Why Aren't You Watching "The Walking Dead" Anymore?

It’s important that you let everyone know where you stand.

Listen, if your job requires you to point to a television series that shows everything wrong with America today by all means go ahead and join the other take-providers on the Internet in offering up your angry, sorrowful explanation of why you can’t watch “The Walking Dead” anymore, but where are the pieces about “Talking Dead,” the show that airs immediately after it to discuss the program you spent the previous hour watching and reads out tweets that people — just like you — sent out on social media as the episode aired? I would make some comment about how this is the thing shows who the real zombies are, but real zombies hunger for brains, which is clearly not the sort of nourishment any of the viewers here crave. Okay, sorry, please get back to letting us know how difficult it is for you to continue with the empty cruelty of “The Walking Dead,” particularly when you compare it with something as powerful and socially significant as all the rape scenes on the dragon incest show. This is a golden age of something, alright.

I Blew a Kiss to the Cherry

On the Philosophical Biology of Marietta Pallis (1882–1963).

I came across Marietta Pallis because I’ve been researching a medievalist called Hope Emily Allen. In the 1930s, Allen identified an important medieval text written by a woman named Margery Kempe; I’ve long wanted to write a book about that discovery. For a time, Marietta and Hope lived together at 116 Cheyne Row, an extremely nice house right on the bank of the River Thames, in Chelsea. The historian Joan Wake (who called Pallis an “erratic genius”) lived nearby on Cheyne Walk, and there was a boarding house for women students down the street. It was a colony of a sort, a little enclave of woman thinkers. I went to stand on their street corner in August, but I couldn’t hear them whispering on the winds of time or anything.

Pallis wrote a poem to Allen, and it went like this:

I blew a kiss to the cherry

and the wind blew its petals to me:

with its delicate flakes I was whitened,

I loved, and the month was May.

Here, Pallis uses a sort of lyrical invocation common in medieval literature, launching into her theme through the language of flowers and springtime. It seems written so specifically for Allen, the talented medievalist. Lovingly designed, perhaps.

Scholars cite this poem when they want to back up the popular theory that Allen was queer, since just observing that she never married a man doesn’t seem quite sufficient. It’s not an outlandish theory, and it’s not an inappropriate piece of evidence. (Although it would be a good historical prank to be a gay poet and write a love letter to your straight friend.)

The book I want to write is a double biography of Allen and Kempe, but it relies on a historical triangle drawn between those two women and myself. If the line in that triangle which links me to Hope could include a common sexuality, all the better. My own advisor, godmother of queer medieval studies, has already written a little about her in these terms. The topic is good, and the field is ready. But if I’m serious about this book and I want to make Hope’s queerness a theme, I thought, I should probably be sure.

So, I went after Marietta Pallis. I read her poem like a piece of forensic evidence, hoping to find some kind of lesbian fingerprint that would crack the case wide open. But the “case,” as so often happens, turned out to be bigger than I expected. The deeper I went into Pallis’s life, the more her mystery expanded.

Alongside a woman named Phillis Clark (née Phillis Ursula Riddle, separated wife of Andrew Clark, often misspelled “Phyllis”), Pallis is buried on the central island of the Double Headed Eagle Pool (pictured above.)

The pool is in the shape of Greek Orthodox crosses, an Imperial Crown, Pallis’ own initials, and a double-headed eagle; it can only be seen from the air. Pallis had it dug in 1953 on the land she owned at Long Gores, Hickling on the Norfolk Broads for the five hundredth anniversary of the fall of Byzantium. She designed the pool herself, and had it cut from the peat using traditional Norfolk techniques. Pallis loved to swim and often swam naked in her pool — a practice described by the Journal of Historical Geography as a “gentle private bohemianism.” She died in 1963, at the age of 80, whereupon she took up permanent residence in the earth at its middle.

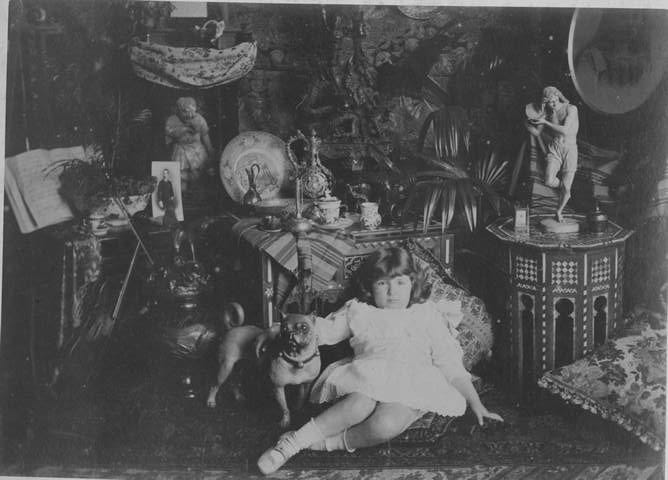

Pallis was born in 1882, in Bombay. Her father was a Greek poet named Alexandros, who caused riots in 1901 Athens by translating the New Testament into Modern Greek (eight people died; the translation only became legal in Greece in 1924). Her mother was named Julia Ralli. They moved to England in 1892, settling in 1894 in Liverpool. Pallis grew up loving landscapes, and she became a talented ecologist, a botanical painter, and a woman who wrote romantic poems to other women.

Pallis studied at the University of Liverpool, where she investigated the Dee estuary flora, and then worked on natural sciences at Newnham College, Cambridge. In 1911, she published two articles in esteemed scholarly journals: ‘Salinity in the Norfolk broads,’ and ‘The river-valleys of east Norfolk: their aquatic and fen formations.’

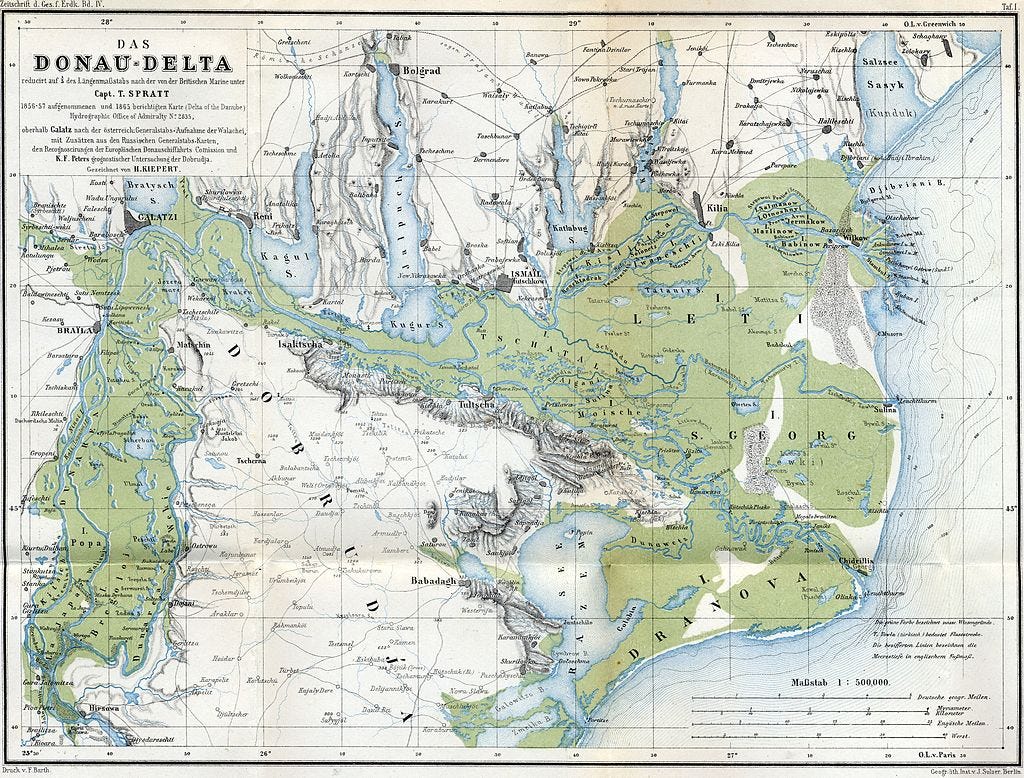

Pallis traveled to the Danube delta in 1912–13 to research a type of plant called plav. Her paper on plav was published in the Journal of the Linnaean Society: Botany (July 1916), titled ‘The structure and history of plav: the floating fen of the delta of the Danube.’ Pallis became interested in philosophical biology, exploring vitalism — the theory that there is some indescribable life-force animating all species.

A history of Norfolk peat-digging records that Pallis was a serious enough botanist to have had a couple of plants named after her: “a variety of Dog Violet, local to the dunes between Waxham and Sea Palling, was once known as Miss Pallis’s violet.” A hairy-leafed ash species that Pallis collected in the Danube is named for her, too: the Fraxinus Pallisiae. One of these trees is planted at her grave.

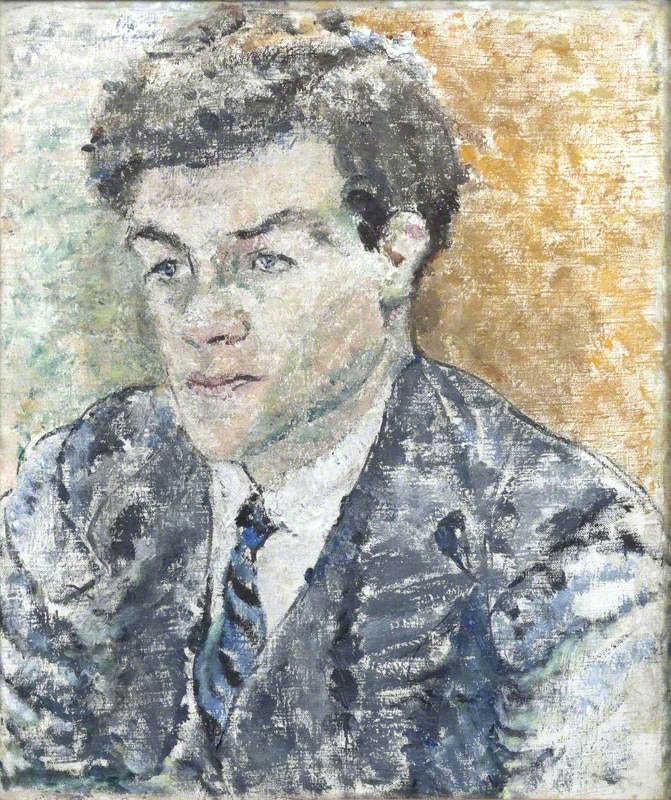

Pallis was a scientist, but she led an artistic life. She veered into cultural history, writing a book called Tableaux in Greek History (1952) condemning modernity and celebrating Orthodox Christian Byzantium. The Dictionary of National Biography notes that her “theocratic maverick conservative social philosophy was expressed through a bizarrely alliterative prose.” Pallis also took up painting alongside her botany studies. She had a solo show in 1938 at the Bloomsbury Gallery, but she never became a success. Her paintings are rather nice, in a squishy post-Impressionist way.

I fell into Pallis’s life like a swimmer. I came across a trove of photographs on the internet, and wrote to the email address on the webpage. I got in touch with Caroline Shelton, Pallis’s grandniece and goddaughter. In Bobst Library, there was a copy of a book called Sacred Gardens and Landscapes: Ritual and Agency. It was full of photographs of Pallis, as well as a painting she made of Allen that I’d no idea existed.

But by now, Allen had drifted toward the back of my mind. The motivating energy driving my research into Pallis had been my desire to know whether or not she had a romantic relationship with Allen. I knew that Pallis was buried with a woman, and this seemed, by parallel, to legitimize my speculation.

But that speculation had come to feel corrosive. It reduced Pallis to a clumsy cipher for queerness poised around the edge of another woman’s life, a life which I in turn wanted to bend to fit certain specifications. And all I was going on was one poem. Is that enough to turn a woman into a symbol?

Pallis’s goddaughter Caroline told me that she and her siblings think “partner” is too specific a word for Phillis. “Friend in middle and later life,” she thought better. Another relation, Dominic Vlasto, agreed, saying,“As far as I know, neither Phillis nor Hope was ever Marietta’s ‘partner’ in the sense people assume today.”

The happy couple buried in the marsh is too simple a vision. The past never quite matches the story that drew it to you in the first place, and historians can be clumsy. Past versions of society have shielded the sexuality of the dead from our gaze, and that is that.

Pallis broke away from Allen and Kempe in the queer constellation I had tentatively assembled. She became her own planet. And as soon as I began to try to see her for who she was, not what she was, I stopped.

Pallis and Allen have become imaginary companions to me, but they were real people, women who lived just beyond the horizon of our time. Writing about them and using the word queer is an act of reclamation, and it is an assertion of the value of queerness in the face of big silences. But the silence I have been trying to shatter is the loneliness of subjectivity in time — a loneliness I wanted to lessen by conjuring them up as friends and allies in the lifelong work of being academics.

There is exactly one book about Pallis, by W. T. Stearn. I am not going to write another. Maybe I am not going to write any books at all. Stearn notes that “Neither Greece nor Britain noted the passing of this colourful strongly individualistic forceful woman.” After Pallis died, her pool became overgrown. It was cleared again in the early eighties, though, and now anybody flying over Norfolk can catch a glimpse of this piece of art, the resting place of Marietta Pallis and Phillis Clark.

You can see films of sailing boats, farming, and a livestock market made by Pallis via the East Anglian Film Archive.

Josephine Livingstone is a writer and academic.

Three Things To Read

Having a hard time getting started today? Me too. Here are a few diversions.

The attention-merchant business model is in constant need of growth, and the way it has grown historically is either to find new times and space where we’re not occupied or to more subtly exploit the time that is already there. That suggests that all the periods you now regard as refuges or escapes from your crazy life will inevitably become targeted, because that’s where the growth activities are. For example, there has been a move to bring more ads to national parks, inside public schools, and into other sanctuaries that were previously walled off. As people are harder to reach, the efforts to advertise to them became more disguised, more intrusive, and more manipulative.

— “Does Advertising Ruin Everything?”

Pop art revels in, is excited by and transfigures the throwaway. It grew out of the newly opened sensibilities of its artists to the pop detritus of the everyday, the culture of multiple replication of images, of movie and music icons, advertising, comics, magazines, cigarette packets, beermats, trash — a manifestation of what Boty herself called “nostalgia for NOW”: “It’s almost like painting mythology,” she said, “a present-day mythology — film stars, etc … the 20th-century gods and goddesses. People need them, and the myths that surround them, because their own lives are enriched by them. Pop art colours those myths.” But we’re lucky, 50 years on, to still have anything of Boty’s work.

— “Ali Smith on the prime of pop artist Pauline Boty”

Whereas the rough edges of his younger, nasal reediness suggested chic bohemian nonchalance, now his low caroling is edged in defiance, and Darker’s production is singularly complementary to it. When he imagines, not so subtly, the stars above him losing light (“If I Didn’t Have Your Love”), his intoning dips below cherubic organs, hinting at what these enamored lyrics soon reveal — that this bright devotional is of the spiritual sort, hewing closer to his past career as a monk than as an Olympic-level ladies’ man. (The most jarring thing about Darker is how utterly devoid of lust it is.)

(That Leonard Cohen album is very very good, by the way. It’s the best thing he’s done since Ten New Songs. If it weren’t such a cold and broken Monday I’d feel a listicle coming on, but instead I will just say it would be six or seven for sure. Okay, this should hold you for a while.)

Mr. Neutral

The Adventures of Liana Finck

Liana Finck’s cartoons appear regularly in The New Yorker. Her book is A Bintel Brief. This cartoon strip is a spin-off of her Instagram feed, @lianafinck.

Diego, "Crack"

Let’s limp to the finish line together.

Two weeks from now I will be reminding you that there is only one more day of this nonsense, so if that somehow helps you get through today you should cling to it like a drowning man does a wisp of straw. I know, I know, it doesn’t help. I’m sorry. Hey, how about music? Here is something great from Diego Herrera, who, as Suzanne Kraft, put out my favorite album from last year. Enjoy. And remember, two weeks and a day. You can do it.

New York City, October 20, 2016

★★ A sudden chilly wind came down Amsterdam from Broadway. The leaves were rich gold but the sun was colorless behind thin clouds. That pallid showing was the most the sun would do all day. Through morning, the clouds thickened to a softly striped white, then on to a lumpy gray; the afternoon sunk steadily into darkness. An ominous drizzle began falling when it was time to hurry the children to and from the store to buy dinner. The apartment was too humid and opening the windows made no difference, but the air conditioner was too grimly cold to keep running.

The Internet Was Down Today

That’s why you didn’t hate yourself as much as usual

The Internet was down today and everyone was mad

Well, that’s the way we were at first, but then the thought was had

That maybe things weren’t terrible without those links to click

We didn’t spend the afternoon upset and feeling sick

We weren’t weirdly angry and we didn’t need to cry

We realized that hours passed without wanting to die

We somehow all felt better with no Internet around

So hear me out: This Monday let’s all burn it to the ground

Let’s gather round the servers and let’s stab them with some knives

Let’s kill the fucking Internet and get on with our lives

We’ll finally all be happy and we’ll finally all be free!

Please join me on my Internet extermination spree

If we can kill the Internet and make life sweet and fair

Wait, what’d you say, it’s up again? Eh, fuck it: Like and share.

Thank God I'm Not A Man

The Adventures of Liana Finck

Liana Finck’s cartoons appear regularly in The New Yorker. Her book is A Bintel Brief. This cartoon strip is a spin-off of her Instagram feed, @lianafinck.

Two Divorce Lawyers Watch "Divorce": Ep. 2

What the show gets right and wrong about divorce in New York

by Marcy Katz and Tom Kretchmar

“Best interests of the children” — the child custody principle we introduced in last week’s discussion of the “Divorce” series premiere — is supposed to be sacrosanct, and something everyone involved in a divorce seeks to promote. In reality as well as the second episode of “Divorce,” the concept is often perverted by one parent (in this case, Robert) as a cover for selfish or vengeful behavior. In the same way many people think prefacing a comment with “no offense” allows them to deliver insult without consequence, parents in custody battles often think that so long as they invoke “best interests,” they have carte blanche to do whatever they want, no matter how detrimental and awful it may be.

For example, if one parent has primary custody of the children during the pendency of a divorce, you might find him or her over-enrolling the children in extracurricular activities, under the guise of keeping the children optimally enriched, with the goal of deliberately impacting the time slots when the other spouse would otherwise have visitation time. Children aren’t necessarily optimally enriched by hyper-abundant extracurricular activities when it’s at the expense of their relationship with the noncustodial parent.

Robert engaged in a vengeful perversion of best interests twice in the second episode; both instances were borderline cartoonish. First, Robert uses the best interests of the children as an excuse for taking Frances’s clearing-of-the-air conversation outside of their house, and thus out of the children’s earshot, only to lock the front door behind her and then, through the door, clamor at her about her affair with Julian while the children puttered around somewhere behind him. An almost equally farcical weaponizing of “best interests” occurs when Robert tells Frances he’s going to pick the children up at school and unilaterally disclose the circumstances of the divorce (including Frances’s infidelity), since that would be “better than them hearing it on the street.” This results in a literal race between Robert and Frances to get to the school first. Notably, Frances isn’t racing for a chance to tell her side of the story, but to stop Robert from telling them anything altogether.

Robert’s haphazard lip service to best interests continues when Frances tries once again to clear the air with him. After Frances pleads that she doesn’t want to break up the family, Robert spontaneously exhorts, “This has been very alarming for the children.” Shortly thereafter, in the middle of a back and forth about their workdays, Robert interrupts Frances with a non-sequitur about not using the children as pawns, claiming the most important thing is to “think of the children first” and not put them “through any ugliness or chaos.” What’s really bothering him is his belief that Frances had bought the children a dog to make them like her more, undermining his alienation campaign against her. (The dog had in fact entered the picture because Frances’s friend Diane asked her to take care of it.)

As ridiculous as Robert’s conduct has been, none of it is really poisonous enough (yet) to have any real impact on the forthcoming divorce proceedings. To move that needle with shenanigans like these, Robert’s specific acts would have to have had a greater actual impact. But his actions and words may give us some insight into where his head’s at. He seems to have done enough homework about the mechanics of the divorce process to be motivated to convince the world that he is better suited than his wife to prioritize the children’s best interests. But does he really understand what that really means? We know from Robert’s cursory Google search of Julian at the end of the episode (“Julian Professor Columbia Granola”) that he’s lightly Internet-proficient, and at one point in the episode, he tells Frances that he is “well aware of his rights.” He may lack the discipline (or character) to commit to the course of conduct he really should be pursuing, but it seems he’s at least figured out that he’s supposed to be laying a foundation for a legal case that he’s the better parent.

Episode two also offers our first glimpse into Robert and Frances’s financial story. We find out that Frances is looking to open an art gallery on the local Main Street (in what appears to be Hastings-on-Hudson). Frances tells the real estate broker who’s helping her find a gallery space that she’s “waiting for Robert’s business to pick up” before she signs any lease, which gives us our first hint that Robert’s construction company is not doing well. With what little information we have about Robert and Frances’s finances so far, we have fewer inferences to draw than we do questions to ask: who, of the two of them, has historically had the higher income? Who’s earning more right now? Are they each business owners? If so, do they own their businesses outright, or do they have partners? When did they start their businesses — before the marriage, or during the marriage? These questions, and many others, will all have an impact on how their businesses and other assets ultimately get apportioned and distributed, and will also impact any spousal support and child support that gets awarded in their divorce.

In New York divorce law, the apportionment of “marital property” — i.e., property that the parties accumulate during their marriage — is referred to as “equitable distribution.” (We will undoubtedly have the opportunity to discuss the distinction between “marital property” and its counterpart, “separate property,” in future writing. The basic distinction is that “separate property” is not subject to division by equitable distribution. Generally speaking this primarily includes inheritances and all property owned by a party prior to the marriage, so long as it is not “commingled” with marital property during the course of the marriage. Commingling is another complicated topic we’ll get to.) Equitable distribution does not mean equal distribution; marital property is not automatically split down the middle and distributed half and half. Instead, New York law provides a laundry list of specific factors that may be accounted for in order to determine the equitable (i.e., fair) distribution of marital property in a given case, including, notably:

- The income and property of each spouse at the time of the marriage, and at the outset of the divorce;

- The length of the marriage and the age and health of both spouses;

- If there are minor children, the need of the spouse who has custody of the children to live in the marital residence and to use or own its contents;

- Any spousal support that will be awarded;

- The probable future financial circumstances of each spouse;

- The impossibility or difficulty of determining the value of certain assets, like interests in a business, and whether one spouse should be awarded the business in its entirety so it can be run without interference by the other spouse;

- Whether either spouse has squandered or secreted away any marital property while the divorce was ongoing.

Even after considering these and other factors, New York law specifically entitles a court to take into account any other factor it deems relevant in arriving at an equitable distribution of the marital property. The truth is that even though lots of technical analysis goes into the negotiation or litigation of equitable distribution (including substantial use of appraisers and forensic accountants, where applicable), there’s no set formula and no mandatory roadmap that a court must follow when distributing marital property. Accordingly, there’s no true way to predict what conclusion a court will reach in making its equitable distribution determination. As a result, divorce lawyers work as hard and as collaboratively as circumstances allow to achieve a resolution by negotiated settlement rather than through litigation. The hope is that both sides can, through collective experience and knowledge of the law, arrive at a result that both identify as being fair and within the boundaries of how things should ordinarily be expected to shake out after litigation, without having to have their clients suffer the expense and the gamble of leaving it entirely up to a court to decide.

Marcy Katz and Tom Kretchmar are New York divorce lawyers. They work at Chemtob, Moss & Forman, LLP, a matrimonial law firm based in midtown Manhattan.

West Street, Brooklyn

You were having a terrible time when I saw you — stumbling down the street wailing and sobbing uncontrollably, and it was in this state that you came upon a line of your peers. They were all wearing emerald green tabards that reached their knees, and clutching each other’s hands on the corner of West and Java. You didn’t notice them at first, what with the bawling, but they noticed you. In Britain it’s called a “crocodile,” a line of pairs like this, but as they shuffled to a stop and formed a close crowd, it was more tortoise than anything. They became, in their little huddle, quite stupefied by you, small mouths open as they witnessed one of their own. There were so many of them, none crying, and there was just one of you, deranged and inconsolable. But I wondered, in fact, if they might envy you. Because you had the luxury of being with your mother, just you and her and all her attention, while here they were, a muted crowd corralled by two not-nice seeming teachers. One of whom snapped, “Are you the teacher?” at a boy who’d made a suggestion and then, catching me looking at her, made a craven sort of grin, seeking complicity, or forgiveness.

The worst thing, I think, about being your age, is that no one takes your anguish seriously. That they assume the size of your feelings corresponds to the size of you, when in fact, your grief was at least six feet tall. Quite an ignominy, then, to have your mom smile ruefully at two other two fractious women shepherding the crocodile across the road, as if there was something ridiculous about you and your distress. There wasn’t, but I also knew, as I watched your mother drag you away, that in an hour or less you’d have forgotten it.