East 45th Street, New York

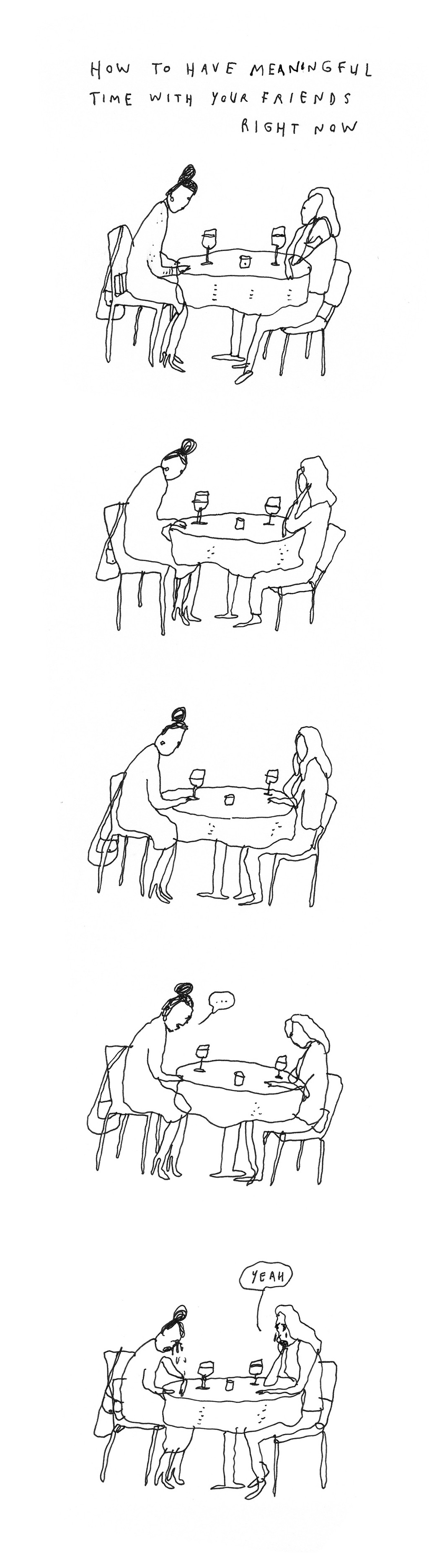

Illustration: Forsyth Harmon

I saw you out the window of an Uber pool, from which melancholy comes easy. My fellow passenger was a young Middle Eastern guy speaking extremely quietly into his phone. J’ai compris Maman… Non, non, j’ai compris… Ne t’inquiete pas. The app had told me “You are riding with Quentin” and it seemed a sort of violation to know his name, too intimate. I looked out the window in a very studied and committed way, hoping to invest this stance with complete absorption so as to grant him a sense of privacy. But I couldn’t not hear, and the quieter he spoke, the more my ears strained.

When he’d appeased her enough, and hung up, he stared out of his window and I stared out mine and at least one of us was thinking about how many other mothers might be telling their brown children to be careful tonight. The president-elect had just appointed a white supremacist as his chief strategist.

We’d shared this car into Queens, through the Midtown tunnel, into the city and its traffic. By now the car was edging in increments of hand spans, a little lurch forward every few minutes, bumper to bumper. Slow progress in the evening rush. Slower than the people on the sidewalks, whose quickly passing bodies seemed to blur in the dark evening and the storefront lights. I reminded myself they were all real, each one.

I thought of that speech I loved in Anomalisa, Charlie Kaufman’s stop-motion film. The protagonist, the fuzzy-skinned little puppet-man, eerily real and human, speaking in his humdrum British voice as he addresses a customer service conference: “Each person you speak to has had a day. Some of the days have been good, some bad. Each person you speak to has had a childhood. Each has a body. Each body has aches.”

You were a young white woman in Uggs and a green parker jacket and your day, I think, had been a good one—few aches. You and your boyfriend were walking and talking fast, some place to be. But then he said something to you, grinning with the anticipation of your reaction. You doubled over with laughter right outside the Roosevelt Hotel — just stopped, in the stream of foot traffic, bent over so far you were basically squatting — hands on your knees, eyes shut, convulsing, overcome. You made laughing look like giving birth. And he was already a pace ahead so he stopped too, turning back and giggling at the sight of you, waiting for you to recover while the hotel porters raised their eyebrows and smiled at the spectacle you made.

I smiled too. I didn’t begrudge you this: that it was easier for you to laugh tonight.

What To Read This Weekend

The only post-election piece you should really bother with.

There’s a monster of a piece in next week’s New Yorker that will serve as a temporary salve for your aching brain, for at least as many minutes as it takes you to read it. David Remnick offers a glimpse of last week’s events through the eyes of the guy getting evicted from the White House at the end of January. President Obama is as maddeningly calm and and sly as ever, winkingly telling Remnick he’d say how he really felt about the election result at some future date—off the record, over beers.

In some ways, it is Obama’s job to give this big interview, to calm the worried liberals, to reassure Democrats that what they have to do next is not only achievable but necessary. Of his strategic equanimity in receiving Trump for a visit at the White House, Remnick writes:

Obama was also trying to engage the world in a willing suspension of disbelief, attempting to calm markets and minds, to reassure foreign leaders and, perhaps most of all, millions of Americans that Trump’s election did not necessarily spell the end of democracy, or the rise of an era of chaos and racial enmity, or the suspension of the Constitution. This is not the apocalypse.

Obama’s insistence that this is going to be okay because this is what we do and this is the process is only so helpful, and I’m sure there are a lot of people who wish he were more angry on their behalf. But he insists this is how he really feels, and that he does not need a Key & Peele “anger translator.” “Look, by dint of biography, by dint of experience, the basic optimism that I articulate and present publicly as President is real,” he tells Remnick.

“It’s what I teach my daughters. It is how I interact with my friends and with strangers. I genuinely do not assume the worst, because I’ve seen the best so often. So it is a mistake that I think people have sometimes made to think that I’m just constantly biting my tongue and there’s this sort of roiling anger underneath the calm Hawaiian exterior. I’m not that good of an actor. I was born to a white mother, raised by a white mom and grandparents who loved me deeply. I’ve had extraordinarily close relationships with friends that have lasted decades. I was elected twice by the majority of the American people. Every day, I interact with people of good will everywhere.”

Isn’t Michelle just the luckiest? There’s a feeling throughout this interview that Obama is being the wise dad at the end of the family sitcom. So this week’s planned activity didn’t pan out the way you thought it would? Let’s sit down on the edge of the bed and let me put this into perspective for you. The ultimate this too shall pass. There’s also the feeling that we’re going to remember Obama as one of the best dads we’ve ever had, at least in a sociological sense:

Obama is a patriot and an optimist of a particular kind. He hoped to be the liberal Reagan, a progressive of consequence, but there are crucial differences. For one thing, Obama does not believe in the simplistic form of American exceptionalism which insists that Americans are more talented and virtuous than everyone else, that they are blessed by a patriotic God with a special mission. America is a country that was established on the ideas of Enlightenment philosophers and improved upon not merely by legislation but also by social movements: this, to Obama, is the real nature of its exceptionalism. Last year, at the fiftieth anniversary of the Selma-to-Montgomery march, he stood on the Edmund Pettus Bridge, in Selma, and defined American exceptionalism as embodied by its heroes, its freedom fighters: Sojourner Truth, Susan B. Anthony, John Lewis, the “gay Americans whose blood ran in the streets of San Francisco and New York”; its Tuskegee Airmen and Navajo code-talkers, its 9/11 volunteers and G.I.s, and its immigrants — Holocaust survivors, Lost Boys of Sudan, and the “hopeful strivers who cross the Rio Grande.”

It is heartbreaking to think that Donald Trump won by, among other things, stoking a pervasive fear of these hopeful strivers who made America so great in the first place.

Of the ninety-minute meeting with Trump in the Oval Office, Remnick writes, “Obama had steeled himself for the meeting, determined to act with high courtesy and without condescension.” One wonders whether the president-elect will be capable of same when his turn comes to gracefully pack up and salute the next poor soul into the hot seat.

Finishing the piece may not convince you fully that just because this isn’t the end of the world doesn’t mean it’s not pretty miserable to live through. But it will have the effect of a warm, caring hand rubbing circles on your back, maybe brushing your hair aside as you spit up the last of the bile. It’s not over, you won’t ever really get used to the nausea, but at least now you know how to live with it.

You can read the rest here:

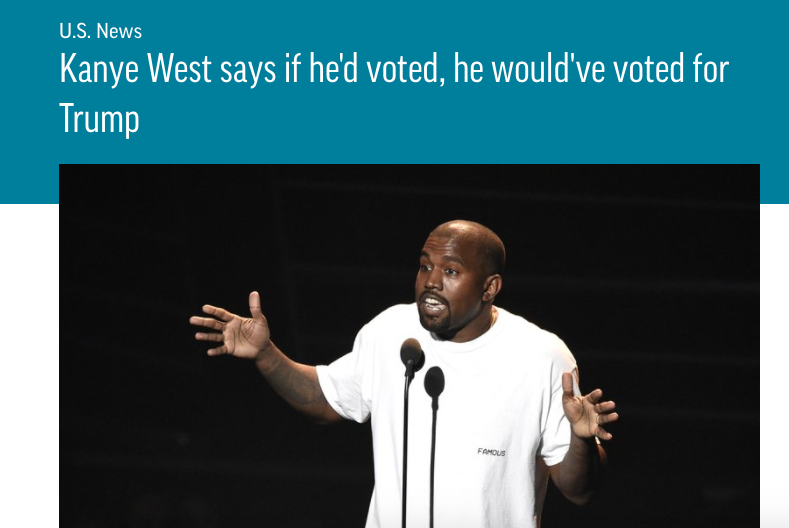

If I Could Make Headlines As Easily As Kanye West

Here is what I would do

Christine Friar says if she’d ordered Seamless last night, she’d have ordered rigatoni.

Christine Friar says if she’d replied to your email, she’d have said, “Congratulations on your recent life milestone!”

Christine Friar says if she’d gone to your wedding, she’d have ordered the chicken.

Christine Friar says if she’d remembered your name, she’d have said hello.

Christine Friar says if she’d lent you her car, she’d have put a little gas in the tank for you too.

Christine Friar says if she’d rolled the dice, she’d have rolled a twelve.

Christine Friar says if she’d learned how to build a house, she’d have a house.

Christine Friar says if she’d been drafted in the NFL, she’d have been MVP three years running.

A Tribe Called Quest, "We The People..."

At least the week is over. Also, at most the week is over.

It’s Friday, it’s sunny and it will be in the 60s today. Those are the three things I can tell you that will feel any good. Other than that it’s another endless day of anger, absurdity and regret. I can’t even imagine how these are going to weigh on us when the weather gets rough. Anyway, if you thought there was any other choice with which to go into the weekend than the new video from A Tribe Called Quest you don’t know me at all. Here it is. Enjoy.

New York City, November 16, 2016

★★★★ A lip and a heel and a fingertip were each starting to crack from the chill. Puddles lingered in the shadowed schoolyard. Workers swept up leaves to fill a fat, crumple-sided sack; dogs trembled or shivered where they waited with their leashes fastened to the fence. By the river, where workers were taking the big brass letters off the buildings, the cold got into bare hands. Bright specks glittered in the dark ridge of construction dirt where finally, having exhausted all means of delay, the developers had belatedly started to build the public park they had promised. The trees by the boulevard, still small enough to seem provisionally installed, had achieved rich russet and yellow.

Holiday Dread: Christmas Trees

Some evergreens I have not loved.

I was raised in a household of Conservative Judaism. This meant that we were the middle level of Jewish. We weren’t irresponsible bacon-eaters like the Reform Jews. We weren’t actually beholden to God on practical matters, like eating or going to the bathroom. We just had to act like it sometimes.

Although I found out later that Christmas trees were pagan artifacts, and cool, I was at first made aware of their presence in our lives only as institutionalized insults. Christmas trees — unavoidable, invasive, and fetishized at what seemed a perverse intensity—reminded me that being Jewish was not as universal as it almost always felt, in aberrant 46% Jewish Livingston, New Jersey. My parents agreed with and encouraged my anti-assimilationist concerns. Kid-lit from the Temple Beth Shalom book fair seemed not totally coherent on the subject.

On one hand, you had The Devil’s Arithmetic, a horrible nightmare story about a reckless Jewish teen whose punishment for ALMOST skipping Passover (because Easter is more fun and you get candy) was getting transported back in time to the Holocaust. That book hoped you would be a good kid and help preserve your culture, or else. Then there was There’s No Such Thing as a Chanukah Bush, Sandy Goldstein. This was a book I didn’t like because it suggested that there was such thing as a Chanukah Bush (condescending), and worse, that I might like to have one.

Here are five tree memories. Happy almost-solstice.

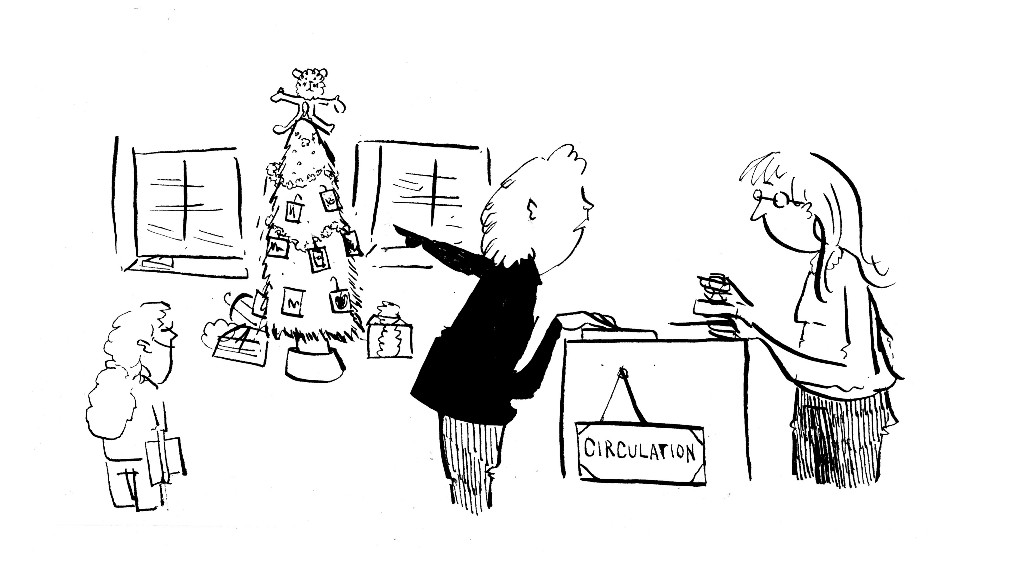

Complaining about the Christmas tree at the public library.

The library was a safe space. I felt unsurprised but still disappointed that they were cooperating with the status quo so shamelessly. This one is a little dim, but I think I was both embarrassed and gratified that my mom led this small act of civil disobedience. It was just like, damn right, we’re not gonna take this.

Christmas tree and Golden Retriever at home of friend.

This combination was disconcerting. I also found it weird how you could just eat a ton of candy and no one cared. It felt familiar, like a trap (see: Hansel and Gretel, Edmund’s Turkish Delight binge via the White Witch.)

A Christmas tree in the bathroom.

My best friend, a year or so after we had graduated from college, was living in a big house with her non Jewish boyfriend. We talked about whether it was acceptable to let your partner have a Christmas tree. She was like, “He can have a little one in the bathroom.”

Sandy Goldstein

That sycophant!

The Christmas tree at Rockefeller Center.

Incongruously, this tree was given a pass by my parents as being okay and cool. I’m not sure why. Maybe because its status as a New York City landmark conferred some Jewish cultural capital onto it? The Rockefeller Center tree was less neutral than Charlie Brown Christmas, but more neutral than the character of Santa Claus doing anything.

Holiday Dread is The Awl’s series dedicated to the season of joy and other emotions. Previously:

Why Is This Fish Kill So Beautiful?

Death, tessellated.

Do you know what a fish kill is? It’s when a large population of wild fish dies in unison and all of their bodies just float there, smelling. Sometimes it’s because of pollutants, but health factors like water temperature, oxygen levels, and the tide can also do them in.

Massive fish kill clogs Shinnecock Canal. Find out why this happened. https://t.co/KfI5TE22Kn Photo by Amy Beth Stern

— @EHStar

This week, in Hampton Bays, NY’s Shinnecock* Canal, thousands of bunker fish (a bait fish used in lobster traps) appeared dead in the water overnight. Initially people were like, “The environment is over!” and “Trump’s presidency has ushered in the end of days!” which, yes, but logistically what experts think happened is the bunkers were chased into the canal by a school of predator fish, and then the canal closed for the night, locking them inside. Crammed into a small space with limited oxygen flow, the school eventually ran out of breathable water and suffocated en masse, holding each other in their final moments like that elderly couple on the bed in Titanic. When the canal opened in the morning, all the water came rushing out, and with it… so many dead fish.

I bring all of this up because a) it is fun to learn new things, but also b) the photos of the dead fish are really beautiful. Something about the repetition of borderline identical shapes over and over again in a place they don’t belong is soothing. Like when Buddhist monks do elaborate sand art and then destroy it when they’re done as a comment on impermanence and the value of creating anyway. “Here is a remarkable visual, and it will only exist briefly, but that is fine—you will have the image in your brain and maybe you will reflect on how it got there.”

This is pretty disturbing...this was the Shinnecock canal this morning

It made me wonder: Are fish kills always this… lovely? Or is this week’s a standout example? From what I can tell, it looks like the answers are no and yes. The two most important factors seem to be the number of fish we’re dealing with in such a small space. News12 Long Island has described the school as “massive.”

If you have a massive amount of fish in a bigger space, like a river, they sort of cling to the shoreline like seaweed and beer cans do. It skips the “art” phase and rockets right into “icky.”

And when it comes to the ocean, even a huge pocket of fish can end up looking like plain ol’ bubbles from a boat.

Now let’s say you have a bigger fish. Maybe the impact of that visual would be stronger because you can really see their bodies? Evocative! But from what I can tell, that’s another dead end. The bigger the fish, the less poetic things get. Here is a river fish kill that happened after a drought caused too much water loss, and I think we can all agree that one hundred big dead fish doesn’t quite provide the same stunning image that seven dillion tiny dead fish piled on top of each other does.

So it would appear the aesthetic requirements for a photogenic fish kill are: small fish, small area, lots of fish. An unlikely combo. And one that’s probably best facilitated by a man-made obstruction to a fish’s natural behaviors, like a canal or a decorative pond.

So while what happened in Hampton Bays this week isn’t necessarily a sign of intensifying climate change, or our president-elect’s power to enact large-scale catastrophe, it is a reminder that we can be (and often are) quite dumb simply by going through our days. And that our decisions about things like moving a boat can have very real repercussions for lives that seem totally unrelated, even if we don’t realize it.

Damn. Fish kills.

______

*hehe

Holiday Dread: Being A One-Plater

Thanksgiving is a competition and every year I lose

The thing about Thanksgiving is that there aren’t really any traditions for it other than eating a ton. Like, yes, maybe your family throws the pigskin around, and there’s certainly the whole colonialism thing, which I don’t mean to downplay, it’s just not what I’m here to talk about.

I’m not sure when I decided that the meal was a sport in itself. The goal is to eat so much until the overwhelming weight of your indulgence causes you to fall asleep. The syndicated comic strip “Foxtrot” used to make this an annual gag, with teen jock Peter often devising absurd ways to fit more food into his stomach. This included, at one point, pre-stretching his clothing. (Come to think of it, my other comic love, “Garfield,” was also unapologetic when it came to food.)

So: eating. That’s the point of Thanksgiving and one could make a very strong argument that it’s the point of America. Just gorging and feast until we pop a belt buckle. If you don’t eat yourself into a coma, you’re downright unpatriotic.

But the thing is: I’m a one-plater. Maybe two as I aged into my teenage years but I cannot recall ever reaching plate three or four. The cultural myth of Thanksgiving is that it’s a marathon, you eat for hours, and when your plate is empty, you get more. Mix it up: maybe some turkey now, maybe some sweet potatoes later, whatever you’re sick of can be replaced. That’s not really how I operate. I get one plate with a little bit of everything and that’s pretty much it? I’m not even saving room for dessert!

It’s not even peer pressure. Nobody really gives me shit for not eating a lot, I just feel obligated to do it. I think “this year’s the year that I fulfill my social obligations and eat way too much food,” but it never happens. Nobody is keeping track, and yet I know. And I’m always a little bit disappointed in myself.

Holidays are competitions. Who can get the most presents on Christmas? Who can set off the most fireworks on Independence Day? Who can be the most apologetic at Yom Kippur? Who can plant the most trees on Earth Day? There are metrics. What am I supposed to do on Thanksgiving? Watch the parade really hard?! (For the record, I am great at this also.) On Thanksgiving, the primary metric is “food consumed.” And I’ve never met my quota.

This has been happening for years. I try my best, I really try to hunker down and commit, and then I just get full and tired really quickly. I used to think it was the tryptophan, but apparently that’s a myth? So it’s all mental. It’s all my idiot brain and skinny frame preventing me from achieving my full potential.

On the plus side, I get more leftovers.

Holiday Dread is The Awl’s series dedicated to the season of joy and other emotions. Previously:

Let's Finally Talk About Beethoven

It’s Beethoven! I’ve been writing this column for weeks and I’m finally getting around to Beethoven, which is a little terrifying, I’ll admit. The other guys I’ve written about, the Romantics and the twentieth-century weirdos, have a little less name recognition and feel like deeper cuts. I mean, Beethoven is Beethoven. There’s a dog and everything.

There are, um, a fuckton of Beethoven pieces, several of which I hope to write about over time, but I wanted to start with the Sinfonia Eroica, his third symphony, also known as the “Heroic Symphony.” A fun fact: it took actual years of my life to learn that “eroica” doesn’t translate to erotica; it translates to heroic.

The Eroica, as it’s perhaps most often called, was completed in 1804 and debuted in 1805, which would have our pal Ludwig van be in his mid-thirties. It’s strange to think of Beethoven as a young person (young-ish, at least) when most cultural interpretations of him have been of him as an angry, deaf old man. (Does it make me a bad person that my go-to image for Beethoven is John Cleese yelling at Graham Chapman in drag?) Despite his age, Beethoven’s hearing loss was already very significant at this point. In 1802, presumably soon before if not during his composition of the Eroica, Beethoven drafted a letter to his two brothers, expressing his despair over his loss of hearing. He maintained that the only thing that kept him from committing suicide was an obligation and love for his art.

Beethoven would go on to compose for another thirty years after his hearing loss, but it signified a major change in his composition style, and many of his works following the Eroica followed suite. Eroica was written for Napoleon — Beethoven dedicated it to him, and then undedicated it to him, then dedicated it to one of his patrons, then sort of re-acknowledged Napoleon when he died. The Eroica was also much longer than many other symphonies at the time: its entire first movement is the length of most contemporary symphonies. Audiences at the time found it boring and confusing. Keep in mind that many symphonies at this time were just variations on the same theme. For four movements to be so different from one another and long, to boot, was deeply disorienting and weird for audiences.

It’s not quite programmatic music — there’s no direct narrative about Napoleon here, it’s more inspired by him — but it does sit right on the cusp of Classical and Romantic styles, mostly due to the time in which it was written. There’s a tone of admiration and greatness reflected in it. Regardless of the back and forth about whether or not this has anything to do with Napoleon — I’m calling it now: it does — it’s about Beethoven’s respect for power and a hopefulness that good leaders can triumph in the face of adversity. It starts with two big round notes announcing itself: this is how the world is going to be now.

The first movement, the Allegro con brio, is perhaps my favorite, and it feels the most traditionally classical. The main “theme” of the piece passes through each section of the orchestra with various interludes.

The second movement is perhaps the strangest — rather than a traditional adagio, Beethoven wrote an imagined funeral march. Is it strange to write a funeral march for a guy you don’t know who isn’t dead yet? I don’t know! It’s the past! Anything goes. The funeral march has perhaps saturated the most into pop culture: it was played on F. Scott Fitzgerald’s deathbed, as well as at the funerals of our two most well-liked initialled presidents, FDR and JFK.

The third movement, the Scherzo — Allegro vivace, brings the symphony back to its initial energy of the first movement. There are wide, sweeping strings throughout, peppered in with French horns calling out like a fanfare. The Scherzo — Allegro vivace almost reminds me of riding music, galloping along in an Austrian countryside.

The final movement, the Allegro molto, feels like the very traditional type of Beethoven-ian music we know now: upbeat, optimistic, sweeping, and grand. It starts fast and furious string melody then devolves into a quiet pizzicato (which means the strings players are plucking the strings with their fingers rather than drawing a bow across them) and builds itself back up from the ground. The old melodies come back, somehow more textured and nuanced than before. It’s like hearing a song you love on the radio; the familiarity is warm and comforting. The final two minutes of the piece are just, like, if you don’t like Beethoven, what’s wrong with you? It’s a bouncing, roaring finale. It’s done.

The thing about Beethoven is more or less: he’s amazing, he’s prolific, he’s fucking revolutionary. These guys, Mozart, Haydn, what have you, lay the groundwork, but then Beethoven came in, dabbled in the classics then rewrote the rulebook all while losing his hearing. HIS HEARING. Even Mozart said at the time, “One day he will give the world something to talk about.” It’s hard to be glib or unserious about him, because so much about him is about creating art in the face of disability. Anyway. This is the type of thing to listen to and to feel good and strong about what you are capable of doing. Like make a website like this. This website owns.

Fran Hoepfner is a writer who used to be a musician, but not in an acoustic guitar sense, more in the the movie Whiplash sense. As kids her age discovered the popular music of the early ’00s , Fran spent 10–15 hours a week in private lessons for piano or playing timpani in several Chicagoland youth symphonies. Because of that, she didn’t discover pop music until 2008, and now her music library is almost exclusively classical. You should listen to more classical music, not for any self-important reason, but just because it’s more accessible than you think it is. Also it’s very good.