Translating César Aira: A Q. & A. with Rosalie Knecht

by Alicia Kennedy

In 2006, Rosalie Knecht graduated from Oberlin and flew to Argentina on a Fulbright scholarship to work on a translation of César Aira’s The Seamstress and the Wind, out this week from New Directions. The novel is Knecht’s first as a translator, and working on Aira places her in the company of such respected names as Chris Andrews and Katherine Silver.

This is the fifth Aira novel that New Directions has brought out, and last year Barbara Epler, the publishing house’s editor in chief, told GQ that after Roberto Bolaño, Aira would be the next big success-in-translation.

It’s hard to argue with that prediction when you know a little about Aira and his vast output of very short, exceptionally weird novels. The exact number he’s published since starting his career in 1975 is unknown — he purposely publishes them with tiny presses, forcing his readers to seek them out — but it’s probably around 70. The ones available in English are also among the most original books you could hope to pick up.

To be this productive, one obviously needs a method, and knowing Aira’s is essential to understanding his work: He goes to cafes in Buenos Aires daily to write a few paragraphs by hand, and he never edits. The process has been called a “flight forward,” and it’s a good description. Reading Aira you’re on that trajectory, propelled by his audacity and playfulness. His writing lacks self-consciousness, though he is always present in the novels — whether as a character named after himself or through the inclusion of lengthy philosophical non-sequiturs. Each book is set to destruct around the 100-page mark, after taking numerous, fitful turns across genres.

In The Seamstress and the Wind, the author is more present than ever. The novel begins with Aira in a Paris cafe, discussing his desire to finally write the novel with this great title that’s stuck with him. He moves on to the nature of memory and travel before steering into what could be a traditional narrative about the mother of his childhood friend following her supposedly lost child into “the land of the wind,” Patagonia. The wind initially seems to represent fate, but as the action moves south, it becomes more of a presence until it is speaking and then suddenly a character. It’s clear in the novel that Aira considers himself a literary seamstress moved by the wind, but then what does that make his translator? To get some insight, I interviewed his engaging translator, Rosalie Knecht, by email.

Literary translation is kind of mysterious. Your name gets printed very small on the title page, and the general perception is that you’re supposed to be invisible. What attracted you to it?

It actually seemed kind of glamorous to me. It allows you to participate in someone else’s work in a very intimate way. By the end of it, you know the meaning of every single word. You’ve pictured every single object.

I met César Aira a few times while working on the translation, and I remember using words in conversation that I had learned from his book. So I wanted to do translation because it’s another way to participate in fiction. A more literal answer is that I majored in Spanish in college and I was applying for a Fulbright and didn’t know what to propose for my project, and a professor suggested translation. I hadn’t thought of it myself because it seemed kind of audacious. It involved sending a letter to this literary figure, trying to strike the right tone of confidence and extreme, cowering politeness. And then Aira wrote me back all casually, like “Yeah, sure, whatever. When are you going to be in town?”

In interviews and in his work, he comes across as someone who would respond like that and just be totally open. So why did you choose him, and why this novel?

I read How I Became a Nun first, and loved it. For those who haven’t read it (spoilers!), it’s about a six-year-old girl whose father murders an ice cream vendor and is sent to prison. At the end of the book, the child is drowned in a vat of strawberry ice cream by the vendor’s widow. Taken like that, the book sounds just kind of whimsical, or maybe a little too clever, but actually it’s extremely weird, for two main reasons: 1) it’s in first person, but the protagonist dies at the end at only age six, thereby never becoming a nun, negating not just the title but the general tone of wistful adult remembrance that the whole novel is told in; and 2) the child switches genders halfway through, first referring to herself and being referred to by those around her entirely in female terms (which is pervasive, this being a language where every adjective confirms the gender of its object) and then in male terms, and no one refers to this change at all, including the narrator. Also, the little girl/boy is named César Aira, but that’s not such an unusual ploy these days.

I liked it because it seemed genuinely, profoundly weird. A lot of literary fiction feels defensive about whether it’s interesting enough plot-wise, so it overcompensates by being all about flashy genre set pieces and talking frogs that solve mysteries and that kind of thing, and all very IRONICALLY. Whereas this seemed sincerely weird. In the original Argentine edition, How I Became a Nun was published as a two-novella volume with The Seamstress and the Wind. I read it on the plane on the way to Argentina and thought it was great. A lot of the book is set in Patagonia, which is huge and flat and empty with extremely high (titular) winds. Several characters on different missions are searching for each other. There’s a propulsiveness to the plot that I think comes partly from the fact that Aira isn’t really worried about continuity, like when kids go, “Okay, let’s pretend we’re in a cave, and you’re a bear, and I have a rock, no wait it’s a magic rock, and actually you’re a wizard pretending to be a bear, and I’m a wizard too, we’re two wizards in a cave…” Which is not to say that it’s chaotic or nonsensical, just that there’s a bubbly inventiveness that keeps things moving.

We arranged to meet in a café. We sat there for about an hour and he never made eye contact with me. I remember at one point he was rolling a straw wrapper up into a little tube on the table, very slowly, not talking, and I thought, “Jesus, please kill me.”

How did having access to Aira work? What was the process of translation like?

I wrote him a letter in care of New Directions, asking if I could translate his book and if he would meet with me if I got this grant I was applying for, and he graciously agreed. When I got to Buenos Aires I called him — I remember I had to ask the desk clerk at the hotel for help, as I had been in Argentina for about two seconds and couldn’t figure out how to work the pay phone in the lobby. We arranged to meet in a café. We sat there for about an hour and he never made eye contact with me. I remember at one point he was rolling a straw wrapper up into a little tube on the table, very slowly, not talking, and I thought, “Jesus, please kill me.” I asked him if I could translate The Seamstress and the Wind or if he thought another one would be be more appropriate, and he said, “People are not good judges of their own work.” So I took that for a go-ahead.

The grant was a teaching assistantship with a project component, and I’d been assigned to a teachers’ training college in Santa Fe, a small city in a very flat, agricultural, flood-prone province. It was about six hours on a bus from Buenos Aires, and I had coffee with him two more times and emailed him drafts to look at as I finished them. He warmed up over time and was really charming. The last time I saw him I came prepared with a list of the knottiest problems in the book, the ones I had been trying to solve for months, and he went over them and explained them, except for one. I showed him a sentence from the third or fourth chapter of the book and said, “What does this mean?” And he looked at it for a minute and said, “I have no idea.”

He read the final draft and approved it, and said I could talk to Barbara Epler, his editor at New Directions. He was really nice to work with, though his reticence is well documented. Rivka Galchen has an awesome essay about spending a few days with him in the June Harper’s.

What did you find most challenging about the project as a whole?

I think, on the whole, the hardest thing might be what’s hard about any creative project — the worry that you’re putting all this work into something that’s never going to matter to anybody else. Literary translation in particular, at least in the U.S., is a teeny little niche. There are only a few publishers that are really open to it. Also, puns. And curse words! It’s so hard to find an equivalent that’s not either too weak or too strong. Which brings up a lot of childhood anxiety about sounding unconvincing with your swears.

A tiny niche, definitely, but Aira is relatively high-profile — he’s been reviewed in the Times, all his books are “blurbed” by Bolaño. Did you feel any special pressure translating him, being new to it?

When I proposed the project in 2006, his profile was a bit lower. But yeah, overall it did feel like a pretty presumptuous move to embark on a translating project with no credentials whatsoever. Most literary translators are academics. I owe a lot of gratitude there to my college adviser for thinking it was a perfectly reasonable idea.

What should be the next novel of his to be translated?

Well, the one I’m most excited to read now is already being translated and will be out next year with New Directions, Varamo, with Katherine Silver. It’s about a Panamanian bureaucrat who writes one great poem. I’d like to do some of Aira’s short stories, like “Mil Gotas,” where the main character is the drops of paint that make up the “Mona Lisa.”

Any other Spanish-language writers you’re hoping to translate?

Two great Argentine writers I’ve been reading lately are Pola Oloixarac and Lucía Puenzo. Oloixarac has a debut novel out called Las Teorías Salvajes that got a lot of attention in Argentina, and Puenzo is a filmmaker — she directed XXY a few years ago, and she’s written four or five novels, only one of which has been translated. I’d love to work with either of them.

Alicia Kennedy is a copy editor, yogi and amateur baker. She is maybe not as boring as that makes her sound.

Yogadoody Suspect Speaks Out

“I was at the yoga festival, doing a little bit of yoga, and I’m just seeing all these goddesses. It seems crazy, but I just felt like I was being blessed by their energy, even though it was unintentional.”

— Boulder yogadoody suspect Luke Chrisco explains the emotions that compel one to deliberately immerse oneself in a portable toilet full of doody at a Boulder yoga retreat. Now you know.

Human Forms, Repent! Stop Killing Wolves And Leave Those Caribou Alone

“By looking at hormone levels in caribou scat, the scientists found that when humans were most active in an area, caribou nutrition was poorest and psychological stress highest. When oil crews left, the animals relaxed and nutrition improved.”

— The caribou herd in the petroleum rich oil sands to the east of the Alberta’s Athabasca River (which is my new favorite name for a river in the whole world) hasn’t been doing too well lately. The Canadian government has started culling wolves in the area to help. But this is wrong, says science. Culling wolves will only exacerbate the problem. Unsurprisingly, the better solution would be culling humans. Or, at least, keeping them away from the caribou.

Get A Load Of The Frederick Law Olmsteds On Her!

“All in all, it was a pretty positive, if somewhat anticlimactic, experience. I tried to act as normal as possible, but it’s hard not to smile when you’re doing something so obviously goofy. I don’t think it’s yet possible for a woman to walk around topless without having people assume she’s pulling some sort of stunt, which is a shame. Granted, I was doing a social experiment of sorts, but it would be nice to be able to do it just because it feels good.”

— Jamie Peck of The Gloss takes a topless stroll through Central Park. WARNING: Includes boobs.

Fun With Maps: Seven Peculiar U.S. Borders

Fun With Maps: Seven Peculiar U.S. Borders

Is Colorado a perfect rectangle? The borders are defined by strict latitude and longitude lines, so by all accounts it should be; but thanks to a surveyor error back in 1879, it isn’t. The kink in the western side of America’s Otherwise Squariest Landmass is just one example of the kind of cartographic aberrations that have made for oddball borders in today’s United States.

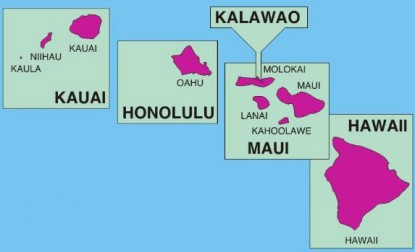

Kalawao, HI

Hawaii is composed of five counties: four counties of comparable size and one 13-square-mile blip, Kalawao County. This small size is because Kalawao County (on the island of Molokaʻi) governs the Kalaupapa Leprosy Settlement and National Historical Park and nothing else. The two even share the same borders. Founded in 1865 by King Kamehameha V and his legislative assembly, Kalaupapa was a forced settlement camp for sufferers of Hansen’s Disease, a.k.a. leprosy. The site was chosen for its incredibly fertile volcanic ash-based soil — it was believed this soil would make it possible for residents to sustain themselves by farming. Which was just as well as the other reason the site was chosen is because it’s completely cut off from the rest of the island by a 2,000-foot cliff.

Kalawao County was created in 1905. Most of its administrative tasks are handled by Maui County, and Kalawao’s sole local official is a sheriff chosen from among the resident population by the state health department. Though the quarantine ended when leprosy was cured in the ’60s, people must still have state permission to visit and no one under the age of 16 is allowed unless they’re a relative of one of the hundred(-ish) elderly leprosy survivors that reside in the county. When the leprosy survivors all die off, it’s expected that Kalawao will be formally annexed by Maui County. (Picture via wikipedia)

Kentucky Bend

The Kentucky Bend is an area of Kentucky that sits completely within Missouri and Tennessee, disconnected from the rest of its own state. To understand how this came to be, we have to look at the entire southern border of Kentucky. Kentucky was once part of Virginia and, in the process of becoming a territory, kept the same southern borders (at 36°30’ N, halfway between the entrance of the Chesapeake Bay and the Albemarle Sound in North Carolina). A few years later, Tennessee separated from North Carolina and, like siblings arguing over the middle seat in a family car trip, each territory accused the other of taking its land.

Thomas Walker, surveyor, set the uneven border between the western edge of Virginia to the Tennessee River as it exists today. The area past the Tennessee River, purchased from the Chicksaw tribe at a later date, stretches to the Mississippi border and sets the border back at the original line, 36°30’ N. West of the Mississippi, it’s Missouri. However, there is a tiny thumb of land both east of the Mississippi and north of 36°30’ — the Kentucky Bend. The fifteen Kentuckians who live there send their children to schools in nearby Tiptonville, Tennessee.

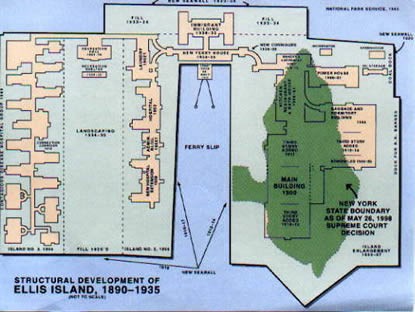

Ellis Island

Ellis Island is partially in New York and partially in New Jersey. Both Ellis and Liberty Islands in New York Bay are technically on the Jersey side of the border, but as they were under NY control before the river was divided, they remained part of NY. But that only applies to what is above ground; the water is in Jersey’s jurisdiction.

When Ellis Island was artificially enlarged in the early 1900s through land reclamation (that is, blocking off an area of water, draining it and filling it with earth; the same process used to create the land used for Wellington, New Zealand’s harborfront and about a fifth of The Netherlands), New Jersey had a legitimate claim: the reclamation project enlarged Ellis Island by 90% and New Jersey argued that the land reclaimed from the bay was theirs. New York got away with the enlarged island until 1998, when New Jersey’s lawsuit against the state of New York reached the Supreme Court. In a 6–3 decision, the Court ruled that while the naturally occurring island belongs to New York, all of the manmade land belongs to New Jersey. Essentially, New York earns tax revenue from souvenirs sold in the museum and New Jersey collects payments from the utilities it provides to the New York section.

PA-20

Elected to the House in 1994, Army veteran Frank Mascara served as representative of Pennsylvania’s 20th district, located in the southwesternmost corner of the state. Following the 2000 Census, GOP-led redistricting eliminated the 20th and redrew Mascara into fellow Democrat John Murtha’s district, PA-12. The borders were so cleverly gerrymandered that Mascara’s house in Monessen ended up in Murtha’s district 12, but his parking spot was in district 18. Had his house been drawn in 18, Mascara would have been up against a relatively weak incumbent Republican. Instead, forced to campaign against a popular Democrat incumbent, Mascara lost by a wide margin.

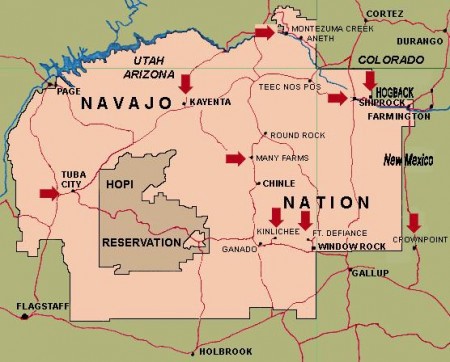

Arizona

The state of Arizona does not observe Daylight Savings Time. The Navajo Nation in Arizona does observe Daylight Savings Time. The Hopi Nation, an enclave within Navajo land, does not observe Daylight Savings Time.

Rio Rico, Mexico

The Texas-Mexico border has been set as the Rio Grande since 1845. So when an irrigation company illegally altered the river’s course in 1906, a tiny section of Texas was separated from the rest of the state. Though technically US territory, Mexico absorbed the area as a sort of resort town, a US territory without enforcement. The area was officially annexed by Mexico as the Horcon Tract under the Boundary Treaty of 1970, a provision of which granted US citizenship to anyone born on the 400 acres after 1906.

Colorado

Colorado certainly looks like a rectangle. The official borders all correspond to latitude and longitude. On the northern side, the border is shorter than the southern one because circles of latitude get shorter as they get farther from the equator and closer to the poles. The state is seven degrees of latitude from east to west and four degrees of longitude from north to south, so the northern border is about 34 km shorter. But there’s a kink in the western border with Utah. Once Colorado was granted statehood, a team of surveyors traveled northwards from 37°N to 41°N, leaving mile markers as they went, as was customary. Deep in rough terrain they slipped a tiny bit west. Though Congress specified 109°03’W as the edge, the official borders are not what is legislated on paper but what is actually marked on the ground. So an error remains along the western border of Colorado, a confirmed non-rectangle.

Victoria Johnson is a cartographer and this is her Tumblr.

Image sources, from top: Maps of United States and Kalawao via Wikipedia; Kentucky Bend image from Google Maps; Ellis Island via NPS.gov; PA-20 via the National Atlas; Rio Rico and lower Colorado map detail both from Google Maps.

Tom Petty Tells Michele Bachmann To Quit Jammin' Him

Here is a song you won’t be hearing at any more Michele Bachmann campaign events.

NYC's 'Saved' Libraries Experience Deja Vu

NYC’s ‘Saved’ Libraries Experience Deja Vu

by Olivia LaVecchia

Just after that one significant law passed on Friday night, Mayor Bloomberg and City Council Speaker Christine C. Quinn met up downtown to make another important announcement: A balanced, on-time budget for Fiscal Year 2012. Details of that budget are still emerging, but the official press release boasts, “We saved … libraries.” But “saved” is relative. While no sources are sure of actual numbers yet, the agreement should prevent branch closures and lay-offs, though service is still likely to drop from six to five days.

Make no mistake, this was a much better outcome than many library supporters were expecting. But this year’s wrangling also represents the continuation of a debilitating cycle that leaves libraries in the lurch every year, stuck counting on budget negotiations to provide not just cash for flex spending, but a basic operational baseline. Which means that, when the city’s scrounging for pennies wherever it can find them, those operational costs turn dangerously subjective: Between 2009 and 2011, the four libraries that comprise the NYC system — Research, New York, Brooklyn and Queens — saw their budgets slashed 40 percent; this year’s cuts chip further. “It’s an ongoing problem,” says City Council Member Gail Brewer, an ardent library supporter. “Every year, the mayor cuts the libraries, and we always try to restore it. It’s part of the budget dance.”

According to Christian Zabriskie, “This year the budget dance wasn’t a waltz, it was a mosh pit.” Zabriskie, a Queens librarian as well as the founder of the advocacy organization Urban Librarians Unite, describes the funding wars as “taking up an enormous amount of energy and an enormous amount of capacity that we could be focusing on helping our public.”

The 2012 budget battle started shaping up back in January, when Bloomberg announced a preliminary budget proposal with cuts that Zabriskie calls “draconian”: $88.4 million — a 28.6 percent reduction from FY ’11 across the public library systems, which losses would have resulted in an estimated 40 branches closed, 1,000 positions laid off, and serious reductions in operating hours. But the numbers were scary not just because they were so deep, but because they were so familiar: The preliminary FY ’11 budget had contained similarly drastic decreases. Supporters had protested, and at the last minute, the City Council had swooped in and saved the day, restoring much of the libraries’ funding. Now, just months after that victory, recently won funds were again on the chopping block. As Linda Johnson, the interim executive director of the Brooklyn Public Library, noted in a May 23 budget hearing, “I am particularly frustrated that $17 million, or two-thirds of [this] cut, is the funding BPL fought for and the Council and Mayor restored just 11 months ago.” (The two-thirds Johnson’s referring to is of the BPL’s portion of the cuts specifically, which weighed in at $24.1 million — budget numbers get confusing fast).

And this time around, it was harder to rally the troops. Though the past few years of budget back-and-forth have given library systems and their advocacy groups an arsenal of fighting tactics, stalwarts like the 24-hour “Read-In” and the postcard-writing campaign attracted less attention (though the latter still received nearly 140,000 submissions). “Everyone knows the budget stinks and everyone’s tired of hearing about the budget,” Zabriskie says. “What last year was seen as a really fascinating, wild thing, this year just did not seem to be sparking anywhere near the same amount of interest.” To combat the jadedness, organizers tried to come up with new, more aggressive strategies, like the mass “hug” of the NYPL’s Schwarzman Building, and a VYou campaign in which supporters recorded videos explaining their library’s importance to them. By the time the cycle swings around next year, activists will probably have to set up French-A-Librarian booths to get any attention.

The idea behind such public displays of affection was to lend faces to library usage and circulation numbers which, against the odds, are on the upswing. At the BPL, 2010 marked a record number of users, and circulation reached almost 20 million items, “[t]he highest level in BPL’s history and a 13 percent increase over FY ‘09,” according to Johnson’s testimony at a March 24 preliminary budget hearing. Part of the reason the libraries have been able to keep on is that, as any recent visitor knows, they’re offering a lot more than books these days: Essential literacy, tutoring and job-training programming have taken on central, and valued, positions. (Not to mention cutting-edge digital projects). In her March testimony, Johnson defined three of the BPL’s primary focus areas as service to immigrants, service to teens, and access to technology.

This demographic may be another reason library funding is such an easy target for budget cuts. Because the people in City Hall aren’t the ones who need many of the services the library provides, there’s a disconnect between the perception of the library’s usefulness and its actual impact. In a June 6 budget hearing episode that’s been oft-repeated among library advocates, City Budget Director Mark Page said that libraries are losing relevance in the digital age. But to Zabriskie, Page can’t pass judgment: “For a man who makes over $200,000 a year, and can buy books and computers, maybe libraries aren’t essential. But for a lot of New Yorkers they are very, very much a big deal.” (An acerbic blog post at savenyclibraries.com drives the point home further).

On April 8, when the City Council responded to the Mayor’s FY ’12 preliminary budget, it proposed a solution to these past few years of budget woes: To create a baseline off of which future proceedings could work, instead of leaving the libraries in limbo from year-to-year with no funds guarantee. “It is time for the City to create an operations policy for the three public library systems,” the report proclaims, “setting standardized minimum levels of service in each borough and providing adequate baseline funding to meet this mandate. Currently, there is no operations policy guaranteeing a minimum service level so that all boroughs have adequate and equal access to library services.”

This is a very good idea. As Zabriskie says, “It would be a huge, huge, huge step forward in stabilizing libraries and library funding.” But it’s likely too big a step for the current budget climate; instead more of an anchor on the opposite end of the spectrum from Bloomberg’s proposed FY ’12 cuts. For now, the libraries have scraped by for another year. But come January, when the Mayor’s staring down an estimated $5 billion deficit, maybe instead of proposing familiarly steep cuts to the libraries he’ll prioritize breaking the cycle.

Olivia LaVecchia is an Awl summer reporter.

Photo courtesy of savenyclibraries, used with permission.

You Don't Have To Be Crazy To Live Here, But You Will

Living in large cities makes you stressed out and crazy, but I’m pretty sure that still beats BEING BORED AND HAVING NOTHING TO DO. [Via]

Bear Jams!

Those are some jamming bears! “An infamous family of grizzly bears is creating quite the uproar in Grand Teton National Park this summer. Known by their identification numbers, No. 399 and her daughter, No. 610, have five cuddly-looking cubs between the two of them. The bunch has been creating an unprecedented number of “bear jams” — where shutter-snapping tourists crowd around to take photos of the camera-friendly grizzlies. Park rangers have had to intervene to keep tourists at a safe distance.” More bear jammery below!

The Shocking True Tale Of The Mad Genius Who Invented Sea-Monkeys

by Evan Hughes

“Sea-Monkeys, do monkeys / Story of my life / Send three bucks to a comic book / Get a house, car and wife” — Liz Phair, “Gunshy”

In a 2002 interview with Erik Lobo of Planet X magazine, Harold von Braunhut comes across as the kind of charming old guy who might detain you in conversation a bit too long if you were volunteering at a home for the aged. An inventor and entrepreneur who brought us legions of wonderfully gimmicky toys before he died, at 77, in 2003, von Braunhut holds forth about times gone by, interrupted only when his cockatoo chews at the wire connecting his hearing aid to the telephone.

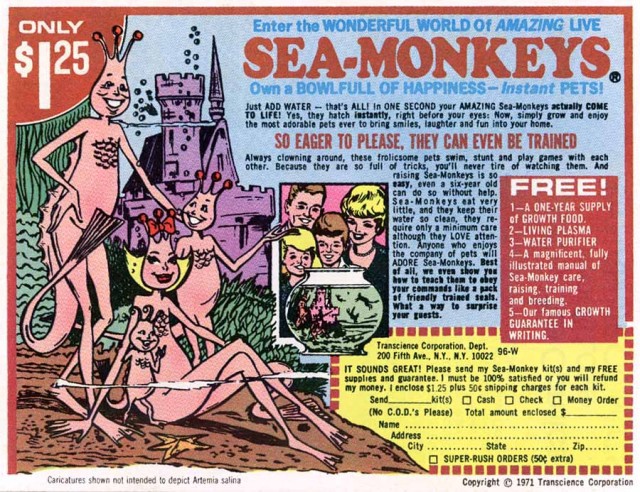

Von Braunhut was a short, balding man who had the accent that turns “beautiful” into “bee-YOO-dee-full,” and he often cast himself as the guy they all doubted until he showed ’em. In the interview he seems to delight in telling Lobo about his most famous and successful novelty item, Sea-Monkeys. These little critters, you may recall, carry with them the promise of “a BOWLFULL OF HAPPINESS — Instant PETS!” They’re supposed to arrive in the mail, spring to life in water, and soon start horsing around and making babies. According to von Braunhut, the problem with selling Sea-Monkeys early on, ya see, was that “nobody believed it!” He adds, “It’s a little bit like the story of the Wright brothers.”

The accounts Von Braunhut gave of his adventures in American kitsch are consistently winning. Granted, he makes some claims that a skeptic is inclined to independently confirm. At some point in the years after he raced motorcycles as The Green Hornet, von Braunhut worked as a talent agent of sorts. He tells Planet X about a stunt performer he used to manage — the article has von Braunhut calling him “a fella by the name of Henry Lamore” — who would dive from a height of 40 feet into a kiddie pool filled with 12 inches of water. I began to lose faith while trying to verify this doozy, but it turns out that the Internet allows you to watch a man named Henri LaMothe still pulling off this feat at 71 years old, as an opening act for Evel Knievel.

As anyone sold by the Sea-Monkey ads could tell you, it was hard to say exactly where von Braunhut was walking on the terrain between truth, embellishment and con. That was his gift. He convinced us to look at the jazz hands and lose sight of the footwork. Von Braunhut’s inventions were not quite what they seemed to be. Neither was he.

***

If you so much as flipped through a single comic book sometime after 1962, von Braunhut’s ads might have gotten you curious about whether his doodads worked even approximately as advertised. For Sea-Monkeys, the ads portrayed a cheerful family of humanoid creatures bearing crowns of some sort and hanging out by their underwater castle. Mom had blond hair. The fine print said something about “caricatures,” but never mind — the bigger type spun a magical tale of pets that would be “like a pack of friendly trained seals” if you followed the directions. Von Braunhut wrote the copy himself, for at least the first couple decades.

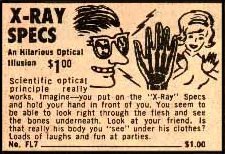

Ads for another von Braunhut invention, the X-Ray Specs (not to be confused with the English punk band X-Ray Spex), promised the power to see through obstacles and showed a guy grinning at a woman in a dress. Again there were words like “illusion” — the effect is created by feathers or grooves in the lenses, von Braunhut’s patents show — but that wasn’t where the average comic book reader focused his attention. In von Braunhut’s most impressive marketing coup, he peddled “Invisible Goldfish.” The kit included a glass bowl, a handbook and fish food. That was it. He said they sold out. There was a 100 percent guarantee that the buyer would never see the fish, and I’m 100 percent sure that guarantee never failed. The greatest trick the Invisible Goldfish ever pulled was convincing the world they existed.

How did we fall for von Braunhut’s copy, even as children? It’s hard to remember a prior state of innocence once you’ve come to understand what salesmanship is. When it came to X-Ray Specs, if you were savvy enough to be suspicious, you were also savvy enough to understand that there were naughty secrets your parents didn’t want you to know — maybe this was one of them? Hey, maybe it was worth a buck to find out.

In a lot of cases, von Braunhut’s claims were sort of true. Sea-Monkeys are a variant of brine shrimp, which are harvested for use as fish food and begin their life as cysts that can last for years in a kind of suspended animation if kept in dry conditions. Von Braunhut’s creatures come in packets, looking like white powder. With proper care, Sea-Monkeys can grow to be visible and pretty neat, even if they bear no resemblance to the illustration. Watch them dancing around to Chopin.

Von Braunhut said that he brought us Sea-Monkeys because of his love of the natural world and the animal kingdom. The Safeway near von Braunhut’s home in Bryans Road, Maryland, would set aside expired bread for von Braunhut and his wife, Yolanda, a considerably younger, chatty brunette, as one former store employee I contacted remembers. The couple would sometimes buy two or three cartloads of the bread at a time. They were feeding animals at their 70-acre property, which they called the Montrose Wildlife Conservation.

Legions of children enchanted by Sea-Monkey lore have seen disappointed to see their smelly little specks die in a matter of days; but others have made obsessive websites and written books about their ongoing Sea-Monkey love. Sea-Monkey eggs went to space with John Glenn in 1998 and came back still good to go. The creatures inspired a (bizarre) short-lived live-action series for kids on CBS in the early ’90s, and they were featured on “South Park” and in a Pixies song. Michael Birnbaum’s Empire Pictures bought the film rights to Sea-Monkeys in 2006 to develop an animated movie.

Von Braunhut was a wellspring of ideas, and some of his novelties relied less on inflated ad copy. He invented those dolls’ eyes that close on their own when the doll is laid down on its back. And he was the man behind the game Balderdash, which tests your ability to call baloney. (I won’t linger on the irony.) If you grew up in America and even dabbled with toys and games, going through the 195 patents that von Braunhut held is bound to bring a smile.

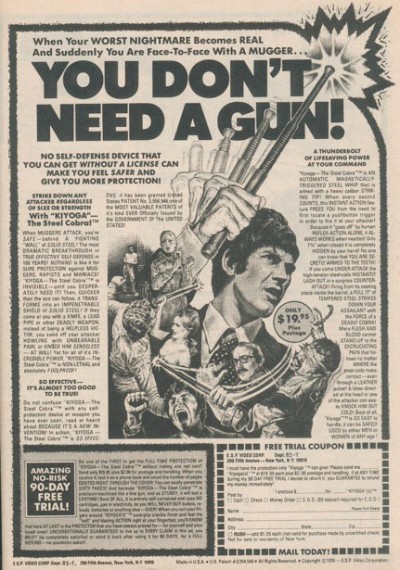

Until you see this one: “Spring whip defensive mechanism having means to permit disassembly thereof.” Don’t pull on this thread unless you want things to unravel.

***

The “spring whip defense mechanism” was brought to market as the Kiyoga Agent M5, a spring-loaded rigid whip that telescopes out of its handle with the press of a button. When von Braunhut was passing through security at LaGuardia Airport in 1979, his attaché case carrying six of these devices attracted attention, and he was arrested on illegal-weapons charges. He won a dismissal on the grounds that the Kiyoga Agent M5 was not a “bludgeon” and did not meet the criteria of any banned weapon. But the device was advertised as the answer “if you need a gun but can’t get a license,” because “its hornet’s nest of piano wire steel springs inflict excruciating agony on your assailant.” A courtroom demonstration showed that its effectiveness didn’t quite live up to the billing, which is hard to believe, I know.

But where was it advertised? One venue was the newsletter of the Aryan Nations, the anti-Semitic, white supremacist group. Its founder and then leader was Richard Girnt Butler, whom the Southern Poverty Law Center called “the hub of the wheel of racist revolution … the elder statesman of American hate.”

When Butler was under indictment for sedition in 1987 for allegedly plotting to overthrow the U.S. government, he sent out a fundraising appeal. It included a brochure for the Kiyoga Agent M5 and stated that the “manufacturer has made a pledge of $25 to my defense fund for each one sold to Aryan Nations supporters.” (Butler and his codefendants were later acquitted by an Arkansas jury.) Speaking to the Spokane Spokesmen-Review in 1988, Butler described Harold von Braunhut as a longtime friend “who has supported us quite a few years.” And in fact Braunhut appeared frequently at the yearly Aryan World Congress at Butler’s “whites only” compound in Hayden Lake, Idaho, sometimes as the lighter of the burning cross, according to the Los Angeles Times.

An Assistant U.S. Attorney, Thomas M. Bauer, told the Washington Post that in a 1985 weapons case against a member of the Ku Klux Klan, Grand Dragon Dale R. Reusch, von Braunhut was prepared to testify that he had lent Reusch about $12,000 so he could buy 83 firearms. Bauer told the reporter that von Braunhut was “very pleasant and cooperative” and “brought some of his little toys along,” including Sea-Monkeys.

The general Aryan Nations view holds that Jewish people are directly descended from the devil. It seems clear that von Braunhut, who owned Nazi memorabilia and once said Hitler “just got bad press,” signed on to these beliefs. But one has to wonder what brought him to the point of nodding along when his friend Butler, for instance, described Jews as “the bacillus of the decomposition of our society.” Aryan Nations members might have been dismayed to hear that von Braunhut engaged a law firm called Friedman and Goodman early in his career. They might also have been puzzled that his name was listed on early patents as Harold N. Braunhut. The middle initial stands for Nathan. Harold von Braunhut was born and raised Jewish.

***

It’s not entirely clear why the Aryan Nations didn’t cast von Braunhut out after the Washington Post gave a thorough account of his Jewish origins in 1988. Von Braunhut said, “I will not make any statements whatsoever” on the topic when questioned for the article, then stopped returning calls. The article also reported that he was born in Manhattan and that he gave an address in (heavily Jewish) Brighton Beach, Brooklyn, when he briefly attended Columbia University. He lived in New York City into the mid-’80s. The Post reported that a Harold Braunhut paid for the upkeep of his parents’ graves at a Jewish cemetery in Long Island in 1979. Which is hard to square with the fact that von Braunhut was helping a Klansman buy 83 guns in 1980 at the latest.

Perhaps the Aryan Nations allowed von Braunhut to stay in the fold because Butler liked having a wealthy backer, as Floyd Cochran, a former spokesman of the group who later renounced it, has said. Von Braunhut made a lot of money from all those whimsical inventions that kept America laughing.

It also seems plausible that the Aryan Nations is the kind of organization that believes the Washington Post needs to stop telling lies and get the hell off my lawn. If there’s a massive conspiracy to bury the truth and subjugate white people, the Washington Post is definitely part of it.

Members of the Aryan Nations wanted to believe what they wanted to believe. For these hateful people, von Braunhut said all the right things, made the right contributions and got the same hard time from the media that they did. As for the, uh, rumors about his past, the Aryan Nations founder himself seemed to be looking the other way. “Sea-Monkeys, do monkeys / Story of my life.”

It’s tempting to think that von Braunhut’s biggest con was convincing himself to buy into preposterous and despicable ideas. Unfortunately for the world, however, that’s not so unusual. More extraordinary is this: Richard Girnt Butler, who preached that Jews were descended from Satan, had a man who was known to be born Jewish preside over his wife’s funeral in 1995. Harold von Braunhut had won Butler over. That’s what salesmen do.

Von Braunhut had the knack for making facts go away. Look at the hands, lose sight of the feet. The man made a lot of us believe that we could see through clothes, that smiling underwater pets would arrive in the mailbox. He made us believe in invisible goldfish.

Evan Hughes’s book, Literary Brooklyn, a work of literary biography and urban history, will be published in August by Henry Holt. He’s on twitter.

Photo of actual sea monkey by you get the picture, used with permission.