A Poem By Ange Mlinko

by Mark Bibbins, Editor

Lilies

“You can’t eat near me,” conceded the lilies.

“I turn even the wine in your mouth.

“The babouche of my anthers would paprika your tofu.

“I’m chrysanthemums’ antithesis.

“I am not the darling of Autumn.

“But hexa-petalled, I am the bad javelin of the future

come to you all unraveling.”

Ange Mlinko is the author of Shoulder Season (Coffee House Press). She lives and teaches in Houston.

Got a hankering for more poetry but not quite sure how to sate that urge? Head over here, to The Poetry Section’s vast archive. You may contact the editor at poems@theawl.com.

A Conversation With Novelist Helen DeWitt

A Conversation With Novelist Helen DeWitt

by Jenny Davidson

A friend of mine describes herself as a member of “the secret cult of the Samurai”: those who came across copies of Helen DeWitt’s novel The Last Samurai (2000) and fell in love with it and went on to buy countless copies to press into the hands of people they knew would feel the same way. I can’t even remember my first encounter with the book, it so immediately became a part of my interior landscape: The Last Samurai sits alongside Rebecca West’s The Fountain Overflows and James Baldwin’s Just Above My Head in my mental grouping of books that depict the simultaneous richness and dreadfulness of the lives of individuals in families (and in the world) in a rare fashion that speaks directly to my own subjective experience of such things.

Her new novel Lighting Rods (New Directions, 2011) was written before The Last Samurai was published, but has taken a roundabout path to publication. It’s an altogether different piece of writing: a sharp satirical fable that provides strong supporting evidence in favor of the proposition, as Marco Roth once put it to me, that DeWitt is 21st-century America’s best 18th-century novelist.

JENNY DAVIDSON: Here’s one sentence that caught my eye early on, as your protagonist Joe’s first trial of his sexual-release program for high-performing employees leads him to tweak the product he’s offering: “It meant another head-to-head with Beginning Programming for Dummies, but the thing that separates the sheep from the goats is the willingness to go that extra mile.”

This wild mixing of metaphors is wonderfully characteristic of a certain kind of management self-help book. (I remember watching an episode of “The Apprentice” once and being perplexed as to why all of the would-be apprentices so frequently used the expression “step up,” as in “step up to the plate” — would so-and-so “step up”? So-and-so really “stepped up” in that challenge.) Did you read any books of this ilk as you began working on Lightning Rods, and if so, which are your favorites?

HELEN DEWITT: I didn’t read any, as far as I can remember, when I was working on the book. I’d come across people who were salesmen, or were trying to be, over the years. I once knew a student from Yale who was working on Russian and Chinese, spent a summer in Provincetown as an Electrolux rep; I worked in the office of an Allstate insurance salesman for a while; my mother used to be a real estate agent…

The thing that struck me was that selling was always bound up with some kind of theory of human nature, with helping people to recognize and act on a gap between their conception of themselves and what they were actually doing. Or, sometimes, helping them to formulate a new conception of themselves which involved commitment to a product — a vacuum cleaner, life insurance, a house. With this went the seller’s image of his or her place in some larger system — so my mother, for instance, would comment that buying a house, for many people, was the single most important financial decision they would make, one that gave ordinary people a chance to acquire capital, one that was in effect a mechanism to enforce the discipline of savings. (I thought you were just buying a place to live.)

I would then find books on their shelves which were a mixture of motivational literature, sociology and practical advice (there would be scripts, scenes); the mixed metaphors you mention seemed to be flung out not because they were coherent, but because certain formulaic phrases, regardless of application, had a sort of Pavlovian effect. (“Touch base” came up a lot, often in a way that was wholly divorced from the original meaning of the term: “I was impressed by the number of bases he thought to touch,” as though a baseball player could go the extra mile by deciding to touch fourth, fifth, sixth and seventh bases, or maybe even an extra ten, rather than settling for the conventional three before unimaginatively heading for home.)

The novel’s title sounds quite abstract at first, but it turns out that though it’s a metaphor, it’s a quite literal metaphor, if you know what I’m saying: it’s absolutely central to the theme of the book (it describes the book!) in a way that is surprising and appealing. Joe is convinced that providing sexual release to high-performing male office workers will let them siphon off their hostility and “insulate their negative emotions, instead of directing their aggression and hostility at their colleagues.” Did you know this was the title early on, or was it a late discovery?

I think I knew that had to be the title as soon as he came up with the idea, so more or less immediately.

You and I both spent a good deal of time, in earlier years, working in a secretarial support capacity. What did you learn from those years of typing and temping?

All kinds of things that have turned out to be a severe handicap to me as a professional writer. If you have a job that requires a lot of typing you end up getting a lot of practice; your speed builds up over the years, to the point where you can type faster than you think (at least if you are working out something complicated). This is fine for the actual writing of a book, or taking notes from a text, or blogging, but it is not so good for dealing with people in the industry. The temptation is to do business by email, and in particular to address complex subjects by writing long, complex emails. (It SEEMS to make sense because then everything is in writing, and both parties can go back and confirm what was said.)

This works if the person you write to is also a competent typist, someone similarly maddened by the constraints of a Blackberry or cell phone, someone who prefers to dash off 1,000-word emails in ten minutes on a full keyboard, on a (at a minimum) laptop with full screen on which your 1,000-word emails can be read rapidly in big blocks of screen space. Someone who will naturally interpolate replies to a series of questions into the text, permitting you to do the same in response.

If you are dealing with someone who thinks it worth typing ‘tmrw’ rather than tomorrow, someone who writes (and reads) emails by Blackberry, someone who gets many emails in the course of a day, the flood of text is likely to drive them mad. It’s better with this sort of person to keep emails to the length of a Tweet and do most business by phone. I didn’t know.

Equally disastrously, if you work as a secretary you internalize a simple hierarchical picture of the business world. Your academic qualifications are irrelevant; what counts is the place you occupy in the hierarchy. Occupying this position, you perform various tasks upon request. You don’t argue; you don’t explain that the task would best be performed by the person who made the request; you don’t put the task aside and explain, if asked, that it does not need to be done for another couple of months; you don’t put the task aside and explain, if asked, that none of the other places you worked ever asked you to perform it and that you are simply doing what you did in all the other places you worked. No, you just carry out the task as soon as asked, and you try to do it right first time. And none of this is contingent on enthusiasm for the people, or the project, or the company; you’ve been brought in to do a job, you do the job.

You then imagine that as a writer you can step into a system with a similar hierarchy, only at a different place in the hierarchy. You are no longer providing support; you are now the principal, the client, the person for whom services are provided. So you expect to give instructions and have them carried out promptly without argument. You give instructions and they are not so much airily waved aside as ignored. Mysteriously, people are lavish with praise of your talent, the word ‘genius’ is used with gay abandon, but the mere fact that you are a genius does not mean that you can have a document photocopied, a working group list, a meeting with an agenda. You (well, I, at any rate) are then prey to baffled rage.

Another stylistic device I enjoyed was your use of the repeated speech tag “He said:” to structure a whole sequence of observations in which your protagonist lays out his plan to use women as “lightning rods,” to “provide contact of a sexual nature to selected members of the firm” in order to minimize sexual harassment elsewhere. I couldn’t think of where else I might have seen this done before: did you have other examples in mind, or is it something you came up with specifically for this book?

I don’t think I’d come across it anywhere. It seemed right for the book, where a crazy idea in Joe’s head is converted to something in the world through his ability to put sentences out in the world, sentences that persuade people to do things. I say I don’t think I’d come across it, but now various things come to mind: Plato’s Symposium, in which the contributions of speakers, bringing the argument forward, are lightly marked with neutral verbs of saying to remind one of the confrontation or interaction of speakers with different positions; Raymond Queneau’s Zazie dans le metro, where the pronouncements of the characters are marked for humorous effect by verbs of saying; of Tristram Shandy, where, how can I put it, the interpolation of verbs of saying (not, of course, only the neutral ‘said’) in a long disquisition, such as one by the narrator’s father on a hobbyhorse, underlines the preposterousness of the notions, the intricate chain of reasoning by which a preposterous conclusion is reached, and the investment of the speaker in persuading a listener to set aside prevalent but false beliefs. There may well be other precursors that I now forget (I’m in New York and my library is back in Berlin, so I can’t check).

The specificity of the sexual fantasies on which your protagonist bases his “hole-in-the-wall” sexual-delivery system reminded me a little bit of Nicholson Baker’s novel The Fermata, a book which impressed me very much when I read it years ago. Your account of your character’s thought processes, though, is written in an amazing deadpan third-person voice that’s quite close to Joe’s thoughts, that is tonally difficult to pin down but that certainly doesn’t encourage sympathetic participation in those fantasies, however charged they may be for Joe himself (I’m thinking especially of the early passage in which he considers the logistics of the football team whose cheerleaders provide sexual services through a hole in the wall between the two locker rooms). I was just rereading Robbe-Grillet’s Project for a Revolution in New York, which in some clear sense incorporates the descriptive obsessiveness of pornography in order to shake up the protocols of narrative realism. What’s your take, just between the two of us, on Joe’s fantasies? To what extent are they primarily configured in a satirical mode; what elements of fantasy predominate; and why the focus on logistics?

This might fall in the category of ‘Because she was born a long long time ago.’ When I was a child, when I was in my teens, pornography was something that came my way very rarely; maybe a book or two on the shelves of a friend of my grandparents, a magazine left in the pocket of a seat on an airplane. This was naturally fascinating. There would be stories in which the author had gone to enormous trouble to set up a complicated, implausible scenario, apparently because the payoff depended not simply on the fact of penetration, but on the combination of penetration and pretending to a third party that nothing was happening.

So I don’t know that they were configured in a satirical mode, exactly, but whatever it was that made them work seemed to depend on a narrative of some kind, one in which the requirement of pretending that nothing was happening required, in turn, the motivation of some kind of physical set-up in which concealment was possible. If the believability of pretense was at the heart of the fantasy, this would require a plausible means of concealment, which would seem to mean paying a certain amount of attention to logistics and so diversion from the primary focus of the activity. So Joe’s attention to logistics was, to begin with, forced on him by the logic of the fantasy, but as thought was given to how something could genuinely be made to work the logical next step would be to see that something that could genuinely be made to work need not be confined to a fantasy…

Another moment I especially enjoyed was Renée’s “list of things that most people get wrong,” which includes prohibitions like “Never wear fake coins or medals as buttons” and “Never wear self-covered buttons in man-made fibers.” Where on earth did you get these, and what’s your take on this sort of detail-orientation?

Well, it occurred to me at some point that the reason I hate shopping is that I often walk into a store and find myself rejecting every garment out of hand because each violates at least one of what turns out to be a very long list of principles.

Oh, Lord. Well, it occurred to me at some point that the reason I hate shopping is that I often walk into a store and find myself rejecting every garment out of hand because each violates at least one of what turns out to be a very long list of principles. I need a sweater; I leave the house telling myself I must not return without a sweater; I go to, say, Peek & Cloppenburg, a Berlin department store with sweaters as far as the eye can see, and they are all WRONG. I go to 10 or 12 other stores and am unable to find even one sweater that will do. (The result is not that I am well dressed; I go about most of the time looking like a Beckettian tramp.) I’m not sure where these principles came from; they are simply strongly felt preferences, often ones I become conscious of only on being confronted with an array of misguided garments. (I think this is probably one of those occasions where structuralism is our friend, though I don’t think I can whip out an analysis on the spot.) I think this level of attention to detail is often characteristic of strong work in all kinds of different fields (I’m now thinking offhand of a master class I once heard by Murray Perahia; of Edward Tufte’s work on information design…) — one might not want to allocate it to sweater acquisition.

One thing I love about this book is that though it’s clearly a satire, and many of the specific details are non-realist or not plausible in a real-world setting, there is also an absolute literal-mindedness to them that makes them somehow perversely come back round to being plausible after all. So as to say that Renée’s revelation that the chunk of time she spends with her backside presented to the hole in the wall through which a high-performing employee will penetrate her and find sexual release is perfectly suited to reading Proust’s A la recherche du temps perdu in the original: “On the one hand she wouldn’t be reading a lot at any one time, so she wouldn’t get discouraged. On the other hand, it was quite a long book, so by the time she finished she’d probably have enough money for Harvard Law School.”

This, of course, is an extremely sensible thought! The combination of precision and wild implausibility in passages like this one strikes me as highly reminiscent of Swift’s satires (A Modest Proposal would probably be the most obvious example to invoke). In a different sense, too, the novel’s strongly structurally reminiscent of Candide, with its twists and turns of fate and its impervious protagonist. Are the 18th-century satirists important to you as a writer, or would you say that this is merely a technical and structural coincidence?

I’m trying to work out how to put this. I’d always thought of Lightning Rods as influenced mainly by Aristophanes and Mel Brooks (a preposterous idea worked out to its logical conclusion); the voice of Joe came into my head at a time when I was very depressed, and it reminded me somehow of Springtime for Hitler.

But as soon as you bring up 18th-century satirists I think: Of course! Or rather, I think: Not just 18th-century satirists (though I love Swift, Pope, Voltaire, Diderot) — a whole procession of 18th-century writers flash through the mind, relevant not just to this book but to the many queueing up on my hard drive. (Hume, Adam Smith, Gibbon come to mind; Johnson and Boswell; Fielding, Sterne — but the list is so much longer it would be tedious to go on.) Perhaps the points of connection are: First, that it was a time of projectionists; a great many people tried both to criticize their own society and to determine what a better one might look like through the operation of reason. Hence singularly vulnerable to false reasoning (Joe invokes Thomas Jefferson to justify his project; we may think of the many ingenious notions of Sir Walter Shandy). Second, that it was a time when people had a highly developed sense of generic conventions, and of the mismatch between these and the lives to which they might be applied. Third, that there was a love of wit, of the pointed phrase. “Sir John was a sportsman, Lady Middleton a mother” — this may not, for all we know, have appeared in the 1796 precursor to Sense and Sensibility, but it is an 18th-century line, and unimprovable.

Jenny Davidson teaches in the Department of English and Comparative Literature at Columbia University and blogs at Light Reading. She has just finished a novel called The Magic Circle.

Happy 6015th Birthday, Planet Earth!

NOTHING brings me greater pleasure than WorldNetDaily’s email list. Today’s subject line: “Earth’s 6015th birthday this year!” It’s an important way to keep in touch with the Other America. (Maybe I’ll actually buy this book, too! After all? “This is one of the most important literary, historical and Christian works you’ll ever own, a treasure for any home library. It’s a must for your homeschool library.”)

Global Alert: Beware of Sassy Ladies in Airports with Hula Hoops

14 teams enter. Only one can win. It’s the Amazing Hoop Race! Oh yes, it is on: “Proceed to the nearest airport and take your hoops with you. At the airport, share the joy of hooping with others. Record a travelogue of all airport patrons that join you for an airport hooping session. Each person who hoops successfully with a member of your team is worth one point, although a pilot is worth 5 points and a flight attendant is worth 3.” So all of the world should be warned about being approached by hot ladies with hula hoops.

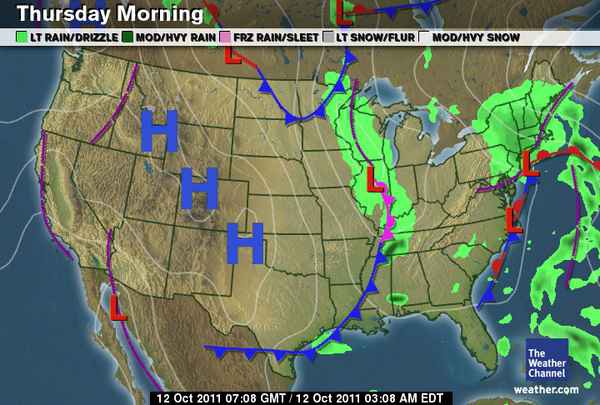

How To Read This Morning's Weather Map

Here’s this morning’s weather map, straight from the Weather Channel website. What do we see? Well, it’s going to be a purple line in California, typical for this time of year. Mountain West will see a lot of Hs — how nice for them! And the lumpy, blue-and-red line down the East Coast will stay for the remainder of the week into the weekend. Wait, what? Okay, so maybe when you look at a weather map you have a vague sense of what’s being indicated. Like, “hmm, those green clouds look ominous.” But how did they get there? And what’s going on with those other lines, letters and bumps?

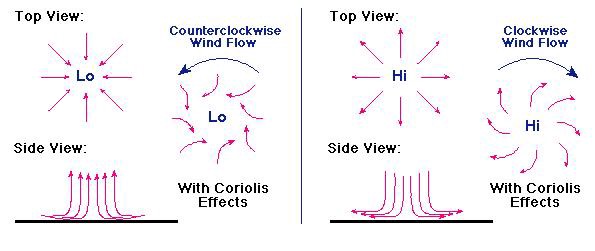

To understand what drives weather patterns, we need to first review the Coriolis Effect. It’ll be quick, I promise. Now: imagine yourself at the North Pole aiming for a target at the Equator. In this imaginary scenario you have a great arm and throw in a perfectly straight line. Give yourself a fancy hat too; why not? If this throw was on a stationary planet, you would hit the target. But you’re throwing on a constantly rotating planet and the target is constantly moving with the earth, you would miss the target even though the ball took a perfectly straight path. From the North Pole, your ball would appear to deflect to the right of the target. In reality, the target moved left with the earth’s rotation. That’s the Coriolis Effect, radically simplified, in action. Which is great if you need a science-y excuse for being terrible at catching things, but what does that mean for the weather?

Air masses are constantly moving from areas of high pressure (the Hs on the map) to low pressure (the Ls), but the rotation of the earth prevents the air from moving from H to L in a perfectly straight line. It deflects, like your ball, to the right. At the center of a low pressure system, air is rushing in from all directions. The rightward curve creates a spinning vortex of rising air, which is a lot less terrifying than it sounds. It happens, literally, all the time. Where there’s low pressure, there’s a spinning vortex of rising air. There’s one over Illinois as I write this and no one is panicking. Most people don’t realize there’s anything happening at all. Other than the rain, of course. Folks probably notice the rain.

It’s the low atmospheric pressure that allows air to rise. When air rises high enough it cools and the moisture present in the air condenses to form clouds. When the clouds are completely saturated, it rains. If there’s an L on the weather map closing in on your area, clouds and likely rain are headed your way. High pressure, on the other hand, means that the air is being forced downward — cloud formation is prevented. Sunny and clear days come with high pressure areas. That big H on the map is bringing clear weather to, for example, Colorado. It’s going to be pretty gorgeous in Denver this morning, and probably through the weekend. High pressure areas don’t move too fast.

All of this moving air, of course, creates wind. Air masses flow from areas of high pressure to areas of low pressure. The closer the pressure centers are to each other, the stronger the wind blows. Regrettably for our purposes but happily otherwise, there isn’t a great example of high winds on the lower 48 today. But you see those white lines? Those are isobars, and they connect points of equal barometric pressure. The closer together they are, the stronger the wind will blow there. Now let’s look at the areas not covered by giant letters. What’s going on with those bright, bumpy lines? Those are fronts. Fronts are masses of air with different temperatures and densities interacting with one another.

A warm front, symbolized on a weather map by a red line dotted with half circles, is a mass of warm air advancing upon a mass of cooler air. Warm fronts are slow moving, and somewhat short lived. When smooshed up next to another front, as is happening just south of New England, warm air rises above a mass of cooler air, giant clouds form and typically bring with them a lot of rain that clears quickly once the front has passed. (Here are a pair of basic animations of warm and cold fronts to help you visualize this.)

A cold front, symbolized on a weather map by a blue line strung with triangles is a mass of cooler air wedging itself beneath a mass of warm air. Cold fronts move faster and more forcefully than warm fronts. They are accompanied by dropping temperatures and sometimes, but not always, rain. Have you ever noticed how the air sometimes changes right before it rains? Things become more crisp and things just… smell different? That’s the cooler, drier air pushing the warmer, more humid air up and away (also, your sense of smell is stronger in high humidity, so you’re just smelling less, but that’s neither here nor there). The cold front moving across the Southeast right now is bringing light rain in some areas, but the air mass isn’t moist enough to cause heavy precipitation. They are, however, followed by the most delightful little cumulus clouds.

There is an occluded front, the bright purple line with both half circles and triangles, happening over the Kentucky/Indiana border. That means a cold front is overtaking a warm front: a mass of cooler air is passing under a mass of warm air trying to slide over a mass of cool air. Though it’s still too warm yet, occluded fronts are the type of air mass intermingling that brings thundersnow. Currently, though, just thunderstorms. And the other dark purple dashed lines? Those are troughs, elongated areas of low pressure. Not quite a spinning vortex, but capable of causing enough disturbance to warrant its own type of line on the map. In the Northern Hemisphere, air rises to the east of the line and sinks to the west. Thus, it is cloudier and rainier east of the line, and more settled west of it.

And finally, a stationary front, the red and blue line, lies just off the East Coast. This is when two air masses just don’t know what to do with each other as neither is strong enough to challenge the other. It is, as the name would suggest, not going anywhere anytime soon and will just dissipate on its own if neither air mass become strong enough to overtake the other. What does this mean on the ground? Clouds, mostly. If the air is already moist it will storm but it’s not as likely as a straightforward cold or warm front.

What can you take away from this, so that you can take a quick glance at a weather map and know what’s coming your way? If there’s a front approaching, really any kind of front, bring an umbrella. If the isolines are clustered, wear a jacket. If there’s a big H, remember your sunglasses; and if there’s a big L, you should probably put the white t shirt back in the closet and save it for a day when there isn’t any kind of symbol at all over your town.

Victoria Johnson is a cartographer and this is her Tumblr.

Weather map snagged from The Weather Channel. Coriolis chart courtesy of astrowiki.

"Work" Stopped in D.C. Thanks to the Great Eastern RIM Disaster

“It’s actually quite relaxing,” Philippe Reines, a State Department official and famously obsessive BlackBerry user, wrote from his desk. “You know you’re not missing anything because nobody else can send, either.”

— Sure it’s nice and quiet now, Philippe, but the D.C.-friendly BlackBerry is likely just a gateway drug. Wait till every lobbyist is barking commands at Siri.

Paul Simon Is 70

Even more disturbingly, Graceland is 25. The man’s talents are indisputable, his catalog impeccable, the idea of choosing one song to represent him impossible. But I’m gonna go with this one anyway. Happy birthday, Paul Simon!

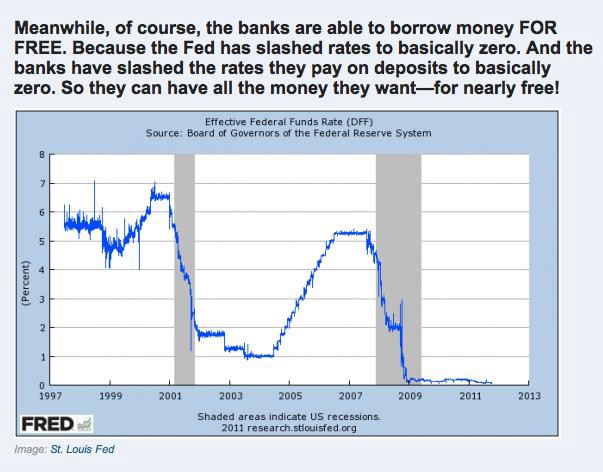

Your Ultimate Guide to Wealth Inequality and Banking Practices

Who woulda thunk that Business Insider, of all places, would provide an absolutely perfect and handy primer on the current state of banking and all the reasons you really should be marching on Jamie Dimon’s house? And yet here we are! It’s a wonderfully comprehensive and quite digestible little textbook on the real and astounding place we’ve found ourselves.

Occupy Wall Street's Big, Difficult Choice

Today would be a good day to take a pass on attending Occupy Wall Street’s “General Assembly” at 7 p.m. (although the 6 p.m. meeting on “Organizing Effectively Without Hierarchy” sounds cool and the 2 p.m. Structure Working Group meeting is a blessed thing). Because tonight, you’re going to find out who’s a cynic and who’s naive, and it’s going to get heated consensus-style, as the group addresses Mayor Bloomberg’s demand to come in and “clean up” Zuccotti Park, starting tomorrow. The park’s landlord’s letter to the NYPD, dated Tuesday, asking for help, is full of practical, liability-insurance-based complaints but also has plenty of nonsense, and it’s the “unsanitary and unsafe” claim appears to be resonating. So this is likely to escalate into a real and troubling confrontation; there’s almost no way Occupy Wall Street can give up the park — but protesters should know that the City doesn’t back down once it’s said it’s going to do something. (Photo from last night by Harrie van Veen.)

Why Should We Demonstrate? A Conversation

by Logan Sachon

Things I don’t understand about activism, the short list:

• Sleeping in a park if you have an actual bed somewhere to sleep in;

• Willingly being in a place where you increase your risk of being arrested/maced;

• Being uncomfortable in a crowd when you can just, you know, read coverage on blogs;

• How crowds of people with signs change anything, ever.

Amount I’m willing to concede ignorance on matters of activism:

• Oh, a lot;

• I’d go so far as to say “total.”

What I decided to do about it:

• Not take an eight-hour bus ride to New York City, that’s what;

• Get someone to explain it to me.

So I called up Sam Brody. He is a guy I went to college with, and the only person in my life who has done activist-type things on the regular. I know this because: he used to talk about these things (I obviously paid so much attention); he used to (and perhaps still does) wear t-shirts with political messages sharpied on them; and one time in 2002, Cary Tennis profiled him for Salon as a young anti-war activist. Sam is currently a PhD. student at the University of Chicago. He is a native New Yorker and was in Zucotti Park last Sunday. We had this conversation.

LOGAN SACHON: So, Sam. I have been watching the coverage for the past couple weeks —

SAM BRODY: Where have you been watching coverage?

LOGAN: I guess by watching, I don’t mean “watching.” I’ve been reading it. Mostly blogs. And what I’ve found is equal parts people saying, “This is awesome,” and people saying, “This is so unorganized, what is the point.” So what I’m interested in is: who is right? And more than that: how do protests work and what is the point of them?

SAM: Your general question — what is the purpose of street-based activism — is a good one.

The most recent thing that most people in our generation got excited about was the Obama campaign, from a liberal perspective. And that was a really clear goal: to elect one dude.

The most idealistic people maybe thought that electing this one dude would take care of a whole bunch of other things they cared about. And there were probably a lot of other people who weren’t that idealistic, but thought, well, electing this one dude won’t mean we won’t have to do all this other work, but it will be one good thing. There were a lot of people who got involved for the first time in politics on that campaign, and I think there were a lot of other folks who had been involved in activism for a long time who were kind of worried that if those people thought that the campaign didn’t deliver everything they wanted, they would just get kind of disillusioned with politics as a whole, and this kind of “plague on both their houses,” apathetic attitude that would emerge from that. That if the resulting Obama administration didn’t fix everything, you’d have people think, not in a political way, but in an attitudinal, existential way, that there’s no way to affect anything. And that you shouldn’t even bother trying.

And I think for a lot of people, that happened. They adopted this sort of very basic stance toward the world of, whoever runs things runs things, and it’s not me, and things are just going to keep being shitty, because some other people who have a lot of power and money are going to be the ones who decide what happens, basically.

I think there were a lot of folks who had been involved in activism for a long time who were kind of worried that if people thought that the campaign didn’t deliver everything they wanted, that if the resulting Obama administration didn’t fix everything, you’d have people think, not in a political way, but in an attitudinal, existential way, that there’s no way to affect anything. And that you shouldn’t even bother trying. And I think for a lot of people, that happened.

LOGAN: Unfortunately, I think I might be the poster child for this.

SAM: And so as a way of concluding a really long rambling answer to this question of “what is the point of street-based activism,” I think one of the main purposes in this case, and really the initial purpose, is to make a space, to open up a space, where people go and talk to other people about what they want to have happen.

Because maybe in your daily life you go to work, if you’re lucky enough to have a job, or maybe you go to a bar or some cultural event with your friends in the evening, and maybe politics is one thing that comes up at that or maybe it doesn’t. And you might have a stray thought here or there throughout the day about something if you happen to read the news, but when there’s a huge group of people that are all assembled in one place to talk about how something is seriously wrong and they want to do something about it, when you go there, that’s what you talk about. And you talk to a lot of different people and you hear a lot of different things, and if you start participating, it gives you sense of having power. And the more people realize that they’ve been missing that, the more people join up and ideally it has a snowball effect that does result in some change taking place, and ideally that’s the result of increased democratic involvement.

LOGAN: So it’s not necessarily the idea that media coverage of this event will make anyone that has any power change anything, but that it will inspire us to change stuff ourselves?

SAM: I mean, partially. Anything like this always has 500 million different goals and other things that it’s going to accomplish without even intending to accomplish them. So for example, one thing that I thought when I saw a reporter ask the President a question about Occupy Wall Street, and he used it as a chance to try to, he tried to say he agreed with the protesters, even though the reporter had framed the question as like, clearly they think you haven’t done enough and are part of the problem, like, just the fact that that interchange took place! Before Occupy Wall Street, the Tea Party were the loud people who were in the street doing things and making noise, which set a tone so that when reporters asked the President a question, they would say, “It seems like a lot of people out there think that government is too big and is spending a lot of money and that taxes are too high, what are you going to do about that?” Right? And now the question was from the opposite direction. And so simply having that be a thing that happens is important. And that didn’t even have anything to do with specific demands, which was the criticism that you hear. Like do they want Congress to reinstate Glass-Steagall? Do they want a transaction tax on financial transactions? And people can keep kind of asking these questions, and of course, that’s good, that since there’s a giant protest, they’re asking those questions about those policies and whether they are good ideas. So there are all kinds of possible outcomes.

The unions might actually have a political campaign in the works demanding something like a tax on financial transactions. If they did, they could use the protest to try to get that passed as legislation. But since it’s still inherently leaderless and not being run by the Democratic Party and not being run by any kind of union or activist group, it’s not going to go away just because some legislation gets passed either, which I think is another advantage of it. Because sometimes you have protests about single issues, like, we want to abolish the death penalty in this state, and if you win, well, then that’s great and you go home. But this is about something that is a much deeper problem and is very very complicated and has roots in all these different sectors of our political life, so it’s unlikely that it’s just going to go away anytime soon, and I think that’s really good.

LOGAN: So you were there for a day last week?

SAM: Yes, I went down this Sunday, actually.

LOGAN: My impression of you is that you grew up with activism, is that right?

SAM: I went to high school in New York City, which, you know, not too many conservatives at my school. But that doesn’t necessarily mean you’re going to do activist stuff. You can just have a bunch of liberals around who are just complaining about things. But it was the Giuliani years, and when they shot Amadou Diallo, he became a kind of representative figure. There was a lot of police brutality and instances of unarmed people getting killed by police back then, and there was a lot of high school presence at protests around that issue. And at the beginning of the year I was in Madison when they were occupying the Capitol in Madison, so I can compare Occupy Wall Street to that.

LOGAN: I’ve actually never been to a protest at all.

SAM: Oh really? [I think it would not be exaggerating to say that he said this with some shock.] Is it because you think they’re corny or you don’t get the point?

LOGAN: I think I’ve always felt like, that that is some people’s thing and I’m more subtle, or something. Like, some people protest, and I don’t do that.

SAM: When you say more subtle, is that like going to a protest makes you declare a stance that is possibly too absolute and maybe doesn’t accept nuances and stuff?

LOGAN: Not necessarily. I guess I mean, it’s more my style to have discussions with a few people rather than making a sign and going out there. I’ve just never done it. And part of it also is that I’ve always cared about what people think of me. And I’ve always felt, well, you really have to know your stuff to hit the streets. Like, yes. I’m decidedly pro-choice. But if you put a microphone in my face, I’m probably not going to be able to tell you why. You’ve got to give me a pen and paper and some time for me to craft that argument.

The March on Washington was just one event in a multi-decade-long movement of which everyone who was present had some experience organizing on the ground back wherever they came from, on a day-to-day basis, everyday. They didn’t all just say, “Let’s all have the March on Washington where Martin Luther King will say, I have a dream, and then black people will be equal!”

SAM: One thing that’s different about Occupy Wall Street, is that, oftentimes, a typical protest, if there’s such a thing, takes the form of a march or a rally. So the group organization calls the protest for a certain time and place on a particular day, and if it’s a march, they tell you where they start and where you end up and they get a permit from the police and they walk and carry their signs from where they start to where they end up. And if a lot of people show up it’ll get media attention (or if it’s the Tea Party, ten of them will show up and it will get media attention), and the goal of it is to publicly manifest a particular view or dissatisfaction about something and have that enter into people’s conversations. If it’s a rally, the whole thing will take place in one place, and there will be a stage or platform that everybody looks at, and somebody will make speeches, and maybe someone will come in between and play some music and sing a song. And that’s a very typical format, and there have always been people who are dissatisfied with that, because it can leave you in the end with a certain sense of, what was that for? Although everyone knows really famous instances like, the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom. But the March on Washington was just one event in a multi-decade-long movement of which everyone who was present had some experience organizing on the ground back wherever they came from, on a day-to-day basis, everyday. They didn’t all just say, “Let’s all have the March on Washington where Martin Luther King will say, I have a dream, and then black people will be equal!” It was just one part. It was a manifestation of the power of something that was already happening.

What was different about this was that it wasn’t a march and it wasn’t a rally, although they are having those things associated with it, but it’s an occupation, which really does seem to just be about creating a space. A lot of people I know who went, before they had been reading all these stories about the bailouts or income inequality or how much many more times a CEO makes than an average worker in the U.S. compared to other industrial countries or other things that they’d be complaining about, they might say, “Where is the outrage? Why aren’t people in the streets yelling?” And then when people do go in the streets, they’re like, “What are they doing there? What do they think is going to happen?”

But for some people, just seeing it there, it’s like, there it is, I can go there, and people there will share something with me, even if I don’t know what it is or I can’t put my finger on it. The longer the occupation lasts, the more people from different backgrounds and different perspectives will be able to come and share those views with the people there. The basically hardcore group who are actually occupying becomes this opening for all these other people, people who have jobs, people who can’t live in the street, people who are interested in pursuing political channels for their problems to go and interface and connect with the broad possible spectrum of people that are interested in achieving the same kinds of things that they are.

LOGAN: So when you were there, did it feel good?

It’s a public space literally being taken over for chaotic public discussion, so you can’t say, only people that can pass through all my filters of aesthetic and political criteria can be there.

SAM: Well, I am a hyper-critical personality, so in that way I’m sort of like a typical media person. When I go down there, my eyes are drawn to the most extreme crackpot or hippie looking people. So there was some dude standing there with a sign, and he was like “NAZI BANKERS,” and I was like, oh, g-d. And his sign was the biggest, it was bigger than his entire body and he was holding it with his arms stretched out. And you knew that guy was going to be in every picture, and some people had gone up and talked to him and he was apparently impervious to people saying, like, “Dude, Nazi comparisons make you lose.” But in the past, it would have been like, I don’t want to stand in any group of people that that guy is in, but you literally can’t control it. It’s a public space literally being taken over for chaotic public discussion, so you can’t say, only people that can pass through all my filters of aesthetic and political criteria can be there.

So once you get over that fear of being associated with people that don’t take baths or people that say Hitler all the time, you just sort of find the people that you do need to be talking to.

LOGAN: So when you went to Madison, where did you sleep?

SAM: I only slept in the Capitol a couple of the nights, and the rest of the time I crashed with this guy Trevor who was generous enough to offer me a spot at his place. But almost everyone I met offered to let me crash at their place. The second I walked in there, everyone was like, oh wow, you came here from Chicago? Oh wow, thanks for coming, do you need somewhere to stay? So I had my pick of places to stay. But in the Capitol I just kind of slept on the floor in the hallway.

But the Wall Street one, too, they have a meal section, there’s a central table with all this food on it, and people are constantly coming and dropping off food, and that’s what I did. I dropped off food because I didn’t want to feel like I was just a protest tourist, so I brought and dropped off some food so at least I would feel like I had done something. But then behind the food table you have all these people washing dishes in tubs of soapy water and then to the right of that there is a table with all this medicine and first aid stuff on them. And there are people who put red tape on themselves, and they’re medics. Like, how do you know they’re medics? You don’t have the opportunity to interview these people and find out what makes them medics, but you just trust that if you get pepper sprayed or something, they will know what they’re doing. And then there’s a really long thing that’s like a People’s Library, and it was just a bunch of books. Take one! Bring one! So there’s all these things that just kind of spring up, and no one tells anyone that they have to do these things, they just kind of know and do it. And that energy is what makes it feel like an alternate place. People are in charge of their own shit here. And that greatly contributes to the sense of empowerment.

LOGAN: Was it hard for you to leave? Do you find yourself wishing you were there?

SAM: My friend Tasha had that feeling. She says she felt like everyday when she left there she was going to a worse place, that she was going to a mean place where people were not open and not understanding and judgmental. And so she’s actually been going back everyday. And I kind of wish I was there, but I’m in Chicago doing what I’m doing. But now they’ve started one in Chicago, so I’m probably going to go down there one day this week and see what’s going on.

LOGAN: Have you looked at the we are the 99 percent Tumblr?

SAM: Yeah, it’s depressing isn’t it?

LOGAN: It’s totally depressing. It gives me chest pains.

SAM: I know some people who are like, I don’t know what the people on Wall Street are about, but that Tumblr is killer. And well, that is what it’s about. I guess, nobody really has a concrete notion of how any particular action could address all of those people’s problems. So, everyone understands someone’s individual story of hardship and suffering, but to connect that up to the systematic reasons that are the same reasons that caused someone else’s story of hardship and suffering is more difficult.

But a lot of people are perfectly capable of hearing those stories and blaming them on something completely different. Like people with conservative politics, for example, might read that blog and think, this is because the government spends too much money and doesn’t allow job creators to create jobs and that’s why these people have no jobs. And I think that’s ridiculous and stupid, but you don’t have to be irrational to believe that. I think it’s good that there is a loud and visible presence that doesn’t think that’s the explanation, because when it was only the Tea Party, I think we were in real trouble.

LOGAN: Yes, and I feel that most of my life, at least the part when I’ve been aware of politics, it’s been very much that the vocal conservatives are out there making a fuss, and the liberals are at home, watching the Daily Show and rolling their eyes.

You have to be really sincere and really zealous, and not basically complacent or comfortable, to think that going and setting up camp in some park near Wall Street is going to affect what anyone thinks about anything.

SAM: I think that there’s also, a certain cultural pessimism or cynicism even that goes with the cultural cachet that irony has among a certain class of liberal people, and I say that because it’s certainly not universal to all races and classes of liberal people, but there’s a certain attitude among the people that I know, that, when you talk about the sixties and you talk about hippies and stuff, you sort of laugh, because they were so earnest and they just talked about loving everybody, and seriously? Were they kidding or what. And I think at a certain point, that attitude becomes debilitating. You can express an ironic or critical comment that you think is in line with what other people you’re talking to are saying, but if you say something that is super sincere and also not something that is immediately obvious, you expect some kind of backlash. The sincerity of people who really believe that they can change things is just like, too much. Because like everyone who knows anything knows that you can’t really. And that’s part of the reason that movements like Occupy Wall Street get started by anarchists, and not by smart well-educated liberals who come out of college and go into non-profit organizing. I mean, you have to be really sincere and really zealous, and not basically complacent or comfortable, to think that going and setting up camp in some park near Wall Street is going to affect what anyone thinks about anything. And you can’t be worried that it might not be cool to believe in something.

LOGAN: So, should we all be heading down to the park?

SAM: Yeah. But if you have a job, obviously, you have to go to your job, because that’s what’s important, and you have to be able to get money, especially if you have a family. But if you don’t have a job, or you’re kind of flexible like me because you’re a student, that’s why students always run these things. It’s not just because they’re young and idealistic; it’s because they’re able. They literally have the time.

So that’s why the model seems to be, you have some people who are always there, and you have special days that get called for mass protests and rallies which happen either after work hours or on weekends so that everyone else can come. And eventually you can have things like strikes, and people can walk out of work in order to show solidarity with something. And a strike is something that has real power to stop the ordinary operation of society. In terms of non-violent social change, a strike on the part of the union is one of the only proven things that can achieve powerful change. A general strike is the most powerful non-violent tool of social change that exists, but we can’t even have a general strike, because we don’t have a enough workers in unions and general strikes are illegal.

LOGAN: What does a general strike mean?

SAM: So typically, a strike happens if a union is negotiating with management about wages or benefits or whatever they are negotiating about, they have the option to strike in support of their position. And management can hire non-union workers to try to take their place in the meantime, but if people are not willing to break the strike by getting hired, then management can be forced to capitulate to the strike. There are industry-wide strikes, which is if one airline pilot union is negotiating with their airline then the rest of the airline pilots can go on strike with them, because it helps all the airline pilots for one airline’s pilots to get paid more. A general strike is across industries. So if the railway workers were striking 100 years ago, the dock workers would go strike, too, even though they had nothing to do with the railways. So when the labor movement was at its strongest, something like that could just stop the economy, and management would be much more likely to do what the unions wanted. And the reason organized labor is so weak now is because conscious policies were put in place that made it impossible to have general strikes and made it harder for individual workers at different workplaces to join unions. So the more that stuff like this is able to happen, it’s possible that it could help or contribute to the growth of organized labor, which could contribute to the increase of more tactics for putting extreme pressure on quote unquote, the one percent, or whatever.

LOGAN: How do you think this might play out?

SAM: That’s a really good question. Anything, literally anything, anything can happen. There’s a chance that some moderate reforms might get passed, but right now Congress seems to be completely unable or unwilling to do anything, literally anything. It is a non-functioning institution, practically. And so it’s difficult to imagine change along those lines until after the next election, maybe.

But once something seizes the public imagination, stuff can happen way faster than you would expect or completely unanticipated things can change everybody’s perception of the situation. So I think what it has the functionality to be is a catalyst for changes we can’t even imagine right now. And that’s another reason that I’m glad that they aren’t simply making a list of demands for the people in power, like hey, do this for us. Because then everything would just dissolve into a debate of whether or not those particular things should happen. And what it is instead of that is a very broad and wide-ranging conversation about the organization of our society, what our priorities are, how we operate in very deep and fundamental ways. And that is basically an increase of democratization, and I think the more democratic with a small “d” our public discourse gets, the more unpredictable what’s going to happen is, and I think that’s good.

Logan Sachon is thinking about it.

Photograph from Occupy Wall Street by K. Kendall.