Nevada's Total Voters Today: Maybe 7 Percent of the State's Population?

Turnout looks to be still “good” in Nevada, but perhaps lower than predictions, which were for 190,000 voters at polls today in Clark County, says the county’s registrar of voters. (Clark County has 2 million residents, and the state has 2.6 million residents in total. For your reference, there are between 800,000 and 900,000 registered party voters in the state, and early voting accounted for about 310,000 voters.)

Bears Climb Tree

It’s a family of bears! In a tree! In Florida! Hell, just be happy it’s not more politics. Sometimes you just need to sit back and enjoy the bears, right? Bears!

RELATED: Check out this no joke AMAZING picture of a bear chasing a bison.

Today In Stupid Things

If there is indeed an end of the Internet, this very well may be it: “Prostitutes are not just coke-addicted sex workers. They are (often) very talented marketers and entrepreneurs. Here’s how to market your brand like a prostitute.” I know, right?

Grossout Sandwich Underachieves

“The Philly Taco” is a cheesesteak wrapped up in a slice of pizza. Apparently America has now gotten so fat and lazy that we’re not even making an effort to come up with decent gimmicky calorie bombs anymore. Maybe our greatest days really are behind us. Along with our gigantic asses.

The Mainstream Media and the Fight Against Communists and Social Security, 1936 Edition

“On the flat, in the crowd, half blind with dust, we look back with envy to those happier warriors, whose battle is won and whose achievements wear so serene an air of accomplishment that we can scarcely refrain from whispering that the fight was not so fierce for them as for us.” — Virginia Woolf, “Modern Fiction,” collected in The Common Reader, 1925.

Molly Dewson was very sad in the spring of 1934 because of the politics, so she wrote a letter to her friend Eleanor Roosevelt. Dewson was the head of the women’s division of the DNC, and she was in a tizz because Congress was evidently so opposed to Roosevelt’s policies. You will recall that Roosevelt took office in January of 1933, so this was something over a year into his first term.

Eleanor wrote back:

The ups and downs in peoples’ feelings particularly on the liberal side, are an old, old story. The liberals always get discouraged when they do not see the measures they are interested in go through immediately … Franklin says, for Heaven’s sake, all you Democratic leaders calm down and feel sure of ultimate success. It will do a lot in satisfying other people.

(That from from Susan Ware, Partner and I: Molly Dewson, Feminism, and New Deal Politics, 1987.)

Molly Dewson, let it be known, was no kind of wimp. She was a powerfully effective organizer, instrumental in the enactment of the first statewide minimum-wage law, in Massachusetts; she fought like a tiger to get women into high political office, including the first woman Cabinet member, Labor Secretary Frances Perkins; she was a driving force in Democratic electoral politics and in the fight for equality. Plus she was gay, and seems to have had an awesomely happy lifelong relationship with Polly Porter; they were together for fifty-two years. In the 1930s this maybe represented even more of a triumph of love and fortitude than it does now, which is saying something.

So miserable and pissed off about the politics, in the mid-1930s! And why not, when it was taking forever to get (for example) even a watered-down version of Social Security passed, owing partly to the efforts of the lunatic Dr. Francis Townsend and his competing “Townsend Plan,” and partly to those of “have-mores” like Robert A. Taft, Jr., son of the former president, who said that Roosevelt was willing to “mislead the people” and worse yet, “encourage them to believe that the government owes them a living whether they work or not.”

No really. If it weren’t for the telltale old-fashioned typesetting you’d have to keep checking the date to make sure it wasn’t yesterday’s blasted paper.

Even the watered-down version of the Social Security Act would not be passed until August of 1935, well over two years after Roosevelt took office. The NAACP observed that the original bill was “a sieve with holes just big enough for the majority of Negroes to fall through.” This “sieve” was devised, some have said, in order to ensure passage by courting the votes of Southern members of Congress — not by forbidding Social Security benefits to black Americans explicitly, but by excluding the types of jobs they ordinarily held from eligibility: agricultural work, factory work and casual labor.

So there were years of legislative and legal hurdles ahead before the system would work more or less fairly. These the administration quietly began to clear, one by one, fighting legal challenges and expanding coverage to include more and more classes of work. The first monthly Social Security retirement check was not disbursed until January 1940, and it was 1950 before the system looked something like the one we have now.

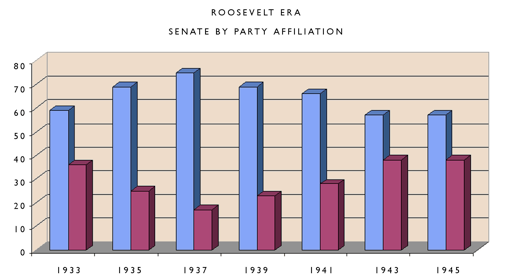

But wait, you say. Roosevelt enjoyed a congressional supermajority! Well, yes… in 1933, Roosevelt had fifty-nine Democrats in the Senate, and by 1935 that number had swelled to sixty-nine, sixty of whom voted for passage of Social Security; there was one vote against and eight abstentions on the Democratic side. In those days, the Republican party was not what it is now. Sixteen Republican senators and eighty-one Republican representatives voted for passage of Social Security, the Democratic President’s signature program. Imagine that.

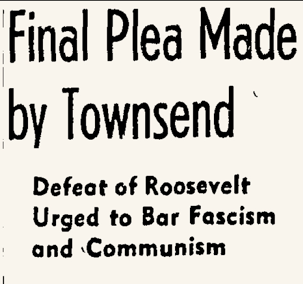

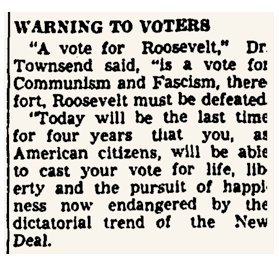

Republicans Attempt to Stem the Communist Fascist Free-Spending Totalitarian Tide (of 1936)

In October of 1936, the Los Angeles Times described the California campaign visit of Roosevelt’s opponent Alf Landon as “highly encouraging to the Republicans and the real Democrats of this State,” which State, they went on to say, “must pay for New Deal prodigality and folly.” On the radio, they noted, C.C. Teague, president of Sunkist, had “pointed out the choice before the voters in November. They can vote for Roosevelt, and continue a regime tending inevitably to a Fascist or Communist government and the destruction of liberty; or they can vote for Landon and keep America American.”

Just by the way, this Teague was a great pal of Harry Chandler of the Los Angeles Times; the two had joined with MGM’s Louis B. Mayer to smear Upton Sinclair and prevent him from becoming governor of California in 1934, if you can believe. Sinclair actually had quite a good shot at winning the election until this gang got to work on him. They hired an ad agency, made fake newsreels, etc., in the first and maybe filthiest negative political media campaign ever paid for by U.S. corporate interests.

Anyway, back to 1936, where unemployment is still near 20%, and Chandler’s Times denounced the “continued attempts of the President to stir up class hatred and set the “have nots” against the “haves,” claiming that “a division of the wealth of the nation would merely result in nobody having anything above a bare subsistence.” Oh golly, to think that the fatcats could be simultaneously so ludicrous and so transparent, right in the “newspaper.” But I guess that is the same, too; the uneasy marriage of crackpot populism with the naked greed and entitlement of the rich, broadcast far and wide using their very own instruments.

The Times really went to town on behalf of Landon in the last days of the 1936 campaign, concluding with a long report on his election eve radio broadcast, which was a humdinger. The Landon crew had got hold of a Rabbi, a Union Leader, a Woman Educator and Others to complain about the President. These people hardly got a word in about Landon, they were so mad. The Union Leader started by saying that Roosevelt hadn’t solved the unemployment problem. Roosevelt’s distant cousin Alice Roosevelt Longworth (a Republican, of course, and long a fierce opponent,) accused him of “experiments with the Constitution” and making “a farce of democratic government,” and of “using humanitarian agencies for purely partisan ends.” A Boston Attorney railed against “the beginnings of dictatorship,” by which he meant Social Security.

They eventually managed to get a Housewife, Mrs. Arnold Sayer, to mention Landon. “I would feel safer with Gov. Landon in the White House. I think he would run the government the way I run my home — within our means.” (She didn’t say whether or not she could see Russia from her porch.)

Then came a dirt farmer, then the President of Bethany College, and finally “Roscoe Conkling Simmons, Negro orator,” who said, “We are engaged in a contest to determine whether the slave master be returned or whether sons of the establishers of this people shall continue in the way of their fathers. On one side are Landon and Liberty, on the other side are Roosevelt and ruin.”

Faced with this sort of thing — bombarded with it, even, in a manner that some Americans may be able to identify with, nearly seventy-five years later — Molly Dewson wrote another letter to Eleanor Roosevelt just before the election, again rather downcast, and signing herself “Your Gloomy Gus.”

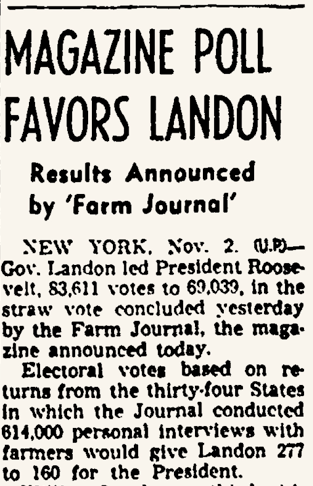

Roosevelt won 60.8% of the 1936 popular vote to Landon’s 36.54%, and 523 electoral votes to Landon’s eight.

Pictures from the Los Angeles Times.Maria Bustillos is the author of Dorkismo: The Macho of the Dork and Act Like a Gentleman, Think Like a Woman.

The People

by Luke Mazur

These days we the people are emoting. And it’s not just Sarah Palin trumpeting around, and Carl Paladino mad as hell. Even people to the left of Attila the Hun are pissed. Jon Stewart’s rallying and calling the President timid. Tom Friedman is sad we’re not number one anymore. Mike Bloomberg is so fired up that he’s endorsed Meg Whitman to become governor of California.

What’s with all these people telling us what, and how, they feel? It very well could be the economy, but I think that the answer maybe has something to do with the word itself: people.

Our Constitutional Law professor was one of those law school professors who was big into the Socratic method. For us Humanities majors in the classroom, the Socratic method unfortunately had less to do with deconstructing why Oedipus is a tragic hero and was more about teasing out the law from a case while simultaneously cornering ourselves in our own mess of words. Which is to say: law school is tragic, maybe. But there were no heroes.

There were anti-heroes of course, and on the very first day of law school we were about to meet one. Most of us were busy being scared to be called on, like we would be for the entire semester. Our professor was busy going on about the Constitution, like he would for the entire semester. This dynamic made the raised hand all the more startling. Who’s that volunteering, we thought. We’ve just begun. A question about the Preamble? Today?

“Yes, Mr. So-and-So?” (We were addressed us by our surnames.)

“Professor So-and-So” — in law school students also addressed profs by their surnames — “who are ‘the people’?”

At first, we didn’t realize this was a ruse. Maybe Mr. So-and-So was being philosophical.

A few beats of awkwardness transpired as our prof found his bearings.

“You may not be serious, Mr. So-and-So, but the question you’re asking is. Does anyone have any thoughts about the query Mr. So-and-So posed?”

We didn’t. We were too nervous. At least one of us was very close to wetting ourselves.

In law school, the people who offered their thoughts, who spoke up in class, were those students most sure of themselves. That day, Mr. So-and-So confidently mocked what we had up until that point been taking very seriously, too seriously even. Our class seemed to meet its common enemy. Really, we were jealous of his chutzpah.

It was the fall of 2006 and we hadn’t yet become the people we were looking for.

* * *

Edmund Morgan argues in Inventing the People: The Rise of Popular Sovereignty in England and America that the word “people” actually has a lot to do with why most of us consent to be governed by a few of us. In order to function at all, governments require accepting fictions. Make-believe, he calls it: “Make believe that the people have a voice or make believe that the representatives of the people are the people.”

Our first stab at governing ourselves was less than successful. When the Founders convened to redraft the Articles of Confederation, they made sure to bestow more power on the government and less on the governed. The drafters of the new Constitution achieved this objective, in part, “by appealing to a popular sovereignty not hitherto fully recognized, to the people of the United States as a whole.”

Morgan explained that many of the Founders had never “been against the natural aristocracy.” But surely they couldn’t say so a few short years after they’d overthrown their royal governors. By a clever bit of wording — the Preamble — James Madison forged a national government “resting for its authority, not on the state governments and not even on the peoples of the several states considered separately, but on an American people, a people who constituted a separate and superior entity.”

OK. But how? While Madison and company had invented the people, they “had assumed an existing social structure in which the people would know and recognize and defer to their natural leaders.” Which is to say: we just understood that we should elect people whiter, richer and more landed than ourselves. And we did it without being told to. We bought into — right away — the system just created to govern us.

This is a very sinister view of things, and in his epilogue Morgan softens our landing. The sovereignty of the people “has continually challenged the governing few to reform the facts of political and social existence to fit the aspirations it fosters.” History sort of bears this out. “The people” was too powerful a rhetorical device to remain simply rhetoric.

Abraham Lincoln borrowed the language when he proclaimed in the Gettysburg Address that “government of the people, by the people and for the people shall not perish from this earth.” Even though he was dedicating a cemetery at the time, his conception of the people would forever change the Constitution and the relationship of the many states to the national government.

Less sublimely, the phrase “we the people” would title our textbooks. The words would be used in stump speeches and on Presidents’ Day car commercials. It wouldn’t be long before Mama Grizzlies and Crazy Carl perverted our founding slogan. The soul of the Tea Party movement, as Sarah Palin explained to her PAC in September, “is the people — everyday Americans who grow our food and run our small businesses, and teach our kids, and fight our wars.” Today it seems we all want a stake in how we do just about everything.

* * *

According to Morgan’s telling of the story, “the people” is how we’d be sold our government. It began as a trick, but then we’d internalize it. We’d start to become it. The Founders were daring us even as they were branding us. And so in that way, maybe that day in law school, both my professor and my classmate were onto something. Maybe the people, well doesn’t it seem like lately — we’re a joke?

Luke Mazur is a resident of Buffalo, NY. Elements of Stale is our irregular grammar column.

Photo from Flickr by Mike Fernwood.

Is Sex Worth It?

“Sex costs amazing amounts of time and energy. Just take birds of paradise touting their tails, stags jousting with their antlers or singles spending their weekends in loud and sweaty bars. Is sex really worth all the effort that we, sexual species, collectively put into it?”

— Spoiler: Yes.