action: craft cocktails, quality wine, and adventurous dishes may be priced with affluent consumers in mind, but they are sought after and consumed just as readily by restaurant workers themselves.

In a review of Sweetbitter for the New York Times, chef and writer Gabrielle Hamilton gestures toward this phenomenon, when she notes, “busboys these days have more in common with the class they serve than ever before.” In a certain limited sense, Hamilton is right. From the point of view of consumption, these two groups increasingly share a good deal. What she seems not to acknowledge is that this similarity doesn’t actually do away with the significant class divide that persists between them.

The industry is at a critical impasse. It may be newly possible and freshly desirable for young, smart professionals like Rester to make a career in the restaurant world, but the specific avenues for this type of development remain largely undefined. As a result, they dine out extensively. This isn’t merely internalized pressure to be up on industry trends. Friends and former colleagues have all experienced pressure from managers and more seasoned veterans to spend their off-hours in other restaurants.

A friend put it well when she looked back on her own time as a bartender at Union Square Cafe: “I remember having to study the weekly Times restaurant review and being [quizzed] on it… We were explicitly told to go out and dine at these expensive-as-fuck restaurants. I think it’s a little tacky to put pressure on blue collar workers to spend a high percentage of their paycheck for one meal.”

Her call to class here is as resonant as Danler’s. A few people I spoke to acknowledged the enormous financial outlay that goes along with developing a professional standing in the restaurant world, but justified it, likening it to an apprenticeship phase where the initial buy-in is high, but the eventual rewards stand to compensate. This makes a certain amount of sense, and the restaurant industry isn’t alone in this expectation. But the analogy to a guild system breaks down when you consider the material contexts in which these practices of consumption unfold. There’s no real guarantee that the investment will pay off, and very little sense of the specific ways in which sophisticated purchasing on the part of service laborers will help them advance their careers.

Aspiring restaurant professionals don’t comprise an assembly of journeymen; they’re part of a working class. And so despite an evolving potential for career development, they are still by and large exposed to significant risk. As Danler’s novel testifies, pretending otherwise can be a lot of fun; there is a thrill to this ritualized passing. But mimicking the tastes of the upper classes doesn’t do anything to guarantee restaurant laborers the relative security those classes enjoy. After nearly a decade in the restaurant industry, my former colleague Kyle decided to switch careers, largely because this illusion had begun to evaporate. “It was so uncomfortable for me,” he said, “that’s a big reason that I haven’t stayed in the industry…It felt really gross.”

Patrick Abatiell has written about restaurant labor for The Awl and for Public Books, where he is a contributing editor. He works in a restaurant.

Substitute Teacher

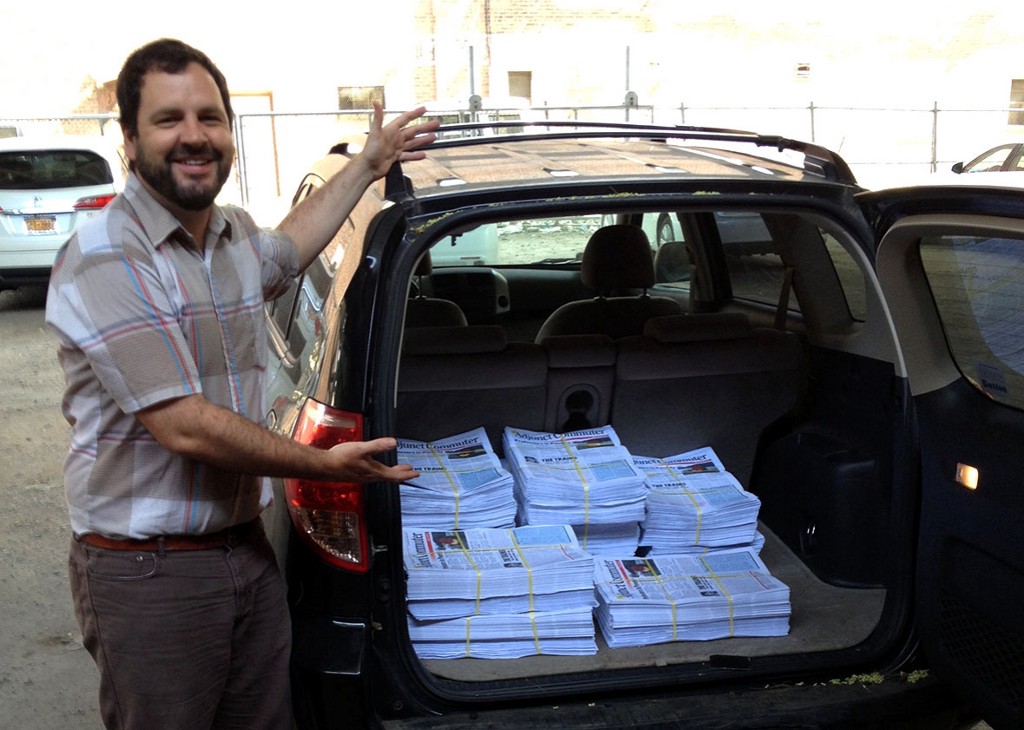

Recalibrating the adjunct with Dushko Petrovich

Now that everybody knows how rubbish it is to be an adjunct, what happens next to the “professor” as a cultural figure? The cartoon academic is old, white, male, has elbow patches, and is rich. That doesn’t fit the reality of most professors these days, especially the rich part: more than half of college faculty is now part time.

The artist, teacher, writer, and editor Dushko Petrovich is recalibrating our understanding of the adjunct professor into something closer to art. Petrovich is probably best known for co-founding and editing the art magazine Paper Monument, as well as his artistic practice, which he describes as “a mix of painting, writing, editing, and really anything else that becomes necessary.” (Disclosure: I work at Paper Monument’s sister magazine n+1). He has also had a varied career as a college teacher — last year alone, he taught at Boston University, RISD, Yale, and NYU. He has perma-ruffled hair and a nice, ursine aspect.

In 2015, Petrovich launched a multimedia project called Adjunct Commuter Weekly. You can read about it in The New Yorker, Slate, and the Wall Street Journal, if you like. It only came out in one edition, then “rebranded” as a “multimedia platform” due to the “financial and time constraints of the adjunct commuting staff.” It is entirely about the challenges faced by adjunct faculty. One notable piece was Kristen Dombek’s, “Five Trains Each Way Means Ten Trains A Day,” which was about taking a lot of trains. Every staffer is an adjunct, which means that Petrovich will have to resign: he just got a tenure-track job as Assistant Professor at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago.

ACW is a satiric comic performance, one borne of pain. It contains real and lucid commentary on employment conditions, but is also ruefully funny. Petrovich describes the project as the “only sane response” to an “insane work situation.” Driving “from Boston to Brooklyn or from Providence to New Haven on late nights,” Petrovich felt alone. ACW was founded to bring people together, and to spread its tote bags across campuses, in turn spreading awareness. I have proudly hauled mine from campus to campus, clutching it on my lap (when I could get a subway seat) like some kind of talisman that would protect me from my lack of health insurance with its humor. ACW has recipes, advice, and “Adjunct Sudoku” (you can’t use numbers higher than 3).

Petrovich is also currently working on “a ride sharing app, called Unter, so people can coordinate their transportation and be in touch with other adjuncts.” It’s quite difficult to tell whether he’s being serious or not, but the answer is probably: art.

Petrovich was born in 1975 in Quito, Ecuador, and went to a couple of schools there before his parents split up. Then he, his mother, and his brother went to Ohio (first Perrysburg, then Bexley). From there, he went to Yale, where he majored in art. He studied etching in Florence for a bit, and got an M.F.A. in painting from Boston University. Petrovich spent a year at Royal Academy in London, where he was the “Starr Scholar, an embarrassingly titled position they gave to one American Artist-in-Residence each year.”

There’s something about ACW that feels very generous, very teacherly to me. I asked Petrovich whether he liked any of his teachers growing up. In elementary school, he said, the kids had to vote for their favorite class. The girls voted music, the boys voted gym, and Dushko voted art. He had a stylish middle school art teacher named Paula Len, then a laconic chainsmoker named Peter Cooper — Coops, for short. Art Club met on Monday nights from six to nine.

These are the details that a person remembers when learning and reading and making work has got deep down into their soul at a young age. Usually teachers have some kind of memory like this, and Petrovich has always liked teaching. He started out at B.U. in the painting department. He likes to talk to other artists, to hear what young artists are doing.

I wondered, talking to Petrovich, what the relationship between his editorial and teacherly roles might be. He co-founded Paper Monument with fellow artist Roger White in 2007. White and Petrovich noticed that “there was a lot that was being left out between the academic art journals (October, Grey Room, etc) and the commercial art magazines (Artforum, Frieze, etc),” so they dreamed up a magazine that would instead focus on readers and writers, foremost.

A key goal of Paper Monument has been to elevate to the level of print issues that people around White and Petrovich were discussing: art world etiquette, art school assignments, and so on. The title Paper Monument, of course, telegraphed their “reluctance to keep up with the pace of digital publishing.” By Petrovich’s own admission, Paper Monument publishes “very periodically.” I liked that Petrovich admitted that Paper Monument now functions like a “kind of instant credential”: people know he made that magazine, and that it worked out.

Petrovich’s new job at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago is in a graduate program called New Arts Journalism, and it will be a longterm home for the itinerant Petrovich. And his wife, Magdalena Moskalewicz, will be teaching in the Art History Department at SAIC. I often can’t help but resent people who get tenure-track jobs — it just sneaks up on me, although I feel a little bad about it. But I’m happy for Petrovich, because he has helped and taught and edited many people, and Adjunct Commuter Weekly became a project that I could cling to in a time when I needed it quite badly. Projects like that one become solidarity touchstones, and I’m grateful for it.

My ACW tote bag is almost worn completely through. I’ve poked holes in it with errant pencils, and torn one of the straps. But I’ll keep lugging it across town, heaving on and off my shoulder on the L train until the thing falls apart completely: that’s what adjunct commuters do.

Josephine Livingstone is a writer and academic in New York.

A Poem by Joanna Fuhrman

Mauve Decade

Much has been made of our father’s missing

memories. The captain discovered them,

book fishing with his sister on a ship

made from black gills and rusted bones.

Memories? The captain discovered them

with his crush on a river of lost ships

made from black gills and rusted bones;

they were hoping for more than a touch.

With his crush on a river of lost ships

all was possible, bursting with smells.

They were hoping for more than a touch,

received less than a punched kiss.

All was possible. Bursting with smells

of the shore. He had planned for love

received less than a punched kiss,

no more than a smudge in the margins

of the shore. He had planned for love

to power the turbine blades, but

no more than a smudge in the margins

would propel the journey backwards.

To power the turbine blades, but

how? Who was he now? What scent

would propel the journey backwards,

into the cave of our father’s lost youth?

How? Who was he now? What scent

did he touch in the creases of her blouse?

Into the cave of our father’s lost youth,

a fever that bled into stars.

Did he touch, in the creases of her blouse,

his own skin curled in the shape of a rose,

a fever that bled into palpating stars,

book fishing with his sister on a ship?

for Guy Maddin

Joanna Fuhrman is the author of five books of poetry, most recently The Year of Yellow Butterflies (Hanging Loose Press, 2015) and Pageant (Alice James Books, 2009).

The Poetry Section is edited by Mark Bibbins.