"Cathy": 1976-2010

“Cathy” creator Cathy Guisewite is hanging up the acks after 34 years of trying to bring The Real Life Of A (Neurotic) Single Lady (Who Is Surrounded By Horrible People) to the funny pages. Guisewite, whose last “Cathy” strip will appear in newspapers on Oct. 3, cites the ticking of her “creative biological clock” (yes, she really said this) as part of the reason for her decision to move on, and Guisewite did show a bit of growth in recent years with jokes about digital bloat, and not just the kind you have after eating too many bon bons. But the strip’s already-slim roster of “reasons I will be alone forever and am therefore worthless” gags shrunk (a bit) after the titular heroine decided to marry her longtime on-again off-again sweetheart Irving. (Just like Moonlighting!) And that was in 2005! Surely Guisewite is cursing all the online-dating innovations her namesake missed out on by getting hitched back then.

To Everything There Is A Season

“An article on Wednesday about Tiger Woods’s golfing struggles heading into the P.G.A. Championship described incorrectly his change of heart about playing on the United States Ryder Cup team. His new willingness to be a captain’s pick for the team represents a 180-degree turn, not a 360-degree turn.”

Dear Sales Rep for a Textbook Distributor

Dear sales rep for a textbook distributor,

Sorry for lying to you on the phone.

This was in 1990-a full twenty years ago now. So I’m not sure you’ll remember. But maybe you will. I was a freshman at Connecticut College, which is located on a picturesque campus overlooking the Long Island Sound in New London, Connecticut. I had gotten a job at the school bookstore’s textbook annex, which was located not, unfortunately, in the nice old post-office building in central campus, where the regular bookstore that sold mugs and college sweatshirts and stuff was, but rather in the basement of Hamilton dormitory, one of six particularly unattractive buildings that had been built at the north end of campus in the 1960s.

The cement-brick walls in the annex were painted a dull yellow, and my boss, a woman named CJ who wore her gray hair in a thick single braid that reached almost down to her waist, liked to keep most of the lights off because the brightness of the fluorescent bulbs bothered her eyes. So it was dark, and, as you can imagine, pretty quiet: textbook stores see a week-long rush at the beginning of each semester, and again at the end, when students can return used copies for half their price back or something.

During the months between, though, most of my shifts passed without a single customer coming in. This was okay with me. CJ was pleasant company. She was around my mom’s age, and spoke slowly, and in extremely gentle tones, and not a lot. But she told me once that she loved New York City because on a visit there when she was younger, she noticed a spider web in a crack in the side of a building and when she looked closer, it was like she could see the whole world inside this tiny tableau: life flourishing in the most seemingly inhospitable environments. She’d play cassette tapes of whale songs on a box radio on her desk while she processed professors’ orders for upcoming syllabi and I took inventory or stacked or emptied shelves. It was kind of like the chill-out tent at a rave.

As the semester wore on, CJ started trusting me with different jobs. I learned to use the cash register, and would ring up the rare customer. I would write down the code numbers for books we needed and place orders with distributors, like the one you worked for. And sometimes CJ would leave me alone in the place when she had to go out for some reason. This was the case when you called.

It was late in the afternoon, and I was tired and bored and looking forward to meeting my friends at the dining hall after my shift. I don’t remember where CJ was. I was sitting by the cash register when the phone rang. You were calling to check on some order we’d made-make sure we’d gotten the code right, maybe there was a discrepancy with a past order or something. You told me the book and the code number. I knew about it, maybe I’d placed the order.

“Yeah, I think that’s it,” I said, probably sounding tired and bored.

“You wanna double check?” From the sound of your voice, you were older than I was. Thirty? Forty? You were a grown-up, a professional.

“Nah, I’m pretty sure that’s it,” I said. I was pretty sure.

You sounded a little annoyed. “All right. Maybe double check and call me back if there’s a problem. You wanna take down my number?”

I did not want to do that. I looked around the cash register; there was no pen. I looked over to CJ’s desk. There would be a pen there. But it was so far across the room, so unreachable from the chair that I was sitting. “Umm,” I said. “Okay.”

“Got a pen?” You said. I must have really sounded like an idiot.

Jesus! I resented your forcing me into an explicit lie. Still, I had already decided against getting up. “Yup.”

You told me your area code.

“Uhh huh.”

You said the next three numbers.

I remember I actually pantomimed writing them out, so as to the get the timing right. I’ve always been a shitty liar. “Uhhh huh. Go ahead.”

You read the last four numbers.

“Okay,” I said, “Got it,” already the pulling the receiver away from my ear to hang up.

“Wanna read that back to me?”

I hoped my gasp wasn’t audible. But it probably was. I didn’t know what to do. The thought of just hanging up occurred to me. But that probably would have just made the situation worse. We did need you to send us these books, after all. I giggled-a nervous, reaction to getting busted that had served me poorly many times in the past-and felt myself blushing, ridiculously, sitting there alone in a half-lit basement with whale songs playing.

“Ummm, yeah,” I said, hoping that you might laugh along with me, which you didn’t. “I didn’t actually get it all down. The whole thing. I don’t actually have a pen after all. If you’ll hold on a minute, I’ll get one.”

You weren’t surprised. You’d known all along. But your sigh was definitely audible.

Sorry about that.

The Dementia Bonus: Football as Black Servitude

My favorite contribution to the fake motivational poster meme is “Reinstated Slavery.” In deference to those who’ve not seen it, it depicts a white man — a coach, perhaps? — with his arm around the shoulder of a much younger black man, who’s got the netting from a basketball hoop draped loosely around his neck. The white man is smiling gleefully, his eyes on some wonderful prize off in the distance; the young black man is weeping. The caption reads, “Catch yourself a strong one.”

I don’t know much about sports, so I can’t tell you the name of the coach or the player or why they were behaving the way the were in that moment of time (though I imagine they’d won a championship of some sort). What I do know is that the poster succinctly sums up how I’ve come to look at football, boxing and, to a lesser extent, basketball, the older I’ve become: glorified servitude.

Where some see the Super Bowl, I see young black men risking their bodies, minds and futures for the joy and wealth of old white men. Anymore, I don’t just not watch sports; I dislike them in a very visceral way.

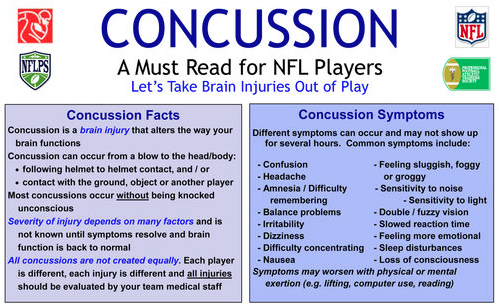

Recently a new poster debuted that now rivals “Reinstated Slavery” for my favorite commentary on modern professional athletics. This one wasn’t a joke. Starting immediately, a poster explaining the severity and symptoms of concussions will be hung in every NFL team’s locker room, probably in a place not easily seen, like an OSHA informational sheet. (It’s in part a project of the CDC, which is expanding its concussion and sports awareness program.)

“Concussion is a brain injury that alters the way your brain functions,” it says. “Concussions and conditions resulting from repeated brain injury can change your life and your family’s life forever.”

Life-changing injuries are what precipitated the poster in the first place. According to a study from last year, NFL players develop dementia and Alzheimer’s at a rate more than five times that of average Americans. The same study showed that “players ages 30 through 49 reported dementia-related diagnoses at a rate of 1.9 percent-19 times the national average of 0.1 percent….”

In others words, many professional football players — almost 70 percent of whom are black — are literally killing their brains, and that’s just the numbers on players in their 30s and 40s. For players over 50, it’s more than 1 in 20.

It’s shocking but actually perfectly sensible considering that football players slam each other into the ground at the end of almost every play. One would never guess it, though, from hearing NFL spokesperson Greg Aiello speak. “[T]here are thousands of retired players who do not have memory problems,” Aiello said when told about how many black men were ruining themselves to enrich him and his bosses. “Memory disorders affect many people who never played football or other sports.” For context here, think of a general sating a bereaved mother with, “There are many people who die of gunshot wounds who have never been to war.”

Lest you think it’s just the PR people who don’t care, the NFL’s legal team is indeed doing its part to contribute to the stonewalling:

On April 30, [2010,] an outside lawyer for the league, Lawrence L. Lamade, wrote a memo to the lead lawyer for the league’s and union’s joint disability plan, Douglas Ell, discrediting connections between football head trauma and cognitive decline. The letter, obtained by The New York Times, explained, “We can point to the current state of uncertainty in scientific and medical understanding” on the subject to deny players’ claims that their neurological impairments are related to football.

Exacerbating its unwillingness to accept that football can cause brain damage is that the NFL isn’t doing everything within its power to prevent head injuries in the first place. As recently as February, helmet-manufacturers were questioning the league’s helmet-testing program, worried that it was dangerously flawed. The tests proved so bad, in fact, that one manufacturer pulled out, with its CEO saying the NFL’s tests are “not deserving of credibility.”

For reasons that are obvious yet difficult to describe, the NFL’s policy of allowing its players to gradually destroy themselves would probably be less offensive were African Americans involved in ways other than just running, jumping and hitting. They aren’t. As of today, there are still no black majority owners in the NFL, and only one who comes close (Reggie Fowler owns 40 percent of the Minnesota Vikings). Out of 32, only six of the league’s head coaches are African American, a dearth that may be part of why blacks don’t even watch the NFL. According to an ABC study, less than 13 percent of the league’s viewership is black. Football fans are primarily white and relatively wealthy, earning $55,000 annually on average. 40 percent are over the age of 50. “Football has demographics that baseball would kill for,” said one CNN analyst, who, were he more direct, would have said, “White guys with hefty disposable incomes watch football.”

Maybe it’s a fair trade — black kids losing the ability to remember their mother’s name in exchange for a decade of big checks and fame amongst middle-aged white men. What’s not fair by any reasonable metric is what comes next, when players retire. Although the NFL recently started a fund that will give ex-players with dementia $50,000 a year for medical treatment, it’s also installed a byzantine bureaucracy between the patients and that money. Brent Boyd, a former Vikings lineman who now suffers from dizziness and chronic headaches, has been deemed ineligible for funds multiple times by league doctors, who say that one of his major on-field concussions “could not organically be responsible for all or even a major portion” of his symptoms.

Without the dementia bonus, the average NFL pension payments, which kick in at age 55, are hardly enough to cover a person’s living expenses and specialty medical care. As of 2006, a 10-year veteran who retired in 1998 would receive about $51,000 annually.

Boxing, which drops the niceties of football and lets minorities and poor whites pound each other’s heads sans helmets, sometimes until someone dies, has no nationwide pension plan at all. The assumption certainly being that all pugilists develop significant financial acumen while hitting the heavy bag for hours on end.

For a stark contrast, consider Major League Baseball, a sport that’s about 60 percent white and eight percent black. Bolstered by a strong player’s union, the MLB has a pension plan that dwarfs that of the NFL, despite the fact that most baseball players rarely hit the ball, let alone each other. Any player who gives just 43 days of service to the MLB is guaranteed $34,000 in pension benefits-just one day as a member of an active roster qualifies him for comprehensive medical coverage. Beyond that, a major-leaguer with at least 10 years under his belt is set to receive $100,000 per year at age 62.

Then there’s the NHL, a vastly, strikingly white organization. While the average NHL pension payment is about the same as the NFL’s, full benefits begin an entire decade earlier than they do for football players. What’s more, NHL veterans who play at least 400 games — about five seasons — are also recipients of a lump sum payout of around $250,000 when they reach 55.

Though the NHL and MLB take care of their players a little and a lot more than the NFL, respectively, both organizations make less in yearly revenues — the NHL about $4 billion less.

It’s all indefensible and disgusting and sad, but perhaps the sickest twist in America’s black-on-black violence as sport is how everyone reacts when our vaunted, dark-skinned gladiators explore bloodshed and aggression off the field, or outside of the ring. Vegas takes bets on when boxers will be knocked unconscious and football fans cheer when they think one man’s hit another hard enough to cause paralysis, yet it’s incomprehensible — inhuman, even — when Michael Vick makes dogs fight for his amusement when he’s not fighting for other people’s amusement. Imagine Mike Tyson’s surprise at how differently witnesses reacted when he wasn’t knocking a man’s teeth out in Madison Square Garden, but some $500-a-bottle nightclub in Manhattan. “You animal!” they must have screamed. “What makes you think it’s OK to punch someone?”

When I was growing up, I had a friend named Joey whose father, Rocco, was a beach ball of an Italian from northern New Jersey. Rocco was always tremendously affable whenever I saw him, being sure to ask me how my parents were and telling me I looked great, all in a charming, gravelly, thickly accented baritone. This warmth never surprised me until years later, when another friend told me that Rocco had a strange habit that emerged whenever he watched the NFL. When black players scored a touchdown and celebrated in the end zone, Rocco would shout at the television, as if he had Tourrette’s. “Do the nigger dance,” he’d yell. “Do the nigger dance.”

Cord Jefferson also writes at The Root.

The Rich Are Different: They Eat More Money

by Claire Zulkey

According to a recent issue of New York Magazine, local artisanal soda pop is the next hot food trend. This is going to make me look “in the know” here in Chicago because, while New York gets our weather remnants, we receive your stale food trends. Remember when cupcakes were all the rage back in the days when “Sex and the City” was a TV show? We just finally got over them (Chicago is one step ahead of food networks, though, as “DC Cupcakes” is now a thing). Currently our city is hot for hamburgers. If you’re a culinary trendster then you know the difference between M. Burger, DMK Burger Bar, Kuma’s Corner and Edzo’s. The whole macaron thing didn’t really take root here though, I think because the little cookies are too dainty for a city with tastes so bulky we like our pizzas to actually be pies at the same time.

Following food trends is secretly an upscale way of justifying eating things you probably shouldn’t. No, a hamburger or glass of pop or cupcake now and then won’t kill you, but the point of a craze isn’t moderation: if you’re really going to consider yourself up on the soda trend, you’ll know the difference and have opinions on Brooklyn Soda Works versus P&H; Soda versus Fort Defiance and so on right now. Get in on it while it’s hot: it’s fun, it’s old-timey! It’s not going to be fashionable for long so you need to get in there and try it and have your say. Being part of the communal tasting moment is part of the experience, but it’s a luscious bonus that the majority of the experience is eating something sugary, fatty and/or delicious. Eating indulgently somehow seems less sinful when it’s the thing to do. Eat a cupcake because you feel sad: that’s sad. Eat a cupcake because the gals on “Sex and the City” did it: well, now you’re living the life. That’s aspirational eating. It’s not so bad for you if you had to wait in line for it and pay a shit ton of money for it and do it in high heels.

There seem to be two issues at play these days when it comes to what makes foods “good” and “bad” (of course poor, innocent foods are not actually “good” and “bad” the way, say, the Holocaust was “bad” and eight hours of sleep is “good,” but you can’t deny that certain foods are more nutritionally valuable than others): calories and content. Take a Hostess Twinkie and then a “Twinkie” that is not actually a Twinkie but a dessert created by a trained pastry chef out of the finest ingredients in the kitchen of an exclusive restaurant to look like a Twinkie (this sounds like a great challenge for “Top Chef”). Many of us wouldn’t be caught dead eating a Twinkie: we’ve all been told that Twinkies never age because they’re made of wicked unnatural ingredients, Twinkies are filled with whale blubber, Twinkies will give you cancer. Yet you’d pay $12 for the honor of eating the “Twinkie,” even though they both may have the same amount of calories.

There’s a double standard when it comes to food that’s calorically bad for you. Hell, there’s a double standard even when it comes to food that’s good for you. Those of us who allegedly can afford it and “know better” aren’t supposed to eat baby carrots anymore: we’re supposed to go to the farmers’ market to purchase beautiful fresh-from-the-dirt carrots with green tops, or have them delivered to us in a weekly produce co-op box. You don’t cram them in your face to fill the void and grimly just take it because the food suits its purpose and is filled with these goddamn vitamins and nutrients-you thank Gaia for the soil and the sun that brought it to you and consider yourself one of the “good ones” next time you read a Michael Pollan article.

When it comes to people who live in urban “food deserts” though, we don’t expect that type of worship: they’re lucky to get frozen, even canned, produce. But junk food? That’s when we get snobbish. High-class cupcakes, local pop, hamburgers made by top chefs, these are little indulgences for foodies. But gas-station treats, Coke and Big Macs are part of the nation’s nutrition problem.

I emailed Dawn Jackson Blatner, a friend of mine who’s a registered dietitian (N.B. I am also an occasional client. I’m not immune to the struggles of “want to eat” versus “should eat”) to ask if she also thinks there’s a double standard when it comes to junk foods. She agrees, and invokes a phrase called ‘Health Halos’: “When ingredients are listed as organic, local, natural or artisan, people often don’t feel as guilty about eating the food and in fact feel that the perceived healthfulness somehow buffers the calories. There could be a slight health edge to the luxe version, though: one study found that our metabolism burns twice as many calories after eating the less processed versions of food. So, if we are comparing a cheap cupcake with more than 30 ingredients with a more homemade version with just 10 ingredients there may possibly be a slight difference in how our body reacts to eating each…but not enough to give homemade artisan cupcakes (or whatever trendy junk food) a dietitian’s stamp of healthy excellence.”

Of course, some people might not give a crap about a dietitian’s stamp of healthy excellence, especially if it’s 3 PM and they’ve had a terrible day. But even if we should be the last ones to cast aspersions on other people’s health, admit it, you’ve thought about “those people”, the people who don’t know better than to eat fast food three times a day, or can’t afford otherwise, who drink Coke instead of water and so on. They suffer, they’re part of the problem. If only they knew better, they could live better.

Head into a Starbucks any Sunday morning and you’re bound to see parents indulging their kids with mini scones or tiny boxes of organic chocolate milk. This is urban indulgence, and the biggest argument isn’t so much whether the kids should be having it but whether they’re making a racket that bothers everyone else who’s there on the WiFi they paid so much to use. However, head several neighborhoods over and parents are feeding their kids food that looks vaguely the same but costs much less and is made with less dear ingredients.

Paying more for a special, local treat isn’t just a caloric indulgence: you’re eating your privilege (and later flushing it down the toilet). If you meet two or more of the following key demographics when you eat trendy indulgences: thin, well-educated, white, financially sound-it’s okay, as long as you paid a lot for your food and know more about it than is probably necessary. If, on the other hand, you’re fat, poor, uneducated and perhaps not-so-white, put down the burger, because you’re part of this country’s nutrition problem. Unless, of course, you’re willing to come downtown and pay twice as much for it.

Claire Zulkey lives in Chicago. You can learn so much more about her here.

[Image via]

The iPhone's FaceTime: Too Soon!

Just as you suspected, no one feels comfortable using the new iPhone’s “Facetime” videophone thing… unless they really miss their cats.

The Pleasure of Ruins

Lately in my travels through the blogosphere, I’ve detected increasing unhappiness with the intrusive nature of what could be called our “brand economy.” As someone who identifies with this discontent, I was led to wonder if branding has actually grown more intense in recent years, or if by getting older-in the way one generation always complains about the next-I’m more impatient with the status quo of our more-or-less-in-theory capitalist system. After all, it’s hardly controversial to say that since the dawn of mass production, and perhaps even earlier, we’ve lived in a “brand-driven” society; it’s natural for companies to make products and advertise with the expectation that customers will recognize brands and be more inclined to buy new products by the same company.

It may be more controversial to say that the Internet has ushered in an era of unprecedented branding, and that this is driving our current fatigue. Allow me to make the case: in my experience, it’s impossible to go online and not to have a constant stream of corporate logos pass in front of your eyes, whether these belong to computer hardware or software companies, site owners, or the products we continually ignore (or not) in the sidebars and banner ads. (Related: the primary reason I’m not yet inclined to buy an “e-reader” is my fear of logos; when I read a book, I want my escape to be unsullied by a lurking symbol only inches away from the prose.) It may be that we are so oversaturated with brands and logos at this point that they have become meaningless, but I tend to think otherwise. Because the Internet is a boundless medium of transporting information-largely immune to traditional constraints of time (to the extent that digital content does not decay) and location-there’s a sense that brands associated primarily with the internet and its infrastructure are relatively eternal and more powerful than any dating from the pre-Internet era.

I remember living in Brooklyn after I graduated from college in 1990 and how one of my roommates became increasingly obsessed with a brand-free existence; he stripped the labels off cans of food in the kitchen, along with that of the dishwashing detergent, and even pulled off the marker on the refrigerator (he covered the hole with a handwritten quote by Richard Rorty); he threw away everything he owned with an identifiable corporate tag or mark and placed what remained into a small one-foot square cabinet he built into his closet, which held five white shirts he wore to work and an equal number of white t-shirts he wore when he was off. (The only books he kept were the old yellow editions of Walter Benjamin’s essays.) At the time, I was mostly amused or nonplussed by his behavior and privately did a lot of eye-rolling; I felt vindicated when at some point I picked up Generation X by Douglas Coupland and discovered that my roommate was effectively a caricature of the brand-haters so pithily described by Coupland, freaks who were far too serious about life and should really learn to relax. It wasn’t that I didn’t on some level share my roommate’s sensibility, but it seemed pointless to fight. Would it really make any difference for me to be so vigilant about scrubbing brands from my life? It seemed ridiculous. I was willing to spend five seconds peeling off the label of my deodorant (because it also looked oddly striking in generic plastic), but I wasn’t about to take an hour soaking a bottle of liquid detergent in hot water to unglue the label. (Although it did look pretty awesome in the end.) To cut brands out of your life struck me about as easy as processed sugar: what sounds good in theory is going to make you a miserable motherfucker.

I attribute this sense of futility to shaping larger discussions of “selling out” that were quite popular and heated in the early nineties, particularly in the context of music. What exactly did it mean for a band to “sign with a major”? Would they necessarily “blow” going forward? (All too often it seemed to be the case.) On the other hand, would you turn down six or seven figures for your next record? Unless your name is Ian MacKaye, I think not! Then Nirvana changed the equation, and ever since, to even mention “selling out” is generally regarded as cringe-inducing. Like politics or religion at a family dinner, it’s understood that maybe there’s something to discuss, but it’s so fucking boring and beside the point that nobody wants to hear it.

With the passage of time, I’ve become more sympathetic to my old roommate. (Not living with him helps.) One of the reasons I love gardening is that it’s generally a non-branded experience, at least superficially. When you stare at the leaves and flowers, you don’t (yet) see logos, even peripherally. Gardening (or camping or going to the park or the beach) is not without its flaws, however, in terms of an unadulterated brand-free experience. The problem is that it’s still very “active”; you essentially have to choose to create a non-branded environment for yourself, and-as every gardener or vacationer can attest-it’s a lot of work to get to the point where you can sit back and say, “ah, this is fucking sweet, I am at one with the natural world, and all you multinational corporations can go fuck yourselves.”

What takes much less work is to observe something like the subway panels of 163rd Street in Washington Heights, which offer a completely passive non-branded experience, outside of anyone’s power to create or refute. In the essential conduit of its time (by which I mean to compare the subway to the Internet) we see the graveyard of brands, a place where the once-envisioned posters and advertising have given way to derelict, ruined spaces, deemed without value by the corporations of our era. In the peeling paint and glue you can moreover find a kind of abstraction that resonates with art and creation (albeit a type of art without a creator). Here I’m consoled to a degree that extends far beyond what I find in the garden. When I’m suffocated by the relentless assault of brands, I turn to these panels and am reassured by the certainty that nothing is eternal, and here is your proof.

Matthew Gallaway is a writer who lives in Washington Heights. This is where you can learn about The Metropolis Case, his first novel

.

Here Is The Next Muslim Thing To Get Upset About

Today, the tiny clock on your wrist… tomorrow, the world: “For more than a century, a point on the top of a hill in south-east London has been recognised as the centre of world time and the official starting point of each new day. But now the supremacy of Greenwich Mean Time is being challenged by a gargantuan new clock being built in Mecca, by which the world’s 1.5 billion Muslims could soon be setting their watches.”

Mike Bloomberg: Still Awesome (For Now)

“I’m just telling you, I’ve always believed the government should not be involved in deciding who you pray to, what you say, or where you say it.”

-The wee billionaire from Boston is really on a roll these days. (And yes! People are apparently still talking about 9/11 Muslim Terror Mosque!)