Apple Doesn't Give a Damn About Your iPad Magazine

The New Yorker’s “Dec. 6 issue wasn’t available on the iPad for more than 36 hours, which led several people within the ranks at Conde Nast to speculate that Apple was holding the issue hostage. But why?” Good morning! First Steve Jobs came for the weeklies, but I said nothing, because I was a monthly….

Rock, "Rock Ridah;" Black Rob, "Up North"

Here is Rock, a.k.a. “Da Rockness Monstah,” one-half of the Brooklyn duo Heltah Skeltah, rhyming over the beat to Tupac’s “Ambitionz As a Ridah.” (It is, I think, the best beat of any Tupac song; it was made by Snoop’s cousin, Daz Dillinger, of the Dog Pound.) Fifteen years ago, Heltah Skeltah was a major part of the Boot Camp Clik, a collective that also included Black Moon, Smif-n-Wessun (who changed their name to the Cocoa Brovaz after the firearms company sued them), and O.G.C. (Originoo Gunn Clappaz), and recorded for Duck Down Entertainment, the label Black Moon MC Buckshot started with his partner Dru Ha. Boot Camp were some of the most outrageous spellers rap has ever known, and their music was great.

Around the turn of the century, though, the collective splintered, as collectives will, and Duck Down Entertainment got very quiet for a while. A lot of people probably thought we’d heard the last of them. That’s what I thought. But then, around 2005 or so, Rock’s old partner Ruck found some nice solo success putting out records under his given name, Sean Price. Duck Down started doing good again, representing an underground niche that came out of the “back-packer” scene most famously associated with Rawkus Records — but that was really spurred by Buckshot, who actually used to wear a back-pack onstage during Black Moon shows in the ’90s. So, it’s only right. Heltah Skeltah reunited for their third album two years ago. And Duck Down is busy signing folks like Harlem’s Black Rob, a former Bad Boy Records artist, who had a big hit ten years ago with “Whoa,” but then went to jail, and has been making some very good music since getting out this past May.

Here’s Black Rob’s new song, below. It’s about jail, and kind of harrowing, but also terrific. His album, Game Tested & Street Approved, is due in March.

The Naked Truth About Getting People To Click, Revealed

The Naked Truth About Getting People To Click, Revealed

It’s a trick question! The answer is actually “pageview bait.”

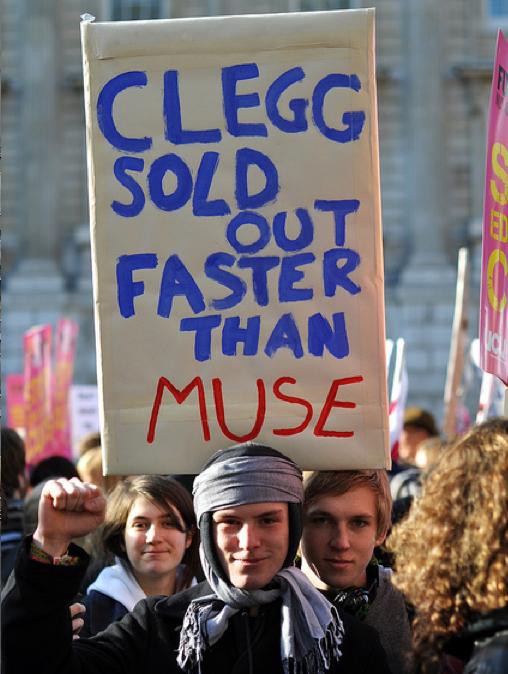

London's Student Demonstrations Are the Best Sort of Education

by Dan Glaun

Earlier this month, students across the UK began protesting against planned increases in tuition fees and the cutting of university services. Today, students have been occupying buildings in Birmingham and hurling snowballs in Edinburgh and marching in London. All of this thoughtful demonstrating — which is winding down in arrests and some clubbings and the offering of mince pies to politicians — takes place against the dramatic backdrop of the first demonstrations on November 10th, when tens of thousands of young people stormed London. At the end, in Millbank, in central London, some demonstrators smashed windows; fires were set; and an occupation of Conservative headquarters by a few hundred ensued (from that building, an 18-year-old threw a fire extinguisher off the roof). Further, the second wave of demonstrations, on November 24, went off with some hitches when some small violence against property ensued and the police cornered and arrested a number of marchers.

The media refers to both the November 10th and November 24th demonstrations as “riots.” (“As Students Rampage…,” headlined the Mirror last week.) So what is becoming lost is what the November 10th demonstration was like for the 30,000 to 50,000 peaceful protesters who flooded the streets outside Parliament in defense of higher education.

My protest experience began at the ungodly hour of 7:30 a.m. in a University of Sussex campus bar. It was serving breakfast early for the occasion. The warm-enough eggs and triangular slabs of hash browns were just one aspect of the institutional support for the demonstration — professors were encouraged to reschedule lectures to allow attendance, and assignment due dates were pushed back a day. The Sussex Student Union had found common cause with an administration seemingly eager to regain students’ good will and stave off government cuts.

In a burst of journalistic arrogance I approached a student sitting intent over his eggs and toast and asked if he’d mind answering some questions. He said that he didn’t mind, his name was Bart, and he was Dutch, in that order; when asked why he was demonstrating for another country’s education system, he replied that it was a matter of social responsibility — and a misconception on the state’s part of what education is: “Basically, you have to pay for your own education because you are the only one profiting from it. And that’s just not true.” Common benefit should equal common cost — as morally clear a belief as any, and one directly contradicted by the reasoning of the Browne education review and David Cameron’s governing coalition.

The Browne review is the polarizing document from David Cameron’s government — which was actually commissioned by Gordon Brown on the way out — in order to reduce Britain’s growing national deficits. You may read it here. The summary explains that Lord Browne’s “recommendations present a radical plan to shake up higher education in England and a charter for choice for students.” The review is now a component of Cameron’s deficit reduction scheme which contains, among various policy suggestions, cuts to social programs, welfare, government payrolls and defense. The most controversial recommendations so far — at least the only ones to inspire tens of thousands to wave signs and yell slogans from the National Gallery to Millibank — are the ones to do with the Browne report. Britain’s higher education system, a bedrock of the welfare state since the 1962 Education Act mandated free university for all, has been steadily eroded since Tony Blair’s Labour administration instituted fees in 1998.

Since then, fee limits increased from £1500 to £3000, as the government tried to shift the funding of universities from grants to tuition. The Browne review would raise that limit to £9,000, as well as eliminating all government funds for the humanities. This has sparked what can only be labeled a shitstorm among students, many of whom voted for Nick Clegg’s Liberal Democrats only to see the party abandon their anti-fees pledge upon forming a coalition with the Conservatives.

Given that us American college students — I am an exchange student — regularly face tuitions of up to $50,000 each year to go to school, the outrage here can have a surreal tinge to it. Then again, we expect our schools to treat us like consumers. In fact, the new buzzword in higher education has administrators calling students “customers.”

I filed into line after breakfast and received a recycled wristband (it was labeled “Sussex Fresher’s Pub Crawl”) to gain access to the coach. The bus filled up quickly and left. Students talked animatedly, hands around cardboard cups of coffee, or leaned their heads against windows and tried to sleep. A tall, pale kid in a hoodie walked the length of the double decker, hawking copies of Socialist Worker; a group of three unnaturally peppy girls carried a large tupperware container of flapjacks, selling them for some cause or another. Luke, a first year student with the red of a Remembrance Day poppy on his blazer, sat next to me. For him, the demonstration was a personal as well as political matter — while he would be out of university before the fees came into effect, his younger brother would have to face the choice of heavy debt or lack of education.

The drive stretched north through miles of English suburbia and countryside. The low November sun bathed the coach and formed shifting, fractal shadows against the encroaching treeline. A black, tapered structure appeared out of the passing fields — a World War II monument, small wooden crosses and poppies arranged next to it in rows. The traffic grew torturous as we passed through the outskirts of London — Coulsdon, Norbury, and Streatham crawling by in repetitious streets of barber shops, Halal restaurants, convenience stores, and one incongruous Papa Johns. Repurposed factories that were now shops littered side streets, defunct smokestacks angled up to the cold blue sky. A banner outside the Stockwell underground station memorialized Jean Charles de Menezes, an innocent man shot dead in 2005 by police who believed him to be a terrorist responsible for the recent London tube bombings.

We eventually made it into London proper, disembarked at the Aldwych Theater, and began to walk to the London School of Economics. Along the way I talked to students. Ellen, a Sussex undergraduate, said that she was marching for her younger sister, while Adam, a student in a pseudo-military getup carrying a sign over his shoulder, was at his first major protest. The commonalities were striking — a lack of major political experience, a feeling of betrayal on the part of Nick Clegg and the Liberal Democrats, and a sense of moral outrage over the government’s abdication of social responsibility.

We crossed the Thames, our numbers growing as demonstrators converged on the rally point. The crowd was vocal throughout, shouting, singing, generally making a high spirited racket. The chants ranged from the traditional — “No ifs, no buts, no education cuts,” a classic of iambic outrage — to the hilariously blunt. Class was a clear dividing point. Shouts of “David Cameron, go back to Eton” were greeted with raucous cheers. Easily the best, however, was a tuneful chant set to “Oh My Darling, Clementine”:

Build a bonfire, build a bonfire

Put the Tories on the top

Put the Liberals in the middle

And we’ll burn the fucking lot.

In retrospect, that reads as some very on the nose foreshadowing for what was to come at Tory headquarters. At the time, however, I chalked it up to an endearing pyromaniac tendency in British politics, coming as it did just five days after the fireworks and effigies of Guy Fawkes Day.

We crowded into a wide alley between the brick and concrete buildings of the London School of Economics, the crowd filing in behind us. Signs dangled from ceilings and windows; a huge blue and green banner saying “Freeze the Fees” was strung from the window of a high rise directly in front of the rally. LSE students and lecturers delivered a series of short, punchy speeches, hitting notes of anger, populism and social justice. A professor shouted his deep sandpaper brogue into a microphone, attacking the “fat cats” who have “wrecked our society,” asking the crowd if any of them were going to go work for Goldman Sachs (he was met with a chorus of boos). “We will not stand idly by while politicians sell our education to the highest bidder,” said one student representative during an impassioned plea for public education and the humanities. The crowd was young and thoroughly multi-ethnic; most carried backpacks. Many took the opportunity to roll cigarettes while standing still.

Then the speeches were over, and with a collective roar the demonstration began its march to Parliament. One student lit a red sparkler and ran through the crowd, trailing smoke and embers behind him. The march grew in size as more protesters streamed in from side streets and were greeted with cheers. With surprising quickness the demonstration’s numbers grew from the thousands to the tens of thousands. Bemused tourists waited endlessly to cross the street as we cut through Trafalgar Square; cars and trucks that honked in solidarity received roars of approval. Bursts of music mixed with the general exuberant volume of the students. A drumline beat a rhythm outside Pizza Express. A brass band reading sheet music taped to each others’ backs played John Philip Sousa’s “The Liberty Bell” march — more commonly known as the Monty Python theme song. An enterprising street vender sold vuvuzelas to the walking masses.

As the demonstration made its ponderous way down Whitehall, I spoke with several protesters about their reasons for demonstrating. Rob, a student new to political action, characterized the proposed fee raises as “just stupid, really.” Trying to draw out a slightly more trenchant analysis of the situation, I asked who he had voted for in the last election and hit the sore spot. Rob had voted Lib Dem, and thought it was “horrific how that they’ve turned against us and fucked everything up.”

Polly, a mother of one future and two current university students, was demonstrating with a sign reading “Angry Mums against Higher Uni Fees.” While there was no visible evidence of widespread maternal radicalism, she assured me that there were many like her out there. A Labour voter, she nonetheless expressed outrage at the Liberal betrayal and thought that Nick Clegg should do the decent thing and step down.

And I met Sam, a long-haired Goldsmiths student, standing on the balustrade outside Her Majesty’s Revenue and Customs building. He had voted Green, and felt vindicated. “I was never going to vote Lib Dems,” he said. “It was obvious from the beginning that they were between a rock and hard place, between Labour and Conservatives, and they’re both bullshit. To be fair to them, that’s what they do. They’re in Parliament.”

The march slowed to a crawl as police held open half the road. After twenty minutes of excessively slow movement, I cut through a traffic jam and jogged down the sidewalk looking for a better view. After climbing on a guard rail, I discovered that the demo had grown staggeringly huge — media estimates placed the top number at around 50,000, but all I knew then was that Whitehall was shoulder to shoulder with students from Trafalgar Square down to Parliament. Finally the rally picked up speed again; the streets were full as it reached its endpoint, thousands upon thousands surrounding Parliament, a student with a camera hanging one-armed off the Westminster station underground sign. There were drums and the constant din of human voices, rising to frantic pitch after each round of cheers or in response to anything, really. A circling news helicopter drew excited mass yells each time it passed over the demonstration. Until then, the protest had seen very limited police presence and, according to one officer I spoke to, had been completely peaceful.

As we walked past Parliament, a woman with a megaphone informed us that the official demonstration was over. Word started to spread of a thoroughly unofficial occupation of Tory headquarters that was taking place a few blocks down the street. That building was a scene of sublimated chaos. A crowd of demonstrators stood on the street outside, steadfastly ignoring pink-vested officials urging them to move along. Inside the semi-circular courtyard, hundreds of students were jammed together as smoke rose from an improvised bonfire and drum-and-bass blasted out of speakers from a staircase. Up on the roof, several occupiers pumped their fists and waved black and red flags to yells of solidarity from the crowd. A University of Leeds banner was hung from the top of the facade to cheers.

The crowd was packed thick and I couldn’t see much, so I jumped a guardrail onto a more sparsely populated stairwell. The entire front window had been smashed; the glass was a spiderweb of cracks, with shards scattered on the walkway leading to the entrance. A line of police officers, ludicrously outnumbered, formed a barricade around the doorway as a spontaneous mosh pit formed fewer than twenty feet from them. A line of riot police carrying batons and plexiglass shields tried to push their way to the door; they retreated after being pelted with sticks from signs and shoved back. A group of demonstrators broke a boom barrier and began to stream around the back of the building, where a few police officers stood guard over Tory headquarters’ parking garage.

A few students were starting another fire on the outskirts of the courtyard, using broken signs and copies of the Socialist Worker for kindling. I walked towards Whitehall. I saw a small group of students blockading a side street, where police reinforcements stood uncertainly and then left. Tom, a protester in a black knit cap carrying a megaphone, said that they’d been blocking the route for around fifteen minutes, and generally demonstrating in the area for a couple of hours. I asked him what he thought about the police retreat: “At the moment the police force here are spread fairly thin,” he said. “They seem to be jumping to different areas of the vicinity, so I imagine they’ll be coming back here as soon as more people start throwing things again.”

If that situation reads like the adolescent fantasy of a kid who just bought his first Dead Kennedys album and feels like it really means something, well, it kind of was. Youths waving banners from the top of a damaged government building, seemingly immune to the police or the vagaries of any authority — it was powerful, and I did get swept up in the mass exhilaration. The slightest moment’s reflection, however, reveals the short sightedness of the violence. For instance, the political consequences to a movement that needs mainstream support to affect national policy, or say, the stupidly dangerous decision to throw a fire extinguisher out an office window with hundreds of people standing below.

The occupation cannot be viewed as defining the protest as whole, or as being separate from it. Given that the two most recent mass demonstrations in the United States were run by a TV comedian and a reactionary demagogue, also from TV, the events of November 10th deserve our respect. They displayed extremity in the form of an articulate, outraged, passionate response to government abandonment of education that drew tens of thousands of committed young people off the Internet, out of the schools and into the streets.

Correction: This post has been updated in one paragraph to properly explain the Browne Review.

Dan Glaun is a UMass undergrad and thinks you’re pretty cool. He is currently unemployed, but prefers the term ‘freelancer.’ He can be reached at dgg20 [AT] sussex.ac.uk.

Photo by Andrew Moss from Flickr.

Will.i.am Rejects The Legitimacy Of Your Criticism

“Will.i.am has recused himself from the questions. He’s just rocking his club, and not badly.”

— Ben Ratliff, in today’s review of the Black Eyed Peas’ new album, The Beginning.

“I consider this tribunal a false tribunal and the indictment a false indictment. It is illegal being not appointed by the UN General Assembly, so I have no need to appoint counsel to (an) illegal organ.”

— Slobodan Milosevic, at the opening of his 2001 hearings before the International War Crimes Tribunal.

Snoop Dogg And Bachelor Parties: A Match Made In A Very Logical Place

“When I heard the royal family wanted to have me perform in celebration of Prince William’s marriage, I knew I had to give them a little something. ’Wet’ is the perfect anthem for Prince William or any playa to get the club smokin’. “

At 4:20 p.m. PT, Snoop Dogg will have a very classy wedding present for the prince: “Wet,” an “anthem made for Prince William’s bachelor party and all bachelor parties around the world to follow.” Somewhere, 50 Cent is bumming over his inability to think of this idea first.

Why The Ads For Christmas Engagement Rings Make Me Uncomfortable

It’s not even December, but the “aggravating trends in holiday commercials” list is already filling itself out quite nicely, and right behind the chart-topping scourge of twee that is Pomplamoose has to be the surge in ads for diamond merchants like Jared, Zales, and Kay, all of which have decided that the best way for a man to celebrate the season is to put a sparkly ring on his intended’s finger. But all these ads are doing for me, a red-blooded American female, is solidifying my belief that that I never want someone in a relationship with me to feel like they have to “propose.”

I can already hear my mother asking me why I don’t like nice things. Take a look at this current ad for the mall jeweler Zales, and maybe you’ll see what makes me squirm?

Those of you who (like me!) have been engaged and who are straight women have no doubt been asked “how he proposed” by inquiring acquaintances, and those of you who (also like me!) just decided to get married and told inquisitive types that have no doubt been met with a bit of disappointment. Which is why in this montage, the men are all smiling smugly while the women freak out at the sight of the gems proffered them, or even just their boxes. The man acts; the woman reacts. It sets a pattern — and maybe provides some foreshadowing for the wild-eyed craziness that occurs in Bridezilla mode. (Perhaps the element of surprise occasioned by the proposal causes that strand of behavior to hit the ground running?)

Sure, a lot of how one views the decision to get married depends on how one views that old, weather-beaten institution. I have not been married but in my perhaps overly romanticized worldview I see an ideal marriage as a partnership, as a combining of two people who enjoy each other and respect each other and see each other as equals and who want to legally solidify that mutual love and admiration, and perhaps throw a party for a bunch of people they like as a celebration of that fact. But the whole notion of the “proposal” set forth by these ads, and other cultural artifacts celebrating it, is a more civilized/sparkly way of Tarzan forcibly throwing Jane over his shoulder. (Not to mention that in the current moment, the whole idea of the man in the heterosexual relationship being the only one who can afford a gemlike token of the sort offered by these shops is a luxury left to either the financially suicidal or the extremely rich. Although I should probably note that I’m also opposed to gross artifacts like that ring women are supposed to wear on their right hands to indicate that they are “available and happy,” because, yuck.)

This is not to say that I’m begrudging the happiness of people who proposed and were proposed to and were happy. Hey, knock yourselves out! But I think that the three months’ salary that would go toward a bauble would be put to better use when combined with the partner’s income over that same timespan, and put toward something that both people could enjoy — a house, a trip to the south of France, or maybe even the marriage celebration itself. (Oh, how much extra money catering halls charge when you utter the word “wedding” …) And the idea that said treat would be something mutually agreed-upon? Would make it only sweeter.

Under the Bridge: The Side Benefits of Troll Culture

by Mike Barthel

The problem with making the Internet safe is that it would necessarily make the Internet the same. That’s the reason Facebook creeps people out: it tries to impose a uniform user interface on the existing heterogeneous online experience to make it appear homogenous, and in so doing actually transform the culture into one where everything is the same. In an op-ed in today’s Times, Julie Zhuo, a product design manager at Facebook, goes further, proposing that non-Facebook content providers standardize their approach to anonymous commenting to rid the Internet of trolls. (Or hey, maybe they could just use the Facebook commenting system!) But what would the Internet be without trolls? Hell, what would New York City be without trolls? Denying the ability of different online communities to respond to disruptive or contrary commenters in a way that reflects the values of that community ultimately denies the wonderful cornucopia of microcultures that is the fantastic, awful Internet we all know and (mostly) love.

Most writing on what makes a “good” online community tends to come from people who are, let’s say, a bit too rational for their own good. They tend to assume that there is no such thing as an online community other than the ones they participate in. Oh, sure, alternatives may exist, but they are simply less-evolved versions of the Platonic type inhabited by those paragons of substantive discourse known as “computer nerds.”

I’m thinking here of Slash, the open-source message-board and news programming that has as its most visible component the undeniably innovative commenting system displayed on ur-nerd site Slashdot. Instead of just listing all comments chronologically or in threads, users voted for which comments were the best, and you could then set your filter to only show highly-rated comments and/or commenters. I used it extensively on the post-Suck discussion board Plastic (where, somewhat distressingly, my username still appears in the top-rated posters list), and I liked it! But my subsequent experience in other communities showed me how other forms of filtering could work, too.

And these systems tend to both be informed by and promote the values the community is interested in promoting. For instance, if I may be so bold, the Awl is interested in a sense of empathy and collective enthusiasm, so commenters reward people who promote these values (by replying en masse) and ignore commenters who don’t, thus encouraging people interested in becoming part of the community to conform to the community’s values.

The current incarnation of Gawker, meanwhile, seems overall interested less in community than in making commenters a form of unpaid content contributors, which is why (at least some) editors promote particular comments based on entertainment value and legibility rather than creating a shared identity. Another forum to which I previously contributed was (or became, anyway) more gladiatorial in tone, and newcomers were roundly (and sometimes unintelligibly) mocked until they learned to hold their own in a way the community could respect, which reflected values of shared knowledge-building over inclusion or engagement. And you can think of the values of mommyblogs or neighborhood blogs or religion blogs as places where different values might lead to different attitudes toward anonymity and new contributors.

What interests me most, though, are those feminist blogs and bloggers which seem to consistently engage with people who wander in and say something clueless and/or confrontational. This strikes me as extremely brave and impressive, representing a commitment to dialogue and discourse above, say, one’s own time and sanity that I simply cannot manage myself. (Just one recent example.) I’ve never been an active participant in these forums, so I certainly can’t say for sure that this is what’s going on. But it seems to me to represent a true translation of feminist values into action, and as frustrating as these debates can sometimes be to watch and (from what people say) engage in, it is truly walking the walk by talking the talk: they refuse to silence people even when they know they’re wrong, and can only be content through extreme engagement with the other point of view.

And it is particularly that kind of relationship between a community’s values and a community’s commenting system that a standardized treatment of anonymity and commenters would erase. Not all online microcultures want to engage with every ill-informed yokel who staggers in to blurt out an opinion, and for them, there are certainly options. But eliminating anonymity and encouraging everyone to act online in the same way they would in real life essentially ruins the point of going online in the first place. There’s a real value in being able to try on different identities and code-switch at will rather than by necessity. And there’s a real value in communities being able to enforce their particular values rather than those of society at large. I don’t act everywhere like I act on the Awl, but I would like to! If my comments here are held accountable to everyone else I’ve ever known, then I can’t do the Awl-specific things that are such fun.

The ultimate counter to all this, of course, is 4chan. But that seems undeniably like one of those “I disapprove of the fact that you have a child-molesting bear meme, but I will begrudgingly grant your right to do so, I guess” kind of situations. As awful as 4chan (or /b/, or anon, or whatever) is, it’s certainly something, and it would be impossible without the entirely unique commenting system it has in place. It’s totally illogical and yet, somehow, it works. It is a form of communication made possible entirely by the Internet, and it seems not only like a shame but like an impossibility to lose that. It would make more sense, instead of trying to find some universal solution to the problem of trolls, to look at the ways in which individual communities have dealt with the issue and admit that every venue will have to design its own solution unique to their context. Facebook wants to make everywhere online the same, and I don’t think they’ll be able to. But I also wish they’d stop trying, if only so we could have a more productive discussion about the whole matter. If anyone is the troll in this debate, it’s Zuckerberg and company.

Mike Barthel is not trolling on his Tumblr.

Climate Change: Reasons For Optimism

“At least the weather will be better.”

— Christiana Figueres, executive secretary of the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change, compares this year’s UN climate change conference in Cancun, Mexico, to last year’s grim affair in Copenhagen. Cheer up, Christiana! Pretty soon the weather will be better in a whole lot of places.

The Geometry Of Molecular Gastronomy

“Chefs, among them Hes ton Blumenthal of Bray, England, New York City’s Wylie Dufresne, and Chicago’s Grant Achatz, have taken to foaming all manner of savory foods. These dishes have an aura of mystique about them and not just for their novel texture. Although foams may look like random jumbles, the bubbles within all foams seem to self-organize to obey three universal rules first observed by Belgian physicist Joseph Plateau in 1873. These rules are simple to describe but have been remarkably hard to explain. The first rule is that whenever bubbles join, three film surfaces intersect at every edge. Not two; never four — always three. Second, each pair of intersecting films, once they have stabilized, forms an angle of exactly 120 degrees. Finally, wherever edges meet at a point, the edges always number exactly four, and the angle is always the inverse cosine of –1/3 (about 109.5 degrees).”

— Foam is scientifically interesting. But I still wish chefs would stop trying to pass it off as sauce. Because it doesn’t taste as good.