In My Other Life

A programming note

The end of the year is here. But this year was different (just like last year and the year before), and things are dire. In times of great despair, many of us turn to fantasy.

In times like these, many of us think about our other lives—you know the ones. It could be your imagined other life, your actual secret other life, or the other life you are always planning for yourself but will never realize. Who do you want to be, where will you go when you retire (lol), what are you ashamed of having done in a previous build? Alternately, who have you been, and why did you stop being that way?

So, In My Other Life. That is the theme for The Awl’s goodbye to 2016. The package has been collected here, and features contributions by Bryan Washington, Tom Scocca, Anna Wiener, Maud Newton, Jacqui Shine, Carrie Frye, Betsy Morais, Ethan Chiel, Lindsay Robertson, Ryan Bradley, John Dziuban, Jane Hu, Rosa Lyster, Kevin Nguyen, Jo Livingstone, Miranda Popkey, Rachel Monroe, Dayna Evans, Zan Romanoff, Brent Cox and Meaghan O’Connell.

New York City, December 25, 2016

★★★★★ Shining smooth patches lay on the river, and the vent steam went in no particular direction. People ventured out onto the roof deck across the avenue and stood there for a brief while in their puffy coats. The five-year-old agreed to wear full-length track pants underneath the shorts he’d been planning to wear for the holiday. The playground was comfortable and all but vacant; the puddles were not anywhere it mattered. The five-year-old whacked tennis balls around the handball court till his head was sweaty under the hood of his coat. The direct sun and the interest in tennis eased off at approximately the same time. Tulips were out on the plants-and-flowers shelving on the side of the supermarket. The twin spires of the San Remo were lit warmly and softly by the late sun till they looked a little too real for this world.

Fundamentalist Horror Film

In my other life I do just as my parents want.

My parents didn’t agree about who I should or would turn out to be, and maybe that’s the reason I ended up disappointing each of them and going my own way. My sister and I often have this conversation: would one or both of us have wound up being who they wanted if they’d envisioned the same unthinkable path rather than contradictory ones? If we’d been brainwashed with a consistent world view? If so, hard as it was to be stuck between the two and required to pay lip service to both, I’m glad their visions were unaligned.

In one of my other lives, the one my mother planned for me, I’m a teacher at a fundamentalist Christian school that she and I founded as a companion to the church she started in our living room when I was a kid. We read the Bible and interpret its language for ourselves. Then we go out into the prisons and into the homeless shelters to take the Lord’s forgiveness, love, and salvation to everyone. We’re a tongues-speaking nondenominational outfit with a real passion for exorcisms, but we’ve borrowed lots of iconography from Judaism. In the vestibule, a shofar, ark of the covenant, and menorah stand before a dramatic burgundy velvet curtain. These remind us — and give us the opportunity to tell others — that we are “the New Jerusalem,” God’s new chosen people, the ones he was forced to choose because the first batch of chosens failed to recognize his son as the messiah.

We believe war in the Middle East is both inevitable and desirable, and that we should hasten its coming in order to hasten Jesus’ return. We voted for Trump, and we told the children at our school that their parents should vote for Trump, and of course we stopped them from drawing swastikas in their notebooks when we saw them doing it. We told them that acting hatefully toward others is wrong — even if the people are homosexuals or Muslims or otherwise the products of Satan and possessed by demons — but also that it’s not really true that people are acting more hatefully toward others since Trump won, that’s just more lies from the so-called news people who put the swastikas in the kids’ heads in the first place. We are so relieved that the world will be getting back on a more godly track now, even though Trump is an imperfect messenger. Hallelujah, Amen, isn’t the Lord mighty.

In my other other life, the one my father planned for me, I am a partner in Newton and Newton, a firm he started as a sole proprietorship when I was a kid and later turned into a partnership to include me. We specialize in international tax and advise wealthy people how to minimize their liabilities, now and at death, and we are greatly excited about the opportunities Trump’s tax code will usher in. We are based in Miami and still go to the Presbyterian Church my whole family went to for a time when I was a kid, before my mom started taking religion too seriously. We believe we were predestined for salvation, as our success shows, so we don’t need to work at it too hard. I live just a few miles from my father, with my surgeon husband and our two children, a boy and a girl, who go to the best Christian school in town. The first time my husband wanted to take me on a date, he went into my father’s study and provided his resume and family background (white, European) and asked permission. Three years later he requested my hand in marriage, and my father gave it, and then my husband asked me.

I was a virgin when we married, right after I graduated from law school at age 26. We and our extended family all voted for Trump. Although we are embarrassed by his language and his background and gaucheness, and we hope that he will be more respectful toward the constitution than he currently appears to be, obviously voting for a corrupt bleeding heart feminist like Hillary Clinton was unthinkable and it is very exciting to anticipate what Trump’s economic policies might mean for us and our clients. We aren’t at all interested in hearing about hate crimes, because we don’t belong to any of the groups being targeted. We aren’t concerned about cuts to social programs because people need to pull themselves up by the bootstraps and if they can’t make it without government assistance, well, they made their own beds and they can lie in them.

In my real life, I rejected what my parents wanted for me, or I was constitutionally incapable of being what either of them wanted, or something in between. I don’t talk to my mother about politics or religion or anything we disagree on and I am not able to talk to my father at all. But no matter how old I get, their beliefs and expectations are horror soundtracks in my mind, alternate lives I might have chosen if I hadn’t, for whatever reason, turned out to live my own.

In My Other Life, a collection of essays from writers we love, is The Awl’s goodbye to 2016.

The Record

In my other life I am trying to get it right.

Earlier this year, I interviewed the C.E.O. of a startup in San Francisco. There were two puppies in the office; their names kept changing. We were getting along, digressing. He mentioned that his favorite author was David Foster Wallace. “Yes,” I replied, “He was wonderful.” The C.E.O. paused, leaned toward me. “Did something happen to him?” he asked.

In 2016, I started talking to other people and writing about it. I do not have formal journalism training; I just like asking questions. Thankfully, people are generous. With the recorder running on the table between us, strangers talked to me about their professional aspirations and romantic histories, their childhood ambitions and adult anxieties. They revealed themselves gladly, even when they were not trying. “Everything is about my sister, really,” a middle-aged executive told me, leaning back in his chair. “It always comes back to her.”

Most of the time, though, I wasn’t talking to strangers. Most of the time, I was at home, alone. I work remotely, for a software company; at night, I switch out laptops to write. It is not uncommon for me to go a whole day without speaking to anyone. When my boyfriend comes over, it’s like flipping on the radio. But the apartment faces the street, and conversation drifts in. People hang out on the corner, playing guitar; picking fights; hawking Blue Dream, in stage whispers, to passersby. They smoke up outside the window and slouch outside an old movie theater that has been reincarnated as a modern commune catering to the digital-nomad set. When I moved in, a neighbor called them trust-fund babies. “You can tell by their teeth,” he said, rolling his eyes, “who’s had orthodontia.” The baby upstairs has been watching “The Sound of Music” for two weeks straight — I’ve never seen it, but I know all the words. I still don’t know whether my neighbor meant the homeless millennials or the communalist techies.

In the spring, a friend flew from New York City to San Francisco for a long weekend. We met in the lobby of the Museum of Modern Art, which looks like an Apple store. We stood in the “Motion Lab” and watched the Calder mobiles curve slowly away from our bodies. My friend said he was unmoved. “I feel the same way,” I lied. We stood in the middle of a circular white gallery hung with Agnes Martin paintings, those meticulous grids. I don’t know much about art or obsession, but I’ve always loved graph paper. “She never used a ruler,” a docent explained to a tour group beside us. I looked back at my friend, who was enraptured. We stood there until he was ready to leave. I tried to meditate on perfectionism. As we walked down the hall toward a stairwell, my friend turned to me. “It won’t surprise you to learn that she killed herself,” he said.

People can be wrong, and usually are. There’s so much information. Agnes Martin died in Taos, of pneumonia. She didn’t kill herself. She used a ruler — of course she did. But I can appreciate that the narrative is better, sometimes, when it’s wrong. This year, we saw misinformation operating, as they say in my industry, at scale. Did something happen to him? If you have to ask, maybe not. Maybe it’s better to live it your way. Transcribing the recordings, I sometimes observed that I, too, readily revealed myself. I wanted too much for an interviewee to like me; I wanted too much to connect. It’s all so embarrassing. Last week, I woke up to a woman shouting outside the window. “I am my own satellite,” she cried. “I am my own satellite!” What are any of us really talking about, ever? It’s only natural to get it wrong; to give too much away.

Anna Wiener is a writer in San Francisco.

In My Other Life, a collection of essays from writers we love, is The Awl’s goodbye to 2016.

If Then

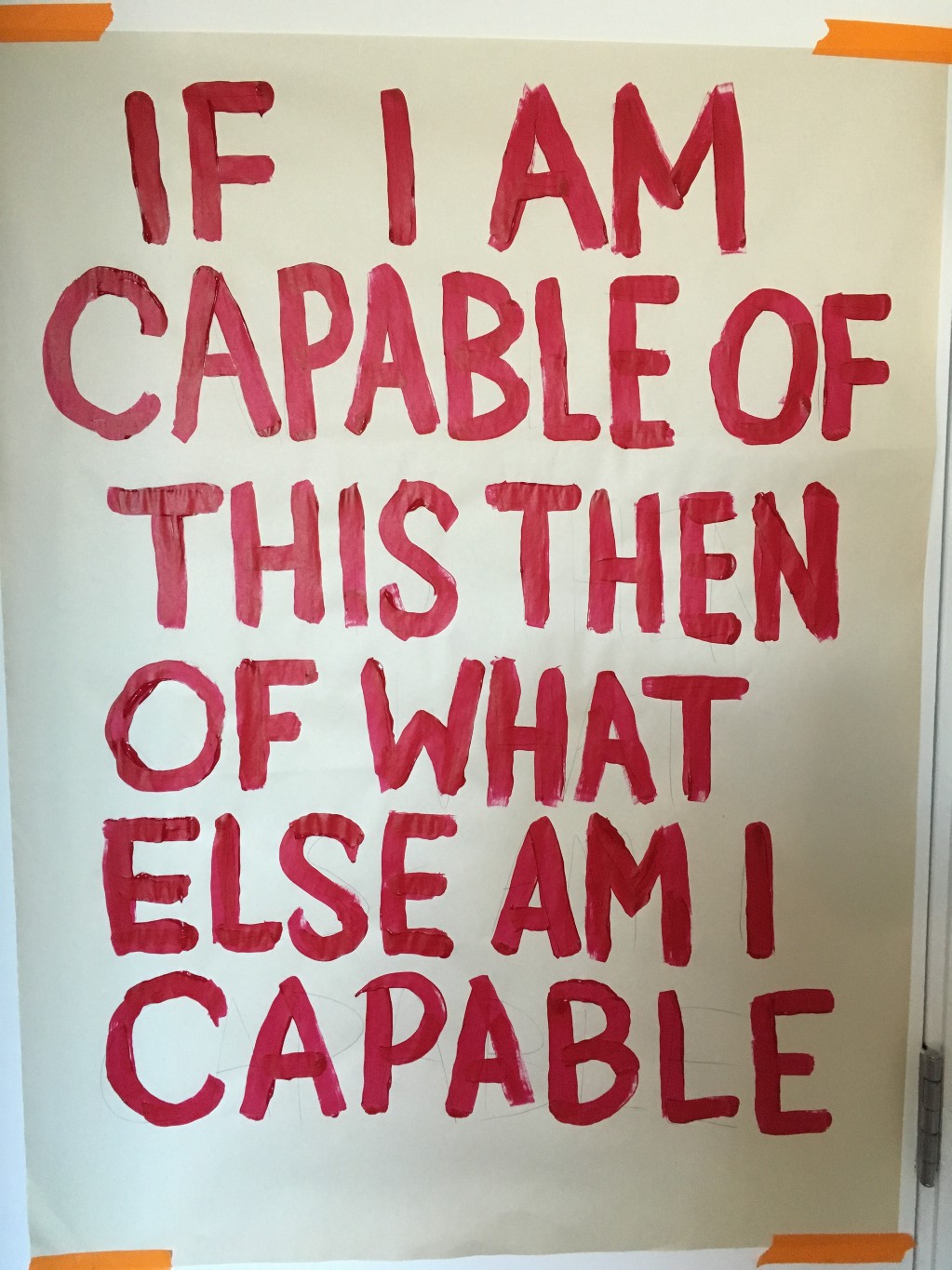

In my other life I am capable.

In My Other Life, a collection of essays from writers we love, is The Awl’s goodbye to 2016.

Tiles and Suits

In my other life I’m good at dominoes.

I know a lot of folks who’re pretty good at dominoes, but my mom is probably the best. She spends ten, fifteen, twenty minutes leaning over the table. Then she’ll lift her tile, feinting towards one end, just to slap it like a fly or a buzzer on the other. If you’ve got anything resembling an advantage over her on the board, she’ll probably talk about your mother. If you’re really far ahead, she’ll talk about your mother’s mother, too. But, mostly, she just wins, upending everyone’s drinks in the process, and it doesn’t matter because in dominoes, all that counts is the W.

When I was young, my parents threw a ton of parties. We packed our kitchen in East Texas with our Not-White neighbors — all of the Jamaicans and Cubans and Filipinos crowding the block, sipping Red Stripe and chewing coco bread and gossiping around the obvious fact of our other-ness. Eventually, someone would wonder aloud if we had a stray folding table around, and maybe a pack of dominoes in the vicinity of said table; and, at that point, one of us kids was tasked with fishing it out of the attic. The group that had fit so cleanly into suburbia slipped back into the Patois and Spanglish of their youth.

They played for hours. They’d bet paychecks and win them back. One time, some Good Samaritans called the cops on our place, swearing they’d heard a mugging or some sort of brawl. These were my first encounters with the America inside of America, the America that is America, which wasn’t Captain Planet or Britney Spears or white boys saving their dogs. Everyone left their reticence at the door, reclaiming what they’d sacrificed for their day-jobs and their neighbors, because the game brought it out in them, all of it, at once, and it felt foreign and warm and wholly familiar.

I decided that I wanted that. Whatever it was. Everything else would make sense afterwards.

There are a few things you need to be successful at dominoes, but the game’s foremost requirement is balls. That is nonnegotiable. You cannot not have balls and be a successful dominoes player, the same way that you cannot not have balls and make it as a recent immigrant in this country. So when I asked my mom, a year or two ago, how she got so fucking good, she chalked it all up to her childhood in Jamaica.

At one point, for years, she worked in a market, singing and selling off wares for tourists. She made it to Tampa from the island, back in the day, paying for every little thing on her own.

We didn’t have anything, she told me, but we had a board. So I played.

And you mastered it, I said, and my mom shook her head.

I worked all day. We played whenever.

That’s it?

You need anything else?

I told her I just thought it’d be different. And she told me that it wasn’t. They had nothing, she said, but everyone owned a board. So they made something from it. That’s what being Jamaican was.

I asked if she thought I’d ever get to that point, and she told me that it was possible. That I very well might. But I’d never had nothing. I’d never tap danced in the market for tips. I hadn’t climbed trees to pick their fruit with my bare fucking hands. A bus ferried me to school, it wasn’t sporadically closed on the whims of the government, and the word ‘hunger’, for me, was an abstract, weekend-based thing. I hadn’t grown up on the island. And it just wasn’t the same. So, no, actually, I probably wouldn’t. I didn’t have that brashness. I didn’t upturn whole counters. There was a fire in the game that I couldn’t manifest, could not conjure out of the blue, and in my bubble it wasn’t an issue, but then I’d come home and my mom would just sigh.

I remember when I realized what it could do. I was stuck with my mom and one of her friends, another thirty-ish Jamaican stuck in Houston’s sprawl. This woman usually wore her dreads long, but now they were disheveled, like she’d rushed out in the middle of an appointment and hadn’t make it back. I now know that she’d been navigating a nasty divorce, one of those irremediable affairs that fucks you up for a half-life, but, to me, back then, she just looked tired. She’d sip from her mug full of wine and laugh.

My mom and her friend touched on everything but The Problem, and after another bottle, the woman pulled some dominoes out from under her sofa. They played slowly, methodically, exchanging words every few minutes. Halfway though, my mom’s friend began to cry. Softly, and then all at once. Shoulders shaking and everything. And my mom paused, briefly, shaking her head, but after what felt like a reasonable silence she set a tile on the board.

What happened next is one of the wildest things I’ve ever seen in my life: the other woman smiled. She wiped some tears from her face. Then she jumped from her cushion, stretching the length of the board, and slammed her tile behind my mom’s yelling BOOYAKA! BOOYAKA! Then she settled back onto the pillows. My mom laughed. Her friend laughed. For a moment, it looked like they’d come out the other side.

We drove out of the city, onto the 10, and through a long stretch of nothing before I asked my mom why she’d let her win. My mom only shrugged. She said it didn’t matter. When I asked her again, she told me to please shut up.

Another thing you need for dominoes is an intellectual curiosity. Whenever I tell Americans this, there are forty-four looks they give me simultaneously. None of them is agreement. These people are generally always white. Dominoes is leaving your country in the middle of the night, with no grasp of your new nation’s language whatsoever. It’s washing dishes, for decades, for basically no pay, to qualify for loans at astronomical rates. It’s trading every visible facet of your heritage for another, molding it into an over-commercialized variant, and slipping back only in the most familiar of company, in the safety of your home, over a game of dominoes, let’s say.

The finest game I’ve seen was between my mother and her father. I’d never met him before, and didn’t think much about the fact of his existence. We were on the island for the summer, way up in the mountains, having already driven for hours, before walking who knows how far, until we ended up in this village with run-down houses and open sewage, and kids running uphill on rocks, and limbs leaning from open windows, when my mom looked up mid-stroll and said “Hey dad.”

Dude was the oldest man I’d ever seen in my life. He sat around this table with other old men, nearly identical. My mom introduced us, her family, and we shook my grandfather’s hand, and he glazed over the four of us before he turned back to the group. Of course there were dominoes on the table. My mom didn’t ask to play. She just sat right across from him and started arranging tiles. She had this look on her face, one I’d never seen before, and I haven’t seen it since, on her face, or anyone else’s.

I thought something important would happen, like he’d explain his apparent absence, or they’d fall into some sort of story, or she’d berate him for staying away. But what happened was nothing. We stood watching them play. No one said a word, and the men around us tittered.

They didn’t finish their game. I took a picture of them afterwards. My mom’s sitting in her father’s lap, shaded under a cap, smiling. Looking at that photo, you’d never know unless you knew. I kept it on a flash drive, and I kept that on a key ring, and I never had it printed it but I liked having it around.

Nine years later, moving from one shitty apartment to another, I stopped at a rest-stop, and two hundred miles later I realized that flash drive was gone. I drove all the way back. I got on my knees in this fucking bathroom. I pulled at the tile for like an hour before the cashier came in and asked me what the hell I was doing.

Once, I asked my mom if I had it in me to be a real Jamaican. She didn’t even look up when she said, Who knows, anything’s possible.

After the presidential election, but before Fidel Castro’s death, I ended up back in Texas. I didn’t want to go. I had plenty of excuses. But I showed up anyways, and the house was full, and most of the faces were familiar, all of them varying in shades of black and brown. There was a new hush, sort of, like an underlying unsettledness, one I imagine had settled over the whole county, but then my mom, if only a little quieter, asked if anyone was up for a game, and someone else yelped yes, and a table was found, and we may as well have found ourselves in another country entirely.

I sat by my mom’s shoulder while she handled the board. I was a little drunk by then. It felt nice, and I may have said so. The players spoke in patois, which I understand, but can’t speak, and for the first time in weeks just existing didn’t feel like an effort. As the game came to a close, the table turned tense, and the talk became bolder. My mom asked me to help with her hand. She wondered what she should choose, the two or the four, and I told her the two, and she said the four felt heavy. The guy on her left told her the four. The one on the right told her the two. The lady sitting across from us asked if we weren’t just cheating.

My mother looked at all of them. And then she looked at me. And she stood slowly, raising her hand, and we inhaled as it wavered.

In My Other Life, a collection of essays from writers we love, is The Awl’s goodbye to 2016.

Let Me Get That for You

The Adventures of Liana Finck

Liana Finck is a New Yorker cartoonist and graphic novelist. She posts autobiographical cartoons on Instagram.

New York City, December 22, 2016

★★★ Sinister shadowy clouds filled the view to the north, and the radar on the weather app was blue with snow outside the city. All that the dark mass produced, though, was a lumpier, paler sheet of clouds. Big birds circled under it in the distance, bracing against the wind without flapping, taut and at times held still by their relative motion. The lumps in the sky smoothed out, and brightness came in from somewhere. By the end of lunchtime, the five-year-old had bounced out of his morning sickbed and the clouds had dissolved entirely. Benevolent light shone on the rim of a trashcan and glinted off top-story Beaux-Arts window frames. The breeze down the avenue was stiff but, for the moment, still mild. That moment expired as the sun left the streets, and the wind quickly got back its bite.

Books Of The Year And How To Read Them

Yes, I do consider myself a hero.

I read fifty-eight books this year. If it sounds like I’m bragging then I have finally achieved my goal of getting my point across, since it was a very conscious effort on my part to do all that reading and I want the whole goddamn world to know about it. Because oh my God, it was work. Not that the books weren’t good — with very few exceptions, I loved everything I read — but the labor required to read a (ugh) longform piece of writing here in 2016 is so much more herculean than it was even ten years ago, given the many distractions we have these days and how truncated our attention spans are now. Would you like to hear my secrets? Well too bad, it’s my website, I’m going to share them anyway.

- Read printed books. Kindles and Nooks or ewhatevers are great, they’re very portable, you don’t have to worry about losing your page, etc. They are also connected to the greatest idiot-making poison-dispensing waste of time ever, which is the Internet. Don’t give yourself the chance to just click over “for a few seconds” and see what’s going on. You don’t need to check your mail. NOTHING GOOD IS HAPPENING ON TWITTER and you’re lying to yourself if you try to argue otherwise. If you read the Internet on the phone, put your phone in another room. Don’t look at it until you’ve finished 25 pages, or whatever amount you’ve given yourself as a minimum. Keep a pad of sticky notes and a pen with you if you think you’re going to need to write something down to look up later but do not give yourself a chance to go look it up until you are done reading, because you will never come back.

- Always be reading. Have a book ready for when you finish your current one, and as soon as you are done with the one you are reading at the present moment, start another one. Don’t give yourself an opportunity to “take a few days off to catch up on the magazines,” because you will never come back. You won’t even catch up on the magazines either, you will just read the Internet and get dumber and sadder. The Internet wants you to be book-illiterate. Don’t let it. Also, once you start the next book make sure there’s another one on deck.

- Find the half an hour a day that you are doing your dumbest, least necessary thing and use that time to read a book instead. I am almost 100% certain that you are using that half hour to do dumb shit on the Internet, but maybe you’re a big Bravo fan. Whatever it is, cut it out. Read the book instead. You’ll feel better about yourself and less bad about whatever it was you used to be doing, especially if it was watching “Vanderpump Rules” or watching people argue on Facebook.

- Keep a list of what you’ve read. This might not be all the way necessary and may only appeal to the part of the man-brain that loves lists, but there is something about the feeling of accomplishment you get in seeing the number of books you’ve completed grow larger that keeps you at it, and if you don’t maintain that feeling of accomplishment you will take time away from reading books and never come back.

Another important part of keeping a list is it will let you remember which books you’ve read over the last year, a thing that gets harder and harder to do as you age. Anyway, of the 58 books I read (that’s a lot of books, right? You’re correct to be in awe of me) a number of them were from previous years in which I was less literate (it turns out everyone was right about how good that Viv Albertine memoir was back in 2014), but there were at least five books that were published this year (or thereabouts) that were excellent and I will share them here in case you are looking for something to get you started.

Edna O’Brien’s The Little Red Chairs: I already told you about this one, here’s what I had to say.

Claire-Louise Bennet’s Pond: Same deal.

Here’s A Novel You Might Enjoy

Ruth Scurr’s John Aubrey, My Own Life: I guess I talked about books more than I thought this year.

Here’s The Hot New 17th Century Biography For Fall

Erika Robb Larkins’ The Spectacular Favela: Violence in Modern Brazil: Okay, this is sort of a cheat since it came out in 2015 but I am going to count it anyway since I’m the person making the rules and also it’s a university press book and they really need all the help they can get. This one gets a little academic in parts, and God knows ethnography has all sorts of opportunities for accusations of problematization — if there’s something particularly egregious about the volume in question please let me know, I am always willing to learn — but its lack of sentimentality and sheer on-the-ground reportage more than make up for the parts you spend yelling “Go back to grad school!”

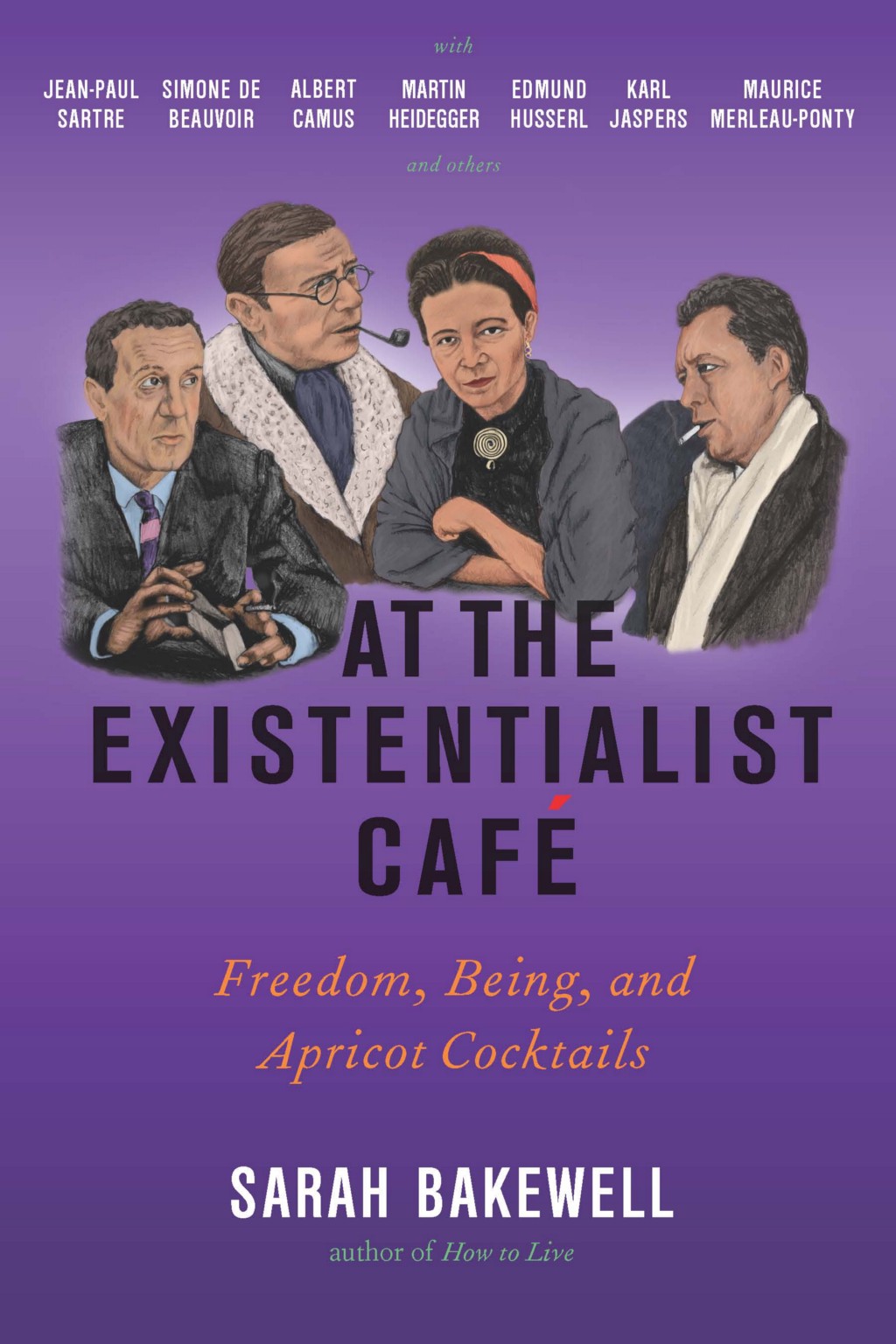

Sarah Bakewell’s At the Existentialist Café: Picture it: Jean-Paul Sartre, Simone de Beauvoir and Raymond Aron have apricot cocktails at some bar in Paris. Aron “opens their eyes to a radical new philosophical method known as phenomenology. Pointing to his drink, he says, ‘You see — with phenomenology you can make philosophy out of this cocktail!’” If this anecdote sounds familiar to you it is probably because you have read any review of At the Existentialist Café that was printed this year. They all mention it, which may have something to do with the fact that it is related right at the beginning of the book and in the accompanying press materials. In any event, this was the most delightful thing I read in 2016, because it made extremely complicated philosophy comprehensible to an idiot like me. Think of how easy it will be for you, who, except for the fact that are you still reading my post at this point, are demonstrably smarter. Beyond turning the complex, possibly nonsensical, work of Heidegger into something that does not make you fall asleep, Bakewell keeps the narrative moving along and also juggles any number of characters with ease. There is a lot of addressing the reader in this book in a way that usually makes me itch but somehow works in this case, and it is maybe the knowledge that you are in the hands of someone who has a deep affinity for the material and wants to share it with you that makes the whole thing so appealing. Anyway, if this is the sort of thing that sways you, the New York Times also named this one of its best books of the year and they read even more than 58 books. 58 is still pretty impressive though.

Tell you what, order these five titles now and get yourself set for 2017. With the world set to end at some indeterminate point it will be good to have a couple a books by your side as you wait for the radiation poisoning to do its work. Happy reading!

Things I Read This Week And Liked

Friday reading roundup.

It is here that the contemporary remix of that Elvis song “A Little Less Conversation” begins playing. Yes, that version you’re thinking of. Jim plays a Dance Dance Revolution ripoff with some holograms, wolfs down food from the ship’s fanciest restaurants, and stops shaving. After roughly one year of montaging, Jim decides that the ship’s many delights are no fun when alone. So he wanders into the spacewalk chamber and contemplates having a little less conversation, and a little more suicide. Unable to pull the trigger (or, in this case, a push a button that opens a hatch that would suck him out into space), Jim returns to the room filled with hibernation pods, trips on an empty liquor bottle, and falls at the foot of a pod inhabited by a woman named Aurora (Jennifer Lawrence). After looking at her sleeping, might-as-well-be-dead face, he becomes hornier than he’s ever been. This is the Passengers idea of a meet-cute.

Imagine if you woke up this morning and Disney’s 1998 animation A Bug’s Life did not exist. After endlessly scouring the internet, you’d come up with nothing, despite your own distinct memories of a bunch of ants going on wild hijinks through the undergrowth. You’d turn to your best friend, your brother, your mum, and say, “Hey, remember A Bug’s Life? It was about ants”, and your friend/brother/mum would turn to you and says: “No, darling. You’re thinking about Antz.”

This is how those who believe in the “Sinbad genie movie” feel when people say they are simply getting confused about Shaq’s Kazaam.

The movie that doesn’t exist and the Redditors who think it does | Amelia Tait for New Statesman

As my dear, soon-departing president well understood, in this world there is only incremental progress. Only the willfully blind can ignore that the history of human existence is simultaneously the history of pain: of brutality, murder, mass extinction, every form of venality and cyclical horror. No land is free of it; no people are without their bloodstain; no tribe entirely innocent. But there is still this redeeming matter of incremental progress. It might look small to those with apocalyptic perspectives, but to she who not so long ago could not vote, or drink from the same water fountain as her fellow citizens, or marry the person she chose, or live in a certain neighborhood, such incremental change feels enormous.

On Optimism and Despair | Zadie Smith for The New York Review of Books

Moisturize your body heavily and don’t look at the Instagram accounts of people you don’t like. That’s basically all you can do.

The Year in Unsolicited Advice | Monica Heisey for Hazlitt

“I would ask people, do you think that reality TV has an impact on people?” Pozner recalled. “And a lot of the time they’d say yes. And I’d ask those same people, do you think it has an impact on you? And they’d say, ‘Oh no, no, I’m way too smart. It affects other people.’ We all think media affects everybody but us.”

When Reality TV Becomes Reality, What’s Our Next Move? | Ellie Shechet for Jezebel

Mmm, clicky: “Time” by Hootie and the Blowfish still bangs | Making Oprah