Found In Translation

Exploring love and language in a new memoir by Lauren Collins

When in French, a new book from New Yorker staff writer Lauren Collins, is an exploration of the way language shapes us, and the ways we shape language. The premise intrigued me; my affinity to France is physical — I lived there for ten summers, and I return as often as I can. I am pulled back, time and again to an old, slightly shabby, converted barn called Les Marroniers in the Black Mountains near Carcassonne in the South-West of the country, where my parents now live permanently.

The simple, red-on-cream cover of When in French brought to mind the label on a swish bottle of red from an esteemed vigneron. I was expecting, wrongly as it turns out, a rustic memoir of the wiles of the locals in a small French village, and was willing to hate the book vehemently if it contained one droll waiter in a candlelit auberge or overly fastidious town mayor, presented with grand hyperbole for the amusement of Anglophone readers.

Happily this urban memoir contains none of these clichés, instead telling a story at once deeply personal to Collins and far-reaching, incorporating history, psychology, linguistics and myth in search of an answer to the overwhelming question; what does the language we speak say about us? And how can we truly communicate with those we love without the frame-of reference which is a shared language? Through personal incidents, Collins illustrates the fallibility of language, the way in which it is all too human a construct to not be hopelessly flawed. However she also engages us in the story of the French language, which came into being bloody and embryonic, as the omen of a fratricide, the key players in which come with names such as “Louis the German,” “Charles the Bald,” and Lothair.

A self-described ‘preppy’ girl from Wilmington, North Carolina, Collins’s only experience of ‘abroad’ as a kid was a trip on an Epcot-Disney World boat-ride where along with her family she “rode a marionette carousel” in Mexico, “before proceeding southwest to the Teashops of China.” This journey stayed with her, but a family superstition about travel linked to the death of her maternal grandfather, who died on a flight from Philadelphia to Erie, meant that Collins did not leave small-town America for many years.

The book is therefore full of Collins’s amazement that she ended up living in Geneva, married to a French man she met in London. She had turned to London for her adventure of living abroad due the commonality of language — as a writer, words were her agent and English was her currency. To end up living in a foreign language seemed at once strange and wondrous to Collins, rendered as she was, an alien in the medium she knew so well. Rather than avoiding cliches as she had all her life, she sought them out, finding it “such a happy thing to cling to cliché”:

How is one to know that inclement almost always goes with weather; that aspersions are cast but insults hurled; that observers are keen; that processions are orderly; that — as someone apparently decreed in the early years on this century — emails are to be shot and drinks grabbed? In English I strained to avoid such formulations. But, in French, conformity was my goal…I was trying to join in, not distinguish myself.

Collins’s gift for language is apparent throughout the book, where her strange and concise similes describe feelings, people and objects, neatly enough to make you exclaim, ‘Yes!’ After only half a chapter, I could only imagine how marooned she would have felt outside the native tongue in which she communicates so beautifully, often distinguishing herself.

Yet it is Collins’s skill with language, her fascination with how languages work, and why she was left simultaneously fascinated and marooned when removed from her birth tongue. She savors the strangeness and the pithiness of language. To be a third or fifth-wheel in French is tenir la chandelle — “to hold the candle” — she tells us. This phrase reminds me of a Scottish university boyfriend with a wandering eye, who after referring to “a racing-car blonde,” would add, as a sop, “of course, she couldn’t hold a candle to you, my dear.” The idea of candle-holding in different languages appeals to me, as it does to Collins, as I imagine a Wee Willie Winkie, running not through the “toun” but through a babel of languages.

What history, she wonders, has created this new language she finds herself inhabiting, which cultures have collided to chisel away surplus words and add others? How does language — the sole barrier between Collins and her husband, Olivier (Oh-lee-vyay) — make them the people they are? And does something essential change in you when you learn a new language — akin, perhaps, to a religious conversion?

With a journalist’s curiosity, Collins sets out to answer these questions, profiling languages (mainly French and American English, though others have their sound bites) as though they are living celebrities who she is on assignment to interview. (She has profiled Michelle Obama and Donatella Versace; profiling living languages seems almost a natural next step.)

“There are two schools of thought,” Collins says in a presentation to her French language class in Geneva, “one that suggests that each language expresses itself uniquely, another that holds that all languages are variations on a universal theme.” Collins gravitates toward the former theory: that languages are individual, and while they may be channels for expressing our universal humanity, they are nevertheless their own beasts.

French reveals itself to Collins as a language of words which are “impressionable, a little bit fickle, behaving differently according to whom they’re with.” She continues, “A French word, if all its friends did, would definitely jump off the Brooklyn Bridge.” Collins also explores the relationship between language and memory, citing Nabokov, who found that only through writing in Russian could he summon certain feelings in memory. The incidents he could render in any language, something which happened could be translated, but a memory of something felt was different.

As an Englishwoman whose parents live in France, my own experience of learning the language has been less rigorously cerebral, and more of a natural journey where the language seeped into my consciousness as I lay by the lake with friends, or chatted at café tables, or tried to eavesdrop on the conversations between my parents and their friends. I find the language beautiful, but I had not considered properly, deeply, how it had developed, how languages grow in sync with the cultures they represent, and how by speaking a different tongue (as Collins points out, the use of the word tongue, as opposed to say ‘ear’ is telling — to know a language you must do more than hear, you must partake in speech) you are entering a different culture. You eschew one history for another, disrobing part your identity to identify more with an other. To speak a foreign language is to make a sacrifice, but also to acquire a new facet.

To me, French has always seemed simultaneously spontaneous and refined, whereas American sounds like language spoken in italics; a sanitised, urgent, splashy language, slanting forward with a uniform urgency. When Collins writes about Olivier’s reticence in use of language, she compares him to the wife of an American executive who describes herself with the kind of hyperbole with which I, as an English girl, have rightly or wrongly come to associate Americans. “The third line [of her Twitter bio] — ‘wife of an awesome guy’ — struck me as too much and too little, overdone and neutered at the same time.”

Olivier, in comparison, holds some of himself back, both in language and in life, measuring his decisions with care. Collins was to leave him at one point, when she felt he was unable to properly commit. The issue was at least partly one of translation, a tussle to understand one another, not only linguistically, but culturally. Through learning Olivier’s language, Collins was able to know him better, overhearing his “true voice” on the telephone for the first time four years after meeting him, but she has also gone on a cerebral journey of self-discovery, which she shares beautifully in When in French.

I recently went to a dinner party with friends of my parents—Tyler is Scottish and Martine is Tunisian. Like Olivier and Lauren, they had to navigate the choppy waters of love in a different language, learning the alien words, sounds and sentence structures as they learnt about one another. Now in their sixties, with three grown-up children, they have reached an understanding of one another, talking in the shorthand of long-together couples. Tyler is Ty, and Martine is Tin, but only to one another. They have just found a buyer for their French home, having decided to move back to the UK where their children and newborn grandson live. Martine is optimistic about the sale, but Tyler said, “there is many a slip, twixt cup and lip.” She was puzzled.

“Twixt?” She tried the word out. An articulate woman who speaks beautiful English, she found the throwaway use of an antiquated word strange, bordering on incomprehensible. Her flawless English (the type spoken almost solely by non-native speakers) did not take to this deliberate but casual use of “twixt.” I thought of Collins and her newfound language, and wondered what odd rough-edged jewels of French she is still yet to find and wonder at, turning them over in awe at their absurdity.

When in French is released in the US on September 13th. An excerpt published by The New Yorker is available here.

Suggestions for Billy Joel's Madison Square Garden Residency in 2017

In case he wants to spice things up.

by Christy Admiraal and Stephen Mulder

Nearly three years ago, in a move called “unprecedented” and “historic” by Rolling Stone, Billy Joel announced he would play Madison Square Garden once a month on an indefinite basis. Mr. Joel shows no signs of stopping, and though the songs he plays each month are undeniably classics, one wonders if the Piano Man might benefit from a few variations on his typical repertoire.

January

Mr. Joel performs wall-to-wall Elton John covers. After the second encore (“Levon”), he teases the audience with the opening notes of “Piano Man,” then throws back his head, laughs, and plays “Your Song.”

February

Mr. Joel wears a blindfold during “Prelude/Angry Young Man,” which he plays twice in a row.

March

At the top of the show, Mr. Joel promises in no uncertain terms to throw a $10.50 Heineken at anyone in the orchestra section who yells “Uptown Girl.” He then follows through as many times as necessary.

April

The saxophone solo in “Just the Way You Are” is extended to 90 minutes.

May

Mr. Joel gives the Beau Brummell look exactly one half a chance.

June

After performing “Tell Her About It,” Mr. Joel proceeds to tell the titular her about it. At length.

July

Three words: Attila reunion show.

August

Mr. Joel performs the entire concert in character as Dodger from Oliver & Company and claims to possess “street savoir faire” on multiple occasions.

September

Mr. Joel performs covers of Billy Joel covers, including, but not limited to, Adele’s “To Make You Feel My Love,” Beyoncé’s “Honesty,” and Me First and the Gimme Gimmes’ “Only the Good Die Young.”

October

The show closes with “Piano Man,” but the lyrics are entirely improvised with an all-new cast of characters, each with a more elaborate backstory than the one that came before it.

November

Mr. Joel gives up on the piano entirely, relying on vocal accompaniment from Michael Winslow of Police Academy fame.

December

During “We Didn’t Start the Fire,” Mr. Joel starts an actual fire.

Christy Admiraal and Stephen Mulder met in college 10 years ago. Now, with Christy in New York and Stephen in Michigan, they enjoy a long-distance friendship via Skype and Ticket to Ride Online.

Beacon, "IM U" (Tomas Barfod Remix)

This will be one of the good days.

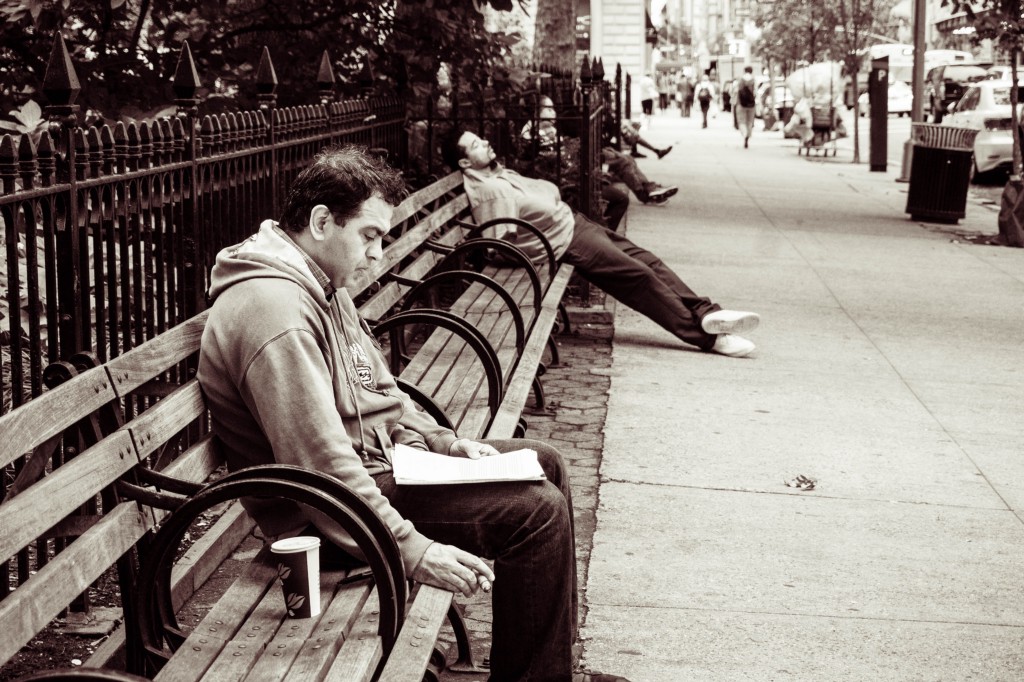

There are about four perfect weeks in New York City, but they spread out the days over the course of the year — usually around spring and fall — so that you never quite know when they’re going to happen. Today appears to be one of them, though, so make sure you get a little time outside to enjoy it.

Here’s a remix from the Beacon album that came out back in Februrary. If you missed it then or have just sort of forgotten about it as other stuff cycled through you should go back and listen again, it was terrific. As this day is supposed to be. Enjoy.

New York City, September 8, 2016

★★ Reflected sun coming back from the west threw shadows of upraised cameraphones onto the new kindergarteners as they lined up in the schoolyard. The march along the back side of the building passed through dappled shade. Yellow-gray clouds were cluttering the east, but nothing came of them. By dismissal from the half-day, it was plain hot. Once again it was a mistake to transfer at Times Square to cut down on the walking afterward. “Where’s the fans at?” a man said loudly, making his way along the ever-more crowded Broadway Line platform. “They should have fans down here!” Sweat rose and the announcement blared something about a signal problem. The air stayed thick all afternoon and evening, scattering the late light.

Eola, "B and O Blues"

Outside is bad.

A correspondent recently accused me of only continuing to write so that I could “force your music tastes on your fellow New Yorkers.” This suggests that I should not be writing anymore (true) and that I am disinterested in sharing my sonic aesthetic with anyone outside of Manhattan (false). But, yeah, sure, when I hear something I like to pass it along. So even though I have already suggested some music for you to enjoy today, I would also like to point you this way:

“Edwin Mathis White,” the promotional copy tells, “creates a capella DIY gospel as Eola using loop stations and vocal processing effects pedals recorded to tape.” However you describe it it is eerily catchy, and as those of you here in New York — goddamn it, I guess they were right — slink away from work into the disgusting climactic glop that awaits you out there, it seems like an appropriate soundtrack. Enjoy.

What's Pink And Orange And Yellow And Blue And Purple And Viewed All Over?

State of the Media, 2016

“While there are myriad challenges facing the media companies of today, combatting the power and market share of the social media giants — often called ‘the platforms,’ with an increasingly ominous tone — seems to be top-of-mind, and came up repeatedly throughout the [Digital Media Strategies 2016] conference…. Not every publisher in attendance expressed dissatisfaction with the state of publisher-platform relations. Business Insider President Julie Hansen wowed the crowd with slides showing the massive reach of videos the company’s Insider brand has produced on Facebook, on topics like rainbow bagels and melted cheese.”

No, no, I’m fine, it’s just allergies.

Just A Few More Hours in Cambridge, Massachusetts

Let us re-examine.

Have you heard of Cambridge? The Harvard one, not the England one. It has a lot of colleges in it because of Boston and it’s old. The New York Times wants to make sure you didn’t miss it in case you’ve never consumed any popular culture or somehow have never met a person from the suburbs of Massachusetts, which is frankly statistically impossible. So they did one of those “36 Hours in” features for the only time of year Cambridge is actually tolerable, weather-wise, except not people-wise, because it’s overrun with students coming back to class and pretending to care and managing impressions and actually going to class. And now for my disclosure: I was born in Boston, spent my early childhood in Watertown, and attended Harvard College. Most importantly, I lived in Cambridge during the cruel and perfect summers and got the hell off campus.

Founded in 1630, the venerable college town of Cambridge has long been one of the nation’s intellectual centers. Anchored to the banks of the Charles River by both Harvard University and the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, the city blends its storied past and erudite character with a rich serving of arts and culture. Today, the stamp of gentrification on Harvard Square and the gleaming biotech development flanking M.I.T., a.k.a. “Genetown,” make it harder to tune into Cambridge’s legendary countercultural vibe of used bookstores and punk rockers. Still, the outward-looking citizens, known as Cantabrigians, keep finding ways to express their funky, geeky flair, be it via political protests, copious bike lanes or science-driven cuisine and mixology.

Oh my God. What is this pamphlet language? Did you know people in Cambridge are geeks? Have you ever really wondered about why? Did you know that Harvard is a strange blend of rich old families and nerdy nerd nerds? But mostly money and bricks?

Many visitors tour Harvard Yard. But why not M.I.T.?

Because M.I.T. isn’t cool, it’s extremely dorky. Please don’t @ me.

What better way to taste the brainy shock waves of Harvard Square, Cambridge’s commercial and spiritual epicenter, than to sample its indie bookstores?

Help me. No one wants to taste brainy shock waves, which sound more like something they study at Caltech anyway (and I bet they’re salty). Cambridge’s commercial epicenter is a black hole called “The Garage,” a filthy and sort of sadly lit mall-cum-food court for punk teens who are never there. It can’t possibly do half as much business as one of the seventeen bank branches surrounding it.

Stroll the loop of Brattle, J.F.K, Church and Mount Auburn Streets and you’ll find the Grolier Poetry Book Shop (the country’s oldest continuous poetry-only store), the Curious George Store (for children), Raven Used Books (literary and academic), the Million Year Picnic (indie and alternative comics) and Harvard Book Store (best all-around selection). Pop into Black Ink for eclectic and hipsterish gifts; Leavitt & Peirce, a circa 1883 tobacco shop, to stock up on pipes, pocketknives and chess sets

Wow rude to adult Curious George appreciators. No one has ever been inside Leavitt & Peirce. Good snub of the Coop, though. [Ed. note: the formatting in this “interactive” article is killing me; any typos or weird things are their fault not mine.]

Grab a coffee and a snack like garlic knots ($6) with pecorino and a red dipping sauce at Area Four. Or head over to the Meadhall gastro pub and beer hall. Perch yourself at its giant oval bar beset with banker’s lamps, and your jaw might drop at the 100 beers on tap, with new brews rotating in each week.

Coffee does not go with garlic knots. Beset means to trouble persistently or enclose, like, attack from all sides. The lamps shouldn’t be besetting anything unless you’ve been eating shrooms.

Okay sorry just a few more:

Hungry for humble or highfalutin? For a lowbrow Harvard Square institution, dine at Mr. Bartley’s, whose walls, festooned with Ted Kennedy portraits and Red Sox ephemera, resemble those of a dorm room. Burgers are named for famous folk and political issues, like the Big Papi, a double burger with Cheddar and barbecue sauce ($18.25) or Fiscal Cliff ($14.25), with bacon, blue cheese and spinach. Wash it down with an ice-cream frappé ($6.99).

Show me a dorm room with Ted Kennedy portraits and Red Sox ephemera and I’ll show you that you are on a soundstage in LA where someone is being very literal. A burger that costs $18.25 is neither lowbrow nor humble (which, by the way, doesn’t have a taste). Please don’t drop the word “frappé” like anyone knows what that means.

Oh speaking of film-set versions of Harvard dorm rooms, remember the Dunkin’ Donuts from Good Will Hunting? “How do you like them apples,” etc.? Yeah it’s closed now, and it’s been replaced by a ramen shop.

The only lodging options given in this article are either THE CHARLES HOTEL or the Mary Prentiss Inn, which is crazy because they’re a) never available, b) very expensive, and c) don’t stay in a hotel in actual Cambridge unless you’re staying with a friend or in an Airbnb.

11. NIGHT LIFE AND NERDOM, 9:30 P.M.

I would’ve spelt it nerddom, but that’s just me.

Anyway, there’s a lot more to pick at here but essentially I would like to register my disappointment with the need for anyone to go to some simulacrum of “Cambridge” as it is constituted by this article. Please, if you must go to Cambridge, do try to visit the Mount Auburn Cemetery, Toscanini’s, Darwin’s, and C’est Bon, the perfect liquor store. Other than that most everything I once knew has been replaced by something else, which is how things go in a “gentrifying” (????) college city (poor Lesley University, always overlooked). I am particularly disappointed to report there is now a “Brooklyn Boulders” in Somerville. Generally speaking point yourself away from whatever campus you’re nearest and keep walking. Don’t stop till you get to Crane Beach.

In Defense of Against

…and against “in defense of,” with Mark Greif.

In recent times, The “Against [X]” essay format — once so ravishingly savaged by Ivan Kreilkamp — has been supplanted in the click-bait chum-trough by “In Defense of [X].” No longer do we critique things: we insist on them. Sadder still, “In Defense of [X] (On Feminist Grounds)” has become the belle of the essay ball. If you wish to be vapid or vain or cruel to your friends, simply write an “In Defense Of” proclaiming your right to do so. Indeed, it would be antifeminist to against you over it.

Where is against, that blunt critical knife with which we slaughter our darlings? I think Kreilkamp scared us into settling down. (He called Sontag’s Against Interpretation “the mother of all contemporary click-bait intellectual polemics.”) Anyway, into this awful farm of sacred cow cultivation marches Mark Greif with a new book called, satisfyingly, Against Everything. I caught up with Greif to discuss it. Before we go any further, I must clarify that we have a professional relationship: Greif co-founded n+1, where I work as program coordinator, which means that I run their events.

It’s worth clarifying, because this is an n+1 book. It collects the essays Greif wrote in his twenties and thirties. “They were all basically for n+1,” he said, “though some of them I never even handed in.” The magazine was Greif’s imagined audience. “The journal’s existence and its readers were the only assurances that there would be people interested in this kind of thing.”

The essays are about ordinary things like “exercise, eating right, loving right, marriage and family, planning to have kids eventually, sex in the meantime,” and wondering whether one really believes “in the virtues of all these things as they are usually offered up.” Suffice to say, it includes Greif’s classic n+1 essay “Against Exercise.” It also includes “Octomom and the Market in Babies,” in which he takes up against everything you said in 2008. And so on. There’s a great piece about Thoreau, and one I didn’t like much about Radiohead. Zadie Smith called it “skeptical, contrarian” but “never cynical.” The essays are about the present day, or rather the very very very recent past.

The book is scattershot in subject matter but unified by the strong sense that we suffer “an intolerable volume of babbling and lying” in this life, as we try to make decisions about what the right thing might be. “How would it ever be possible to think what was right or desirable,” Greif said, “if people with dubious motives won’t shut up for just one minute?” So, these essays carve out a space of silence, of not listening to others. This is the true principle of “Against [X],” I think: a writer’s faith in critique’s power to create space, a void levered open for new knowledge to rush in and fill.

Each of these essays contains the germ of an entire book, which Greif knows. In “Against Exercise,” Greif had hoped to perhaps begin a grand treatise — Against Exercise: The History of the Gym in Modernity, something like that. Instead, this book is a series of very highly compressed, concentrated versions of books. Greif compared it to “a chain of bouillon cubes.”

About the only thing I hate about this book is its page on the Penguin Random House website. I hate it because Greif’s little bio leads with his summa cum laude degree from Harvard. Although I’m sure it’s just a publicity thing, I hate the insinuation that his fancy degree is what makes Greif worth listening to, makes his against worth more.

And yet we can do nothing about the fact that Greif is an associate professor at the New School, the fact that this job makes him that morbid thing we call a public intellectual. Greif went to Harvard, Oxford, and Yale. He got a PhD with the title “The Age of the Crisis of Man,” which was also the name of a hulking nonfiction book he published in 2014. One cannot doubt, therefore, that he thinks upon serious things. In that book, he addresses a historical question: “Why, when people run out of resources to articulate the most profound questions, do they start relying on sententious statements about ‘the human,’ and what does, or did, that manner of speaking do?”

Greif benefits from a sort of mutually reinforcing flow: highbrow cred from his academic status backs up his toothy essays, and the sharp humor of those essays make him seem like a professor whose work might be worth reading. Perhaps, then, we must redefine the “public intellectual” label to embrace this kind of academic, a writer who is undoubtedly a popular and good essayist and also a professor, for his sins.

Last year, Alice Gregory wrote in the Times that public intellectuals still exist but have become outmoded. Setting “moral and aesthetic standards” from atop credibility silos is old fashioned; making decrees on taste at all has become a little gross. The public intellectual’s true inheritors in the Internet Age, Gregory suggested, are funny people. “A joke,” Gregory points out, “seems uncalculated in its morality; to hear a good one is to feel as though you’re being told the truth.”

Gregory’s theory lets us see why “Against [X]” is the format we need. Critique is always a little funny. Greif’s tactic of standing alone in a room of thought in order to figure out why and how he is thinking the way that he does is also funny. Against Everything is the work of a gadfly essayist, not a windbag: in it, Greif is nasty and fun and also takes us to new and spacious places. Perhaps gadflies alone can survive the long winter of “Against [X].”

Josephine Livingstone is a writer and academic in New York.

New Grandaddy

Let’s run away from this week.

After four days that have felt like way more than five, this week has grown tired of whaling on you whenever it sees you. Be sure to run off while it’s distracted. RUN. RUN FOR THE WARM EMBRACE OF THE WEEKEND! ETC.!

Okay, music: Grandaddy’s Sophtware Slump has a very special place in my heart. It means so much to me that it is detrimental to my enjoyment of anything else by the band, because I am constantly comparing everything else to Slump and finding it wanting. But I need to get over it. There will never be another Sophtware Slump, and that’s okay, because The Sophtware Slump we will always have with us. There is plenty of space for other Grandaddy. Which is good, because they’ve just released two new tunes.

Here’s “Way We Won’t.”

Here’s “Clear Your History,” which is a great title for a song.

Enjoy. And savor every second of this weekend. The weeks don’t get any easier from here on out for a long, long time.