Faces of Death

A curious collection of famous death masks, from Audubon to Whitman

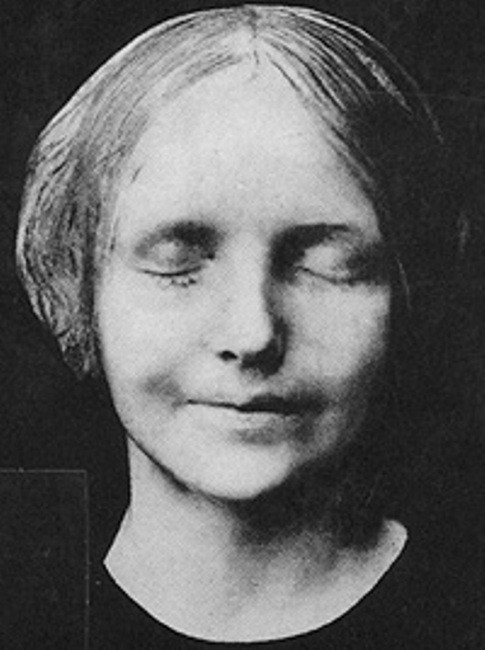

Before we learned to stave off death with antibiotics and pollution control, death was as much a part of life as living. People died of plague and chest colds, childbirth and drinking cold water; and when they died, they did it at home. From the late eighteenth century until the advent of photography, the dead were commemorated through casts of faces, or death masks: portraits in plaster, rendered quickly on a person’s deathbed. A death mask freeze-framed someone as they were in life, with the knowledge that their faces could capture something essential, and could speak for the living without language. (This was considered common, not creepy.) The world’s largest known collection of these plaster casts is located in the Firestone Library of Princeton University, on the north side of campus.

A summer afternoon in the middle 1860s, Laurence Hutton, the dramatic critic for the New York Evening Mail and later the literary editor of Harper’s, ducked into a small bookstore in New York City and noticed a boy attempting to sell a plaster cast of a face. The face struck Hutton as familiar; it was tarnished with age, he wrote in his memoir, but it was unmistakably the visage of Benjamin Franklin. Curious, he gave the boy a few shillings to lead him to where he found the face. The boy led him down Second Street and across the Marble Cemetery, where, waiting in the adjacent alley, was a pile of ash barrels containing masks of other familiar faces, including Oliver Cromwell and George Washington. All told, there were enough masks to fill a wagon, which he did. Hutton unloaded his treasure trove back to his house in the city, where his father, a former student of physiognomy, told him exactly what it was he had discovered.

After realizing the value of his hoard, Hutton returned to the alley full of remorse, but not enough to consider returning his trove. Mostly, he wanted to figure out whose collection he’d stolen. After knocking on most of the doors in the neighborhood, he learned that the previous owner of the casts was an assistant to the phrenologist George Combe. Upon Combe’s death in 1858, Combe’s wife ordered the removal of the “nasty, ghastly things,” and years later disposed of them in the alley. Conscience cleared, Hutton apprenticed himself to the study of death.

Hutton was well known as a collector. He stockpiled friendships as well as diaries, address books, and autographed copies of books from his famous friends like Walt Whitman, William Archer and Mark Twain. “Probably no man alive today has as many [friends] among American and English creators of things beautiful,” an article in the Princeton Alumni Weekly noted. (Hutton received his masters from Princeton in 1897 and later became a resident of the town). On his search for death masks, Hutton culled stories of the living and dead, journeying through alleyways and courthouses, through country roads and strange, dusty basements, all across the United States and on to Berlin and Paris and the Isle of Shoals, sneaking into crypts to make his own plaster casts. During this time, he mostly read obituaries.

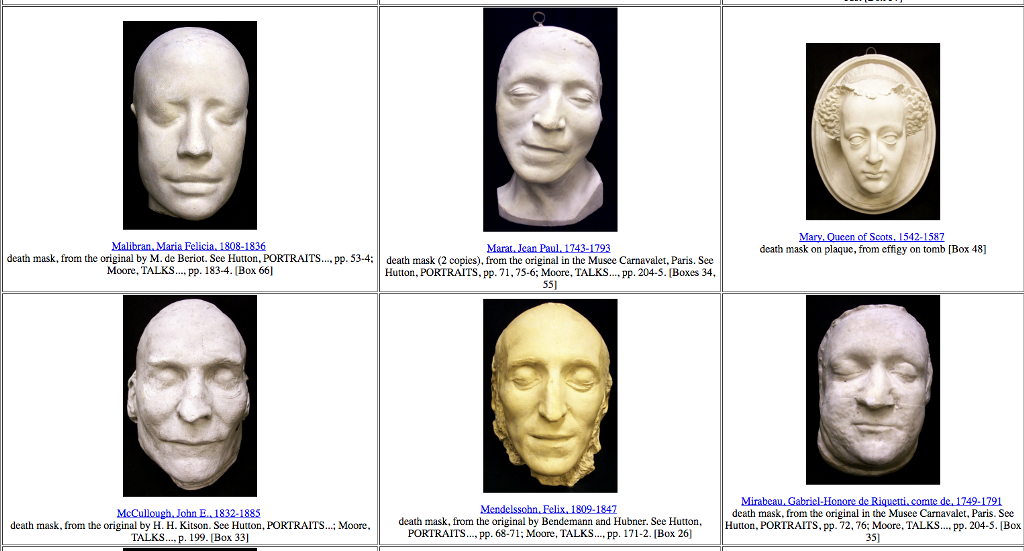

Hutton distilled his collection into the Laurence Hutton Collection of Life and Death Masks, comprised of original masks and copied casts from the originals, which he donated to Princeton University. He wrote two books on his collections, Portraits in Plaster and Talks in a Library With Laurence Hutton about the men (and occasionally woman) whose life and death masks he collected. (Elizabeth I. of England, Queen Louise, Mary, Queen of Scots, and a cast of Italian actress Eleonora Duse’ right hand comprise the death masks of women on display at Princeton). The stories center less around the legacies of these individuals, and more on how Hutton came to procure their death masks. Even so, reading the stories provides less insight into the collection than to Hutton himself. He is sometimes scientific (“Calhoun’s cranium is entirely different in shape”), sometimes extremely dry (“Their faces were smooth and shaven, but they were both far from being bald”), but often his scholastic rigor and appreciation for weird details suffuse his anecdotes with breezy wit.

Hutton’s writing suggests death masks access a universal truth about a person. This concept is reflected in the (dated, racist) science of phrenology, the brain science of divination, which supposedly allows masters of the craft to infer a person’s character through their skull shape. The truth of a person could be identified through their language and legacy, yes, but more by their face. Hutton returned to this idea a few times, telling the story of a man who looked at a famous poet’s death mask and told Hutton everything there was to know about Samuel Taylor Coleridge without ever reading his poems. “All casts tell truth,” Hutton wrote. “They must tell truth. They cannot help it.”

The Laurence Hutton Collection of Life and Death Masks sits three floors below Princeton University’s Firestone Library, entombed in a vault. The vault itself houses all of Princeton’s collections, from megalethoscopes to art prints, altogether the size of three football fields. It’s locked to those without special clearance, and requires a multiple keys and an iris scan to enter. The vault contains about one hundred faces, from Leo Tolstoy to Queen Elizabeth, staring up through their plaster irises, through their boxes, through the walls, and through the thousands of feet of people scrolling through Twitter instead of studying. They look like something like supine, less-precise busts.

Julie Mellby, the Graphic Arts librarian of Princeton University, moves with the care expected of someone who has made a career of handling delicate, breakable things. The plaster masks are extremely heavy and fragile, and since visitors aren’t allowed in the vault, she has to haul them up one by one. The largest ones, some made incorrectly with cement instead of plaster, take two or three people to lift. Before Firestone library existed, the death masks were displayed the in another building called East Pyne, where they were on permanent view for about twenty years. Not a week goes by that Ms. Mellby doesn’t get a call about the death masks, thanks to their modest fame in the world outside the university. Academics and tourists often call to request to visit the death mask collection, or arrange a visit with one mask in particular. These visits are bolstered less by morbidity, Mellby thinks, and more by genuine, scholastic curiosity. “It’s people’s faces,” she said. “It grabs your attention no matter what you’re studying.”

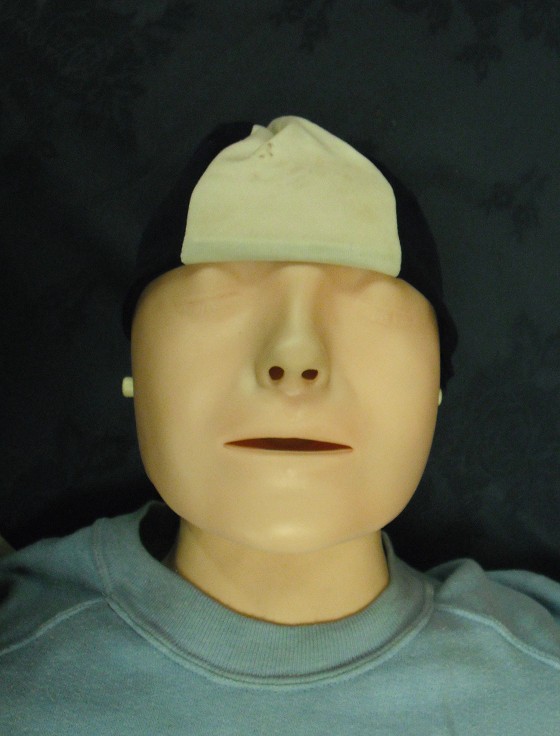

In nineteenth-century Paris, a lovely, tragic woman flung herself into the Seine. Her drowned countenance was so beautiful it was captured in a death mask known as “L’inconnue de la Seine,” forgotten only to resurface during the creation of the dummy used in CPR training. The androgynous, featureless dummy named “Resusci Anne” shares her face. Anne-Marie Tussaud, a French sculptor apprenticed to a physician, was forced to make death masks of murdered aristocrats during the French Revolution, including Marat, Robespierre, and Louis XVI. She later founded a wax museum in London, which spawned a few sequels. Yet Laurence Hutton’s collection is still the most famous and most complete of its kind, and bides its time in the basement of the library, a mausoleum of stories, which seems fitting.

We tell two sorts of stories about these death masks: the stories about the lives of those who are now frozen in plaster, and the stories of how those masks were acquired (which is of course a story about the collector). Stories are the currency of the living, even when the living is done. In life and in death, Laurence Hutton collected people — their bodies as well as their stories. Where Hutton’s own writings mention death, the tone is rarely sentimental, a quality he credits to overexposure. “I had lived so long in intimate intercourse with these things (…) that I had learned to look upon them with something like a hardened insensibility as to their actual significance,” he wrote in Talks. “But when it comes to the contemplation and examination of the dead faces of the men you have known and loved in the flesh it was a very different matter.”

The death mask is neither beautiful nor is it art; it’s the story of how a person came to wear the face they died in. Whether we would have learned more about Hutton from his own death mask is an impossible question, because he does not have one. (He had tried to make a life mask, an effort that proved unsuccessful. “I was willing to sacrifice my moustache for the cause of science,” he wrote, but it was impossible to salvage the mask after it snagged on his face. The mask was removed and broken gently with a hammer, which was not at all gently, and crumbled with a tap.) So we are left with his life, his words, and one hundred plaster faces, hidden behind lock and key.

Rachel Stone is the Editor-in-Chief of the Nassau Weekly. Her writing has appeared on The Toast, The Hairpin, The Awl and Narratively. She was once an Awl Summer Reporter.

A pictorial guide of the Laurence Hutton Collection of Life and Death Masks is available online here.

What Becomes A Legend Most?

If you thought Bruce Springsteen’s recent record-setting four-hours-plus concert was still not enough Bruce, you’re in for a thrill: on September 27, Simon & Schuster drops the man’s five-hundred-plus-page memoir, Born to Run. Even if you’re not a fan, you can’t reasonably question the book’s existence. Springsteen has had a decades-long stratospherically successful career spent writing and performing songs with lyrics intended to elevate the sorry human condition. Baby, he was born to be read.

If you have a favorite classic sitcom and the star is still alive, dollars to gluten-free doughnuts he or she has written a memoir in the last decade. Wondering what’s on the mind of a member of the rhythm section of your favorite seventies band? If he hasn’t already written a book, he probably has a deal. Of course, there have been celebrity autobiographies as long as there have been celebrities and vanity. But today I don’t think anyone is even pretending that the typical celebrity memoir is what God intended books to be: born of something like an authentic artistic impulse. The recent ubiquity of the modern celebrity memoir raises the existential question, Why are so many celebrities publishing memoirs now? And what makes a good one?

The first celebrity memoir I remember seeing on coffee tables was 1972’s The Moon’s a Balloon (titled for an E. E. Cummings poem) by the suave British actor David Niven. Niven was a raconteur and embodied genteel Englishness, and he knew how to inject the printed page with his charm and wit (sample line: his first sexual conquest had “a figure like a two-armed Venus de Milo who had been on a sensible diet”). So it was possible: literature needn’t be written by literary types. Game on.

I think it’s time for some ground rules: let’s agree that in order to elevate a celebrity memoir above a vanity project, it must have either (a) a great personal story resulting in (or from) a landmark artistic or cultural achievement and/or (b) David Niven–grade turns of phrase. A fabulous story written beautifully would be ideal, but let’s not be greedy: these are celebrity authors we’re talking about.

The celebrity memoir boom partly reflects an adult population that grew up with therapy, self-help books, and other invitations to look within. “There’s too much ‘me’ in Me,” my eighty-year-old grandmother complained about Me: Stories of My Life, Katharine Hepburn’s jeroboam of a celebrity autobiography when it came out to terrific fanfare in 1991. The belief that it’s vulgar to speak endlessly about oneself in public is, like my grandmother, long gone. Now an affront to a reader would be too little “me” in a celebrity memoir; what else are we paying for?

Like Springsteen, Hepburn justified her book’s existence by having led a life without antecedent in her field. Likewise, regardless of what you think of Chrissie Hynde’s 2015 memoir, Reckless: My Life as a Pretender, her book would have had to have sucked pretty royally (which it didn’t; it was a corker) not to have value as a testament to what it was like to be American and female in London’s rock scene in the 1970s.

Naturally, the celebrity memoir phenomenon also partly reflects a publishing industry in crisis: celebrity memoirs lure people who might not normally go to bookstores or check the “Books” icon on their Amazon drop-down menu; the idea is that sales to this demographic will somewhat offset the readership that’s being lost to one screen or another.

But beyond the death of modesty and the publishing industry’s understandable campaign to sustain itself, there’s another force pushing for the celebrity memoir today: celebrities tend to write (or “write”) when their careers are waning or at a low ebb — and note that we have an unprecedented number of celebrities now, what with reality television and Instagram and the rest of it. It’s good odds that when a celebrity produces a book, she is not at the height of her professional powers; otherwise, she would be off acting or being a chef or rocking out. If your star is burning bright, you probably won’t be appearing on Dancing with the Stars, as I felt uncharitably compelled to point out to my teenage daughter, a fan of the show.

But let us have something resembling a heart about this: some celebrities who have peaked (or their publicists) see in a book an opportunity to stay alive in a fickle, youth-besotted business. Before I became a writer, married a musician, and acquired a mortgage and two kids, I didn’t understand the economics of the creative life. I recall being flummoxed when I learned that a member of the Flesh Eaters, a favorite punk band of my adolescence, had quit the band to drive a city bus. Imagine how gutted I felt when Johnny Rotten did that butter commercial. (Loved his book, though.) It’s no coincidence that the celebrity memoir boom is happening at a time when there is absolutely no shame in doing commercials, which is, of course, what the celebrity memoir is: an ad for the self.

If you’re a celebrity who is neither a tested wordsmith nor a Serious Artist, your embossed name can still merit a place on the spine of a book, but you may have to be a little resourceful. Marlo Thomas’s Growing Up Laughing: My Story and the Story of Funny, from 2010, is a memoir interwoven with (good) jokes and transcriptions of Thomas’s interviews with comedians and comic actors on the subject of what makes humor work. I would bet a kidney that Growing Up Laughing arrived at this structure after Thomas submitted a straightforward draft of her life story to her editor, who broke out in a sweat, realizing that he couldn’t publish it as it was due to its adversity-free through line. Growing Up Laughing succeeds as a decent showbiz memoir because Thomas and her book team obviously cared enough about the enterprise to think up a way to enhance what would have been a tale of reader-repellant smooth sailing: the “me” became “we,” which meant multiple little stories in service to the big story of American comedy.

A less enthusiastic effort by a TV sweetie is Amy Poehler’s memoir, Yes Please. As Dwight Garner, a fan of the comic actress, noted in his 2014 Books of the Times review, the guileless Poehler plays her hand in her book’s preface: “I had no business agreeing to write this book” (meaning the idea wasn’t hers). Writes Garner: “Ms. Poehler’s slow drip of gripes (‘Dear Lord, when will I finish this book?’) breaks rule number one about comedy and about writing: Never let them see you sweat.” Garner gives Poehler points for honesty; I give her points for having apparently undertaken the book without a hired hand. (After all, talking into a recording device is writing the same way that listening to an audiobook is reading, although each can be a worthy endeavor.)

It’s curious to learn which celebrity authors looked for the nearest amanuensis. Despite being a single mother pinioned by children in the mid-1990s, Mia Farrow wrote 1997’s starkly lovely What Falls Away: A Memoir, whereas Marianne Faithfull enlisted rock journalist David Dalton to assemble 1994’s Faithfull, even though she is well read and considered a Serious Enough Artist to have taught at the Jack Kerouac School of Disembodied Poetics. (It’s a real school. Look it up.)

That Faithfull’s memoir was well received (as it should have been: as I’ve mentioned in the recent past, it was dishy but soulful) couldn’t have escaped the notice of her one-time partner in crime Keith Richards, who can be fairly held accountable for the musician memoir boom following the galactic success off his deservedly lauded 2010 memoir, Life. He can be forgiven for going the as-told-to route because what the journalist James Fox pieced together from Keith’s recollections is so tirelessly absorbing; the book retains a raconteur’s easy-flowing humor and the hint of English gentlemanliness underneath its overarching “Fuck off!” spirit.

The most interesting thing about Keith’s book’s success is how unremarkable his actual story is: while his has been a life of extraordinary achievement, it can’t be said that he had to tunnel through a mountain of seemingly insurmountable obstacles to get there. (Most of the adversity he experienced he brought on himself.) Life isn’t Coal Miner’s Daughter; Life is David Niven’s The Moon’s a Balloon with heroin.

Do you know what’s a far more cynical publishing trend than the too-often value-free celebrity memoir? The celebrity-authored (or “-authored”) children’s book. Some celebs do actually bother to write a story intended for children, but the hot new plague is the cross-merchandizing of song lyrics: the publisher takes the words to a living or dead musician’s classic tune for grown-ups, sprays them across the length of a kids’ picture book, hires someone to illustrate them, and calls it an extremely lazy day. Artistically, this gambit pretty much never works: even if they do rhyme, lyrics recited by a reader unfamiliar with the song don’t scan, and a chorus’s seemingly pointless repetition on the page is dizzy-making.

But economically, these books can be winners: adults tend to buy what they like for their kids. It should be noted here that Keith got aboard the kiddie lit train with 2014’s Gus and Me: The Story of My Granddad and My First Guitar. When I saw that book, I pictured an editor at a desk: “Life was a smash. We need a follow-up. Let’s ask Keith if he has anything left.” Baby, he was bound to run out of ideas. Now fuck off.

Nell Beram is the coauthor of Yoko Ono: Collector of Skies and a former Atlantic staff editor.

Soundscan Surprises, Week Ending 9/15

Back-catalog sales numbers of note from Nielsen SoundScan.

The definition of “back catalog” is: “at least 18 months old, have fallen below №100 on the Billboard 200 and do not have an active single on our radio.”

Matchbox Twenty’s Yourself or Someone Like You jumped EIGHTY-NINE spots in the last week TO NUMBER ONE. There isn’t a whole lot of news there except that the album is twenty years old, his wife is having health issues, Rob Thomas played at Red Rocks on Monday, and he apparently wants a twentieth anniversary reunion tour (who doesn’t, buddy?).

Speaking of anniversaries, the Ramones’ 40th Anniversary Deluxe Edition was just released; of its 1,492 copies sold to date, 1,468 were sold last week. Faith No More is back on the list and I had to Google again (sorry). There’s some sort of deluxe re-release going on and a teaser for a new video for a sort-of-new song? More importantly, had you ever heard of St. Paul and the Broken Bones? They just released a new album, so their old one is selling a few copies. Here’s a cool Tiny Desk Concert they did in 2014:

Finally, Halloween is around the corner, and apparently also the name of the artist listed on the collection, Monster Mash & Other [Terrifying] Tunes. Watch your back, Halloween; Joey + Rory’s A Farmhouse Christmas is coming down the pike.

1. MATCHBOX TWENTY YOURSELF OR SOMEONE LIKE YOU 5,215 copies

9. WIZ KHALIFA ROLLING PAPERS 2,669 copies

53. RAMONES 40TH ANNIVERSARY DELUXE EDITION 1,468 copies

55. FAITH NO MORE KING FOR A DAY/FOOL FOR LIFE 1,447 copies

98. FAITH NO MORE ALBUM OF THE YEAR 1,150 copies

160. ST. PAUL & THE BROKEN BONES HALF THE CITY 923 copies

168. HALLOWEEN MONSTER MASH & OTHER TUNES 907 copies

188. JOEY + RORY A FARMHOUSE CHRISTMAS 881 copies

(Previously.)

Leonard Cohen, "You Want It Darker"

Don’t worry, you’ll get it.

I remember in 2001, when Ten New Songs came out, I thought to myself, “Wow, I thought I’m Your Man and The Future were Leonard’s late period, but I guess this is it.” It’s rare that I’m wrong but in this case I was and I could not be more happy about it. You Want It Darker comes out next month, and it’s the latest entry in what at this point we can consider Leonard’s late period… but who knows? Maybe he’ll never die. I would be okay with that. Enjoy.

New York City, September 19, 2016

[No stars] Sounds of rain came on in the night. The morning air was suffocating. More rain began to fall as the kindergarteners and their parents lined up and squeezed toward the door for the rainy-day dropoff protocol. One adult’s umbrella in the crush poured water on the back of someone’s shirt two adults away. While the rain kept falling, the rain jacket was uncomfortably hot; as soon as the rain paused around midday, it was chilly enough to wish for the rain jacket on again. The rain returned. A tour bus rolled down the avenue with its cargo of loosely plastic-wrapped tourists. The last light of the ruined day came on as a ridiculous lavender glow overpowering everything, then deepened to an impossible fresh-blood red.

The Masterclass Collection

Who taught it best?

Online academic institute Masterclass promises “access to genius,” and the roster of instructors certainly includes some of the stars of their respective fields providing hard-earned lessons to anyone with $90 and a burning desire for wisdom. The Awl is proud to have sent some of our favorite writers to school. Here’s what they learned along the way.

Laura Olin on Aaron Sorkin:

Reeves Wiedeman on Serena Williams:

Patrick Hoffman on James Patterson:

Marian Bull on Usher:

Jesse Andrews on Werner Herzog:

Kelly Conaboy on Christina Aguilera:

You’re dying to know more, right? Well, don’t just pick one, read them all! These are the Masterclasses on the Masterclasses, and knowledge is just a click away.

Did You Inherit Loneliness?

Or do you just suck on your own?

Do you ever feel alone? Like, really, truly alone? And not just in those moments when you are by yourself, but even when you are surrounded by other people, sometimes while you are in the middle of a conversation, perhaps during moments of great intimacy? Are you overcome by a wave of sadness and separateness so sharp that it’s all you can do to turn your face away for fear that someone might see you cry, not that they’d understand, since you’re probably the only one who feels that way and there’s no one who can help you anyway?

Well, Science has been doing some research on loneliness:

Loneliness is linked to poor physical and mental health, and is an even more accurate predictor of early death than obesity. To better understand who is at risk, researchers at University of California San Diego School of Medicine conducted the first genome-wide association study for loneliness — as a life-long trait, not a temporary state. They discovered that risk for feeling lonely is partially due to genetics, but environment plays a bigger role.

So this is good for everyone who needs another reason to pin their problems on their lousy genes and those of you who look at your outgoing parents, with their strong ties and large group of friends, and wonder what went wrong with your own life, why you aren’t able to get even a few people around you to help stave off the agony and dejection that surround you in your solitude. It’s not just that you’re a sad, unlovable monster whose sorry social skills seem to drive others way, it’s also that you’re looking at how pathetic and pitiable your life is through a lens of perceived isolation. Either way, you’re all alone. Fortunately, capitalism is on the case:

If you’ve got the money, you can now Rent-a-Friend, pay for cuddles, or dine with strangers. Our reaction to these services tends to vary, in keeping with how intimate they are — cuddle parties seem weirder than dinner parties — but the basic trade-off of cash for connection is the same in each case.

And if you don’t have the money? Well, by the rules of the society in which we live, that’s your fault, genetics or environment be damned. You deserve to be alone. Better get used to it now, because you’re going to be by yourself for a long, long time until you’re finally welcomed into the companionship of the grave. Loser.

We Are All Just Pretending Not to Be Frightened

And other answers to unsolicited questions.

“Art really makes me feel stupid. I know I should like it, but I always feel like it is making fun of me. What can I do? Am I an unsophisticated moron?” — Artless Artie

No. You seem like a normal, thoughtful person. Art probably is making fun of you. It’s not your fault. That’s all that’s left for art to do: make fun of good, seemingly thoughtful people. Art can sometimes be fun, I think, or maybe that’s mostly nostalgia. Is fun mostly nostalgia? Remembering when something else was fun and confusing that for current fun now? Probably.

But, listen, it can be fun to walk around in Chelsea on the nights of many openings and all those different galleries between 10th and 11th or whatever, going up the stairs, back and forth, see what cheese they’re smoking across the street. Art is supposed to be fun, I think. Art can also be kind of pretentious and annoying. And it’s possible that maybe your tastes are banal. Or maybe everyone’s tastes are predictable. If you painted a Care Bear with a piece of bacon tattooed to its stomach you could probably hang that in MOMA right now. I’m as nostalgic as the next guy, but the golden toilet is probably not as good a piece of art as the crucifix in the urine. They’re both not great, but “Piss Christ” probably wins out as the classier gesture.

The American Artist broke bad with the American Art-going Crowd a long time ago. It’s an indelicate balance, the disdain artists must feel for the viewing public while also simultaneously needing something unwinnable from them: support, money, fame, cocaine, models, love, whatever. The art museum used to be the only place in town you could go and see naked people and have it not be like a weird orgy. Nope, that’s just art. Naked people everywhere. Eating pears. Reclined in fields. Walking down stairs. Bouncing as they go. Now art projects are like dumping crickets on you while you’re on the subway. Like every art project ever is like this. Go ahead and check. It’s your dime, pal.

So, no. You are not a moron. At least not for this reason. American Art has failed you. Feel free to mutter this loudly to yourself as you wander through galleries. It will make you immune to the shade American Art is throwing your way, with its sarcastic big blue blotches or whatever they’re doing these days. Just blow your Instagram photos up until they’re 6 feet tall and that’s every photography show in the world right now. Until we can once again lick the paintings in boundless solitude I say screw Art. Television is the only art these days. Feel free to mutter that wildly to yourself, too, as you march through all the different layers of nostalgia. It’s not true, but shout it at dinner parties anyway. Art’s not dead, it’s undead. The zombie apocalypse has happened! And it’s devoured you! Feel free to shout that, too. Like you’re in an art project.

“How scared is it OK for me to be?” — Afraid Dave

It really depends on how you deal with that fear. Fear can be great. I am afraid of losing my job, therefore I show up to work at the bookstore when I am on the schedule. I am afraid of making babies during sex so I come in my pants in like 10 seconds after we start making out. Yes, that was part of my plan. I was trying to do that. And you’re welcome.

If your fear makes you like a hateful annoying person, I am not for it. If it makes you think there is an us that can be v. them, that’s just not a mechanical bull I feel like riding. Or even having momentary clothes-on sex with.

It’s OK to be scared enough for you to call your mom a little more often just because you’re afraid that you’ll be killed on the subway by a crazy person with crickets who is really just doing an art project. Or frightened enough that you’re nicer to people.

I fall asleep every night and am surprised when I wake up the very next day. Still as me, in this same body. Does this happen to you? You’re like you for your whole damned life! It’s a very strange sensation and I don’t recommend it. I prefer to think that everyone else in the world is actually just playing a role, hopefully a different one every day. One day you get to be Bono, the next my bus driver. And that somehow it all centers around me in some important way. I don’t know why everything centers around me. My experiences are pretty boring. They mostly revolve around hot dogs.

So, fine. Be frightened. Everyone is frightened. We are all just pretending not to be frightened. Just don’t start a cult. That’s just a whole lot of responsibility you don’t want. Take it from me, The Great Zulgoth from the Planet Erwok. Let my tentacles of wisdom be your guide.

Jim Behrle lives in Jersey City, NJ and works in a bookstore and is no longer the leader of a cult.

The Nevada City Wine Diaries

Domaine Bousquet Ameri, Jardin des Charmes Rosé, Domaine Thierry Laffay Petit Chablis

2010 Domaine Bousquet Ameri

I bought this wine on Monday as a gift to myself for finishing a thankless task that ended in only the most minor humiliation. It is a 65% Malbec, 20% Cabernet Sauvignon, 10% Syrah, 5% Merlot blend from an organic winery called Domaine Bousquet near Mendoza, Argentina. Malbec is not native to Argentina; it comes from a region in France called Cahors, and has merely been revitalized in (and is therefore associated with) Argentina. If you see a red wine that says Cahors, it is a French wine made from Malbec, likely with a little Merlot added in. (I see there is also a blues festival in Cahors — I can’t imagine anything worse!)

The Ameri is a huge steamship of a wine, with a blaring air horn. It is purple and smells like you spilled a glass of expensive wine on the floor of an oak sauna. It would be nice to drink this wine from an enormous goblet in front of a rain-streaked stained glass window in a library at Oxford while an elderly Don banged on about the Iliad.

People like big wines. Americans especially like them because we like sugar and oak, and a lot of fruit gives wines a sweet taste we really just can’t help crave any more than we can help having begged our parents to buy Fruit Loops. I say sweet taste because you’re not really allowed to explicitly call wines sweet unless they’re classified as such — I will talk more about this later — at any rate, there is something pleasing in big wines, and indeed in this wine, that is about sweetness. But this winery is also at 4000 feet, so it has a lot of other things going on in it like acid and tannins because, very simply, where there is cold air grapes are permitted to develop flavors more complicated than sugary ones.

Big wines are generally not much in fashion right now with fashionable wine critics, and I have mixed feelings about this. Robert Parker, founder and editor of The Wine Advocate, has really championed these dark, deep, velvety explosive wines and really pushed winemakers, dependent on his rating system for sales, to pick their grapes late and let them languish in oak and to generally favor unsubtlety over subtlety. This is not good and anyone who thinks so is an ass, that said, the Ameri is dense, concentrated stuff and I liked it a lot.

I drank it over the course of three nights and shared some of it with Tor alongside a fat steak which was the other part of my “thanks for doing that thing no one will thank you for but you” and some of it with a woman at my office who asked “Wow, why is this so good?” I said, “Because it was expensive,” and she said, “You know you can get a really good Malbec at Grocery Outlet,” and I said, “I seriously fucking doubt that.”

Jardin des Charmes 2015 Rosé

Thursday night we were going to a party. The party was for a person who is obsessed with Phish and plants, so her party, I knew, would be populated by similar people. That afternoon, I stood in front of a mirror and practiced saying “I know nothing about plants” in as non-confrontational a way as possible. Then I went to Grocery Outlet to get wine.

I tried to find a Malbec but they only had one and it looked terrifying. I bought a rosé for $4.99, from the Languedoc in France. I have been to the Languedoc, I call it the Long Duk Dong. Does everyone do that? I tried to stop but I can’t.

I have bought probably six bottles of Languedoc rosé at Grocery Outlet this summer. They have all been fine, which is to say that they were dry and they tasted good cold. In my extremely limited opinion the difference between an undrinkable rosé and an acceptable one is that the former is too sweet and the latter is tasty if unremarkable. The difference between an acceptable rosé and a good one is that the latter is just tastier. It’s like the difference between sitting on some park bench and sitting on a bench in some beautiful hidden garden. And when you can get pretty good rosé for $5, it’s harder to get greedy about wanting something better. For me this is only true of rosé. To buy other wines, I would mortgage things.

My rosé was a very big hit with the plant people and I ended up Learning Things. The most important thing I learned was that the English Ivy growing everywhere here is invasive and very triggering to people who know about plants. “I see it everywhere, I can’t not see it,” one woman told me. “People are always talking about how pretty it is and I can’t not lecture them on how it just chokes and kills everything, because I just feel like they have to know.” I told her that was exactly the way I felt about supermarket Pinot Noir and we poured ourselves another glass of Grocery Outlet rosé.

2014 Domaine Thierry Laffay Petit Chablis

I am no expert on Chablis or any other wine but I am an expert in loving Chablis. Chablis is made out of Chardonnay, but it is not called Chardonnay because in France they name wines after where they’re from, not after the type of grape they’re made out of. I bought this wine from this dude Cal who owns the wine store here in Nevada City and wears shorts all year round. “This wine is very well made,” he said when he handed it to me, staring dispassionately out the window as he does when he talks about wine.

American Chardonnay — famous brands are Meridian and Kendall Jackson on the supermarket end, Kistler and Rombauer on the fancy end — tends to be fruity and oaky. It often tastes of butter. I will speak very, very generally here: the reason it tastes of butter is it often undergoes intense malolactic fermentation. So malic acid in the wine turns to lactic acid (milk acid) so that it quite literally develops creamy flavors. It is also aged in a lot of oak which makes it taste very toasty and kind of exacerbates the butter flavor.

Now, Chablis may also see malolactic fermentation and oak. But traditionally, it has not, and when it does, it is still (as it comes from a much colder climate) much drier and more restrained that American Chardonnay. American Chardonnay is like a tourist in a stretchy maxi dress taking pictures of the Eiffel Tower. Chablis is like a straight-backed school teacher in a well-cut suit with her blonde hair arranged in a neat chignon, forcing children to decline verbs. By the way, Petit Chablis is the crappiest form of Chablis, from the most unsung of its vineyards, but it’s still really good.

I drank this Petit Chablis over the course of four days. One night I drank a glass by myself, ate a piece of boneless organic chicken, and sobbed over season three of “Last Tango in Halifax.” The next night I shared some with Tor while we ate steak and I made his friend drink a bottle of shitty Merlot I’d gotten for free, because I knew he’d prefer it. The next night I came home and drank one glass in bed as I giggled over Thank You, Jeeves. And then, Saturday afternoon I had the last bit, sitting at a picnic table with my feet resting on Merle, gazing out over the natural world. I saw something suspicious on a tree and investigated. It was English Ivy. It will be destroyed.