Pablo Dylan, "Top Of The World"

“I mean, really, my grandfather, I consider him the Jay-Z of his time.”

— Pablo Dylan, 15 years old, rapper. Jay-Z has a new song out today, too. It borrows heavily from Duckie from Pretty In Pink.

Mammoth Silverback Gorilla Bling Identified

Back in January, we posed a question : “Dear Insane Silverback Gorilla Bling, What is your sad story? Why were you sitting in the window of an otherwise unremarkable jewelry shop in New York’s Diamond District, just after Christmas, amidst other comparatively tasteful — if far less garishly ambitious — baubles?” And now we know: “The jeweler claims the chain pictured is Trent Williams’s, that contains 400–500 carats of black and white diamonds, and that it would be worth $100,000 — $150,000.”

Getting Your Head Stuck In A Jar Will Make You Thin

“A black bear that spent three weeks roaming Cocke County with a large plastic jar stuck over its head has been released in the Cherokee National Forest 85 pounds lighter but otherwise unharmed.” Also, they took the jar off.

Tobias Wolff And The First Novels That Writers Wish Were Forgotten

Tobias Wolff And The First Novels That Writers Wish Were Forgotten

Out of pique or posturing authors occasionally disparage their early work. Saul Bellow referred to his pre-Augie output, Dangling Man and The Victim, as his Masters and PhD, respectively; “I find them plaintive, sometimes querulous,” he told The Paris Review. Anthony Burgess, 23 years and 30-some-odd novels after the publication of A Clockwork Orange, groused, “The book I am best known for, or only known for, is a novel I am prepared to repudiate,” and impugned it as “a jeu d’esprit knocked off for money in three weeks[.]” John Steinbeck was only slightly more charitable towards Cup of Gold: A life of Sir Henry Morgan, Buccaneer, with Occasional Reference to History, his 1929 first novel, calling it “an immature experiment written for the purpose of getting … all the autobiographical material (which hounds us until we get it said) out of my system.”

Other authors, not content with self-mockery, take matters even further. Nathaniel Hawthorne falls into this camp. Fanshawe, his first novel, which he published anonymously shortly after he left college, was so obscure — thanks in no small part to Hawthorne himself, who purchased copies just to burn them — it was unknown even to his wife. To this modern hack, it seems rather nutty of Hawthorne to send Fanshawe to the pyre just because the work happened to resemble Sir Walter Scott’s. His stubborn presentation of The Scarlet Letter as his cherry-popper, despite its publication 22 years after Fanshawe, suggests that writers do indeed worry that readers will, as Francine Prose put it in a 1992 Washington Post article on this phenomenon, “confuse their apprentice novel with their first.”

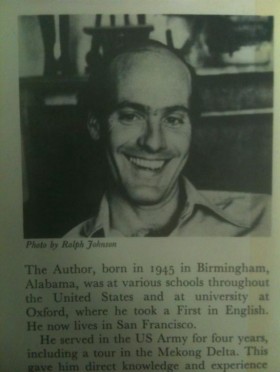

One such worrywart is Prose contemporary (and one-time subject) Tobias Wolff, a master of the short story and memoir. In 2003, the promise of what Publisher’s Weekly called a “first full-length novel” from the author of This Boy’s Life and In Pharaoh’s Army was cause for excitement. His publisher, Knopf, played up what appeared to be an unprecedented departure: Famous short story writer births a novel! To this day, Knopf’s marketers describe Old School as a “shrewdly — and at times devastatingly — observed first novel.” And that’s almost true — the book is, in fact, perfect — but the blurb’s second-to-last word is a lie. It elides the existence of Ugly Rumours, a novel Wolff published nearly 30 years earlier.

If you haven’t heard of it, don’t feel too bad. Wolff’s 1975 novel has escaped the attention even of individuals for whom books are a livelihood. “It doesn’t ring any bells to me,” said the bookseller at Bauman Rare Books, who noted that the store’s copy (which can be yours for $1800) hadn’t moved since 2002. When I called the Strand, an irritated buyer told me that, no, he hadn’t heard of it, either. As for the New York Public Library, its single copy has been requested only once in seven years.

My initial interest in Ugly Rumours was a happy accident. In 2003, my boss at The New York Observer, displeased with my initial attempt at a review of the as-yet-unpublished Old School, ordered a rewrite — one with a little bite, if you please. The disclosure that Knopf had taken some liberties in their promotion of the book (discovered in ten minutes on LexisNexis) did the trick. How odd, I thought, that a writer whose output was marked by such clarity would allow an early work to be obscured. Only recently was I able to obtain a copy and see what had so bothered Wolff.

As befits a book that reportedly had a print run of less than a thousand, not much is known about the publication of Ugly Rumours. It was published only in England, by George Allen & Unwin in 1975, and retailed for £3.25. The book was written after Wolff returned from Vietnam and entered Oxford University, where he wrote two novels, one of which was lost “without any grievance on my part.” Ugly Rumours was reviewed twice, by the Times (UK), who compared it to Richard Hooker’s MASH, and praised the book’s climax as “realistic and horrible,” and The Times Literary Supplement, which sniffed that “too much of the novel prefers to avoid treating gravities gravely.” (London Review of Books chose to slag it in 2004). An advertisement for the book also appeared a single time in The Guardian.

And that’s it. Its publisher, George Allen & Unwin, no longer exists, at least not in any recognizable form. Shortly after Ugly Rumours came out, the house was absorbed by an Australian outfit. Asked for details about the book, the company professed ignorance (entirely believable) and sent me a Wikipedia link to the entry for Ugly Rumours. All traces of Wolff’s novel, pre-publication, appear to be gone.

This seems a shame. Wolff’s readers, most of whom will understandably refuse to shell out $1800 for the army green hardcover, are denied the pleasure of observing the true arc of a great author’s career. Predating Wolff’s Vietnam novella The Barracks Thief by nine years, Ugly Rumours is about two Special Forces buddies, Christopher Woermer and Stanley Grubbs, who attempt to survive their tour via “favourable assignments,” i.e., no combat. It’s an earnest narrative, following the men from the States to Vietnam — Wolff’s claim to have been influenced by Thomas Pynchon notwithstanding, it is not at all postmodern.

There are small traces of later Wolff, in both narrative and style: Woermer’s irritation in the novel’s opening pages at being called ‘college boy’ may remind readers of Anders’ rage at being addressed as ‘bright boy’ in “Bullet in the Brain”; the description of an Oakland Overseas Replacement Depot building that “memorialized the Depot’s only flirtation with contemporary standards of taste” is of apiece with modern-day Wolff’s lovely, nearly airless sense of humor; the concision of a scene in which Woermer lies to an English war correspondent:

Woermer, in desperation, tried to explain how it felt to have a mine go off almost under your feet, the sound so loud you could not hear it, the sudden lightness of body, all of it. But the right words would never come . . . His imagination took over from his memory. He led the scribbling Englishman through tiger-infested jungles, escapes from entire divisions of hardcore Vietcong, and daring daylight raids on enemy headquarters. Woermer told these lies without pleasure, because he saw the reporter had no respect for truth.

The book is far from perfect. Woermer and Grubbs are frequently indistinguishable and other characters are caricatured beyond belief. Some of the dialogue given to Sergeant Andrews, a black man — “Whuffo you want me to let you go, way you puts the bad mouth on me when I’m not here?” — is cringe-making and the writing is sometimes purple. But still, the child is very much father of the man.

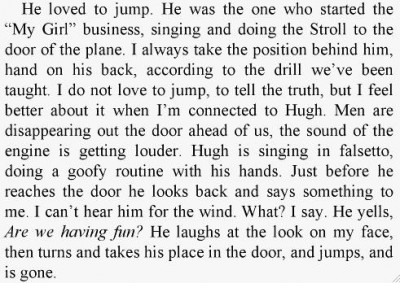

The ends of Wolff’s works, memoirs and otherwise, are always disarming and beautiful. My favorite happens to be In Pharaoh’s Army, in which Wolff memorializes a dead friend:

The conclusion of Ugly Rumours, while not a gut-punch of that caliber, nonetheless recalls in its brutal simplicity the close of All Quiet on the Western Front. In a way, the horrific loneliness of being one of a mass of men dying in a foreign land as conveyed by Remarque is made even less bearable here, because Wolff, rather than leaving the reader with an image of our dead protagonist, spends the last moments with his murderer:

The Ranger stared at Woermer’s shuddering body. Then, like a man waking from a long sleep to find something unclean in his hand, he looks at his rifle. He dropped it and melted into a sea of cripples.

I don’t believe this is writing of which Wolff ought to be ashamed. But over the years, he’s repeatedly deployed a single adjective to describe Ugly Rumours: “terrible.” When asked about it in 2003, around the time of the publication of Old School, he told The San Francisco Chronicle, “I can’t just bald-faced sit here and say to you that I haven’t written another novel,” lamenting that it “turns up now and then in booksellers’ catalogs, sometimes for five times what I was paid for it — not because it’s good but because it’s rare. It’s like a postage stamp of which only three copies survive or a gun that Colt only made two of.” (In that same Post article mentioned earlier, novelist Ron Hansen mentions that Wolff once asked him — “as a friend” — not to read it.)

I emailed Wolff in the hope that he might want to discuss the work. He replied:

I appreciate your interest in this novel, and respect your judgment, though I must confess it is very different from my judgment. I have no wish to spoil anyone’s pleasure in a book, especially one of my own books; it’s like serving someone a meal and then badmouthing it and mocking your guest for liking it. It’s just that I have no feeling for the book now, no interest in it, and no interest in attracting attention to it by talking about it.

Elon Green writes supply-sider agitprop for ThinkProgress and Alternet.

Apocalypse A Lot Easier Than We Thought It Was

“The cataclysmic extinctions that scoured Earth 200 million years ago might have been easier to trigger than expected, with potentially troubling contemporary implications.”

The Most Hilarious Clarence Thomas Opinionating Yet

If you haven’t had a chance to read Clarence Thomas’ dissent in Brown v. Entertainment Merchants Association, which was decided in late June, you have denied yourself good times! Our Special Correspondent for Supreme Court LOLs breaks it down for us, and it’s GREAT STUFF.

thomas’ core argument is that the court’s holding assumes that first amendment protections apply to speech directed at minors, which thomas thinks is WRONG WRONG WRONG…. he explains his theories of constitutional interpretation, which he supports by citing his own opinion in a previous case, an opinion that not a single other justice joined! in case that citation was insufficient, he then… cites another opinion of his that no other justice joined!…. this is a BOLD move.

but all of this is just a warmup. we are still getting to the fabulous part. this is the part when thomas starts talking about what thomas jefferson believed about raising his children. and thomas is talking about this because, in his mind, we have to use exactly the interpretation of constitutional language that the founders did — which means we have to imagine exactly what they would have thought, looking at the historic record to guide us. and so thomas, with scrupulous attention to every detail of jefferson’s parenting practices, totally fails to mention any of jefferson’s children except the white ones he had with his wife.

Boredom Will Make You Thin

“Eating the same foods, day after day, may make you so uninterested in your meals that you start eating less, a new study suggests.”

What's Invisible At Harvard: A Conversation

by S.J. Culver and Kaya Williams

Last week, The Paris Review’s blog ran “Harvard and Class,” a piece by Misha Glouberman (co-authored by Sheila Heti) about the challenges of dealing with class after attending “an upper-middle-class Jewish day school” in Canada and then going to Harvard — which, hmmm! As two recent Harvard grads ourselves, we wanted to offer a slightly different perspective on class, race and the Ivy League, as well as what it’s like to be offered $40 by your peers to remain invisible, please.

SJC: The first thing I thought of while reading the article was Dorm Crew [a student-run cleaning service]. You were one of the first people I met at Harvard — we both signed up to do Dorm Crew the week before freshmen normally arrive on campus. In retrospect that was one of the few prescient choices I actually made while at Harvard — it sucked, but it helped me meet a lot of people from backgrounds similar to my own straight off the plane.

KW: Oh man! Dorm Crew. It seems like so long ago, and I think part of that is actually because the experience of Dorm Crew was so very different from the rest of my experience at Harvard. When we finished that week, I thought, “This is a thing I could keep doing as a job while I’m at school.” And it paid pretty well, and I did it for about a year, and during that year I realized, “This is not socially acceptable, apparently.”

SJC: SAY MORE.

KW: Okay, so I signed up for Dorm Crew like, pretty quickly, because it just seemed like the obvious choice. I didn’t really have any other options for having money upon starting school. It seemed like “having money” would be a good idea, and “getting a job” in a city I had never been to before seemed impossible. And everyone was so cool! We listened to Michael Jackson all day long and cleaned, and it was really fun, and I remember thinking, “These people are not intimidating, they’re pretty normal.” And everyone was from somewhere different. It was actually really diverse, and it didn’t really dawn on me until a while later that that’s not reaaaaally what Harvard is like.

SJC: I signed up for the same reasons, but it seemed fishy to me from the start that there were all these pre-orientation programs, and you could, like, shell out $400 to do a week-long arts program or an outdoor camping trip, or you could get paid $8 an hour to clean toilets for a week. It was better to do Dorm Crew at the end of the year, I think — you found all the stuff people left behind after moving out of their dorms. A friend found that Burberry scarf once; people would leave crazy stuff, couches, televisions, appliances. I think I got an Ethernet cable. I was juiced. Those things were $10!

KW: Oh yeah, I FORGOT. That is such an interesting and crazy thing, that as you clean rooms, you find all of these often-expensive things that graduating students just LEFT BEHIND. And you can keep them if you want. Someone on my crew found a tennis racket and said, “Sweet, I’ll sell this on eBay.” It was like, “How fun! Plunder!”

KW: But also, that’s insane.

SJC: Yeah, Dorm Crew is actually a good shorthand for the class situation at Harvard. To some people the service is totally invisible, and to most of the people doing it (at least, to me) it is a window into a world that is equally invisible. A world where you’d abandon a brand new Burberry scarf ($325).

KW: Yeah. And a TV. And a tennis racket. And a winter coat. Because they’re “just too big to move.”

SJC: Scarves do take up a lot of room. Do you think the reason you found it uncomfortable to do Dorm Crew during the semester was that you actually had to enter occupied rooms and clean classmates’ bathrooms, instead of just cleaning up after people had already left for the year?

KW: Yeah. That was a big part of it — but I don’t think it’s only that, because when I decided to do it during the year, I thought, “It COULD be awkward cleaning the toilets of your peers, but I don’t think it will be.” The culture they tried to create around Dorm Crew was “it’s respectable to work”; it makes sense to get paid to do something useful while you’re in college; doing “service” work is not something to be looked down on. And I kind of just thought you’d show up to people’s dorms and they’d say, “Yeah, I did Dorm Crew too.” But actually a very small percentage of people do it.

I also suspect that one of the reasons dorm crew even exists is to save Harvard the money they would have to spend hiring unionized workers to clean the bathrooms. Because then they would have to pay for benefits like healthcare. So you’re actually simultaneously helping Harvard to fuck over its domestic workers AND being judged as inferior by your peers. Which is all very complicated and difficult to deal with as an 18 year old, really.

[I]t seemed fishy to me from the start that there were all these pre-orientation programs, and you could, like, shell out $400 to do a week-long arts program or an outdoor camping trip, or you could get paid $8 an hour to clean toilets for a week.

SJC: Right, and the theory behind Dorm Crew is probably also motivated by a healthy dose of the “working for your education teaches you character, and cleaning toilets teaches you even MORE character!” line of thinking, which is its own separate Harvard problem and is reflected by many other financial negs that constantly only affect people who have little money — yet were intended to teach all of us about sacrifice, character, etc. I HAVE SO MUCH CHARACTER NOW, THANKS. That’s why I’m taking part in this classy conversation, dissing our alma mater.

KW: There’s this myth of self-sufficiency and pulling oneself up by the bootstraps that is cultivated obviously not only at Harvard, but Harvard is such a great way to hyperbolize it: You, Harvard Student, are no different from anyone else in this country. You could start with $0 in your pocket and through hard work and ability become the president one day. All you have to do is avoid the temptation of spending all your money on take-out. Feel great about the fact that you’re here, because it means you’re smart and not lazy like all those poor people out there who didn’t make it to Harvard. It definitely has nothing to do with privilege or social capital.

SJC: I believe you have my favorite Harvard story about secret wealth. Several of my favorites, but I’m talking about the car one.

KW: Wait, which car one? I’ve already forgotten it.

SJC: The one where the chick from your section had the secret Escalade? That her parents paid for her to park at the Charles Hotel all year? To me that was the epitome of Harvard class interactions: everyone seems relatively normal, then all of a sudden you find out the person next to you in lecture has a Cadillac they pay to park at a four-star hotel.

KW: There are so many stories like that. And it’s not as if everyone at Harvard is super-rich, although certainly plenty of people really, really are — but you feel discouraged from talking about class. So everyone ends up assuming that their peers are “just like them,” because they are just like you in the sense that they’re 18, and scared about taking college classes. And it’s only when things accidentally slip out that you realize you have very little in common OTHER than Harvard. I feel like the only place I ever really got to talk about class was with other students in the black community, because it’s impossible to talk about race without talking about class, so we learned to be pretty honest with each other.

SJC: In my experience everything about class was silent and coded. It would slip out in weird ways sometimes. Once I had invited this professor (who shall remain unnamed, but who was, for the record, a genuinely smart and lovely person and a dedicated teacher who gave me the first A I ever got on a paper at Harvard), to a faculty dinner. We were making small talk. He asked me where I was from. He asked me what my parents did, and I said they were a nurse and a cop. This was, junior year? Now I’m embarrassed to admit I didn’t get an A until junior year, but whatever — it was far enough in that I had figured out that lots of people in the Harvard community were weirded out by jobs like “cop” and “nurse” even though I had always thought those were really pretty middle-class jobs? Ah, naïveté. I still remember the look on this guy’s face — and he said, in possibly the most weirdly condescending tone possible, “Oh, how interesting. So how do they feel about you being at Harvard?”

KW: Jesus. Yeah. I don’t think I ever told anyone what my parents even did. I told people my mom was a teacher and left it at that.

SJC: Oh my god, is your mom not a teacher?

KW: No, she is. But even when we first got there, it was very apparent that “teacher” might be acceptable, although “professor” was preferable, and that I should only tell people my dad was a construction worker, and that he had passed away, if I wanted to suffer through the worst conversation of my life. Because that was zero people’s experience. And no one knew how to react.

SJC: Before and after college I felt/feel extremely lucky to have had the background I have. But there? It was essentially my first experience learning that class didn’t necessarily correlate with money.

KW: Exactly. One of the things Harvard does train you to do is to fit in. You don’t want to make a scene when people are putting on their big display of middle/upper class-ness. And even if you did want to make a scene, there’s almost no language in America to assert the idea that being from, say, working-class, rural America doesn’t make you the butt of some joke or another, without falling into the equally problematic language of “real America” and “Wall St. vs. Main St,” etc.

SJC: And trying to fit in just ends up meaning you’re not a part of ANY group, which was the saddest part of Glouberman’s article to me. This line: “There was someone who was the first person in her town to go to Harvard, and she talked about how this completely tore her apart, and how the whole time she was at Harvard she always felt out of place and everyone treated her badly, but when she went home everyone thought she was stuck-up so she felt out of place at home, too.”

I think a lot of what we’re talking about now is not Harvard itself, but Harvard as a lens for what happens when you get stuck between class “spaces” in America. There is probably a social sciences word for class “spaces.” Feel free to insert it.

KW: Actually, there’s not. Social scientists LOVE the word “spaces.”

SJC: I also want to talk about that ONE SINGLE LINE about race in this piece.

KW: God.

SJC: Let’s see: “There was this African American guy who described a kind of racism that had been invisible to all of us.”

KW: SO MANY THINGS are wrong with that sentence. 1) You feel so uncomfortable using the phrase “African American” that I can feel your discomfort through the computer screen; 2) what the hell, “us?”; 3) despite the fact that he told you, you obviously didn’t listen because you can’t describe the racism — you can only call it “a kind of racism;” 4) it was invisible to all of you.

SJC: The “us” really gets me there, as well. Was every single other person at that panel white? Literally, no one had been confronted with their own privilege before then? This reminds me of the house dues debacle, actually. How did that even start?

KW: First, there was an email about the house formal, which is ever so fancy — and such a nice way to train your young little Harvard students to go to black tie events and swing dance with champagne. Anyway! To go you had to pay “house dues,” which were, let’s say, $40.

SJC: And if memory serves, the event was so popular they would lock down the entrances to the house for two days around the event so people couldn’t sneak in. Meaning if you didn’t buy a ticket it was actually a hassle to get into or out of your home for a while. Plus the obvious problem of being excluded if you couldn’t afford the $40.

KW: And since they didn’t sell the tickets through Harvard’s official box office, the financial aid fund for student events couldn’t be applied. And I thought that must be a mistake. So I sent an email to the house open list saying something like, “Hey, I can’t remember but I thought there was a financial aid thing for this — if you’re on financial aid what should you do?” and happily left the house thinking, “When I get back someone will have answered my question.”

SJC: Oh, innocence.

KW: When I got back, there were a billion emails waiting, each angrier than the last. People were fighting about whether the cost was too high or whether $40 was “not even much money,” and blah blah blah. So I sent another email, thinking, “This has just been a misunderstanding.” It read something like, “Hey guys, sorry for unsuspectingly causing a scene, I just wanted to know what the policy is. Can anyone tell me?”

SJC: But it wasn’t a misunderstanding.

KW: It was not. The two emails I remember most vividly are: 1) the girl who informed me that a Subway had just opened in Central Square, and if I didn’t have $40 maybe I should get a job; and 2) the guy who said he’d “pay me $40 to stop bitching.” Seriously, what the hell?

SJC: And the thing you sent back, which I remember vividly, explained that you already had not one, but two jobs.

The whole thing seemed structured to teach you, “Yes, as long as you can talk loudly and confidently enough that everyone shuts up and listens, you have the right to tell me I don’t have any rights.”

KW: But the icing on the cake was that after that, me and another friend get called to go down to talk to THE HOUSE MASTER (…because no one thinks that title is problematic), because we were being disruptive on the house list and they didn’t want a fight. Overall, he was nice, and agreed to put monitors on the open list and not make us pay for the formal, but at the end of the day it was still a situation where my friend and I had to explain why we were mad and ask for help. Whereas the people who actually said incredibly classist and racist things, did not, in fact, have to answer for their actions.

SJC: Typical Harvard. Happy to throw money at problems when you point out they exist, but there is very little “let’s teach people how to be respectful” or “let’s be proactive about potential conflict” in this situation where everyone’s interacting with people with very different backgrounds for possibly the first time.

KW: “Oh, you’ve been demeaned constantly every day you’ve lived here? Here’s $40. Enjoy the chocolate fountain.”

SJC: I remember having “discussion section” for a course being just baffling to me, too. It’s pretty much the exact opposite of a working-class public school classroom: you get taught there — and at home, if your parents are like mine — that the teacher/authority figure is in charge, infallible, and should be listened to without interruption. Being told to discuss 400 pages of Clarissa with my classmates at Harvard was like being asked to do this completely alien thing, opposed to everything that had been scared into me about the way education works. So basically I sat there for four years seething, thinking, “Why are my parents paying quite a bit of their hard-earned money for this unwashed grad student to sit back and watch me talk?”

KW: The current grad student in me wants to point out that I do actually shower regularly, but yeah, I think that’s really interesting. In my freshman writing class we had to read Plato’s Allegory of the Cave, and then tell the professor what we thought, and I just remember thinking, doesn’t this guy know the answer? Why is he forcing me to sit here and listen to assholes go on and on about something? But I think a lot of it is really training people that they have a God-given right to voice their opinion on any subject. Because we all know Harvard turns out a lot of politicians. And you need that skill.

I remember another infuriating moment in a moral reasoning class; we were having a “debate” about what counts as a human right and what doesn’t. And this guy was going on and on about how education is not a human right and here’s why, and it just dawned on me that one day this guy is going to have a job in government. The whole thing seemed structured to teach you, “Yes, as long as you can talk loudly and confidently enough that everyone shuts up and listens, you have the right to tell me I don’t have any rights.”

SJC: TALK LOUDLY WITHOUT AN ACCENT AND PEOPLE WILL LISTEN. And now we have serious opinions on Harvard and class which we want other people to read, so I guess that the system works? Did this conversation just eat its own tail?

KW: Yeah, I was just thinking, why bother writing a thing; people will just think, “Oh look you Harvard douchebags, writing another thing about Harvard.”

SJC: I agree, BUT I do think that for one reason or another people actually read things written about Harvard (see: social capital), and those things don’t tend to be written by people with this perspective, really. Unless it’s really sensationalized and made-for-TV-movie-ish.

KW: True. Harvard also teaches you how to act as though you are more worthwhile than other people, despite the fact that it doesn’t teach you much of anything worthwhile. Which is why it’s no wonder people who didn’t go to Harvard immediately try to prove to you they’re more worthwhile than you, upon realizing you did. I have had my feelings hurt more than once by someone who thought they were elevating themselves to “my level,” but actually it just felt to me like they were putting me down for no reason — when what was actually going on was “Harvard.”

SJC: You know, our five-year reunion is next spring. I was pretty opposed to going for, oh, all of the reasons covered above, but a friend was in town last week and we fell into talking about how Harvard was a miserable place to go to school in a lot of ways, and probably only the people whose entitlement it most rewarded were going to go to the reunion, and she said, “Fuck it, we can’t let them take our reunion. It’s our reunion too. We have to go.” I mean essentially we ARE Harvard as much as the people who fit the archetype — they let us in, so we don’t have to buy the myth…

KW: …that we don’t belong?

SJC: Exactly.

KW: I will go to the reunion, because that is the thing — it might have overall been a horrible institutional culture that teaches you terrible things about class and race, but there were also a lot of people there who were smart and kind and self-aware who learned to be critical of that culture. And I would like to see all those people again, and have drinks with them at Charlie’s Kitchen, whilst eating waffle fries.

SJC: And if Harvard grads are going to “run the world,” it could very well be people who think the same way we do. It will not be me. I’m too lazy. But it would be a real shame if we just ceded that social capital Harvard does convey to the people who were loudest and acted most entitled.

KW: Wouldn’t it be nice if one day Harvard was just a school and not all of these things people like to imagine it is? But as long as it is all of those things, we don’t do anyone any good by allowing them to believe that the only people who come out of it are upper class, white and hate you.

SJC: We should make t-shirts. “I went to Harvard, and I love you.”

S. J. Culver is a writer with limited web design skills. Kaya Williams is probably a graduate student somewhere.

The Science Of Glassing

British Science takes on glassing!

Engineers at the University of Leicester have for the first time created a way of measuring how much force is used during a stabbing using a broken bottle. The advance is expected to have significant implications for legal forensics…. Stabbing is the most common method of committing murder in the UK. Injuries and assaults related to alcohol consumption are also a growing concern in many countries. In such cases the impulsive use of weapons such as a glass bottle is not uncommon. In approximately 10% of all assaults resulting in treatment in the United Kingdom (UK) emergency units, glasses and bottles are used as weapons. Official UK estimates suggest that a form of glass is used as a weapon in between 3,400 and 5,400 offences per year. There is little understanding of how much force is required to create the injuries as, until now, there have been no systematic studies of how much force is required to penetrate skin with such weapons.

But now… there is. Oh happy day!

"In the punishing heat of a July afternoon, dresses are 'the ultimate in comfort'"

So how sure are we that the Times piece on dresses isn’t actually an Onion article? http://nyti.ms/pRxy8qThu Jul 21 14:44:38 via web

marc tracy

marcatracy

Um, not at all sure. “Younger women, who once adopted the dress as a cheeky send up of mid-20th century feminine stereotypes, are now dispensing with such ironies and acknowledging the frankly sensual appeal of the dress.” WHAT IS GOING ON.