Boys Don't Cry

In my other life, I don’t feel pain.

One thing I remember is pitching over at the host stand of the restaurant I worked at in 2014. My ovary had a cyst, I’d learn at the ER, a place that I’d force myself to walk to, cradling my lower abdomen like, well, you know what. I remember the doctor saying that the cyst had most likely ruptured, and that there was nothing to worry about, though I don’t even remember him saying that, so much as I remember the essence of that thought, my mind steeped in a green aura. My worst bout of migraines were coming on soon, and that meant any medical calamity before them was rendered more or less inconsequential. Thinking back to a ruptured ovarian cyst now is like a memory of languishing in the Portofino sun in gingham. A dream.

This year, another friend described an experience to me that sounded symptomatically similar to my cyst. I assured her, to the best of my ability, that there was nothing to worry about. She suspiciously accepted my reassurance. I had been through the terrifying cramping and the fears that you will shatter, the wonder about whether this was what childbirth was like and if it could possibly be worth it, and I had been fine. In fact, I had basically forgotten. I had put aside that pain, tucked gently behind more severe pains, as if filing away cards in a card catalogue. I didn’t remember it until I experienced the phantom of the pain again, not long before my friend explained what she was going through. The shadow of the pain was an admonishment for arrogance. The reminder of the pain was humbling.

I have always been captivated by the ways pain is felt individually and relatively: friends of mine whose entire bodies are covered in ink were admirable. They held the scars from their labors on the surface — art and mistakes and memories they’d spend years defending until they were fed up. These friends, and friends who were visited by pain involuntarily, were a reminder of my low tolerance for pain, of pain’s commitment to making me feel small and stupid. A brag I remember hearing often from teenage girls was, “I have a really high tolerance for pain.” How could anyone know that? How could that be quantified? What if the person who walks over hot coals is less comfortable telegraphing their pain? What if they’ve learned how to properly compartmentalize what they’re experiencing? What if the world has taught them their pain doesn’t count?

This year — different from the year of the ruptured cyst, different from the year spent awake every night with migraines so severe I thought a higher power was punishing me — I felt pain, hard-to-quantify, hard-to-describe, hard-to-communicate pain. Pain brought on by an invisible force, unlike a scraped knee that bleeds or a broken arm that snaps. Internal. Inexplicable.

I saw others around me experiencing pain, too, and because of how difficult it is to really transmit your feelings to another, the world began to feel like an alienating place. The internet was riddled with attempts at destigmatizing certain kinds of buried pain — anxiety, depression, are you an introvert, did you get a bad Myers-Briggs score, are you a Virgo, does your dog not love you — but that somehow only made the isolation even more acute. If everyone is depressed, am I even depressed? If everyone has anxiety, aren’t we all normal? If you aren’t an introvert, you’re an extrovert. If you don’t talk loudly and publicly about your pain, you must not have any pain at all. Empathy is not without limits.

My only real goal for this year — the year before I turn 30, which I guess is basically as nonthreatening these days as saying the year before I turn 16 — was to find a way to understand, massage, and jettison some pain. And through that goal, I found an even deeper well: one of guilt and self-doubt, one where I knew I wasn’t entitled to a pain-free existence. I began to unthinkingly absorb suffering, compounding my own with others’, and wanting to put a soothing balm on it all. I confronted the depth the world has to foster and double pain, and in the dark, I saw my limits. I couldn’t cure anything. I couldn’t help anyone. I couldn’t even help myself. The power of relativity in people’s pain was unfathomable, and I’m sure I will never understand it.

I don’t have to imagine who I was in another life because I escape to that person often, at these moments — and particularly in this year — where nothing feels sacred, no progress possible. He is a teenage boy, running two steps at a time down a staircase, and when he reaches the end, he jumps up to the low-hanging ceiling and taps it with his hand like he’s high-fiving King James. He sweats the fear out in pickup soccer and eats half of an entire pizza because he’s “a growing boy.” He swears but no one cares, he’s kind but doesn’t have to be, and he smells sour in clothing that’s a little too big and a little too worn in. His only insecurity is over a rash of pimples covering his cheekbones. The wealth of pain in the world hasn’t reached him yet, and in my imagination, where he is safe and eternally youthful, it never will.

Dayna Evans is a senior writer at The Cut.

In My Other Life, a collection of essays from writers we love, is The Awl’s goodbye to 2016.

Drive Not Ride

In my other life, I am sturdy.

On the first day of motorcycle class, I sat next to Genevieve, my bravest friend, on a plastic chair in a classroom that smelled like industrial cleaner. Our instructor, Mike, was tan and strong-jawed, his face etched with deep lines; when he smiled, his teeth were startlingly, improbably white. He looked like a sheriff in a movie where the sheriff was a good guy. Mike asked the four of us taking the class to each identify a goal and a fear, which he would summarize and write on the white board. Troy, who managed a Flying J gas station up near the oil fields, told us he had recently bought two Harleys for $45,000 cash. This, he implied, was a great deal. His goal was to get his license, which Texas law mandated he do through this class, even though he’d been riding for years. He was unable to identify a fear. Mike wrote license on the board.

Next up was Charlie Musick, a sweet-faced Future Farmer of America from Blanket, Texas. He had ridden dirt bikes ever since he was a kid, and his goal was to get his license. His fear was that street bikes would be different from dirt bikes in ways that might catch him off guard. Mike wrote license on the board, and differences. Genevieve said that she loved dirt bikes, too. Her goal was to feel confident. Her fear was that she wouldn’t feel safe. Mike wrote confidence, and safety.

I was last. I looked at the room. I said that I had never been on a dirt bike, and had ridden on a motorcycle only once, just a few months prior, when I went on a trip around the Adirondacks with a friend, and how that time on the bike had been incredibly fun, but actually, you know, fun wasn’t really at all the right word for what it had been; it had been something altogether bigger than fun — terrifying, exhilarating — but even so, throughout the whole trip I had been uncomfortably aware of how dependent I was on my friend driving the motorcycle. My role had just been to sit there and hold on and not mess anything up, and so my goal for the class was to see if I could capture that exhilaration for myself without having to depend on anyone else, and specifically not have to depend on that person, my “friend,” since he and I probably weren’t going to see each other again for a long time, for complicated reasons I didn’t feel like getting into.

Mike looked at me for a second. On the dry-erase board he wrote: Drive not ride.

The more honest answer was that over the summer I had taken a motorcycle trip with someone I was in love with, but who was not able to love me, something that had been glaringly obvious to everyone but me. The whole thing was very sad, and left me feeling not only heart-broken but also very stupid. Afterward I was weak and wobbly for months; and then fucking Donald Trump got elected and I wondered, for the first time in my lucky, lucky life, whether the world was actually, at base, a malevolent place. In any case, it seemed smart to learn how to ride a motorcycle, in order to make speedier getaways during the imminent apocalypse. I also had the idea that this new skill would transform me into a sturdier version of myself. Women all around the country seemed to be feeling a similar urge to toughen up in preparation for the coming war — metaphorically, but maybe also literally. My friends who lived in cities were taking self-defense classes, lifting weights. I liked picturing the gang we would soon form, our leather jackets and confident swaggers. When I pictured future-me, motorcycle license in hand, I looked like the heroine of a 1980s dystopian movie: teased hair, a don’t-fuck-with-me vibe. Motorcycle Me wouldn’t have the time or inclination to lie in bed crying.

The next morning, Genevieve and I ate a pre-sunrise diner breakfast and then headed out to our designated meeting place, the high school parking lot where Mike and Troy and Charlie were waiting for us. Mike handed out helmets and gloves, then assigned us each a bike. Mine was small and red and low to the ground. I sat on it, getting accustomed to its feel, watching my breaths puff in the cold air. I felt moderately more badass already, even if I had not yet turned the thing on.

Mike’s instruction system was heavy on the acronyms: the FINE-C engine pre-start routine; the T-CLOCS inspection list. He explained how, on a motorcycle, you control the clutch with your hands and shift gears with your feet. We practiced easing into first gear and walking the bike forward; by the time we were picking up our feet and starting to ride in slow circles, the sun was up and I had taken off my jacket. The idea was that we’d soon all be moving in smooth, coordinated loops around the parking lot, but I kept stalling out and gumming up the system. Troy entertained himself by giving me unhelpful advice: You go easy at first and then when you need to, you give it more throttle. But not too early and not too late.

Once I finally figured out how to get the bike into gear, I continued to struggle. Making turns on a motorcycle requires leaning, which also means that you get closer to the ground. I didn’t like how that felt, so I kind of…didn’t lean. I was discovering how little confidence I had in the reliability of physics. “The bike isn’t going to fall over,” Mike kept shouting at me from the far side of the parking lot. I almost believed him. We practiced swerving around cones — not the traditional orange pointy kind, but little neon nipples that were intentionally small and low to the ground for safety’s sake, I realized, after I repeatedly ran them over. “That’s okay!” Mike said every time, smiling and showing his beautiful teeth. “You almost got it!”

During our break, we leaned on Mike’s pick-up ate the fun-size candy bars he bought for us. Troy told us all why he’d decided to make things official and finally get his license, after going without one for so long: He was going to ride one of his new Harleys up to Ruidoso to go gambling at the Indian casinos with his neighbor. His wife had been bothering him to get his license before the trip. His neighbor didn’t have a motorcycle license, either, but he also happened to be the local sheriff. “If we get stopped, I can probably bribe the guy,” he’d told Troy. “You can’t.”

The second day we practiced U-turns, emergency stops, and riding over obstacles. Everything was remarkably easier, as if all my anxiety dreams about shifting gears had actually helped to solidify the appropriate neural pathways. My hands and feet moved together like they were supposed to. We snaked through the parking lot with a moderate level of coordination. Mike beamed at me like a proud coach. “There you go,” Troy said, and I briefly considered running him over but decided it would be too embarrassing if I missed. By the end of the day, I felt solid in my capability to ride a motorcycle around a high school parking lot at speeds not exceeding twenty-five miles per hour. “Congratulations,” Mike told the four of us. “You are now legally permitted to drive a motorcycle in the state of Texas.”

I have had my motorcycle license for a month now, though I do not yet have a motorcycle. (Please don’t tell my mom about any of this.) Sometimes I go riding around with my friend Alan, who is trying to sell me one of the old BMWs he restores, and who has a discomfiting habit of telling me in detail about all the awful accidents he’s been in over the years: broken teeth, broken shoulders, skin scraped off, etc. But he also likes to talk about how his most beautiful memories involve motorcycles: that trip up the California coast in the 1970s; that time he and his wife rode up through Wild Rose Pass just after a thunderstorm, with the smell of creosote in the air and the post-rain wind that felt somehow scrubbed clean.

I have not, however, transformed into that sturdier and more impenetrable version of myself, the one who speeds down the highway shouting fuck you to death and danger and the possibility of being hurt. Motorcycle Me, who is tough and therefore oblivious! Or oblivious and therefore tough! Because it turns out that, for me at least, riding a motorcycle makes me feel the opposite of oblivious and invulnerable. Instead, I am hyper-vigilant about my environment, paying attention to things like the location of puddles and potholes, the speed and direction of the wind, what that 18-wheeler behind me is up to. If there’s not already a gang of Biker Buddhists there should be, because motorcycles are an excellent way to activate your awareness of the present moment — and also the constant proximity of death, and how skin is such a thin and insufficient way to keep all your important parts inside.

Does this all make it sound unpleasant? It is the best thing I’ve done in a long time. Fun is actually the exact right word for what it feels like to expose yourself to all that speed and sensory overwhelm. Why would anyone want to be invulnerable? The world comes at you very fast, and there’s no use in pretending otherwise.

In My Other Life, a collection of essays from writers we love, is The Awl’s goodbye to 2016.

> A few nice things happened this year:

From Everything Changes, the Awl’s newsletter. Subscribe here.

Last week, I shared my best of 2016 and asked you for yours. A few below, all here.

I hope all of you had at least one moment as nice as these this year, and that next year will contain even more.

Thank you for reading Everything Changes this year, and I’ll see you in 2017.

I sat with a boy I’d been crushing on, our thighs touching, as we watched cosplayers strut their stuff at a comic book convention. Which might sound trite, but we are both in our mid-sixties. I might never touch him more than that, but it’s good to know I still hope. — MLT

I think I found my calling, which is serving as a poll worker. It has put a fire in my heart for democracy and for my state (Iowa) in particular, which has laws that are designed to make voting as easy as possible for the average citizen. The work itself isn’t difficult — punch in a name to a laptop, print a sticker, initial an affidavit that the voter signs and exchanges for a ballot — but, gosh, I was good at it: fast, accurate, friendly. I was energized by how seriously our hundreds of voters took the process, and I hope I energized them in return by doing my best to make it easy, and accurate, and fair. This is such a small thing against all that has come since, but it’s not nothing. I choose to believe that it’s not nothing.

Right now at this very moment I’m in my childhood home in Michigan, the Christmas tree lights are on, my sibling is asleep upstairs, my 76-year-old mother is getting ready for aerobics and my 81-year-old dad is warming up her car for her so it’s nice and comfortable. That we are all still together, that we are happy and healthy and reasonably financially secure, that we all love each other and have the ability to spend time together is a blessing so immense I never even realized how lucky I was when I was younger — I just took it for granted for most of my life. This has mostly been a terrible year: the election, my dog dying, Prince dying, Bowie, Leonard Cohen. But that I can be home for Christmas again for another year with all of us together: this is the greatest gift of my life. — RB

Hiking a slippery path to a glacier in Norway, which I didn’t want to do but my boyfriend made me. Then stopping halfway to look around at the most stunningly beautiful place I had ever been, and at my happy, adventurous, and encouraging boyfriend up ahead, and feeling like the fucking luckiest person on the planet. Lucky to be there, lucky to have spent the past eight years with a person I am deeply in love with, who loves and challenges me, and lucky to look forward to many more of these moments. — KN

The wedding in North Carolina where I inadvertently challenged a nine year-old to a ‘Hey Ya!’ dance off in front of 200 friends and strangers. — NA

I surprised my mom with a cat in June because the year before our dog died and she still hadn’t really overcome the grief. She needed a pal to sit on her lap. His name is Mačka (Mutch-ka), which is just Slovak for “cat.” She named him that because she used to say that to her cat when she was little, using Slovak words from my great aunt. Although she was initially mad at me for bringing this cat into the home unannounced, she now loves him and all his little nuances (sticking his paws in our cereal). — RME

Watching my daughter slay her violin piece in recital. Taking a family selfie in front of the Huntington Theater in Boston, just before seeing Sunday in the Park with George. Floating around a lake in Canada on a kayak, soaking up sun and listening to stillness. Driving back to my husband’s 30-year high school reunion down a lonely country road, windows open, shout-singing “Say Hello Goodbye” by Soft Cell. — MBC

Singing “Tonight You Belong To Me” to my dying Nana in her bedroom with my mother, sister, two uncles, and her favorite stuffed Kermit the Frog. Now, when I see the posthumous meme, I imagine Nana under the black hood tempting selfishly expedient actions. It’s hilarious. — MRD

Being called up on stage to play harmonica with Frank Turner on guitar — PGB

Following a heartbreaking 2015 with a first date on a snowy night that turned into full-throttle love. — MW

In August, I finally got an update, one year after my bone marrow donation. My recipient (a pre-teen girl with leukemia) is alive and engaging in pre-transplant activities. It was the best news ever. If you are looking for an easy way to make the world a better place in 2017, please consider joining the bone marrow registry. — AV

Watching my friends’ son experience the ocean for the very first time. — AL

My second date with my now-boyfriend, in a mediocre Georgian restaurant in Coney Island: gazing across the table at him but also at the extremely loud and unpleasant live rock band playing behind him, and thinking: ‘This must be love, because it’s extremely loud and the food is bad and yet I don’t want to leave.’ — JHE

Bringing my nephew to visit us in DC, and being with him when he took his first flight on an airplane. I get so blasé about air travel but after seeing it through his eyes I have a new appreciation. I now think about him staring out the window in wonder every time I fly. — MJR

Walking out of the protected wilderness area and into an orchard filled with wild ponies on Cumberland Island. I hiked 13 miles in this prehistoric wildness with my wife and our two best friends. I’d never felt so awed by a landscape before. We sat under a live oak draped in Spanish moss with a 100 year old estate house and a marsh behind us. We all ate pasta salad out of a gallon freezer bag and split a cigarette four ways while we watched the ponies graze. — PSS

Finally caught a wave of self-love after years of paddling through choppy waters. — LJ

I went to Mexico several weeks ago with my girlfriend. It was my first time leaving the country at 35 years old. It was also my birthday weekend. On the morning of my birthday, we visited the Mayan ruins in Tulum. We started the tour in the jungle, before we reached the coast. The moment we emerged from the jungle, and the ruins appeared before us, was one of the most breathtaking moments of my life. There was definitely an intangible feeling of “bigger than us,” and yet there was a palpable feeling of the history. It also sparked a much larger passion for traveling than I had previously, and I am already looking to book a more adventurous trip soon. I am very grateful for that. — TF

When a person I was dating called my landline because I said that I loved it when people call my landline. I got anxious and hung up really fast, but it made me blush. And I NEVER blush. Here’s to more blushing in 2017.

My unconventionally beautiful and smart as a whip 24 year old daughter had previously only been interested romantically in men. She had never had a long-term relationship, in fact had barely dated and although she would never have admitted it, she was lonely and sad. It broke my heart. Early this year she met a woman and they have fallen head over heels for each other. To see my daughter being appreciated and loved in a healthy, happy relationship is by far the best thing that has happened this year! She is positively glowing and that makes this mama so deeply happy!

Waking up in a tent on a Welsh beach next to my two best friends. I swam before they opened their eyes. — SH

I found a yoga class designed for big bodied yogis. For the first time in my life I am participating in physical activity in public without shame. — RG

One night, red wine drunk, rain lashing down, cycling home on a half-broken bike from a bar in a city that’s a work-in-progress and has non-functioning streetlights and building work everywhere. Cycled into a pit, fell off my bike. Somehow, lying there in the mud, soaked to the skin, a sense of freedom and adventure and life’s infinite possibilities. Maybe that was just the red wine talking, though. — SA

The night of Game Seven of the World Series. The Cubs aren’t even my team, but I *love* good baseball — all the incredible poetry and pathos of it — and my smile got wider and wider as the game became ever more epic. Plus, I did really want the Cubs to win. By the time extra innings and rain delay rolled around, I was so excited and nervous I couldn’t sit still. Finally, they took the lead in the top of the 10th, and Kris Bryant grinned as he made the final out. The next day, I read all of those stories about brothers who had been left behind during the last World Series seven decades ago, daughters who brought a radio to sit and listen to the game at their mothers’ graves. It reminded me of everything I love about this sport. It made me feel like I was living in a special time. — SK

Thanksgiving, when my uncle played my mom’s old Rascals vinyl on the record player and my mom emerged out of the unknowable fog of her newly-diagnosed Lewy Body dementia. I was with her earlier in the year when the doctors finally named the cause of her worsening memory problems, depression, and hallucinations. A former Emmy-winning journalist, she faces the disease with grace and good humor and on occasions reveals a surprising intelligence even as it’s slowly being stolen from her. On bad days, though, she can barely finish a sentence without derailing her train of thought. I’ve mostly come to terms with the fact that I can’t turn to her for advice, or for comfort anymore. While she is still my mom, she can no longer fulfill the role of mother. Over Thanksgiving, I buckled her seatbelt, zippered her coat, and held her hand while walking along uneven ground. I am grateful for every moment. When her brother played the Rascal’s cover of “Mustang Sally,” I watched my mom snap out of whatever space dimension she was floating in to get up and dance as her sisters and brother sang harmony.

Going hiking along the edges of the vast and totally pristine Copper River Delta outside of Cordova, Alaska — where you realize that human beings just haven’t quite been able to ruin everything yet, and the rich earth, water, and life prevail because there’s just no affordable way to build a road to get there. Cheers to the earth for being able to resist us! — DH

Watching my daughter slowly make her way through a story she’d never read before. Each word sounded out, each sentence carefully spoken. And the quiet joy when she finished. — Ji

> A hopeful Saturday in June in Marin with M. The outfit he wore matched the sea, the sky, and the landscape. I remember thinking as long as I continued to know him, life could be a thing that was good.

> Catching up with a college writing professor in New York after three years. We wandered down the peopled cobblestone paths of the East Village, talking about all the smart, useless things, while the air conditioning units peppered us with staccato water droplets.

Emboldened by champagne, I climbed an extremely tall ladder onto a truly rickety roof in Bushwick on New Year’s Eve. I kissed my brand-new boyfriend at midnight while fireworks exploded around us. It was icy cold and drunk and perfect.

It wasn’t until the party moved back downstairs that I realized just how tall the ladder was, and consequently, just how afraid of heights I am. My dude stayed with me on the roof for a full hour in the freezing wind while I ugly-cried and freaked out, but I’ll be damned if he didn’t get me down that ladder (and still liked me afterwards).

Our relationship ended, quietly and mutually, a few weeks ago. But I’ll always remember that bright spot of kindness and confidence in an otherwise garbage year. How good it feels to be loved and sheltered. How meaningful to be kind in the face of the wind.

Subscribe to get Everything Changes in your inbox.

Mouth Breather

In my other life, I’m not afraid of fish.

The first day I had to myself, I bought a snorkel set at the Cost-U-Less and went to the beach down the street from our condo. My son was finally in daycare and I was supposed to be finishing a book. My husband was at work, running the bookstore on this Caribbean island, where we’ve now lived for nine months.

My British expat friends here call it “being at a loose end”; it’s why we meet for coffee some mornings and why I try to pencil the beach into my daily routine. We’re all at a loose end. I’m always asking myself what a happy, functional person would do if they had the time I had, and then I try to do it. After a few weeks things feel staid, I worry I’ve lost sight of my own personal impulses, that I’ve been following someone else’s idea of personal satisfaction, and ignore it all. I stop going to the beach, stop exercising, stop journaling, stop meditating, and then therefore stop writing and fall into despair, before I slowly add back all the bullshit, realizing it’s the striving to tick all the minor, everyday boxes that keeps me sane, keeps my brooding eye off the larger box, the what-the-fuck-are-we-doing-here-waiting-for-life-to-start box.

It was in one of those upswing weeks, a fresh-start week, a rebuilding-the-scaffolding-of-a-life week that I marched to the beach with a podcast in my ears and a snorkel set in my Baggu tote.

The ocean was completely clear, as it is every single day: a comical blue-green that’s never cold. Walking into it one cannot help but sigh and feel grateful. Lucky. Offended, almost, by the unearned perfection, the steadfastness of all this beauty. Is this it, I wonder? Putting yourself in the way of natural beauty, was it that, all along? Nature works this way for me, winning me over despite myself. If only God would, too, though I suppose people would argue that the two are intertwined. Bait and switch!

Snorkeling sounded like the right thing to do here, a “water sport.” Passive engagement — my specialty. Plus there is always something very decisive-feeling about standing up on your beach towel and marching toward the ocean, especially when the gesture involves tugging a mask over your eyes and stuffing your mouth full of gummy plastic. Mission critical: look at fish.

The snag, of course, is that every since I was a child, for as long as I can remember, I’ve been scared of the ocean. Not the water itself, and not so much that I don’t go in. It’s stuck with me like a mild social anxiety, where I can function, I’m just screaming in my head. Being afraid of the ocean always felt related to my fear of the dark, maybe they were the fear of the same thing really: murk, loss of control (or the delusion of it), being somewhere things could get you. I’d skip through the shallow parts, pulling my legs high up in the air, cling to my parents’ slippery bodies as if to avoid stepping on something spiny and poisonous.

I wouldn’t have said I was afraid of fish as a kid. Or even afraid of the water. It was a private thing, barely conscious, and always something I could transcend.

The clear water in the Caribbean, though, means I can see the fish move in circles around My ankles. What I do in the ocean is stand there, waiting for something bad to happen. I squint at the motion of light on water and wonder if it has teeth.

I try not to think about it, to remind myself I deserve to enjoy this ocean as much as anyone, and then inevitably some mass of bigger fish start flopping, coming up out of the water in arcs, splashing, making me gasp. They’re fast and focused, clearly after something. I don’t want to be in the way of them. This is when I freeze, my mind a litany of every dangerous sea creature known to exist here: lionfish, barracuda, moray eel, shark.

Even the benign fish might touch me though, might slip their gooey bodies astride mine, those horrid mouths opening and closing. This is when I scurry back to my towel, when I sit there watching the fish in their disgusting frenzy and wait for everyone else in the ocean to run out, too. They don’t. Aren’t they scared? Did they see my arms flailing as I all but flung my body on the shore? I have to keep myself from catching the eyes of all the tourists, pointing at them and shrugging.

Everyone at the beach is mellow and contemplative, just glad to be there. I can’t imagine an inner life where contemplation didn’t involve anticipating catastrophe.

You could say I’m not a beach person, though I’m not ready to. I love arriving at the beach, looking at it, hearing it, wondering what the fuck to do with myself besides sit on the beach and do whatever I’d do off the beach, except now I’m in public getting skin cancer with no wifi. So snorkeling it is.

In a way, snorkeling is preferable to just plain swimming. In snorkeling the point is to look; it’s a sport perfectly married to my paranoid vigilance. Instead of floating on my back in the sea, trying to pretend relaxation as I wait for a nurse shark to break character and attack my spinal column (“they don’t until they do,” I always want to say), I can put on my mask and breath through my mouth, and let my heart race as I look right and then left, waiting to see one before it sees me.

I know intellectually that most of the fish are harmless and moreover afraid of me. I imagine myself swatting them away, punching them in their sides. I find myself wishing I had a weapon of some kind, or a suit of buoyant chain mail. Something to make me feel more dominant. A gun? Do I want to shoot a fish? I know that I do not like being in the ocean in a bathing suit, do not like my chubby thighs bobbing in their seductive vulnerability, a siren song for moray eels, lionfish, the barb of a sting ray. I imagine them overtaking me, like Hitchcock’s Birds. Fish.

The problem is the fish are beautiful, remarkable here. I know this. I have Googled them all. I hate them but I also don’t want to be kept from seeing them because of a thing as small as fear. I want to go see fish and tell my husband about them later. I want him to second guess me and then argue with him about what I saw. I want our argument to end with me showing him a photo on the internet, to say, I know that is what I saw, and for him to say, “Okay!” I want him to say, “I can’t believe you went snorkeling all by yourself! I need to get a mask so we can go together.”

It helps me to be alone when I do new things, to operate without the context of someone to regularly turn to for assurance. “Is it on right?” “Should I put on my flippers now or in the water?”

There was no one at the beach that day who knew me, who knew how out of character it was for me to spit in my mask the way I’d seen other tourists do the day before, and so I did that, and then dove underwater without hesitation.

It did not take long for me to flipper-swim my way into marine life. Electric yellow and blue angelfish the size of my head surrounded me, like they do in cartoon movies, moving in unison and then swinging to a stop, like skiers braking at the bottom of the slope. Parrotfish, clownfish, fish with long trumpet noses and brown spots, all swam tentatively around me. I flapped my flippers, trying to splash just enough to keep them at a distance. I crept on, feeling like I had been shrunk and deposited into a pet shop aquarium, one of those tiny novelty divers you can buy as an accessory.

I had the distinct feeling that I was trespassing, and that they knew better how to maneuver themselves down here; that I was outnumbered and should they decide to, they could attach themselves to all edges of my fashion rashguard and spirit me away. I did not like this feeling, though like most unpleasant feelings I argued with myself over it. C’mon you’re being unreasonable, people snorkel here all the time, it’s literally just looking at fish, nevermind that you haven’t topped up your phone and you don’t even know the number for 911 if some creature comes and bites you with its prehistoric teeth, plus you spent 50 goddamn dollars on this snorkel set we all know you’ll never use again.

I was paddling toward shore, looking this way and that, not really committed to a direction, when a long silver-gray fish darted over to my body, swimming in parallel, under my torso. He (he was a he, there is no other possibility) was about the size of my forearm. He had big eyes, what seemed in my panic, and overbite. Barracuda. I screamed in my mask and kicked my legs in a fury and slapped the water until I washed up into the sand. Once ashore I sat there gasping, looking around, waiting to tell someone what I’d just seen. I felt like waving a red flag and urging everyone to save themselves. But no one was watching me, I was completely alone. I’d never do it again, those horrifying fish.

Now, when I’m honest, I know it could have been anything, but that night over dinner I could feel my husband questioning me, sure it was a tarpon or God knows what else. Something without teeth. I hit the table with my fist. “No! I’m sure of it.” I was feeling that it didn’t matter now did it, because a barracuda was possible, and this disgusting creature was after me. I’d invaded its space, gone against my better instincts, and he’d confirmed it for me once and for all. I’m afraid of fish. I live in the fucking Caribbean and it’s terrible and I hate it. The end.

In My Other Life, a collection of essays from writers we love, is The Awl’s goodbye to 2016.

New York City, December 28, 2016

★★ The doughy clouds held far past the time they were supposed to have dissipated, allowing shimmering patches to appear but never the sun. Sometimes blue was visible, yet not in a quarter where it would do any real good. The most a stir-crazy child could be persuaded to do was to pass a basketball back and forth outside for a few minutes, hands thrust in coat pockets till the last possible second of each exchange.

Double Life

In my other life, there is only one.

Many of us live double lives, presenting one version of ourselves to real-world intimates and another to those — friends and unknowns alike — estranged by the filters of the Internet. (In truth every interaction, online and off, provides an opportunity to dissemble, but.)

For example: A few months ago, I posted a picture of myself on Instagram in which I’m standing in front of a mirror wearing an acid green tank top tucked into worn, high-waisted jeans. “Earlier I had a lil anxiety attack,” the caption reads. “Now I’m going to see a metal show.” I can’t now remember the cause of it, but crying had been involved, certainly; some hyperventilating, too, in all likelihood. At some point, I’d started yelling at my husband because he could understand my distress only imperfectly. In short: the attack hadn’t really been “lil.” In context, the diminutive was deliberately deflationary, something between a wink and an eye-roll at my (hours) past self. Joking about the attack signaled — to me — that it had passed. Every like from followers signaled that I had handled an embarrassing episode appropriately (by brushing it off), and that I could still look cute after twenty-plus minutes of uninterrupted bawling.

My husband doesn’t use Twitter, has a limited Instagram presence, is gently baffled by the world of social media; his Internet is the New York Times and weird animal stories. To most, the self-mocking post would easily be read as an attempt to cope, but my husband was confused, hurt. My ability to pass the episode off as minor diminished the pain he had witnessed, a pain which, as someone who loves me, had pained him as well. It’s not that he believed I’d been faking my distress before, in real life; it’s that he couldn’t understand why I would fake nonchalance now, online.

A couple weeks ago, a friend and I were discussing the distance between the lives we live online and off; I found myself recapping the old disagreement, whose source I was still struggling to understand. “It’s that he doesn’t get to make fun of your anxiety,” she said, “and you do.”

Conventional wisdom has it that we curate our Internet presences to make our homes look more beautiful, our children more precocious, our relationships less fraught, our food more appetizing. And while that remains true in general — few are those who post genuinely, as opposed to ironically (which is to say performatively, which is to say not very), unflattering pictures of themselves or their lives online — social media rewards the kind of jokey authenticity that acknowledges and even inflates personal foibles and failures.

I’ve been accused of doing just that. In November, the writer Nina Renata Aron cited my work — and my Internet presence — in an essay outlining the emergence of what she called “Hot Mess Somehow Published in the Paris Review Twitter.” “I’m tired” Aron wrote

of reading the anxious apologetic essays — and tweets — of a generation of super smart women who seem to spend half of their time writing with confidence and appearing in literally the best magazines and journals in the country, and the other half pretending to be failures, broken, stained by the last shameful drops of Seamless takeout, hanging on by a fucking thread.

When the essay appeared, my best friend texted me, furious. Another friend reached out over email to see how I was doing. The force of their reactions was affirming — it’s always nice to know that your friends have your back — but also slightly perplexing. As sensitive as I am, the piece intrigued but did not pain me — in part because I appreciated the thoughtful, provocative spirit in which it was (well) written, and in part because its speculations about the reality of my life were incorrect. (The compliments Aron pays my writing probably also helped.) Whether Aron thinks I am or am not a failure, I certainly often feel like one; no part of the self-loathing I perform is pretend. What I am pretending — and in pretending, hoping for — is that I have enough distance from whatever mental health crisis I’ve most recently weathered to trivialize it.

Aron wants to “suggest that the flippant micro-chronicling of every bad mood, awkward exchange, and looming, soon-to-be-abdicated responsibility works to obscure all of the privilege, yes, but also all of the striving that got you to the big boys’ table in the first place, and to undermine your actual (often extremely good) work.” I’m with her on the obscuring of privilege. (Just now, freshly aware of that privilege, I feel deeply uncomfortable knowing my overtly personal writing is taking up any space online at all, feel uncomfortable being a distraction.) But I was always more likely to be passing a serious depressive episode off as a bad mood than I was to be micro-chronicling a simple case of the blues.

It’s this passing off that I increasingly find personally (i.e., with respect only to my own internet presence) troubling. It’s not just the fact that while lots of people deal with me in person, I’m the only one allowed to make fun of myself online. It’s not just that pretending I’m okay in Twitter’s company has not, so far, made me feel okay when I’m by myself — or even appreciably better. It’s that I’m worried the Internet is getting the best parts of me: my jokes and my small kindnesses; in short, my attention. The people I know IRL get my heart palpitations and my tears.

I’ve been thinking, recently, about what gets my attention. I can waste hours, an afternoon, a whole day, on my Twitter timeline, mentally recalibrating my position on any number of issues and emerging substantially wiser about none of them. (This is, to be clear, a function of how I use Twitter — as a scrolling slot machine whose jackpot I have yet to, will never, hit — rather than a critique of the platform itself.) What I’m doing is spreading my attention out, spreading it thin, so that after, there’s never quite as much as I need of it left over: for my husband, who would like to have a conversation with me; for my friends, to whom I owe emails; for my work, which requires sustained investigation.

I won’t pretend it’s possible — or even desirable — to collapse my two lives, the one I live in the flesh and the one I live in the digital ether. I do know that the time that goes into processing the flood of information available to me online, that goes into constructing a social media persona that’s slightly funnier, that’s slightly chiller, that gives slightly fewer fucks than I actually am and do, isn’t time I’m anymore sure is well spent. Others find the space between the real and the virtual thrilling, or liberating, or necessary. More and more, I find navigating that space makes it harder for me to figure out what I think, what I want, what I am. More and more, I find it vertigo-inducing.

Miranda Popkey is a writer based in St. Louis, Missouri.

In My Other Life, a collection of essays from writers we love, is The Awl’s goodbye to 2016.

Subject Test

In my other life, I brought the right pencil.

To apply for a doctoral program in the United States, a person takes certain examinations. The big one is the GRE, which stands for Graduate Record Examination. It’s a standardized outfit that tests “verbal reasoning, quantitative reasoning, analytical writing, and critical thinking skills that have been acquired over a long period of learning and that are not entirely based on any specific field of study outside of the GRE itself.” I took it in London, sitting in front of a computer, like when you take the theory part of the driving test.

Beyond that, certain fields and certain schools require more testing. Law has its own kind of test, as does med school. Only one university that I applied to required the GRE Literature in English Subject Test, but I took it anyway. The Subject Test is not administered via a computer, like the main GRE. It is a multiple-choice test done on paper under the gaze of an invigilator. The candidate brings her own pencil.

By the time I booked my Subject Test, there was no space to take the test in the city I lived in. But there were a few spots left at an 8 a.m. test in Leeds. Situated somewhere between the shoulders of England, Leeds was a hundred and seventy-five miles from my home. So, there was no way to take the train on the same day of the test. It would have meant getting on the train in the middle of the night. I booked a room in an ibis hotel, and planned to travel up the night before the test. The corporate style is to write “ibis” in lowercase.

I got to the ibis from the train station at maybe 7 p.m. At the time, I was working on an essay about Beowulf, sinking deep into its gloomy and beautiful world. The essay was about the way time works in the poem, its sense of history. Here’s a footnote from my Beowulf paper, justifying a reading that Hrothgar reads runes carved into this one swordhilt supposedly manufactured by giants in the poem:

[1] ‘runstafas’ would seem to suggest a written inscription, and it is obviously logically anachronistic to suggest that a common language or script would be shared by the ‘enta’ and Hrothgar, but this does not preclude the poetic suggestion that he can. At any rate, ‘sceawode’ is ambiguous.

It’s a great moment in the poem. So, I sat and read Mircea Eliade’s Images and Symbols: Studies in Religious Symbolism while eating a sandwich and drinking a beer in the ibis dining room, which was really more of a bar area, panelled in pale wood. Once I was done eating, I drank another beer and read a different book, about dragons. Where they came from, what they meant, and so on.

The next morning I woke a little before six to walk over to the exam. Years later my colleagues and I would return to that old stone building for conferences. Other test-takers crowded outside the building’s heavy wooden door. The sun was hardly up. Its light was weak and the cold old stone seemed to drink it up.

A candidate for the Subject Test must bring her own pencil, the rules dictate. That pencil must be a #2 pencil. However, in the U.K. we do not use this system of pencil classification. So, the crowd outside the test location was abuzz with discussion. Is an H.B. pencil the same as a #2 pencil? It must be, we reasoned, since that’s the ordinary type of pencil. But why would they specify the type of pencil unless the pencil was somehow unusual, not obvious? One girl had flown from Ireland to take this test. I hadn’t brought a pencil at all, having not read the instructions. I crossed the street to a nearby newsagent and bought a pencil without even thinking to ask what sort it was.

An online article tells me now that “The American #2 pencil usually lines up with the European HB grade,” although “there is no industry standard for the hardness of a lead grade and results vary from brand to brand. Japanese leads tend to be darker than their European equivalents, though they use the same system.”

The pencil conundrum didn’t matter in the end: the invigilator had spares. We filed in to sit at assigned desks. The test began. It was made of questions like this:

8. In lines 7–8, “to stand in thine own conceit” most nearly means

(A) to give yourself over to dissipations

(B) to keep yourself aloof from others

(C) to consider yourself superior to others

(D) to hold inflexibly to your own viewpoint

(E) to be duped by those who would prey upon your vanity

Each list of multiple-choice options was a glorious poem of nonsense. Every question was an anachronistic jumble, a large proportion of which was about American writers none of us had ever heard of. People in the room giggled. The testing room had a large window, paned in many rectangular pieces of glass. A leafless tree waved outside, tapping the glass occasionally like in Wuthering Heights as if to say that it saw how funny all of this was, how amusing that there is no international standard for grading how hard or soft a pencil is but that there is an alphabetized list of ways to define what John Lyly meant in the sixteenth century by “conceit.”

8 a.m. on a cold morning in 2009 feels like a long time ago, but it isn’t really. It would be interesting to calculate what fraction of the time since Beowulf’s composition has elapsed since then. Unfortunately, we don’t know when Beowulf was written, so we can’t. The time we test-takers spent laughing gently over the GRE Subject Test early on a cold northern morning seems now to have been carved out of time, pried out of history to show how there is no true scale for these things. (Like the dinner party in Tender Is The Night).

There can be no classification for meaning or pencils or the time between minds who have cared about poems. There is no real system behind the classification that turns you from a person into a doctor of philosophy or master of jurisprudence or a person who was rejected from grad school. These things are as arbitrary as the lowercase “I” in ibis. But how wonderful it is, sometimes, to stand in one’s own conceit.

Josephine Livingstone is a writer and academic in New York.

In My Other Life, a collection of essays from writers we love, is The Awl’s goodbye to 2016.

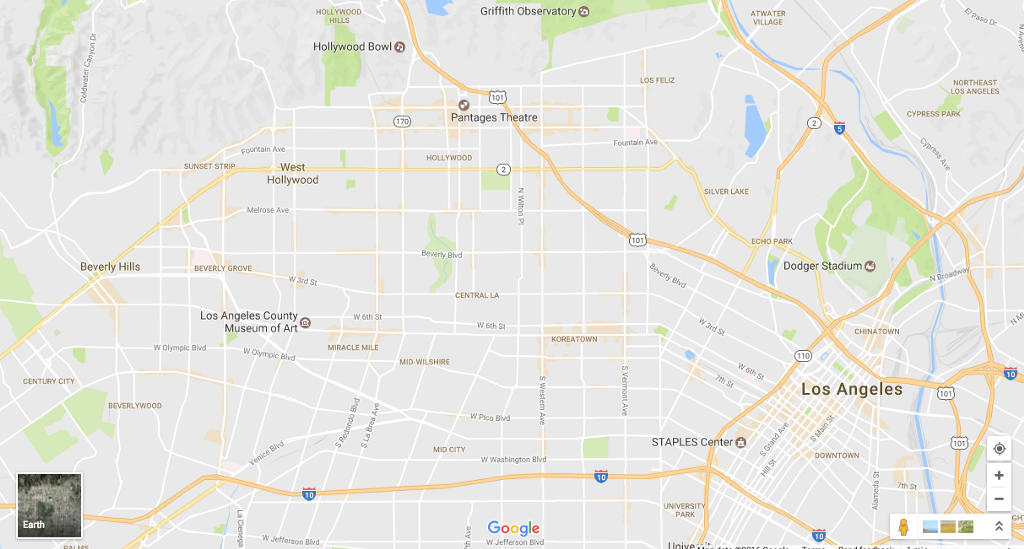

Earth Is Just One Really Big Google Map

In my other life, I know where I’m going.

The traffic is so bad in Los Angeles that Google Maps tells us to stay off the highway. I guess this is obvious to anyone who lives there, but I don’t. On my way toward Culver City from Los Feliz — two neighborhoods I wouldn’t be able to locate without Google Maps — I follow the gentle voice of a GPS as she guides me through a zigzag of backstreets, due southwest. It isn’t a bad way to see a city I’m not familiar with. I pass the shops of Koreatown, the Victorian mansions of West Adams. Because LA is a grid, its scenic route is a series of alternating left and right turns.

Every trip I take — for business or leisure — is contextualized by Google Maps. But relying on the GPS means never really getting situated. Even after I leave a new city, I feel that my spatial awareness of it is about as good as it was when I arrived. Google Maps means I’m never lost, but I never really know where I am either.

I worked full-time at Google for six months as an editor. Google makes the majority of its revenue from advertising, yet employees were reluctant to ever refer to it as an advertising company. I was told repeatedly that it was a technology company, a hub of innovation. Most of people drank the Kool Aid, except it wasn’t Kool Aid so much as lightly flavored water available in bountiful refrigerators around the office.

One day, I received a meeting invite titled “Algorithmically Generated Content.” A stranger at the company was very excited to talk to me about using computers to write content rather than relying on human beings. Like a lot of the meeting invites I received from strangers, little context was given. It was an alarming email to receive as someone who writes and edits for a living. I’d like to think that my skills can’t be replicated by a computer. But then I think about just how many computers Google has.

I later heard that the content that was being generated was for Maps. Google had acquired Zagat in 2011 to integrate the restaurant guide with the company’s location data. Apparently the integration had not gone well. Most location and restaurant descriptions were sentence fragments, written by a small team of freelancers. That was decidedly “unscalable,” and now, Google was trying to phase out Zagat descriptions and replace them with computer-generated ones. I have no idea if the computer-generated location descriptions were ever implemented. The beautiful thing about meeting invites is that they only take a single click to decline.

An incredibly popular smartphone game was released over the summer — an augmented reality game that uses real-life maps and locations dressed with an added fictional layer. As you walk around, the phone buzzes to let you know there is a cute monster you can catch. The collectible creatures can be found by roaming your local environment, which often involves bumping into other players doing the same thing. The game was built on Google Maps by a mobile gaming company called Niantic, formerly owned by Google’s parent company Alphabet. It is, essentially, a game made by ex-Google leadership on top of a Google platform, masqueraded by the license of a very popular videogame franchise.

Like most mobile games, this one is free; it makes money from its own currency. Players can use real money to buy fictional money, which can be exchanged for items in the game. Niantic has confirmed it will begin selling sponsored locations to brands as another means of revenue. The idea is that businesses can lure players to their stores and restaurants by increasing the number of collectible creatures available in the surrounding area. Niantic created the fiction that lives on top of Google Maps; they can add whatever they want to it. Soon, advertisers will be able to use real money to buy preferred placement on a fictional map that will lure players to real locations. It’s not terribly different from the way advertising works on Google Maps now. As with Google search results, sponsored slots can be bought. Through the Google worldview, all real estate is for sale.

On our last night in LA, my girlfriend and I tell friends to meet us at a bar called 4100 Bar in Silver Lake. Google Maps describes the bar as a “dimly lit intimate lounge.” I would describe it as “too crowded, too dark, and too loud.” Friends show up anyway, even though everyone seemed to know already that it was an awful bar. The next morning, I punch our destination into Google Maps. The software doesn’t recognize that the entirety of Vermont Avenue had been closed to be repaved. But no matter. We drive around a corner and the GPS voice politely explains that she was recalculating our route. Again we are instructed to avoid the highways.

I think about the trust I’ve put in Google Maps. It’s earned it, I suppose, given how much I’ve depended on it in the past decade. Four years ago, when Apple replaced its default Maps app — one that relied on Google’s mapping data — with a version backed by Apple’s own. It was a move for one tech giant to pull its reliance on a competitor. But people were outraged. I was outraged. On countless occasions, Google Maps has gotten me to where I needed to go. It has also turned me into the kind of person who gets mad about an app.

As we navigate that back roads of LA, I think about how we’re “making good time.” When I’m driving, I am always overly concerned about making good time, even though I’m not sure why. I assume Google Maps is getting us to where we need to be as quickly as possible. But do I really know that it has my best interests in mind?

One company controls the way we see the world and directs how we move through it. You have to trust that the world it presents doesn’t have other incentives or motives. But of course it does, because the reality is that Google Maps is an elaborate work of fiction — a giant framework of coded human will forced over data, some of it wrong and some of it distorted — and yet we trust it to tell us our place in the world.

Kevin Nguyen is the digital deputy editor of GQ.

In My Other Life, a collection of essays from writers we love, is The Awl’s goodbye to 2016.

A Person Of Action

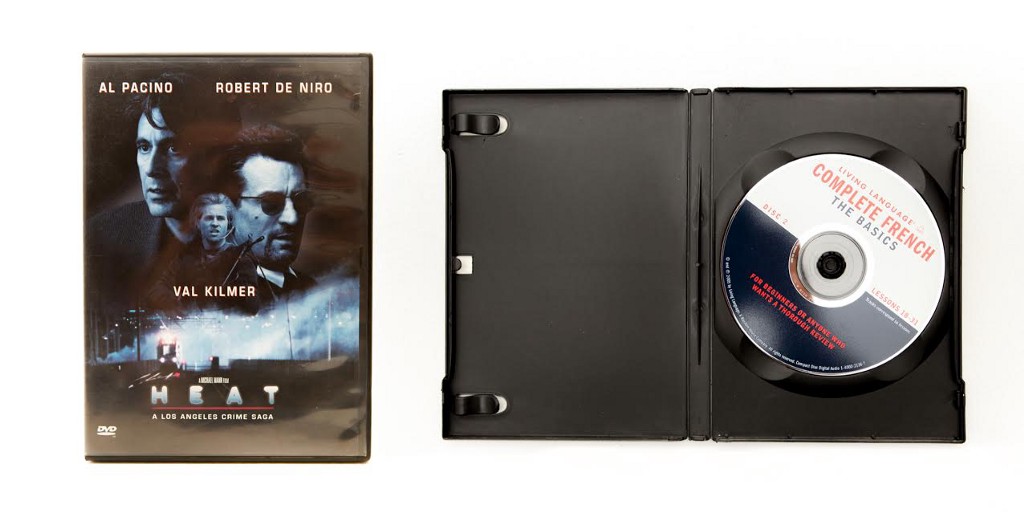

In my other life, I would understand the movie ‘Heat.’

Photos by Jarred Figgins

More accurately, I would be the kind of person who can understand the movie Heat. It has been three tries, now, and I am none the wiser. The kind of person who can understand the movie Heat is able to understand why several men with haircuts are shouting at each other and charging in and out of rooms. They are making out with women they have just met in several unsettling locations, and shooting at each other for many hours in the street. Why? To what end? I don’t know, because I am not the kind of person who can understand the movie Heat. In my other life, I would be. The knock-on effects of this would be innumerable, and they would all be good. If I understood the movie Heat, I would be efficient — a person of action, possessed of many tricks and tips regarding how best to manage her time. I would be a different kind of person altogether.

The kind of person who can understand the movie Heat is the kind of person who can listen when someone says directions, instead of hearing a kind of whistling/roaring in their ears as they wait to get it over with and then wander out lost into the world.

They can have sleeps in the daytime and wake up Refreshed instead of guilty and panicked.

They would have, in general, a healthy relationship with guilt. They would understand its uses, but it would not be the secret motivating force behind nearly everything they did.

They have no strong opinions on Shakira, either way.

They can only work at a desk, instead of sitting on their bed with papers all around like a hamster.

They regularly go to the shops to buy groceries and then when they are hungry, at home, they open the fridge and there it is: food. They take it to work in a clearly marked container.

They are patient. They are infrequent impulse shoppers. When they do succumb to the urge, they always buy the exact right thing.

They possess many chargers and double adaptors, and they have a generally respectful and calm relationship with appliances, headphones, the internet, and so on.

They do a sport.

They dress right for the weather.

They know how to make it so their car isn’t so god damn hot, a furnace with many diet soda cans on the floor.

In the movie Heat, why does Val Kilmer look so different all the time?

What happened to Ashley Judd? In life, and in that movie?

Where is that actress from? You know the one I mean.

People who understand the movie Heat either know this instinctively, which is great, or they don’t care, which is even better.

They are like this about many things. They know what is important.

They don’t care hardly at all about the princesses Beatrice and Eugenie, or Wendi Deng, or why Jerry Hall’s entire bridal party looked so fucked up. Why did she marry him. Why. Jerry, are you bankrupt or are you literally in love with Rupert Murdoch. He so old, Jerry. He so overtly sinister in every respect. Also his children definitely hate you. Why did you do this, again?

I will never stop asking these questions, because I am not the kind of person who understands the movie Heat. In my other life, I would be.

I would be good at packing.

I would never have sand in my bed.

I would have a number of clean, white t-shirts.

My New Year’s Eve plans would be good.

I would not remember with searing clarity every embarrassing thing I have ever done.

I would spend money on dumb, practical stuff such as brooms, such as a printer, such as dishwashing liquid and lightbulbs and drain cleaner, and I would not be overcome with sadness at how rubbish it is to be an adult.

When I was thirsty, I would just get up and get a glass of water instead of just sitting here, thirstier and thirstier, waiting for something indefinable to change.

I would be ready for anything.

I would never sit against a wall at a party with a hard plant digging into my back, too immobilized by shyness and discomfort to move.

I would understand the rules of football, cricket, and the road.

I would understand the movie Heat, and how a person goes about having a pristine life, everything neat and ordered and in rows, and I would not project so remorselessly onto other people, telling myself that their ability to understand a long, long police procedural which is not even amazing is somehow indicative of innate superiority, of great wells of inner resilience and peace.

I really understood nothing of that movie at all.

I was looking at the Wikipedia summary on my phone while I was watching, even.

Still.

Nothing.

In My Other Life, a collection of essays from writers we love, is The Awl’s goodbye to 2016.

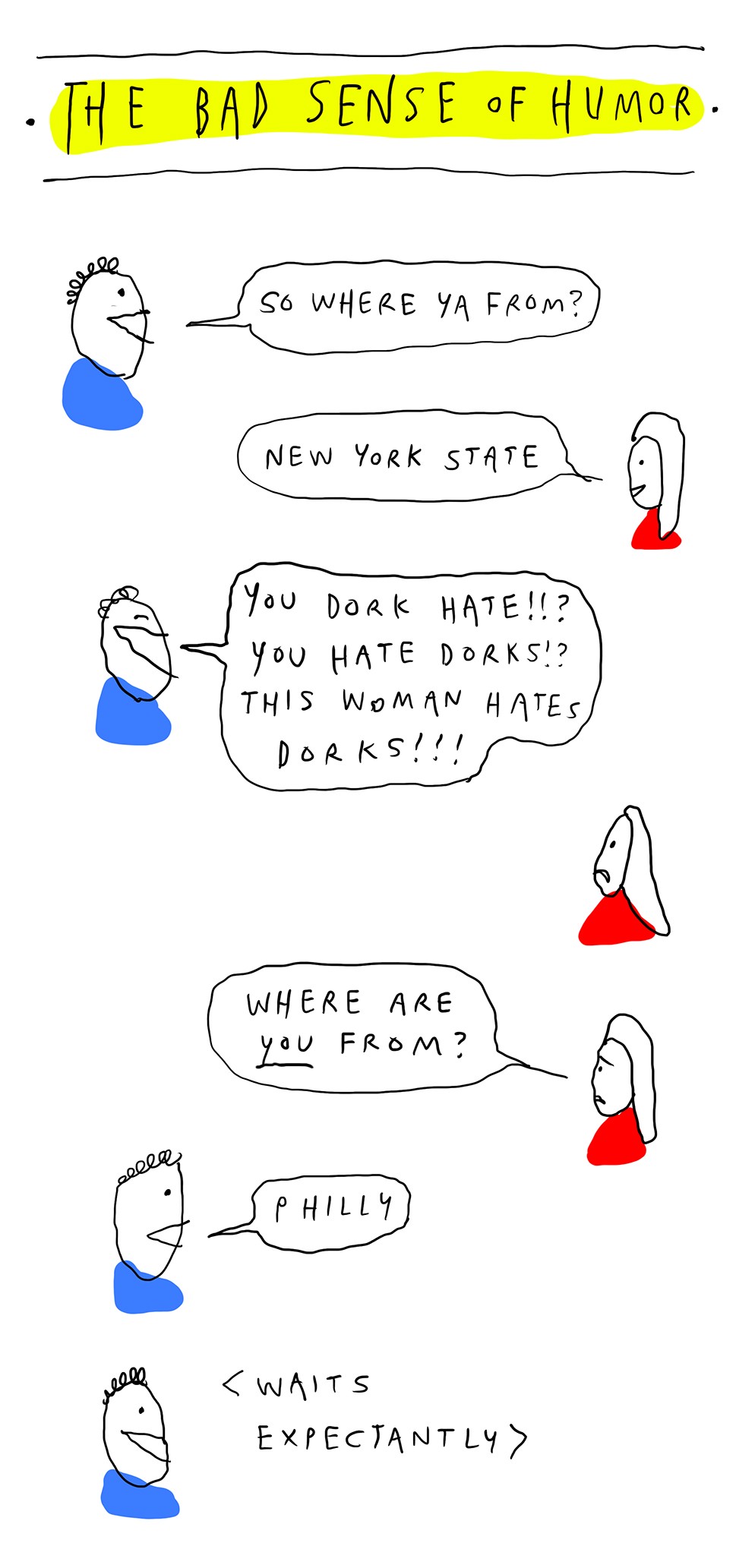

The Bad Sense Of Humor

The Adventures of Liana Finck

Liana Finck is a New Yorker cartoonist and graphic novelist. She posts autobiographical cartoons on Instagram.