Just Ten Bucks! We Want To See You Tonight at Carnegie Hall

by Seth Colter Walls

American culture is rotten to its core. Not only is Natalie Portman pregnant-while-not-married, but there is such a thing as “public television” and also a thing called the National Endowment for the Arts. If only we could convince the last remaining holdouts that mass culture is the only proper artistic reflection of a democracy, they could all join in on making endless japery from the outputs of a serial woman-abuser who is equally popular on both network television and Twitter! Then it might be, if not quite morning in America, something other than twelve strokes to the dead of midnight.

Yet that is where currently find ourselves. Perhaps with a few more protests targeted at certain less-familiar-looking members of our citizenry we could vault magically forward in time, to that better tomorrow. But a simple perusal of the lineup at Carnegie Hall’s basement space this evening proves how far we’ve fallen. (Also: why is Carnegie Hall allowed to have a “basement” space? The closer to hell, the better, I suppose.) Even worse: now they are seducing people like you with $10 tickets for tonight’s program, which are available right now, right here.

What terrible wonders will you see? We shall tell you!

Joan La Barbara is a vocalist and composer who has worked with three of the artists featured on PBS’s “American Masters” program (nos. 152, 127 and 43 on this list). Which is bad enough! However, Ms. La Barbara also composed and voiced one of the early, iconic “Singing Alphabet” numbers for Sesame Street, before that television program was made semi-acceptable via an increased reliance on appearances by celebrities.

A radical organization called the American Composers Orchestra, after a nationwide search, has asked her to compose a piece that they are going to premiere down in Zankel Hall tonight. A piece for an orchestra! By a woman?! Imagine that. Everyone — even the New York Philharmonic, based on its 2011–12 schedule — knows that orchestra-writing is something that only men can do.

The American Composers Orchestra has created several informational YouTubes for various pieces that are to be played this evening, but NOT for Ms. La Barbara’s. (What are they hiding? Do your homework, gentlemen. That’s all I ask.) But the ACO’s program notes describe “In solitude this fear is lived,” her new composition, as “a sound painting for voice, orchestra and electronic sonic atmosphere inspired by the work of artist Agnes Martin…. [La Barbara] will create a sonic atmosphere using elements of breath and voice — both natural and electronically processed — to produce a wash of sound that will function as the primed canvas over which instrumental sounds float and interact. Mixed in stereo, this will be played back on speakers surrounding the audience. Solo amplified voice will also be part of the work, with the composer-vocalist moving freely around the audience as well. The title is taken from Martin’s journals.”

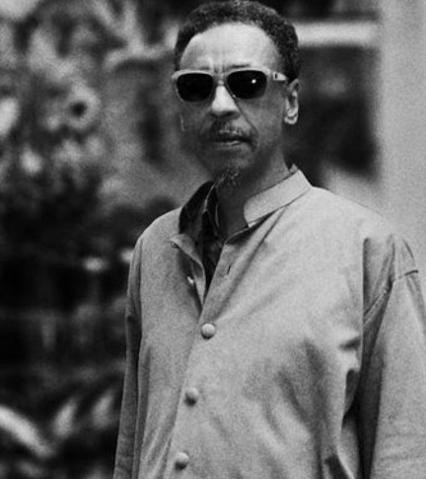

The American Composers’ Orchestra has also asked a fringe figure from the jazz world to participate in the world premiering of new music for orchestra. Henry Threadgill’s radical career stretches back to his founding role in Chicago’s Association for the Advancement of Creative Musicians (or AACM) in — of course — the 1960s. National Public Radio, naturally, has been covering his recent albums and making streams of certain songs available. Threadgill’s radical agenda of collective free improvisation is now being allowed to infiltrate the world of orchestral playing, something the composer readily admits in the following promotional videos.

The more the ACO rehearses Threadgill’s troubling music, however, you can hear how they are getting the hang of its dangerous embrace of chaos. ACO Music Director George Manahan admits as much.

There are two other pieces on tonight’s program by lesser-known insurgent leaders. One of the composers even appears to be a Millennial. And there is another woman composer on the bill.

Normally I might suggest the organization of a protest. But that might simply rally public arts supporters, or otherwise alert liberals to the existence of such concerts. (Our general success at getting liberals to pay attention to corporate entertainment through the dangling of snarkily-decorated Internet memes cannot be overstated here.) I leave it to others in the movement to debate the issue below. Consider this an open thread.

Seth Colter Walls will see you there.

England Mourns American Food Hero

I suppose we can let the Daily Mail headline speak for itself: “Dead at just 29, the 575lbs man who was the public face of high-calorie U.S. burger chain Heart Attack Grill.” They do go on though: “The larger-than-life character is famous for promoting the gut-busting restaurant in Arizona with its unhealthy menu of huge hamburgers, milkshakes and fries cooked in lard.” Flash-fried lard milkshakes! I’m in! And all this big talk from the country that invented deep-frying candy bars. For shame.

"American Masters" Subjects Ranked in Order of Americanness and Mastery

by J. Feindt

173. Greenwich Village

172. The Doors

171. Julliard

170. José Clemente Orozco

169. David Hockney

168. Man Ray

167. Yehudi Menuhin

166. Arthur Rubinstein

165. Placido Domingo

164. James Taylor

163. Milos Forman

162. Robert Capa

161. Elaine May

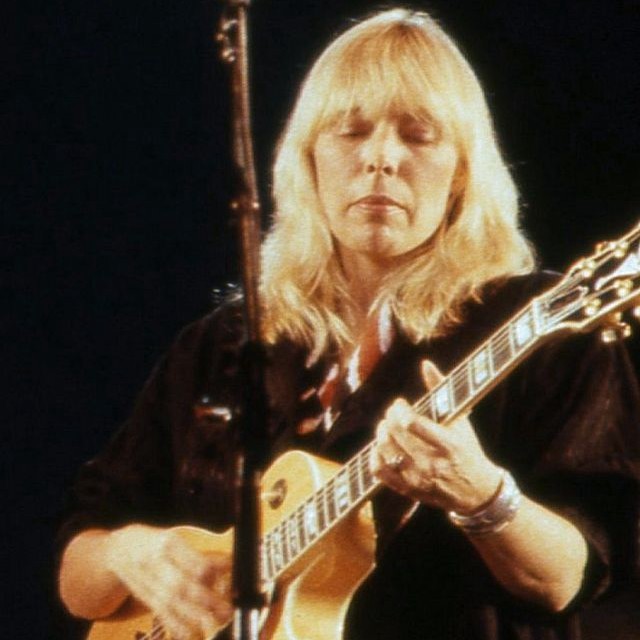

160. Joni Mitchell

159. Buckminster Fuller

158. Sweet Honey in the Rock

157. Alice Waters

156. Isaac Stern

155. I.M. Pei

154. Israel López “Cachao”

153. Glenn Gould

152. Merce Cunningham

151. Jeff Bridges

150. John James Audubon

149. Al Hirschfeld

148. Neil Young

147. Isaac B. Singer

146. Bob Marley

145. Katherine Anne Porter

144. Sanford Meisner

143. Harold Clurman

142. Helen Hayes

141. Thomas Eakins

140. Don Hewitt

139. Andre Kertesz

138. James Levine

137. Diego Rivera

136. Robert Motherwell

135. Frank Gehry

134. W. Eugene Smith

133. Lena Horne

132. Lillian Hellman

131. Group Theatre

130. Negro Ensemble Company

129. Martha Graham

128. Isamu Noguchi

127. Philip Glass

126. Benny Goodman

125. Annie Liebovitz

124. Carole King

123. Nat King Cole

122. Murray Louis

121. Alwin Nikolais

120. Cole Porter

119. Lou Reed

118. John Hammond

117. Ahmet Ertegun

116. George Cukor

115. Sarah Vaughan

114. Jerome Robbins

113. George Lucas

112. Lon Chaney

111. Albert Einstein

110. Maurice Sendak

109. Quincy Jones

108. Les Paul

107. Marvin Gaye

106. Paul Taylor

105. John Cassavetes

104. The Beats

103. Charlie Parker

102. Stella Adler

101. Actors Studio

100. Preston Sturges

99. Cary Grant

98. Sidney Poitier

97. Lillian Gish

96. Richard Avedon

95. Neil Simon

94. Paul Simon

93. Mike Nichols

92. Danny Kaye

91. Garrison Keillor

90. Muddy Waters

89. Gregory Peck

88. Carol Burnett

87. Alexander Calder

86. Charlie Chaplin

85. George Balanchine

84. William Wyler

83. William Styron

82. Billie Holiday

81. Jack Paar

80. Philip Johnson

79. Robert Rauschenberg

78. Jasper Johns

77. Aaron Copland

76. Augustus Saint-Gaudens

75. Gore Vidal

74. Norman Mailer

73. Vaudeville

72. The Warner Brothers

71. Algonquin Round Table

70. Will Rogers

69. Mort Sahl

68. Women of Tin Pan Alley

67. Richard Rodgers

66. David Selznick

65. Harold Lloyd

64. Bob Newhart

63. Billy Wilder

62. Julia Child

61. Pete Seeger

60. Sam Goldwyn

59. Alfred Hitchcock

58. Edward R. Murrow

57. Henry Luce

56. James Baldwin

55. Ernest Hemingway

54. Willa Cather

53. D.W. Griffith

52. Dashiell Hammett

51. George Stevens

50. James Dean

49. Edward Curtis

48. Georgia O’Keeffe

47. Arthur Miller

46. Elia Kazan

45. Dalton Trumbo

44. Waldo Salt

43. John Cage

42. Zora Neale Hurston

41. Eugene O’Neill

40. Judy Garland

39. Tennessee Williams

38. Hank Williams

37. Sam Cooke

36. Buster Keaton

35. Leonard Bernstein

34. Willie Nelson

33. Frederic Remington

32. John Wayne

31. Louisa May Alcott

30. Woody Guthrie

29. Truman Capote

28. Joan Baez

27. Ralph Ellison

26. Ella Fitzgerald

25. F. Scott Fitzgerald

24. Duke Ellington

23. Sun Records

22. Rod Serling

21. Alfred Stieglitz

20. Norman Rockwell

19. Martin Scorsese

18. Aretha Franklin

17. Marilyn Monroe

16. Merle Haggard

15. Edgar Allan Poe

14. John Ford

13. Gene Kelly

12. Bob Dylan

11. George Gershwin

10. James Brown

9. Lucille Ball

8. Paul Robeson

7. Andy Warhol

6. Clint Eastwood

5. Ray Charles

4. Charles M. Schulz

3. Walter Cronkite

2. Louis Armstrong

1. Tony Bennett

J. Feindt will really miss the PBS after the Republicans cancel it.

Photo by Capannelle, via Wikimedia Commons.

Why Women Have A Harder Time After A Break Up

In case you’ve forgotten, or simply never knew in the first place, the age-old question of why women take break ups harder than men do was answered with authoritative finality on this very site one year ago today. Maybe it’s time for a refresher course?

A Quiet Interlude, With Bears

Not much to see here, but I think it’s kind of relaxing all the same. Fast forward to about the 2:00 mark if you want to see the mother joined by her cubs. Anyway, these are your bears for the day. Enjoy.

People Will Smoke Anything These Days

I don’t know if it’s a desperate times, desperate measures kind of thing, but at three points in the last three days I have been stopped by strangers in the street who have asked if I have an “extra” cigarette. When offered my customary denial — a sad shake of the head, a barely audible “sorry” — each of them inquired as to whether I was going to “finish” the particular stick I was smoking. I handed it off in every case, but I find it more than a little disturbing: If New York’s vagabond inhalers are transformed into a group of irascible alcoholics through some sort of communicable breath disease, I feel like I’m going to be the one who takes the blame. Also, WTF? I’m supposed to look unapproachable, damn it! Maybe it’s time for that eye patch.

C. Dale Young, "In flagrante delicto"

by Mark Bibbins, Editor

In flagrante delicto

An itch, and then the prickly

heat, the pointed tips

at the wings’ terminus tenting

the skin between my shoulder blades.

I was so young then — the pain,

the ripping sensation and that sound

as those points compromised the

muscle, as they tore through the skin.

The wings erupted. The wings

spewed from my back. I expected

blood to splatter, but in the mirror

the tiled floor behind me

remained clean. And as the

wings extended, I saw

that the grayish feathers

were clean. No one can recreate

the panic of the first time.

Some would say I am crazy,

that this was a dream. But

was it a dream? Over a lifetime,

I have become a Master

of concealment. I have learned to tuck

the wings, learned to wear two shirts

until the wings blacken, wither, and

fall off. I don’t even know why

I am telling you this. I shouldn’t be

telling you this. But there are times

like this one where, standing naked,

I try to deploy them, anxious

to show the very things that

used to terrify me. I open

my shoulders. I lean forward. I wait.

Go ahead. Put your arms around me.

Press your warm fingers

into my back. There. Right there.

C. Dale Young is the author of three collections of poetry: The Day Underneath the Day (2001); The Second Person (2007); and Torn (2011). He practices medicine full-time and teaches creative writing in the Warren Wilson College MFA Program.

For more poetry, visit The Poetry Section’s vast archive! You may contact the editor at poems@theawl.com.

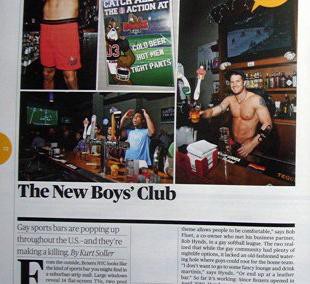

International Media Still Loving Mythical Rich Gays

They do love to make those claims still about the gays being statistically richer! Which they aren’t! For just one: “Did you know there’s a boom in gay sports bars and it’s because of our ‘disposable income’ which ‘fuels profits’? Well, that’s the claim made in Bloomberg BusinessWeek, a magazine with one of those classy Helvetica nameplates that are like catnip to urban intellectuals, so it’s gotta be true!”

Video of Anti-Muslim Protests in Southern California -- And D.C.!

Here is a video of a group of Americans who call themselves “We Surround Them OC 912,” protesting a fundraising dinner for a social services charity organization in California a couple weeks ago. The protestors should probably — among other things — read up on what they’re screaming about. (Via.)

And then there’s this.

Our Obsession with the Word "Random": Fear of a Millennial Planet

by Paul Hiebert

For a while now, something has been bothering me. It’s not particularly menacing or sinister, just annoying and unavoidable. It’s a word, and I see it in the comments section of YouTube videos and hear it from the mouths of guffawing teenage girls next to me on the subway. Sometimes it even makes an unwelcome appearance on my cell phone in the form of a text message. The word I’m talking about is random — and I’m not the only one who feels this way.

Facebook Groups have risen in opposition to this ubiquitous six-letter expression. There is “Irritated by the incorrect use of the word ‘random,’” “I HATE the word ‘random,’” “I HATE THE WORD RANDOM,” “Society against the overuse of the word ‘random,’” “Campaign against inappropriate use of the word ‘random,’” and “NOT RANDOM.”

Jackson Grant, a 27-year-old video producer from Australia, told me over the phone that he started “Australians against overuse of the word ‘random’” one day after a co-worker had responded to a joke by saying “How random!” Grant shivered a helpless shiver for the last time, and at lunch logged on to begin his protest.

This particular use of the word random has penetrated pop-culture so recklessly and so thoroughly that examples can be found in English-speaking markets all across the globe.

They include:

→ Quote from American rom-com, He’s Just Not That Into You: “I was delusional about that relationship. I used to refer to him as my husband to random people, like my dental hygienist.”

→ Title of New York Magazine online article: “Six Random Michael Jackson Pop-Culture Moments.”

→ Chorus line from British grime artist Lady Sovereign’s single “Random”: “Everybody get random/ Jus’ do sumfin random.”

→ Title of sketch-comedy series within Disney television show starring Demi Lovato, “Sonny With a Chance”: “So random!”

→ Quote from Australian mockumentary television show, “Summer Heights High”: “I’m not sitting next to some random emo!”

→ Quote from HBO’s “True Blood,” episode “Frenzy”: “A maenad, in Bon Temps? That’s random.”

→ Name of candy in the shape of several discrete objects such as bowties, sunglasses, and paintbrushes, from British company Rowntree’s: “Rowntree’s randoms.”

As an adjective, random is defined in the Oxford English Dictionary as follows: “Having no definite aim or purpose; not sent or guided in a particular direction; made, done, occurring, etc., without method or conscious choice; haphazard.” In other words, random is without pattern or objective; it’s perfectly unbiased. To judge by the pop-culture usages cited above, however, the word has shifted away from its traditional usage, and now means:

a) Inconsequential

b) Rare, strange, curated

c) Exciting, absurd, capricious

d) Unexpected, arbitrary, silly

e) Outcast, distasteful, unknown

f) Unlikely, unfeasible, impossible

g) Incongruous fun

Mark Davies, a professor of Corpus Linguistics at Brigham Young University, has created a computer database called The Corpus of Historical American English. The CoHA system searches over “400 million words of text of American English from 1810 to 2009” to “see how words, phrases and grammatical constructions have increased or decreased in frequency, how words have changed meaning over time, and how stylistic changes have taken place in the language.” It shows that random has grown in use each decade since the 1950s. Google’s Ngram book usage search shows similar results.

In 2003, Ken Ringle declared in the Washington Post that we are living in an age of random. He wondered when young people became “so overwhelmed by the randomness of the stimuli assaulting them that they selected ‘random’ as their adjective of choice.” He goes on:

Random is the flip side of that favorite slang term of post-World War II adolescent Americans: “neat.” “Neat” was the achievement (or at least appearance) of order and symmetry in one’s personal life equivalent to the butch haircuts, trimmed lawns and squared corners evanescent in 1950s public life. No loose ends left dangling. A well-tuned 1955 Chevrolet was “neat” in part because nothing about it had been left to chance.

It’s not 2003 anymore, and the age of random may be waning in 2011, but we are still living in its wake. So, what happened? How did we go from a culture of neat to a culture of random? What created this sense of chaos reigning over order? Should we blame globalization, postmodernism, the internet, or, possibly, just “Family Guy”?

* * *

I met with now-former New York Times “On Language” magazine columnist Ben Zimmer one afternoon at a coffee shop in SoHo to discuss the contemporary onslaught of perceived randomness. He is the executive producer of two language-related websites, a consultant for the OED, a graduate of linguistics from Yale, a member of the American Dialect Society and the Dictionary Society of North America, and is not a nerd, but a gentleman.

Zimmer describes the word random as a defuser of social tension, a kind of “all-purpose label” for anything out of the norm. “It has an intonation to it, a sing-song quality, so it becomes almost a refrain,” he said. “It’s interjected as a kind of meta-commentary on whatever is happening in the situation.”

Our conversation moved to etymology. When and where did random morph into these multiple new meanings?

Zimmer believes the change occurred among computer-science geeks from the late 1960s and early 1970s. In a column, “Creeper! Rando! Sketchball!.” he located one of the first colloquial uses of random in the Massachusetts Institute of Technology’s student newspaper, The Tech, from 1971. Here, the word random as an adjective meant “Peculiar, strange; nonsensical, unpredictable, or inexplicable; unexpected,” and as a noun meant “A person who happens to be in a particular place at a particular time, a person who is there by chance; a person who is not a member of a particular group; an outsider.”

After publication, he received emails corroborating his belief in random’s modern genesis. Michael Shull, a professor of Astrophysics at Colorado University, wrote that he remembers students using random in this fashion during his freshman year at Caltech in 1968. Shull said the word referred to “events that were out of the ordinary, obscure, even mysterious.” Zimmer received another email from a student who attended Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute in Troy, New York around the same time, confirming the same usage at his school.

“There obviously must have been a big influence from the more technical meanings of random and randomness coming out of probability theories, statistics, and computing,” said Zimmer. “The triumph of kids at MIT and Caltech and geek culture in general might have helped spread it, but then if you think of someone like Alicia Silverstone in Clueless, she would seem completely isolated from those cultural currents. So how do you get from one to the other? It’s hard to tell.”

There is no doubt that this usage of random has spread — and it has spread for a reason. The word’s meaning and function have merit; otherwise random wouldn’t have bridged the gap between computer hackers and Valley Girls with such success. Like neat before it, random is a word young people find accurate in describing their world. Something about it is true.

Just look at those popular Old Spice commercials featuring that shirtless, towel-clad Old Spice Guy. In what appears to be his final video, he says the advertising campaign must end because he’s too busy: “There’s giant oaks that need chainsawing into yacht boats, Bermuda Triangle mysteries that need solving with huge magnifying glasses, and everyone knows I could use one or twelve medals for winning exotic car-drawing competitions.” The clip ends with him catching a fish before exclaiming, “Silver fish hand catch.”

Or consider “South Park”’s critique of “Family Guy” in season 10’s two-part episode, “Cartoon Wars.” In part II, Cartman visits Fox studios to discover that “Family Guy” is written by five manatees, which swim around in a large tank selecting idea balls labeled with either a verb, noun or pop-culture reference. The manatees push these idea balls into a slot, where they then fall haphazardly into a container that arranges them into a “Family Guy” joke.

At one point in history, these types of narratives might have been considered stream-of-consciousness, or perhaps free-association works of art belonging in the vein of Surrealism. Now they’re just random.

“Certainly, young people are growing up in a world that accepts a kind of random clashing of ideas and concepts,” said Zimmer. “Things like online culture certainly encourage the mixing of disparate elements that would normally not go together. You could pick two songs that are stylistically different as you can imagine and then create something new out of it. Even just the experience of browsing the web is an experience where there can be a tenuous relation from one stop to the next.”

But are any of these pop-culture examples actually random in the dictionary definition of the word? I don’t think so. Despite what the observer sees, hears, or experiences, there usually is a rational process behind the apparent randomness, a method to the madness.

Imagine a Brazilian woman with an eclectic taste. She likes to watch Anime and eat sushi, listen to Frank Sinatra but not Dean Martin, and wear authentic Jil Sander coats while sporting counterfeit Gucci handbags. Let’s also say that she somehow hates every single Star Wars movie ever made — even the original three — and prefers everything Bollywood, instead.

Pretty random, right? Well, what if there is a reason behind each of her likes and dislikes? What is she spent an enjoyable year in Japan as a teenager? What if her father always danced to Sinatra in the living room, while her stepfather listens to Martin exclusively in his own bedroom? What if at some point she realized that Jar Jar Binks was no more irritating than C-3PO? If that’s the case, then nothing about her preferences is really that random. Just because the mosaic of cultural artifacts may not make sense from the outset, it doesn’t mean they lack order when her biography is revealed. No one lives outside of context. No one’s actions are devoid of intentions.

The Facebook Group “NOT RANDOM” gives a list of things that aren’t random: “That awesome outfit she’s wearing”; “Her super cool new hair style”; “The party you went to last night”; “You.”

* * *

Dr. Mads Haahr isn’t surprised to hear that the modern usage of random originates from within the culture of computer programmers and data enthusiasts, partially because he belongs to this tribe. Haahr is a professor of Computer Science and Statistics at Trinity College in Dublin, and also the operator of random.org, a website that offers a True Random Number Generator (as opposed to a Pseudo-Random Number Generator) for your lottery-ticket or password-producing needs. Haahr is dedicated to understanding both the philosophical and technical meanings of randomness. I corresponded with him via email to better comprehend our relationship to this increasingly complicated notion of randomness.

As it turns out, Haahr believes people are nearly incapable of doing anything at random because our brains are too efficient at finding patterns, at seeking links between cause and effect. He claims that if you’d ask someone to write a list of 100 random numbers, the list would likely fail a statistical test for randomness. “Randomness,” he wrote in an email, “is exactly the absence of patterns, and we have a hard time with this.”

A link Haahr posted on his website argues that since we can’t erase our memories of the past, we can never obtain the pure state of mental and emotional emptiness required to make a truly random decision. Our natural proclivities and personal histories prevent us from being without bias. “Thus,” the link reads, “it is unlikely we can meet Oprah Winfrey’s and other’s admonition to perform ‘random acts of kindness.’ We will have to settle for just ‘being kind.’”

Haahr wrote to me about the process of getting dressed in the morning:

I suspect someone who gets up and puts on random clothes in the morning just means that they don’t put a lot of thought into it. Of course this doesn’t mean that it is random in any formal sense, just that they are not conscious of the selection process. Certainly a selection process still takes place unconsciously…. I think our minds are working overtime to make sense of an environment that our improved knowledge has revealed to be more complex than we’d ever imagined.

In a sense, when a teenager deems a person or idea “So random!”, they are being dismissive of that person or idea. The teen who utters this word after being confronted with something unfamiliar — an event that doesn’t resonate with his understanding of the universe — is in a way regaining control by restoring order. What is random is folly, and therefore not a threat. In other words, it’s comforting to consider our beliefs and perspectives as logical — they make sense, after all — while any beliefs or perspectives outside of, or in opposition to our own, must therefore be chaotic, confusing, random.

“It is a way of forestalling thinking about deeper connections that might be happening,” said Zimmer. “It can be a superficial reaction to things that break the norms that you’re used to. By people using it so much you get the sense that they are encountering things they didn’t expect quite a lot, and that’s the only way they know how to react to it.”

What is dangerous about this verbal tic, this bad habit, is that it perpetuates a worldview of large-scale disorganization. Since thoughts and language are so intrinsically connected, some kind of fundamental shift is taking place in our minds through the continual maligned use of the word. I’m thinking here in terms of George Orwell’s 1984, where Newspeak leads to doublethink, or Nicholas Carr’s article “Is Google Making Us Stupid?” from The Atlantic, where Carr argues that the Internet not only alters what we think about, but how we think about what we think about. If words are the building blocks of thought, wouldn’t an abundance of random blocks result in a tendency to build random buildings?

I corresponded with Dr. Paul Horwich, a philosophy professor at NYU who specializes in Wittgenstein’s theory of language. He agrees that someone with an impoverished vocabulary will have an impoverished potential for thought, but that overall the modern usage of random isn’t that harmful.

“I don’t think you can infer from the fact that kids now use the word random a lot more than they used to, that they OVER use it,” Horwich wrote in an email. “Nor can you infer that their vocabulary is impoverished. The increased frequency in the word’s use might be due to an increased interest in randomness, and a sensitivity to it.”

So maybe things aren’t so bad. Words change in usage throughout time; that’s okay. In the Medieval period, before random meant “without pattern or purpose,” the word denoted something done “at a great speed.” Furthermore, Zimmer informed me that the entry for ‘random’ will be updated to include some contemporary definitions in the next edition of the Oxford English Dictionary. These days the anti-random Facebook Groups aren’t receiving as many wall posts as they used to.

* * *

When Ringle opened his Washington Post article with the line, “We have seen the future and it is random,” I believe he was making a moral point. The post-World War II “neat” may have been an ignorant oversimplification of the world and its inherent messiness, but the post-9/11 random is an exaggeration of this messiness and an unwillingness to find resolve or connection. There is something unthinking and uncurious and unfeeling in its use. It is defensive. It indicates a lack of empathy.

Random is anathema to synthesis through imagination, a refusal to enter the unknown.

Pascal wrote, “The heart has reasons of which reason knows nothing.” People cannot be purely rational automatons operating on a cold, dead planet. Fortuitous things happen. We give way to whim and fancy. Love exists. You can side with the reasons of the heart, or with an uncaring, indifferent randomness.

Paul Hiebert is a writer in New York.