Arandel, "Aleae III"

Nobody knows anything, but especially the people who tell you it will all be okay.

It’s cold and gray and wet outside and we’re still closer to the beginning of the week than the end of it. That’s the good news. The bad news is every other thing and how much of it there is. It’s a list that is only growing.

Here are eight minutes of electro that, if nothing else, are eight minutes that are not anything else. “Not anything else” is as good as it gets for us from now on, so consider that before you get all sniffy about electro. Enjoy!

New York City, December 5, 2016

★★★ Clinging blue tendrils of the rainy night held back the arriving day. An older brother in a checked huntsman’s cap and a younger brother in a soft hat with antlers chipped away at each other waiting at the elevators. The five-year-old steered around every puddle but the last one on the way to kindergarten. The light gray clouds and the lighter gray ones were hard to tell apart but were moving fast against one another. By late morning, bright spots had inserted themselves into the blurry motion, and then a clear afternoon came on. Young people sat on the travertine steps, wrapped in the travertine-tinted light, regardless of the chill. Loudspeakers sent “First We Take Manhattan” thrumming over the stone of the bare plaza.

"Gifting" Is Gross

An arbitrary vocabulary preference, explored

One thing people like to talk about that traditionally moves my barometer 0.00 fucks is the word “moist.” Are you familiar with this phenomenon? A not-insignificant percentage of the population really hates it. The sound of moist, the look of moist, idk. It bothers more people than you’d think, and they love to identify themselves and tell you about it*. “Panties” is another popular word to hate. Neither of them do it for me, but if I think about the condition hard enough I can sympathize. The same way that if you say “Kevin” over and over again you eventually start to realize how random and dumb language is. Kevin does not exist. We made Kevin. Kevin.

But this time of year, a certain kind of word sees a spike in popularity and it curdles me to my core—that word is “gift.” Specifically, gift used as a verb.

“The vase you gifted Susan is so fun!”

Something about that word used that way gives me hives. It makes me want to cover all of my sensory organs and strap on a thunder vest. Gift.

Gift, to my mind, exists as a synonym for “special object,” end of list. Your common law husband gave you a gift for your last birthday. You sang at your bat mitzvah, and it’s clear to all of your aunts that you have a gift. As a noun, the word is inert. Even the adjective—gifted—is fine. “Shelly is in the gifted tuba program at school and we are very proud.” Good for her! But to interchange “gift” with “give” or “gave”? Hoo! Daddy Yankee! It makes some circuit board in my brain catch fire and sets off an alarm and the sprinklers start spraying.

“Bad!” my brain shouts. “Ugly!”

I don’t know what the problem is. The dictionary says we’re allowed to use the word that way, but I am staunchly opposed nonetheless. Is this what happens to “moist” people? Or “panties” people? Does it feel as though all of the blood in your veins has suddenly become battery acid and you need to jump out of your skin in order to avoid hearing the sound of that word exiting someone’s mouth even one more time? If so, I feel you.

I asked my coworkers what they thought, and they seemed to generally share my sentiments (though admittedly not as strongly).

Are we in the minority? I have no way of knowing. “Gift”-haters seem to be a little more covert than “moist”- and “panties”-haters, so maybe we’re a silent majority. I’ve decided to try to find out.

For the next 24 hours, I will be running a poll re: your stance on the word gift. Please weigh in:

do you feel comfortable using gift as a verb? (ie: “i gifted that sweater to you!!!”)

I will report back to you with my findings and analysis.

______

*Kind of like how people also love to take a stand re: Oxford commas in their Twitter bio. How and why? Small-scale trends on micro issues.

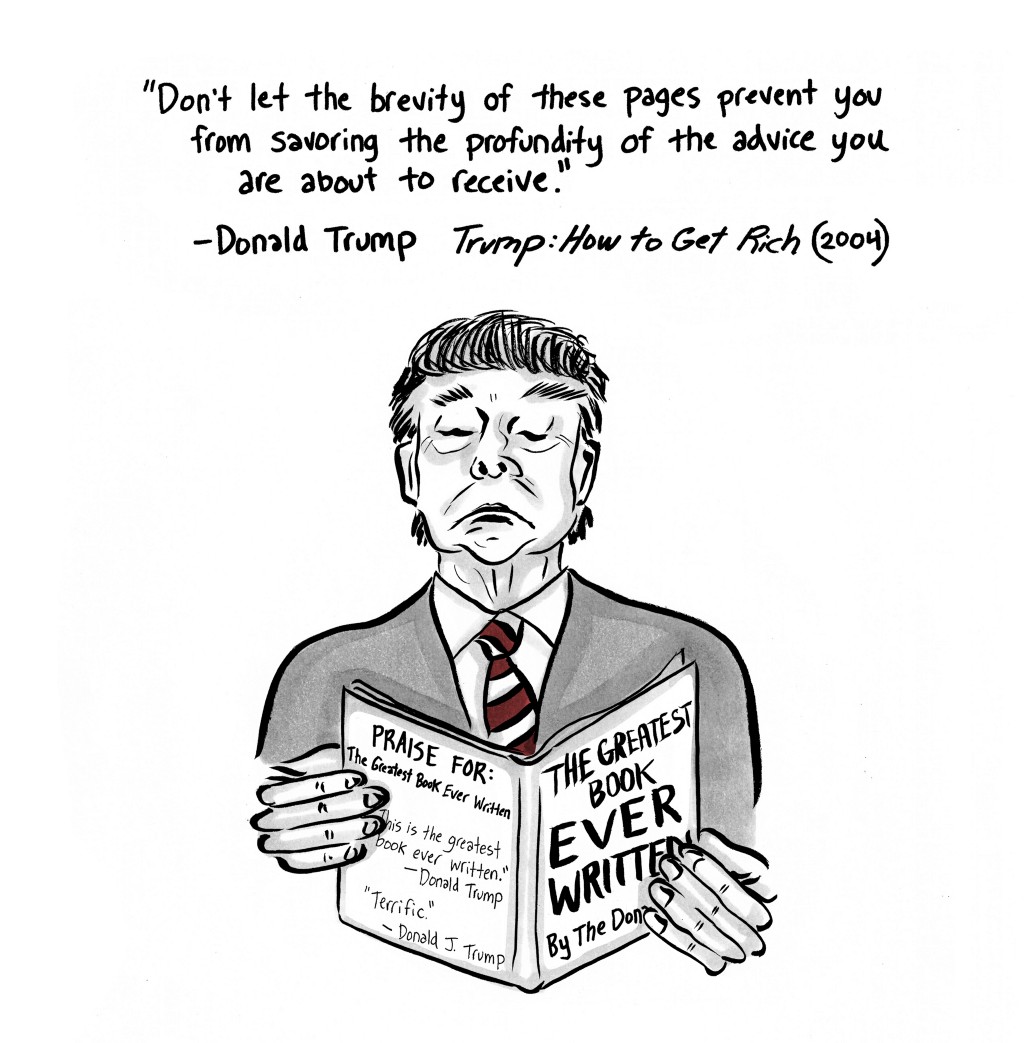

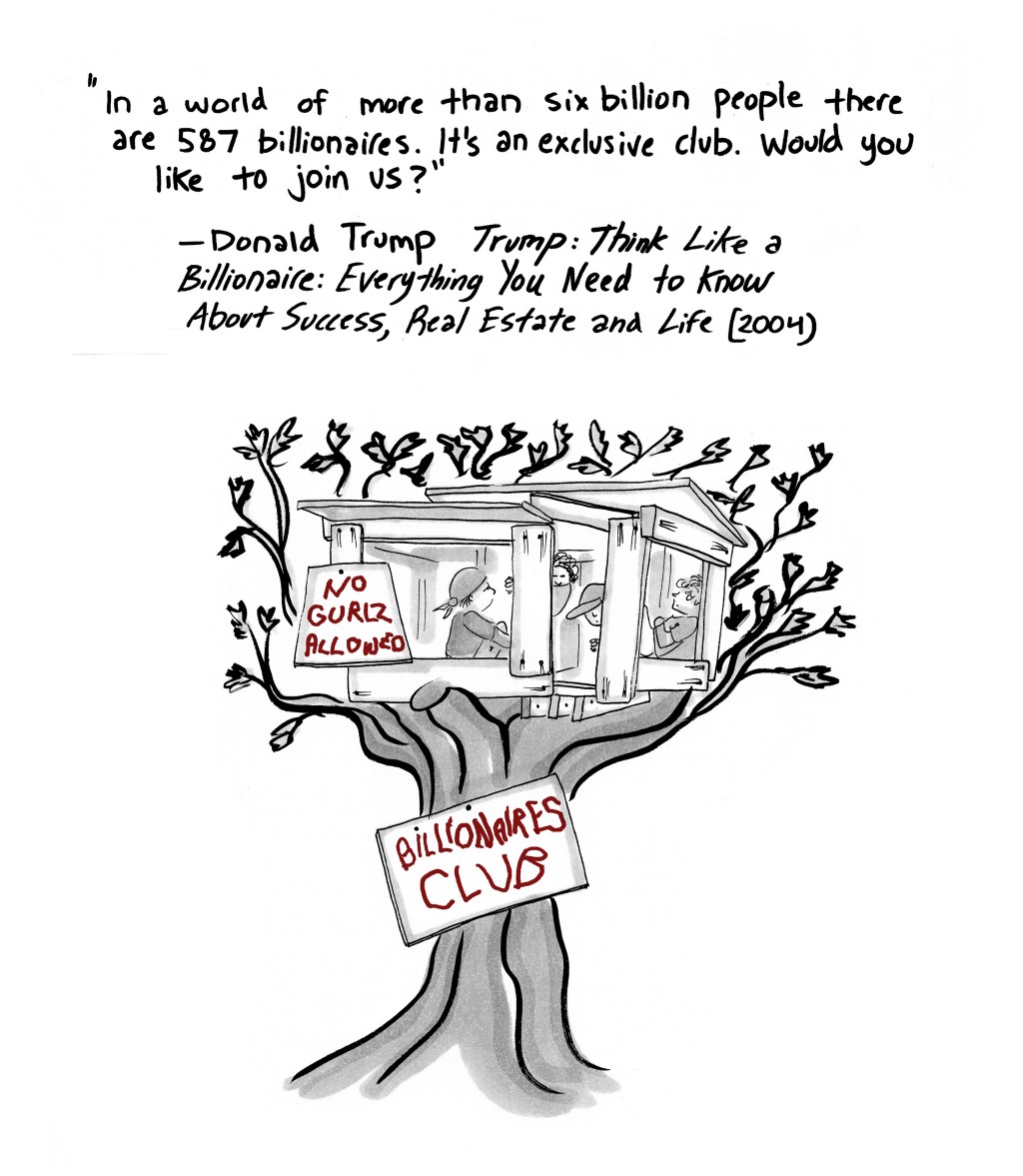

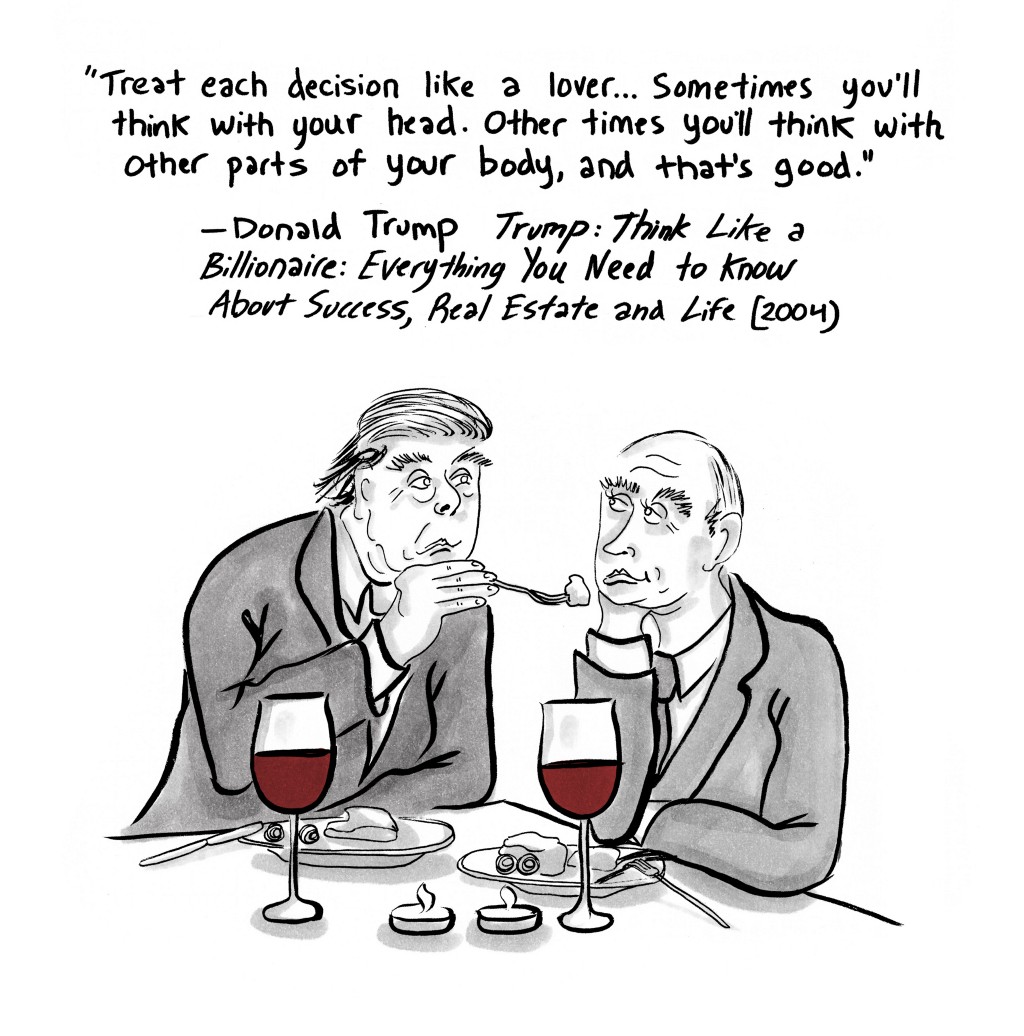

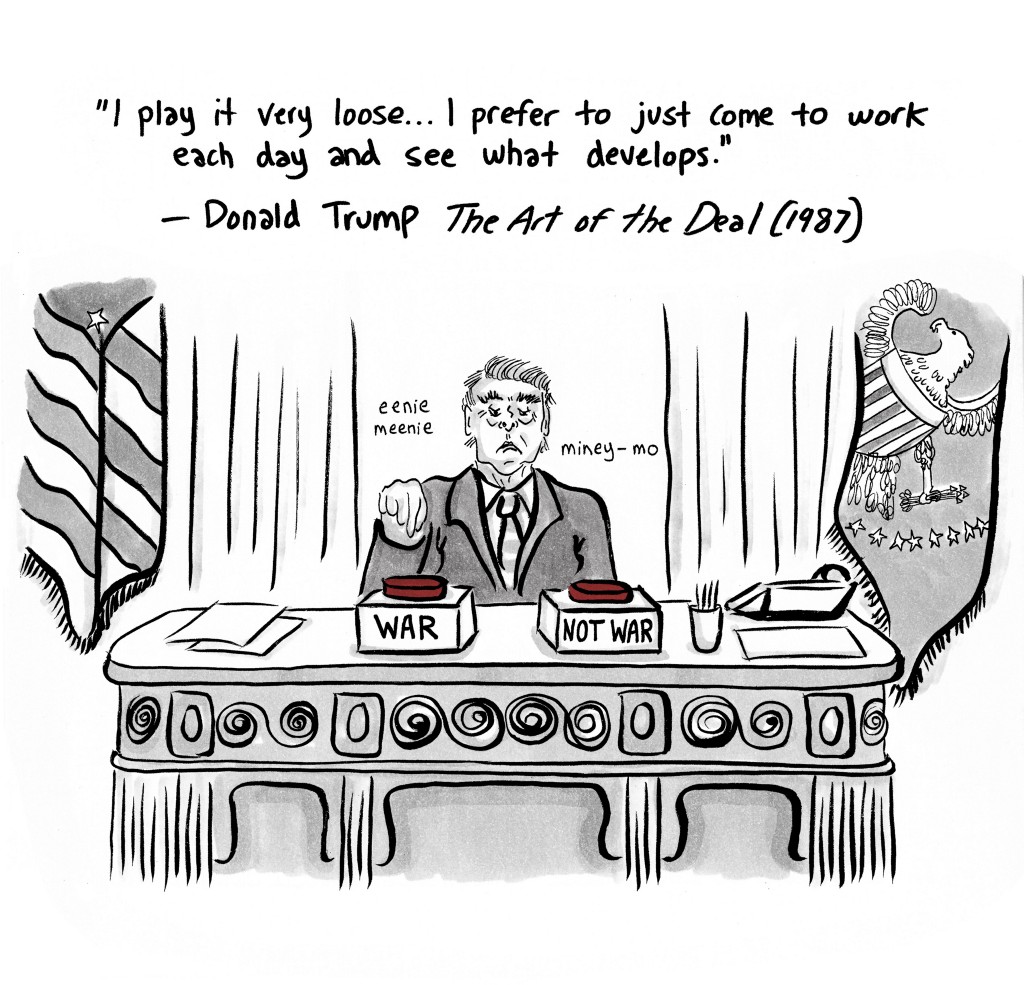

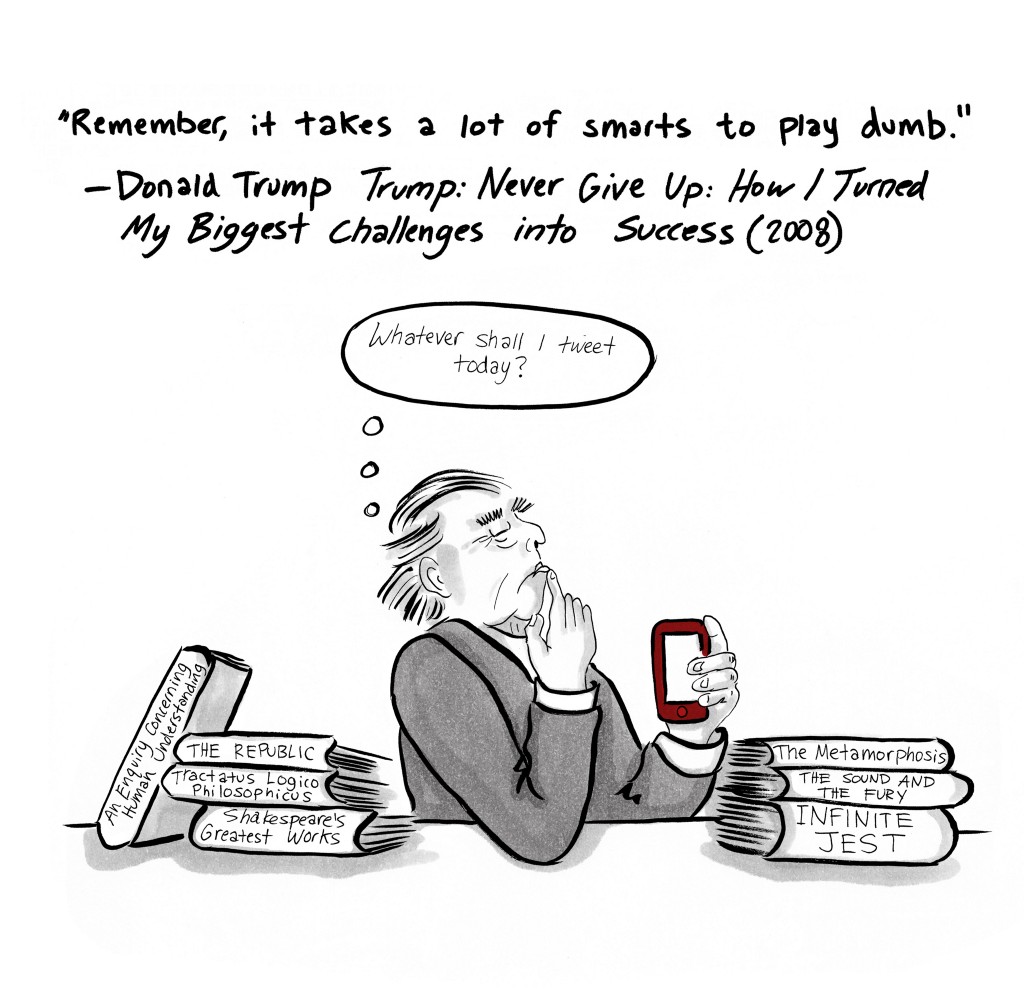

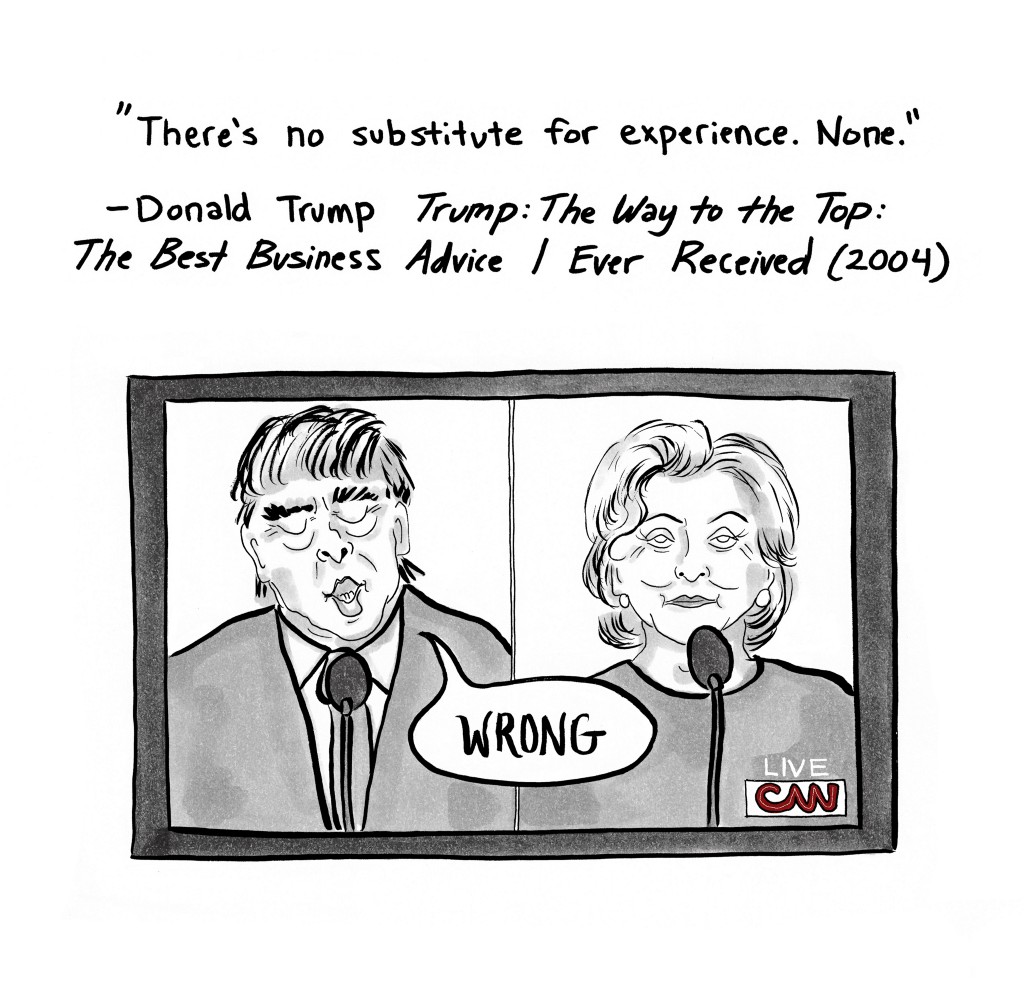

The Illustrated Donald Trump

Selected quotations from the President-elect’s books, visualized.

Amy Kurzweil is the author of Flying Couch: A Graphic Memoir. Her cartoons have appeared in The New Yorker and other publications. For more comics follow her @amykurzweil.

The Arc Of The Atlatl

The rise of spear-throwing among hobbyists and modern hunters

In the autumn of 2007, Aaron Swope of East Hempfield, Pennsylvania, killed his first deer at the age of seven. His grandfather, 61-year-old Russell Guthrie, who’d brought the boy out to hunt near Buck, Pennsylvania, that day, caught the kill on video and posted it to a local outdoorsman forum. Almost immediately, the video was drowned in a hail of gushing-to-critical comments from the state’s hunting community. Some were impressed that a boy that young had not just made a kill, but had done it after sneaking up on the deer and striking it from just 15 feet away. Some were judgmental about the fact that the kill happened on a private preserve, where the deer tend to be more docile, less skittish — not a fair hunt. But the vast majority were captivated by what the boy had used to bring down the deer: a six-foot-long dart launched from a shorter strip of wood he held in one hand, a prehistoric hunting tool (not so) commonly known as an atlatl.

Not long ago, few people could identify an atlatl, much less known how to pronounce it. (It’s aht-lah-tuhl, not atl-atl.) Actually even today few in the general populace can. Yet in recent years, a small but growing group of enthusiasts have worked to revive interest in and knowledge of this simple, ancient weapon. In America, it’s caught on especially with certain subgroups of hunters, who proselytize the joys and value of working with atlatls. Some of acolytes of the elegant yet rudimentary device see it as a novel challenge — a fun new test of their physical skills. But for many, especially in the hunting community, the atlatl is a symbol of romantic primitivism through which they can write themselves into thrilling, virile narratives of the hazy, heroic past.

For the uninitiated: atlatls are basically pre-historic ball launchers; their underlying mechanics are similar to those involved in the Basque sport of pelota, or jai alai as it’s known to many in the Americas. A length of wood, bone, or ivory is carved into a board, about two feet long, with a handle at the front and spur at the back, upon which a long dart with a pointed tip sits. A thrower draws the atlatl back in one hand, holding the dart in place with a hooked finger, then hurls the apparatus forward, loosing the dart. There’s some variation depending on the design and the darts used, but many launch their projectiles at up to 100 miles per hour, with accuracy of up to 40 yards, achieving about 200 percent more penetrating power than a dart thrown by hand.

“It takes very little to make either the atlatl or the [dart], and both are immediately usable,” said Elizabeth Horton, a University of Arkansas archaeologist. She’s hosted events for people to try their hand at flinging atlatls, among other prehistoric human skills. “It’s an extremely difficult skill, but one that you can do with a wide range of people and age groups.”

This simplicity and power likely accounts for the wide usage of atlatls throughout many of the world’s ancient societies. Although some believe humans have been using atlatls for 30,000 years, the first evidence of them shows up in European cave paintings from 15,000 B.C.E. Evidence of them has been found everywhere in the world, save (to date) in sub-Saharan Africa. In America, they’re best known through accounts of the Spanish confrontation with the Aztecs, from whom we get the term “atlatl” and who, used the devices, which probably traveled with humans as they first moved to the continent, well into the 16th century C.E. But other groups, from Australia (where some aboriginal peoples called them “woomera”) to the Yukon (where the Yup’ik peoples called them “nuqaq”), likewise used atlatls to hunt and fight into the modern era.

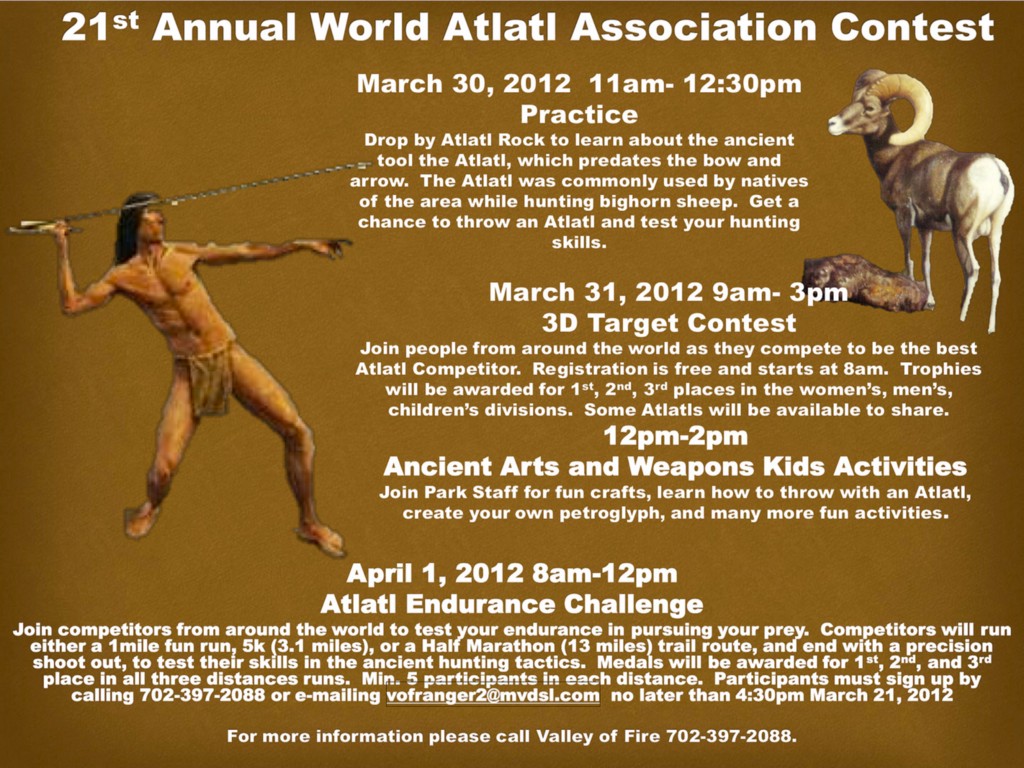

Experimental archaeologists have long played around with reconstructed atlatls, to understand their research subjects and to unwind alike, but at some point their enthusiasm spread to a critical mass of students. In 1987, a group of wonks formed the World Atlatl Association (W.A.A.), which brought enthusiasts together for accuracy competitions, like the International Standard Accuracy Contest. There was enough interest by then that some folks, like William “Atlatl Bob” Perkins, who’d built his first device for a term paper while at Montana State University in the 1970s, were able to launch companies — Perkins’s BPS Engineering out of Manhattan, Montana, is one of the bigger and better known outlets — selling dart throwers of all sort for collection and sport.

“I [throw atlatl darts] to have fun and see my atlatl friends when I make it to events,” said Courtney Birkett, executive director of the WAA and a working archaeologist, of the draw of the devices for her and many academic types. “I’ve sometimes thought it’s like anything else that has a devoted following — like science fiction or other things that have conventions.”

In those early days, only a handful of people were interested in reviving the actual use of atlatls for hunting. Bob Berg of Thunderbird Atlatl in Candor, New York, near the Finger Lakes — another big name in the atlatl world and an advocate of atlatl hunting — said when he got into the community in the late 1980s, there were perhaps half a dozen atlatl hunters in the nation.

Once Berg and his cohort started spreading the gospel of the atlatl in the hunting community, though, it took off in a major way. There are nowhere near as many atlatl hunters as there are bow hunters even (in no small part because it’s hard to find places in which it’s legal to hunt with an atlatl). But while about a quarter century ago you could perhaps count the number of atlatl hunters on your hands, today Berg suspects that of the thousands of atlatls he sells each year, about ten percent go to hunters. The community of atlatl hunters has grown so quickly and enthusiastically that they’ve even formed the Atlatl Hunting and Fishing Association, backed by Berg, to lobby for the legalization of atlatls as hunting tools in regulated zones across America.

Atlatl hunters aren’t a huge lobby, but there’s enough vim and vigor in it that they’ve succeeded in pushing atlatl-hunting legislation in Alabama, Missouri, and Nebraska in recent years, meaning that you can hunt for regulated game with a prehistoric dart thrower in four states now. At least one bill to legalize atlatl hunting has floated around in Montana. (Atlatl hunting was apparently always legal in Alaska, and many others have long allowed the use of any weapon to hunt unregulated animals, or allowed the use of atlatls to spearfish.) They managed to get it provisionally cleared in Pennsylvania a decade ago, but within months the implementation of a hunting season was shelved indefinitely due to concerns about the lethality of the device, especially in the hands of amateurs, and their potential to cause undue animal suffering. (Private preserves, like the one Swope killed his deer in, are free from these restrictions in Pennsylvania and some other states.)

For some hunters, like 50-year-old Paul Gragg, who made Missouri state news last fall when he took down a massive whitetail deer with a seven-foot dart with a twin-bladed broadhead tip in the wild, five years after the state legalized atlatl hunting, the devices are just a new challenge — something to get excited about after years of bow-hunting, for which he holds local records.

“A guy told me no one had ever killed a deer in Missouri with an atlatl, so I though it might be interesting to try,” Gragg told local reporters. (This wasn’t actually true. The first deer was brought down with a modern atlatl in Missouri in 2011.) “I’m not real educated on the history of atlatls — it’s just another opportunity the conservation department offers for hunting.”

But for many others, the atlatl’s appeal is all about connecting them to what they sometimes describe as the “roots of humanity.” Some atlatlists have argued atlatls were the technology that transformed us from scavengers into hunters — and implicitly turned us from passive animals into potent men, stewards of the earth. Others talk about it as a means of traveling back into the past, away from a technologically dominated now.

Many events featuring atlatl trials advertise the dart flingers as a measured, hands-on means of gaining an intimate and physical understanding of and respect for archaic life. Firing an atlatl “is one of the quickest ways to get out students to think about past life in a more personal way,” said Horton. “It immediately dispels any lingering notions of past peoples being ‘primitive.’ Anyone can ‘do it,’ but it takes a lot of skill and knowledge to do it right and well.”

Hunters like Berg attempt to be methodical and academic in their approach to exploring the past through atlatls. He recalled that he recently brought a young man on an atlatl hunt with stone tools with which to butcher a freshly slaughtered deer as part of research for a Masters thesis. For Berg, these pursuits about holding fast to traditional knowledge, or dredging it up from the depths of time as best as possible, to keep a piece of the human narrative from slipping away.

However, some veer into talking about atlatls as a means of better understanding local indigenous cultures in a way that feels worryingly like an unintentional exercise in “playing Indians” in the guise of deep anthropology. A local story on a new atlatl event put on by Arizona City’s Pueblo Grande Museum in the spring of 2014 featured descriptions of organizers hitting cardboard sabre-tooth tigers with atlatl darts and claims about the inherent, marrow-deep human affinity for atlatl-throwing alongside notes on appreciation for local indigenous culture. Another event, this summer’s “18th Annual Bald Eagle Knap-In, Native American Primitive Arts Show & Atlatl Tournament” at Pennsylvania’s Bald Eagle State Park, advertised itself with the following phrase, laid out immediately beneath a banner of clip art stone arrowheads flanking crossed clip art spears: “This exciting two day festival will transport you back to a time of primitive life.”

Atlatls and atlatl hunting show up on survivalist forums and primitivist portals, which promote disengagement from modernity in favor of a simpler, cleaner, and more meaningful past of raw human skill and ingenuity. It’s an old impulse — the same one that’s long led scout troop masters to teach their wards how to do things the old way. It’s am embrace born of despair with the modern world and a deep belief that prehistoric technologies are either essential for a coming apocalypse, or that they are morally superior in their simple elegance.

On the edges of this impulse, or at its core, is an Edenic, Rousseauian view of primitive man and the primitive world. It’s an image of early hunters not as complex peoples in perpetual and dynamic technological and social development, but as stoic and skilled moral agents, possessing an autonomy and power we wish to possess for ourselves again. It’s an image of the past that strokes and stokes what it means to be masculine, to be a provider, to be a capable individual.

Atlatls are amazing. They are incredibly efficient for simple bits of organic matter, drastically increasing man’s natural might through a little skill and knowledge. Their proliferation across human cultures speaks to a common ingenuity and development, one of those rare universal human narratives. They can serve as portals into a rich and diverse past. But especially as they bump up against and spread into communities with their own philosophical readings of the past, they can also transport us into myth. We ought to be keenly aware of where these ancient devices take us, and what baggage we bring into our encounters with them as well.

Mark Hay is a freelance writer living in Brooklyn.

10 Other Possibilities For Person Of The Year

Here are some alternate choices!

10. Who Cares?

9. It Doesn’t Matter

8. None Of This Matters

7. Even Jokes About This Are Irrelevant Now

6. The Whole Fucking Thing Is Irrelevant

5. You Could Be Doing Anything Else At This Moment, Including Staring At The Fingerprints On Your Phone Or Picking Your Teeth With A Magazine Subscription Card, And It Would Be Of More Value To You And The Universe Than Whatever Discussion About This Non-Event You’re Having

4. It’s A Waste Of Everyone’s Time

3. Why Are We Even Talking About This? What Are We Trying To Distract Ourselves From?

2. Oh, Right, That

1. Ugh. All There Is Left Is Ugh.

How To Not Drink At The Office Christmas Party

Sometimes your inhibitions are actually useful.

“Why is drinking at office parties such a thing in the first place?” I asked my husband.

“Movies and TV,” he said. “Movies and TV have made people think office parties are romantic. Like Love, Actually.”

“That party’s not romantic, though,” I said. “The thing with Alan Rickman and his secretary ruins his marriage.”

“Yeah, but what about Laura Linney and the guy she likes. Don’t they get together?”

“No, because she fucks it up,” I said. “She finally has Rodrigo shirtless in her bed and she keeps getting up to answer the phone. I can’t even stand to think about it.”

“Is his name really Rodrigo?” my husband asked skeptically.

“Like I would forget the name attached to that torso.”

“Fair enough,” he said.

So maybe Love, Actually proves two points: that people do think office parties are opportunities for their real, non-officey feelings to shine, and that they’re really breeding grounds for awkwardness and regret. Sure, maybe you won’t wake up in the wrong bed at 4 a.m. with cigarette tongue, or throw up in the stall next to your boss. But you could easily say things the sober you would never say or even want to say, to your crush or your boss or your cube-mate, which could be more lastingly awkward and painful than one teeny blip of a sex or vomit mistake.

For that reason alone, it might be wisest to kill your Jim-and-Pam fantasies and treat the office party more like Work: Merriment Edition. Gamify it: go in with a list of people you want to talk to and make it happen. Or pay attention to who isn’t drinking. In my first year of sober work parties, it dawned on me that the world is crammed not only with recovering alcoholics, but with gazillions of other people who just don’t drink — because they’re Muslim or Mormon, because alcohol triggers their migraines, because they don’t want the calories. If the overall vibe is getting too boozy, home in on another non-drinker and chat about something. It doesn’t really matter what. You’re just looking for a place to anchor yourself and a reminder that totally normal people do these things sober all the time.

Gee, thanks for the handy tip about befriending Mormons, you’re saying. But I’ll never get up the nerve to ask Jake from Legal to go to SoulCycle with me without a drink! Or to sell my division VP on how the Internet of Smells is the next big thing.

Sure you will. Maybe not at this particular party. But you will. Unless, of course, you keep relying on booze to cope with garden-variety human jitters. Then you won’t, because you’ll never get the practice. You’ll keep sending out an altered version of yourself to face the stuff that makes you nervous, and then doing version control the next day. Maybe it’s subtle version control — most of us don’t go around shrieking “Sugar tits!” at people like Mel Gibson when we’re drunk. But you’ll still be managing multiple selves.

And I can tell you this: your drunk self is not funnier, sexier, smarter, or more interesting than your sober one. It’s just less inhibited. And inhibitions, while not the most glamorously bohemian things in the world, are something better: they’re useful. Especially at work, where — catchphrases about “bringing your whole self” aside — you are employed because of specific skills, knowledge, and behaviors that your employer needs to reach its goals. Yes, you’re a person. But you’re a person in a role. Your inhibitions remind you not to lie about a deadline just to get someone off your back, or to speak harshly to the intern who’s just doing her college-senior best, or to pick up a conference table and fling it through the window while primal-screaming in an ancient language of revenge.

Your drunk self is not funnier, sexier, smarter, or more interesting than your sober one.

Here’s the best thing about inhibitions: they’re a good filter for the impulses and questionable ideas that actually are worth paying attention to. Let’s say you’re at the party, a mere three or four drinks in, and thinking that instead of inviting Jake from Legal to SoulCycle, maybe you should cut to the chase and just accidentally get trapped in the stairwell with him. Drunk You won’t know if you really want that, or if it’s just the dopamine talking. But if Sober You thinks it sounds like a plan? I’m not an H.R. professional or a career coach (for which we should all be grateful). All I know is that the harebrained schemes, longings, and impulses that make it through my own filters of inhibition and sobriety often turn out to be, at minimum, genuinely interesting. And I’m able to give them the consideration they deserve, and usually (okay, fine, often) make the right call.

So who knows, maybe you’ll get your movie ending. Maybe two years from now, you and Jake will get married in the very same stairwell where you first kissed at the office Christmas party. Just give me this: start in the way that you want to go on. Start as yourself.

Aquaserge, "Tour du monde"

It’s another day in a endless parade of another days.

Just listen to this and try to enjoy it. Nothing else today is going to be as good, and I don’t even know whether you will think this is good or not yet. All I’m saying is whatever happens after is going to be bad, even if you have gotten to the point already where you’re so used to things being bad that any day where you don’t catch fire seems not terrible to you. Even if you have amazing plans tonight they are not going to be as good as spending four minutes just listening to something and not thinking about anything else, because I have already told you about anything else. Still, I will reiterate it for your benefit: it’s bad. So shut everything else out for four minutes and enjoy as best you can. After that you’re on your own.

New York City, December 4, 2016

★★★ The clear sky gradually whitened, with faint streaks on it. The five-year-old tore around the apartment till he agreed to go down front for a while with his basketball. The one knit glove he could find, he eventually started wearing on his lead hand as he dribbled. Down on 42nd Street, the wind couldn’t do much to slice through the crowds. A grimy Elmo hunched by the outside of McDonald’s, counting money while propping a Minnie Mouse head against the wall. Fake snow sifted down inside the doorway of the wax museum. Under the lights, it was possible to deceive oneself that night had not already fallen.

Belcher Family Values

“Bob’s Burgers” is an exception in the world of animated sitcoms: The Belchers actually like each other.

The pantheon of animated family sitcoms isn’t really a happy place. In “South Park,” the kids’ parents are essentially absent, and they live a depraved and vulgar life on the prairie. In “The Simpsons,” Homer is a drunken buffoon, Marge is an enabler, Bart is a borderline juvenile delinquent, Maggie is often forgotten, and Lisa struggles to be a moral person in an often amoral family. In “Family Guy,” Peter and Lois are extreme narcissists and, in Peter’s case, occasionally abusive. Stewie is a Bond villain, Chris is potentially developmentally challenged and receives zero support, and Meg’s character mostly exists to be the butt of jokes. The only real adult in the family is the dog, and he’s a drunk.

“Bob’s Burgers,” which airs on Fox is an exception to the rule of dysfunction. Bob Belcher runs a boardwalk burger joint, which usually loses money. His wife Linda involves herself in other’s people business and devotes herself to raising their three kids, Tina (thirteen, awkward but preternaturally confident) Gene (eleven, goofy, and devoted to becoming a musician), and Louise (nine, a spunky troublemaker in pink rabbit ears). Bob and Linda try to raise good kids, and the kids seek to live up to their expectations. It would be precious except that the kids are super weird — Tina, for instance, writes erotic “friend fiction” about zombies and her school friends getting down — and the restaurant always seems to be on the brink of bankruptcy: The Belchers depend on the patronage of Teddy, a guinea-pig loving handyman and Mort, who owns the mortuary next door, to keep the business afloat.

The Belchers’ philosophy about their children is on display in season four, in an episode titled “Gene It On.” The episode opens with Bob wondering who took his mop head. Then Tina walks in carrying it and Gene’s “Rasta Wig” like pom-poms — she’s trying out for the cheerleading squad. Tina is a permanently deadpan hall monitor. If confronted with a socially uncomfortable moment, she groans while making deer-in-the-headlights eyes. But she wants to cheer so she can stand in the “splash zone” from the boy’s wrestling mats. No one in the family knows she’s trying out, since she’s been practicing in the closet.

Bob is understandably worried. “Tina, do you really think you’re the cheerleader type?”

“Bob, be quiet,” says Linda. “Come on, what cheer you gonna do for the tryout?”

Tina limply recites a cheer, “Let’s go. Ignite. The Wagstaff team is dynamite.”

“Okay, we’re ready,” says Linda.

“I just did it,” Tina replies.

Linda does what any good mother would do: she makes Gene and Louise go to the tryout as well to cheer Tina on. If this were an episode of “Family Guy,” the Griffins would all go to the gymnasium to laugh at Meg. While the initial conceit of the episode is hilarious — that Tina, who is the last person in the world who should be a cheerleader, wants to be a cheerleader so she can be splashed by the sweat of pubescent boys — the core of the plot develops around Gene and his (literally) belly-slapping enthusiasm for his sister. Rather than rely on non-sequitur or coincidence as “Family Guy” or “The Simpsons” would to drive the plot in the same scenario, the episode revolves around a sibling dynamic initiated by Linda’s active parenting.

In season three, episode 7, “Tina-rannosaurus Wrecks,” Bob’s having one of the best days of his life. He’s just bought 6,000 two-ply napkins for $58 — a deal. Tina is with him in the empty parking lot, and Bob gets an idea; he invites Tina to drive the car for the first time.

“Is that legal?” Tina asks.

“Well, no, but my father let me drive when I was about your age. Call it a perk for running errands with your dad,” Bob explains. (Neither the Griffin nor Simpson children have ever willing assisted their parental units in running errands — this is uncharted territory for animated sitcoms, and it allows the humor to derive from Tina’s generalized awkwardness and Bob’s awkwardness in being her father.)

So Tina begins to drive, emitting the glottal groaning noises she makes under duress, and, despite moving at a crawl, somehow manages to crash into the back of the only other car in the lot.

“Oh my god it’s bad,” Bob says, holding his head.

“I ruined the car.” Tina deadpans.

“You did, you really did. Well, okay, uh. At least there doesn’t seem to be any damage to the other car.” Tina freaks out, gesticulating and pointing wildly.

“No, I see a dent. There’s a dent!”

“No, that’s a ding. No even. It’s like a little scratch.”

“No, it’s a dent.”

“Alright, we’ll leave a note!” Bob says. “You know, then again, for all we know, that probably was there.”

“We have to leave a note! We have to leave a note!” Tina yells.

“Okay, okay. You’re so honest… who raised you?” Bob says, beaten.

“I don’t know!” Tina is still upset.

“It was me. I did.”

Bob is dealing with a classic adult problem — he doesn’t want his insurance rates to go up — while also trying to be a good example for his daughter. It’s this tension, between adult desire and what Bob and Linda firmly believe to be their moral duty to be a good example, that precipitates most of “Bob’s Burgers” plots.

In episode 10 of season five, “Late Afternoon in the Garden of Bob and Louise,” the tension between adult desire and the needs of children reaches its peak. Bob wants a plot in the community garden — he mistakenly believes he will find it soothing and spiritually fulfilling — but he has to convince the woman who runs the garden, Cynthia, to give him a plot. So Bob cuts a deal: he gets a garden bed but must take on Cynthia’s son, Logan as an “intern” to provide fodder for his summer camp essay.

Once pea, green bean and tomato sprouts start coming up, Bob breaks into song, “I think I found my happy place.” The plants even start dancing. After Louise and Linda get into a fight with Logan and Cynthia, Bob makes Logan employee of the month so that Cynthia doesn’t take back his garden plot. Eventually, Louise steals Bob’s gardening shears with the intention of destroying Bob’s plants.

Bob, chasing her, blurts out, “Louise, please. Those are my babies!”

She looks at him with big, offended eyes. “What? These are your babies?”

“Yes, those are… oh. Why did I say that in front my actual baby…. Maybe this whole garden thing was maybe a little bit selfish,” Bob says. And he gives her permission to cut down the plants.

A moment later, Bob apologizes for hiring Logan. “I’m sorry I hired Logan. I know how much you don’t like him.”

“Yeah, I’m pretty open about that dad. Plus, I mean, the restaurant is our place and I like it that way.” Bob even asks for Louise’s forgiveness. And she gives it to him (after a bit of negotiating — she wants to fire Logan herself).

Bob has to play a very active role in Louise and Tina’s lives. Gene, the middle child, often gets overlooked. He’s less neurotic than Tina and less of a troublemaker than Louise. He dresses up as 1990s Queen Latifah for Halloween. There are perennial questions about whether or not he’s gay. The show never tells us, but the strength of the family is apparent in how Bob, Linda and his sisters always accept him for who he is. Linda praises his costume and the whole family goes to the underground school music version of Die Hard that he puts on.

This is the essence of “Bob’s Burgers.” No one is exceptional. The Belchers love each other despite their foibles. “They all have a vulnerability to them, and they all are passionate in different ways,” said Kristen Schall, who voices Louise. And Loren Bouchard, the shows creator, contrasts the show with “South Park.” “I respect the rights of any show, and particularly animated shows, to [be mean] if they want to… if they are particularly good at it. I’m thinking of ‘South Park’…. It’s just not something we were interested in doing.”

What “Bob’s Burgers” is good at is creating a family of real people who aren’t perfect but who care for each other. The parents actually parent their kids (or are they the titular burgers?) and the kids actually love each other. They try to be decent people. And as viewers, we appreciate that. They might struggle to sell burgers, but the Belchers have each other. And the image of a long-suffering line-cook and his enthusiastic wife trying to turn their kids — including a son who bathes in a vat of beans just to find out how it feels — into well-adjusted adults, is always hilarious.

Benjamin Reeves is a New York-based journalist and editor whose work has appeared in Worth magazine, USA Today, The New York Times, Vice and the Miami Herald. Follow him on twitter at @bpreeves.