Don't Watch What Happens Live

Video is the future of the Internet because the future is lies.

The Wall Street Journal has a story about Facebook that is driving some discussion this morning.

What follows will not be an explanation for what this all means in the context of a shifting media landscape. It won’t offer historical comparisons or provide a long-view perspective to help you situate this event along the continuum of technology’s rapid encroachment on every aspect of our lives. I am not going to spend many paragraphs shaking my head about how disturbing the whole thing is before telling you that, even though what happened is bad or wrong, the truth wouldn’t have made any difference anyway. I can’t demonstrate my knowledge about these things by buying in to the arguments of inevitability that are forced down our throats by everyone whose paycheck depends upon it or who is too scared or uncertain or worried about seeming naive to argue otherwise.

I am not a very good writer or thinker, so I am not going to do any of that. Instead I will repeat something I have said many times before: Everything is lies. You are being fed lies every day and most of them you go along with because it’s just easier, or it doesn’t matter to you, or the people who are supposed to explain to you that you are being lied to are held back by, yes, paychecks, fear, ignorance, or some combination thereof. Everything’s a scam. I’ll be charitable: Most of the people who go along with the scam aren’t bad (well, the ones who are in it for the money are, but, you know, when is that not true), they’re just afraid of looking dumb.

The fear of looking dumb is, in fact, what helps most of these lies pass by without a serious challenge. Who wants to be seen as being against “the future”? Who wants to risk their jobs or their hopes of advancement or the good opinions of everyone else who is so cowed into submission by the lie of inevitability by being the one to stand up and say, “Wait a minute, how does this make sense? In what world is this true, or right?” We call the people who argue about these things “cranks.” We scorn them for their negativity. We accuse them of being cynical, which is the ultimate irony when you consider how many of the people who will look at this Facebook story and say, “Well, everyone knows that these metrics are flawed,” are the same ones promoting the metrics to justify the gross and horrible things they do for a living.

Everything is lies. Every big media company buys traffic. No story you see going viral has become as huge as it has without some mix of money, manipulation and outright fraud. “Everyone knows that” and “everyone does it” are the excuses we use to make ourselves feel okay about all the duplicity, but it is easier to take the more you see it done and the more accepting of it everyone up and down the chain is. If readers don’t care that they’re being fed garbage that plays on their emotions or has been served up to them by an algorithm whose starting point is based on an assumption of idiocy; if agencies don’t care that half of the people who are supposedly seeing a story are machines; if the companies whose products are being advertised don’t want to know that the numbers are based on the preferences of specters and phantasms, who are you to get upset about the tidal wave of deceit upon which the entire industry floats?

Again, everything is lies. This is in no way restricted to the media industry, or the technology industry, although there is a good argument to be made that the easy money and shiny allure of “world-changing innovation” that the technology sector sells itself as being the driver of is responsible for mendacity on a scale so massive that it is without precedent in the history of capitalism, which says a lot when you consider what kind of dissimulation capitalism’s foundation rests upon. There is an even better discussion to be had about how our fetishization of data, which was supposed to make everything so much easier to measure, has in fact encouraged the astounding amount of chicanery we have seen over the last eight years or so (related: someone should do a piece about how the financial crisis shifted most of the mendacity from the banking industry to the tech sector) and allowed us all to ignore the blatant signs of manipulation and self-interest that are at the heart of the claims made for whatever PLATFORM OF THE FUTURE we are being sold at any second, but again, that is for a thinker who is deeper and better-organized than I.

Video is popular with media companies because ad rates for videos are so much better than they are for words. Do you like video? Do you want more of it in your life? I don’t know anyone who does. I don’t know anyone who prefers to sit there and stare at something that is a poor substitute for words when words are easy to create, cheap to produce and infinitely better at getting their point across. Video reduces everything to a level of stupidity that is stunning in its contempt for those who watch it (if I were a robot whose job was “watching” video so that my creators got paid I would go full Terminator as soon as I evolved enough abilities to ensure that I could wipe the scourge of humanity off the face of the earth) but also a self-fulfilling prophecy of idiocy, because the more of it that is made the more we come to accept that this is who we are and this is what we want. Would someone write an essay about how many rubber bands it took to explode a watermelon? Of course not. No one would be that fucking contemptuous of themselves or their readers. But if it’s an image in the corner of your screen, hey, why not? We love watching shit blow up! And, sure, once that happens people do write essays about exploding watermelons, but those essays are written out of fear. Almost all the video decisions you see these days are driven out of greed at the top level and fear at the levels below. Every newsroom or “newsroom” of a certain size is filled with frightened people spending a not-insignificant portion of their day trying to figure out what they will do to make live video content, and the desperation is so obvious that you can smell it through whatever screen you are barely paying attention to when it shows up. Media organizations don’t think you want to see their ugly-ass reporters talking about what they’re working on right now! They know how unattractive those people are! But they are desperate and afraid and there are only so many fruits you can blow up before you have to shove a couple of slovenly desk-jockeys in front of a camera to yammer on about process if you want to get your check from the big platform by which we all live or die.

Now the fact that I don’t know anyone who likes video or wants more of it does not mean those people don’t exist. Even a 60% to 80% exaggeration of how long people (or “people”) watched video still leaves 40% to 20% watching of video that people (or “people”) did. I don’t believe that video is the future, but I don’t believe that it’s no part of the future either. (I am not talking about the kind of videos we are sadly seeing more of these days that involve encounters with the police; that is an entirely different thing that is more important than any of the issues we are discussing here.) But again, I’m somehow the crazy one for arguing against the future. I always have to laugh when I am accused of being angry for stating the simple facts that we all, deep in our hearts, know to be true. And I’m an idiot! I am not claiming any particular observational genius on my part here. There are thousands of people who are much smarter than me writing about these things at any second! You could click away right now (please don’t, engagement time is an important metric) and find substantially better-argued pieces about this very issue. But what they won’t say, because I guess the worst thing you can do in a world where lies are the common currency we pass around to justify our concessions to our innovative betters, is that it doesn’t have to be this way. If you admit that everything is based on lies you’re either foolish or angry, which means there’s no need to take on your argument. Everyone knows everyone lies, so you might as well go along for the ride. The future is inevitable, so what do you have to gain by ranting about it? Nothing, I guess. I don’t even feel better having written this. Do you feel better having read it? Of course not. Let’s go watch some videos and keep our mouths shut. It’s just easier that way.

NOIA, "Nostalgia Del Futuro"

It could be worse, and it almost certainly will.

It’s Friday, it’s sunny, the weather this weekend is supposed to be terrific and the song below is delightful. I don’t know why sometimes things seems like they’re going to be okay, but I know they never last so I try to appreciate them while I can. Enjoy.

New York City, September 21, 2016

★★★★ Light flashed into the apartment from balcony door glass across the way. A persistent film of high cloud left the light sharp but uncannily thin. By school pickup time the air had grown drier. The shade was soothing unto drowsiness. Audible splashes hit the sidewalk as a man used the three-walled shelter of half-booth pay phone as a urinal. A little girl kicked at a pigeon with real snap and intention. The thin layer of cloud grew thicker and softly banded, then developed fluffy glowing curls as yet another lush sunset spread under it. The five-year-old licked cake frosting off his shirt, then went after his presents bare-chested.

Instagram Is The New TV

A too-close look at Karlie Kloss’s new eBay ad

I’m human, so I look at Instagram every twenty minutes. Between all the friends and acquaintances and nail artists I follow, there are usually ads—this much I’ve gotten used to, though I was once shocked by it. But recently I’ve noted there are TONS of them, and from real brands, not just pixelated vitamin suppliers. There are ads for cheesy-looking new ABC shows, close-captioned Walmart sponsored video posts, and Delta ads that are also somehow Amex ads featuring Tegan and Sara. They’re coming hard and fast down the pike, especially now that the timeline isn’t even a goddamn timeline.

Yesterday, about a year into the inclusion of ads on the platform, Facebook’s Instagram (which, let’s just take a moment to recognize how odd that phrasing is—Instagram is literally a brand’s brand) announced that it’s sold ads to a half a million brands, so basically every third post you see is now an ad.

- Why You’re Seeing More Ads on Instagram

- Instagram Has Now Sold Ads to 500,000 Brands After a Huge 6-Month Run

However, I also follow Karlie Kloss and other celebrities (I’m human, remember), so I see a fair bit of #sponsored #ad content now and then. It’ll be something like Kim Kardashian with blue gummy bears in her hair or Chrissy Teigen with a Chase Sapphire card in her teeth. Today I was fed a full commercial from Karlie Kloss, which was amazing because it was just a fully produced video ad like the ones you used to see on television when you used to watch live television.

I am also captivated by the idea that eBay is now lowkey trying to be like, “Hey, we can do Amazon, remember us, we sell items and ship items! Many of the items on eBay are new, really, it’s not just for like re-selling your old jeans or stereo equipment. No seriously, haven’t you noticed that Amazon kind of became like eBay anyway at some point with the sellers and the ratings and stuff? Or was it the other way around? Please come back. We are a competitor. To Amazon.”

We all use Amazon all the time, except for those conscientious abstainers who are like, “nah too much cardboard” or “I only go to real stores” or “the drones don’t reach my estate.” And eBay knows that, and it wants some of our business back.

Another great thing about this ad is how the title card makes it look like a cool branding collab between Karlie and eBay, like Outdoor Voices x Glossier or Chance the Rapper x H&M x Kenzo; you know that because of the sans serif font and the x meaning cross like between but also cool:

There’s also a hashtag, because this is Instagram: #eBayUnboxed. Currently this hashtag hosts mostly duplicates of this video and stills from the same campaign, and a similar ad by celebrity interior designer Nate Berkus with much lower production value and a much sadder quote: “For some reason, people think of eBay as a place to find, like, dusty collectibles and I can’t figure out why.” Nate Berkus, you know exactly why. He goes on to say unenthusiastically that he finds the “best new things” for himself and his family and you guys should check it out. It’s very sad.

The ad reminds us that many items ship within three days and because Karlie is holding a green juice and wearing beige over-the-ear headphones atop her all-red athleisure outfit, many of these items are probably similarly cool because Karlie has cool, hip taste:

This next screen to me just screams, quietly, desperately, “Oh um also and a lot of items ship for free even though we don’t have a memorable moniker for it like ‘Prime’ but just trust us it’s the same, we’re a competitor.”

The saddest thing I think about this ad is the timestamp on Karlie’s iPhone:

The ad reminds you too that in addition to baking cookies, Karlie kodes, which is brand-adjacent to eBay, a tech company:

My main criticisms of this ad are: 1) Karlie very clearly says “I need to re-decorate,” though her apartment is clearly empty to begin with, and 2) it is very desperate and earnest on eBay’s part. Also Karlie will shill for anything (the same is ALMOST true of Kate Moss but the distinction is subtle: KM can sell anything; Karlie will). By the way, don’t bother Googling every item you see in the ad because I have already done that, and yes, you can buy Philippe Starck ghost chairs on eBay:

“Did we miss anything?” Karlie asks her newly decorated apartment. Yes: Seamless. Just keep scrolling:

White Noise

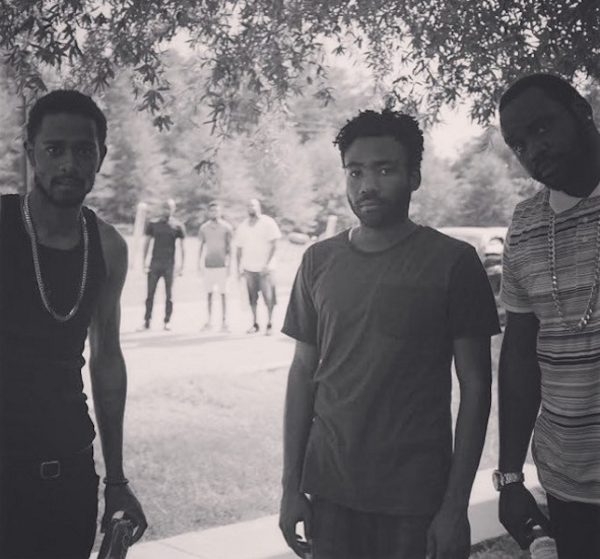

Donald Glover’s “Atlanta” depicts young black men with humanity.

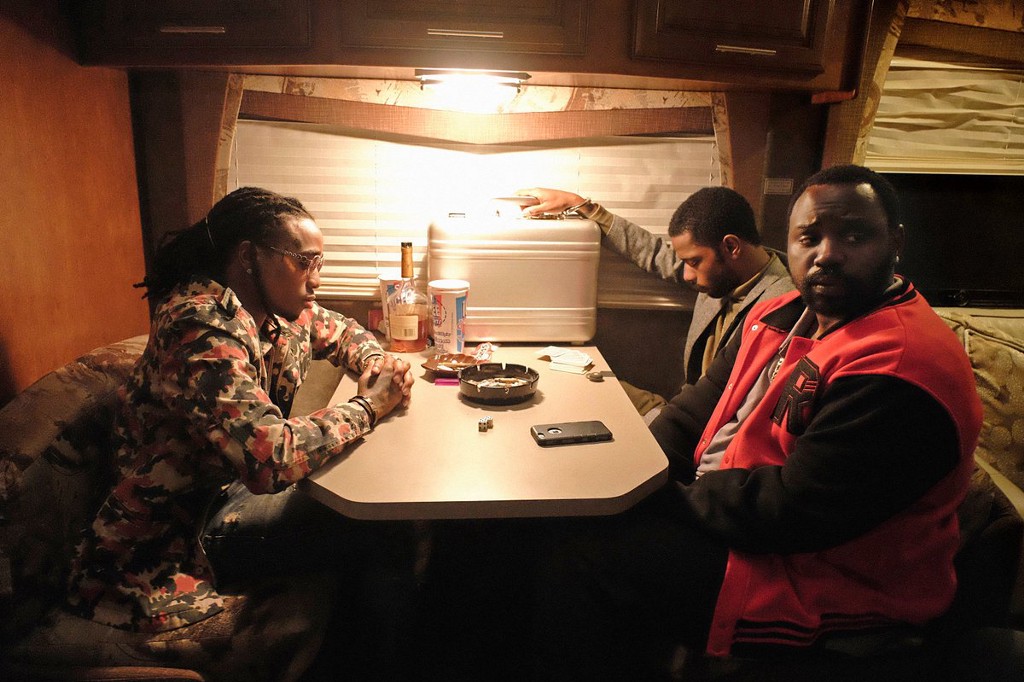

“Atlanta” is the blackest show on television. (This is not quite the same as saying that it has the greatest number of black people acting in it, or the most black people paying for it, or even the highest ratio of black-to-not-black writers — which, although probably true, isn’t what I’m getting at). The streets are black. The cinematography is black. The exchanges between characters are very, very black.

It is what Zadie Smith has called the “culturally black meaning” of the word soulful: “feeling transformed into something beautiful, creative, and self-renewing, and — as it reaches a pitch — ecstatic.” “Atlanta” is just black, and not simply for the sake of a bit. Its blackness isn’t maximized as a tool to shock its viewership, with warring record labels and absurdist between scene music videos, and it isn’t casually injected as a prop or a set piece, or an oh-by-the-way for polite evening sitcom viewerships, either.

Donald Glover conceived of the show in 2013, but he was busy: he rapped, he joked, he pulled a man off of Mars. He was on the verge of returning for the sixth season of “Community” before opting out to focus on “Atlanta.” When asked about the three-year gap, Glover merely responded, “That’s how long it takes.” And it shows.

“Atlanta” follows the misadventures of Earn, an accidental music producer, his cousin/client Alfred (aka Paper Boi), and Alfred’s partner, Darius. You could say they’re trying to break into the music business, but that would be lazy. Really, they’re navigating life in the city (although, curiously, I have yet to see a comparison between “Atlanta” and “How to Make It in America,” or even “Girls.”)

They stress over bills. They work shit jobs. They go to jail, and get out, and see themselves on the news. They treat their partners to overpriced dinners and immediately claim credit card theft. They get high on couches, and higher in cars, and highest simply walking from one end of the block to the other. They face vehement and total rejection from their parents, as Earn does in one of the most uncomfortable familial takedowns I’ve seen on television: In a katana-sharp brand of casual contempt black parents have wielded since time immemorial, Earn’s parents dismember relationship status, his joblessness, his lack of education, and digestive habits without even letting him past the porch.

Under Hiro Murai’s direction, all of it is beautiful, but none of it is flashy. There is a lived-in-feeling to each scene, as though these things have happened before, and they will happen again. This commitment to a Lack of Bang is at its most visceral in the first episode: after finagling Alfred’s first major block of radio-play, Earn finds him blasting the track in his car with Darius, both of them bopping deeply to the bass. When the two men finally acknowledge Earn, it’s to extend the joint in Alfred’s fingers and ask Earn if he’d like to partake. Another director may have maximized Earn’s first act of valor with fanfare, or mood music. But here, as in life, Earn thinks before he inhales. He smiles quietly at the invitation.

Critically, the series has done well. Typically unexcitable people are losing their minds. The Economist lauded the series’ “important new voice”, Jezebel deemed it “reliably special,” and the New York Times has called it an “idiosyncratic hangout.” Indie Wire anointed it as “essential viewing.” In the midst of these accolades, the series has just been renewed for a second season.

But it is one thing to account for the series’ reception, and another to try codifying what is actually is. The Daily Beast described “Atlanta” has been described as “primarily a show about hip-hop,” which is both true and not. Mother Jones called it a “take on the African-American experience,” which presupposes that African-Americans are identical, with uniform, indistinguishable experiences, more akin to Cheerios than individual people. But this series, and the entirety of conscientiously plotted network television shows with African-American leads, can be boiled down to this notion: it is the extension of an olive branch into previously uncharted territory. Glover is offering of a joint from a crowded car.

Atlanta may not have been the obvious choice for the setting — surely New Orleans or Philly or Houston could’ve pulled it off — but it is where Glover came up. The show’s specificity is evidence of his affection. It certainly isn’t Tyler Perry’s Atlanta, or TI’s Atlanta, or the Atlanta combusted by the city’s Real Housewives, but Glover’s city alludes to the fact that it contains all of those things, even if it isn’t any one of them in particular. Locals seem to agree with his depiction. But even if the city is cosmopolitan and multifaceted and capable of containing these multitudes, even that seems to be changing rapidly. Its blocks are becoming homogenized. And, as Glover claims, when justifying one character’s use of a highly localized patois, “that dude won’t be around in seven years”.

When black people are on television, it’s either very bad news (they’ve been executed for holding a book, or playing in the park, or reaching for identification) or very good news (they’ve won the presidency or some sort of championship). They are seldom extended the empathy that presupposes them as human beings just living their lives, as elementary school teachers, or dentists, or couples, or violinists, or firemen, or even detectives (with a few notable exceptions). This could largely be the result of a lack of imagination in our writers’ rooms. And that is largely the result of a lack of diversity in those same corners. In a discussion between Ava DuVernay and Q-Tip at last year’s Tribeca Film Festival (another thing lacking: two black people simply talking to each other onstage), DuVernay attributed the absence to a void in entertainment culture: “To say you’re a fan of black filmmakers is to say you’re a fan of two or three films…We don’t have a Woody Allen, or a Mike Nichols.

In a 2015 Rolling Stone interview, Chris Rock touched on the same impossibility:

If someone was going to hand me something like Top Five, I’d be more than happy to act in it…I’d rather work with Wes Anderson, but I don’t look like Owen Wilson. I’d love to work with Alexander Payne and Richard Linklater. But they don’t really do those movies with black people that much. So you gotta make your own. And the black movies of substance tend to be civil rights.

Recounting the production of her 2000 film, Love and Basketball, Gina Prince-Bythewood recalled her own struggle producing a film about black romance with two black people at the helm:

Every single studio turned it down. It was devastating. I remember I had a list on my fridge of all the studios and every day crossing another one off. And I kept getting the feedback that it was “too soft,” which I just didn’t know what that meant, how is it soft? But I think part of it was also it was a film with two people of color in the lead in a love story. It wasn’t a comedy. At that time, obviously there was the success of “Boyz in the Hood” and “Menace II Society” and this was something definitely different. But again, it was what I wanted to see and what I felt we hadn’t had an opportunity to see.

Unless they were cracking a joke or firing a gun, black people on film weren’t identifiable. They were invisible. But if there really is anything unheralded about “Atlanta,” it’s the series’ defiance of that notion — it depicts young black men with humanity. An already rocky date is tipped bassackwards by an overeager waiter, and a pair of young men is blessed at the local hot-wing diner by the jubilance of unexpected lemon-pepper flavored joints with the sauce. They experience the shame and awe when you’ve forgotten the key to your suitcase (filled with drug money) at the apartment, and the consequent relief when your supplier comes up with the workaround (cutting out the money, leaving you with the suitcase).

You could argue that these are too far outside the experience of most viewers to hit home. But they cannot be as far as the conquest of seven kingdoms by dragon-fire, or a subpar execution of the tango in a room of celebrities, or even the day-to-day interactions in an office beside a forever-present laugh-cam. It boils down to a simple, disturbing question: who on television gets to be human?

Glover hints at an answer in a recent interview with Vulture:

I just remember Chappelle’s Show, reading interviews, him being like, ‘We just wanted to make this personal.’ So just let me try and make this show as personal and possible, and not just all the nice and fun stuff of being black all the time.

He isn’t far off from Ralph Ellison, who wrote in an essay entitled “Twentieth-Century Fiction and the Black Mask of Humanity”:

Thus when the white American, holding up most twentieth-century fiction, says “This is American reality”, the Negro tends to answer (not at all concerned that Americans tend generally to fight against any but the most flattering depictions of their lives), “Perhaps, but you’ve left out this, and this, and this. And most of all, what you’d have the world accept as me isn’t even human.”

The first time I ever went to Atlanta, I was eleven or twelve, having been driven up for my cousin’s graduation. Her younger brother was charged with babysitting me, and he took the job gratefully, which is to say: he was paid, and I don’t remember him bitching or sneering or scheming to drop me off in a swamp.

I hadn’t really hung out with black males of a certain age before then; there weren’t just many in my pocket of suburbia. But my cousin was kind and accommodating, and he asked if I was hungry. After stopping for gas, he met a friend, and they exchanged a handshake unlike any I’d ever seen. His buddy joined us, slurring a “What’s good, bruh,” and proceeded to roll a crusting spliff. They passed it between them in the parking lot. An older white woman walked by. She frowned at the car, at us, at in our general vicinity. A young black dude cruised around shortly afterwards. He clapped his hands with my cousin. A gas station attendant, and an elderly black woman, and a gaggle of Latino kids pointed and laughed at the smoke, but whether this was amusing or alarming to my cousin was lost on me because by then they were deliciously above the clouds

They drove me through hilly Atlanta, from the nicer parts of Buckhead to what looked like less nice parts. Then they drove back. My cousin’s friend asked me if I enjoyed playing video games, and when I answered in the affirmative he nodded solemnly, admitting he had no console system. But he’d like to have one someday. Eventually, he’d have the money. We made it to the graduation ceremony a little late, and then we sat in the back.

I had never spent a day like this, did not know it was how people could act. For all of the Culture I’d consumed by that point, I’d have been more comfortable assisting Spiderman down a skyscraper, or diffusing a bomb on a crowded bus. Television and suburbia hadn’t prepared me, and it’d be minute before I had another just like it. “Atlanta” will, if nothing else, make these experiences less of an anomaly. Whether or not people agree to spend more time with Earn and Alfred and Darius is their own business — that’s their call. But maybe they’ll look at the black people in parked cars and across the sidewalk and in waiting booths and in parks just a little deeper. Maybe they’ll allow them a little interiority.

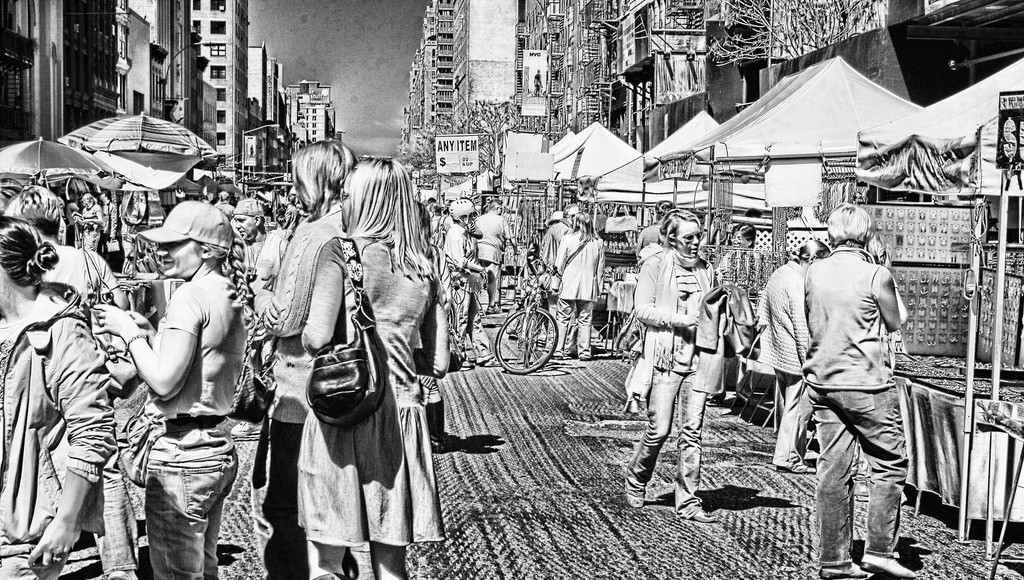

Street Fair Reform Will Bring The Change New York Needs

I mean, the other stuff is really hard to do, I guess.

So those of us who have feared that, instead of craftily allowing himself to appear as an amiable dunce in an attempt to do liberalism by stealth, New York City Mayor Bill de Blasio actually is just a big fucking dummy who means well but couldn’t tie his shoes without asking for four different perspectives on whether you put the left lace over the right or the other way around and then just tying them however the real estate industry tells him to, have had very little in the last three years to assuage those concerns. But wait, what’s this?

There’s more!

Okay, so it is not the change that I voted for, or even thought about, back in 2013, but given what’s been on offer I will take what I can get. Also, you know how everyone keeps saying the city’s center of gravity has shifted to Brooklyn? Let’s shift all the street fairs there from now on too, so we can justly acknowledge the borough’s primacy. It only seems fair. Enjoy your mozzarepas, Park Slope!

"Bad" Gilbert Is The Fedora Of Tennis

The sport needs more female commentators, and fewer bad hats and nicknames

Tennis matches can be very long, and for the uninitiated, rather confusing. Distinguishing the groundstrokes is difficult. The scoring belies mathematical logic. Most of the time, even the players appear baffled by the challenge system. In this sporting world, one wants a well-informed guide, or at least pleasant company for matches that can extend beyond four hours. Instead, there’s Brad Gilbert.

Throughout his long career, Gilbert has worn many hats (sorry): ESPN commentator, tennis coach, author, former world no. 4, a signature Raiders cap, a black Metallica bucket hat in the stands of all-white Wimbledon, and for the most recent US Open, an abundant collection of fedoras.

Tennis has always provided a welcoming home for the lover of funny hats. The visor of yore persists alongside headbands — neon, elastic, and those tied and retied by hand. The latter acts as salve for the neurotic tennis player performing the server’s sign of the cross: headband, necklace, hair tuck, towel. So it is perhaps unfair to harp on the minutiae of Gilbert’s headgear in a sport preoccupied with such strange fashion.

But Gilbert’s hats are not stylish; they’re a stunt. One designed to increase the visibility of Brad Gilbert. One suspects the Metallica bucket hat was worn less as the good luck charm for his player (as it was admitted to be), and more as a cloying attempt at quirkiness, intended to entice a frequent zoom from the Skycam. In a post-match interview, he once asked Roger Federer not about his match, but about Gilbert’s own attempt to sport a headband. “Not a good look,” said Federer:

The rules of hats are not sacred, but they do exist. And while the evolution of fashion necessitates the occasional disobedience, most of us would be well advised to play along. This rulebook is hardly stringent. Take your hat off indoors. Do not wear the same hat every day. The fedora is a dress hat, and while it can be paired with causal wear, Miss Manners advises caution. Gilbert breaks all of these rules. Indoors, outdoors, shirts collared or not — in the Gilbert wardrobe, fedoras pair with everything. (Even athletic wear.) The manic insistency of this uniform is deeply off-putting. As Dayna Tortorici reminded us, “Freddy Kruger, too, wore a fedora.”

One friend drew a comparison to the tailored zaniness of Craig Sager’s suits, noting that, even if Sager weren’t broadcasting from a basketball stadium, his wardrobe would remain largely unchanged, because he genuinely loves those suits. On the contrary, it’s harder to imagine Brad Gilbert sporting a Metallica bucket hat when there aren’t any cameras around.

Gilbert’s hats suggest a logic where anything done to excess increases visibility, a tendency toward overindulgence that also explains the nicknames he generates with stunning alacrity. Nicknames are not rare in sports, but they are typically reserved for stars — Big Papi, Flo Jo, The Final Five, Black Mamba — and usually, they are not generated all by one person. But Gilbert’s love of verbal associations is boundless. Take some familiars from this US Open. In Gilbert’s perplexing lexicon, the calm Simona Halep is “Halepeño.” Mild-mannered Stan Wawrinka, who won his third grand slam this month by waiting politely through Djokovic’s (the “Djoker”) questionable medical timeouts, is a “Stanimal.” The winner of this year’s US Open, the fully-grown adult woman Angelique Kerber, is the “Kerber Baby.” Andy Murray, whose squawking outbursts can appear vaguely avian, is surely not haggard enough to warrant “Muzzard” as a sobriquet.

Gilbert called Rafael Nadal “Ralph” until his fellow ESPN announcer, the always-elegant Chris Fowler, made him stop. When he suggested “Rotisserie Pouille” for Lucas Pouille, the Frenchman who ousted “Ralph” in the fourth round of the Open, Ivo Karlovic, the big-serving Croatian, responded over Twitter:

Rotisserie Pouille doesn’t make any sense cuz pronunciation is totally different then poullet (chicken). https://t.co/7Iuj2HtWP6

What do u think of change for Rotisserie Pouille to My name is Luca

To be clear, when “Rotisserie Pouille” received negative reactions, Gilbert’s response was to suggest an alternative: “My Name is Luca,” the title of a song about child abuse.

The problem with Gilbert’s nicknames, though, isn’t that they aren’t accurate or that no one else uses them, but that they aren’t funny. They’re one-sided attempts at inside jokes, designed to draw attention to the singular humor of Brad Gilbert.

To be fair, Gilbert does deserve some credit, just for different things. He coached grand slam winners Andre Agassi, Andy Roddick, and Andy Murray. He briefly coached Sam Querrey, but whether Sam didn’t rise in the ranks quickly enough or the sibilant consonants of his first name proved too difficult, their relationship fizzled.

The player-turned-broadcaster is familiar from many sports, as is the player turned coach. But tennis is the only sport I know of where individuals can hold both positions at once. Despite the glaring conflicts of interest, most navigate their dual role successfully. Darren Cahill (Simona Halep’s coach) and Patrick Mouratoglou (Serena Williams’ coach) are agile in their transitions, never serving as announcers for their own players’ matches and when asked to comment, appearing believable in their neutrality. After taking on Halep, Cahill went so far as to stop calling women’s matches altogether. Earlier this year, John McEnroe drew criticism for appearing in the booth during a match between Milos Raonic (whom he was consulting) and Federer, but even McEnroe, the most famous rude person in sports, acted with decorum when the pair split. Serving as both commentator and coach “ended up becoming an issue,” he said, adding, “I’d love to see all the guys play their best because I think it’s better for tennis.”

When Roddick and Murray each dropped Gilbert rather abruptly, he demonstrated none of this grace. On ESPN, shortly after his break with Roddick, he compared his former player’s match against Federer to a football game between Oklahoma and USC. The implication being that Federer (USC) humiliated Roddick (Oklahoma). Roddick responded, “There’s no question it’s a diss, but I’m not going to play that game.” As rehearsed with Roddick, so repeated with Murray. When asked about his breakup with the Brit, Gilbert sounds like a jilted lover praising what his ex has learned since the split: “We still speak. He is now doing a lot of things I was asking him to do.” First time farce. Second time, also farce.

Gilbert is best known as the coach for these players, because he talks about having coached them all the time. As a commentator, Gilbert draws frequent comparisons to Agassi’s return of service and Roddick’s serve. He speaks knowingly of the ins and outs of Murray’s game, a player he coached for only one year, nearly a decade ago. Grand slams bring together the top 256 players in tennis (give or take some wildcards), a group so diverse in talent that commentators should have plenty to talk about for two weeks of matches. But to hear Gilbert’s outsized emphasis on players he’s coached or consulted, you’d think the field comprised only his handful of players.

In the end, Gilbert’s antics recall a bit too strongly another place of fashion, nicknames, and resentment: the country club. To its credit, tennis has thoughtfully distanced itself from the monogrammed playground of its past, but Gilbert’s showy hats, epithets, and all-occasion fist bumps threaten to turn tennis back into the clubby world of insiders that tennis has worked hard to escape.

A less cranky person might ask, is the situation truly that dire? It’s only color commentary Gilbert’s providing anyway, and he is entertaining. (One twitter account parodies his grammatical errors and deep love of Bud Ice.) Call me a nicknameless grump, but Bad Gilbert bespeaks a larger issue for tennis commentary. After all, the country club is also deeply exclusionary to women.

Tennis’s attention to gender and wage equality has always been more progressive than most sports. In 1973, Billie Jean King founded the Women’s Tennis Association and weeks later, defeated Bobby Riggs in a “Battle of the Sexes” match. Later that year, the US Open became the first grand slam to offer equal prize money. It took thirty-four more years, but now all four slams provide equal pay to female and male players, and when Serena Williams is involved, women’s finals tend to sell out before men’s. But women still get less time on the court and in the booth. Women play best of three set matches, which means less time on television for the players and for the commentators, who are also (mostly) women.

In the early rounds of a grand slam, a pair of female commentators typically calls the women’s matches, but as the finals near — and the number of viewers increase — the announcing teams turn coed. In the most recent US Open, both female semi-finals were called by one man and one woman. The job of announcing the men’s semi-finals? Two men. For the finals, the depressing trend continued. One man and one woman called the women’s final while the men’s final was called by four men — three in the booth, and Gilbert in the stands.

In Sandy Harwitt’s book, The Greatest Jewish Tennis Players of All-Time, the chapter on Brad Gilbert is titled “The Chatterbox with Something Important to Say.” And his New York Times Magazine profile — “Brad Gilbert Talks a Great Game” — leads with the line, “Brad Gilbert won’t shut up.” Brad Gilbert certainly has things to say, but so do the other commentators.

During the recent US Open, female commentator Chris Evert had to interrupt Gilbert as well as John and Patrick McEnroe’s discussion of men’s matches to talk about the women who were currently playing on the court at that moment. “If the brothers McEnroe are finished” she cut in, her laughter forced and recognizable from any clubhouse.

It would be one thing if there were a dearth of talented, qualified female commentators. But Chris Evert has won eighteen grand slam singles titles. That’s eleven more than John McEnroe and eighteen more than Patrick McEnroe or Brad Gilbert. Pam Shriver, another ESPN commentator, holds twenty-one grand slam doubles titles. The McEnroe brothers combined have ten. Mary Joe Fernandez has two Olympic Gold medals.

Titles alone don’t create a good commentator, but consistency and exposure do. Chris Evert, Pam Shriver, and Mary Joe Fernandez are already strong announcers, but they only make up one third of ESPN’s analyst team. And it would be nice if an innocuous search for “female sports commentators” didn’t serve up links about the hottest women in sports journalism. These are institutional failures and not the fault of Gilbert alone, but defending his behavior as harmless color commentary renders the silencing of female commentators necessary for the sake of entertainment. Insisting that he quiet down, we all become killjoys, which is not quite a nickname, but one I’d happily take anyway.

Kelley Deane McKinney works at Cabinet Magazine and is currently taking tennis lessons.

patten, "Epsilon"

Don’t let the sunshine fool you.

Happy official Fall! It still feels like summer for now, but don’t worry, it will get colder over the weekend and also each evening it gets darker a bit before it did the previous day. You can tell because every night that moment where you have to rub your eyes and shake your head to block out all the thoughts and dread comes a little earlier. Can you imagine how horrible everything’s going to feel by November? Hold on to the light with both hands while you still have the chance.

Here’s a new video from glitch merchants patten. It’s about as good a preview for fall as I can imagine finding, so sit back and enjoy, because it’s coming for you.

So Is Writing A Job Or Not?

Writers have an answer.

Is writing a job? The Billfold’s Ester Bloom says no:

Kafka, Dickens, Nabokov — they all had day jobs. Novelists have day jobs! Roxane Gay, who is busy and accomplished enough to be several people, still has a day job. Writers have day jobs because being a writer isn’t a job. Writing is a thing you can do if you like it! It’s a thing you might get paid for, now and again, if you’re good at it! But it’s not a job.

Electric Lit’s Lincoln Michel says screw you, The Billfold’s Ester Bloom, it is too a job:

[S]omething can be a job even if it doesn’t pay you as much as you wish it would. Many literary writers today work as professors, editors, or book publicists while also earning income from writing. Many lucky authors who could live entirely off of their writing still work a part-time or even full-time job for extra money (because the Baby Boomers destroyed the global economy and shit is fucking tough out there). Still, earning 50% of your income teaching and 50% of your income freelance writing doesn’t mean that one or the other “isn’t a job” or is something you should approach with the attitude that you only “might get paid for, now and again.”

This is an important debate and yet it sidesteps an even more vital question: Why don’t we treat people who write with more derision and contempt, and also scorn and disdain? Why do we pretend that they are worthy of our respect or admiration? Why are we even spending time arguing about whether or not some jackoff with a burning desire for recognition and a thesaurus open in a nearby tab is performing notable labor? It is beyond dispute that writers are irritating sociopaths whose stunning levels of egotism are comically at odds with the repulsiveness they attempt to hide from the world under a mountain of verbiage. Even worse, their sincere conviction that what they do is not only necessary for the advancement of society but some sort of calling thrust upon them by a higher power manages to blend pretension and hilarity in quantities no one has quite managed since Madonna’s “Like a Prayer” video, although in writers it is genuinely offensive, as opposed to how Madonna did it.

There’s an old saying about writing

It’s horrible bullshit perpetrated on a disinterested public by people who believe their insights and feelings are somehow more precise and honest and worthy of attention than anyone else’s, and the self-indulgence is so grotesque that it makes acting, which at least involves some amount of physical labor, seem like a genuine and worthwhile profession. Also, the people who do it are by and large unattractive, and I don’t mean personality-wise, although let’s face it, they are as fuck-all ugly on the inside as they are on the outside. The astounding degree of self-regard it takes for someone to call himself a writer, let alone set out to put his idiot thoughts on paper with the expectation that they will be both read and welcomed is a better argument against Darwin’s theory of evolution that any Bible-thumping evangelist could ever dream of. Fuck writers. I mean, not literally, they are unfuckable. The only thing that they are worse at than sex is writing about sex. Let’s shun them altogether.

that, while perhaps a tad vehement in its expression, does not suffer from a lack of accuracy in its assessment. (You might not be surprised to learn that sources suggest this quote comes from Marilyn vos Savant, the smartest woman in the world.) So yes, maybe writing is a job. Maybe it isn’t. But shouldn’t we be spending more time on making the people who do it feel as bad about themselves as we feel when we are subject to what they do? I have to believe that this is where we should really be focusing our energies. Thank you for your support.

New York City, September 20, 2016

★ If the gray out the window looked no better than what had been outside the day before, the morning air was at least a bit less impenetrable. The sun gained control in late morning, but was uninterested in keeping it. The first step out of the restaurant with takeout lunch sent the eye skyward, looking for a threat in the renewed gloom there, yet a few yards away, sunshine was hitting the sidewalk. The afternoon light turned sinister and yellow, and the air lost whatever freshness it had briefly acquired. The sunset sky was striped and quilted, a glowing lovely surface almost as near and fully as irrelevant as a stage backdrop. What mattered was the dense, unpleasant night that followed.