New York City, November 30, 2016

★ The rain had paused, leaving pulpy leaves and pulpy printed leaflets flattened to the sidewalk. It was urgent to find something to do in the break, even if it was just going the extra distance for coffee. Soon enough after, it was visibly wetter outside, and soon enough after that it was pouring hard enough that peripheral vision could notice it. The morning’s invitation had been rescinded; even the short half block out to Broadway became an insuperable distance, the corner seemingly receding as feet splashed toward it. After nightfall it took a moment to find the boundary between the wet plaza of Lincoln Center and the reflecting pool in it.

The Most Regionally Authentic Details In 'Manchester by the Sea'

(Otherwise the movie is as crappy and as pretty as it should be.)

Last night some friends and I saw the movie Manchester By the Sea. Have you seen the trailer? It jerks itself off pretty hard.

“Perfect!” — Casey Affleck’s assistant

“The best film I’ve ever seen.” — Ben Affleck’s third grade teacher Lorraine

Just kidding, it quotes the press and the movie got a lot of compliments.

It’s a movie about a Boston-area man who, after losing his brother, finds out that his teenage nephew has been left in his care. Could be something! Potentially charming! But after an entire 20th century’s worth of art, I’m generally fatigued at the prospect of a project that asks us to summon sympathy for white men in pain—especially when that white man is Casey Affleck. Nothing about this movie moved the needle for me interest-wise. Yet somehow, the trailer did its job.

We had two back-to-back rainy days in New York this week, and after the second one I found myself thinking, “The showbusiness industry really seems to like this movie. I should see it so I can know what’s happening at the Oscars.” Isn’t that fucked up? I pulled the trigger and bought a ticket.

The movie is fine. I don’t know that I’d jump right to “miraculous” or even “terrific,” but hey. It has a beginning, a middle, an end. There are stakes. What it did best, in my unnecessarily focused opinion, was present a very vivd world for these people to inhabit. At one point a character needs to be slid into the back of an ambulance on a gurney and the accordion-style legs have trouble collapsing. It happens during an otherwise serious scene and ends up being funny because it’s embarrassing and sad and a little tonally-off. New England. My home.

As I see it, here are the most regionally authentic details:

- Bringing a six pack of Narragansett to a funeral reception.

- Telling your nephew that Misery Island is where you and your wife got married.

- Aboveground power lines cutting through a lowkey gorgeous view that no one ever remarks on at all times.

- The amount of time spent in an old Jeep Cherokee*.

- The amount of sound made by that old Jeep Cherokee’s crappy engine every time it started.

- Not being able to bury your brother til Spring because the ground is frozen and the other graves in the graveyard are patriotic artifacts.

- Patty’s girlfriend’s bedsheets a) being mixed and matched, but more importantly b) featuring a green Tommy Hilfiger fitted sheet that was available in greater New England T.J. Maxx locations like four years ago (I know this because my sister bought and still has the whole set).

- Having a stack of lobster pots outside your front door.

- Crying with the game on.

- Keeping three framed photos on any given surface, minimum.

Inauthentic:

- Everyone is thin and hot.

A solid showing, as I saw it. I’m not very charmed by watching drunk sadboys schlump around in cinema here in Trump’s America, but it is nice to watch the particulars of a place be really cared for and shined up and held out to us like that.

______

*Shouts to the god Caitie Delaney.

Prokofiev's 'Romeo and Juliet' Is Better Than Shakespeare's

Classical Music Hour with Fran

Fine, I get it: it’s the holiday season and you want a ballet. I’m sorry I won’t be writing about The Nutcracker, you’ll be fine, trust me, but I do sympathize. There’s something inherently winter-ish about listening to ballet music. (Google search: “is there a good ballet about summer?” Results: “Top ten ballet summer immersives.” Um, nvm.) Beyond that, listening to a ballet is an extremely chill thing to do. I always find I do my best driving, for example, listening to a musical or a ballet because the pieces, for the most part, are fairly short and it moves quickly with a semblance of a story that’s coherent even if you don’t know what happening.

So here: let’s talk about Sergei Prokofiev’s Romeo and Juliet ballet. It’s a blast. And I know it’s easy to rag on Romeo and Juliet, just conceptually, because it is [extremely English-major voice] not one of Shakespeare’s best and [extremely I-delivered-a-paper-on-Shakespeare-at-a-conference-in-Western-Michigan once voice] not all that deserving of the attention it’s received in pop culture over the years. That said, the Baz Luhrmann version is good because it’s from back when Leonardo DiCaprio was good, and the Prokofiev ballet is, if you can believe it, better than that. Namely because we don’t deserve to give these fifteenth-century teens from Verona the height of cinematic drama for their love; we deserve to give them the gift of dance.

Prokofiev was an early twentieth-century composer, spending most of his training and schooling at the St. Petersburg Conservatory during World War I. It was in his early years, immediately after finishing up at the conservatory, that Prokofiev became interested in ballets. He worked closely with a man named Sergei (just two friends, both named Sergei) Diaghilev, a member of the Russian aristocracy, who often helped to produce and organize ballets. The only reason that I’m including this thing about Other Sergei is because it was Other Sergei who introduced Prokofiev to Léonide Massine (OF ALL FREAKING PEOPLE) to collaborate on his early works.

Not unlike our pal Dvořák, Prokofiev spent a significant amount of time in the United States, both in New York and in Chicago. Prokofiev, however, was less “trying to discover American music” and more was, um, “trying to get out of Russia during the Revolution.” It was on his last visit to Chicago, in fact, that he debuted a couple of scenes from Romeo and Juliet, which he would go on to finish back in Russia.

There are two ways you can listen to Romeo and Juliet. The first is to listen to the full ballet. I like the London Symphony Orchestra recording conducted by André Previn from 1987. It’s two and a half hours long, but keep in mind it moves quickly and you can skip around if you so desire. Or you can listen to an orchestral suite arrangement of it; I’m partial to the Second Suite, and this recording by the Royal Scottish National Orchestra is pretty good. I won’t walk you through the entirety of a two and a half hour ballet, but I can show you some of my favorite parts.

Masks, for example, is perhaps where the ballet really gets going for me. This is the scene in which Romeo and Mercutio show up, in costume, at the Capulet party (cue Leonardo DiCaprio, fish tank, Claire Danes, etc.). We played the Romeo and Juliet suite in college, which includes a refrain from Masks, and I had to play tambourine for it. The whole percussion section for this piece has a back and forth between the tambourine and the snare drum and the triangle. I felt like a profound dumbass the whole time playing it, but the overall sound of “teen costume party” works very well. In any sort of ballet, it’s best to imagine that any instrument’s solo is a substitute for dialogue, so the trumpet solo here is very funny to me as well; it screams, “Hey, there’s girls at this party!”

The next part, and one that I think you’ll definitely recognize is, Dance of the Knights, which is also known as Montagues and Capulets. It’s got this really heavy, brassy sound to it. It’s probably the most classical music-sounding example of “men fighting” or “men dancing” or “men arguing.” This piece is everywhere in pop culture, ranging from its use as walk-on music for Iron Maiden, the theme for both the British and UK version of The Apprentice (I’m sorry for even mentioning this show, I really am, but it felt too prominent to ignore), and most importantly: the theme for the Russians in Civilization V.

And lastly, a little part that I just love, really and wholeheartedly, because it’s upbeat and kooky and fun is the Mercutio theme. It’s everything you want: entrance music for the main guy’s friend: XYLOPHONE, a jaunty little melody. If this isn’t “Enter: Best Friend” music, I don’t know what is. I listened to this particular section when I was making my bed this weekend, and I swear I did it just a little bit faster. But again: these are just tastes. By the time you’ve listened through Mercutio, you’ve still got just under two hours left. If you don’t know how this one ends, well, it’s not my place to spoil it for you.

Fran Hoepfner is a writer from Chicago. You can find a corresponding playlist for all of the pieces discussed in this column here.

Grow Your Own Penicillium

Odd Lots: Curious Objects Up At Auction

A cup o’ mold, the key to Oscar Wilde’s prison cell, and a Tim Burton art tile

Lot 1: Nobel Prize-Winning Penicillin Mold

This greenish glob is world famous — it is one of the original penicillin molds that tipped off Scottish biologist Alexander Fleming to its antibiotic properties.

The discovery was accidental. In 1928, Fleming had been studying Staphylococcus. When he left the lab for a two-week vacation, it seems he forgot to place the petri dishes in the incubator. Instead, the samples were left out, and a Penicillium mold spore grew alongside the bacteria. Upon his return he observed that the mold seemed to inhibit or prevent the Staph’s development. It wasn’t until a decade later that Howard Florey and Ernst Chain continued the research that would give us the first mainstream antibiotic (goodbye, syphilis!), for which Fleming, Florey, and Ernst shared the Nobel Prize in 1945.

Preserved between two pieces of glass and signed Alexander Fleming / 1954 on its underside, Fleming gifted this 1928 culture to his neighbor, Mr. Bax, who had scared away some burglars from Fleming’s house. An accompanying letter — written on March 8, 1955, just three days before his death — expresses Fleming’s thanks.

The question is: will Americans bid more for mold than Brits? At the upcoming sale, scheduled on December 7 in New York, Bonhams expects the blob to reach $10,000–15,000. It sold at a smaller UK auction just over a year ago for the equivalent of $7,154. Game on.

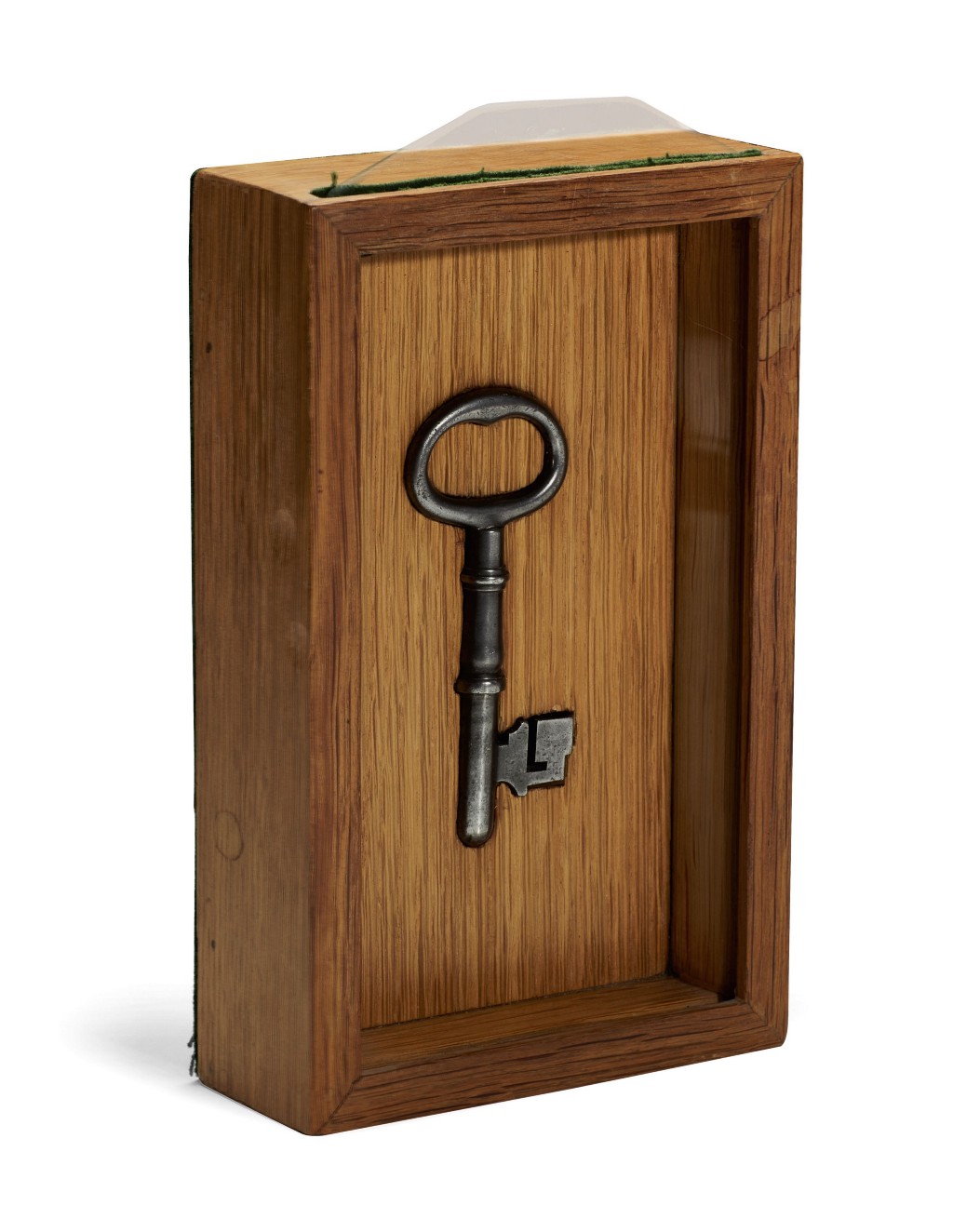

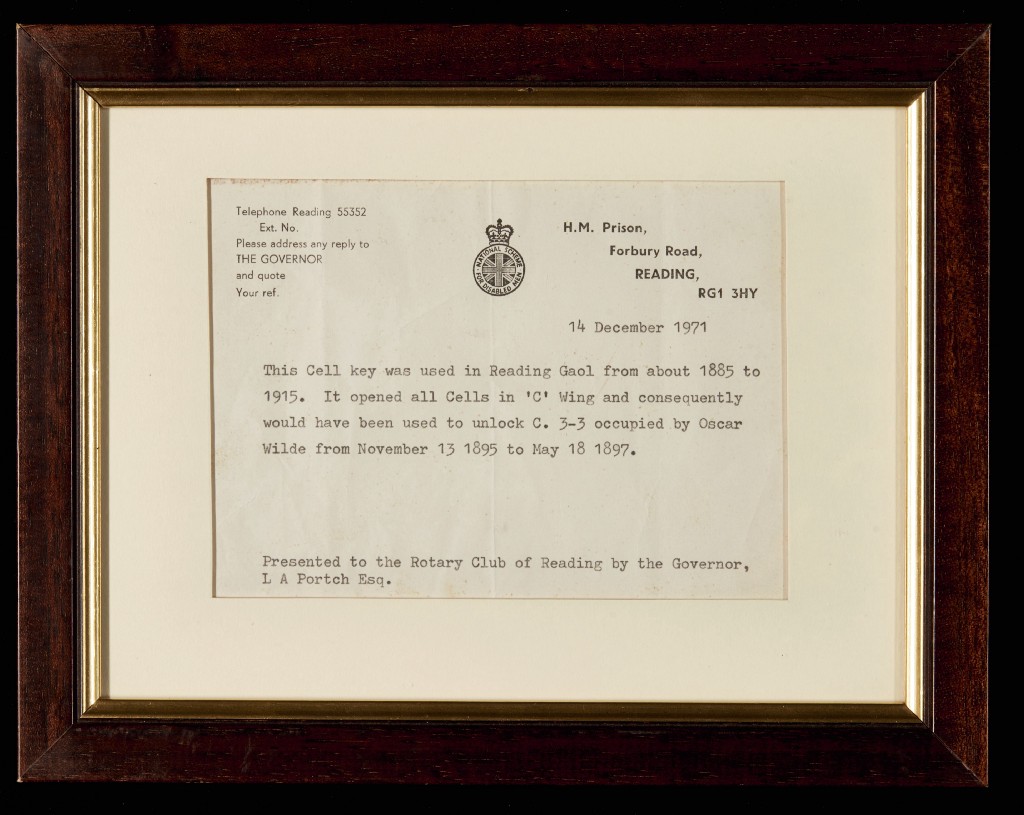

Lot: 2: Key To Reading Gaol

In 1895, Oscar Wilde was sentenced to two years hard labor at Reading Goal — a prison that now celebrates its connection to him — for the “gross indecency” of loving another man. Upon his release, Wilde published The Ballad of Reading Gaol, a long-form poem about the brutality of incarceration, a stanza of which reads:

So they kept us close till nigh on noon,

And then they rang the bell,

And the Warders with their jingling keys

Opened each listening cell,

And down the iron stair we tramped,

Each from his separate Hell.

One of those “jingling keys” is slated for auction in London on December 13. This nearly four inch-long metal key was, according to accompanying paperwork issued by a later governor of HM Prison, Reading, used to unlock all of the cells in ‘C’ wing from about 1885 until 1915, well within the right time period. And Wilde was indeed confined to cell block C, landing 3, cell 3 — he first published his Ballad under the pseudonym C. 3. 3.

The current owner’s father purchased the key, now mounted in a wooden presentation box, in 1971 at a Rotary Club auction. One imagines him winning it for a fiver. But those days are long gone. Sotheby’s estimates it will reach as high as £6,000.

Lot 3: Tim Burton’s Hand-Painted Crafts

Most of us think of Tim Burton as a film director and/or producer of macabre favorites like Beetlejuice, Edward Scissorhands, Frankenweenie, Corpse Bride, and Miss Peregrine’s Home for Peculiar Children. But the guy also draws, paints, and makes puppets, and he’s exhibited this work at MoMA and LACMA.

Apparently Burton also hand-paints ceramic tiles. Pictured here a whimsical skull and crossbones tile that he painted circa 1993/pre-Pinterest. If its stitched mouth and vacant eyes evoke the face of Jack Skellington from his holiday mash-up, The Nightmare Before Christmas, there’s good reason. As Burton once said of the ghoulish character, “That was just a doodle I kept drawing over and over and over for no apparent reason.”

As a piece of original Burton artwork, this ceramic tile is expected to realize $3,000–5,000 at auction in California on December 9. The tile was obtained, according to the auctioneer, “in 2005 from Burton’s one-time fiancée, Lisa Marie.”

Rebecca Rego Barry is the author of Rare Books Uncovered: True Stories of Fantastic Finds in Unlikely Places.

A Poem by Laura Eve Engel

Burden of Belonging

Today we are grieving our nation’s

peaceful transition of power

what we are really saying is we’re scared

about how many of us

choose not to recognize

we depend on one another

to stay whole and unhurt

I am responsible for you

here hold my heart

why am I glad for this burden

of belonging when others

are not

to whom do some of us

not belong

who hurt some of us so

but here they come again

this history of men

who when they were healthy

refused the hearts of their neighbors

until they were weak from it

now their suffering punches up

out of the rich soil

thorny and asserting

you are not suffering I am

suffering

something inside the weed

urges it to need

and kill the garden

to offer and offer itself

until it’s choked all

but its own color out

where it was never written

not all suffering is created equal

and not all need

vigilance against the new appearance

of old growth

has never been enough

we must rewrite the ground

Laura Eve Engel’s work can be found in Boston Review, PEN America, Tin House and elsewhere. She is a recipient of fellowships from the Helene Wurlitzer Foundation, the Provincetown Fine Arts Work Center, and the Wisconsin Institute for Creative Writing.

The Poetry Section is edited by Mark Bibbins.

Aos, "Trance On 99"

November finally ended, now what?

I cannot remember a longer November, and I’ve lived through so many of them. I would say something about how happy I am to be out of it but knowing what December is like, and having a sense of how slowly things are going to go from now on, it would be foolish to express joy about anything. December might last forever. The only good thing about that is the plans you make for the new year to avoid getting together during the holiday season will never come due, but that seems like a high price to pay for an endless season of pretending to smile at holiday parties, sweating under your coat on the train and having to hear Joni Mitchell’s “River” at CVS while all you’re trying to do is pick up an acid reducer for the heartburn you experience every second now. As happy as I am to see November go there is a not inconsiderable part of me that is concerned we will in future months look back at it as a relatively placid and pleasant part of our lives compared to what we are living with in the present. I guess we’ll find out.

Anyway, here is seven minutes that will hopefully offer a small amount of soothing for your soul. Enjoy. [Via]

New York City, November 29, 2016

★ The rain was steady but light enough at first for the five-year-old to re-furl his umbrella, keep his hood down, and veer around and past the plodding umbrella-burdened other children. The classes were still lining up in the yard, the bad-weather plans uninvoked. It was wet but not raw. At noon the rain was coming heavily, sending the gutter flow sprawling into the roadway. The lights mirrored in the sidewalk under the deep gray gave more than a passing sense that it was already night. Outside the library windows in the later afternoon passing taxis threw up arcs of spray. It rained harder still on the short walk to the cafe, and from there the rain outside came in thinner and thicker spells while pedestrians went by in the slowly deepening gloom, till a waiter put wavering candles out on the counter and tables.

The Deal

A gift in verse

I have thoughts about Bob Dylan

and how Bernie would have won

and how tweets are a distraction

and the damage P.C.’s done

I’ve opinions about “Westworld”

and about the phrase “alt-right”

I’ll give you takes on “Gilmore Girls”

to last you through the night

Should Hillary put makeup on?

I’ll answer loud and clear

Are we allowed to burn the flag?

Why, let me bend your ear

The media is dying

I can list the reasons why

Climate change is hard to solve

But stand back and I’ll try

How can we regulate fake news?

Well, listen to my plan

What’s to be done with Kayne West?

You’ve come to the right man

I have so many things to say

But here is what I’ll do

I’ll shut my stupid fucking mouth

You shut the fuck up too

Who Will Solve NASA's Poop Problem?

Seriously, you can win $30,000

Astronauts may be jacked math and science nerds with amazing hearts and lungs (plus chemically stable brains), but they all have at least one trait to keep them humble: they poop just like the rest of us. The reality of managing astronaut poop is actually a problem NASA is looking into now that we’ve hotboxed the Earth and are interested in longer-duration trips to places like Mars, because we’re going to require some new technology.

Let’s say you’re traveling to the international space station under the current poop model. You simply wear a diaper during the takeoff portion of the adventure, and then once you reach your destination, you’re free to hurl your poop out into the atmosphere like a shooting star for as long as you’re there. For longer commutes there is no protocol, though. And the diaper method is a lot less feasible.

That’s where NASA would love your help:

Basically the question is: how do we help people poop for days on end without compromising the barrier of their space suits, which they need in order to breathe?

They’re calling it the Space Poop Challenge, and they’re offering $30,000 to the person who can come up with a breakthrough.

What does a breakthrough look like? They lay it out on their site:

What’s needed is a system inside a space suit that collects human waste for up to 144 hours and routes it away from the body, without the use of hands. The system has to operate in the conditions of space — where solids, fluids, and gases float around in microgravity (what most of us think of as “zero gravity”) and don’t necessarily mix or act the way they would on earth. This system will help keep astronauts alive and healthy over 6 days, or 144 hrs.

Hm. Something that collects your poop for almost a week and stores it away from your body so you can still feel fun and flirty around your coworkers? Sounds like a fantasy.

Winning this contest is a bit of a double-edged sword, though, tbh. On the one hand I’ll respect you because wow you must really know your stuff, and on the other hand holy shit you are a true phreak on a leash for having this intimate an understanding of the poop crisis.

Anyway. It’s time to get cracking—the deadline for submissions is December 20. If you win feel free to Venmo me 10% of your earnings or name the dookie pump The Christine or something. A fair dowry.

There and Back Again

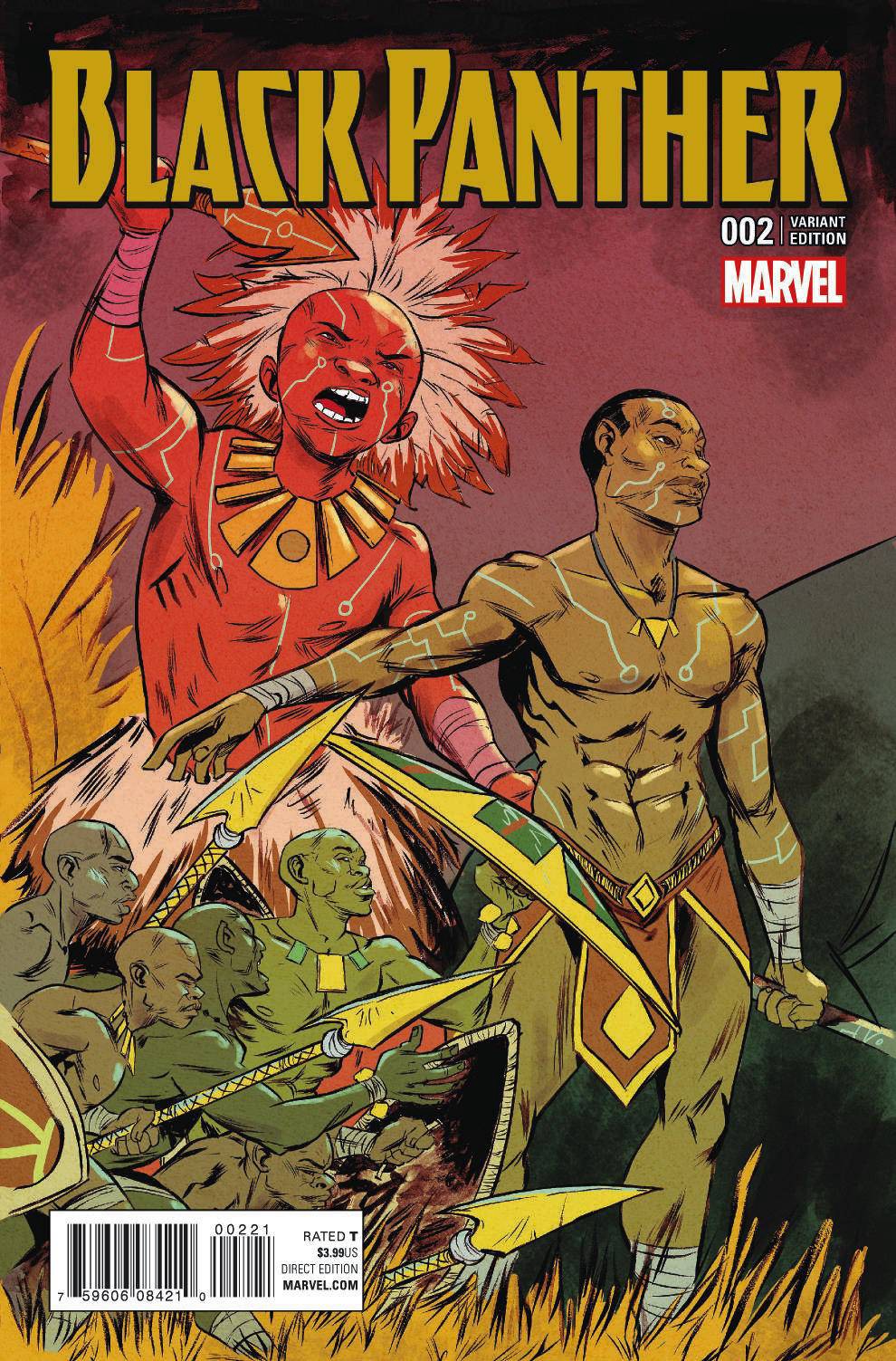

Why aren’t there more famous black sci-fi authors?

A few months back, the Fireside Fiction publishing company, released a comprehensive report detailing the lack of black authors being published in speculative fiction. Of the 2,039 stories that American science-fiction and fantasy magazines published in 2015, only 38 were written by black authors. More than half of the publications amenable to speculative fiction (a blanket term encompassing sci-fi, horror, and fantasy works) hadn’t published a black author that year, period. So the numbers pointed to calculated, institutionalized racism (hardly unfamiliar territory for the spec. fiction community), but, as usually happens, it was very important for a couple of days. People were capital-S shocked. Commitments were made. But then the static set in, and the literary world turned to complacency, and as generally happens, everyone forgot.

I grew up with speculative narratives lying all over the house. We were a middle-class black family living in a mostly white southern suburb. The wooden bookshelves sank under the weight of Frank Herbert and Stephen King and Brian K. Vaughan. Whole corners of whole rooms were stuffed with Timothy Zahn’s serializations. Susanna Clarke’s tome, Jonathan Strange and Mr. Norrell, occupied our coffee table. Whenever we had acquaintances over, they’d pick it up and flip it around and maybe bop their kids on the legs with it. And when company left, and the dishes were washed, and we were left to ourselves, my father would grab a tome by its spine, and my mother would settle across from him. I imagine the books were a respite from that monotony, and the codification of suburban blackness, and needing to be a certain kind of way: they were a reminder that, against all odds, the universe was ours to take. Whole corners of it had yet to be explored. We could be the ones to do it.

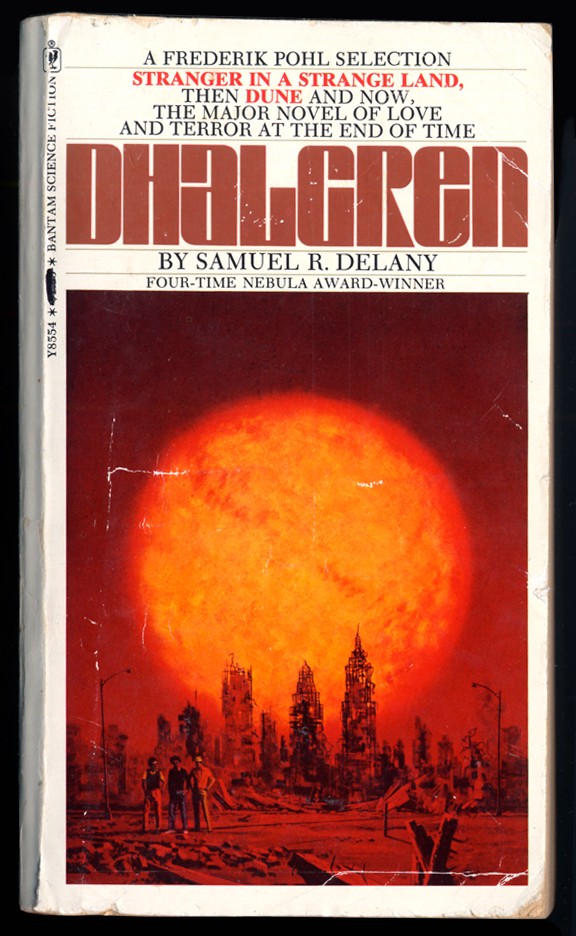

But none — not one — of those speculative authors on our shelves was black. I’d already moved out and left that little town and picked up books and put them down before I stumbled across a novel called Babel-17, in the dim basement of a dank downtown library. A black man wrote that book, his face spanned the entirety of the back of the dust jacket. I was completely flabbergasted. The thought of Samuel R. Delany’s even existing literally scrambled my brain. Delany had written loads of things, and much has been made of his being black while doing so, but I’d never heard of him, and he hadn’t existed to me until I found this interview months later.

Samuel R. Delany, The Art of Fiction No. 210

There’s a passage in the Paris Review piece that sticks with me:

Science fiction isn’t just thinking about the world out there. It’s also thinking about how that world might be — a particularly important exercise for those who are oppressed, because if they’re going to change the world they live in, they — and all of us — have to be able to think about a world that works differently.

I can’t explain how gratifying it felt to read that. I hadn’t seen any black speculative authors, so I didn’t think they were around. But here was this man telling me that not only were they out there, their experiences were a viable part of our universe’s functionality. Reading his words felt like being given permission to do something that hadn’t ever been an option before.

This isn’t to say that my experience with speculative culture had been completely bereft of dark bodies: I’d seen Lieutenant Commander La Forge, and I knew a little bit about Lando, and of course we’re all at least peripherally aware of Storm. I’d seen Blade parade across TNT, and Morpheus monologue in the theatres. I’d fawned over Zack. I’d walked out halfway through Cat-Woman. But it is one thing to see yourself on a leaping and shouting on a screen, and a whole different other to find yourself on the page in front of you. We were hardly in the books, and we certainly weren’t gracing their spines. The case remains largely the same in 2016.

American literary fiction, already an “other” within the business of fiction itself, consistently and predictably demonizes the minority entities within it. This isn’t exactly breaking news — we’ve arguably constructed an entire medium out of those very receipts — but what’s actively distressing is the aggression aimed at anything even skirting the notion of writers of color working within genre. If their narratives aren’t written in a supposedly “exotic vernacular,” reporting live from el barrio, or delivered with the express — but never too tempestuous — intention of conveying “digestible” outrage, minority authors often have a hard time getting a foot in the door; so to pen a piece set on another planet? In another galaxy? Navigating that market is, to put it lightly, a long-shot at best.

In some (most) supposedly literary circles, deeming the work of a supposedly literary author as genre is an assault in itself. There are occasional exceptions: an author already acknowledged as “literary” will be given a pass. Michael Chabon’s The Yiddishmen’s Police Union was one. Jonathan Lethem’s The Fortress of Solitude served as another. In 2014, Emily St. John Mandel’s Station Eleven carved a sub-genre were there was none before and Claire Vaye Watkins’ (lovely) Gold Fame Citrus fell into the same boat. But no black authors have been heralded for breaking that barrier yet.

It isn’t that they don’t exist: Nnedi Okarafor, Walter Mosley, Geoffery Thorne, Chris Abani, N.K. Jemisin, Victor Lavalle, and Carl Hancock Rux have been pushing out work for decades. But theirs books aren’t gracing the syllabi, and they aren’t being showcased with primetime reviews, and the press hardly rewards black authors equally in the best of cases, let alone through via speculative narratives. And it shows in the culture.

In an interview with Tor, Okarafor noted that fixing this discrepancy is a work in progress:

I think speculative fiction has fewer unspoken prerequisites than literary fiction for writers of color. I believe this is because 1.) Writers of color have a weaker foundation in speculative fiction. We are gradually creating a foundation. Thus, for now, there are few expectations. I think that will change. 2.) The nature of speculative fiction is to speculate, to imagine, to think outside the box. Speculative fiction is by definition better at doing this than literary fiction.

Daniel José Older, in a conversation with The Rumpus, pointed out that one of the chief causes is America’s reticence at large:

I think it really does connect to the fact that in 2015 we still need a movement to remind Americans that black lives matter. There is a question of relatable characters of color to a white industry, and it’s in the same conversation regarding white carelessness of black lives institutionally, and personally. When you read the tweets and see the video of the cop saying “Fuck your breath,” and all these other things that are happening, they’re all interrelated. They’re all not necessarily the same thing, but they’re interrelated, and it’s about looking at and asking about the empathy gap in whiteness that can’t conceive of the humanity of color. It’s about looking at what’s going on with whiteness there.

Both authors are right. The space for black authors in speculative fiction is continually being built, while the existence of those very spaces is still being challenged by their gatekeepers. And of course we plan to overcome those setbacks, to have a shot at constructing stories that capture the possibilities of everyday life. But these expectations are hardly asking too much as Octavia Butler conceded in a conversation with Charlie Rose: “Do I want to say something central about race except, Hey? We’re Here?”

There’s a moment in this novel, Charles Yu’s How to Live Safely in a Science Fictional Universe, that comes to mind:

Everyone has a time machine. Everyone is a time machine. It’s just that most people’s time machines are broken. The strangest and hardest kind of travel is the unaided kind. People get stuck, people get looped. But we are all time machines.

Because that’s the thing: everyone has the capacity for the fantastic within them. There’s no skin-screening to determine eligibility to make up stories, and it doesn’t matter which rung of our fictitious canon you’re writing from, but this is a statement accepted unanimously and emphatically circles until you emphasize that black people fall under it, too.

That’s when the question turns to qualifications and degrees. It’s when we start getting asked who gave us the right to be different. In his introduction to 1996’s Best American Short Stories, John Edgar Wideman puts that difference on its rightful pedestal:

Stories that don’t acknowledge the mystery at the center of things, don’t challenge the version of reality most consenting adults rely upon day by day, are stories that disappear swiftly into the ever-present buzz of entertainment. Stories that do mount a challenge to our everyday conventions and assumptions stir my blood. Not only because they are exciting formally and philosophically, but because they retain for fiction its special subversive, democratic role.

Reading Babel-17 opened other doors in my head. It was the work that made the existence of other realms even plausible. For some people it could’ve been the most recent Star Wars, and for others it might be this Ava DuVernay adaptation of A Wrinkle In Time that’s on the way, but the fact remains that these adventures still need to make it onto the page.

Because canons are constructed for the emergence of new narratives, and they don’t have to play out on a plantation in Georgia. Or a diamond field in Sierra Leone. Or a dark corner in some unnamed inner city, whose residents actively, notoriously, suffer from every conceivable calamity. And, despite whole industries working against us, we are seeing some progress: we’re watching princesses and presidents and hackers and mathematicians. Whole generations are being re-introduced to the world of Wakanda. We’ve even unearthed Creed. We’re making moves because we have to, because stories are what remind you that you’re really alive.

But there is also room for black voices in parallel universes. There’s room for black voices in the future. The space will be there for as long as we have the people here to fill it. But despite the opposition we’re facing in carving it, or perhaps even because of it, we’re already living in that future.