'Homeland' And 'Enlightened': Women On The Verge Of Nervous Breakthroughs

by Michelle Dean

Mention Lindsay Lohan to me and you’ll be treated to an excoriation of the joy with which this culture greets your average female public breakdown. As such, I’ve surprised myself this fall with my absorption in the personal and professional unravellings of two female television characters: Carrie Mathison of “Homeland” (Claire Danes) and Amy Jellicoe of “Enlightened” (Laura Dern). If you’ve also been watching those shows, you might question my yoking them together. Carrie and Amy could not occupy (heh) two more different dramatic universes. “Homeland” is a taut, quickly paced thriller about terrorism whose signature gesture is to end each episode on the edge of a cliff; while “Enlightened” is a more meditative, patient, voiced-over and incredibly intelligent dramatization of a sort of Eat, Pray, Love moment in the life of one not-particularly-remarkable woman in California.

All the same, I think of both their lead characters, Carrie and Amy, as a pair. Both are struggling with the place of work in their lives; neither is particularly adept at maintaining healthy romantic relationships. Both are also suffering from mental illness, although Carrie’s is identifiable as bipolar disorder, whereas Amy seems to suffer from a more diffuse sort of ailment on the anxiety/depression spectrum. In their twin sufferings they have become talismans for me in a way that no more overtly politicized depiction of ladies on television has ever quite done — not Peggy of “Mad Men” nor, and this pains me to admit it, even Buffy. They’re articulating something new about vulnerability in women that I haven’t seen said before, at least not in precisely this way, on television. And I, for one, am hooked.

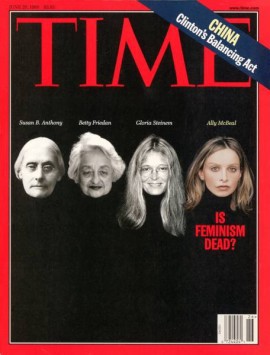

I use the word “vulnerability” advisedly here. I’m old enough to recall the fall of the Berlin Wall as an interruption of a rerun of “Growing Pains” (or was it “Who’s the Boss?”). Those of you who share that description probably also remember that charming interlude in our TV-watching lives where we were invited to contemplate “Ally McBeal” as at once an icon and Grim Reaper of female liberation. Time got in on that game with typical subtlety and thoughtfulness by running a cover image of the disembodied heads of Susan B. Anthony, Betty Friedan and Gloria Steinem floating in a black void alongside Ally’s and the question, “Is Feminism Dead?”

The particulars of the accompanying essay, penned by (oh brother) Ginia Bellafante, are not worth rehashing. For one thing, it’s about a show that is now largely and rightfully forgotten. (Though I do sometimes wonder whatever happened to that piano lady.) For another, the essay itself is pretty bad. (In Bellafante’s eyes, Katie Roiphe’s greatest sin up to then was appearing in a Coach ad.) And these arguments always take the same utterly depressing tack: step out of line, make a mistake, enjoy cute babies, feel badly, cry at work, be, in other words, wounded and imperfect, and your failings are judged not just as your own, but as those of the entire sisterhood, q.e.d.

Most shows about women have, perhaps unintentionally, made themselves susceptible to this boring, repetitive debate because they simply cannot stop announcing at every available opportunity that they are Television Shows About Women, Goddamnit. (Let’s call them TSAWGs.) Whether you want to blame TSAWG creators or network-driven marketing campaigns is immaterial — the fact is that we are meant to see Ally and Buffy and, even to a certain extent, Peggy as leading archetypal female lives, so when they are weak and/or strong and/or prone to cute outfits, we are invited to see “women” as being the same way. This sets a trap for the critic who, while believing in equality, wants her art to be something other than a position paper, as I can say from experience. For your reviews, you then have to work out how to simultaneously applaud any dramatic interest in women’s lives — it being rare enough to begin with — while registering any reservations you may have that such a pat thing as “women’s lives” exists. Look. Of course I’ve known Allys and Buffys and Peggys, but I’ve known a hundred other kinds of women too, not all of them middle class and/or white. (I know!) The idea that we share, as women, necessarily common interiorities — rather than common treatment from the world outside our tiny, skull-sized kingdoms — well, it is, and always has been, to put it politely, utter bunk. Flightiness and envy and shame — male, female, whatever, we all have to deal with those emotions. (Go into any bar and you’ll find as much emotional need at a table of male investment bankers as you will at the girls’ night out a few feet away; there’s not as much distance between “you go, girl” and Hugo-Bossed chest-beating as most would like to think.)

Anyway, my point is this: it’s important that neither “Homeland” nor “Enlightened” have arrived at the parade bearing that About Women banner. Their female leads don’t have to hold up any feminist or post-feminist placards. (Are we at post-post-feminist, pop-culturally speaking, yet? I keep losing track.) Without that freight, the shows can stumble on to obvious-and-yet-not-obvious insights that TSAWGs have traditionally resisted depicting, and to boot get to do so without having to claim for their (also white and middle class) heroines anything other than their own individuality.

Take, for example, the most egregious mistake the otherwise competent and ambitious CIA agent Carrie has made in this inaugural season of “Homeland”: when she crosses the line and sleeps with Brody, the ex-POW target she’s investigating. The choice is (at least initially) presented to us as one outside of traditional TSAWG protocol when Our Heroine sleeps with Our (Anti)hero. What Carrie does is heedless and impulsive, to be sure, but her choice to do it isn’t about lunar cycles or Women In Love or even, in a gesture favoured by analogous TSAWGs like “Alias” and “Damages,” an attempt to avenge some perfect idealized man assassinated in a bathtub at the outset of the series. It simply comes out of nowhere, as much bad-idea sex does. (Or so I’ve, uh, heard.)

Carrie later tells Brody that she originally slept with him to trick him into confessing that he’d been “turned” as a POW in Iraq. But a more recent admission to her mentor Saul, of her fear that she will always be “alone,” suggests a more traditional explanation. Perhaps the answer is both, which would be something quite a bit more like real life, wouldn’t it, than an either/or diagnosis. Admittedly, it’s often hard to say, in “Homeland,” which ambiguities are intentional. The creators are veterans of “24,” not a show that evinced a sophisticated understanding of human psychology and thus it’s likely that ulterior motives are here as plot devices rather than as tools to deepen character. Whatever the case, Angela Chase Danes manages to take the chaotic writing and unify Carrie into a difficult, loud, excessively blunt mess of a person. It’s not so much that she makes Carrie sympathetic as she makes her recognizable.

In that sense Amy, as played by Laura Dern, is Carrie’s polar opposite, far easier to like in her own cringeworthy way. Admittedly, the topology of Mike White’s “Enlightened” is more familiarly TSAWG-ish. Amy’s vulnerability stems from what seems like the usual suspects of TSAWG breakdowns: a difficult mother, a miscarriage, the (at least partially) consequent breakdown of a marriage, a workplace affair. The potential for the feminine cliché seemed, as I watched those first few episodes, very high. But then I changed my mind. [In “Enlightened,” these problems are not presented to us as “female” — though Amy does occasionally harbor certain ambitions for sisterhood at Abbadonn, the company where she works — but rather as existential. This shift of frame is subtle but important. Amy gets to lay claim to questions about meaning and loss and love in terms that are so abstract as to be universal and yet that don’t simply capitulate to the (old/white/male) terms of traditional philosophy.

For those of you not yet watching, such an ethos may make “Enlightened” sound fatally pretentious and vague. And it could be — but it isn’t. Somehow White’s writing manages to straddle the ridiculous and the touching in utterly unmanipulative ways. Here is the scene I’d use to make my pitch to you to start watching: In the fourth episode, Amy goes on a rafting trip with her ex-husband, one that she clearly hopes will renew the bond they once felt. It ends instead with him getting high and confused and fulfilling every cliché of the deadbeat ex-husband you can imagine. He loves Amy, it’s clear, but the situation is nonetheless hopeless. And Amy, well, her reaction is neither to run out and buy tissues nor to declare herself “done with men.” Instead, she just ruminates:

You can try to escape the story of your life but you can’t, it happened, the baby died, the dog died, the heart broke, I knew you when you were young, I know your heart broke, too. I will know you when we are both old and maybe wise, I hope wise. I know you now. Your story. Mine isn’t the one I would have chosen in the beginning but I’ll take it. It is my story. It’s only mine. And it’s not over. There’s time. There is time. There is so much time…

Amy delivers this speech while standing in a rose garden on a wide and sunny day. There is no walk home in the rain, with the strums of a strong woman’s ballad playing underneath. Nor some vow of renewal and a triumphant martini with three girlfriends, (as we traveling foursomes of women are wont to enjoy). Shedding these cliches, Amy’s Zenlike rejection of hysterical, cuticle-and-life-destroying anxiety about whether she should marry or settle or have kids or freeze her eggs or opt out or keep working or stop being such a goddamned rare spotted owl — well, for the love of Christ, it’s so downright refreshing, even revolutionary, to see these questions thought about in less all/nothing, either/or, fearmongering terms.

Should this trend catch on, of course, some people inevitably may be disappointed — the producers of reductive and silly magazine covers, for example, who won’t be able to wring the same sensationalism from “What Me, Marry?” and “Marry Him!” — but I think we could probably learn to carry on anyway.

Related: Laura Dern Is Our Only Hope For Bringing David Lynch Back

Michelle Dean writes in a lot of places, now. Follow her onTwitter

This Is A Very Special Video

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Nhq1uWY9wHg

You’ll need to stick with this one until about the 2:20 mark. After that you’re free to do whatever you’d like, but my guess is you’ll hang around, ensorcelled by its magical somethingness. Ladies and gentlemen, “The King That Never Was.” [Via]

See You Tonight For Our Holiday Party?

It’s tonight. The Holiday Awl Bawl. At Flaming Saddles. Which is 793 9th Avenue, 6 to 9 p.m. NEW YORK CITY. There will be nametags with tiny Awls on them. You will definitely meet great people with whom to have sexual intercourse. Be there or be dead inside. Oh and: This extremely gay bar is cash-only. As one does.

'Satyagraha' and Occupy Lincoln Center, Last Night

by Seth Colter Walls

The biggest opera house in the United States concluded its performance on time last night, at 11:15 p.m. Many of the nearly 4,000 people in attendance at the Met lingered in their seats for a bit, the better to praise the cast, orchestra and conductor — as well as to see if Philip Glass would take a curtain call. A number would have heard that the composer of Satyagraha, an opera about the life (sorta) and philosophical lineage (more consequentially) of Gandhi, was meant to have already spoken, at 10:30 p.m., to the Occupy Lincoln Center group just outside. When Glass did at last appear on stage, he was met with a rowdy harmony of cheers from what sounded like all levels of the opera house. Seeing a living composer take a bow in person after some masterful interpretation of his or her work can often carry a charge. But this time, the aggregate cheer’s decibel-level felt augmented as well by the collision of the piece in question, first performed in 1980, and the specific time and place of its present revival. Police-evicted Occupy Wall Street protesters could be seen from the windows of the balcony-level’s intermission space as patrons departed.

Satyagraha, or (loosely) “truth force” in Sanskrit, is all about a certain form of commitment not at all foreign to social justice movements in general, the Occupy project included. Its first act evokes the real-life exchange of letters and inspiration between Leo Tolstoy (around the period of his anarcho-mystically Christian late novel Resurrection, which is unjustly neglected) and the young lawyer Gandhi. Act Two posits the intellectual Tagore as precursor to Gandhi’s journalistic work with Indian Opinion. Act Three passes the passive resistance torch on to Martin Luther King, Jr.

In the Met’s production, by Phelim McDermott, the American Civil Rights movement plays out in chiaroscuro fashion, at the back of the stage for a long portion of the final act; King rises to a podium while Gandhi combats the “color bar” laws of the government in the foreground. At one juncture, the shadows of acrobats who are miming, in slow motion, the violence of police against Civil Rights protestors are visible through windows scrimmed with newspapers. Meantime, projections of documentary videos showing similar truth-forces play around the borders of those same windows. When the shock troops break the historical fourth wall, slicing the newspapers into ribbons as they move from the deep American south into the forward-stage world of Gandhi’s compatriots, the viewer’s response may be to object on the basis of some temporal-spacial order. Police can’t just do that, can they? They can’t magically cross continents and decades in order to tamp down any social movement they choose, right?

The constricts that power itself is obliged to observe are actually amorphous, at least from the outside; it’s hard to know exactly where they really lie, or when, or to what degree, they may ever be changing. This accounts not just for what we may now commonly describe as Kafkaesque machinations of legal systems, but also citizens’ wariness regarding nascent social movements. (Are they “really” doing something important? Are they “good” at whatever it is? Are they “likely” to succeed regarding issues “coherently” expressed?)

This is all part of power’s language. So, on Thursday night, were phrases like: “Exit down the ramp to the right,” which is what opera-goers heard from police trying to keep the Occupy movement cleanly separate from the people who had just watched Satyagraha. The blitheness with which these official police suggestions were ignored, or even taken as “suggestions,” was striking. So too, given the very recent history in Zuccotti Park, was the total lack of consequence suffered by those disobeying these directions. Wearing a suit — even a cheap one — has its privileges.

A few opera-goers assisted the front line of Occupy protesters in opening up a split between two barricades. A cop, hearing the unclanking kiss of the metal hooks, looked on somewhat confusedly as protestors elected not to simply swarm into the plaza. “This is dumb,” a young man told the cop. “We don’t need these separating us.” Then a couple reinforcements came to the solitary cop’s aide; before long the integrity of the barricade was restored.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=MUXI3O8SAaQ

[Video of Glass taken by Alex Ross]

Philip Glass had already come and gone — having recited a brief excerpt from Act III of Satyagraha — before ticket-holders descending from balcony level at the Met could reach the Occupy group. If at first it seemed depressing to realize that one could not attend both “events” on the same evening, the crowd did its best to erase that inside/outside distinction by repeating Glass’s excerpt several times, in the by-now well-storied “mic check” fashion, with waves of sound fanning out over the expanse of Lincoln Center Plaza. To occupy with a physical presence is only one method. Sound can occupy, too. “Thank you to the people on the other side of the fence for joining us,” the crowd said, as the Occupation roughly doubled in size after a period of steady accretion on the other side of the police-patrolled fence.

Then many opera-goers simply jumped the barricade. Lou Reed and Laurie Anderson, seen earlier at the orchestra-level of the Met, took the long way around and joined the right flank of the group. Quickly recognized, they then began a very cute, older-couple’s conversation about whether to accept an invitation to be “wedged” toward the center and placed “on stack” to speak.

“I don’t feel comfortable being ‘the guy,’ but I’ll say something if it’ll help things,” Reed said.

“We could say we support the 99% one-hundred percent,” Anderson suggested.

A tall man in a black hoodie helped lead Reed and Anderson deeper into the crowd. Give the celebrity couple points for patience; it took almost an hour for them to be heard, on one of the first for-real wintry nights in New York so far this season. Anderson spoke first, not long after a young man who said he’d been arrested at Zuccotti and thought cops generally “horrid.” She took a different (if familiar) tack, saying that police were properly part of an ideal movement (“our colleagues and our friends”). She also asked the crowd to think of ways to talk to those “who are not necessarily your friends” about the Occupy movement.

When Reed spoke, he seemed both angrier about the barricades (“I’ve never been more ashamed,” he said, to be a Brooklyn-born artist), as well as more conditional in his affection for the police. “The police are our army,” he said, in a subtle rebuke to Mayor Bloomberg’s claims of ownership, before saying “I want to be friends” with the cops — as though it were up to them to earn that friendship.

Several of the non-famous speakers were even better. One older man, who sported a thick, Eastern Europe-sounding accent, made a useful point about the act of imposition suggested by an occupation. Arguing that the truth-force of nonviolent protest “starts in the street and moves into the artistic and intellectual space,” he suggested a common cause between the Occupy group and Satyagraha as an opera. In this account, it was the police who were occupying a space unjustly, by keeping the two apart. “So we demand that the police occupation of our artistic space be ended immediately,” he concluded.

More than a few speakers seemed to want to claim the mantle of Satyagraha’s generally agreed-to awesomeness for themselves while decrying a contemporary classical music establishment from positions of frankly obvious ignorance. “Opera is expensive…. Only wealthy people can experience this wonderful artform,” one young woman sighed, as though crushed by her failed but honest attempts to do so.

It bears repeating: at the Met, the most expensive opera tickets are indeed expensive, but you can stand behind the orchestra section — or even sit at the upper reaches of the house — for less than the cost of an IMAX showing at the AMC Loews Lincoln Square 13 multiplex up the road. This persistent fiction of “elitism,” and contemporary classical music’s supposed inaccessibility, is one of the strongest propagandistic tools ever devised by the titans of corporate pop culture. They would prefer you not ever cost-compare a Family Circle seat to Satyagraha alongisde a 3D screening of Transformers 3.

Resentment directed toward a class of experience whose accessibility remains a matter of loose suppression is, in turn, the tool of social conservatives who hate public arts funding as much as they dig budget-busting tax cuts for the rich. Were we to realize a more progressive tax code, America might even be able to establish a public arts infrastructure that could more easily do without the ego-boosting contributions from the likes of the Koch family. In the meantime, we can take a page from Adbusters’ “every dollar spent is a vote” ethos and decide what do with the $20 bills that we do control. Among the populist moves the Met has made in recent years is its “Live in HD” program, beamed to movie theaters in areas of the country that may not have so many top-flight opera houses currently operating. Though apt to pursue safe programming bets that sate the desire of traditional opera fans, the Met’s administration places the occasional bet on a piece of radical culture like Satyagraha, which played in movie theaters on November 19th. That broadcast will have an encore next Wednesday, December 7th. It’s a good time to be reminded that not all forms of cultural occupation necessitate standing out in the cold.

Seth Colter Walls is a culture critic and reporter for Slate, the Village Voice, the Washington Post, Capital New York, and also a contributing writer to XXL Magazine. Photos and video by Brian Perkins.

Do You Smell Nervous?

SNIFF MY DOMINANCE: “Getting to know someone usually requires at least a little conversation. But a new study suggests you can get a hint of an individual’s personality through his or her scent alone. Participants in the study assessed, with some degree of accuracy, how outgoing, anxious or dominant people were after only taking a whiff of their clothes. The study is the first to test whether personality traits can be discerned through body odor.”

Wine Will Soothe The Pain

An upside to the potential collapse of the single European currency: cheaper wine! The downside is a worldwide financial crisis, but it probably won’t hurt so much if you’re drunk on a fine, newly-affordable Italian red. [Via]

Hopeless, Racist Wasps

“Individually, each wasp flew from the bottom of the T to the fork, where they could view an image on either side before picking one to touch. One of the two images delivered a mild and unpleasant shock. For each pair of images, wasps had 40 chances to learn which was a safer bet. When wasps were shown two distinct wasp faces, it only took about 10 trials before they learned to consistently choose the right one, the researchers report today in the journal Science. For the next 30 trials, they picked right about 75 to 80 percent of the time. The insects were eventually able to perform as well when shown two different black shapes on a white background, but it took them a lot longer. It wasn’t until close to the end of 40 trials that they were scoring right with the same success rate. When asked to distinguish between caterpillars, the wasps were hopeless.”

— What a surprise. To wasps, all caterpillars look the same. Besides explaining everything about the history of America and the Ivy League, this study, conducted at the University of Michigan’s evolutionary biology department, indicates that the “need to distinguish between faces has driven the evolution” of species that have been on the planet much longer than mammals and humans.

Live Long Enough And You Will See A Tribute Album To Everything

I am keeping a skeptical-yet-hopeful eye out on this.

Hollywood Insider Reveals Meaning Of Industry Jargon

“In showbiz, there is the term ‘jumping the shark’ that is used to describe a project in decline. It is derived from the hit sit-com ‘Happy Days’ which, sorely lacking for material after years on the air, featured a show wherein The Fonz went waterskiing in a leather jacket and encountered a shark. You guessed it: the Fonz jumped over the shark on the skis. After that, the days were not so happy on that program.”

— Noted cultural arbiter Bill O’Reilly has concerns about Lady Gaga’s career. As, I suppose, do we all.