In Scotland They Use Every Part Of The Whiskey

Alcohol: It’s good for the environment! “Construction gets under way on a £60.5m biomass power plant which is set to use whisky by-products to drastically reduce Scotland’s carbon emissions. The combined heat and power plant in Rothes in Speyside will use distillery by-products to generate enough electricity to power 9,000 homes and produce animal feed.”

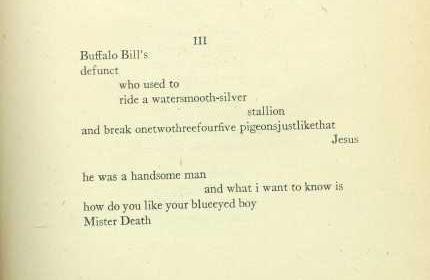

A Lost E.E. Cummings Poem Discovered

by James Dempsey

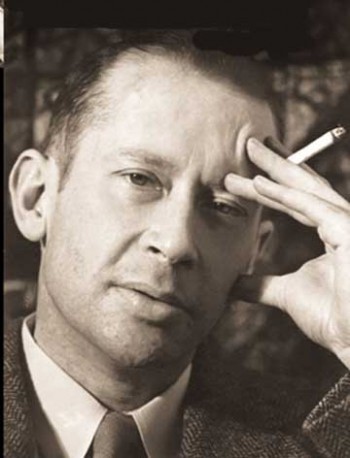

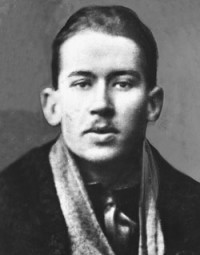

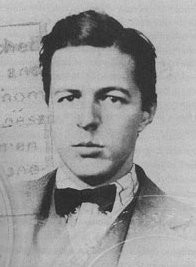

One day last year, while working on a biography of the publisher Scofield Thayer, I opened a folder of papers related to his magazine The Dial. The folder contained undated letters from the poet E.E. Cummings to Thayer, early versions of a couple Cummings’ poems and one poem by Cummings I couldn’t remember ever seeing before. It was called “(tonite” and, until I came across it, it was unknown. Evidence suggests that the poem was sent sometime around 1916, when Cummings was embarking on his career as a poet and artist. At this time the two men had known each other for about three years. Their friendship, which would last until Thayer succumbed to paranoid schizophrenia a decade later, was based largely on a shared passion for art and literature. Cummings benefited most from the relationship, as the wealthy Thayer gave Cummings money to write and paint, launched his career with publication in The Dial, and blithely assented to Cummings romancing, bedding (and, as it happened, impregnating) his beautiful wife.

The friendship had begun when, a century ago this year, a young Edward Estlin Cummings entered Harvard. There he met Thayer, fabulously wealthy and an influential figure on campus. Today, Cummings is widely read and anthologized, and Thayer all but forgotten. But at the time, Cummings looked upon Thayer as a mentor. The first piece of correspondence between the two is a polite fan letter from Cummings regarding a poem Thayer had published in the Harvard Monthly. Fans of the poet’s later work may be amused by the letter’s excessively twee formality.

Dear Mr. Thayer,

I shall feel better when I have made trial of expressing, to you, my admiration of your poem. I shall be very proud and happy indeed when I can say the thing so completely, so purely, and with such a true and fine ring as you have said it:

‘Her body is a reed, so slender

Whereon God’s lips do blow,

And in each petty human motion

The great hymns come and go.’

If this letter needs an apology, it is that I love poetry.

Your sincerely,

E. Estlin Cummings.

After receiving Cummings’ letter, Thayer, who was secretary of the Harvard Monthly, invited Cummings to join the board. That summer Cummings visited Thayer and his family at their summer home on Martha’s Vineyard. The two also explored the seedier side of the nightlife of Boston and Cambridge. In his personal notes, Cummings described one adventure in which the pair hit it off with a couple of young women. “ST & I — 2 gals, 1 healthy and attractive, other wicked and sicklooking take us to Hotel ‘Richmond,’” he wrote. Thayer evidently had sex with his young woman, while Cummings, “afraid of disease, only went to a certain point.”

Cummings’ background was solidly middle-class — his father was first a Harvard professor and then a Unitarian minister. Thayer, by contrast and by any measure, was rich. His father, who owned textile manufacturing mills in his hometown of Worcester, Massachusetts, had died when Scofield was 17, leaving his son and only child the majority of his fortune. Thayer had no interest in running mills in central Massachusetts, an area whose cultural outlook he likened to that of an “alpine village.” He attended Milton Academy in Massachusetts, where he befriended Thomas Stearns Eliot, then earned his degree from Harvard and sailed for England, where he did postgraduate work in English and philosophy at Magdalen College, Oxford. His fellow students included Prince George of Teck and the Prince of Wales, later King Edward VIII. There he again spent time with T.S. Eliot, who was also studying at the university.

The Beautiful Ones

Thayer left England in 1915 when it became obvious that the Great War would lumber bloodily on for many years to come. He returned with Elaine Orr. The two were engaged in April, 1916, and Thayer brought his fiancée to Cambridge that spring to meet his Harvard friends. Cummings probably met her around this time, perhaps at a party hosted by Thayer following a performance of John Galsworthy’s Justice. Many were struck by her loveliness. Hildegarde Watson, a friend of Thayer’s and herself a beauty who acted in her husband’s avant-garde movies, said, “I never saw anyone prettier than Elaine.” Thayer was also strikingly good looking. Erect, exquisitely turned-out, commanding, his face had both a severity and a softness, with a bowed lip that women described as Byronic. Cummings was intrigued by Thayer’s lips, and drew his caricature many times.

Cummings was the most heavily stricken by the lovely Elaine: “I considered EO as a princess,” he wrote, “something wonderful, unearthly, ethereal, the like of which I had never seen.” So struck was Cummings that immediately after meeting her, he wrote Orr, including in the letter one of his signature hand-drawn elephants. She replied three weeks later, saying she admired the elephant, was grateful for a compliment he had paid her, and hoped to take drawing lessons from him someday. Orr’s family was prominent in Troy, N.Y., where their paper-manufacturing business had prospered.

Thayer commissioned from Cummings an epithalamion, a poem celebrating his forthcoming marriage, for which Cummings was to be paid $1,000. This was patronage, of course, a way of giving Cummings money to support himself while he wrote, drew and painted. It was the first of many gifts and gestures of support Thayer would make to his friend and to others. The poem opens with an image of infidelity that would turn out to be prophetic:

Thou aged unreluctant earth who dost

with quivering continual thighs invite

the thrilling rain the slender paramour

to toy with thy extraordinary lust,

(the sinuous rain which rising from thy bed

steals to his wife the sky and hour by hour

wholly renews her pale flesh with delight)

— immortally whence are the high gods fled?

The Thayers’ honeymoon seemed fine on the surface. The couple stayed at the palatial Potter Hotel in Santa Barbara and eventually moved into a rented house. They swam, rode, read and traveled around the state. All in all, this young, good-looking, wealthy couple seemed to be living an idyllic existence, but behind closed doors the marriage was unraveling at a calamitous rate. In his notes, Thayer described what seems like a moment of horror and desperation experienced by his bride: “E.O.’s cry at the Potter was not only the cry of the broken virgin,” he wrote, “it was also the cry of the lost soul when, driven backwards, without the strength of backbone to withstand the Devil’s push — when it feels the earth give way and only air beneath it.” He went on to describe her vulnerability thus: “The eyes opened wide like windows to break.” Thayer’s writing was often expressionistic rather than journalistic, and while one cannot surmise the specifics of what he is describing here, it was obviously a moment of shock, pain and fear for Elaine, one that drained her. “E.O. at Montecito like a snake that’s had its back broken,” Thayer wrote.

But that was not all. Another note suggests that, while still on their honeymoon, Thayer told his wife he wanted nothing more to do with the marriage and that they were to live separately: “E.O. pausing in her breakfast at Montecito looked half-sick of her evil bargain.” Their romance had begun in great passion, but Thayer seemed to recoil from the intimacies of marriage, even with a beautiful woman. Later he would write in his notebook, “Marriage occupies same relation to love as the forced activities of sinners in Inferno do to their activities in this world. Marriage is as if a profound and penetrating punishment for love.”

Elaine remained fond of Thayer, however, for many years, and even admired him for the choices he made. She would tell Cummings, “One thing I know: I owe him everything, he taught me the lesson of my life[,] gave the shaking-up of my life.”

When the couple returned to the East in June 1917, just a year after their wedding, friends saw that the relationship was undoubtedly over. Thayer set up his wife in a Greenwich Village apartment and himself moved into the Benedick, an apartment building that catered to bachelors.

Cummings came to New York in early 1918 and began escorting Thayer’s wife around town. Thayer was thoroughly sanguine about the situation and even sent a check to Cummings “for the time, energy and other things you have expended upon Elaine.” Much of the speculation around Thayer has been that he was homosexual, and that this accounted for his failed marriage. While there are a few suggestions of homosexuality in Thayer’s private writings, there is much more evidence that he enjoyed a vigorous heterosexual life in line with his adoption of the philosophy of free love: “Love should be free,” he said, “and a mere social institution should not interfere with sexual adventure.” Thayer’s wife and Cummings were certainly acting on this directive; by 1919 they were intimate. Cummings, however, was not so detached in his philosophy of love as Thayer, and was fated to be utterly obsessed with Elaine. He wrote close to one hundred poems to her, including his longest poem, “Puella Mea,” and his notes are full of references to her and to his fascination with her. Through all of this, the two men remained friends, even escorting Elaine together on nights out on the town.

In 1921, the Thayers went to Paris for a quickie “French divorce,” and Cummings finally married his muse Elaine in 1924. Unfortunately, this union was even more short lived than the one with her first husband. Just three months after Cummings’ father had married the two in Cambridge, Elaine announced that she had met someone else and wanted a divorce. Her new love was Frank MacDermot, a senior partner in a firm of merchant bankers. Nancy, the daughter of Cummings and Elaine, would grow up in Europe believing that her father was Thayer, and only when she herself was a mother would she find out, from Cummings himself, that Cummings was in fact her biological father.

Bounding Toward The Pantheon

By late 1919 Thayer had become the owner, along with his friend James Sibley Watson, of The Dial, a magazine that had recently moved from Chicago to 152 West Thirteenth Street in Greenwich Village. The magazine, despite some progressive stances on political issues, had a reputation for staidness. Thayer, by introducing to its pages Modernist and avant-garde work from Europe to America, much of it aimed at shocking the bourgeois, quickly made the world of art and culture pay attention to what he was doing. A list of the writers and artists featured in The Dial under its new owners demonstrates the astonishing breadth of work it published. Verse by Yeats, Edna St. Vincent Millay, H.D. and James Joyce; fiction from D.H. Lawrence, Marcel Proust and Djuna Barnes; art by Picasso, Matisse and Wyndham Lewis. As importantly, The Dial also provided a forum for criticism that was taken advantage of by writers like Eliot and Edmund Wilson. Philosophical writings came from Bertrand Russell, John Dewey and Edward Sapir.

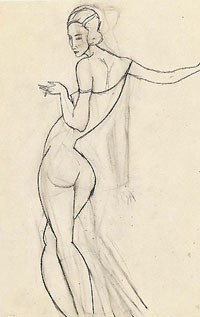

The magazine was a hit, and soon both avant-garde and traditional writers and artists were jockeying to have their material appear in its pages. Not everyone was impressed. The poet and critic Robert Hillyer wrote to a friend: “They published a perfect sheaf of awful unnameables by Estlin and some line drawings by him of trollops with their limbs spread wide apart.”

While working as an editor at the magazine, Thayer had tried to persuade the editorial staff to publish Cummings’ work, but they rejected the unorthodox experiments of the young poet. In the first issue under the new owners, however, published January 1920, Thayer thumbed his nose at the old guard by publishing seven Cummings’ poems and four of his drawings of performers at a local burlesque theater. The poet Amy Lowell, a skeptic of both The Dial and Cummings’ work, bet Thayer $100 that Cummings would not ascend to the pantheon of American poets.

The Dial’s success came at a great cost to Thayer. The magazine never made a profit, and at one point he and Watson were supporting it to the tune of $100,000 a year. The magazine made enemies, too — Ernest Hemingway was perhaps the most famous. Hemingway never forgave the magazine for rejecting his work, and accused Thayer of buggery and Thayer’s editor, Marianne Moore, of being an “aged virgin.”

Thayer also quickly found out that being forward thinking in matters of art was not without its dangers. He had to work tirelessly to ensure that the magazine did not fall afoul of John Sumner, the new head of The New York Society for the Suppression of Vice, who was successfully prosecuting and closing magazines deemed to be politically radical or immoral. Modernism itself, being an import from Europe, was often conflated in the public mind with immorality, and the vice societies were as likely to prosecute artists and intellectuals as they were the purveyors of smut. One of the more celebrated cases of the period was that of the magazine The Little Review, which was put on trial after publishing the “Nausicaa” section of Ulysses, a chapter that includes an allusion to masturbation. Thayer agreed to testify for the defense. The Dial was never prosecuted, largely because of Thayer’s genius at knowing how far he could go in publishing the unorthodox and risque.

It’s not an exaggeration to say that The Dial made Cummings’ career. For his part, Cummings recognized how lucky he was in having Thayer and Watson champion his material. He wrote his father: “I need not say that I am extraordinarily that is as usual lucky in having what amounts to my own printing-press in Thayer and Watson — by which I refer to the attention which such minutiae as commas and small i’s, in which minutiae my Firstness thrives, get at the hands of these utterly unique gentlemen.”

Through the early ’20s, as The Dial became more established, Cummings was living in an apartment in Patchin Place that was maintained and paid for by Watson. There he painted, wrote and lived a generally bohemian lifestyle that was not appreciated by all. In a letter to Thayer, Alyse Gregory, one of the Dial’s editors (she preceded the poet Marianne Moore), described Cummings’ empty apartment at Patchin Place:

[T]here are books and papers of his and a suit case and a litter of dirt which the wildest savage would blush to leave behind!! Really some men have no more aesthetic sense than certain animals I would not care to mention. Since Watson is paying for the rooms one would think that so immaculate a man as your young friend might be a little more considerate. Matches all over the floor, broken bits of glass, old orange peels — but I refrain. I am in a bitter mood.

For his part, Thayer cheerily responded: “I am astonished you should accuse the most distinguished poet of your country and generation of being devoid of aesthetic sense. Have you not seen La Vie de Bohême? Can you not admire a youth sedulously modeled upon so austere an ideal?”

Thayer’s own career as a writer never took off. His verse was awkward and antiquated, and much of his prose writings in The Dial were baroque and needlessly allusive. (His personal notes are another matter, packed as they are with apothegms and caustic descriptions of his contemporaries.) But Thayer did know how to pick a winner. That’s how he built up his magnificent art collection, most of which is now at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. He had the same touch with literature. He recognized that Thomas Mann’s Death in Venice was a masterpiece before it had been translated into English. He was the first American publisher to bring out T.S. Eliot’s The Waste Land. He wrote in The Dial the first general survey of all of James Joyce’s work to that point, from Chamber Music to Ulysses. He pointed out, correctly, that the censorship cause célèbre of the early ’20s, the trial of James Branch Cabell’s novel Jürgen, would soon be forgotten, whereas the trial of The Little Review for its printing of the Ulysses would eventually be remembered as a watershed moment in literary history. All of this demonstrates a sharp critical faculty and a sincere and aesthetic love for literature and art.

Thayer, who from his mid-twenties had been showing signs of paranoia, lived for two years in Vienna as a patient of Sigmund Freud. In 1926, he suffered a complete mental breakdown and was brought back to Massachusetts. He was declared “an insane person” in 1931 and spent the rest of his life under care. After his death, in 1982, papers and artwork were found in a storage warehouse in Worcester, including many letters from Ezra Pound to Thayer and Watson, and Picasso’s controversial painting “Erotic Scene,” which was included in last year’s Picasso exhibit at the Met.

Cummings visited Thayer in Worcester in 1930, reporting that his friend seemed a “captive of his nurses and mother.” There is no evidence of any later meeting.

Thayer pondered Cummings a great deal in his personal notes, as if trying to understand what he saw as the curious admixture of “low” breeding and lyrical genius. Here he compares Cummings with T.S. Eliot, another friend of Thayer’s who had become a literary star: “Eliot’s … repressed tones of speech are parallel to Cummings’ small I’s and to certain of his gestures and to turns of speech of his used in deflecting opposition (present or glimpsed as possible) to whatever he may be saying. All these manifestations are defensive shell formations against an environment felt as hostile.” So Thayer did not see Cummings’ much-discussed lower-case i’s as a diminution of self for the sake of humility, or modesty, or a sense of proportion, but rather as a defense mechanism, a way of making oneself small so that one is harder to observe, or perhaps, hit. In another entry, he is even more pointed: “The small I’s of Cumming are not, as he wills them, merely negative or unpicked-out. One infringes upon convention at one’s peril. This I suggests a poet very minute, very hard, very Cockney, yet very American, and having a little penetrating stink all his own.”

There is much else in Thayer’s notes pejorative of Cummings. He is a “cheap boulevardier,” “a soft-shoe poet”; he “is to Am. lit what [Al] Jolson is to Am. stage.” But the fact of Thayer’s support for (and perhaps need of) his friend right up to the end — he vainly begged Cummings to come to him in Europe when he was having his breakdown — shows another side of this complex and fateful man. In his writing, Thayer was never able to rise above his own snobbery, but when it came to what mattered — and art mattered to Thayer more than anything — he made the right choices and did the right thing.

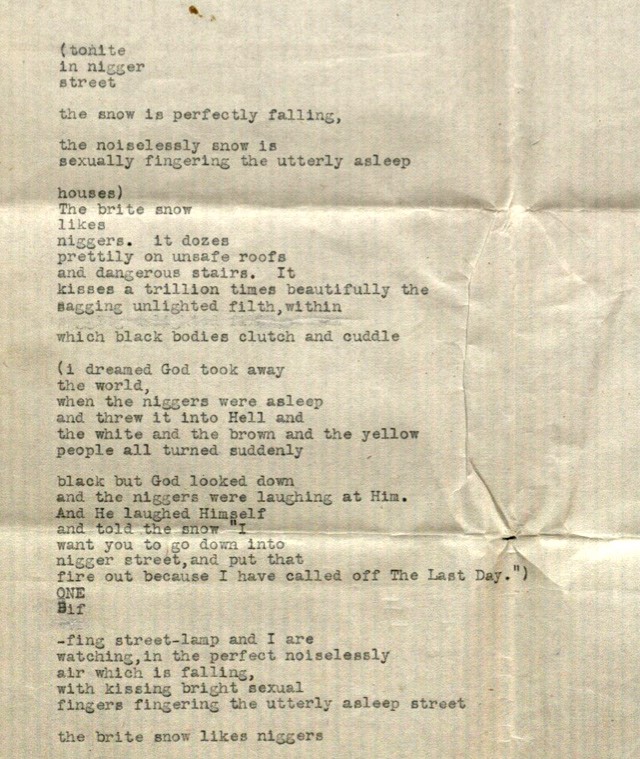

“(tonite”

I’ve been researching Thayer for about five years now, with the aim of writing a biography that would give him his share of credit for publishing The Dial. It was while researching that book at Yale’s Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, that I came across the previously unknown, unpublished poem by Cummings, “(tonite.”

The poem — which appears in full on the next page — begins with a parenthesis, which has the effect of softening or diminishing the opening lines, as if putting them into a minor key. The opening of the poem is an exposition of a snowscape.

(tonite

in nigger

street

the snow is perfectly falling,

the noiselessly snow is

sexually fingering the utterly asleep

houses)

The word “tonite” is emphasized by its spelling, by its isolation on the line, and by its primacy as the first word of the poem. This stressing of a single word is in tension with the subduing effect of the parentheses. The misspelling suggests not so much ignorance or willful illiteracy but rather the world of advertising and entertainment. It was at the time an attention-getting word one might see on a poster for a burlesque or vaudeville show. This mixing of art and popular entertainment is common in the Cummings of the period.

“Nigger” is and was at the time of writing a hard word, of course, one that was unmistakably insulting and disparaging, though not exclusively so. Carl Sandburg, by then a respected poet, had published, in 1916, a poem titled “I Am the Nigger.” That poem is sympathetic to its subject but indulges in many of the stereotypes of the African-American as being muscular, lusty, instinctual and threatening. Cummings largely avoids such stereotypes in “(tonite.” But that the word is used six times in a one-page poem perhaps gives us a clue as to why the work was never published. (This was not Cummings’ only use of the term; the word appears in at least one other poem.)

Two books of posthumous poems were published following Cummings’ death in 1962, 73 Poems and Etcetera, the latter of which, published in 1978, is almost wholly composed of uncollected poems from Cummings’ papers in the Houghton Library at Harvard. Now we have this new, unknown and unpublished text, like an echo of Modernism coming down the years, the poem “(tonite,” which shows a young writer experimenting with language and form, trying to make his words do things they had never done before. It seems appropriate — wryly so — that one hundred years after Cummings met the man who would support his art and launch his literary career, and who would share with him the woman who became his muse, that Scofield Thayer should yet again be the agent by which a poem of E.E. Cummings is published.

James Dempsey is the author of The Court Poetry of Chaucer (verse) and Zakary’s Zombies (novel). He’s also working on a biography, Tortured Excellence: The Life of Scofield Thayer.

Next: The previously unknown Cummings poem, “(tonite”.

This previously unknown E.E. Cummings poem was discovered in a folder of correspondence between the poet and his friend and publisher, Scofield Thayer. (Main story.)

© 2011 by the Trustees for the E. E. Cummings Trust. Used by permission of Liveright Publishing Corporation.

Use of archived materials courtesy of the Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Yale University.

Gaston Lachaise’s bust of Scofield Thayer on view at the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

The "The" In President Kennedy's Moonage Daydream Speech Of May 25, 1961

“But ‘the’ Earth? Why a definite article? Clearly not to distinguish the Earth from an Earth — from one of those other Earths out there. No, I suspect the purpose of that word was to distance us, however subtly, from our preconceptions.”

— The Last Word On Nothing’s Richard Panek writes an appreciative meditation on president Kennedy’s use of a precedent “the” in referencing Earth in the speech he gave 50 years ago today calling for NASA to put a man on the moon. It was pretty important!

Sit Down, Westbrook

If it were anyone other than the Dallas Mavericks — a team whose past playoff flameouts are legendary — the Western Conference championship series would be over today.

The word “devastating” is the only apt one for Monday night’s developments: Oklahoma City, at home, blew a 15-point lead with 5 minutes left and now find themselves down three games to one, teetering on the brink of losing, again, in the Western Conference Finals. They were poised to knot the series at 2–2, on the verge of overcoming what appears to be a postseason-long hierarchical rift between maybe the best player in the game, Kevin Durant, and the NBA’s fourth-best point guard, Russell Westbrook. It is almost comical watching Durant stand idly by while Westbrook fritters away the 24 second clock before vainly trying to thread the needle to Nick Collison, who is a smart player and a rugged defender, but who couldn’t finish a sentence, much less a lay-up, with Tyson Chandler on his back. James Harden has been saving the team on many nights, but now even he seems frozen out of the offense.

Okie State head coach Scott Brooks attempted to wrest the team back from Westbrook by benching him during the fourth quarter of a Game 3 victory. It was a move so courageous his nickname should be Braveheart. And, it should be noted, it resulted in a victory. Hint hint.

But Dirk Nowitzki, man. He has been so tough. And Jason Terry has hit about 300 treys from the corner. (I refuse to acknowledge J.J. Runt’s existence. His play irritates me.) They were aided, however, by Westbrook, who was back to his old tricks in Game 4: lazily defending switches, practicing his highlight-reel driving forays (unsuccessfully, I might add) and generally keeping his own offense so off-balance, it’s hard to see them threading the needle now, and winning three straight games. Especially since two are in Dallas, a team whose crowd actually seems to out-white Okie State crew of white-haired seniors. And yet … two of the games are in Dallas and that team knows from epic collapses. Whether they have one left in them is the question.

Rarely does Reggie Miller make as much sense as he did in the closing minutes of last night’s game: the Chicago Bulls were gassed. Their starters had played too many minutes and, heading into overtime they looked like Oscar de la Hoya in the 6th round versus Manny Pacquiao. Like, “Really? Another one?”

Bulls head coach Tom Thibodeau admitted as much during a timeout when he exhorted them to “push through” their exhaustion. They couldn’t and didn’t. The team’s performance was miserable during the extra period — MVP Derrick Rose played as if he had a fork protruding from his head — and the players’ complete lack of energy gave LeBron James an opportunity to practice his funny faces and dance moves for when, if he has such an occasion in two weeks, he actually wins something significant, other than a high-school championship. His behavior, even while the game was still going on, was tasteless and crass and… the crowd loved it, at least when they managed to look up from their iPhones. Former NBA Finals MVP Kobe Bryant looks like a pillar of probity in comparison. (Let me know if I need to repeat that statement for emphasis.)

The Bulls looked so beaten after the final buzzer that, like the Thunder, it seems difficult to envision them winning three straight games. While two of those contests are at home, they are facing a team that won last night with Dwyane Wade hardly contributing. Unfortunately for Chicago, Wade, unlike LeBron, has actually won an NBA championship. And you get the feeling that he will shoulder the load in Game Six, leaving LeBron more time to scowl and taunt the crowd.

God help the Bulls.

Tony Gervino is a New York City-based editor and writer obsessed with honing his bio to make him sound quirky. He can also be found here.

Photo by Keith Allison.

The 11 Most Revolting Things Sam Sifton Ate in London

Times restaurant critic Sam Sifton goes to London and what is there to eat at the hottest places in town? DISHES OF HORROR MOSTLY. A textural nightmare. A heart-stopping pile of Englishisms.

• “a plate of ‘rice and flesh’… a kind of buttery risotto Milanese, heady with saffron and studded here and there with tiny nuggets of meat taken from a calf’s tail.”

• “What you are served appears simply to be a Mandarin orange…. Cut through the dimpled skin of the fruit, however, and a mousse is revealed: an interior of whipped chicken liver with a flavor that is beautifully enhanced by the taste of its bright orange ‘skin.’”

• “a layered salad with chicken oysters (those coins of meat from behind the wings), silken bone marrow and horseradish cream.”

• “a plate of brined and hay-smoked mackerel, with lemon salad, a spray of olive oil and a ‘Gentleman’s relish’ of anchovies with garlic, milk, bread and lemon juice.”

• “juicy spiced pigeon with ale and artichoke hearts.”

• “salt-brined and long-cooked popsicle of duck leg.”

• “tipsy cake… that is a bit like a cream-filled, booze-basted monkey bread served with pineapple.”

• “sweet langoustines and unctuous yellow mayonnaise.”

• “lightly cured sea trout with pickled cucumbers.”

• “smoked pig’s-cheek croquettes with radishes.”

• “burnt cream ice cream.”

Good Lord, It's The Sun

Never have I been more pleased to see a weather forecast be wrong. It is absolutely GORGEOUS outside, New York. Go there now.

Bonnie "Prince" Billy, "No God"

The video for the new Bonnie Prince Billy song “There Is No God” is sort of like of a trip down to the Louisiana bayou from the North Carolina farm where the weird and beloved singer/songwriter filmed the video for Kanye West’s “Can’t Tell Me Nothing” with Zach Galafianakis, before the drugs wore off. It’s weird and to be loved. The song will come out on Drag City Records June 21st, with proceeds going to the non-profit organizations, Save Our Gulf and Turtle Hospital.

Where Did All of Los Angeles' Children Go? Who Cares!

“The number of children between the ages of 5 and 9 in the county decreased by 21% from 2000 to 2010” — and demographers are panicking about how that’s going to impact the local workforce in the future. But that seems a remarkably old-world way to think about population trends. This isn’t Ames, Iowa, with a brain drain and nobody about to take care of aging parents! With 15 million people in the metro area, around a city where 40% of the population is foreign-born, it’s not the children who are going to be doing the future working. It’s a city of transience and immigration, and Los Angeles has become a hub of international movement — and godless lifestyles, too, of course: “There were 32% more households with unmarried couples throughout the state in 2010 than a decade earlier.” That actually means a better future workforce, one unencumbered by marriages, unencumbered by roots. Los Angeles is becoming a city of choice.

The Heat: "America's Worst Sporting Nightmare is Coming True"

The official Miami Herald line on The Heat, in light of last night’s game 4 victory against the Bulls? “Deal with it, haters.” Okay it’s mostly over (the series is 3–1) but it ain’t over yet, and it did go into overtime, and now they’re off to Chicago, so maybe hold off just a little, Gloatsy McGloats-a-lot?

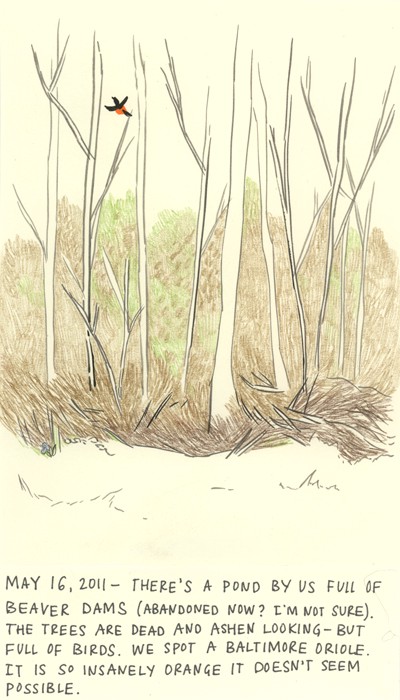

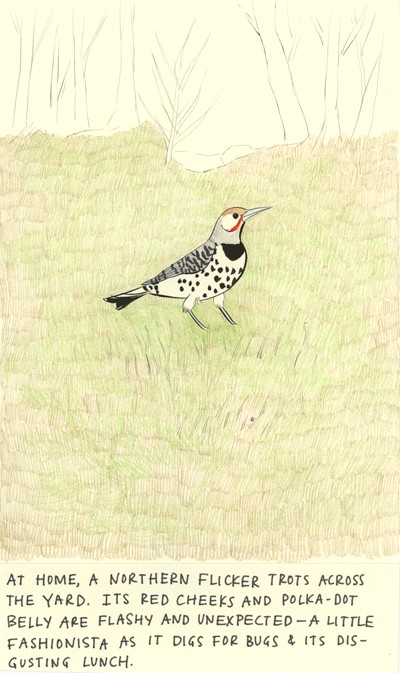

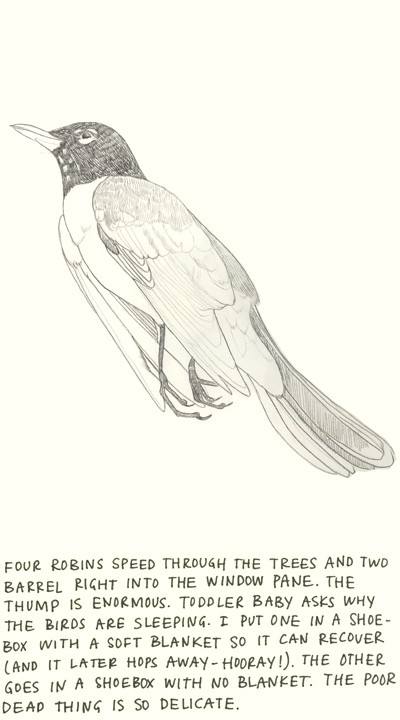

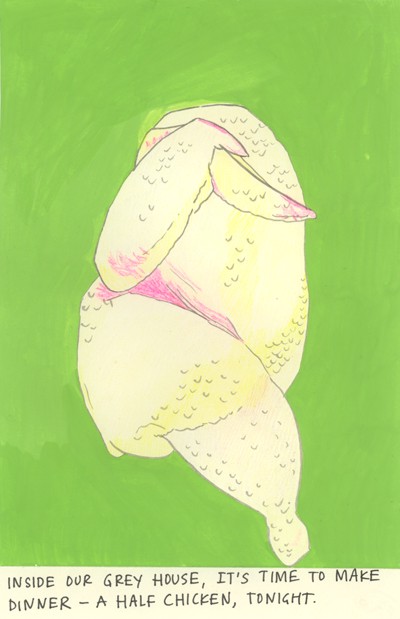

The Birds

Amy Jean Porter’s new book, Of Lamb, a collaboration with the poet Matthea Harvey, comes out next week! You can order your copy now — or, even better, pick one up at the book’s release party, which happens June 2nd, 7 p.m., at Cabinet in Brooklyn (you should go!). You can also find some nice prints by the artist here.