This Old House

A portrait of light reno

Today, New York Times correspondents Glenn Thrush and Maggie Haberman ran a piece about how things at the White House have been going these past two weeks, and it appears the answer is “weirdly.”

Trump and Staff Rethink Tactics After Stumbles

While a lot of political decisions have been implemented in rapid succession off the bat in this presidency, design decisions around the White House seem to get rolled out a little more slowly and thoughtfully. Historically, the president’s design preferences have been known to be over-the-top (at the risk of sacrificing function for aesthetic), so it’s illuminating to see what has been a priority around the new house and what hasn’t:

Visitors to the Oval Office say Mr. Trump is obsessed with the décor — it is both a totem of a victory that validates him as a serious person and an image-burnishing backdrop — so he has told his staff to schedule as many televised events in the room as possible.

To pass the time between meetings, Mr. Trump gives quick tours to visitors, highlighting little tweaks he has made after initially expecting he would have to pay for them himself…

Flanking his desk are portraits of Presidents Thomas Jefferson and Andrew Jackson. He will linger on the opulence of the newly hung golden drapes, which he told a recent visitor were once used by Franklin D. Roosevelt but in fact were patterned for Bill Clinton. For a man who sometimes has trouble concentrating on policy memos, Mr. Trump was delighted to page through a book that offered him 17 window covering options.

Someone get HGTV on the horn.

What It's Like To Lose

On Loss And Losing

Kathryn Schulz will hold your hand

In the micro-drama of loss, in other words, we are nearly always both villain and victim. That goes some way toward explaining why people often say that losing things drives them crazy. At best, our failure to locate something that we ourselves last handled suggests that our memory is shot; at worst, it calls into question the very nature and continuity of selfhood. (If you’ve ever lost something that you deliberately stashed away for safekeeping, you know that the resulting frustration stems not just from a failure of memory but from a failure of inference. As one astute Internet commentator asked, “Why is it so hard to think like myself?”) Part of what makes loss such a surprisingly complicated phenomenon, then, is that it is inextricable from the extremely complicated phenomenon of human cognition.

In this week’s double issue (congrats, you get a break) of The New Yorker, Kathryn Schulz has one of those perfect essays that takes a treacly sounding subject (loss), and turns it upside-down and inside-out, hits every note, and scratches every itch: linguistic, idiomatic, literal, figurative, historical, political, personal, emotional, physical, psychological, pathological, cultural, and, of course, literary. The result is undeniably pretty; the only treacle you will find is from me, for I have decided to describe the good feeling this piece gave me as snug. Read it and it will hold you tight.

In my defense:

snug |snəɡ|

ORIGIN

late 16th century (originally in nautical use in the sense ‘shipshape, compact, prepared for bad weather’): probably of Low German or Dutch origin.

It's My Birthday, I Can Hide If I Want To

And other answers to unsolicited questions.

“My 30th birthday is coming up and some of my friends want to do a big party. I’m not so sure. What should I do?” — Birthday Betty

I don’t know if it’s a New York thing. But who decided adult people have to go out for drinks with their friends on their birthdays every year. I mean every year? The best birthday I ever had was when I was 5. I got a stuffed blue dinosaur with sewn buttons for eyes. I called him “Dino.” It was the Blizzard of ’76. So like 4 feet of snow fell in two days. My young classmates had to be held over large snowbanks and passed to another adult on the other side. It’s one of my first memories and definitely one of my finest.

No birthday could ever live up to that one. And none ever should. When you are young you believe that you’re special and on your birthday everything gets to be about you. When you’re older you realize that birthdays are meaningless and getting older is fine because death will probably be a huge relief.

30th birthdays are kind of traumatic, so I understand why you may have some misgivings about partying. I spend most parties in the corner with Ben, just bored as hell. Drinking a beer. I feel like the oldest person at most parties. I also enjoy spending most of the evening checking out people’s bookshelves. It’s always a terrifying look at someone else’s psyche. These are just the books they want people to know they’ve read. Nietzsche next to Toni Morrison next to The Watchmen. I always wonder where people hide their porn during parties. On their computers, I guess. But that’s the books I want to see on display on bookshelves at parties. Weird fetish coffee table books. Popping balloons. That kind of stuff.

Are you a party person? Or would you rather spend your birthday quietly playing hooky, far from the madding crowd? 30 is rough. 40 is rough. But after that, time means nothing. Except that you’re getting closer to retirement. Which, for me, will be a lot like working. I’ll be shelving books at the bookstore until I keel over, probably. Unless shelving drones are coming.

You can spend your birthday with your friends. But I always personally use it as a day to take my own temperature. Quite literally. I have a doctor’s appointment on my birthday. Then I’ll screw around in the city. Probably go to a movie. Get some tacos. Maybe shop for some books and some New England Patriots Super Bowl Champions stuff. I have a lot of it from over the years. The Patriots winning Super Bowls is the only birthday present I need. Also if I could get a stuffed dinosaur with buttons for eyes, that would be cool. Maybe some Ms. Marvel comic books. No big deal.

Birthdays don’t have to be a day of public consumption. That’s what drinking holidays are for. I get a little cranky on my birthday. If I’m at work I’ll be like “Why are you yelling at me? It’s my birthday!” It turns things awkward with bookstore customers. Your birthday is yours. Do with it as you may. Friends can be nice sometimes, too, I guess. All those other days of the year. For me birthdays are a present I give myself. I take off work and hide in a museum or see a dumb movie. I try to not think about living and dying, being alone or living unloved. Not staring at some bookshelf wondering when it will be OK for me to leave.

Jim Behrle lives in Jersey City, NJ and works at a bookstore. He is trying out for the WFMU Morning Show Thursday and Friday from 6–9 AM on 91.9 FM and on the web at wfmu.org

Preliminary Heartbreak

The Adventures of Liana Finck

Liana Finck’s work appears in The New Yorker and on her Instagram feed. Her book is called A Bintel Brief.

A Winged Victory For The Sullen, "Galerie"

We’re still doing this, huh?

Good morning. The world is a ceaseless parade of horror in which happiness is either improbable rumor or faded memory.

To celebrate their tenth anniversary, London label Erased Tapes is offering a free compilation of recent works which you can stream here or download, if you are one of the seven remaining people who does that sort of thing, here. Below you will find the track from A Winged Victory For The Sullen that features on the compilation and is also part of their soundtrack to Iris. Enjoy.

New York City, February 2, 2017

★★★ One window in a flat facade full of windows caught coral-pink light while everything else was still dim. What came after was not tentative at all, but full brilliant day. A drab tan brick wall, in the corner of a window, out the corner of an eye, was as chromatically rich as a patch of sunset. The gleam in a hat’s furry pompom flexed with each step the wearer took down the subway stairs. There was no need to consult a marmot to feel the sun asserting its advantage over the season and the calendar. Even when the late clouds had gone purple, a trace of whiteness clung to their edges as they slid across the sharp-drawn moon.

In His Own Words

It’s time to use Trumpspeak against him

In just two short weeks, President Donald Trump has destabilized the globe and quickly eroded even our most trusted alliances. This is exactly what his likely sponsor Putin wants, of course. This is exactly what his white supremacist advisor Bannon wants — he’s said so on the record (“Lenin wanted to destroy the state, and that’s my goal, too.”). And if sowing fear in the populace offers the GOP an excuse to pump up military spending, so be it. Most Americans, however, prefer to sleep well at night. And if we’re going to take a clear, resounding stand against this unthinkable menace, we have to use his own tricks against him.

Think about how you might discuss the head-spinningly bad judgment that led to his first and failed military operation in Yemen. Instead of talking about how all special ops are sticky but President Obama, in spite of his flaws, was incredibly careful about not putting American forces in harm’s way, try this:

It was a disaster, a huge disaster, and totally preventable. Trump messed up. Completely incompetent.

Or maybe you’d say:

Those SEALs went in there, and got torn apart. Nightmare, never should’ve happened. Trump messed up, big league. Completely unstable.

And you’d also definitely say:

Impeach the guy. He’s an unstable person. Yemen? Disaster. Everyone knows it’s true. Even he knows it. Awful. Everyone agrees.

Sure, it sounds like an SNL skit. Nonetheless, this is how the resistance (and the Democrats in office and those running for office) must communicate now. With simple, repetitive talking points. Forget clever. Use Trump’s rhetoric. Reckless, scary words are the most useful words to describe him, because almost everything he does is reckless and scary. For example:

And the phone calls, to Mexico, Australia? Unbelievable. He wants to start wars. Impeach the guy. Totally unstable. Everyone agrees.

Another important rule of Trumpspeak? Don’t let anything go. During the election, we kept hearing “crooked” and “emails” and “Benghazi” about Hillary. So keep every single travesty on the tip of your tongue. Repeat, repeat, repeat to the point where you’re boring yourself. When some new horror comes along, add it to the mix, very few words, oversimplified:

Bowling Green Massacre? Total lie. An embarrassment. Kellyanne Conway is an unstable person. Let the mentally ill buy guns? Are you crazy? Terrible! Let Putin bomb Ukraine? Bad idea, very bad. Incredibly dangerous.

Then return to the big ones:

Look at Yemen. Disaster. Totally preventable. More nuclear arms? Is he joking? He’s dangerous. Unsafe. Has to go. It’s horrifying, an embarrassment. Everyone knows it.

If you’re not boring yourself, you’re not doing it right. Seriously.

It’s time to stop trying to sound like the smartest person in the room. Your psychoanalysis of our new president only makes you sound hung up on unimportant brainiac things. Details, issues, policy analysis? Those are great for longer pieces, sure, but they’re too subtle to spread virally on social media, and too complicated to inject into conversations and protests and action calls. Make sounds that any human can understand. Throw in some core values if you want, but make that simple, too:

He’s dead wrong on immigration. Everyone knows it. Doctors, academics, American citizens, treated like criminals? Terrible. An embarrassment. He’s unfit. He‘s gotta go.

Remember that simple messages will make you sound more trustworthy to a lot of people. Thanks, TV culture! Your detailed analysis of high capitalist corruption is not going to help that much. Instead, say this: HE’S TRYING TO START A WAR.

Of course, Democrats and progressives are incredibly afraid of using rhetoric of fear, like Trump and Bannon do. But isn’t fear our new reality? Aren’t we scared out of our minds over Trump, a man who has quickly demonstrated that he’s self-obsessed, unthinkably reckless, and utterly incapable of making even the faintest diplomatic sounds come out of his mouth? We can’t sit back and wait, because his mistakes are going to build on each other until they snowball into a global disaster.

And how would Trump say that?

We’re in big trouble, huge trouble. This guy wants to start World War III. We have to stop him. He’ll get us all killed.

Remember that standing up to Trump is not about creating chaos. Standing up to Trump means restoring safety to our world. This is a rhetorical strategy — linking Trump to danger, linking Trump’s removal to safety — but it’s also plainly true: We don’t have to set stuff on fire to make our point. That would only strengthen Trump, giving him an excuse to send in the militarized police while undermining human rights. Remember what we’re fighting for: Safety. Peace. Human rights. Preventing the US from becoming the laughing stock of the world, or worse, starting global conflicts with nuclear weapons in play.

So repeat the same simple messages. Then call your reps and say the same things. “We’re worried for our lives. We’re worried about our children. Trump is unstable. He’s dangerous.” Ask them: ‘Why aren’t you standing up to him? Why aren’t you protecting us?”

Remember the things Trump said about Hillary? The devil. An unstable person. Belongs in prison. Has tremendous hatred in her heart. Crooked. It’s clear now that every last one of his descriptions of her were, in fact, projections. And now Trump is saying, of his #1 enemy, Lindsey Graham, “He’s trying to start World War III.” You think he’s not projecting this one time?

Millions of people feel the same way about Trump. Millions of people are losing sleep over this man. Stop reading the horrifying news for hours, stop trying to be clever on Twitter, stop impressing your friends with your nuanced analysis of filibustering, and let’s all speak in one, clear, simple voice. Impeachment is political. Trump has committed impeachable offenses, and the list is growing, to the point where impeachment feels inevitable to many observers. A recent poll has four out of ten registered voters supporting impeachment, and that support will only grow as Trump and his advisors continue to behave recklessly. Republicans who stand by him are likely to find themselves on a sinking ship. So pick up the phone and use Trumpspeak:

Trump is incredibly dangerous. Incredibly dangerous! It’s obvious. He’s corrupt, he’s unstable, he’s reckless. Yemen? Disaster. Putin? Pulling the strings. We’re not safe with him in office. Totally unsafe. We need your help. When are you going to take a stand against this guy? When? He’s got to go. It’s obvious. Everyone agrees.

Haruki Murakami's Metaphysics Of Food

How meals and cooking are his most deeply intimate subjects.

The homes that sandwich the passage are of two distinct types and blend together as well as liquids of two different specific gravities. First there are the houses dating from way back, with big backyards; then there are the comparatively newer ones. None of the new houses has any yard to speak of; some don’t have a single speck of of yard space. Scarcely enough room between the eaves and the passage to hang out over two lines of laundry. In some places, clothes actually hang out over the passage, forcing me to inch past rows of still-dripping towels and shirts. I’m so close I can hear television playing and toilets flushing inside. I even smell curry cooking in one kitchen.

—The Wind-Up Bird & Tuesday’s Women from The Elephant Vanishes

Food writing gets a bad rap for being fluffy and bougie, which isn’t quite fair since food is such an essential part of our existence. Outside of the establishment of bona fide culinary writers, many fiction writers have touched on the sensory and emotional aspects of food, from Marcel Proust to Nora Ephron, but no one has tapped into its prosaic humanity quite like the Japanese novelist Haruki Murakami. This is not lost on Murakami fans, and there are a few blogs devoted to the food his characters prepare, like What I Talk About When I Talk About Cooking. Murakami writes intricate plots with an extremely high level of emotional intelligence, but no matter how fantastical his stories are, his characters remain relatable, and food provides the balance between surrealism and normalcy. He weaves food into his stories in a mundane way that communicates the deep-seated reasons of why, how, and what we eat.

The amount of space given over to food in Murakami’s novels is unusual. In Dance Dance Dance, not a day goes by in the narrator’s life that he doesn’t tell the reader what he ate. Food has nothing to do with the plot, though: the book is about a guy searching for a prostitute he once loved. Murakami details the unnamed character’s diet with remarkable banality. In one scene, he’s staying at a luxury hotel and announces he’s tired of the breakfast spread, so he goes to Dunkin’ Donuts and gets two plain muffins. (“You get tired of hotel breakfasts in a day. Dunkin’ Donuts is just the ticket. It’s cheap and you get refills on the coffee.”) This guy is living in 1980s Japan, but this detail makes him immediately more familiar and accessible.

After Dark is a short novel that starts in a Denny’s at precisely 11:56 P.M. Within the first few pages we meet Takahashi, a trombonist-slash-student who’s come to Denny’s for a late-night snack of chicken salad and crispy toast. He proceeds into a short monologue about Denny’s chicken salad, explaining that even though it’s all he orders there, he still looks at the menu. “Wouldn’t it be too sad to walk into Denny’s and order chicken salad without looking at the menu? It’s like telling the world, ‘I come to Denny’s all the time because I love the chicken salad.’” Takahashi’s self-consciousness about his love of the chicken salad (which another character is quick to note is probably full of “weird drugs”) is relatable.

For Murakami, how we eat is a reflection of ourselves. In 1Q84, The Dowager is a wealthy septuagenarian widow who eats natural ingredients and French-influenced lunches like “boiled white asparagus, salad Niçoise, and a crabmeat omelet.” She eats small portions and drinks her tea, “like a fairy deep in the forest sipping a life-giving morning dew.” You get the sense from her diet and table manners not only that she’s well-bred and refined, but almost enlightened. Compare her to Ushikawa, a sleazy lawyer-turned-private-investigator whose family left him and who has no life outside of stalking people under the guise of work. He’s a self-loathing scumbag and he eats like one, too. Where the Dowager eats fresh vegetables, Ushikawa eats processed food like canned peaches and sweet jam buns, and goes days without having a hot meal. The Dowager treats her body like a temple, Ushikawa treats his like a garbage disposal. She is at peace with herself, he is not.

Yuki, a 13-year-old girl in Dance Dance Dance, has a similar diet to Ushikawa. Though she is of a vastly different demographic, her propensity to eat crap stems from the same feelings of being underloved. Her parents are wealthy and famous, but they’re estranged from each other and neglectful of her. She’s doesn’t have any friends until she meets the narrator, twenty years her senior, who becomes her platonic companion-slash-babysitter. In one scene, he calls and asks if she’s been eating healthy. “Let’s see. First there was Kentucky Fried Chicken, then McDonald’s, then Dairy Queen,” she says. When they hang out, he steers her away from junk food. Later, he takes her to a restaurant where they have roast beef sandwiches on whole wheat bread. He says, “I made her drink a glass of wholesome milk too. The meat was tender and alive with horseradish. Very satisfying. This was a meal.” The narrator takes on the role of nurturer that Yuki’s parents have cast aside, and nourishes her literally and figuratively.

Murakami often shows his characters preparing meals to convey their independence. In Dance Dance Dance, Yuki’s mother’s boyfriend is a one-armed poet who cuts ham sandwiches so perfectly that the narrator wonders aloud how he slices bread with one hand. In Norwegian Wood, Toru watches Midori in awe as she theatrically prepares lunch one afternoon (“Over here she tasted a boiled dish, and the next second she was at the cutting board, rat-tat-tatting, then she took something out of the fridge and piled it in a bowl, and before I knew it she had washed a pot she had finished using”). Midori had taught herself how to cook in the fifth grade because her mother didn’t take care of household things. When we meet her, she’s essentially an orphan: her mother is dead, her father is dying, and her older sister is engaged. Despite her abandonment, she takes care of herself well.

Cooking meals is more than a signal of independence though, it’s an introspective behavior that provides order to the chaos of the outside world. In 1Q84, the two main characters, Tengo and Aomame, unknowingly enter a dystopian universe where they have no control over their lives. At one point, Tengo is being watched by the aforementioned sketchball Ushikawa and he’s wrapped up in accusations of fraud for ghostwriting a best-selling book. The routine of coming home every day and cooking allows him to step away and make sense of what’s going on around him. He often makes elaborate meals out of whatever’s in his refrigerator. Murakami has said that improvisation is his favorite kind of cooking. In one scene, Tengo makes “rice pilaf using ham and mushrooms and brown rice, and miso soup with tofu and wakame.” Cooking is not a chore for Tengo; he “use[s] it as a time to think “about everyday problems, about math problems, about his writing… he could think in a more orderly fashion while standing in the kitchen and moving his hands than while doing nothing.”

You don’t need to go to therapy to know that food can provide comfort, but for Murakami, comfort is also found in the mindfulness that comes from preparing it. In The Wind-Up Bird Chronicle, Toru is newly unemployed and spending most of his time cooking and looking for his lost cat. At the beginning of the book, the phone rings while he’s making spaghetti (chapter 1) and a tomato-and-cheese sandwich (chapter 3), and he tries to resist answering it until he finishes preparing his food. “I let the phone ring three times and cut the sandwich in half. Then I transferred it to a plate, wiped the knife, and put that in the cutlery drawer, before pouring myself a cup of coffee I had warmed up. Still the phone went on ringing.” Toru is mindful of each unremarkable step in the sequence; by letting the phone ring, he’s trying to block the outside world from intruding on his routine.

As any casual binge-eater can attest, we sometimes eat to fill a void. In the short story “The Second Bakery Attack,” a newlywed couple wakes up in the middle of the night unbearably hungry. They’ve only been married two weeks and aren’t completely at ease with each other (“we had yet to establish a precise conjugal understanding with regard to the rules of dietary behavior. Let alone anything else.”) Long story short, after unsuccessfully scrounging for food in their kitchen, they drive to McDonald’s to rob it, but instead of demanding money, they demand 30 Big Macs. He eats six, she eats four, and as soon as their hunger vanishes, they feel closer to each other.

In Kafka on the Shore, when Kafka runs away from home, he stays at a hotel and eats a big breakfast of toast, hot milk, ham and eggs. It’s a warm, nutritious meal that should fill him up, but he’s not full. As he looks around hopelessly for seconds, the voice in his head (“the boy named Crow”) interjects, “You’re not back home anymore, where you can stuff yourself with whatever you like…you’ve run away from home, right? Get that through your head. You’re used to getting up early and eating a huge breakfast, but those days are long gone, my friend.” He’s just left a cushy but lonely life at his father’s home with the vague intention to “journey to a far-off town and live in a corner of a small library.” He’s chosen a place at random (“Shikoku, I decide. That’s where I’ll go. There’s no particular reason it has to be Shikoku, only that studying the map I got the feeling that’s where I should head.”) He has yet to reach his destination or realize the subconscious reason behind wanting to leave home, but his insatiable hunger is indicative of his itinerancy; it’s like he can’t feel full unless he’s secure.

There is a telling passage in Kafka on the Shore about the myth from Plato’s Symposium, that each person was made out of two people, and then God cut everybody in two so they’d spend their lives trying locate their missing half. This idea — and the corresponding one that humans are inherently lonely — is palpable in many Murakami stories, especially when his characters are eating. Midori and Toru’s courtship in Norwegian Wood takes place over meals. They meet for the first time at a quiet diner near their university: Toru is eating alone (a mushroom omelet and green pea salad) and Midori, who recognizes him from class, leaves her friends and goes over to introduce herself. She asks if she’s interrupting him and he responds point-blank, “No, there’s nothing to interrupt.” The reader realizes that Toru has feelings for Midori when she doesn’t show up to school and he ends up having “a cold, tasteless lunch alone.”

While one relationship is built over sharing meals in Norwegian Wood, another comes undone in The Wind-Up Bird Chronicle. Toru takes care of household duties like grocery shopping and dinner while his wife, Kumiko, is at work. She usually is home at 6:30 p.m., but one night she doesn’t return until 9. Toru starts preparing a stir fry of beef, onions, green peppers, and bean sprouts when she comes home, but as he’s cooking it, she starts a fight with him because he doesn’t know that she “absolutely detest[s] beef stir fried with green peppers.” It’s exactly the kind of irrational fight you start when you’re annoyed at someone and need something to pick at, and it foreshadows their future as a couple. A few chapters later, she doesn’t come home at all, and Toru aimlessly putters around the kitchen and eats breakfast alone. This is more heart-wrenching than it seems: they’ve never once missed breakfast together since they’ve been married — it’s the beginning of the end.

In an “Art of Fiction” interview in the Paris Review, Murakami says his job as a fiction writer is “to observe people and the world, and not to judge them.” He describes with incessant detail his characters eating and preparing food, and their behaviors immediately become familiar to us when we view them through this lens. We’ve all experienced Yuki’s cravings for junk food when we feel empty inside, Tengo’s mesmerizing waves of calmness as we cook dinner at home after a stressful day, and both Torus’ sense of loneliness and yearning when we eat a meal alone that we’d rather be eating with someone we care about.

Murakami uses food to convey universal feelings of comfort, love, partnership, and independence. As Toru observes while eating a cucumber in Norwegian Wood, “It’s good when food tastes good. It makes you feel alive.” That he makes this observation in regards to a zero-calorie vegetable that tastes mostly of water suggests that you can find satisfaction in even the simplest of things. You can eat the cucumber without tasting it, or you can live, and appreciate a refreshing taste hidden beneath bitter skin. We don’t eat to merely survive, we eat to experience life.

Every Article The New York Times Published About HBO's 'Girls'

During its six-season run from 2012–2017.

March 2, 2012:

Lena Dunham on ‘Girls,’ Her New HBO Comedy

March 31, 2012:

April 12, 2012:

Lena Dunham’s ‘Girls’ Begins on HBO

April 23, 2012:

How HBO’s ‘Girls’ Mirrors the Spirit of Sisterhood in Nature

June 22, 2012:

‘Girls’ Fans Interact With the Show’s Setting

September 14, 2012:

Allison Williams Is Standing Out From the New Girls at Fashion Week

January 2, 2013:

On This Hit Show, the Clothes Make the ‘Girls’

January 2, 2013:

Zosia Mamet Is Still Getting Used to Being Your New Best Friend

January 4, 2013:

January 10, 2013:

Lena Dunham’s ‘Girls’ Returns to HBO

March 14, 2013:

Asked & Answered | Allison Williams

March 18, 2013:

Lena Dunham Gives ‘Girls’ Season a Romantic Finale on HBO

January 8, 2014:

Lena Dunham Attends the HBO ‘Girls’ Season Premiere in Manhattan

January 9, 2014:

‘Girls’ Returns and ‘Looking’ Will Debut on HBO

January 12, 2014:

‘Girls’ Returns, and a New Day Begins

January 17, 2014:

Allison Williams and Cynthia Nixon Talk About ‘Girls’ and ‘Sex and the City’

March 18, 2014:

Jemima Kirke’s Paintings of Girls

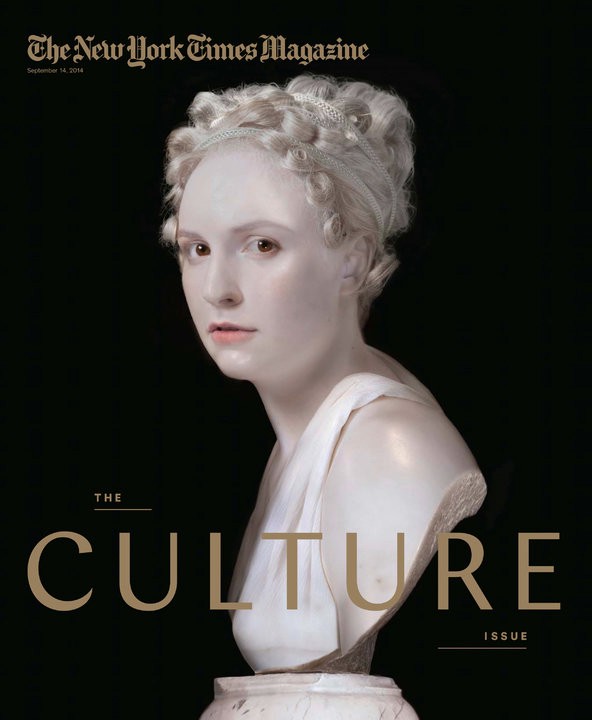

September 10, 2014:

September 10, 2014:

Lena Dunham Is Not Done Confessing

September 10, 2014:

The Making of Lena Dunham’s Bust

September 10, 2014:

Under Cover: On Turning Lena Dunham Into a Neoclassical Bust

October 4, 2014

January 6, 2015:

March 24, 2015:

Jemima Kirke’s Workout Thwarts the Usual Fitness Trends

January 6, 2016:

‘Girls’ Will Say Goodbye After Sixth Season

February 17, 2016:

‘Girls’? Aren’t They Women Yet?

February 19, 2016:

‘Girls,’ on HBO: Getting It Together in Penultimate Season

April 6, 2016:

On HBO’s ‘Girls,’ a Kitty Genovese Plot Proves Eerily Timed

April 17, 2016:

‘Girls’ Finale: Is It Just Us, or Did the Show Get Better?

April 18, 2016:

You Don’t Like the Girls in ‘Girls’? That’s Its Genius.

February 1, 2017:

February 2, 2017:

6 Ways ‘Girls’ Changed Television. Or Didn’t.

February 9, 2017

The Women of ‘Girls’ and Protest Whack-a-Mole

February 11, 2017

Lena Dunham and Judd Apatow on ‘Girls,’ ‘Geeks’ and Trolls

February 24, 2017

Lena Dunham and Matthew Rhys on the Latest ‘Girls’ Provocation

April 16, 2017

Review: ‘Girls’ Finale Walks Into the Future, Pantless and Unbowed

April 16, 2017

Lena Dunham on the ‘Girls’ Finale and That Last Shot of Hannah

April 19, 2017

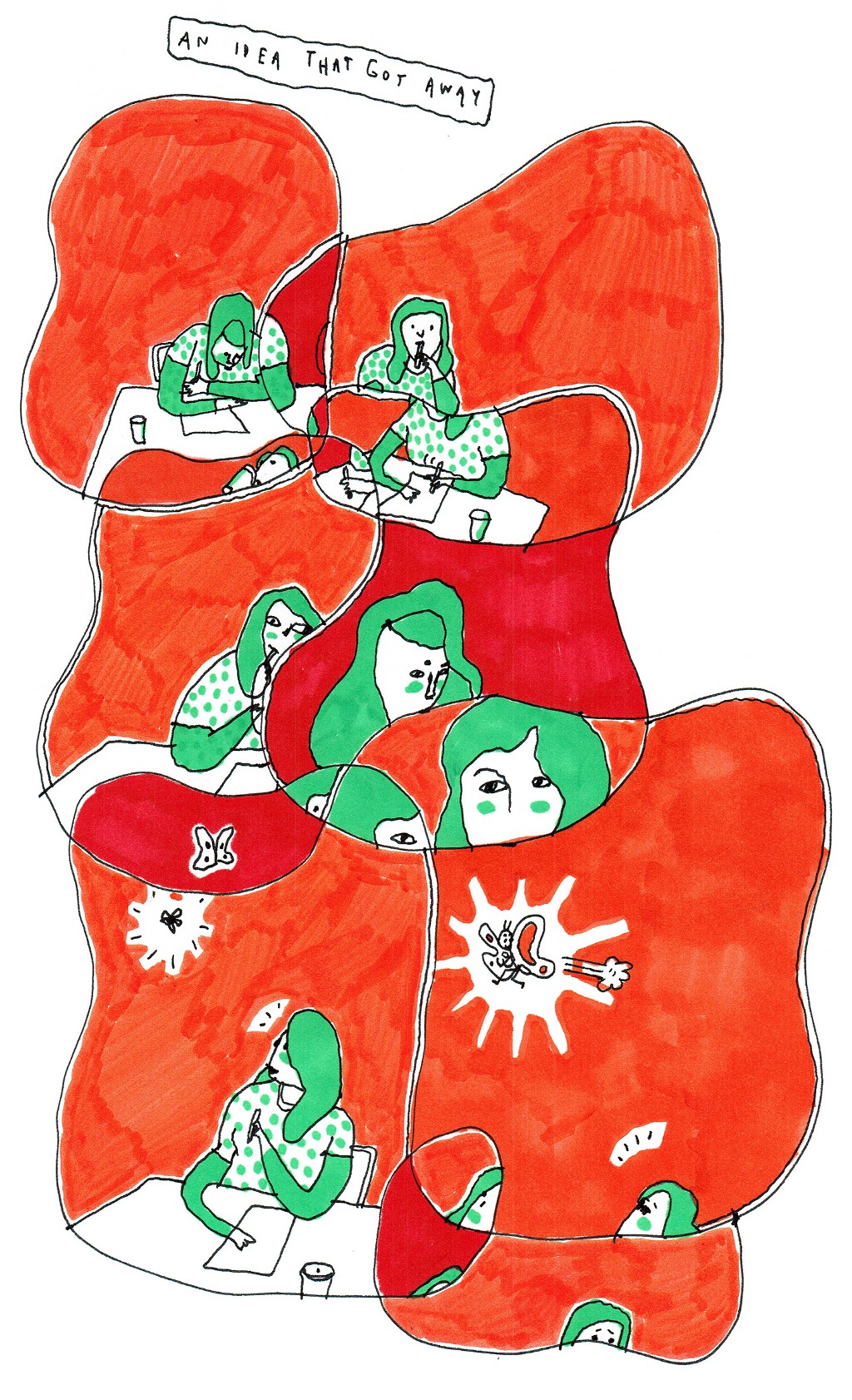

The Idea That Got Away

The Adventures of Liana Finck

Liana Finck is a comics artist AND cartoonist, unbelievable as it sounds. Her work appears on Instagram. (she puts it there).