Should Millennials Ever Grow Up?

The false distinction of generational compromise.

“To be grown up is to sit at the table with people who have died,

who neither listen nor speak.”

—Edna St. Vincent Millay

There are so many articles — ”think pieces” or “blogs,” as Grown-ups accustomed to print media might derisively refer to them — about the uncertain fates of Millennials. Millennial media is a cottage industry devoted to chronicling Millennial woe. “Won’t anyone think about the Millennials?” goes the near-universal lament. “Whenever will they find themselves?”

But consider the lives of their counterparts, the Grown-ups. Those Grown-ups have family responsibilities, budgets to balance, back deck extensions to order, beach-houses to rent, and other pressing problems. Millennials, at least in theory, have mostly vague, existential complaints that can be ignored indefinitely: retirement and social justice issues will be hashed out one day, but probably not today and definitely not by the Grown-ups in charge, who have more immediate, “real-world” problems: private school tuition, soccer practice, and the morning commute.

To be a Grown-up, then, is to have been harried and aggravated into a state of public indifference. Encounters with Millennials frequently terminate in questions about the Millennial “finding themselves” in part because, as Paul Goodman observed sixty years ago in Growing Up Absurd, “it becomes clear that people are uneasy about, ashamed of, the world that they have given the children to grow up in.” In Goodman’s opinion, his own generation of Grown-ups had failed to give their kids “a more worthwhile world in order to grow up at all.” Instead, they had become cogs in an immense system, apathetic and overworked drones unable to make life in America bearable for young people who are coming of age in it:

Is it possible, how is it possible, to have more meaning and honor in work? to put wealth to some real use? to have a high standard of living of whose quality we are not ashamed? to get social justice for those who have been shamefully left out? to have a use of leisure that is not a dismaying waste of a hundred million adults?

Despite admirable gains in areas such as civil rights and gender equality, Goodman’s concerns were never fully addressed during his lifetime (he died in 1972), and remain unresolved today. Then, as now, the ball was in the Grown-ups’ court — but they were too overwhelmed with trivial tasks to accomplish everything they needed to do.

The Grown-ups rush to compromise because they are always rushing, hurrying here and there. Their perpetual motion on the hamster wheel is something we will “understand when we’re older,” and embracing cynical indifference appears to be the crucial dividing line between feckless Millennial and reasonable Grown-up. Other features that might evince maturity, such as having children or owning a house, appear incidental to becoming a Grown-up; what matters most of all is arriving at the conclusion that there are no alternatives to the status quo.

I’d be lying if I claimed I didn’t occasionally fantasize about being a Grown-up. How nice it would be, I daydream, to fret over my cratering mutual funds and a sunroom extension I can’t afford and attending to my cholesterol levels! It doesn’t matter that all of these worries are tedious to the point of exhaustion: a Grown-up is always out of breath from running in place, and so never able to talk with friends (who has the time?) about widening income inequality and looming ecological devastation. Like them or not, these petty Grown-up annoyances would indicate I had progressed from one stage of life to another. I would have matured, become a person of substance, and could begin desperately trying to stockpile assets while awaiting the peace of the grave.

Up to this point, I have passed through most of the life cycle that defines 20th century America: childhood — a “priceless” period in which I was allowed to imagine things while consuming cheap plastic toys — adolescence — when I listened to angsty music and assumed I could change the world — and then…full stop. I stalled at Millennial, always a few minutes late to my appointment with the other Grown-ups.

But childhood, far from being some mythical status existing from time immemorial, was actually a historically contingent stage. For most families, children were once units of labor, tiny adults who could be employed on the farm or, following industrialization, in mills and factories. In Pricing the Priceless Child: The Changing Social Value of Children, Viviana Zelizer demonstrated how legal changes gradually removed children from the workplace, as the nation’s growing affluence enabled mass-scale education and sentimentalization of the young, even as the need to keep these priceless babes (fewer in number than ever before, since quality now mattered more than quantity!) supplied with toys also led to an increasing “monetization and commercialization of children’s lives.”

And the restless, searching era of the automobile-supplied teen of the late 1950s, the period critiqued so sharply by Paul Goodman in Growing Up Absurd, was another social construct. Middle-class teens, who were really just adults not yet ready for the workplace, found themselves with a little cash in their pockets, some gas in the tank, and nowhere to go, both literally and figuratively. Teens were allowed to “discover themselves” before accepting their fates as Grown-ups, a process that has increased in duration following a late-1980s boom in graduate and professional-school attendance and a corresponding rapid decline in the number of entry-level white-collar jobs available to college graduates.

All of this culminates in the caricatured “woke Millennial” of 2016: a lost soul studying intersectional texts and supporting doomed candidates and utopian reforms, their receding years drawing them ever closer to the void even as some of their savvier peers opt out, join the system, and become full-fledged Grown-ups (as happened to every prior and seemingly pure youth movement, from Beats to Gen X’ers, that grew old). It’s a shabby state of affairs, one in need of radical change.

In Growing Up Absurd, Paul Goodman gets the diagnosis right, but his proposed cure doesn’t go far enough. We shouldn’t ever want to become Grown-ups. None of us should want their lives, because their lives are merely lengthy, chore-filled preludes to the nursing home and the cemetery: an endless string of pointless tasks that preclude them from ever addressing important ones. Instead, we should work to rid ourselves of thinking in terms of categories like “child,” “tween,” “teen,” and so forth. Age is only a number, not some all-important advertising metric that determines whether we want to rent UFC pay-per-views or use Cialis, and it should be treated as such.

One of the positive developments of the past decade is the growing recognition that identity ought to be affirmatively chosen, never imposed from above. And though these labels for life stages might fit like an old shoe — they’re the way they are because that’s how they always were — that doesn’t mean we need to follow them. Even as individuality is paramount, collective responsibilities shouldn’t be sloughed off because you’re late for some school play or a bridge closing has added thirty minutes to your commute.

Labels have a tendency to take on lives of their own, and a refusal to accept being branded as old, out of touch, and needlessly, endlessly “busy” may well preclude people from embracing such a slide into that sad second act of their existences. Prior generations have faced the same choices, and some courageous-minded folks have held the line: tired beats, worn-out civil rights crusaders, old hippies, aging gay liberation activists, flannel-clad scene kids from the 1990s who refused to “sell out.” But being forced to choose between working to solve chronic social problems and merely hanging around is no choice at all, and we ought to leave such decisions in the dust.

Sasha Obama Was A Really Good First Teen

A celebration

Tuesday, Barack Obama gave his last speech as President live from Chicago, Illinois. It was an emotional occasion for all of the obvious reasons, and First Lady Michelle Obama and Vice President Joe Biden were among the attendees. But a lot of viewers were surprised when, at a certain point in his speech, the President addressed daughters Malia and Sasha and the camera panned to reveal that only Malia was there. “Where is Sasha????” Twitter screamed. Just that question. Where is she? Keyword search it. People were revved up.

It’s being reported that Sasha had a science exam Wednesday morning, which makes sense because everyone just got back from holiday break and that’s exactly when teachers are like, “Lol time to own u.” Remember that move? It’s rude. But also, “I have a test” is an age-old parent-proof excuse not to have to do some shit you don’t want to do. Family reunion? Craaaaap I have this project. Aunt Gina’s forty-third birthday party? Ughhhhh drivers’ ed! Regardless of whether or not Sasha actually needed to stay home and study, her absence confirmed something I’ve been appreciating throughout her dad’s eight year presidency: Sasha is a really good first teen.

She was seven when her dad became President, and she’s only fifteen now, so she’s never been old enough to have an arrested-for-having-a-fake-ID moment like the Bush twins or an interning-at-“Girls” moment like her sister. Sasha’s just… regular. America’s little sister. She scooped ice cream on Martha’s Vineyard as a summer job. She wore a choker and lip synced all the words when Chance the Rapper performed at the White House Christmas tree lighting ceremony.

And while her older sister Malia seems to share their parents’ affinity for continual camera-readiness and extreme composure, Sasha always looks how I imagine I’d look if someone tossed me in a pea coat and made me watch a turkey pardoning: disinterested but doing my best to hang.

happy birthday to a hero: sasha “never once been here for your photo op” obama

Often, the Obamas disembark a plane in coordinated looks. It’s a nice photo opportunity, and you know every time you land in a place the local paper wants a nice portrait of the first family for their front page. But while the rest of the Obamas would lean into the visual, sporting matching blue and yellow florals, or three different takes on gingham, Sasha would be wearing… all black.

Michelle Obama stages her own London Fashion Week http://t.co/OXIS9sripK

— @nytimes

Sasha Obama had to miss her father's farewell address because she has an exam Wednesday morning, White House says. https://t.co/EsIBvyHxHe

— @ABC

Can’t you hear the argument now? It’s every argument any teen has ever had with their family in the history of time. Yelling down a White House hall, “I NEVER ASKED FOR THIS, MOM!!!!!!” and slamming a door. “Accidentally” “forgetting” a gingham jumper in the closet and sliding a black dress into the suitcase instead. Our emo queen. Our fifteen-year-old selves.

The same way that I hope Malia was smoking weed at Lollapalooza, I’m glad Sasha ditched her dad’s work event for whatever reasons she had. Coming of age is wild, and doing that with the world’s eyes on you, braced for you to be breathtaking and inspirational in the face of some truly wild circumstances, is something I cannot imagine would be fun day-to-day. So yeah, study for your test Sasha. Stay home on a Tuesday. Peak teen. Best teen. America’s teen.

J. Cole's Authentic Inauthenticity

When kitsch thinks it’s rich

Last month, North Carolina rapper J. Cole released his fourth album 4 Your Eyez Only. The reviews were notable less for their praise than for their cagey, sheepishly qualifying disclaimers. “In one of hip-hop’s most populist periods, he is a divider — a loyalist to out-of-fashion values and a conscientious objector to dominant trends,” wrote The New York Times’s Jon Caramanica. “Snowblind loyal subscribers will flock to crown Cole as a generational superhero,” wrote Jesse Fairfax on HipHopDX, “While lazy detractors won’t soon be swayed from steadfast views that he’s human Hip Hop Nyquil.”

At Vulture, Craig Jenkins identified Cole’s latest music as “proof he buys into the defender of the faith business as much as his listeners do, but neither party seems to understand that rap flourishes better without strict rules and boundaries.” The headline of Paul A. Thompson’s Pitchfork review read, “On J. Cole’s fourth album, he wrestles with the fragility of life and the importance of family ties. He also sands down some of his worst impulses.” Hardly glowing recommendations for one of rap’s most visible stars, the auteur who, to quote hip hop’s most enduring meme, infamously went platinum with no features.

“J. Cole Went Platinum With No Features” Is the Best Meme Right Now

For the last half decade, J. Cole has enticed and confounded listeners, inspiring vocal partisans on both sides. The dispute is predicated less on the question of whether or not J. Cole is good — some of our most essential rappers are not good by quantifiable metrics of technique, creativity and charisma the keys to their triumphs, and what is good anyway? — than on whether or not he is the type of good he so passionately purports to be. That is: an emblem of ambitious sophistication upholding the tradition of rap’s venerated lyrical maestros.

J. Cole maintains a scholar’s appreciation of the high-church hip hop of his youth. As a middle American child of the Reagan presidency, his primary influences are Nas, Jay-Z, and 2Pac. He treats the most literary rap of the mid-1990s with a religious zeal, and is in many senses an adept mimic of his idols. A fallacious reading would be that because he sounds like Nas and Jay-Z, who are good, then J. Cole is also good. The flaw in this logic is that Nas and Jay-Z were imperfect human artists, and J. Cole has been most successful in cribbing their least meritorious elements.

Even as an adult Nas personified the precocious innocent, compiling dispatches from his broken world — a projects Peter Pan with a notebook. Rather than his omniscient Hemingway-esque detail and the capacity to squeeze life from his characters’ little tics, J. Cole aped his ham-handed concept songs. In attempting to replicate Jay-Z’s impenetrable bombast, Cole fatally overlooked its predication on the narrative understanding that Jay-Z was a drug dealer before he was a rapper (the second of multiple hustles he’d go on to master). For J. Cole, rap has always been the be-all and end-all, success and fame pursued for their own sakes in a circular ambition that would have doomed his heroes.

Cole’s apologists cite his reverence for the craft, but even as a dutiful student, he managed to whiff on many of the critical details. The condensed J. Cole origin story is that he moved to New York and stalked Jay-Z until he was offered a record deal, a weird perversion of Jay-Z’s own rags-to-riches tale. For Jay-Z, rap offered a chance to turn legit. His appeal lay not in his posturing but in the skills and priors which legitimized it, an Alger narrative which Cole misinterprets. Jay-Z’s gusto is an effect, not a cause, of his greatness. J. Cole is what Jay-Z might sound like if he’d spent his adolescence listening to his own records instead of living them.

If this supplies ammo for critics who label Cole boring or corny, his delusions of grandeur are further undermined by the everyman persona he inhabits. He is, by his own accounts, something of a regular guy with a regular life, which, when expedient, would make him a refreshing alternative to his most grandiose peers. Yet the melodrama and braggadocio with which he laces his first-person accounts are not only out of scale, they stand in direct opposition to a character which demands humility and self-deprecation.

Cole is, too frequently, a walking, rapping paradox. His 2014 single, “No Role Modelz,” a five-minute slut-shaming screed, opens with the “Fresh Prince”-invoking clunker, “Rest in peace Uncle Phil, for real, you the only father that I ever knew / I get my bitch pregnant, I’ma be a better you.” He raps of the late pop star, “My only regret, could never take Aaliyah home / Now all I’m left with is hoes up in Greystone.” When convenient he is an advocate of tolerance, but he deploys pejoratives “retard,” “bitch,” and “faggot” as naturally as other rappers do ad libs, which wouldn’t be so notable or deplorable in itself if not for the fact that hardly any rapper is as self-righteously moralizing as Cole is. “She shallow but the pussy deep,” indeed.

Even when not toeing the line of political correctness his dearth of self-awareness manifests itself in bewilderingly tone-deaf moments. “Wet Dreamz,” another 2015 single, is a guileless account of losing his virginity. On paper it promises to be a self-effacing subversion of machismo, but the performance is so bereft of humor it borders on sociopathic: “You know that feeling when you know you finna bone for the first time / I’m hoping that she won’t notice it’s my first time.”

Cole aspires to ambitious distinction, all but shouting it from a mountaintop, but rarely delivers. He sounds passionate when his words are vapid. His love songs are too ravenous to seem heartfelt. A 2013 song was structured as an open apology to Nas for recording a derivative pop song which the legend evidently found repugnant. Cole’s punchlines are appallingly dreadful and discomfitingly reliant upon fecal references. His worst offenses are so egregious that they all but disqualify his music from consideration.

There is a running back who was born the same year as J. Cole named Shonn Greene who spent most of his professional career with the New York Jets. Greene weighed 230 pounds and was a unanimous All-American at the University of Iowa. He didn’t attempt to run around defenders so much as run through them. This often made him exciting to watch, because he might as easily truck-stick a hapless defender, or at least drag him a few yards, as get stuffed at the line of scrimmage. The problem once he reached the professional ranks was that NFL defenders are really good at tackling, and Greene didn’t improvise well, usually running in the direction the play was drawn even when his blockers blew their assignments. For Jets fans, it eventually became infuriating that a player as talented as Greene couldn’t or wouldn’t do something as elementary as attempting to run around people trying to tackle him. Shonn Greene was strong, fast, powerful, and fearless — all traits, if not base qualifications, of good running backs — but he wasn’t a good running back.

I don’t mean to distill this to J. Cole Equals Shonn Greene, but both had many of the necessary credentials (upon receiving his one-page resume, the HR department is very excited about J. Cole), really good intentions, and really bad instincts. Cole aspires to rap’s most traditional high-art variants. Punchline rap, usually structured in rhymed couplets with a conventional comedic setup followed by a play on words in the latter bar, is a time-honored craft which has produced some of the most entertaining components of the New York hip-hop canon. Autobiographical and narrative rap are laudable endeavors which often produce gripping, revealing music. But Cole’s ambition is not sufficient in itself, and he is usually a punchline rapper with terrible punchlines, a memoirist with no self-awareness, and a storyteller without subtlety.

This rationale applies to most any job or medium. Mechanics and aspirations do not a great writer make. Nor is sophistication restricted to the sort of hyper-articulate rap J. Cole favors, which when affected poorly plays like nails on a chalkboard. Juvenile, Too Short, Suga Free, and E-40, for example, are timeless, iconic rappers for their artistic explorations of decidedly un-lofty subject matter, all the more so because they recognized the function of rap as entertainment. A middling writer of literary fiction or a mediocre arthouse auteur is not superior to an elite YA novelist or a director of great slasher films. Cole is an above-average technician with such disproportionate megalomania that, as a commercial artist, it offsets his strengths.

In a parallel universe very much like ours J. Cole is very good, and it’s only after you spend some time there that you begin to see the seams of this Bizarro World. J. Cole might be a savant for his successful shrouding of populism as sophistication. He blends so many elements of beloved rap acts that a passive listener might confuse them. He fuses the simulated artifices of his childhood favorites with Kendrick Lamar’s cinematic scope. His punchline setups and obsession with fame are reminiscent of Big Sean. His lusty ballads, more longing than loving, bear resemblance to Drake’s.

This conflation is, of course, brilliantly deceptive. “Life Is a Highway” sounds like a Springsteen song to the point where its structural and aesthetic similarities almost mask that it’s a four-and-a-half minute discourse on a single senseless aphorism, containing none of the poetry or poignance that separates Springsteen from a Canadian impostor. As a storyteller, Cole’s oft-cited analogue Kendrick is a master of nuance, a self-conscious spectator forever trying to skirt the destructive impulses endemic to his native Compton. Cole lacks Kendrick’s shattering empathy, his signature, unshakeable bafflement that children grow up to be shitty adults. Next to Big Sean, a cockeyed clown prince, Cole’s eager-to-please goofiness is conspicuously absent, and his ballads are as self-pitying as Drake’s, sans the Torontonian’s mercurial showmanship. Even Wal-Mart sells clothes that look like designer brands.

Carl Wilson’s Let’s Talk About Love: A Journey to the End of Taste, a 2007 entry in the 33 ⅓ series, attempts to answer a simple question: How could Wilson, a person paid to have opinions on music, find a pop icon as ubiquitous and revered as Celine Dion so awful? He undertakes a historical and geographical survey attempting to crack the lock on middlebrow culture, the naive guilty pleasures of Thomas Kincaid and Oprah’s Book Club. His is the timeless search in the competing ethics of poptimism and rockism, the ticking of Disco Demolition Night. He is High Fidelity’s Rob Fleming rifling his dinner host’s CD racks for a mark, or David Herman’s character in Mike Judge’s Office Space, a web-coding misfortunate named Michael Bolton, despairing, “Why should I change my name? He’s the one that sucks!”

One of Wilson’s earliest clues is the concept of schmaltz, a mainstay in pop from Tin Pan Alley through Manilow and Streisand. “Schmaltz is an unprivate portrait of how private feeling is currently conceived,” he writes. “Under the surface of popular music, greasing its rails, the secret history of schmaltz runs in oleaginous currents, awaiting deeper exploration.” This might explain why Cole’s dramatic, unspecific accounts can taste like Kendrick’s, even if once digested they offer the nutritional value of fast food.

The Ringer’s Shea Serrano has written at length on the J. Cole phenomenon, and attributes Cole’s appeal to the Barnum effect, “the observation that individuals will give high accuracy ratings to descriptions of their personality that supposedly are tailored specifically for them but are, in fact, vague and general enough to apply to a wide range of people.”

“I don’t think he’s actually relatable,” Serrano wrote last month. “I think he’s a familiar version of relatable, which people confuse with the real thing.”

J. Cole is, of course, thoroughly middlebrow, and his steadfast maintenance that he is the highest of the highbrow is perhaps his most grating quality: on record he has proclaimed himself the equal of Rakim and Ice Cube as well as a superior to Slick Rick and Big Daddy Kane. Yet his broad empty-calorie appeal bears likeness to the one Wilson perceives in American Idol and Celine Dion.

“American Idol attracts critical venom almost as much as Celine herself, and for many of the same reasons,” he writes. “For all the show’s concentration on character and achievement, it is not about the kind of self-expression critics tend to praise as real.”

Instead, Wilson writes, it celebrates “‘Authentic inauthenticity,’ the sense of showbiz known and enjoyed as a genuine fake, in a time when audiences are savvy enough to realize image-construction is an inevitability and just want it to be fun. ‘Authentic inauthenticity’ is really just another way of saying ‘art,’ but people caught up in romantic ideals still bristle to admit how much of creativity is being able to manipulate artifice.”

Despite Dion’s complex Quebecois identity, Wilson notes that her multilingualism eschewed immediate regional characterization, and survey data suggested that her listeners were disproportionately likely to be poorer, older, uneducated, widowed, and/or LGBTQ, a practical silent majority of disaffected mankind. J. Cole is biracial and from North Carolina, effectively anywhere and nowhere, a “living here in Allentown” blank canvas for whatever reflections on society he wishes to make. He is 32 but looks and sounds 23, and is a southerner who raps like a New Yorker, except when he raps like 2Pac, when he’s not rapping like Kendrick or Drake.

As others have already written, 4 Your Eyez Only is better than it ought to be, which, paradoxically, is really the best thing one can say about it. It is leaps and bounds better than 2011’s Cole World: The Sideline Story and 2013’s Born Sinner. It contains some adequate 2Pac karaoke, and the best songs have a dusty vinyl warmth, which inspires the stark intimacy suggested by the album title. Cole is still not nearly as profound as he thinks he is, and needs coaching on the concept of “show don’t tell”: when he says he wants to cry, the listener mostly has to take him at his word. The chorus of the third-act ballad “Foldin’ Clothes” repeats the stone-faced proclamation, “I want to fold clothes for you.” (Sexy!) It’s an atmospheric record with competent scene-setting, and although its characters are types, so are most actual people. Cole has improved considerably, but probably shouldn’t have been afforded the opportunity.

In Let’s Talk About Love, Wilson relays an anecdote from the 1998 Academy Awards in which the late Elliott Smith, himself a detractor of Dion’s, encountered her backstage and found himself floored by her ineffable charm and generosity, saying afterward, “It was too human to be dismissed simply because I find her music trite.” Sure, her music sucks, but don’t we all?

Who Is Marconi Union?

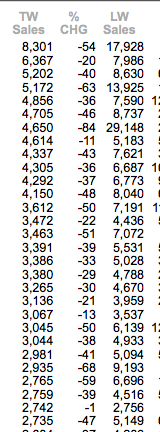

Soundscan Surprises, Week of 1/5

Back-catalog sales numbers of note from Nielsen SoundScan.

The definition of “back catalog” is: “at least 18 months old, have fallen below №100 on the Billboard 200 and do not have an active single on our radio.”

Toto, we’re not in Christmas anymore. It’s January and back catalog sales are back in the toilet. Nearly every single record experienced a negative percentage change in sales from the week prior, because once Christmas is over I guess we just stop shopping. The numbers have taken such a dive that the top five records’ sales are down 54, 20, 40, 63, and 36 per cent, respectively. That’s rough! The only two albums to experience positive growth on the back catalog did so because their sales numbers increased relative to zero, which is to say it was their first week on the charts. Pity the poor souls, Chicago(’s Very Best Of), and Marconi Union. The latter is an “ambient music trio” from the UK. According to their website:

In 2011 MU were commissioned to write a piece of music that people would find relaxing. They received consultation from Lyz Cooper a Sound Therapist, who advised them on some of the technical issues relating to how the human body responds to sound.

Mm, yes, body sounds. This sounds exactly like what you’d expect to hear when you walk into a purple-lit room with sensory deprivation tanks. Please do not enjoy this music video of a UFO drone with lights hovering over a mountain lake and continuously multiplying until it becomes physically uncomfortable to behold and you start to ponder the nature of your existence, and also light reflected in pools of water:

The top-selling record (Vessel by Twenty One Pilots, who still don’t have a hyphen in their name) clocked in at 8,301 copies. The only Christmas albums left are Pentatonix (TWO of them), Charlie Brown (Vince Guaraldi, I know, I know) and Michael Bublé, and both the fact of their existence on the charts and their rankings is a lot to marvel at.

Did you know there are four and one third versions of The Essential Bob Dylan? There’s the standard American version, released in 2000—a two-disc set that received an additional disk in a “limited edition 3.0 version” in 2009. Then there’s the British and Australian versions, which are significantly longer and include more songs in slightly different order because that is how the British Empire likes it. Then there were re-releases (new versions? Hard to say what’s new except like “updating your Bob Dylan playlist in iTunes to include maybe one new weird song”) in 2010 and 2014. This latest “2014 Revised” comes in at #200, because Bob Dylan will always be relevant, especially now that he won the Pulitzer, but even more so when he dies, whenever that is, because you need to realize right now that’s going to happen one day. Just get ready. Oh and George Michael died, remember 🙁

4 MICHAEL*GEORGE FAITH 5,172 copies

7. PENTATONIX THAT’S CHRISTMAS TO ME 4,650 copies

25. MICHAEL*GEORGE TWENTY-FIVE (2CD) 2,935 copies

26. MICHAEL*GEORGE LADIES & GENTLEMEN-BEST OF GEO 2,765 copies

45. CHICAGO VERY BEST OF: ONLY THE BEGINNING 2,334 copies

84. GUARALDI*VINCE TRIO CHARLIE BROWN CHRISTMAS 1,585 copies

90. MARCONI UNION WEIGHTLESS (AMBIENT TRANSMISSION) 1,555 copies

105. PENTATONIX PTXMAS 1,487 copies

164. MICHAEL*GEORGE SYMPHONICA 1,155 copies

198. BUBLE*MICHAEL CHRISTMAS 1,066 copies

200. DYLAN*BOB THE ESSENTIAL (2014 REVISED) 1,059 copies

(Previously.)

Hauschka, "Familiar Things Disappear"

Yes we can even

Over the last twenty-four hours you may have seen several variations of the following points in your social media feeds: 1) Can you believe this? 2) Is everything going to be like this all the time from now on? 3) Is this real life? and 4) I can’t even. I know you are fragile and confused right now, so let me address each of them in at attempt to help you cope with your new environment.

- Can you believe this? Yes, you can believe it. Even if it is not true you can believe it. You have heard every man with a platform and an unerring belief in his own authority go on about the post-truth era in which we now live and, at the risk of affirming these self-propelled wind farms, I have to admit that they are correct. In this era you should probably believe everything, because almost anything that we thought was too crazy to be true wound up happening. Also, and this is more important, nothing matters anymore. Regardless of how ridiculous or offensive or outright inhumane any behavior would have been considered in the past it no longer carries any weight, particularly with the people who would be been the most vociferous in denouncing it in earlier times. It is no longer important whether something is technically true or not: Everything is true enough, and none of it makes a difference anyway.

- Is everything going to be like this all the time from now on? Yes, everything is going to be like this from now on. The present moment, in fact, is the most sedate and reasonable that things will be. It’s good that so many people have spent so much of their time watching reality TV over the last decade, because now that every aspect of American life will follow along the lines of its cheap manipulations and tawdry twists we will all be somewhat more prepared for each successive revelation. If there is still a civilization a decade hence we will look back at the way things once were with shock and incredulity. The past will be unrecognizable and any accurate depiction of earlier norms and conventions will be dismissed as propaganda and deceit.

- Is this real life? Yes, this is real life. I don’t like it any more than you do, but this is it. I understand your asking the question, but deep down you already know the answer. There are two truths you need to remember going forward: 1) Everything is terrible and only getting worse, and 2) That’s it, that’s the deal, it’s just getting worse, don’t look for a second thing to save you. You could certainly choose to get Baudrillardian if you are desperate enough to deny reality, but have you ever seen someone reference Baudrillard who wasn’t a Grade-A asshole? You have not. This is real life. Sorry.

- I can’t even. Yes you can. You do all the time. Human beings are programmed to get used to it. It requires an incredible level of strength, resilience, determination and discipline to resist, and those skills are needed every second of every day in spite of terribly dispiriting odds and a crippling sense of isolation that comes from watching everyone around you acquiesce and go on with their lives. Do these sound like attributes that are prominent in your make-up? Do you feel as if you are one of the very few people who are able to bear these burdens and endure these discomforts when it is so much easier to simply submit? Of course not. You totally can even. Most of us can even, and do.

There you go. I hope I’ve answered all your questions. Now let’s have something new from Hauschka, whose What If is out at the end of March. Enjoy.

New York City, January 9, 2017

★★★ The children, bundled up in the packed and stalled elevator, began shedding hats and coats mere moments after it had ground to a stop a few inches past the 29th floor, while the loudest adult was still yelling into his phone for help. It had barely gotten warmer than usual before the doors were pried open and the escapees clambered over the offset, dropping stray gear on their way to the freight elevator. A thin glaze of cloud covered the sky, and a thin glaze of salt covered the pavement. The two-day-0ld snow, light though it was, had hardened and survived. The stains on it were numerous and vari-colored, but they were still separate and individual marks, on a still-white background.

Lusine, "Just A Cloud (feat. Vilja Larjosto)"

I’ve been listening to this all afternoon.

What’s your feeling on vocal treatments? I know some people who dismiss them out of hand. The first pitch that gets shifted, they’re gone. If you are that sort of listener you might find this track a bit trying, but please try. After a couple of minutes of potential discomfort everything will begin to loop into itself and the resulting blend will be captivating in a way you did not quite think possible back there at the beginning. I mean, at least I hope it does. Some people just don’t like that kind of vocal manipulation no matter how much magic comes from it and I guess I have to respect that. The rest of you, however, should enjoy.

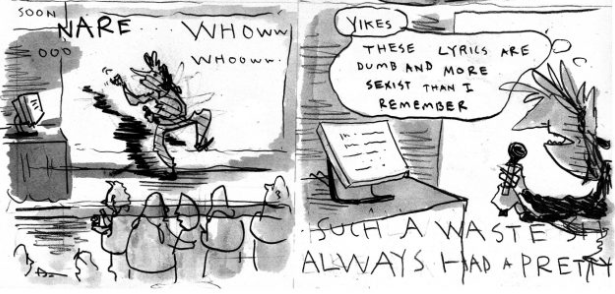

Click For Comics

A cartoon a day keeps the bad news slightly further away.

Awl pal Sara Lautman is hosting a week of diary comics over at The Comics Journal; today is day two (already day one has brought a relatable Karaoke conundrum).

You may recognize Lautman’s drawings from last year’s “Uncomfortable Objects,” or the eternally useful “How To Hold A Grudge.” Lautman is an artist living in Baltimore; her drawings have been published in The New Yorker, Tablet, and Jezebel. Her most recent collection is The Ultimate Laugh.

Do Cats Like Fried Chicken?

An Australian experiment in carnivorous attraction

A parks department in Victoria, Australia is under investigation this week because supervisors finally noticed staff had been using the company credit card for non-parks-related activities. Concerning charges found on the statements include $347 at a jewelry store, $898 at a mountain bike shop, more than $5,000 at a Best Buy-esque home entertainment store, and thousands of dollars at a high-end hotel and spa. All of this seems like some pretty straightforward “we’re going to fire our dumb employees” stuff, but one part of the investigation really stands out to me.

The team also charged $260 at a local KFC over seven visits, and instead of being like, “Hey, we were hungry and got some team lunches,” they’ve made the genius claim that all of the chicken was used to address the nation’s feral cat problem.

According to the Guardian:

A senior Parks Victoria staff member, who did not wish to be named, explained to Guardian Australia that “KFC is widely known to be the most effective bait for luring feral cats”.

The genius of this is that Australia’s cat problem is very real—feral domestic cats were reported to “devour an estimated 75 million animals every day,” and had “wiped out about 28 native Australian species” as of 2015. So if these parks employees were, say, the kind of people who would use government funds in order to solve problems inside of the nation’s parks, they might ostensibly be spending on things like feral cat bait.

In supporting their claim, though, the team has had to make a case for why KFC is effective cat bait, which means that a bunch of Australian doctors and scientists are now weighing in on whether or not cats like fried chicken.

Dr. Alan Robley, a senior scientist with the Arthur Rylah Institute for environmental research in Victoria, explained that, “Fried chicken is included in the national guidelines for trapping feral cats and is used due to its scent and prolonged freshness.”

Dr. Christopher Dickman, a biologist and feral cat expert from the University of Sydney, confirmed “it is a popular bait with a strong aroma that is very attractive to carnivores.” But also, “There hasn’t been any data published on it so the information we have is anecdotal, but it does work for luring feral cats, though mainly in urban areas… Cats in remote areas are more suspicious of new foods, but cats in urban areas are more used to living close to KFC outlets and are familiar with the smell.”

So while that anonymous parks source might have been optimistic with the “widely known” part of their fried chicken explanation, it’s definitely about to be more widely known. Fried chicken: doctor and government-approved cat bait.

Surviving Solitary And Everything After

Unimaginable strength in an unimaginable situation

This is a remarkable story about human suffering and human resilience. It does not make for easy reading, and the degree of admiration you will have for its protagonist’s ability to keep himself whole in inhumane conditions will be offset by the despair you will feel over the inhumane system in which he found himself and in which so many others continue to find themselves. Now you have been warned, but you still have to read it. Give yourself some time and a distraction-free setting and read it.