Flume, "Tiny Cities" feat. Beck (Lindstrøm & Prins Thomas Remix)

That was the easy part.

Well, you did it. You made it to Friday. Yes, it was a short week, and nobody expected too much out of you, but an accomplishment is an accomplishment and I want to congratulate you. You knocked that first week down. Now you just have to do it 51 more times, at full speed, to finish out the year. Of course for most of it Donald Trump will be president and terrible things will be happening to your country and world. Plus there is still so much winter to get through. So much winter. But right now it’s Friday and you survived. Concentrate on that. The bad stuff will wait for you. It’s nothing if not patient, the bad stuff.

Anyway, some days I am of the opinion that the greatest cultural achievement of this rapidly aging decade happens to be the Lindstrøm & Prins Thomas remix of Haim’s “Forever,” which means I might be more receptive than most to that duo’s reconstruction of the Flume/Beck track “Tiny Cities.” But oh my God, it’s so good. As terrible as everything else is, that’s how great this is. For the ten minutes it’s playing you can almost convince yourself things may be okay, or at least stop thinking about how awful they actually are. It’s not going to change your life, this track, but it will distract you from what your life is, and in these troubled times that is almost as good. Enjoy.

New York City, January 4, 2017

★★★ Lines of dampness traced the paving joints of the roofdecks, and a once-impressive umbrella lay in ruins by the curb, but the breeze was dry and the sun was working on shining over the schoolyard. The clouds came back to quash the later morning, then finally relented. Clear, pure light took over till the last few tiny clouds turned delicate pink. The wind at twilight was not cold but it was strong enough to squeeze a tear from an eye and send it crawling sideways along the cheekbone. A dropped cigarette rolled away in a trail of sparks before the smoker caught it and stomped it out. Clear plastic bags rattled over the discarded Christmas trees walling off the street.

It's Fraud All The Way Down

Everything is a scam if you look closely enough.

If tales of monetary skulduggery are your thing, please do enjoy this piece about the Platinum Partners hedge fund, “alleged to be one of the biggest investment frauds since Bernie Madoff’s.” There is way too much in here to pull out, but this will give you a taste:

[In 2010] the fund popped up on the radar of the SEC, which was investigating a scheme involving a Los Angeles rabbi who, the agency later alleged, tricked terminally ill hospice patients into providing personal information so annuities could be purchased in their names. The annuities were funded by Platinum, which had put up more than $56 million, according to investigation records. It spent four years building its case. But when its enforcement actions were announced in 2014, the SEC only fined the intermediaries who ran the scheme and a shell company set up by Platinum to hold its money.

There is a lot to appreciate here, so long as you don’t allow yourself to think about how almost every financial organization or instrument is a scam in one way or another and everyone is trying to cash out before they get caught. Anyway, have a look.

A Poem By Monica Ferrell

A Funfair in Hell

after Van Gogh’s “Le café de nuit”

While the proprietor looms at the center of the bar

in white linen suit, as though on safari,

I trace the grooves worn in this old wood,

I taste my beer and it is cold as some god.

The lights in hell must be something like these,

immortal as remorse, as words once they are spoken,

and the people in hell must be like these men

holding engines of heads spinning emptily in their hands.

The proprietor wears a flickering smile

pretty as the word syphilis.

He shines one beer tap, then another.

The silence in my mouth is a piece of felt.

I am ready for my annunciation, Angels.

I am ready for the enormity.

Bring out the unguents, the strigil and gauze.

Weigh my heart against a feather.

Monica Ferrell’s second collection, Oh You Absolute Darling, is forthcoming from Four Way in 2018. She is the author of the novel The Answer Is Always Yes and of Beasts for the Chase, a finalist for the Asian American Writers’ Workshop Prize in Poetry.

The Poetry Section is edited by Mark Bibbins.

Kanye West Album Rankings Are Like Astrological Signs

Except real.

Complex magazine made waves Wednesday by publishing their definitive ranking of all of Kanye West’s albums to date. The list includes all 8 of West’s solo LP’s, plus his G.O.O.D. Music collaboration album (which seems less relevant imo but hey run your magazine however you’d like). Anyway, as you can guess, people are getting heated in the comments.

We ranked every single Kanye album. Pray for our mentions. https://t.co/SB35na1s9n

— @Complex

Complex’s ranking is:

9. Cruel Summer

8. Late Registration

7. 808s and Heartbreak

6. The Life of Pablo

5. The College Dropout

4. Yeezus

3. Watch the Throne

2. Graduation

1. My Beautiful Dark Twisted Fantasy

But people on Twitter contain multitudes. Chance the Rapper tweeted his own Kanye list at the magazine after taking issue with the standing of “Late Registration,” and now fans and journalists are following suit using #KanyeRanked. Normally a hashtag game like this would gross me out, but there’s something so nerdy and organic about it that I’m charmed despite myself. It’s like a Stones/Beatles or Floyd/Zeppelin debate in that the stakes are low and there is no right answer, but better because we’re not in a Milwaukee basement in 1979. Debating things’ goodness and badness like this lets people with encyclopedic knowledge of niche topics release their pressure valves and blow off some steam at one another in the name of art, and considering the amount of steam people have to blow off in early 2017, it somehow seems extremely healthy to focus on something you love a lot.

Plus, we learn a lot about a lister by how they rank these records. West’s albums are different from one another, and the fact that I’m seeing things that register as unlistenable for me topping some people’s lists is shocking in a fun way! You’re out there?! Stanning for “808s and Heartbreak”?! “Love Lockdown” did it for you more than “Roses”?! What a rich and complex tapestry our society is!

It’s like we’re all talking about our star signs, only they’re linked to something less arbitrary than a birthday. And that can be a fun lens to look at the world through for five minutes on a Thursday afternoon. Or whenever, really,

American Pastoral

Can a yak economy flourish in cattle country?

Sometimes in or around Athol, a hamlet of just over six hundred people, down the highway from Lake Pend Oreille in the Idaho panhandle, you’ll see a septuagenarian riding a half-ton yak. They are Lynn Taylor and Makloud, the latter of whom, since Taylor started raising him from infancy about a decade ago, has taken to following the old rancher around like a dog. The duo cut such an odd picture, cantering about buddy-buddy through the tinder-dry pines of nearby Farragut State Park, that they’ve become local celebrities — even the Spokesman Review, eastern Washington’s paper of record, saw fit to report on Makloud’s urinary tract issues last summer.

Makloud isn’t famous because he’s a yak, an animal many would think of as totally foreign to America, though. He’s just famous because he’s especially gregarious. Oddly enough, yaks have become an increasingly common sight in Idaho and throughout the American West. So have a number of other exotic species — from alpacas to ostriches — as rural entrepreneurs, hobbyists, and old farmhands cast about for some new niche in the turbulent modern world of American livestock. Yak herds have been slowly but steadily growing in number since the late 1980s thanks largely to their unique suitability to the American landscape and growing appeal within the consumer market. Although they’ll likely never be as popular or common as cattle, yaks are well on their way to becoming an established and highly visual mainstay of the countryside of the Mountain West.

First domesticated around five thousand years ago in the southern Himalayas, yaks have long been beasts of burden as well as sources of deep red meat, thick milk, and soft wool in places like Nepal and Tibet — from whence the word “yak” originates. Some regions, like Gilgit-Baltistan in Pakistan’s cut of the Himalayas, even use yaks as mounts in traditional competitive sports, like polo or yak-back races (which look even cooler than they sound). Living over two decades on average, with males weighing between twelve hundred and fifteen hundred pounds (and females half of that), they offer years of good breeding and service and hundreds of pounds of meat when slaughtered. (Wild yaks, Bos mutus, are even larger, but have a much nastier temperament than the domesticated Bos grunniens, a name that actually means “the grunting ox.”) Throughout the region, farmers lead a combined herd of well over ten million. Until the early twentieth century, though, they were almost entirely absent outside of the Himalayan region.

Yaks first came to America through the efforts of Ernest Thompson Seton, an English immigrant to the U.S. by way of Canada, who co-founded the Boy Scouts of America in 1910. Two years before that career high, the naturalist-survivalist Native-American-distorting-appropriationist Seton somehow got it into his head that yaks would do well on the North American prairie. After years of effort, he arranged for nine Mongolian yaks to make their way to Canada, where they were dumped on some Alberta ranchland for experiments — that never went anywhere.

A broad awareness of yaks and their utility persisted in the US; recognizing its quality, wig makers used yak hair to make fine clown wigs and even the Ur Chewbacca costume in the 1970s. But many didn’t think yaks could be viably ranched in the US, if they thought of them at all.

Then in the late 1980s yaks attracted the attention of those seeking alternative livestock — like Athol’s Taylor, who discovered them while researching ranch options in 1989. Interest grew rapidly enough that in 1992 members of fifteen ranches formed the International Yak Association (IYAK). In 1997, the beasts made an appearance at the National Western Stock Show, basically the Consumer Electronics Show for ranchers. Within a decade, the number of ranches recognized by IYAK had doubled, and as of today there are well over a hundred in the U.S.; national yak herds have increased from just two thousand around 2003 to over ten thousand today. Many herders cluster in Colorado and Montana, but outposts of American yak culture have sprouted up in Vermont, California, and even Texas (though the Dallas-area rancher experimenting with them has had trouble with the heat).

That might not seem like much in the grand scale, but it’s an impressive growth curve when you consider the rapid collapse of the other exotic ranch animals that took off in the late 1980s. During that decade, growing interest in alpacas, emus, guanacos, ostriches, and vicunas, prompted the F.D.A. to offer inspections for the slaughter and management of a wider range of animals than ever before. Spurred on throughout the 1990s by aggressive marketing (including a range of infomercials) projecting the notion that exotic animals were easy to raise and would yield quick and easy money from sales to a public eager for novel meats and animal byproducts, herds grew rapidly. By 1993, there were fifty thousand ostriches and thirty-five hundred ostrich farms in the US; by 2007, there were around a hundred thousand alpacas. They were so common in the rural West especially that every now and then a bemused hiker would happen across a renegade emu or llama on the lam.

The exotic animal bubble was just that; herders never developed viable domestic markets or processing for their meat or byproducts (like alpaca wool or emu grease). Those who profited largely made money by selling breeding stock animals to each other. By the early 2000s the bubble popped, with exotic ranches downsizing or going out of business, sometimes leading to the mass neglect and death of small herds at the hands of incompetent amateur owners.

The only exception was the bison, America’s native bovine species (which shares an ancient common ancestor with yaks). Once numbering up to thirty million on the Great Plains, bison were nearly hunted to extinction in the 19th century. But thanks to private ranching spurred on by the same market impulses that drove other exotics — and bolstered by the public support of conservationists and big names like media mogul Ted Turner — there were over four hundred thousand bison in the U.S. by the early 2000s, mostly in commercial herds whose sizes seem to have stabilized over the last decade. Their meat even made it onto mass supermarket shelves at a fair price.

Lacking the same patriotic narrative and history, yaks have not taken off with equal alacrity. But their steady growth throughout the decline of other foreign exotic animals in the U.S. is remarkable. It’s due in part to the fact that herders have made an honest effort to develop markets for every part of the yak, with only a few breeders devoting most of their time and efforts to selling yaks to other ranchers. Yak fibers, laboriously worked from their coats, are prized by some for their relative affordability and quality and are essential within niche industries like wig-making and fishing-fly manufacture. Yak meat is far less fatty than beef or even most chicken, largely organic, high in healthy oils, and (while more expensive than most beef or even most bison cuts) cheaper than many exotics. Even their bones have found a market amongst artists and decorators and byproducts among select dog-treat makers.

More importantly, yaks fit into underutilized parts of the American landscape (by livestock at least) exceptionally well. Nimble on their feet and adaptable to a range of temperatures, yaks do well on open tracts of scrub mountain land. They’re also ravenous wild foragers, eating almost anything (save milkweed), meaning they can graze over land other animals have used and still do well. Extremely docile, they don’t require heavy fencing (like aggressive bison) — and will at times respond to names like a pet. Capable of fending for themselves and surprisingly disease-resistant, they’re low-maintenance in the extreme. To cap it all off, they require only a fraction of the amount of food cattle require to produce the same amount of incredibly rich and juicy meat.

All of this appeals not just to entrepreneurs looking to make use of often-neglected resources, but to some cattle ranchers as well. Although many ranchers are relatively intransigent, the industry has faced tough times in recent years. Beef prices have plummeted over the past couple of decades, and national herd sizes are largely stagnating as Americans increasingly opt for other sources of protein. Even some bison herders have opted to turn to yaks, especially after recent drought-linked hardships.

There are still quite a few barriers to the growth of the American yak herd. Yaks take twice as long as cattle to mature, and the small size of the market means that right now herders have to pay a premium to clear health inspections. “The beef guys will kill more cows in a single shift in one plant than there are yaks in the whole country,” Jim Watson, the then-head of IYAK, told GOOD Magazine in 2014. Consumers aren’t familiar with the meat, and there is limited information and support for new herders.

But yak herders have long reported that there’s more than enough demand for their products. Every year, more restaurants and retailers are opening up to yak meat, just as awareness of yak byproducts has grown, slowly helping the national herd to grow throughout the mountains with relative security. “It will be even larger,” Watson said, “but still farm-based and local.”

While it will never rival cattle, or even bison, the yak economy is a constantly expanding niche in lands long devoid of serious herding. Small herds of a few dozen to a couple hundred shaggy, gentle beasts will likely continue to crop up along the spine of the Rockies and even, perhaps, parts of the Appalachians, over the coming years, growing more and more visible and normalized. Eventually, they may even become an accepted and everyday symbol of the Mountain West, a landscape into which they slide physically and psychologically with ease, just as cattle in the Open West.

Will Someone Please Tell Me If Ravel's 'Boléro' Is About Sex Or Not?

Classical Music Hour with Fran

Happy new year? Does anyone know if Maurice Ravel’s Boléro is actually about sex? Please let me know. I started this column by going to the Wikipedia page for the Boléro and control+F-ing “sex” and it came up fewer times than I expected it to, so now we have a mystery on our hands.

The Boléro is a piece you’ve almost definitely heard. Premiering in 1928, Ravel’s Boléro is literally just a crescendo of a melody. That’s the whole thing for fifteen minutes. It for sure should not work. On paper, “the same thing over and over again, but louder each time” sounds like a goddamn nightmare. But it’s not! It’s amazing, somehow, and it cemented Ravel’s place in both French and general classical music history.

Ravel lived from 1875–1937, which puts him on the later side of some of the Romantic composers I’ve previously written about, and he’s namely remembered as an Impressionist, not unlike our pal Debussy. Ravel was a fairly gifted pianist — his compositions were often first written for piano, then re-arranged for a full orchestra. But he plateaued at a young age, and then turned to composing. He was also, as it seems from some general research, was kind of a bad boy? Like, at least he wanted to be a bad boy. Around the turn of the century, he started hanging out with a group of other musicians and composers and artists known as Les Apaches which translates, broadly, to The Hooligans. Which, like, calm down. Beyond that, a lot of details about Ravel’s personal life remain a mystery, which, okay, maybe he’s a little bit of a bad boy then.

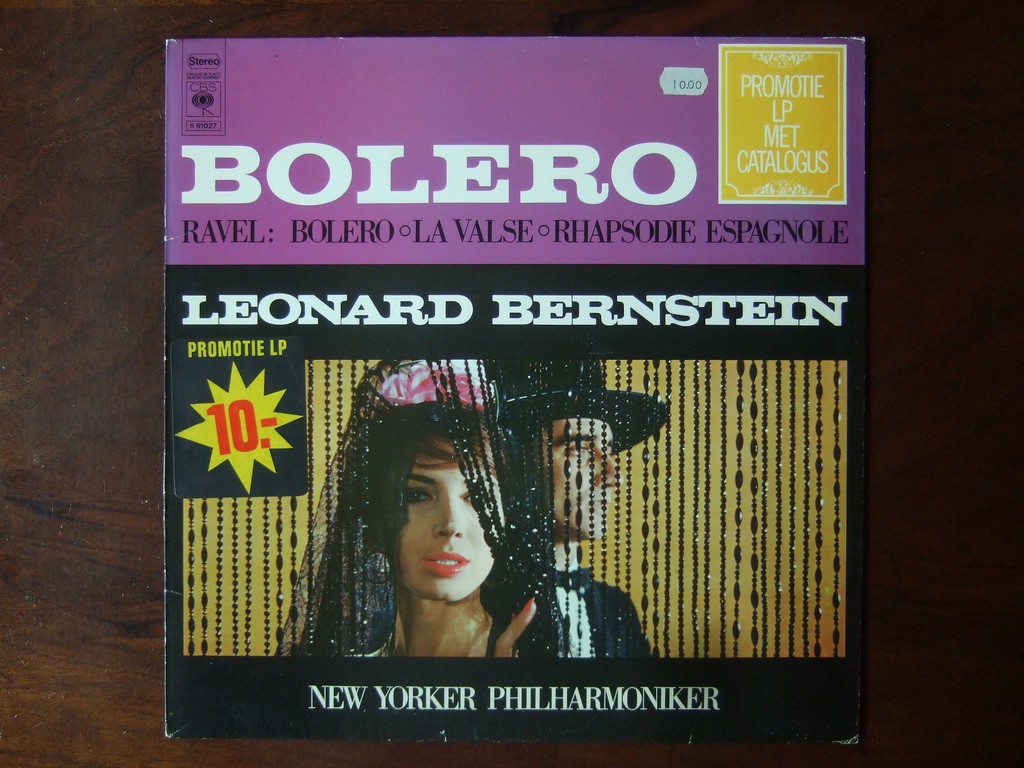

What’s generally cool about Ravel being situated a little later in time than many composers I’ve previously written about is that Ravel lived long enough to see jazz. Remember jazz, from La La Land? I would never say Boléro itself is jazz, but it is jazzier, no doubt, than other pieces I’ve written about before. Initially commissioned as a ballet, Boléro is often just performed on its own, as a standalone piece of music. I prefer this recording of Leonard Bernstein conducting the New York Philharmonic (because I try to link to Bernstein whenever I can; he’s the best).

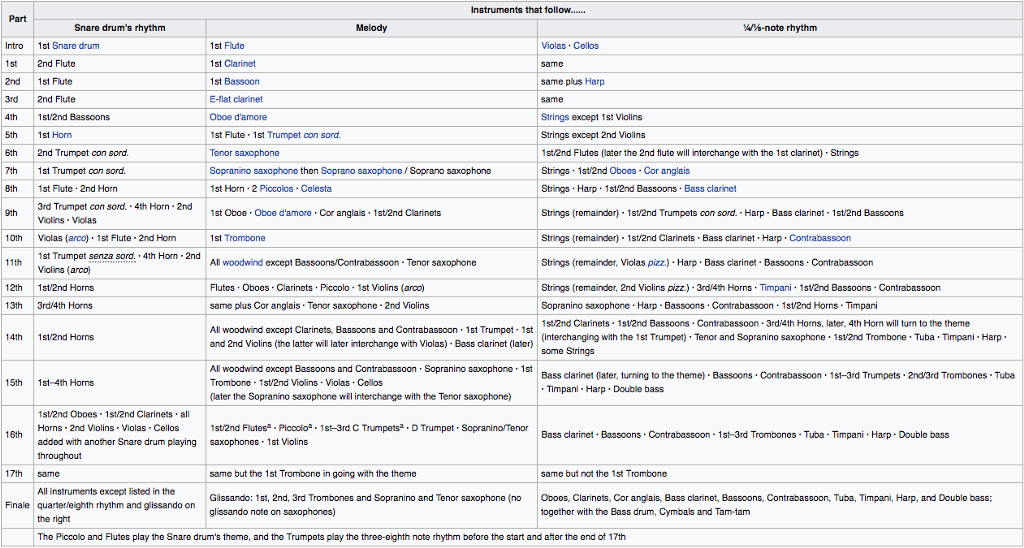

So you’ll listen to the Boléro and you’ll agree: damn, this is really just the same… thing… over and over again… but it also works? I mean, this is Ravel’s most famous piece! This!!! You really can listen to it all the time for a long time, the way I do with other songs that sound the same over and over again (see: my top three Spotify plays from 2016). Some maniacal Wikipedia editor actually assembled this fascinating chart of the order each instrument comes in playing the melody.

Boléro starts with a quiet snare drum playing the essential rhythm of the piece. This continues throughout. The snare is forever. It’s endless. It’s both a dream and a nightmare of a part. I will say I’ve both longed to and never ever wanted to play Boléro as a percussionist. It’s both iconic and torturous (isn’t most good art? Idk). The woodwinds layer themselves in, and as the piece continues, the early instrumental additions wind up playing the same rhythm as the snare.

It’s insane that this is music? But it is! It goes on for a full 15 minutes, so much so that by about the 12-minute mark, as it’s really revving up, as literally every single instrument in the orchestra is all playing the same thing, at least one little part of you is asking how it’s still going. But it’s a perfect crescendo. It’s elegant and mathematical. And it’s catchy. I have to give credit where it’s due: this is a catchy melody you can listen to on repeat, because it’s meant to be listened to that way, because it’s played that way. That’s not to say that Boléro hasn’t pissed some people off. There’s an anecdote from its premiere in which an old woman shouted “Rubbish!” at the end (old women rule), and Ravel responded with some variation of, “this lady gets it.” So he knew he was trolling, more or less, and even he was surprised by the general accolades given to Boléro.

But still: why do I think Boléro is about sex? This can’t just be a made-up thing, and I’m not a pervert either, I promise, truly. Ravel did not set out to write it about sex; it’s really just based on a bolero, a type of Spanish dance that isn’t more or less sexual than most types of dancing. Wikipedia cites some references to it being used in the film 10, which I’ve never seen but uses the word ‘sexy’ in its IMDB description.

So, like:

Did someone come up to me when I was impressionably young and say, “Ravel’s Boléro is directly about sex and this is both historic and true,” to me even though none of this is true?

Is most music actually very sexual? (Do not make me link to the Seeb remix of “I Took A Pill In Ibiza” again.)

Or is anything that kind of repeats itself over and over again basically taking on the form of, well, sex?

This is the kind of thing where, if considered over and over again, will drive you insane, no doubt, so I’ll let it rest for now. It’s not about sex. Although maybe it is, but maybe it isn’t. It’s weird if all of this was just, I don’t know, self-generated, but I can’t ever listen to Boléro without thinking it’s sexy. There’s a coyness to it. It’s playful in this borderline irritating way — maybe because Ravel knew he was just getting away with something when he wrote a piece that was the same thing over and over again. I love that it never really speeds up; it just becomes more. It lilts and bounces, tumbling over and onto itself. It’s gotta be about sex, right????????? Anyway, consider the fact that I’ve possibly cursed you with the same assumption about Boléro, leaving you to wonder as the melody starts over again.

Fran Hoepfner is a writer from Chicago. You can find a corresponding playlist for all of the pieces discussed in this column here.

What's Wrong With This Tweet?

Let’s do a brain-building exercise.

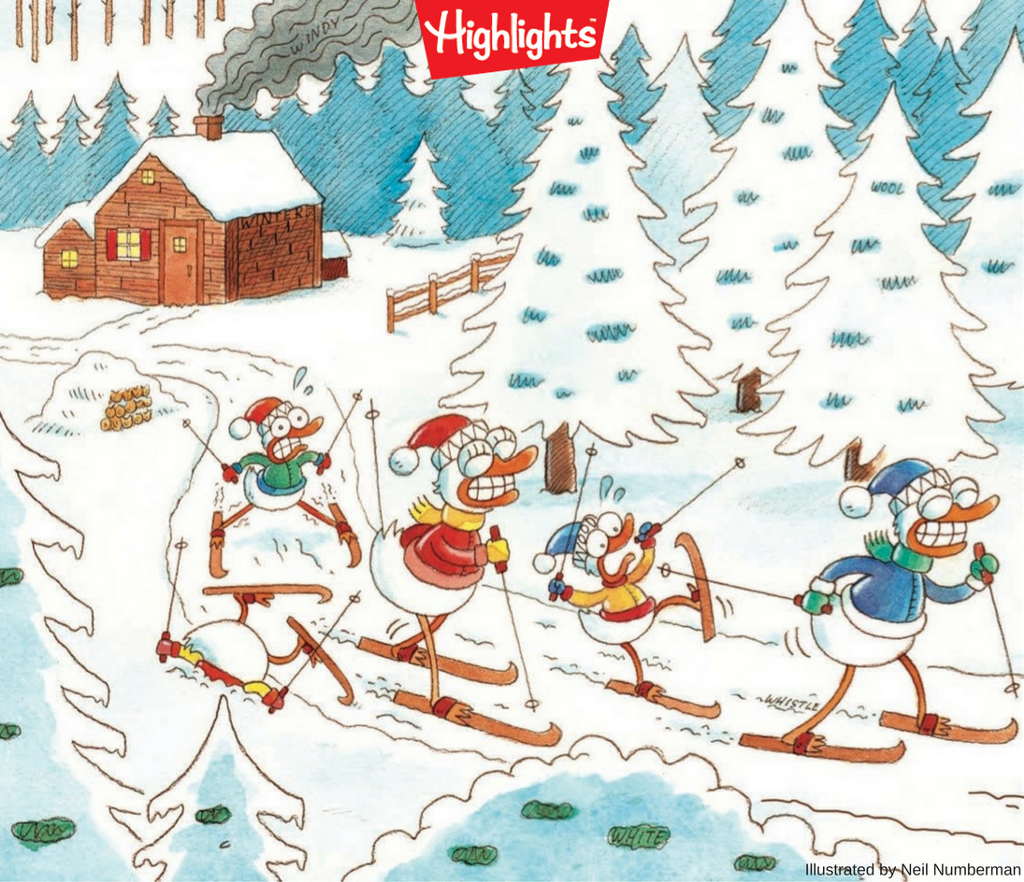

Remember how Highlights magazine would run puzzles where your main objective was to spot what’s off? They’d give you, say, a scene of a beach with the directions, “Spot the five things that are wrong in this picture.” Sometimes it would be obvious (that palm tree has pizza slices instead of leaves!), but other times it would be a little tougher to track down (that lifeguard’s goggles are missing a lens!). Sometimes they’d really stump you with one of the details, and you’d have to wait until they printed the answers in the next issue to figure out what you had missed.

I bring all of this up because the Washington Post’s Express free daily paper did a tweet this morning that is essentially one of those puzzles. Two things are wrong with it, and one of them might be easier to spot than the other:

Can you detect the problems? One is spelling-related, so you might notice it off the bat. But the other is semiotics-related and may take a second or two. Pause to consider the tweet for as long as you’d like, because I’m about to solve the puzzle for you.

Ready?

It’s : 1) “today’a” and, 2) the male gender symbol in an illustration about the women’s march on Washington. One is what happens when you’re about to leave the office and just need to schedule one more tweet really quickly, the other is what happens when you are an illustrator and make a mistake and then none of your editors notice the mistake and it gets printed onto a bunch of newspapers.

The paper has since deleted the original tweet and shared new cover art with the announcement that they are “very embarrassed,” but tbh I am thankful. That was a fun brain exercise. Keep us on our toes, Express.

Lowly, "Prepare The Lake"

We’re all holing up from now on.

Can you feel it? We are entering that chunk of the calendar where we stay indoors in the evening. Outside is out as the comforts of the couch and the grim relentlessness of the dark conspire to keep us from planning anything that requires more than minimal standards of hygiene or sociability. Welcome to the long, sunless season of doing nothing and not particularly minding it. It’s supposed to snow here tonight, if you need your first excuse to kick off staying in. Let’s make plans to catch up in spring.

Here’s something from Awl favorites Lowly, whose debut album Heba is out next month. Be sure to stay in and listen to it. Enjoy.