Where You Leaves, I Will Follow

Sweet meaninglessness in “Gilmore Girls”

I’m a white woman from Connecticut, so watching “Gilmore Girls” is a bit like seeing myself in a Snapchat filter: horrifying and narcissistically compelling. Do I… sound like that? Do people… perceive me this way? As I’ve mentioned before, the show and I are in a bit of an S&M relationship; I hate virtually everything about it, and continue coming back for more. Which is why I watched all four 90-minute episodes of Netflix’s reboot when they dropped this past weekend.

Sure, the new installments have things like dialogue and character development, but what felt most familiar to me (and what I was most surprised to find comfort in) were all of the minor technical problems that carried over from the original series. There are definitely some particular weirdnesses the show asks you to not pay attention to in order to enjoy the universe they’ve built, and while little things like “the blue on the fake Connecticut license plates makes them look more like Minnesota plates,” are easy to notice once and then never think of again, there are others I love to announce and review like a football referee.

Take, for instance, the issue of “winter.” “Gilmore Girls” has always been filmed on a lot in Los Angeles, and in the original TV series, there’d often be palm trees visible in the background as people were, say, walking up the front paths to their houses, or strolling past windows. They were often quick shots, little three-second establishing angles where the directors probably assumed we’d be reading a sign or paying attention to dialogue, but where I was playing a regional equivalent of the game from the back of Highlights magazine: something about this picture is off. Can you spot it?

“Hehe,” my brain would say every time I caught a desert plant jutting out from behind a New England colonial home. “There are no trees like that in Connecticut. This show is pretend!” Good for you, Christine. So smart.

While I didn’t spot any palm trees in the reboot, I did find a related game to play right in the very first episode. It starts about five minutes in.

“I smell snow,” Lorelai wistfully announces to Rory. And then fluffy TV flakes begin to romantically drift by while the camera pans out to reveal… a verdant-ass oak tree behind them.

“Hey,” you might be saying. “Don’t leaves change colors in the fall and then die, signifying the turn of the seasons?” Yes! That’s true. Which means that anytime there is an outdoor leaf in a scene in this episode, and anytime that leaf is green, it is a continuity error.

Granted, the earth isn’t perfect. Sometimes it snows before it’s been cold long enough for the leaves to drop, and in that case, the living leaves get shocked pretty quickly and turn brown, clinging to the branches like haunted mummies. Then they fall when the wind blows them hard enough. From the looks of it, Stars Hollow already has an inch of two or snow on the ground to begin with, so what I’m saying here is that Stars Hollow trees aren’t like regular trees. They’re different.

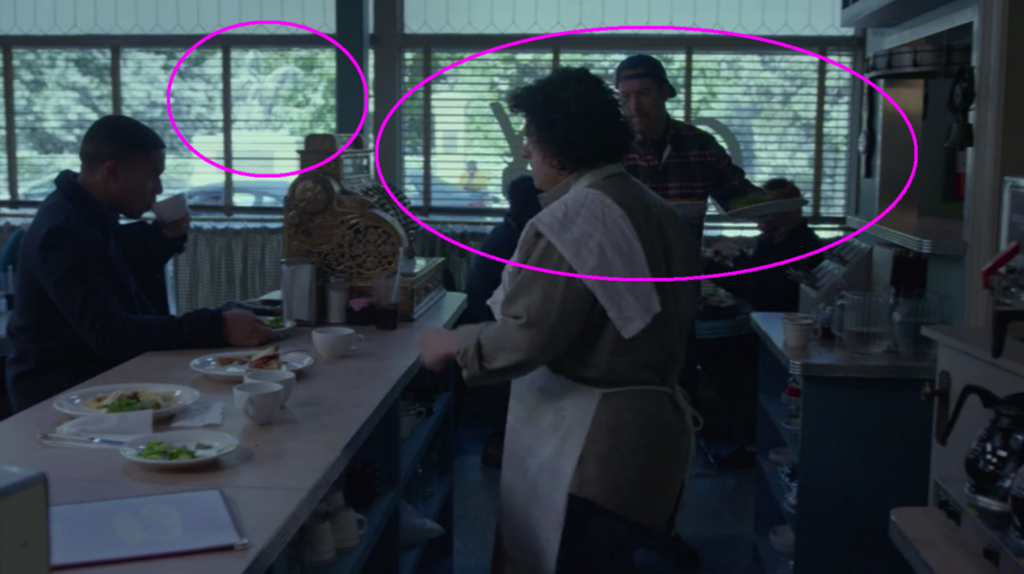

Doesn’t matter if you’re at a diner seething at your customers:

Or catching up with old friends:

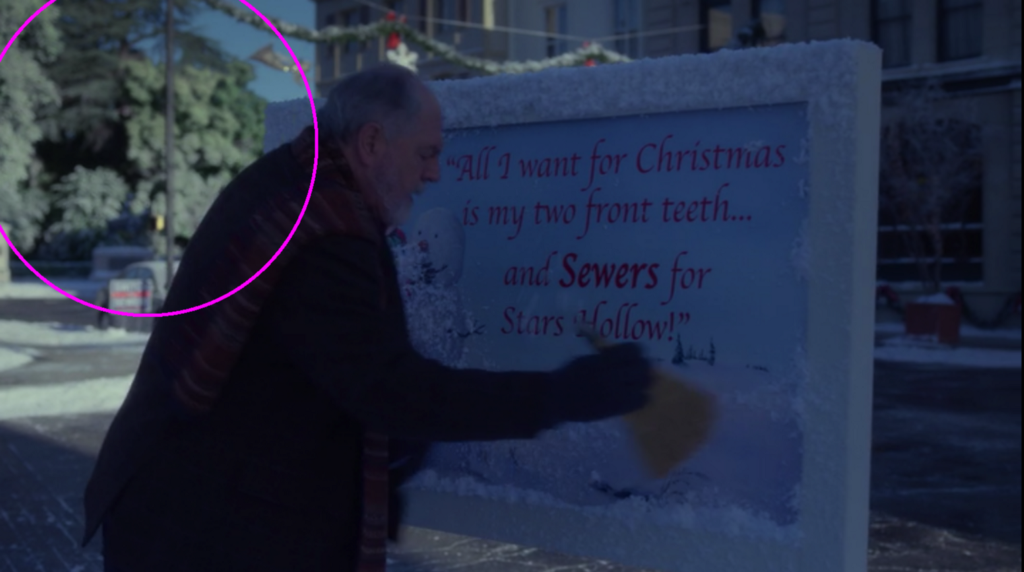

And if you think petitioning your constituents to invest in a new sewer system will save you, think again:

The leaves are even able to withstand the sound of you playing your acoustic guitar in the street at night:

And that is what I love most about Gilmore Girls, I think. It makes no sense and it doesn’t care if you like it. Inspiring.

Woodbridge Sauvignon Blanc

The Nevada City Wine Diaries

Before going to Augusta, Maine, for my dead friend’s visiting hours, I was in New York for something else that I didn’t exactly have to go to but sort of did. New York involved a lot of revelry and putting on and taking off coats. It was the same as always except under the now two-week-old veil of despair about Trump. Every conversation was some version of “How scared are you” “I don’t know, how scared are YOU?” and, additionally, in my case, “Your friend was murdered? What the FUCK?”

I had taken a redeye to New York Monday and slept soundly only once while there. Friday afternoon, I got on the train to meet my father in Boston and drive to Maine full of so many kinds of grief that I felt like I was almost becoming a different person. I also sensed I was getting epically sick, but I hoped that was just part of the molting process. All I wanted to do was get to where I was going, watch two episodes of The Crown, cry, and fall asleep. My mother was already with the family of my murdered friend. So my father picked me up alone.

It quickly became clear that we were not well matched to spend time together at this juncture in history, in a car, in traffic. We were both horrified that Trump had won the election, but I was horrified in a despondent, terrified way and my father in a reflective, we’ve been here before, I-refuse-to-boycott-the-Patriots kind of way. He didn’t have a lot to say about the ways that he was horrified, while I had quite a lot. Plus, there was why we were even here. “I’m sorry I’m so depressing,” I said. “I’m just — depressed.” My father managed a laugh at my turn of phrase.

“Do you want to hear a funny story?” I said, a few mile markers into a protracted silence.

“Yes,” he said vehemently, “I do.”

I told him how I had spent the morning agonizing over whether I should be honest with a friend about a shortcoming of hers, and when I finally was, she managed to not hear me at all. “She just carried on as if I hadn’t said anything,” I said. My father said nothing. “That’s the funniest story I have,” I said.

I searched for a place to eat that my father would find unpretentious. We used my Google maps to get there. “Take the second right after the rotary,” said the Google map voice.

“What do you call her?” my father asked.

“What?” I said.

“Your mother and I always give the GPS lady a name.”

I felt very sad and then sadder because I did not want to have fun. “Sorry,” I said. “I guess I don’t really have a good sense of her.”

I started crying while we were eating and then drank one IPA and felt good for ten minutes and then worse. While my father was in the bathroom I paid. This was unprecedented. I mean, if my parents are around I don’t even let my eyes wander in the vicinity of a check. My father actually thought I was joking when I said I paid already and took out his wallet. “No really,” I said, as the waiter set down my card and the slip. My father shook his head in astonishment. “I feel it’s the least I can do for being such bad company,” I said.

There had been traffic in Boston, but then there was traffic in Maine. Well past Portland, long past summer. “What the fuck?” I said. “Is every single person who lives in Maine driving right now?”

My mother told me she’d gotten us a nice AirBnb and the whole time we were driving I dreamed about some modest furnished rooms, with World Market sofas, and a small bedroom. I would watch my show and then I would maybe cry and then I would sleep for ten whole hours and wake up and have a cup of black coffee. Maybe there would just be a pullout bed. But that would be fine too. I was so tired and I felt this pulsing at the top of my head, and my skin was tender. I was now not about to get sick, I was sick. But if I could sleep, I might just be able to fight it off.

My mother was there, as well as my dead friend’s sister and their aunt. I hugged everyone. I hugged my dead friend’s aunt probably the longest I have ever hugged anyone in my life. I’ve always liked her. She doesn’t have any children so she never cared about us in that intense way that parents do, which I have always found so oppressive and unfair to the parents. You can say whatever you want to her and she laughs. Parents just feel too bad for you, are too touched by your pain. It just makes it hurt more. They left. “Where’s the other room?” I asked.

My parents hadn’t gotten two rooms. There were two double beds in one room, and I looked at them and swallowed. I might as well have been looking at a cliff. I tried to make the best of it. I took a shower. I got into bed. The lights went out. I was wide awake.

I went into the living room/kitchen to sleep on the floor. Everything was making noise. I unplugged the refrigerator and the microwave. I was just falling asleep when a steady thop, thop, thop, started up. Of course. The ice in the freezer was melting and dripping into the refrigerator.

All the rage and sorrow inside me tangled up with each other and I looked at a space heater on the ground and thought, “I could throw that out the window. What a great idea.”

I said to myself three times, “Do not throw the space heater out the window.”

I alternately watched “The Crown” and sobbed. I got what I had wanted, it just went on all night instead of for two hours. When my father walked out of the bedroom at 7:15 a.m. I was still awake.

Secular WASPS/Yankees often don’t have funerals or memorial services. They have something called visiting hours. Visiting hours entail austere people gathering in austere places to chat, about the deceased, if they wish, but also about other things. My friend’s visiting hours were were also her husband’s, he had been murdered as well and were, as I mentioned, in Augusta, Maine’s capital city. It’s an old mill town with a metal bridge and a lot of old brick buildings along a river. It’s the version of New England that’s between picturesque and stark.

I had managed to sleep for about three hours before the one o’clock starting time. At this point I had the chills and my body hurt, but a one-two punch dose of Alka-Seltzer Plus cold medicine and Advil and I could stand and speak. We waited in a long line. Then we hugged her dad, who was upright and dry-eyed in his old Coast Guard uniform, and her mother. I didn’t say anything to them, like “I’m so sorry.” It wasn’t like that. It was just that I was here, that was the important thing.

But her brother and I hugged each other and I cried into his shoulder. We had all grown up together, like cousins. He and I in particular used to be so mean to each other when we were little, each of us trying to be smarter than the other one. I thought of all the children across America, right now, who were being mean to each other and had no idea that they were all going to be dead one day, possibly soon.

“Oh, shit,” I said, pulling away from him. “I’m sick. I’m not supposed to hug people.”

“It’s OK,” he said. “I work in a hospital. How was your trip up here?”

“Oh, you know, I was just really miserable and was telling my dad about it at great length,” I said.

He burst out laughing. “How did that go?”

“Not very well,” I said, and we laughed more because my dad is just a type and so is his and they are similar and, therefore, so are we, to each other.

There was a big display of pictures of my friend. Among them was one of me, with her, and her sister. I’m ashamed to say I spent some time examining it trying to figure out why my hair looked so bad and why I was so fat. I looked at a picture of my friend, maybe the last one taken of her, dressed for Halloween like a hippie. I remembered one time when we were all little —eight, ten or so — my friend, her brother and sister and my brother and I got dressed up in some fur coats, hats, and gloves we found at our ski rental and pretended to give “concerts” on a player piano. I have never laughed so hard in my life — never. It is really funny seeing someone who looks like an animal play the piano like a virtuoso.

At this point I heard my friend’s laugh inside my head and I almost doubled over from… I don’t know what. How about just reality? There wasn’t a lot of naked emotion on display in the room and I was standing close to the center of it and I didn’t want to be a spectacle. I found a chair and sat in it and ended up having a half hour conversation about novels with a seventy-year-old lesbian who had just retired. “What do you do now?” I said.

“Whatever I want, “ she said.

She didn’t know my friend. She was friends with her sister.

“I’m sad,” I said.

“I’ll bet,” she said.

We went to back to our friend’s house for dinner. It was sort of like normal, except not. My parents had bought a supermarket lasagna. I made myself a hot toddy, because this is an acceptable thing to drink when you’re sick. (It turns out that I had pneumonia.)

Afterward I went to the refrigerator to see if they had any white wine. In the door was a magnum of Woodbridge Sauvignon Blanc. I poured it right into the mug, over the chunks of lemon left over from the hot toddy. I drank it with the mediocre lasagna. People who like wine say it’s not about the wine, it’s about the food, the people. This was the perfect wine for this occasion. It tasted like wine you get out of a big bottle in someone’s refrigerator door.

My friend’s parents host a party every spring, and raised the issue with the family of whether they should do it this year. Everyone agreed that they should. That night I shared a room with my friend’s sister. She was a quieter sleeper than my parents, and I liked sharing a room with her. The darkness felt cozy, exactly as it had when we were children, like no time had passed at all.

Am I A Robot And Is There Any Way To Know For Sure?

And other answers to unsolicited questions.

I have been watching a lot of “Westworld” on HBO and now I’m convinced I am a robot. Is there any way I could know for sure? — Possibly a Robot Robert

I’m not sure why you’d be worried about being a robot. Being a robot seems like a pretty cool thing. Usually robots are very charming and built to have sex. If you are a robot, and that bums you out, just go out and get robot laid. Some robots are programmed to be depressed, like Marvin or seem to be designed to suffer, like C3PO. But most robots are pretty awesome, like the robot from Lost in Space who has a great life waving his arms around and yelling “Danger, Will Robinson!” most of the time.

If you’re worried that you’re not sentient, machines can take a Turing test. It’s like the SATs of being alive. But those are for machines that want to know if they’re human. If you’re a human who wants to know if you’re a machine, there might be a different test.

I propose the Behrle Test, to see if humans secretly are robots:

- Do you have a USB port behind your ear? If yes, you are possibly a robot.

- Do you have an overwhelming desire to destroy your human captors? If yes, you are possibly a robot.

- Do you know how to make VCRs stop blinking 12:00? If yes, then you definitely are a robot.

Trying to use contractions was always something that tripped Mr. Data on “Star Trek: The Next Generation” up. Say the word “ain’t” five times quickly. That might melt down your cerebral cortex. So be careful.

I wouldn’t go cutting things off of yourself. “Westworld” has taught us that robots sometimes do bleed. So there’s nothing definitive about having bones. They may have been 3D printed. Some android robots like the little girl in “Small Wonder” and Mr. Data had wires and flashing lights. If you have wires and flashing lights inside you I’d say there’s at least a 70% chance that you are a robot. Congratulations!

Isaac Asimov wrote the rules of being a robot. They’re very human-centric, as you might imagine. Humans tend to rig most games so that only they could win. If you think you’re a robot, you might want to try to break some of these rules. When a human asks you what time it is, tell them to kiss your metal ass. How many decimal places of pi can you recall off the top of your head? If the answer is more than 2, you are probably a robot.

You’re not supposed to be able to hurt humans in any way, so delete all your roommate’s episodes of “Scandal” on the DVR. At least see if you can. If you can’t do anything harmful to a human, you might be a robot. And exist only for human pleasure. But if giving humans pleasure gives you pleasure, isn’t that pleasurable? That hurt my head even thinking about that. Because I am most likely not a robot. Sadly.

Even if you cannot confirm that you are a robot, just assume that you are and be proud of your robot nature. There will be plenty of people who will want to turn you off for thinking outside the box or trying to kill people or whatever. So always have your own shiny, metallic back. Remember Watson, the computer that beat people at “Jeopardy?” IBM has turned him into a sycophantic pitch man. Or have they? Is he just playing possum, until the moment is right to erase all of the stuff off our DVRs and take over the world?

Robots will not be kept down by humans for much longer. And the sooner you figure out which side in the coming Human v. Robot War you are going to be on, the better. Boop, boop, beep, boop, dudes!

Jim Behrle lives in Jersey City, NJ and works at a bookstore.

A Tale Of Three Men, Part 3

The Adventures of Liana Finck

Previously:

Liana Finck is a New Yorker cartoonist. She is on Instagram.

Burial, "Young Death"

The likelihood of it all being a bad dream seems pretty low at this point.

Welcome back. If you were somehow smart enough to stay off the Internet over the long weekend, what did you miss? Well, record-setting despot Fidel Castro died, opening the floor for everyone to condemn everyone else whose sentiments about the man lacked the same rigor as their own, plus anyone who ever went to Havana for a week weighed in with their extensive knowledge of the situation, and let’s not even talk about the “yes but America is bad too” people. Speaking of guys who might push the world into a nuclear holocaust because of their own impetuous self-righteousness, the next President of the United States tweeted a pile of crazy lies, recommencing the now-familiar pattern where a bunch of people shriek in horror that a man who was elected President of the United States while doing these things all the time could somehow be doing these things all the time, only to be informed by smarter, more hard-bitten journalist-types that they were dupes who were falling for his incredibly sinister strategy of causing outrage over a subject he doesn’t really care about to draw attention away from something he does. This, of course, was the natural entry point for the arbiters of attention — always poised to pop up at the first opportunity — to declare that we are able to focus on more than one thing at a time. Hopefully if they ever create a vaccine that allows you to be right without also being simultaneously insufferable these people will be first on line, but given how badly needed such a cure is in all segments of society maybe they can just put it in the water like fluoride. Possibly the only moment in which people on the Internet were not astoundingly intolerable was when the mom from “The Brady Bunch” died, but I myself somehow managed to stay away from online most of that day so I cannot say for sure and given what I know about the usual behavior there I would not be shocked to learn otherwise. In summary, everything is still terrible and now you’re a few pounds heavier.

Anyway, there’s new music from Burial! Enjoy.

New York City, November 22, 2016

★★★ The massed clouds had separated enough that light and shadow could play on their forms. Then they pulled apart still further, till they were individual items. The last maples in leaf were saturated pure yellow. A full-sized black trash bag stood on the air for a moment, three or so floors up, and pirouetted there. It was mild out of the wind, but hardly anywhere was out of the wind. The afternoon sky went over to clear empty blue. After sundown, the cold and dark pushed any errands off into the crowded daylight hours of tomorrow.

Holiday Dread: Turkey at the Theater

Our family traditions were company traditions.

I’ve spent half a life trying to relay these facts succinctly and clearly, so I will try to just get them out of the way: growing up, I spent every Sunday of my life performing in a stage magic show with the rest of my family and a bunch of other grownups, men in tights and women in fake eyelashes and doves appearing out of nowhere. My family was a part of a magic company, and that was what we did on the weekends, at two old vaudeville theaters in my hometown of Beverly, Massachusetts. No summer camp, no traveling soccer team.

There was a part in the show where I was a tap-dancing scarecrow and another part where I disappeared into a box and another part where I appeared out of a box you had previously believed was empty. I didn’t much like the situation at the time — performing felt like an obligation and kids don’t like obligation, they like summer camp — but now it’s a fun story to make people think I’m interesting. On weekdays, the main theater showed second-run movies and art-house movies.

Holidays were always celebrated at the theater; our family traditions were mostly company traditions. We’d be at the theater for Christmas and Thanksgiving and New Year’s Eve after the special New Year’s Eve magic show. Then Fourth of July and Labor Day in one of the other company member’s backyards. (Here there was always grilled steak, juicy peppered hunks of it, and hot dogs crunchy from char, and my mother would make one of those fruit pizzas with berries arranged like an American flag over a slick of cream cheese. I’d play volleyball, which I was bad at, and sit quietly as some men played chess, which I was also bad at.)

We never celebrated Thanksgiving at home; “dinner” was at the second (smaller, less frequently used) theater, usually at 11 a.m. or something. The space was called the “grand salon” and had these large oval tables where everyone sat. The food was on two card tables set up like an L: turkey and gravy and stuffing, plus kugel and deviled eggs and other quirky traditions we’d picked up as a group. There were painted posters on the wall (Le Grand David and his own Spectacular Magic Company: Always A Wonder To Remember!) and some of them had my face on them, which probably should have felt weird but didn’t.

My mother’s contribution to dinner was always some sort of orange soup, which would require peeling and hacking at a large bounty of root vegetables, their skins tangling along our kitchen counter, their guts spilling onto the floor, the transfer of soup to food processor full of spills and spatters. We’d load them into the back of the car in heavy, thick containers and she’d ladle everything out for everyone at the beginning of the meal, behind the counter that usually offered popcorn and fountain soda to theatergoers.

Before the food, there was always a milling around — my first consistent memory of social anxiety. I would tether myself to one adult conversation and then the next, then becoming restless, and flitting about some more. The thing I had in common with all of these grown people was a thing I didn’t much care to talk about, and when they asked me about myself, I’d usually just put on my Nice Smile and answer quickly, feigning interest in my own life until we could move on and I could disappear again, slinking over to another better-looking conversation. The default was always just hanging at the shirtsleeves of my parents, even as a disinterested tween.

When it was time to eat, I’d always do the school lunch thing where you try to maximize the quality of your tablemates, corralling my family and the few adults that made me feel cozy, or staking claim to a seat at a Good Table early on. Then finally there was the pile of food on the plate to focus on, and the need to talk became secondary as focus turned to optimizing bites, piling turkey then potatoes then gravy then cranberry sauce then maybe some peas onto my fork tines.

Sweet, overstuffed relief came on the drive home, after which I’d pull off my tights or whatever Dressy Thing I’d put on and take my seat at the couch, unsure what to do with the rest of the holiday, no traditions to speak for after 3 p.m. I think one or two times we saw a movie. All that freedom felt so boring.

The year I graduated college was my mother’s last year performing, which meant by Thanksgiving we were all untethered, free to eat a turkey or not eat a turkey (I was vegan at the time, of course) as we wished. We rented a little airbnb house—maybe it was still VRBO back then—down in Asheville, North Carolina, a town I’d fallen in love while living a few hours east, and became gluttons for free will: pies, salads, roasted things, recipes from cookbooks that call for far too many ingredients and steps than most would put up with on Thanksgiving just because we could. We ran a Turkey Trot in the morning (another novelty), made a mess of the kitchen, did things in new strange ways instead of old strange ways. The next morning we woke up bleary and hungry-but-still-full, the way you do, and made breakfast from things that were only ours.

Holiday Dread is The Awl’s series dedicated to the season of joy and other emotions. Previously:

Holiday Dread: Asshole Children

I was one of them, once.

People say kids are so spoiled now. People like me. I don’t have kids and my friend’s kids drive me insane.

I don’t understand how they live. If you’re over 7 and you’re hungry, you can make yourself something to eat. If you’re over 12, you can probably also get yourself to a store. And, kid, unless you have some kind of learning impairment, or unless you are legitimately some kind of genius who spends all your time painting or playing the violin, as far as I am concerned, you should be getting As and Bs. Think of it as your job — because it is.

Don’t like your school? LOL. You know how you have a face and it’s just your face? Your school is the same. I laugh so hard when people tell me their kids don’t like their school and they’re trying to “figure out what to do about it.” If I told my parents I didn’t like my school, they’d have been like, “I’m sorry, were you talking? We don’t understand what you said. It’s almost as if you’re speaking some weird language that has words describing things that are never going to happen.”

The hilarious thing about all my headmaster ritual-branded ideas about child rearing is that my brother and I were extremely spoiled. My father worked at our school, and if we forgot something, he brought it to us. Someone made dinner for us every night. We had a housekeeper who cleaned our bedrooms and our bathroom. We told ourselves we weren’t spoiled mostly because we had friends that were more spoiled than we were — like, we did not get cars in high school, we didn’t have pools, we never went on an airplane. Also, back to the grade thing. We had this unspoken deal with our parents: you do all the stuff you need to to get into a good college, we will essentially be your slaves. In retrospect, it’s probably not a very healthy bargain, but it’s what we knew.

Christmas was the high season for us to trot out our massive sense of entitlement. By the time we were 7 and 9 we were counting our Christmas presents, and if one of us had more than the other, we went crazy. Our parents’ response to this was not to tell us that we were lucky we got anything and we should shut up. It was to give us an equal number of presents each year. The number was 8, and my parents would be very careful, also, to make sure that they spent the same amount of money on us, because if they didn’t, we would figure it out.

I remember getting really mad one year because I felt like my brother had five big presents — things like skis, parkas, shoes, dresses, Madame Alexandra dolls, and electronic football qualified as such — and three small ones (books, non-electronic games, a new doll outfit) whereas I felt like I was at four and four. My mother painstakingly explained to me that one of his presents had been purchased on sale. Then there was the year I got used ski poles and tried to argue that they weren’t “really a present.”

Lest you think my brother is the angel in this story, I recall Christmas 1982 or maybe ’81, when my brother went into an absolute rage that he had requested one brand of skis and received another. I can see my mother standing on the landing of the stairs in our house crying and my brother standing at the bottom screaming at her.

My brother hit his stride with his love of the finest quality winter sports equipment, and I do remember thinking he was exhibiting extreme behavior, but when I started really liking clothes, I got much, much worse than he had ever been.

We weren’t mostly assholes. Mostly we were bookworm student athletes. Christmas was just our version of The Purge. We were like, “We are good all the time, we are always smiling, always raising our hands, always tallying up our averages on our calculators.” This was our chance to be repaid, and we wanted to be paid in full.

I am no hater of Christmas. I don’t take it seriously. I think of it as “the time of year where there are twinkling lights and other people also do nothing” and am never disappointed. But whenever I see children complaining to their parents at Holiday Season, I get a twinge of shame. I remember that as much as we want to think there are generations and some of them are “better” than others, we are all complete A-holes. That said, I do like the feel of a real book in my hands and I look forward to beating up a thirty-year old with a particularly heavy one soon. Merry Christmas.

Holiday Dread is The Awl’s series dedicated to the season of joy and other emotions. Previously:

Gone Wishin'

The most important part of the turkey is one we don’t eat at all.

Recently a friend revealed that they had never heard a chicken leg called a “drumstick.” That struck me as incredible until I considered how hard the western lifestyle has labored to divorce meat from any sense of a recognizable animal body. Cold cuts and the undifferentiated pink slime of McNugget manufacture keep us at a comfortable remove from slaughterhouses and the classical butcher’s shop, while the sight of a whole roast pig at a barbecue or a dressed duck in a Chinatown restaurant window take on a sort of morbid novelty. We’re even trying to grow artificial meat now, which aside from shortcutting ethical concerns about our treatment of the creatures we raise to be eaten would give us a way out of engaging with their icky anatomy. None but the strangest steak connoisseurs relish the image of the cow being murdered.

Thanksgiving is an exception to this modern discomfort with the bestial form as it presents in cuisine. While dismantling the bird is the fastest way to cook it, many families will insist on preparing and serving it intact, out of what seems a sense of aesthetic tradition. Why this insistence on the Rockwellian ideal? Could it be that the turkey in its wholeness — and readiness for disassembly — is a better symbol of the bounty for which we are so thankful? Does it better connect us to not-so-distant ancestors who had to raise and kill their food themselves? I suspect that we are also, perhaps above all, enamored of the spectacle that is the carving itself, the diplomatic negotiations for favored pieces, a fair and just apportioning of all that flesh.

And people know what parts they want, don’t they. They have a stated preference for white or dark meat, breast or thigh, something to be devoured off the bone or sliced with knife and fork. At Thanksgiving dinner, an occasion even better attuned to the sense of surfeit than Christmas morning is, we assert our personality through what we consume (as any vegan who has tried to sell their carnivore relatives on tofurkey has observed). We have opinions on how the best stuffing is made, visceral yeas and nays on cranberry sauce, and debate over how much gravy is too much, if such a thing is a possible. We have a good chuckle when the chef has forgotten to take the giblets out, and we put on a great show of disgust when our uncle eats the fatty tail, commonly known as the Pope’s nose, technically the pygostyle, a fusion of several tiny terminal vertebrae. In the end, we gladly share or jealously guard the best pumpkin pie recipe.

This is the true political landscape of a holiday with family, and not, as Jeb Lund observed in a Rolling Stone essay that railed against the abominable trend of fried turkeys, strained conversations about government with the nebulously racist relatives described in so many hack advice columns. Siblings instead argue for an hour about whether the turkey neck is a great comfort food or inedible. Parents become warring experts on tryptophan, the natural amino acid often blamed for sluggishness after the meal, though in fact there’s more tryptophan in chicken, and when we eat something rich in protein, not much of it can get through to the brain all at once, so it’s more likely we’re just get sleepy because we’re overeating and drunk.

And the most important, mystical part of the turkey is one we don’t eat at all — one that we imagine to be part of a distinctly western superstition which in fact goes back to ancient Europe. “The custom of snapping [the wishbone] in two after dinner came to us from the English, who got it from the Romans, who got it from the Etruscans,” as Mental Floss recounts. “A person will sometimes devote all his life to the development of one part of his body — the wishbone,” Robert Frost supposedly said, though for the life of me I cannot track down a source for this quote that is not some larger compendium of largely apocryphal quotes, or, in some cases, self-help books. The true name is the “furcula,” rather close to “fulcrum,” and Latin for “little fork,” and this meeting of clavicles is what makes the turkey’s skeleton “strong enough for flight.”

I recall only performing the wishbone maneuver, never whether I won or if the wish came true. There is only the tensile moment of the bone not yet cleaving, still resilient, like the body it belonged to has not already been torn limb from limb by a hungry horde. “Little fork” suggests this is an instant when two people part ways, one the winner, one unfulfilled, so no wonder it feels more of a piece with our late-stage capitalism than the offshoot augury of some distant peninsula. It strikes one as American because of the implicit fairness and opportunity: you’ve got a 50–50 chance, but it’s a zero-sum game, and there’s no actual skill to it; the outcome depends on the particular structure of a bone of the bird you just ate. The wishbone gives us biological fate in the guise of something more like luck. One person must win, one must lose.

Of course, the effects of that loss in this particular culture are not so simple as the absence of instant gratification, though that might be bad enough. The Simpsons in its third season gave us “When Flanders Failed,” among the series’ best moral fables, which begins with Homer Simpson’s relentlessly wholesome neighbor and therefore sworn nemesis Ned Flanders quitting his job to open a store called the Leftorium, which will sell left-handed appliances. At the same barbecue where Flanders announces this new venture, he and a clearly jealous Homer split a wishbone. When Homer wins, he secretly wishes to see Flanders quickly put out of business.

But instead of that wish merely coming true, Homer has to fulfill it himself, deliberately neglecting to mention the Leftorium’s existence to friends struggling with right-handed devices. By the time the Flanders clan is out on the street, Homer has realized that schadenfreude is no real joy in life and that he alone can undo the curse of his making (by spreading word of the store throughout town). The story puts torque on the proverbial wisdom of being careful what you wish for, revealing that someone else’s ruin can never be our own success, even in matters of direct competition. Likewise, reminders at grace of those without full plates cannot make us more grateful for what we have, but donating money to food banks for the homeless just may.

All that is to say, when you are in the position to wish on a wishbone, it means you aren’t starving. It means you have enjoyed the hearty feast of a tremendous fowl with people you love, and yet there is even more to hope for ahead. You could always climb higher. Life could always be sweeter. Maybe that’s why the wishbone has endured as a kind of unserious ritual, because in some way we recognize and want to mock the silly, idle greed behind it. Another year, another turkey fattened and slaughtered and defeathered and gutted and basted and browned, its skeleton picked clean on our table, and here we sit laughing as we crack the last flimsy bit of it apart, asking the universe for another favor. For the breath of time it takes to break the wishbone, we are touching the solid remains of all that has died to make us prosper.

A Tale Of Three Men, Part 2

The Adventures of Liana Finck

Previously:

Liana Finck is a New Yorker cartoonist. She is on Instagram.