Alien Panda Jury, "Missing Panda"

That part of your life is over now.

And that was your summer. I hope it worked out for you. Don’t worry, it will still be hot and sticky well into next month, and possibly even November, but it will get darker earlier and everyone around you will have their Very Serious Person face on, making you wonder what’s wrong with you and why you aren’t able to make yourself seem as serious as they appear to be about things that are so meaningless. Gradually you will forget summer ever happened and any possible joy you were able to draw from the sunshine will fade away, leaving you empty and broken and counting down the days until another fucking year of your life is over and a new one begins. But we’ll have plenty of time to discuss that over the next few months. Until then listen to this, and take full advantage of today, which is the last time for a while that people will be relatively quiet and leave you alone as they “get out from under” and “catch up on emails” and all the other things they say to signal how important they are. Enjoy.

New York City, September 1, 2016

★ The morning was gray and wet, sometimes getting wetter. Water beaded on the steel bowl that the hard boiled eggs had been cooled in, even after the ice water had been dumped out. The clouds thinned deceptively and then a new downpour came by midafternoon. It was only a little too hot for the rain jacket, hot enough to leave the front open and let the shirt get damp. The rain stayed for a while then stopped, and the light improved for a while before getting ugly again. Stirring phenomena seemed to be developing in the western distance but down in the streets all was yellowish and upsetting. Brightly painted toenails were still out in the damp and the gloom, but some other signal had reached the man in the bus shelter, in jeans and a thick sweater, and the bagpiper nearby in his tweedy cap and pants with the luster of corduroy. The walk home was a race to get up out of the shadows before the light bloomed, as it certainly would, and did: A pink plume stood up against churning darker clouds, and near scarlet light flared from a vent pipe.

You Will Know Them By Their Whoops

Why do we want to be surprised by “The Millennial Whoop” in pop music?

Two weeks ago, a musician named Patrick Metzger wrote a slick-looking blog post about a trend he’s observed in recent pop songs that he says has “plagued the airwaves for the past several years.” He nicknamed it “The Millennial Whoop”—the toggle between the fifth and the third pitch on a diatonic scale. Even though it’s obviously been around forever, as long as there’s been music and probably long before then too, it is definitely having “a moment.”

But the real pickup came a week later, when Quartz turned it into an insanely sharable video with all the examples compiled next to each other and next thing you know we’re back to “decoding millennials” as though they’re sending each other subliminal messages.

“The Millennial Whoop”: The same annoying whooping sound is showing up in every popular song

First of all: no. This is not a millennial thing. It’s a laziness thing. All the songs sound the same because they ARE the same. It’s also an echo chamber: many of them are written by the same few producers. As Metzger writes, “It’s the kind of musical phrase that we seem to know instinctively.” Yes, yes. Almost like baby talk or birdsong. So if we all know it, then what does it have to do with millennials? Most of them aren’t producing or really even writing any of this stuff, they’re just iterating. Also, what’s more interesting here is not the notes themselves but the repetition of the same syllables, “wa-oh, wa-oh, oh, oh.” This isn’t happening in all pop songs, it’s just that pop songs have become so tautologically defined as to require a millennial whoop to sound like pop music.

But we’re determined to credit the mysterious monolith—we are captivated by a demographic that marketers basically invented because we live in a social era where the only thing that matters is an audience. The real story here is the lag time between Metzger’s post and the explosion of the story in the general population’s newsfeeds. Quartz’s Michael Tabb basically struck platinum by quilting all the whoops together into a video, sponsored by the luxury car brand Jaguar. From there, it was off to the races. Just look at some of the headlines around this whoop story:

The Millenial Woop: The Reason Current Pop Songs Are So Catchy

(Elle UK)

Isn’t it whoop not woop? Also the subhed is really reaching: “singers using secret subliminal messaging that has their songs in your head for days”

The Millennial Whoop: the melodic hook that’s taken over pop music (The Guardian)

This one actually might be accurate, but it’s still fueling the millennial fire.

Once you hear it, you can never un-hear it (Maxim)

Yes, because it’s literally everywhere, not just pop music.

The ‘Millennial Whoop’: The Musical Trope That’s Suddenly Everywhere (Mental Floss)

Not so suddenly, but everywhere, yes.

The millennial whoop: the key to modern pop (BBC)

Yep. Now we all know

THIS WEIRD MUSIC THEORY WILL BLOW YOUR DAMN MIND (Paper)

Having your mind blown by this is like having your mind blown by those “crazy card trick” websites that read your mind and tell you which card you chose because you were subtly directed to by the game’s instructions. We know it’s fixed but we want to believe.

But the whoop is not exactly a hoax or a trick, but neither is it something we should be so impressed by. The Outline’s audio director John Lagomarsino wrote in an email, “It may be true that that gesture is occurring more frequently in modern pop music, but I’d be inclined to read that as just part of the musical vernacular, like certain patterns in drum beats, or common bassline gestures. It’s just another hallmark of a style.” A pretty tired style if you ask me!

Awl pal and musicologist Brian Barone said, “There’s a long history in western thought about music of essentializing moves equating certain sounds with certain groups of people — “women’s music” goes like this; “African music” works like that. Which, uh, can be a pretty busted approach both musicologically and politically.” He also asked the most important question, “is the idea that the Millennial Whoop expresses something about millennialness? Or that something about our “generational character” draws us to it?” No. The name is just branding, like any other thing we apply it to. You know what else could we say has a millennial sound to it?

Tufted titmouse

XC33596 Tufted Titmouse (Baeolophus bicolor)

Cuckoo clock

A Gregorian chant

MillennialWhoop for the millennia. #GregorianChant. #Mode5 (alternating scale degrees 5/3/5/3)

Beethoven’s Für Elise

We’ve been harping on this pattern for a long time, and it’s never going away. It’s not really even bad or annoying, but after a while it does get repetitious. But it doesn’t have to be that way! Try a little Fiona Apple once in a while:

Yeah there are thirds and fifths in there too, because those are some of the most basic building blocks of music. Nothing wrong when a song ends in a minor key. Make note, millennials.

Manatee Commune, "What We've Got" (Ft. Flint Eastwood)

This is it.

Remember how excited you were back on Memorial Day weekend? All the things you planned to do and all the chances you were going to take and all the fun you were going to have? Well, you’ve got three days left to cram in everything you didn’t get around to before life suddenly gets serious again and we all put our heads down to focus on our very important lives and careers. Before you realize it the clocks will go back and the darkness will settle in and you’ll be taking the heavy coat out from the closet and wondering why you didn’t get it cleaned when you had the chance and making travel plans for Thanksgiving and fretting about which holiday parties you haven’t been invited to and sitting alone in your apartment watching TV because it’s just too cold to go out. That’s all in front of you, and it’s closer than you think. So enjoy the next three days, if that is even possible for someone like you. You’re not going to get them again for a whole year.

Hey, so I am a little late to this Manatee Commune tune, but it’s terrific. It sounds like summer, which, as we know, is ending. It’s the perfect track to play us off. Enjoy.

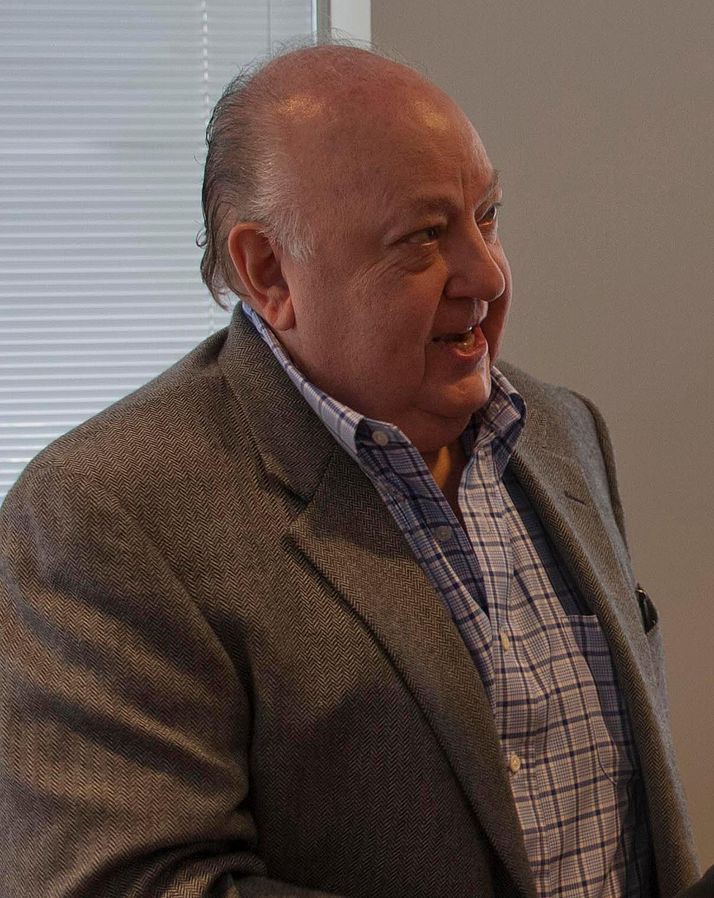

The New Roger Ailes Piece Will Make You Sick

But read it.

It is unfathomable to think, given Ailes’s reputation, given the number of women he propositioned and harassed and assaulted over decades, that senior management at Fox News was unaware of what was happening. What is more likely is that their very jobs included enabling, abetting, protecting, and covering up for their boss. “No one said no to Roger,” a Fox executive said.

It would be unfortunate if Gabriel Sherman’s latest report on Roger Ailes’ tenure at Fox News got lost over the long weekend, or in the scramble everyone goes through getting back after the holiday, so read it now or save it to whatever app you use that makes sure you don’t forget about it. Either way, be forewarned that no matter how low your expectations for the behavior described within you will still be disgusted and shamed by what you learn. That probably does not help sell the piece, but its important that you read it, so make sure you take some time to do that.

New York City, August 31, 2016

★★ Sometime in the night it became impossible to leave the windows open. By morning the humidity was dread-inspiring but harmless as long as the clouds held. People were out all along the wall of the office building in the neutral dampness, eating or smoking or smartphoning. As the sun found its way through, things quickly got unpleasant. The light mercifully faded away again, then rallied unexpectedly. A reddish pit bull sat very upright, gazing out the open rear side window of a parked luxury SUV while the stereo played.

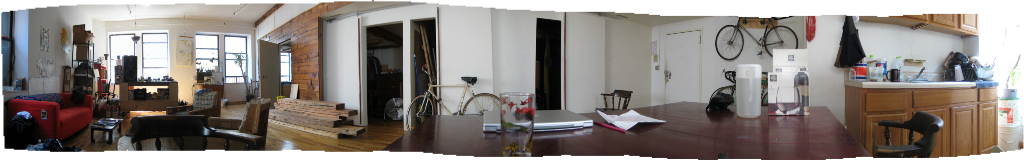

What Does It Mean To "Live Like An Artist" In New York?

On the history of loft living, and its changing definition.

When my twenty-two-year-old artist father moved into his raw loft space in SoHo in 1975, he had to pay an extra $1,000 to get basic plumbing risers installed. The floor was stained with machine grease from the bookbindery that had operated there; there were no walls or partitions, and he slept on a mattress in the corner on the floor. Trash collection was seldom, and basic groceries were a half-mile away.

For the first couple of years, a printing press still operated upstairs, shaking his entire building during business hours.“This is not an apartment!” his family cried. Yet, he never had to take a roommate to make rent. He had the entire space to himself, where he could set up his creative life: print his etchings and work on oil paintings and illustration projects. Sometimes, on breaks, he would pretend he was a baseball player, running around the 1200-square-foot space and sliding into an imaginary third base.

Even while it was still illegal, living in former factory buildings was already ascendant as a “lifestyle.” The average SoHo loft was a cavernous 2,100 square feet; taking up space was part of the radical project of loft living. In 1970, Life published a photo essay called “Living Big In a Loft,” showcasing the more grandiose pads of various early loft inhabitants, and the freedom that all that space gave them:

Multimedia Artist Bob Wiegand swings from a trapeze he installed in his 2,500 square-foot loft, on the fifth floor of a cooperatively owned building. He enjoys performing acrobatic stunts in his studio, although he admits climbing the 144 stairs from the street is probably all the exercise that anyone needs.

The law lagged somewhat behind. In 1971, the New York State Legislature added Article 7-B to its Multiple Dwelling Law, recognizing that “there is a public purpose to be served by making [these] accommodations readily available for joint living-work quarters for artists … [who] require larger amounts of space for the pursuit of their artistic endeavors and for the storage of the materials… [and] the financial remunerations … from pursuit of a career in the arts are generally small.” This Artist-in-Residence (AIR) initiative, by allowing this residential use, made it possible to legally occupy former industrial buildings by creating special AIR Certificates of Occupancy.

These legalized units immediately jumped in value, and by the 1980s, most lofts were priced out of reach of the very class of people that had transformed their use. As a 1979 New York Magazine article put it, “in a textbook example of the role of art in urban renewal, [artists] were soon followed by the people who are interested in artists (e.g., gallery owners and collectors) and eventually by the people who are interested in people who are interested in artists (e.g., New York dinner-party goers, a vast crowd).”

As the upper classes moved into SoHo, the media portrayed the need for space as supporting a bourgeois lifestyle rather than the original artists’ utilitarian purposes.. Enormous, decadent-looking lofts became a critical component of many popular films set in New York in the late twentieth century, such as Fatal Attraction, Hannah and Her Sisters, Ghost, and especially Big, where the man-child protagonist bounces on a trampoline in his loft on 85 Grand Street — a perfect setting for sidestepping the conventional requirements of growing up.

Eventually the term “loft” came to describe something more than a physical structure — starting in 1970 with David Mancuso’s invitation-only parties called “The Loft,” and migrating quickly to more remote industries. In fashion, it eventually became shorthand for “bohemian luxury,” starting with the Ann Taylor spinoff LOFT in 1995, which spawned countless aspirational imitators. In 2015, the median rent in SoHo was $3,875 according to the website Zumper. That average includes, of course, all the aspirational listings from newly built or non-loft buildings that can claim extra cachet by using the word.

In industrial Brooklyn, to which the dream of loft living has been displaced, high demand and prices have transformed the prospect of affordable living in New York. Lofts have a particular utility in this, with their open floor plans maximizing space for ingenuity and profit. In 2014, seeking an apartment share, I toured a loft on Bushwick’s Siegel Street. It had a cluster of four “bedrooms,” all of them clamoring for the loft’s single, enormous window. The cubicle-like rooms were stacked on top of each other, resulting in very low ceilings on the top two rooms, which you reached by a handmade wooden staircase. A New York Times Magazine article about a similar loft compared such rooms to horse stables.

Two of the rooms had walls that were partially open to adjacent, windowed rooms, providing some indirect light and air. We spoke about the feasibility of closing off these openings for privacy. Everything seemed to be made out of plywood. (There is more at stake in these situations than just hearing your roommates’ sex and music. A recent Buildings Department violation levied against the infamous McKibbin Street Lofts cites that new walls are made of combustible materials; this is in a building with a history of fire sprinkler problems).

At the Seigel Street loft, we four potential roommates also discussed adding a possible fifth, who would be travelling frequently and defray the cost (unless the landlord, who was proudly showing us the space, would figure this out and charge even more rent.). I am relieved, for various reasons, that this living arrangement never happened.

Many of these arrangements in today’s lofts hearken back to the Wild West or the slum tenements of the nineteenth century, with their overcrowding and constant turnover, as well as their lack of light in many rooms — ironic, considering the usually light-worshipping loft aesthetic. Jacob Riis’s famous photo-survey of New York City tenements wrote of people practically living on top of each other, without the light and air that we take for granted in modern apartment buildings today.

According to the New York State Multiple Dwelling Law, in all buildings built after 1929, “every room… shall have at least one window opening directly upon a street … Every such window shall be so located as to light properly all portions of the room.” The size of windows is also regulated; they are required to have a surface area of at least 10% of the floor area. Though the Loft Law, intended to protect joint living-work quarters for artists, eases up on certain requirements like this, the owners of most Brooklyn loft buildings have not made even preliminary steps to bring their buildings up to code. Thus, many “tree houses,” “cubbies,” and other loft-style bedrooms are dangerously illegal. There is also a 1950s law on the books, albeit rarely enforced, that renders it illegal to live with more than three unrelated roommates.

In New York, Breaking a Law on Unrelated Roommates

In late 2014, I responded to a posting from Alec Henry, a fellow alum from Wesleyan University who was advertising a room in a loft building near the Morgan Avenue L. Though I never got to see the room (someone had already snapped it up), I asked him about the space, which had seventeen rooms and three bathrooms. (Tenement-house legislation in New York from 1867 established a minimum of one toilet per twenty residents.)

“The landlord that we dealt with was actually leasing the floor so the people living there were technically subleasing,” said Henry. “I was in the first group of 17 to move there in June 2014, and I know there’s one or two of the original people still there, but otherwise all new people.” Despite the boarding-house atmosphere, “people did hang out in the common area a lot,” said Henry. “Some good groups of friends developed.”

In this era of mass customization, leaving even small apartments in conventional buildings deliberately unfinished or imperfect — and therefore open to modification, by adding more bedrooms and more occupants — has become more and more common in contemporary apartment buildings. Temporary walls have become a typical fixture of today’s real estate market in New York and are now often built without legally required permits. Stonehenge Properties, which owns twenty-three apartment towers in Manhattan, has been targeting their advertising at recent college graduates, encouraging them to turn one-bedroom apartments into two and three in order to afford rent, because “temporary walls can make room for more roomies.”

During my 2014 bout of apartment hunting, I answered a posting for an individual room in Bushwick’s Tea Factory Lofts, where I was greeted by an eviction notice on the door of the apartment. Not only did this evoke an ugly scene with the prior tenants, but the room being rented out did not yet exist. In the vacant apartment, construction workers were busy building two windowless cubicles adjacent to the one legal, windowed bedroom. The new cubicles, which would have small glass transoms that let in a modicum of light but didn’t open for air, were to be rented for $900 a month.

The Bedford Lofts, a newly constructed luxury rental building in Williamsburg, is an example of this type of marketing gone ironically wrong. According to its website, the property, where a studio apartment rents for $5,250 a month, offers “sumptuous and brightly lit living spaces, dramatic windows, and spectacularly flowing, fine-art-allowing (and often inducing!) open-floor plans… [that] have the power to lift your spirit after a hard day’s work and awaken the deep-seated artist.”

When residents began to move into the building in December 2013, they didn’t realize that a raw open layout was part of the deal; in the four-bedroom that resident Lauren Holman had leased, none of the bedroom walls had actually been built. Leaks plagued the apartment, there were no gas lines, and electrical wires for air conditioning and heat were sticking out everywhere.

When the walls did finally go up, they were built in strange configurations, with one bedroom missing a window entirely. A building inspector visiting the apartment said that if he reported everything he saw, particularly the windowless bedroom, “everyone would have to evacuate immediately.” On Thanksgiving eve 2015, the Bedford Lofts building was completely evacuated for much deeper-seated conditions “imminently perilous to life,” particularly “the installation of substandard structural steel columns, trusses, beams, welds.” This was a far cry from the thick-trussed, brutally strong, industrial cast-iron architecture that had attracted many early SoHo residents.

Despite today’s overwhelming profit motive, a pure type of ingenuity survives. When young inhabitants are able to settle together in one place and stay there for a while, carving out living space by hand can create a sense of creative common purpose. A few loft-dwellers still manage to turn life into art, such as Serban Ionescu, who has taught architecture at Rochester Polytechnic Institute. With his roommates and some funds from their unemployment checks (it was just after the crash of 2008), he built a colorful, fanciful collection of cubbies and bedroom spaces that put most shabby “tree houses” to shame.

“As for living together we grew together, through making art and installations together at first and then to large Parties, cooking, whisky making, cats,” he said.He displays the result as an example of his design work on his website, titling it “The Miner and a Major.”

Unfortunately, without thousands of subpar rooms in existence, many people would probably not be able to gain entry to New York. But the landlord creators of the subpar rooms that are the tickets are occasionally reminded by the Department of Buildings that they are not above the law. The McKibbin Lofts have received violations for illegal subdivisions, lack of egress and even hotel use. Whenever justice is “served” in this way, the evicted tenants, often unaware of the illegality they have stumbled into, are the ones who suffer — uprooted, homeless, sometimes for months. Those already entrenched in loft living need education and leverage against landlord greed.

The ideal of “living like an artist” has deceived some into living in worse conditions than their forebears, whose exposure to grime and precarity once upon a time was at least inexpensive. These days, you might be better off just getting a room in a regular apartment in New York — that is, if you can afford it.

Rachel Pincus writes about technology, design and urbanism. She lives in a “normal apartment” with roommates now and likes it just fine.

Can James Patterson Teach You How To Write A Bestseller?

He famously doesn’t even write his own books.

The first and clearest lesson from James Patterson’s MasterClass on writing — a three-hour webinar that costs $90 — is that James Patterson is a nice guy. Dressed in a brown velvet blazer and navy blue t-shirt, with his New York-accented voice, James Patterson, or “Jim” as my fellow MasterClassers like to call him, emits warmth. He opens his class with a joke — “Hi, I’m Stephen King” — and then immediately explains exactly what this opening joke is supposed to mean. Still, you want to hang out with him. You want to drink with him. He has an untroubled manner.

You don’t exactly meet James Patterson, though. Instead you get to hear his ideas about writing — not the worst way to spend 180 minutes, but not enlightening or surprising to anyone who has thought about writing in a serious way. Which is a shame, because when a man who has sold somewhere around 250 million books says things like, “If you want to make money” — you want to know what’s on the other end of that sentence.

I agreed to take this MasterClass because I was hoping to tap into some of that James Patterson magic. I write thrillers. I’d like to sell a few million copies of my next book. Also, the Awl said they’d pay me to take it.

The course is broken up into twenty-two lessons. The lessons have titles like: PASSION + HABIT; RAW IDEAS; PLOT; RESEARCH. The format is simple: James Patterson is staring into the camera and talking in a seemingly unscripted way about his ideas on these subjects. He tells you things like, Plot is action happening to a character. Or, Moving the story forward is the most important thing.

Each lesson has its own page, with an embedded video on top and a comment section called “Lesson Discussion” below. The discussions, frankly, were a little heartbreaking. People asked things like, “Does anyone know a coroner I can talk to?” Nobody replied. Students made profiles. They had pictures of themselves. Some of the pictures looked like glamour shots, or author photos. It made me wonder if people were using the MasterClass to date. One of the student’s comments seemed polished in a corporate kind of way and I started to suspect he might be a plant from the James Patterson / MasterClass corporation. But when I opened another window and looked him up on Facebook — there he was, eating food in Florida. Was this class making me paranoid?

Another heartbreaking thing that the students do is paste random parts of their stories, without comment, into the lesson discussions. I get it. We want people to validate our writing. I followed suit and pasted the first paragraph of my new book. Sadly, nobody liked it, or commented. I refreshed the screen a few times — nothing.

One of the most persistent rumors about the writer James Patterson is that he isn’t actually a writer. People argue he’s just a franchise, that he employs people to do the writing for him, a work strategy that would, in theory, make it hard for him to teach the craft even in a webinar. He confronts these charges head on in one of the lessons: ON USING A CO-AUTHOR. We meet two of them on screen, a man and a woman, and they appear quite happy with the arrangement: James Patterson creates detailed outlines while they do the actual writing of the book. (Patterson is a huge fan of outlines, dedicating two different lesson videos on the subject.)

Personally, Patterson’s process doesn’t bother me. The fact that he doesn’t seem to know that most of us can’t afford to hire co-authors — that is a problem. In general, the discussions on craft found in these twenty-two lessons are shallow, but friendly. There were plenty of times where I found myself nodding my head, but there weren’t any times where I found myself saying, Huh, I’ve never thought of that before.

On EDITING, he says, “Write, write, write it again. I do nine, ten drafts.” Okay.

In the BUILD A CHAPTER lesson, he tells us that he writes, “Be there,” on top of his pages as he goes. A reminder to smell, and feel the scenes. I actually kind of like that.

Another decent line: “Pace will pay the electric bills.” As a thriller writer, I agree with that!

On making complicated villains: “Your reader is going to know your characters maybe better than they know their own wife.” Really? Okay. But how do we do it?

At another point, during the OUTLINE PART 2 section, I started zoning out a little. My eyes drifted over toward my cat. Mr. Patterson pulled me right back in by saying, “Once you have the outline, start writing dude, you’re ready.” It was that dude that woke me.

Perhaps the most disappointing moment came when — during his section on ENDING THE BOOK — he announced that he was about to give a big reveal. He promised he was about to tell us something “worth the price of admission.” I found myself sitting up in attention. This seemed like it was going to be good. We all struggle with endings. Instead, what he gave us was: “Write down every possible ending, and go through them and pick the most outrageous one that makes sense, and go with that one.” Wait, what?

I finished my three-hour MasterClass in two sittings. The class’s stated goal was to “set out to write a best-selling book.” But the actual experience of watching James Patterson riff brought up a different central question: Why is James Patterson so comfortable with himself?

That’s what this thing is really about, beginning with the idea of looking into a camera and talking unselfconsciously for three hours. That would make me crazy. But not him. To his credit, he can do it effortlessly. But it’s not just talking about writing that comes so easily: He tells us how writing is always fun for him. It’s always great! It’s play! We don’t hear about any struggles. There is no self-doubt. He even says he agreed to do this very class because he’d never done anything like it before. It seemed like a neat challenge.

The only sign of struggle we get is a story about seeing someone pick up his book in an airport and watching them set it back down. “Oh man,” he says. “What’d I do wrong?” He then flashes a defiant look at the camera. “Or what’d my book designer do wrong?” He never expresses any doubt about his own writing. And why should he? He has sold over 300 million books.

I liked when he talked about his personal life. He said he was most proud of his son, which made him seem like a great dad. He says he hugs his son, and kisses him everyday when they’re together.

At one point, he tells us that his grandfather used to say, “Jim, when you grow up, whether you become a surgeon, or the president, just remember you have to be singing on the way to work.” It isn’t difficult to picture James Patterson doing that. But is that what we really want from our novelists? Even our commercial ones? Should they be singing on their way to work? I don’t know that they should.

In this MasterClass, Patterson makes his biography seem like no time at all passed between his first book, The Thomas Berryman Number, which came out in 1976, to his breakout hit, Along Came a Spider, in 1993. He wrote five standalone books during that time. There was a six-year fallow period between Virgin (1980) and Black Market (1986).

What was he doing during those six years?

That’s what I’m curious about.

Patrick Hoffman is a writer and private investigator based in Brooklyn. His second novel, EVERY MAN A MENACE will be published by Atlantic Monthly Press on October 4, 2016. Follow him on Twitter: @pdchoffman

Let's Talk About The Worst Song Of All Time

Do you know what it is?

Every time you think that they have finally run out of things to orally historicize there is yet another oral history just waiting for you.

We Built This S#!tty: An Oral History of the Worst Song of All Time

I would complain about this but I am as bad as everyone else with the clicking and the sharing and even the complaining, which in our idiot era is just one more way of clicking and sharing, those being the only things that matter. (I sent this around to some friends from high school yesterday and one of them responded that he’d like to see an oral history of the ‘80s TV show “Buck Rogers in the 25th Century” with Gil Gerard and Erin Gray, which we all agreed we’d read the shit out of before the conversation devolved into a series of admissions of pre-adolescent yearnings for Erin Gray, in case you’re wondering what straight white men of a certain age do during the day now. Also I wound up with the theme to “Silver Spoons” stuck in my head, so look at me more as a figure deserving your pity instead of your disdain.) I’m sorry I read the whole thing, but I won’t pretend that I didn’t.

So listen, Starship’s “We Built This City” is a terrible song. Of this there can be no dispute. There is no level of irony or nostalgia that can make it in any way tolerable. I bow before its awfulness. But hear me out, because what I am about to say may strike you as controversial, perhaps even abhorrent, particularly if you are young enough that you had not yet attained consciousness at its point of origin, but there is a song that is considerably worse than Starship’s “We Built This City,” and that song is Journey’s “Don’t Stop Believin’.”

“But Al,” you say, “I’ve sung that at karaoke!” “But Al,” you protest, “it’s an American classic!” “But Al,” you implore, “the end of ‘The Sopranos!’” Listen: Fuck karaoke, fuck America, and fuck you, and also don’t call me Al, you fuckin’ Journey lover. The only thing that made “Don’t Stop Believin’” the natural choice for the end of “The Sopranos” is that it is a song about murder: in the show, the murder of Tony Soprano, in real life the murder of critical faculties and a sense of shame. “Don’t Stop Believin’” is a lyrical atrocity, a musical miscarriage, and a vocal irritation so persistent that after a while you know you need to get it looked at by a professional. There is nothing redeeming about it, not even the fact that it is not “Open Arms.”

Yes, on a technical level Starship’s “We Built This City” may be slightly more objectionable than “Don’t Stop Believin,” but the latter’s continued and baffling popularity, particularly among people who would otherwise be horrified to publicly admit that their favorite meal is a big bowl of shit washed down with a glass of warm piss, which is essentially what you are saying when you say you like “Don’t Stop Believin,” pushes it up past Starship’s “We Built This City” in the Worst of All Time contest. I’m horrified that we even need to have this discussion. It is a bad, bad song and you should all know better. Now that you do, please don’t make me bring it up again. I’m just very disappointed with you.