Leif Vollebekk, "Into the Ether"

What are you smiling about?

I’m still not all the way sold on this one — the lyrics can be a bit much (although I tend to feel that way about almost all lyrics; it is best to just hear them as valueless sounds) — but if you are looking for something to be sad about that is unrelated to all the obvious candidates on offer these days the vibe here is exactly what you’re looking for. Do with it as you will.

What Your Voice Really Sounds Like

It’s different, right? But why?

Here’s how your voice sounds in your head when you say something out loud:

“Brilliant! Genius! Smart smart smart! So important! No one would fail to be convinced by what I’m saying!”

Here’s how your voice sounds to other people when you say something out loud:

“Listen to how brilliant I am! I think I’m such a genius! Have I ever told you that I’m smart smart smart? You can really tell that I am sure I’m so important! Even though it’s pretty clear my opinions are no better than anyone else’s I am somehow under the impression that no one would fail to be convinced by what I’m saying!”

Why is that? Fuck if I know. Maybe this will help.

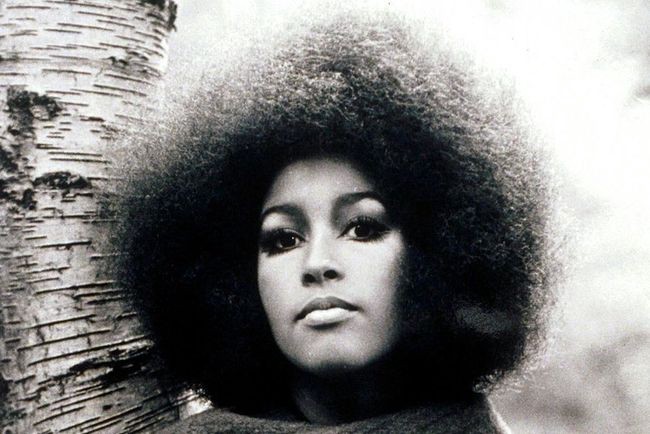

Best Forgotten: 'Real Life' by Marsha Hunt (1986)

Mick Jagger’s first and best baby mama

You’ve read about Mick Jagger’s most recent feat of paternity — in December he signed for baby number eight, with mother number five — so you’ve seen the name Marsha Hunt: a news story can’t inventory Jagger’s children without it. Hunt is the mother of Jagger’s first child, Karis, who was born in November of 1970, having gestated for a period roughly as long as her parents harbored affection for each other.

In articles I’ve read over the years, Hunt has always presented as self-possessed and disinterested in dwelling on her stratospherically famous onetime paramour. Still, because her name is forever reproductively linked with his, it’s been hard not to draw the conclusion that having Mick Jagger’s baby amounted to a career move. Recently, I tested this idea by tracking down and reading Hunt’s two out-of-print memoirs — 1986’s Real Life and 2005’s Undefeated — and I’ve reached a new conclusion: for Hunt, having Mick Jagger’s baby was probably a career dampener.

In 1966, the Philadelphia-born Hunt’s restless spirit lured her from her studies at Berkeley to London, then fully swinging; she never again called the United States home. “American politics and its class system, better known as racism, had shaped and limited my life and future in ways that I couldn’t know or fully comprehend until I was outside it,” she writes in Undefeated. “When I arrived in London…my nationality became my identity, and the Negro label took a back seat.”

Not that being an American black woman in London at that time didn’t have a certain cachet: “Motown was the sound of the day, and anybody looking and talking vaguely like a Supreme was considered gorgeous,” Hunt writes. In 1968 she landed a modest role in the London production of the Broadway smash Hair; six months later, she signed a record contract.

In Hair, Hunt sang a Supremes parody called “White Boys” backed by two West Indian women, and the white boys did come calling. Hunt briefly romanced Marc Bolan, when Tyrannosaurus Rex was just becoming T. Rex, and, nudged by her producer, recorded a couple of his songs. After scoring a minor hit with her debut single, Dr. John’s “Walk on Gilded Splinters,” she was contacted on Jagger’s behalf to find out if she would pose in a slutty getup for a publicity photo for the Rolling Stones’ forthcoming single, “Honky Tonk Women.”

Jagger had picked the wrong beautiful black woman. Hunt writes in Real Life, “The last thing we needed was for me to denigrate us by dressing up like a whore among a band of white renegades, which was an underlying element of the Stones’ image.” Hunt’s no to Jagger’s people inspired a phone call from Jagger, who paid her a visit that evening. She writes of their ensuing relationship in levelheaded terms — “We were not so much lovers as friends. There were no silly cat-and-mouse games” — and indicates that she wanted nothing in particular from him: “I needed my own independence and didn’t expect him to relinquish his.” She wasn’t even a Stones fan.

Meanwhile, Jagger was sufficiently besotted with Hunt to write “Brown Sugar” about her. She suspected he appreciated that she wasn’t into drugs, unlike his for-the-most-part girlfriend, the angelically opiated Marianne Faithfull. Hunt didn’t get too caught up in Jagger’s world: “I always feared that my association with him would crowd out my own identity. I never wanted to be known as Mick Jagger’s girlfriend.”

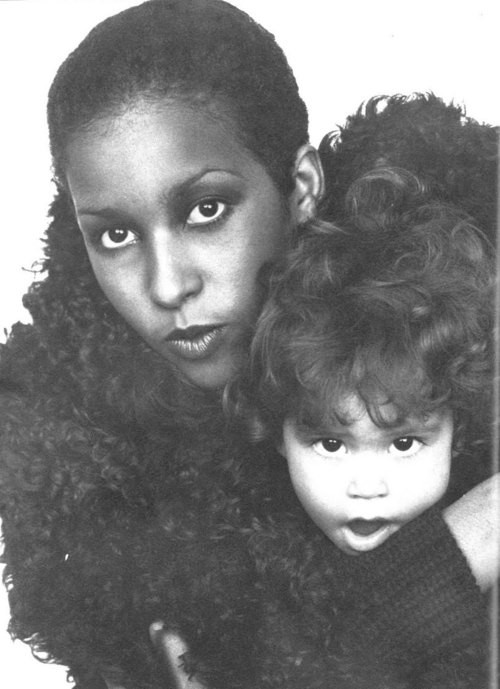

Well, she tried. But make no mistake: it was Jagger who proposed that they have a baby together. Hunt’s inkling concerning his motivation sounds just right, especially given subsequent media accounts of the long-standing Jagger-Richards rivalry: “Marianne had miscarried the baby that they would have had around the time that Keith Richard’s [sic] son Marlon was born. It was understandable that he considered having a second try.”

For Hunt, having a baby meshed with the day’s starry-eyed delusion that achieving happiness was a simple matter of letting the sunshine in: “I didn’t really expect it to change my life in any way. I was making money and had a lovely home. My prospects were excellent, and I was sure they’d continue to be so.” She and Jagger wouldn’t live together. As for his role in their child’s life: “We were supposed to be the sophisticated embodiment of an alternative social ideal — parenthood shared between loving friends living separate lives.” That’s hippiespeak for, “Mick and I made no financial arrangements regarding the support of our shared offspring.”

After Karis was born, Hunt scooped up pretty much any job that bounced her way, and not just music gigs: she modeled, acted in the dodgy English horror movie Dracula A.D. 1972, and did a soft drink commercial in Germany. The last was embarrassing, yes, but better than selling her story to the tabloids, and better than asking Jagger for a loan, as she had to do more than once.

Hunt made money on the road, and in 1972, while she and her backing band were on a German tour on which she had brought along Karis and a nanny, the toddler spilled hot tea all over herself. Hunt insisted on an immediate return to England, where she felt that Karis would get better medical care. This meant canceled gigs, which meant less income and less exposure to potential new fans. Hunt asked Jagger to spring for half of Karis’s hospital bill; the money never arrived. Despite the “sordid connotations” of a paternity suit, Hunt went for it: “After two years, I had to stop pretending that he would assume his duty.”

When the story went public, Hunt found herself something of a social pariah: “I went from being tagged ‘the girl from Hair’ to ‘the girl who sued Mick Jagger.’” She writes that she sensed a chill in the air when she interacted with shop people and the parents of Karis’s classmates. Hunt hadn’t tried to hitch a ride on a rock star, but if she had, her reputation would have scarcely emerged more sullied.

The paternity suit wasn’t resolved until 1979, when Jagger was told to provide Hunt with an annual settlement for Karis as well as a trust so that the girl wouldn’t be destitute if her mother suddenly dropped dead. Hunt personally received no money — fine by her — but everyone thought she had made off with a mint.

At the time the suit was resolved, Hunt was staying in Los Angeles, trying to find a distributor for a record she had made in Germany; to keep financially afloat she did housekeeping for friends while Karis was at school. When nothing happened in L.A., Hunt quit the music business, having promised herself that this would be her last go, since, as she wrote in perhaps the least diva-ish sentence in the entire world, “Music was only acceptable as a career if it could provide us with an income.”

Hunt redirected her creative energies to acting and writing. She has since published well-received novels centered on the African-American experience and an absorbing book about rescuing her long-presumed-dead grandmother from a U.S. nursing home. But the standout is Real Life. It’s flawed — it loses its bearings toward the end — but it’s an uncommonly clear-sighted account of the music scene of the 1960s and 1970s as witnessed by an inside-outsider disinclined to do anything that was expected of her. The book also reinforces an idea that I’ve long found to be true: a story about almost making it is usually more interesting than a success story.

At the end of Real Life, Hunt refers to her “charmed life,” but a reader may reasonably wonder, How so? Among Hunt’s disappointments: she blew a couple of film auditions, including one for Sidney Poitier, maybe because she was holding the script in one hand and Karis in her other arm; record contracts came and went or were not quite signed (“Managers and record-company people that I spoke to weren’t at all prepared in 1980 to accept that a [black] woman could find a market doing rock, which was considered white music”); and Richard Branson yanked funding for a musical she wrote because the London press said mean things about the dress rehearsal.

The “charmed” part of Hunt’s life, then, is presumably having had Karis, who surely, like every kid, couldn’t help but divert her parent’s attention from her work, deprive her of sleep now and then, interrupt her creative bursts, and so on. What stymied Hunt’s musical ambitions may have been not just a tarnished reputation and the business’s assumptions about black female singers but the fact that Karis was never not the first thing on Hunt’s — and only Hunt’s — mind.

A pulsebeat in Undefeated, which chronicles Hunt’s experience with breast cancer, is her anxiety about completing a book she’s been writing about Jimi Hendrix, who had been, like her, a black American in Britain in the late 1960s. She tells the reader that she doesn’t have a publisher, and at this writing I can find no evidence online that she has found one. If her Hendrix book comes out, may it get more column inches than news of the next Jagger baby.

Nell Beram is coauthor of Yoko Ono: Collector of Skies and a former Atlantic Monthly staff editor. She writes occasional Best Forgotten columns for The Awl.

Which 2017 NFL Playoff Quarterback is Most Elite?

A thorough examination of football’s most auspicious players.

As an adjective, the word “elite” still conveys something positive, even aspirational: elite athlete, elite model, elite travel services. But as a noun, embodied by actual living people, it has become one of the nastiest epithets in American politics.” — The New York Times Magazine

Joe Flacco is Not Elite. — The Washington Post

NFC

Dak Prescott (Dallas Cowboys):

Dak Prescott is built like the heavy machinery working-class white people operate for a living, which is the opposite of elite. But maybe he’s so adept at what he does, he is one of those machines that requires skilled labor—labor that’s not readily available in counties that voted for Barack Obama twice but then flipped to Trump because let’s just blow up the system instead of change jobs.

Moreover, Dak’s name, Dak Prescott, makes him sound like old money, like someone who will eventually have access to, and conflicts because of, emoluments. If Dak hadn’t become an elite quarterback, he could’ve done whatever the hell he pleased. Maybe his grandfather, who probably worked for the first Bush or was the first Bush, could get him a job trading securities or at the Today show or maybe Dak would just bartend and fuck around while living comfortably off his blind trust.

Many people argue that Dak is successful because the Dallas Cowboys offensive line is so awesome. Slot any quarterback, minus Tony Romo, behind that line, and the Cowboys are still 14–2. That’s fine. That doesn’t mean Dak isn’t elite. Elites are always protected. They always have more time to make decisions, more time to recover from mistakes and more time to feed the ball to Ezekiel Elliot. Dak is elite.

Russell Wilson (Seattle Seahawks):

Russell Wilson thanks God too much to be a true elite. Elites only thank their agents or their lawyers or other people who they hire to make them more money.

Russell Wilson used to play baseball, and kind of implies he would go play again if anything ever happened to his absurdly successful football career. At one time baseball was elite but now it’s just for immigrants and professors at small liberal arts colleges and kids who are comfortable with distant dads. Russell Wilson is none of these things. And so he must play baseball because he actually loves it. Loving what you do is elite. (That’s counterintuitive because elites also love to complain about what they do.)

Russell Wilson never complains about anything. He and his coach Pete Carroll are so upbeat. All they do is talk about how they visualize success and then express gratitude after the success occurs. Once in a while they’ll discuss vaccines and how they probably cause autism? But then Richard Sherman will shout from across the field house, “Russell, if I hear you denying the scientific truth of immune theory one more time, I will consider you less smart.” Richard Sherman does not consider Russell Wilson smart, but as an elite himself, he knows that sometimes it’s better to let people think you think they’re smart. It’s called “the bubble.”

Russell Wilson is also average height and hangs out with the creator of Entourage. Neither is elite.

Matt Ryan (Atlanta Falcons):

Matt Ryan attended Boston College, a Catholic school. Catholics are obviously not elite. Catholics are civil servants. The one time a Catholic became president, that president was assassinated by a non-Catholic.

The reason Catholics are not elite is they always figure someone is watching them, and so they act accordingly. Because the world is theirs, elites do whatever they want, at all times, unless what they want to do is eat at a franchise restaurant.

It’s easy to imagine Matt Ryan tapping on the hand dryer before he enters a bathroom stall, because he is too ashamed to be heard. Can you imagine Morning Joe, who is an elite, ever doing that? No. He is using the bathroom, and possibly watching porn on his phone, with the sound on, and definitely unrolling toilet paper so raucously that anyone even passing by in the hallway can hear what he is doing. Elites do not care if anyone is listening or watching or hacking. It’s why Hillary hid a server that could be hacked in her Chappaqua basement. Just kidding! Bill advised her to do that and he is trash (but disguised as elite).

Aaron Rodgers (Green Bay Packers):

Sometimes, during his Sunday Night Football introduction, Aaron Rodgers says that he graduated from Butte Community College. While this is true, it’s not the full story. Rodgers also attended Cal, an elite school, and you’d presume he’d be thrilled to always announce that, because elites love bragging about where they went to school. But don’t forget: the only thing elites love more than where they went to school is irony. Aaron Rodgers is extremely elite because he is willing to say he went to Butte instead of Cal, all for the sake of an ironic smirk.

Earlier this season the Green Bay Packers, and Aaron Rodgers specifically, were slumping. Some people, myself included, speculated that Rodgers was playing poorly because he was not speaking to his parents. Elites speak to their parents, basically, daily. Even distant dads who love baseball still speak to their elite children, even if it’s through the child’s mother or other primary caregiver.

Rodgers predicted to some reporter that his team would “run the table” on the rest of the season. How are you going to do that when you’re not speaking to your parents? Here’s the thing though. The Packers did frigging run the table. Making good on an insane prediction is very elite. Have you ever read or watched The Big Short? Elites worship counterintuitive prognosticators even at the expense of global financial systems.

Aaron Rodgers is also dating Olivia Munn, and they probably cried together when Hillary lost. Why couldn’t we run the table for Hillary, Olivia Munn asked Aaron Rodgers, as he texted his parents, I’m sorry I’ve been a dick.

AFC

Brock Osweiler (Houston Texans):

Brock Osweiler, a terrible quarterback, convinced a professional football team to pay him a truckload of money to be good at quarterbacking, something they didn’t really have a ton of proof he could be good at. Convincing people to act against their self-interest is elite.

Brock Osweiler was born in Idaho and grew up in Montana, scenic but not elite. And he played college football for Arizona State. Also not elite but he probably had a fun time, more fun than he would’ve had at Stanford where he could’ve gone, on scholarship. Sasha Obama will eventually make the same decision Brock Osweiler did and only then will we recognize ASU over Stanford as elite decision making. Good for you, Brock Osweiler. Sasha Obama is going to have a blast.

Ben Rothliesberger (Pittsburgh Steelers):

Big Ben is trash like Bill Clinton. His teammate Antonio Brown, however, is a god. So much so that Russell Wilson should thank AB, and not his own God, every time the Seahawks score.

Alex Smith (Kansas City Chiefs):

Alex Smith was first in his draft class, picked ahead of even Aaron Rodgers, and being valedictorian, even when Aaron Rodgers is the salutatorian, is elite. The San Francisco 49ers, now trash, used to be an elite team, with multiple championship titles, but when they picked Alex Smith, they were rebuilding, which is what elites say they are doing when they are failing.

Alex Smith is a game manager, a professional. Insert him into your offensive scheme and he will perform competently. He led the 49ers as far as he could, until Jim Harbaugh benched him in favor of Colin Kaepernick. This was before Colin Kaepernick knelt during the playing of the National Anthem and alienated himself from some elites and most non-elites.

But Alex Smith joined the Kansas City Chiefs, and with Coach Andy Reid, they’ve regularly appeared in the early rounds of the playoffs. Resilience can be an elite quality assuming Alex Smith has learned to be resilient not through prayer but via Tim Ferris podcasts.

Tom Brady (New England Patriots):

Of course Tom Brady is elite. He attended Michigan, which is like if the 92nd Street Y also had a football stadium where Jim Harbaugh worked. Kids at Michigan walk around with t-shirts that say “Harvard: the Michigan of the East.” Can you imagine being so self-aware and so self-deprecating and simultaneously so arrogant? That’s the trifecta of elitism, and Tom Brady embodies it.

Trolls, especially in Buffalo where I live, like to mock Tom Brady for endorsing and wearing Uggs. But I’ve only ever seen him wear the Uggs slippers, and wearing slippers—particularly outside in the wintertime, like running to Latin class from your boarding school dorm in New England—is very elite. The boys from the Dead Poets Society, for instance, would absolutely wear slippers if the movie were set today. Instead of sucking the marrow out of life, and seizing the day, they’d ironically wear indoor shoes outside, in the middle of January, and stare at their phones, Venmoing each other money for the anxiety medicine they bum from each other. That’s because, as elites, they love irony as much as they hate anxiety. Besides, Tom Brady wears Uggs because Uggs pays him to do so, and making money is always elite.

It is possible Tom Brady voted for Donald Trump. He never really said, one way or the other, as far as I can tell. Gisele seemed to get pissed he wouldn’t deny voting for Donald Trump, and if you’re not vehemently denying you voted for Donald Trump, you’re basically a troll from Buffalo, or worse, an Iowa farmer who refuses to learn to operate a Dak Prescott. Neither is very elite. But he’s won four Super Bowls and unfortunately is about to win a fifth, now that Eli has been eliminated, and even if he couldn’t have done any of it without Bill Belichick, when have elites ever refused help from people smarter or more evil than they are?

Telling The Bees

Talk to the hive before it’s gone.

This week the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service added the rusty patched bumblebee to the endangered species list. It marked the first time that both a bumblebee and any bee species at all has received that designation in the continental U.S.—in other words, the hive collapse mania you’ve been reading about these past few years is finally reaching a point where the government is intervening. “The bees,” they essentially said this week, “are dying way too fast.”

U.S. Puts Bumblebee On The Endangered Species List For 1st Time

Being listed as endangered grants the species “protected status,” which will go into effect February 10. That status includes requirements for actions like federal protection and the development of a recovery plan, and it also means that states with habitats for this species are eligible for federal funding.

Anyway, all of this sent me down a bee Wiki k-hole and delivered me to a custom called Telling the Bees that I just think is so nice. Historically, beekeepers give life updates to their bees and then read the behavior of the hive in the weeks afterward as a sort of omen. Neglecting to update your bees about your goings-on is said to potentially result in hive abandonment. So even if I don’t have anything as major as a wedding or a death to report on, whispering, “I have seen both episodes of The Bachelor this season,” might still be an extension of the custom. Had I not chatted with my bees, after all, they might get offended and stop waiting around for me to talk to them. Look:

The telling of the bees is a traditional European custom, in which bees would be told of important events in their keeper’s lives, such as births, marriages, or departures and returns in the household. If the custom was omitted or forgotten and the bees were not “put into mourning” then it was believed a penalty would be paid, such as the bees might leave their hive, stop producing honey, or die.[1] The custom has been most widely noted in England but also recorded in Ireland, Wales, Germany, Netherlands, France, Switzerland, and the United States.[2][3][4][5][6]

So if you live in the rusty patched bumblebee’s remaining habitat, try talking to them every once in a while. They might just miss you.

Anjou, "Soucouyant"

It will have to be the little things from now on.

It’s Friday, you made it, it’s a long weekend. We don’t need to belabor what comes after. It’s Friday. You made it. It’s a long weekend. Let that be enough.

Here’s eleven minutes of semi-ambient music with lightly menacing undertones. Will it help? Who knows? But lightly menacing is so much better than the level of menacing you are used to these days that it can’t hurt. Enjoy.

New York City, January 11, 2017

★★★ The rain had passed overnight, and the morning was well on its way to drying out. A greasy dampness still clung to the tiles of the subway station, though. Grabbing the parka had seemed easier than thinking about what else to grab, but it was a mistake. On a fresh-air break, it was possible to pull the supplemental hoodie out of it and use that alone. The people passing on Fifth Avenue had no clear consensus on what to do with their down or their furry ruffs.

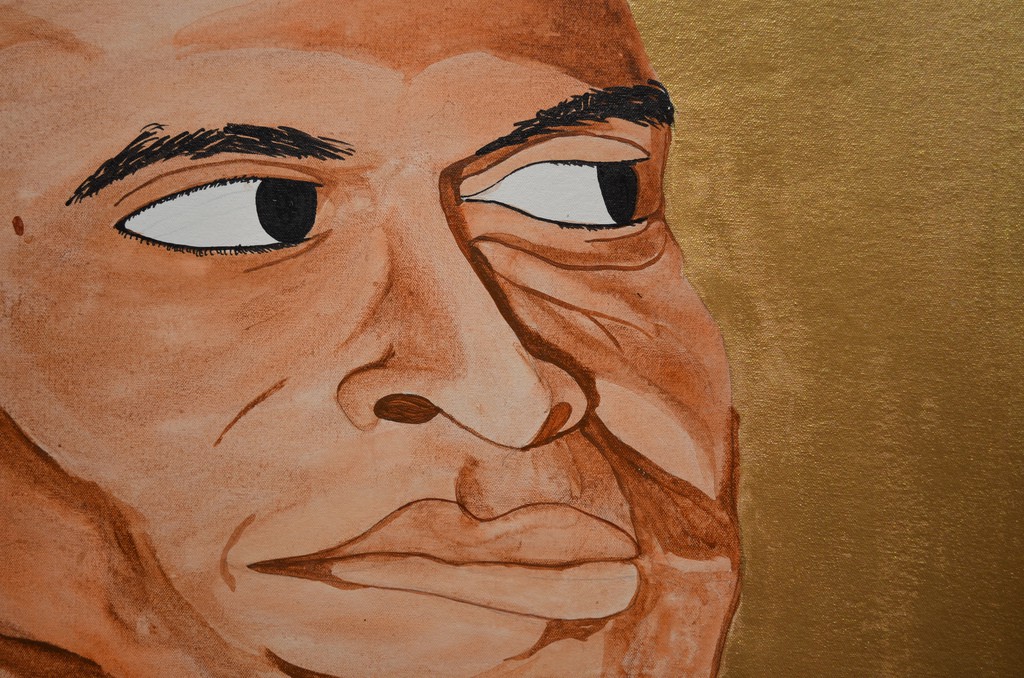

Alienation and Freedom

The life and work of Frantz Fanon

If you’re reading this there’s a decent chance you have read Frantz Fanon’s The Wretched of the Earth or know that you should have done and feel bad about not getting around to it yet. Good news: An unread classic is an occasion for joy, not shame, since it represents a fresh opportunity to be moved by a work of profound genius. Anyway, this lengthy piece by Adam Shatz, pegged to a new assemblage of Fanon’s previously uncollected pieces, functions as both potted biography and intellectual introduction and is a good place to start if you are about to work your way up to Wretched and a great refresher course if the passage of time has somewhat dimmed your recollection.

LRB · Adam Shatz · Where Life Is Seized: Frantz Fanon’s Revolution

You Can't Make Me Stop Using Q-Tips

Why aren’t we listening?

This week, health and medicine site STAT posed a question that gets asked a lot:

So I’d like to write down the answer someplace once and for all:

Because our ear canals are full of earwax.

At this point it’s probably safe to assume that many of us have heard, “Don’t use Q-Tips!” and maybe even “You’ll damage your hearing!” during our journeys through time and space. And yet, it seems, we do not give a shit. Why is that? Because we spend every waking hour combatting all of our other orifices, so it seems unseemly to just let one of them… be itself.

If there were a buildup of wax around your eyes, you’d wipe it off. Same is true of your mouth or your butt or your bellybutton. It’s part of our social contract to vigilantly monitor our secretions so that we can appear professional, fuckable, and sane. So turning that reflex off when it comes to your earwax buildup can be a hard habit to kick—like biting your nails.

The same way a lot of us will still eat sugar even though we know it’s poison, a lot of people are going to secretly clean their ears whether it’s dangerous or not. Having a body and a brain at the same time is complex. It’s fine.*

_____

*But also be safe out there tyvm.

Award Tour

A Tribe Called Quest’s latest release, in context.

The first time I heard A Tribe Called Quest’s “Check The Rhime,” I was on a basketball court in Houston. I was not overburdened with handles. No jump-shot to speak of. But it wasn’t long before some truck’s bass swallowed my courtside anxiety, enough to pull me and everyone else on the court into a lilt. Tribe sounded punk. A little funky, too. Except no one had ever heard anything like it. I missed lay-up after lay-up, jouncing every second pass, but it didn’t matter. Just being black kids on the court in the middle of the city, before Facebook but after Y2K, was a celebration in itself — cause enough to break into chorus. Like someone was rhyming simply for the sake of getting you through the day. It isn’t a feeling I’ve gotten from another record since.

A Tribe track brews a very specific emotion, a particular brand of confidence: a clean, untouchable thing. The group honed that aura for a little over a decade, across five albums, before their initial dissolution in 1998. When they released their first record in 1991, Phife Dawg (Malik Taylor) couldn’t have legally scored a brew. He was carving out his role between Q-Tip (Kamaal Ibn John Fareed) and Ali Shaheed Muhammad, on the verge of re-molding America’s soundscapes. And yet, despite their youth, and the beginnings of inter-group conflict, and the vertigo of the musicians’ burgeoning success, they penned verses like this one, this one, and this one, upper-cutting the ceiling they set for themselves again and again.

Their latest record, We got it from Here… Thank You 4 your service dropped three days after the presidential election. Q-Tip and Ali Shaheed performed on SNL the next evening. The group claimed it would be their final album, their first since Phife’s death from complications with diabetes earlier this year (they had recorded his verses in the months prior). And the release felt like a blessing of sorts, albeit a strange one. That a group preaching non-conformity and coexistence on every record (save one) should re-materialize after the election of its literal antagonist felt pretty fucking weird.

So I passed on it that first week. And then the next one after that. I treated the SNL spot like a pop-up, dodging Tribe and all conversations concerning them. But when I finally did get around to listening, in a roundabout trip for gas, I pulled onto the highway to take the tank as far as it would go. Three listens through the record, I circled around again.

2016 saw plenty of good records, but this album had propulsion. The tracks were hot; they were fueled by the moment. But they also played on one another, building and deconstructing, creating a sound as cohesive and disparate as an immaculate jazz set. Across sixteen tracks, Tribe didn’t have much hope in the future, but they had hope in themselves — and that difference is distinct. It was a notion I’d lost sight of in the days before, that no matter where your country or your block or your economy or your boys or your neighborhood are headed, you yourself can be dope as shit. And you have the right to be whoever you are.

Eventually, the buildings beside me devolved into dirt roads and motels. I’d driven well into the middle of the nowhere when I finally stopped the record. The only appropriate reaction was silence. That palpable, physical feeling was back.

In June, Chris Jackson gave a speech for the Asian American Writer’s Workshop. As the editor-in-chief of Random House’s One World imprint, he’d arrived to accept an Editorial Achievement Award — and working my way through We got it from here…, his words rang in the back of my head:

It’s a big responsibility, holding a country as batshit crazy as this together, which is why we need to do it together. We — all of us across race and background who want to ally, who want to join together to create a wider, truer channel for our culture — are in a fight, which we should never forget. But we should also never forget how much we have already won.

Tribe works with a similar color palate, although their painting’s a shade darker. Across their larger oeuvre, the group stresses about imposters. They knock on the Knicks. They gripe about diabetes, relatives, and love interests. On one track, Phife is a two-time victim of car-theft before we even reach the hook. The narratives are original, but there’s a connective tissue between them, an undercurrent of wryness to reel every track home.

Instead of shying away from politics in lieu of braggadocio, they’ve placed them front and center on “We the People…”:

The OG Gucci boots are smitten with iguanas

The IRS piranha see a nigga gettin’ commas

Niggas in the hood living in a fishbowl

Gentrify here, now it’s not a shit hole

before literally mirroring the voice of that discrimination across the chorus:

All you Black folks, you must go

All you Mexicans, you must go

And all you poor folks, you must go

Muslims and gays, boy, we hate your ways

So all you bad folks, you must go

The riff, on “Ego”, about the burden of persevering in a society that could care less, and navigating a country that erases its dissonant voices:

Ego make you violent or govern like a tyrant

Or switch a dictionary’s word from vibrant to vivrant

Fool the thirsty people, selling tap water in bottles

Fooled a girl with NYU scholarship and now she models

Ego has no ending, has people pretending

Religious zealots get jealous ’cause guys want their defending

They do it all in jest. It is deathly serious play. Tribe acknowledges these realities, prodding and challenging them, and in “The Space Program,” come out laughing on the other side:

The danger must be growing

For the rowers keep on rowing

And they’re certainly not showing

Any signs that they are slowing!

“We’re there!”

“Where?”

“Here!”

A small step for mankind

But a giant step for us

Oompa, loompa, doopa dee doo

I’ve got another puzzle for you

Insofar as they’ve given us a political record, Tribe’s latest is also a victorious one. They know the oppressed can rise to occasion. They convey the unsayable thing, something we take for granted in rap today — that it’s sick to kill a cypher, as Phife notes on “The Donald”:

Recently on the internet they chatting

Taking polls, debating who could win in battle rapping

Let’s make it happen, these cyber flows already par

No subliminals, with me you know who the fuck you are

but acknowledging your mortality is even more radical. If it sounds contrived to laud rappers for consistently promoting self-awareness, it’s only because we’ve grown used to the precedent they’ve set.

Plenty of other acts drifted away from the culture of inter-genre beefing, redirecting the track space spent on fronting and hype towards slant rhymes, flipped rhythms, and blank verse behind the bass: De La Soul, Ultramagnetic MC’s, and The Pharcyde, among others. KRS-One, Rakim, and Nas found fan-bases through their stories and lyrical prowess — and their consistency was such that their personas, insofar as they had any, were built off of those skills alone. But Tribe further supplanted the culture of machismo with strategic sampling, placing less weight on coast identification than diversity of sound. They wore the craziest outfits in their videos, mixed anaphora with trailing hooks, and stuffed maracas into the chorus, because it made a dope track.

Tribe was to rap what Hendrix felt like to rock: interstellar. A little out of this world. And, ensconced in that coolness, and a mastery of their craft, this difference was heightened through their manipulation of even the most basic mechanics — they worked their choruses, segues, and transitions to the absolute limit. When those limits became apparent, they reworked them again.

Of course, Tribe had their issues (whose contours and conclusions were investigated thoroughly in Michael Rapaport’s lovely 2011 documentary, Beats, Rhymes, and Life: The Travels of A Tribe Called Quest). Near the end (or at least the first one) the group turned their aggression inward — they were good-to-go until they weren’t. They didn’t separate on the best terms. Their creative peculiarities, originally a hallmark, began to cement fissures. Egos dissolved. Old grievances reared their heads. It was a small price to pay considering everything they’d given.

“there were modern poets before there was modern poetry”

— Richard Ellman and Robert O’Clair, ‘The Norton Anthology of Modern Poetry’

To consider American music and its relation to hip-hop is to consider Tribe. In order to laud the youthful prowess of Chance, Noname, Vince Staples, and Anderson Paak; or to claim allegiance to Eminem, Andre 3000, The Roots, and J Dilla; or to stand in awe of Kendrick Lamar, our generation’s anointed innovator, is to stand in awe of Tribe. These artists’ ingenuity lies in their ability to pull from the world, to skate across tracks at the highest level, turning otherwise obscure references and allusions into essential additions — and who in hip-hop, to say nothing of American music full-stop, strove for multitudes as consistently? Because that’s what hip-hop is: constant redefinition of the self. The rhyme is born from the change, and Tribe’s only constant is their excellence.

So perhaps it comes as no surprise that when Q-Tip, after claiming in an interview with Billboard that “this is our last record… after that, that’s it for, the rest of our lives”, alluded to future plans to record on Annie Mac’s BBC Radio 1 show a few weeks later.

Stay tuned for any other incarnation, ’cause we don’t intend on stopping because that was Phife’s M.O. was, like, ‘This time we gotta do it and keep going,’ and now he’s left us with the equation of how do we do it, but we are going to need it, and we’re going to continue.

For most rappers, this indecision would be reductive. It could be perceived as played out, the lyricist’s kryptonite. But Tribe had done it before, turning these notions of insecurity and expectation on their heads, taking our preconceptions, obliterating them, and giving us their world. They were deliberately obtuse, before deliberate obtuseness became the standard. They were affectionate, in their own way, before emotionality was deemed acceptable, if not outright advantageous, on the record. And, through it all, they kept their feet on the ground. For most of us, slogging through the future will be a lot harder from here on out. But it isn’t, and can’t be, any less of a joy to try. And, ultimately, under Tribe’s watch, to triumph.